Abstract

Background: Pulmonary valve infective endocarditis (PVIE) is a rare form of infective endocarditis (IE) and is associated with high mortality and severe complications. Guidelines for treatment of this form of IE are scarce and based on general recommendations. We report a case series of PVE. Detailed Case Description: Case 1—A 36-year-old female with congenital pulmonary artery stenosis, dyspnea and leg edema symptoms for 2 months. Blood cultures yielded Staphylococcus spp. and Corynebacterium sp., and echocardiography revealed multiple floating vegetation at the pulmonic valve and surrounding structures. The clinical course was complicated with sepsis and multi-organ failure. Urgent surgery with pulmonary homograft implantation resulted in successful five-year outcome. Case 2—In a 38-year-old male with previous tetralogy of Fallot correction and symptoms of fatigue, fever, myalgia, and photophobia, echocardiography was suggestive of PVIE. The clinical course was complicated with septic shock, multi-organ failure, ischemic stroke with hemorrhagic transformation and death on the 12th day of hospitalization. Case 3—A 41-year-old male without previous medical history was hospitalized due to prolonged fatigue, fever, dyspnea, and leg edema. He was diagnosed with multi-valve infective endocarditis, affecting the aortic, tricuspid, and pulmonary valve. Acute heart failure and hemodynamic instability indicated urgent surgery with aortic valve replacement and reconstruction of the tricuspid and pulmonary valves. At four-year follow up he was doing well. Conclusion: Symptoms in PVIE may be versatile, and diagnosis is often delayed. High level of suspicion, early recognition, and echocardiography are cornerstones in diagnostics. Despite the standpoint that medical therapy is first-line, the role of surgery needs to be advocated in particular cases.

1. Introduction

Infective endocarditis is rare but still associated with high morbidity and mortality. Right-sided IE (RSIE) accounts for 10% of all infective endocarditis (IE) cases [1], with pulmonary valve endocarditis (PVIE) being extremely rare and representing only 1–2% of all IE cases [2]. Some surgical series report 0.5% PVIE involvement incidence within 1362 operated IE patients [3]. Lower pressure gradients at the valves, combined with reduced blood oxygen within the right-heart chambers, might contribute to the development of RSIE [4]. Nowadays PVIE is most often seen in patients who have undergone surgical or percutaneous pulmonary valve (PV) procedures [5,6,7,8,9].

Initial PVIE treatment, as well as other RSIE treatments, are based on intravenous antibiotics; however, surgical intervention may be warranted in several situations, such as uncontrolled infection, huge embolic potential, and hemodynamic deterioration [10].

We report three cases of PV endocarditis. The aim of this case series is to describe underlying risk factors, symptoms, clinical and diagnostic challenges, microbiological features, and management of PVIE. These patients were part of the ESC-EORP Euro-ENDO registry where our high-volume center, among 156 others from 40 countries, recruited 42 (1.4%) patients [11].

2. Detailed Case Series Description

2.1. Case Report No 1

A 36-year-old female was hospitalized for symptoms of dyspnea and leg edema that started 2 months before. She suffered from adult congenital heart disease (ACHD)—pulmonary artery stenosis. According to data from the community care hospital, urine culture was positive for Staphylococcus. In-hospital trans-thoracic echocardiography (TTE) revealed multiple vegetations on the stenotic pulmonic valve. Repeated blood cultures were positive for Staphylococcus spp. and Corynebacterium sp. An antibiotic treatment with Vancomycin and Ciprofloxacin was introduced. Physical examination revealed leg edema and diffuse petechiae on the skin of the abdomen and legs, as well as the mouth mucosa (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Skin hemorrhage at the lower extremities and in mouth mucosa—Case 1.

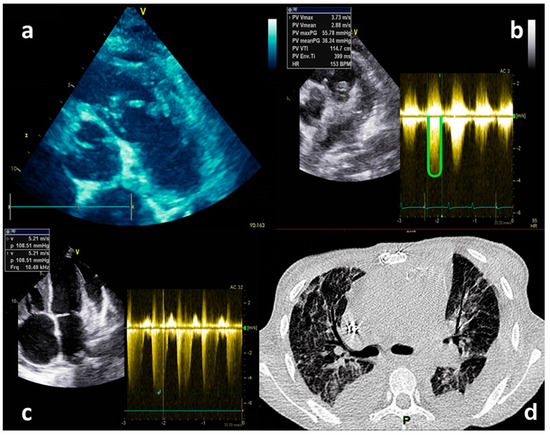

Heart auscultation revealed predominantly systolic as well as diastolic murmur over the pulmonic valve, and lung auscultation was suggestive of pleural effusion due to absent breath sounds in basal and mid-lung portions. The laboratory findings show a leucocyte count of 10.72 [ref. 4–10] × 109 hemoglobin of 79 [ref. 120–170] g/L, C-reactive protein (CRP) was 50 [ref. 0–5] mg/L, procalcitonin 0.96 [ref. 0.0–0.05] ng/mL, and creatinine [ref. 50–120], e GFR 40 mL/min/1.73 m2. A chest X-ray was suggestive of pleural effusion, showing homogenous opacity and obliteration of the costophrenic angles bilaterally. Diagnostic thoracocentesis with cytochemical analysis confirmed that the fluid was exudate. TTE revealed multiple floating vegetations (up to 2 cm) (Figure 2a) at the right ventricular outflow tract, pulmonary valve, and the walls of the pulmonary artery (Video S1: Vegetations on PV and RVOT), with significant pulmonary valve stenosis with a transpulmonary valve gradient of 55 mmHg (Figure 2b), and moderate pulmonary valve regurgitation. The ejection fraction (EF) of the left ventricle was preserved. The right heart chamber’s diameters were normal, tricuspid regurgitation was estimated as moderate and right ventricle systolic pressure was severely increased by 108 mmHg (Figure 2c). A Thoracic CT scan showed multiple septic embolizations in the lung parenchyma, lung atelectasis, pleural effusion, and multiple floating vegetations in the pulmonary artery (Figure 2d). Despite the optimization of antibiotic therapy (2 weeks of Vancomycin and Gentamycin with concomitant treatment), she remained with laboratory and clinical signs of sepsis, with persistently worsening renal failure. Repeated TTE was without changes in distribution and size of previously seen vegetations, but with signs of both left (drop in EF to 30%) and right ventricular failure. Our hospital’s endocarditis team (ET) decided to perform the surgery with homograft implantation. Since there were no homografts in our country, after the international ET evaluation, she underwent cardiac surgery in the neighboring country of Croatia. Her EuroSCOREII was 10.68%. On the pulmonary position, a homograft was placed, and a resection of stenotic and infected infundibulum was performed (Figure 3). The postoperative course went well. Postoperative TTE showed normal trans-pulmonic valvular gradients without regurgitation, left ventricular improvement from LVEF 35% to 50%, moderate tricuspid regurgitation, and one floating filamentous formation connected to the septal cusp of the tricuspid valve. After surgery, she has referred again to our hospital. Transesophageal echocardiography (TOE) revealed that the filamentous formation was a thrombotic mass. The treatment was continued with parenteral antibiotics and anticoagulant therapy. After 54 days postsurgery, TTE verified that the thrombus was dissolved. She was discharged in good condition on the 57th postoperative day. Five years later, she remains well, with no symptoms, and handling physical strains without problems.

Figure 2.

Echocardiography TTE and CT imaging−Case 1. (a) TTE−Multiple floating vegetations in the right ventricular outflow tract, pulmonary valve, and on the wall of the pulmonary artery. (b) TTE−Gradient across pulmonary valve. (c) TTE−Maximal velocity of the tricuspid regurgitation. (d) MSCT−Multiple septic embolizations in the lung parenchyma, lung atelectasis, pleural effusion.

Figure 3.

Intraoperative finding—Case 1. By courtesy of Prof. Darko Anic MD PhD.

2.2. Case Report No 2

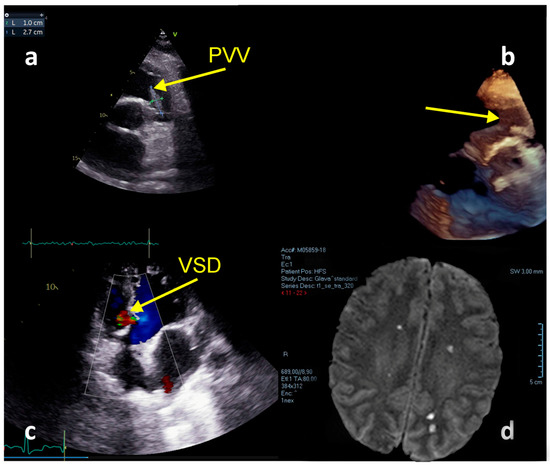

A male aged 38 years was referred to our hospital from the clinic for infectious diseases, with a diagnosis of severe sepsis. He experienced 5 days of symptoms of increased temperature up to 40 °C, fatigue, myalgia, and photophobia. An initial brain CT scan and ultrasonography of the abdomen revealed no significant changes. Antibiotic treatment was initiated with levofloxacin. After TTE suggestive of PVIE the patient was transferred to our hospital. His medical history included tetralogy of Fallot surgical repair at the ages of 1 and 7. At admission to our hospital, he had symptoms and signs of heart failure (HF) and multiple organ failure (MOF). A whole systolic murmur (4/6) was heard at the precordium. Laboratory tests at admission found a leucocyte count of 20.33 [ref. 4–10] × 109, hemoglobin 117 [ref. 120–170] g/L, PLT 39 [ref. 150–400] × 109, CRP 155 [ref. 0.0–0.05] mg/L, creatinine 416 [ref. 50–120] μmol/L; eGFR 15 mL/min/1.73 m2, NT-proBNP: >25,000 [ref. 0.0–125.0] pg/mL, procalcitonin: 50.68 [ref. 0.0–0.05] ng/mL, hs-Troponin: 151.4 [ref. 0.0–25.0] ng/L; D-Dimer: 5018.88 [ref. 0.0–500.0] ng/mL. TTE revealed massive PV vegetation (Video S2: Pulmonary valve vegetation) (dimension 2.4 × 0.7 cm), residual ventricular septal defect (VSD) in the membranous part of the interventricular septum, impaired left ventricular systolic function with EF of 25–30%, right ventricular enlargement with decreased systolic function (TAPSE = 1.5 cm; FAC = 43%; S’ = 0.08 m/s), and pulmonary hypertension of 43 mmHg (Figure 4a–c). He was treated with therapy attributed to heart and renal failure: diuretics, dobutamine, noradrenaline, and continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration (CVVHDF). During the hospitalization, several antibiotics were used (metronidazole, linezolid, ceftriaxone) and no positive blood cultures were found. On the first day after the admission, the hospital ET indicated PV homograft surgery. On the second hospital day, the patient experienced deep neurological deterioration. Magnetic resonance of the brain (Figure 4d) showed multiple septic embolizations. His EurSCOREII was 83.23%. Unfortunately, the lack of PV homograft and neurological complications led to postponing the cardiac surgery procedure and resulted in a lethal outcome on the 12th day of hospitalization, due to a hemorrhagic transformation of ischemic stroke.

Figure 4.

Echocardiography and MRI imaging—Case 2. (a) Floating vegetation in the RVOT. (b) TTE + 3D reconstruction. (c) Residual VSD; (d) MRI—Multiple septic brain embolization.

2.3. Case Report No 3

A 41-year-old male was referred to our tertiary care hospital with confirmed IE of the aortic, tricuspid, and pulmonary valves, along with severe HF. He was previously hospitalized in secondary care hospital due to prolonged fatigue, fever, dyspnea, and leg edema. Initial treatment with antibiotics and supportive therapy did not yield any improvement. Laboratory findings at the admission to our hospital revealed a leucocyte count of 5.8 [ref. 4–10] × 109, hemoglobin 93 [ref.120–170] g/L, PLT 218 [ref.150–400] × 109, CRP 57.2 [ref.0–5] mg/L, creatinine 226 [ref.50–120] μmol/L; eGFR 31 mL/min/1.73 m2, NT-proBNP: >25,000 [ref.0–125] pg/mL, prokalcitonin: 0.15 [ref.0–0.05] ng/mL, hs-Troponin: 151.4 [ref.0–25] ng/L; D-Dimer: 5018.88 [ref.0–500] ng/mL. The blood culture samples yielded Staphylococcus and Klebsiella pneumonia, and treatment with susceptible antibiotics vancomycin and gentamicin was introduced.

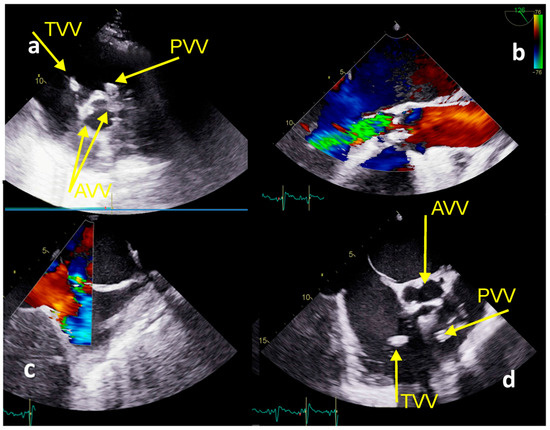

TTE and TOE confirmed floating vegetations at the tricuspid valve (1.4 cm × 1.3 cm) with severe regurgitation and right ventricular systolic pressure of 85 mmHg, PV with floating vegetation (1.5 cm × 1.0 cm) (Figure 5a,d), the destruction of the aortic valve with severe aortic regurgitation (Figure 5b), and patent foramen ovale with L-R shunt (Figure 5c), with left ventricular EF of 53%. Severe hemodynamic deterioration with pulmonary edema advocated emergency ET to indicate urgent surgery. His EuroSCOREII was 52.38%. Urgent coronagraphy showed a normal angiogram. Cardiac surgery included aortic valve replacement (mechanical aortic valve ATS No.24 ATS Medical, Inc, Minneapolis, MN, USA), mitral valve annuloplasty (SJM™ Rigid Saddle Ring No 28) (St. Jude Medical, Inc., St. Paul, MN, USA), an excision of tricuspid valve vegetation, triangular resection of the septal leaflet, direct reconstruction with polypropylene 5-0 stitch and De Vega annuloplasty tricuspid annulus reconstruction. Additionally, the excision of vegetation positioned within the posteromedial and posterolateral pulmonary valve leaflet with pulmonary valve plastics and stitches on the pulmonary valve commissures were performed. After 43 days the patient was discharged and was doing well at 4-year follow-up.

Figure 5.

Echocardiography TTE and TEE imaging−Case 3. (a) TTE: TVV−vegetation at the tricuspid valve, PVV−vegetation at the pulmonary valve, AVV−vegetations at the aortic valve; (b) TOE−severe aortic regurgitation; (c) TOE−patent foramen ovale; (d) TOE−vegetations at the tricuspid, pulmonary, and aortic valves.

The patients’ findings compared to other PVIE cases are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative findings among PVIE cases.

3. Discussion

Our case series demonstrates that PVIE is usually seen in younger patients. Two of the three had a history of congenital heart disease. The third case was without previous medical history but with IE of three valves. These findings are in line with previous reports that PVIE is usually seen in previous CHD and that structurally normal pulmonary valve is hardly affected alone [11]. Our case series demonstrates that often, signs and symptoms of PVIE can be versatile, and the diagnosis is often delayed. Guidelines recommend that IE should be considered in any patients with CHD presenting with ongoing fever and signs of systemic infection [10]. All cases were associated with serious complications, and one had an unfavorable outcome. Despite improvements in diagnosis and treatment, infective endocarditis is associated with high mortality and severe complications, and remains a therapeutic challenge [12].

Echocardiography is the cornerstone of the diagnostic algorithm in IE. Although echocardiography in PVIE could be challenging for TTE and TOE, both provide fundamental and reliable morphological and functional information for diagnosis [6]. In all three PVIE cases, TTE and TOE were key in confirming the diagnosis. Repeated echocardiography in our cases was useful in complications, clinical follow-up and surgery planning timing.

The microbiology of IE from Streptococci has been shifted to Staphylococci, these being the most commonly encountered microorganism [13]. Two of our patients’ positive blood cultures yielded a Staphylococci species. Corynebacteria usually have low virulence and cause catheter-related bloodstream infections and native- and prosthetic-valve endocarditis [14]. Corynebacteria were found in our Case No 1 despite no catheter-related involvement, complicating Staphylococcus infection. Klebsiella pneumonia most often causes life-threatening community- or hospital-acquired pneumonia, but is a rare cause of IE [15,16]. In our Case No 3, Klebsiella pneumoniae infection was associated with prolonged antibiotic treatment in secondary care hospital. Culture-negative IE has been connected with increased short-term and long-term mortality, particularly in receiving medical treatment only, similar to in our second case [17].

Although RSIE and PVIE are usually treated conservatively and considered to have a benign course with good clinical outcomes, our case series demonstrates that the clinical course might be very complicated, with an uncertain outcome. In hemodynamic deterioration, embolic events or uncontrolled infection treatment courses should be reconsidered and directed toward cardiac surgery. In the case of our two patients with favorable outcomes, the complicated PVIE course was resolved with urgent cardiac surgery. The presence of ventricular septal defects can lead to the multivalvular distribution of endocarditis [18]. In Case No 2, despite no visible involvement of left-sided structures, the patient experienced systemic embolization, probably due to the right shunt through VSD. The use of TOE is essential in the visualization of structures and intracardiac defects when evaluating a patient with suspected or known endocarditis [19].

The current guidelines define the criteria for surgical intervention for RSIE [10], but those recommendations are mainly based on tricuspid valve involvement studies. Decisions on urgent surgery in critically ill patients with MOF may be debatable [20]. PVIE is very rare; Chowdhury et al. [21] anticipated that 70 cases of isolated PVIE were reported between 1979 and 2013, and among these such devastation of the pulmonary valve and neighboring structures like in the cases we reported are rarely seen.

Expert opinion is that the majority of PVIE could be managed conservatively with lower mortality compared to left-sided infective endocarditis [10,22]; however, as this is a rare form of IE, the evidence for these recommendations is limited. Early reports found that 40% of patients with isolated PVIE eventually required surgery, and the overall mortality was 24% [5], with excellent outcomes in those who underwent surgery. Isaza et el. [23] reported 24 PVIE cases over a 16-year period, and found that 54.2% were with prosthetic valves and 75% required surgery; in hospital, mortality was 8.8% with an overall 2.8-year median follow-up mortality of 41.7%. The authors demonstrated that surgery plays an important role in the management of PVIE, particularly for those with prosthetic PVIE. In addition, the authors reported [24] 12 patients with PVIE; 4 underwent surgery, and 7 were treated conservatively, while mortality was 42.8% in the conservative vs. 25% in the surgery treatment group. In a case series of eight patients [25], five of the six treated conservatively died, and two were operated on with successful outcomes. Also, four cases of PVIE without underlying heart diseases who required surgical interventions [26] exhibited good outcomes. Zhang et al. [27] showed an efficaciously operated case of PVIE, and other authors have documented successfully treating PVIE using pulmonary valve replacement [28,29]. Agrawal et al. [30] reported the successful replacement of the pulmonary valve with a bioprosthetic valve and patch closure of the ASD in patient with PVIE. In an opposite case report, autopsy showed a congenital bicuspid pulmonary valve, affected by infective endocarditis [31], and even after this, a case of cardiac surgery-complicated [32] multi-organ failure concluded with mortality. Dhakam et al. [33] reported a case of PVIE treated conservatively with lethal outcome after prolonged hospital stay.

We encountered several problems in patients with PVIE: the vegetations were multiple and widely spread; thromboembolic complications were present, as well as the MOF; the infective agent was uncommon. In these circumstances, medical therapy is insufficient, and the first-line therapy and approach should be shifted to surgical treatment. Surgical correction with homograft and PV correction could offer a good long-term result. Moreover, to successfully manage PVIE, it is necessary to anticipate possibilities for adverse outcomes [34] using all the therapeutic possibilities in nearby regions with the help of a coordinated ET approach.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, our case series demonstrate that often, the signs and symptoms of this rare form of pulmonary valve endocarditis can be unspecific, versatile, and the diagnosis is often delayed. A high level of suspicion and early echocardiography, especially in patients with congenital heart disease, might be crucial in optimal management. Our experience suggests that an individual approach and cardiac surgery could ensure successful long-term outcome.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/medicina59071213/s1, Video S1: Vegetations on PV and RVOT; Video S2: Pulmonary valve vegetation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.S.; validation, A.M. and S.B.; formal analysis, M.S.; investigation, M.T.; resources, T.P.; writing—original draft preparation, I.S.; writing—review and editing, A.M. and T.M.; supervision, L.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Cardiovascular Diseases of Vojvodina (protocol code 3113/1-8 approved on 8 September 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Acknowledgments

Darko Anić, Bojan Biočina, University Hospital Centre Zagreb, University of Zagreb School of Medicine.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shmueli, H.; Thomas, F.; Flint, N.; Setia, G.; Janjic, A.; Siegel, R.J. Right-Sided Infective Endocarditis 2020: Challenges and Updates in Diagnosis and Treatment. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e017293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruun, N.E.; Habib, G.; Thuny, F.; Sogaard, P. Cardiac imaging in infectious endocarditis. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.T.; Shrestha, N.K.; Witten, J.; Gordon, S.M.; Houghtaling, P.L.; Tingleff, J.; Navia, J.L.; Blackstone, E.H.; Pettersson, G.B. Rarity of invasiveness in right-sided infective endocarditis. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2018, 155, 54–61.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goud, A.; Abdelqader, A.; Dahagam, C.; Padmanabhan, S. Isolated pulmonic valve endocarditis presenting as neck pain. J. Community Hosp. Intern. Med. Perspect. 2015, 5, 29647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassling, R.S.; Rogler, W.C.; McManus, B.M. Isolated pulmonic valve infective endocarditis: A diagnostically elusive entity. Am. Heart J. 1985, 109, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, F.; Scognamiglio, G.; Correra, A.; Merola, A.; Colonna, D.; Palma, M.; Romeo, E.; Sarubbi, B. Pulmonary valve endocarditis in adults with congenital heart disease: The role of echocardiography in a case series. Eur. Heart J. Case Rep. 2020, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, G.; Lancellotti, P.; Erba, P.A.; Sadeghpour, A.; Meshaal, M.; Sambola, A.; Furnaz, S.; Citro, R.; Ternacle, J.; Donal, E.; et al. The ESC-EORP EURO-ENDO (European Infective Endocarditis) registry. Eur. Heart J. Qual. Care Clin. Outcomes 2019, 5, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McElhinney, D.B.; Sondergaard, L.; Armstrong, A.K.; Bergersen, L.; Padera, R.F.; Balzer, D.T.; Lung, T.-H.; Berger, F.; Zahn, E.M.; Gray, R.G.; et al. Endocarditis After Transcatheter Pulmonary Valve Replacement. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 2717–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, R.A. Pulmonic valve endocarditis in a normal heart. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2005, 18, 197–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, G.; Lancellotti, P.; Antunes, M.J.; Bongiorni, M.G.; Casalta, J.-P.; Del Zotti, F.; Dulgheru, R.; El Khoury, G.; Erba, P.A.; Iung, B.; et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 3075–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, G.; Erba, P.A.; Iung, B.; Donal, E.; Cosyns, B.; Laroche, C.; Popescu, B.A.; Prendergast, B.; Tornos, P.; Sadeghpour, A.; et al. Clinical presentation, etiology and outcome of infective endocarditis. Results of the ESC-EORP EURO-ENDO (European infective endocarditis) registry: A prospective cohort study. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 40, 3222–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pant, S.; Patel, N.J.; Deshmukh, A.; Golwala, H.; Patel, N.; Badheka, A.; Hirsch, G.A.; Mehta, J.L. Trends in infective endocarditis incidence, microbiology, and valve replacement in the United States from 2000 to 2011. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 65, 2070–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federspiel, J.J.; Stearns, S.C.; Peppercorn, A.F.; Chu, V.H.; Fowler, V.G. Increasing US Rates of Endocarditis with Staphylococcus aureus: 1999-2008. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012, 172, 363–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.P.; Ferguson, D.A.; Sarubbi, F.A. Corynebacterium striatum: An underappreciated community and nosocomial pathogen. J. Infect. 2005, 50, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.A.; Akhtar, A.; Falah, N.U.; Khan, M. An Unusual Case of Klebsiella pneumoniae Endocarditis. Cureus 2020, 12, e6999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghoribi, M.F.; Alqurashi, M.; Okdah, L.; Alalwan, B.; AlHebaishi, Y.S.; Almalki, A.; Alzayer, M.A.; Alswaji, A.A.; Doumith, M.; Barry, M. Successful treatment of infective endocarditis due to pandrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae with ceftazidime-avibactam and aztreonam. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.K.; Salsano, A.; Giacobbe, D.R.; Popescu, B.A.; Laroche, C.; Duval, X.; Schueler, R.; Moreo, A.; Colonna, P.; Piper, C.; et al. Outcomes of culture-negative vs. culture-positive infective endocarditis: The ESC-EORP EURO-ENDO registry. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 2770–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkenkamp, K.E.; Jin, J.J.; Shivashankar, R.; Jouni, H.; Baddour, L.M.; Blauwet, L.A. Ventricular septal defect and bivalvular endocarditis. Avicenna J. Med. 2015, 05, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnie, A.A.; Miller, N.; Seghatol-Eslami, F. Visualization of bivalvular endocarditis and transeptal cardiac defect via transoesophageal echocardiography. Eur. Heart J. Case Rep. 2021, 5, ytab507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.; Ahmed, F.; Patel, K.; Munir, M.B.; Ghaffar, Y.A.; Mujahid, H.; Balla, S. Isolated Pulmonic Valve Endocarditis: Case Report and Review of Existing Literature on Diagnosis and Therapy. Case 2019, 3, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.A.; Moukarbel, G.V. Isolated Pulmonary Valve Endocarditis. Cardiology 2015, 133, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baddour, L.M.; Wilson, W.R.; Bayer, A.S.; Fowler, V.G., Jr.; Tleyjeh, I.M.; Rybak, M.J.; Barsic, B.; Lockhart, P.B.; Gewitz, M.H.; Levison, M.E.; et al. Infective Endocarditis in Adults: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015, 132, 1435–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaza, N.; Shrestha, N.K.; Gordon, S.; Pettersson, G.B.; Unai, S.; Brizneda, M.V.; Witten, J.C.; Griffin, B.P.; Xu, B. Contemporary Outcomes of Pulmonary Valve Endocarditis: A 16-Year Single Centre Experience. Heart Lung Circ. 2020, 29, 1799–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cremieux, A.-C.; Witchitz, S.; Malergue, M.-C.; Wolff, M.; Vittecocq, D.; Vilde, J.-L.; Frottier, J.; Valere, P.E.; Gibert, C.; Saimot, A.G. Clinical and echocardiographic observations in pulmonary valve endocarditis. Am. J. Cardiol. 1985, 56, 610–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malavia, G.A.; Sharma, S. Pulmonary valve infective endocarditis: A case series. Ann. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2021, 14, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Ma, Y.; Zhai, H.; Miao, Q. Surgical valve repair of isolated pulmonary valve endocarditis. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2012, 16, 384–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.-X.; Zhang, W.-M.; Yu, C.; Zhao, B.-W.; Chen, R.; Pan, M.; Wang, B. Isolated pulmonary valve endocarditis with rapid progression: A case report and literature review. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2021, 16, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaki, J.; Fumoto, H.; Uchino, M.; Nakayama, Y. Isolated Pulmonary Valve Endocarditis Accompanying Multiple Pulmonary Embolisms: Report of a Case. Kyobu Geka 2021, 74, 950–953. [Google Scholar]

- Yepez, C.; Ríos, J. Pulmonary valve reconstruction using Ozaki’s technique for infective endocarditis. Eur. J. Cardio Thorac. Surg. 2020, 59, 917–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, N.; Kariyappa, M.; Kolhari, V.B.; Manjunath, C.N. Cauliflower-like deformation of pulmonary valve in a case of infective endocarditis by a rare organism: Gemella morbillorum. BMJ Case Rep. 2014, 2014, bcr2014204726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amonkar, G.P.; Deshpande, J.R. Infective endocarditis of bicuspid pulmonary valve. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2006, 15, 119–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulahcioglu, S.; Sari, M.; Yilmaz, C.; Kizmaz, Y.U.; Adademir, T.; Ceyran, H. Unexpected isolated native pulmonary valve endocarditis; really benign as thought? J. Card. Surg. 2022, 37, 2120–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhakam, S.; Jafary, F. Pulmonary valve endocarditis. Heart 2003, 89, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trifunovic, D.; Vujisic-Tesic, B.; Obrenovic-Kircanski, B.; Ivanovic, B.; Kalimanovska-Ostric, D.; Petrovic, M.; Boricic-Kostic, M.; Matic, S.; Stevanovic, G.; Marinkovic, J.; et al. The relationship between causative microorganisms and cardiac lesions caused by infective endocarditis: New perspectives from the contemporary cohort of patients. J. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).