Medication Adherence among Patients with Diabetes Mellitus and Its Related Factors—A Real-World Pilot Study in Bulgaria

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design, Setting, Patient Recruitment, and Sample Size

2.2. Characteristics and Cost of Therapy

- n—number of hospitalized patients (12)

- d—number of days out of work (5)

- p—gross domestic product per capita in Bulgaria for 2022 (BGN 18,996.00)

- N—number of working days in 2022 (248)

2.3. Evaluation of Medication Adherence and Quality of Life

2.4. Statistics

2.5. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data and Risk Factors

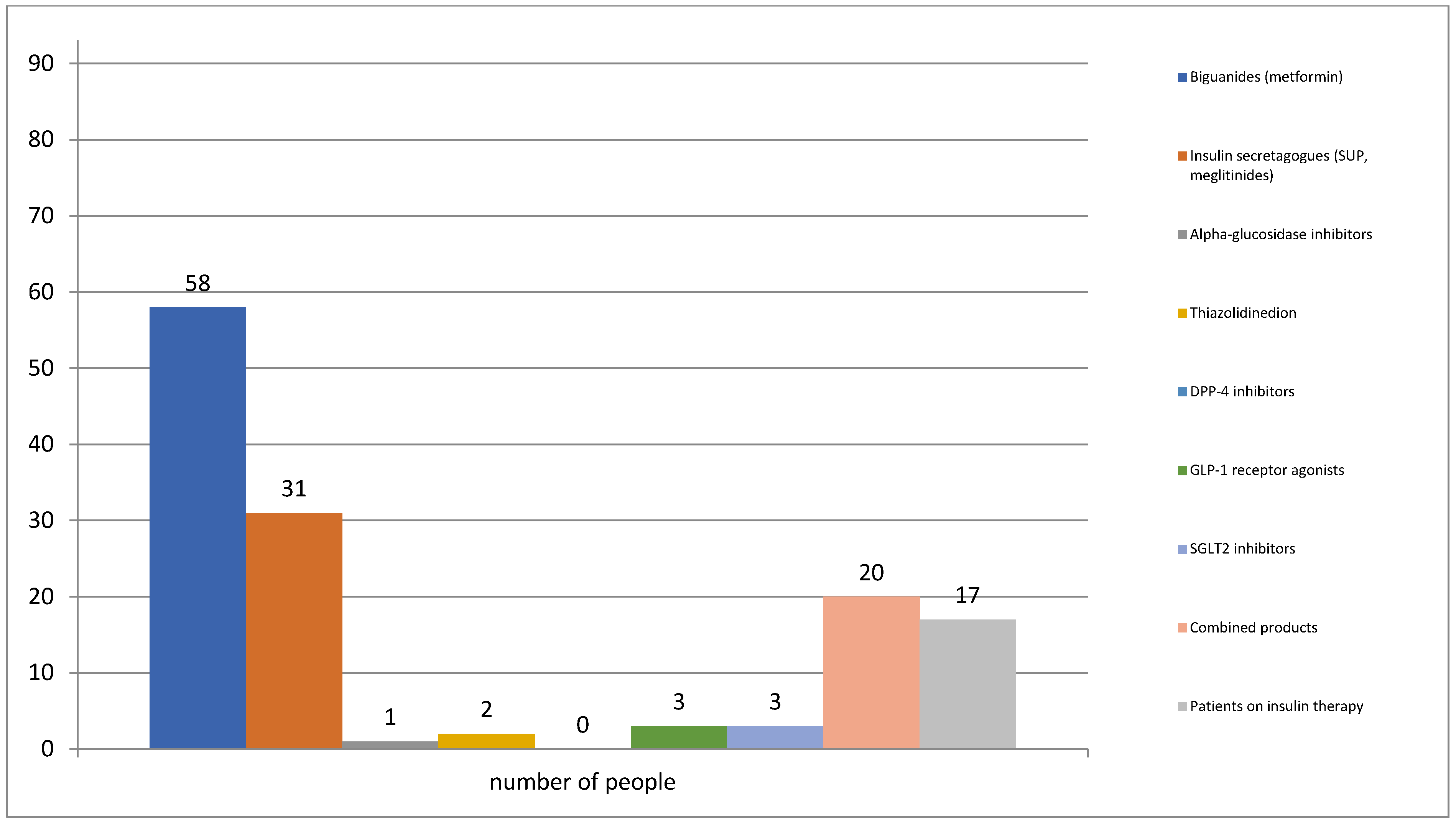

3.2. Pharmacotherapy for Diabetes

3.3. Pharmacotherapy for Concomitant Diseases

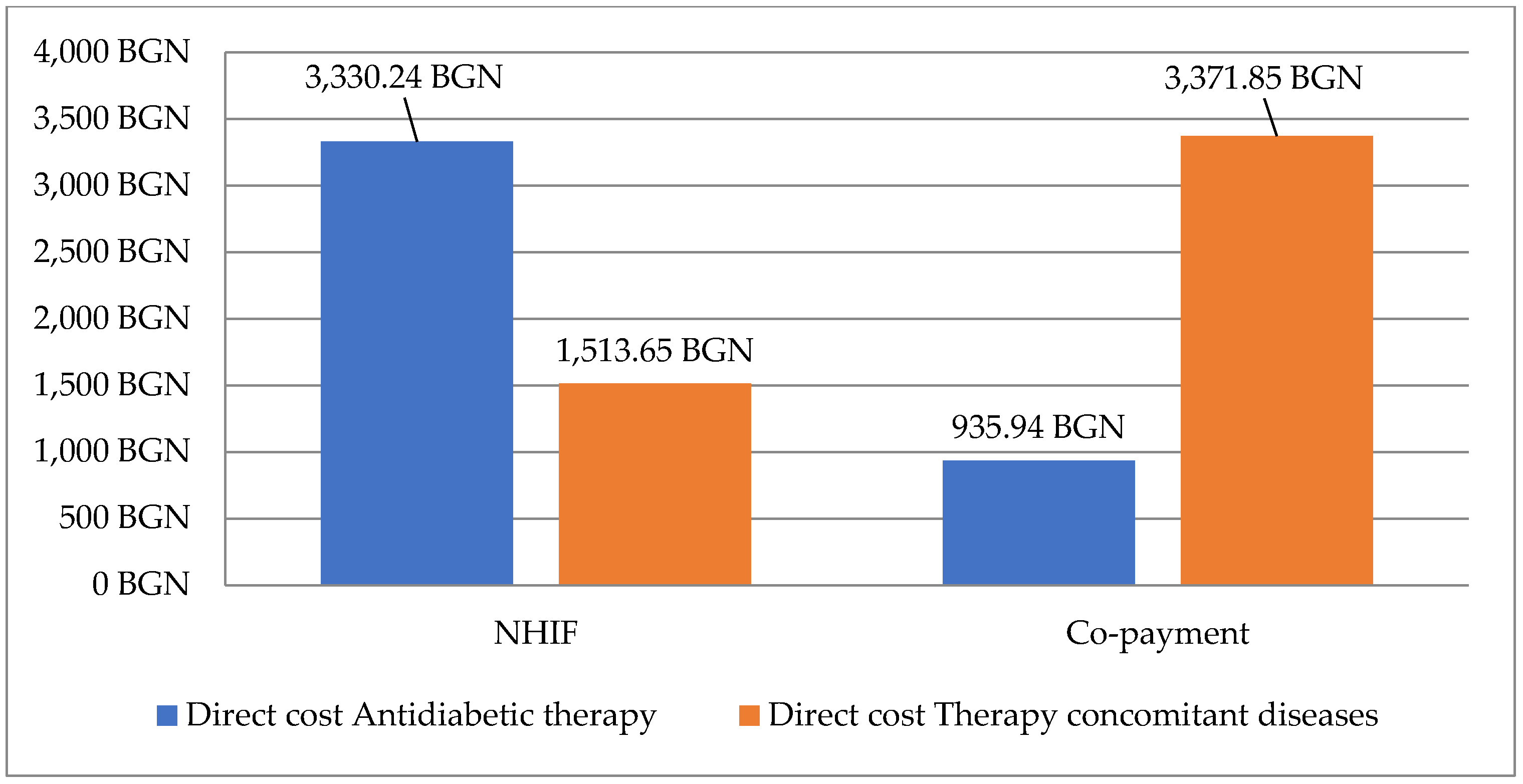

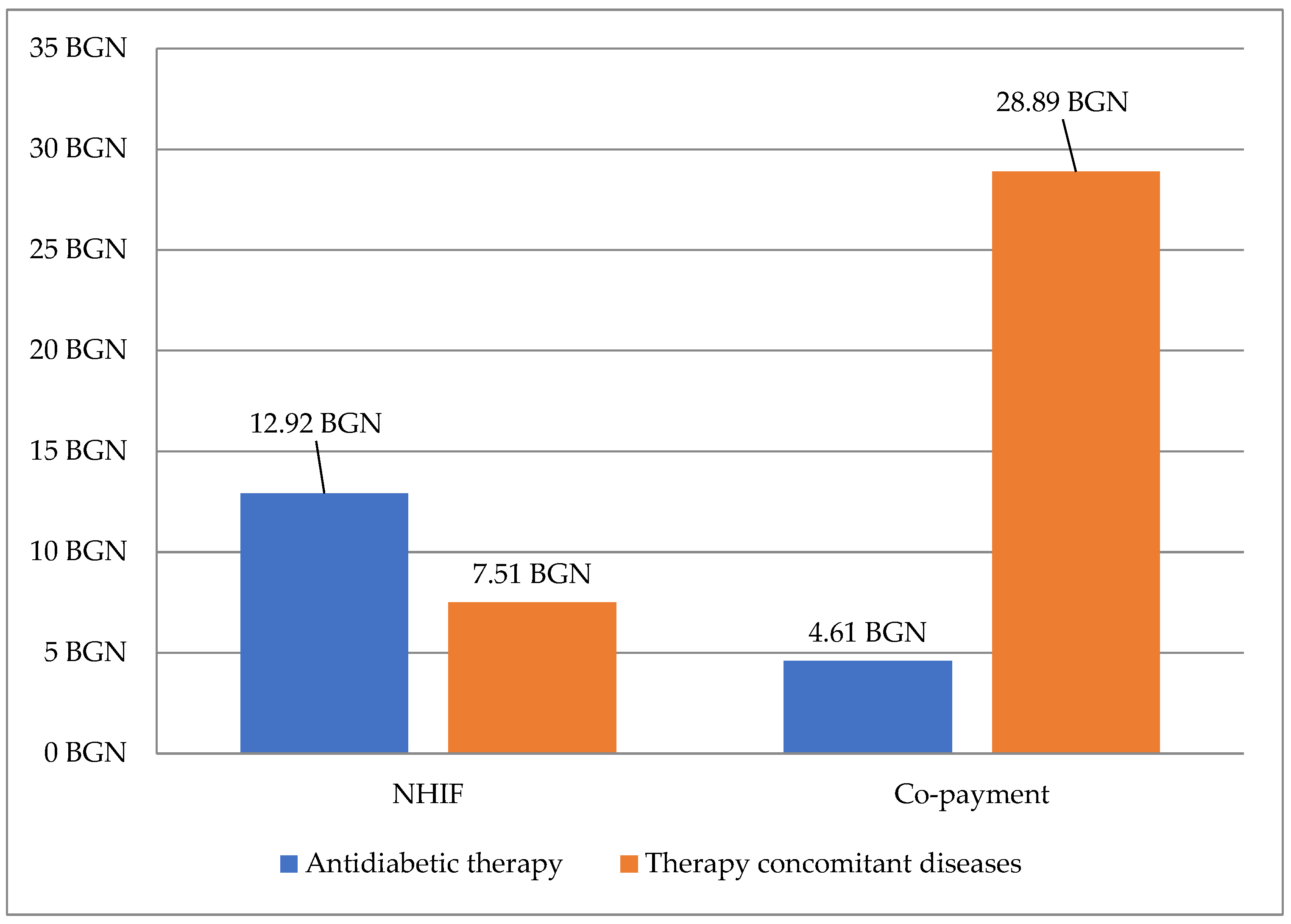

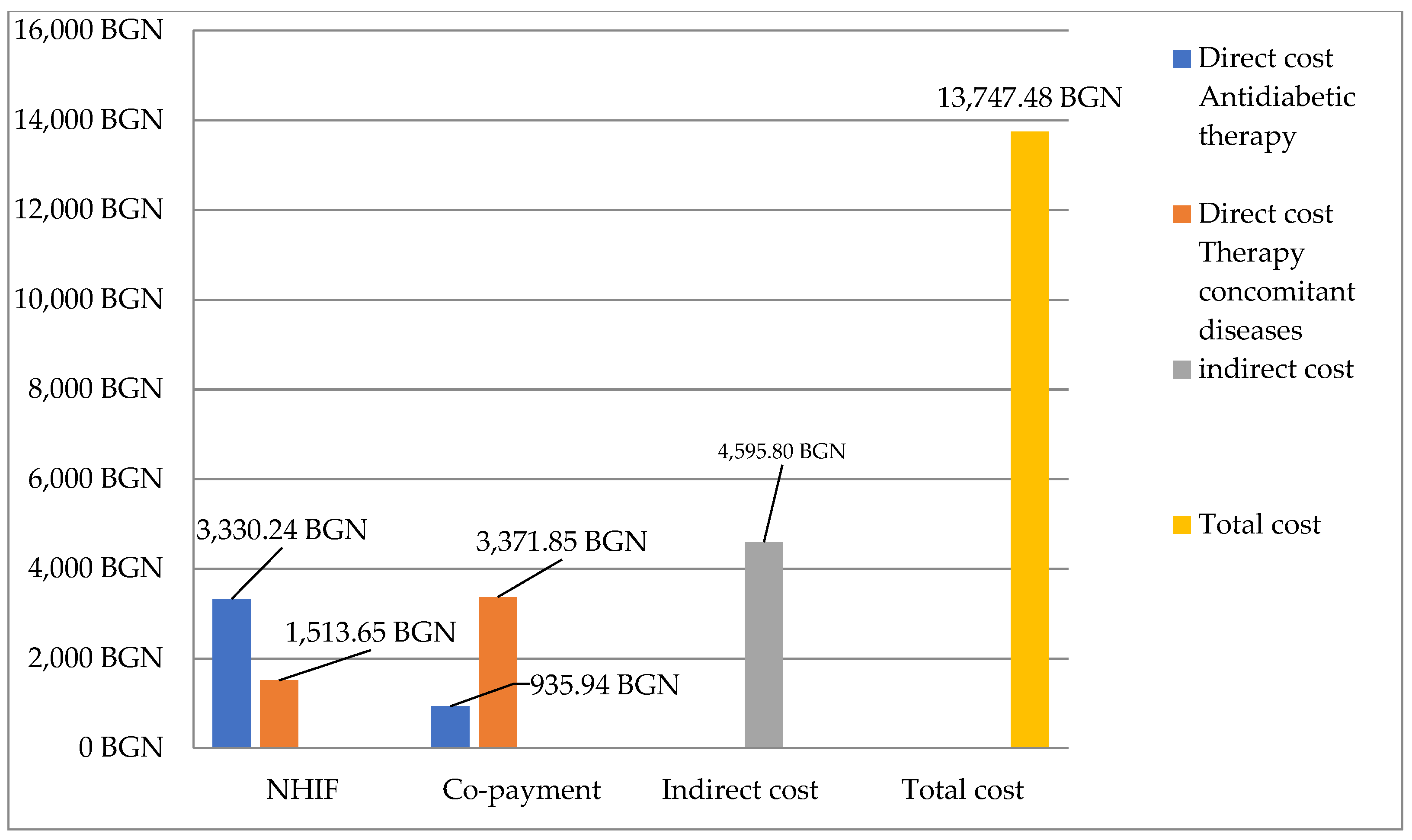

3.4. Costs for Therapy

3.4.1. Direct and Indirect Costs

3.4.2. Total Cost

3.5. Quality of Life

3.6. Level of Medication Adherence and Factors Influencing Medication Adherence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zaharieva, S.; Ministry of Health. Diabetes Awareness Day. 2022. Available online: https://www.mh.government.bg/bg/informaciya-za-grazhdani/svetovni-zdravni-dni/svetoven-den-za-borba-s-diabeta-14-noemvri/ (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Gateva, A. Micro-Macrovascular Complications of Diabetes Mellitus in Patients with Early Disorders in Carbohydrate Metabolism. Ph.D. Thesis, Medical University, Sofia, Bulgaria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tcharaktchiev, D. Creation of a national register of patients with diabetes mellitus. Soc. Med. 2015, 1, 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Christian Bommer, V.S. Global Economic Burden of Diabetes in Adults: Projections from 2015 to 2030. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, J.D. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: The Right to Sight: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob. 2021, 9, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S. What’s in a name? Compliance, adherence and concordance in chronic psychiatric disorders. World J. Psychiatry 2014, 4, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuaid, E.L.; Landier, W. Cultural Issues in Medication Adherence: Disparities and Directions. Gen. Intern. Med. 2018, 33, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwlaat, R.; Wilczynski, N. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014, 2014, CD000011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böhm, A.K.; Schneider, U. Regimen simplification and medication adherence: Fixed-dose versus loose-dose combination therapy for type 2 diabetes. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghikar, S.; Benitez, A. Factors Impacting Adherence to Diabetes Medication Among Urban, Low Income Mexican-Americans with Diabetes. J. Immigr. Minor. Health. 2019, 21, 1334–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pérez, L.Á. Adherence to Therapies in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2013, 4, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimova, A.; Rohova, M.; Atanasova, E.; Kawalec, P.; Czok, K. Drug Policy in Bulgaria. Value Health Reg. Issues 2017, 13C, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Statistical Institute. Available online: https://www.nsi.bg/en (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Beyhaghi, H.; Reeve, B.B.; Rodgers, J.E.; Stearns, S.C. Psychometric Properties of the Four-Item Morisky Green Levine Medication Adherence Scale among Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study Participants. Value Health 2016, 19, 996–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCaffrey, N.; Kaambwa, B.; Currow, D.C.; Ratcliffe, J. Health-related quality of life measured using the EQ-5D–5L: South Australian population norms. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2016, 14, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shams, N.; Amjad, S. Drug Non-Adherence in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus; Predictors and Associations. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad. 2016, 28, 302–307. [Google Scholar]

- Khunti, N. Adherence to type 2 diabetes management. Br. J. Diabetes 2019, 19, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Liu, K. An examination of the socio-demographic correlates of patient adherence to self-management behaviors and the mediating roles of health attitudes and self-efficacy among patients with coexisting type 2 diabetes and hypertension. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerman, I. Adherence to treatment: The key for avoiding long-term complications of diabetes. Arch. Med. Res. 2005, 36, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.; Engberg, S. Adherence to and persistence with antidiabetic medications and associations with clinical and economic outcomes in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic literature review. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2022, 24, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelaw, B.K.; Mohammed, A.; Tegegne, G.T. Nonadherence and contributing factors among ambulatory patients with antidiabetic medications in Adama Referral Hospital. J. Diabetes Res. 2014, 2014, 617041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezie, Y.; Molina, M.; Hernandez, N.; Batista, R.; Niang, S.; Huet, D. Therapeutic compliance: A prospective analysis of various factors involved in the adherence rate in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2006, 32, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; Sharma, S.K.; Verma, R.; Kangra, P.; Dahiya, P.; Kumari, P.; Sahu, P.; Bhakar, P.; Kumawat, R.; Kaur, R.; et al. Medication adherence and quality of life among type-2 diabetes mellitus patients in India. World J. Diabetes. 2021, 12, 1740–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emslie, C.; Hunt, K.; Macintyre, S. How similar are the smoking and drinking habits of men and women in non-manual jobs? Eur. J. Public Health 2002, 12, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, P.A.; Ramsey, S. Alcohol use of diabetes patients: The need for assessment and intervention. Acta Diabetol. 2013, 50, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Jin, C. The Association Between Smoking and Health-Related Quality of Life Among Chinese Individuals Aged 40 Years and Older: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 779789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldenberg, M.; Danovitch, I.; IsHak, W.W. Quality of life and smoking. Am. J. Addict. 2014, 23, 540–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, J.S.; Tanenbaum, M. Psychosocial factors in medication adherence and diabetes self-management: Implications for research and practice. Am. Psychol. 2016, 71, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekgöz, E.; Çolak, S.; Çınar, F.İ.; Yilmaz, S.; Cinar, M. Non-adherence to colchicine treatment is a common misevaluation in familial Mediterranean fever. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 51, 2357–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaham, K.K.; Feyasa, M.B.; Govender, R.D.; Musa, A.M.A.; Al Kaabi, A.J.; El Barazi, I.; Al Sheryani, S.D.; Al Falasi, R.J.; Khan, M. Medication Adherence Among Patients with Multimorbidity in the United Arab Emirates. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2022, 16, 1187–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denicolo, S.E. Non-adherence to antidiabetic and cardiovascular drugs in type 2 diabetes mellitus and its association with renal and cardiovascular outcomes: A narrative review. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2021, 35, 107931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subset | Distribution N (%) | p Value ** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Women | 45 (48.39%) | p = 0.75 |

| Men | 48 (51.61%) | ||

| Age group (years) | Up to 30 years | 1(1.07%) | |

| 30–40 years | - | ||

| 41–50 years | 8(8.6%) | ||

| 50–60 years | 19(20.43%) | ||

| 61–70 years | 20(21.61%) | ||

| over 70 years | 45(48.39%) | ||

| over 50+ years | 84(90.33%) | ||

| Professional status | Working | 39 (41.94%) | p = 0.12 |

| Retirees | 54 (58.06%) | ||

| Type of diabetes | Type 1 | 1 | |

| Type 2 | 92 (98.92%) | ||

| Duration of the disease | Up to 5 years | 36 (38.71%) | |

| 6–10 years | 24 (25.81%) | ||

| 11–15 years | 20 (20.43%) | ||

| 16–20 years | 10 (10.75%) | ||

| Over 21 years | 4 (4.3%) | ||

| Smokers | Women | 13 (28.88%) | p = 0.19 |

| Men | 31 (64.58%) | ||

| Alcohol consumption * | Women | 13 (28.88%) | p = 0.22 |

| Men | 30 (62.50%) | ||

| Control of high blood pressure levels | Women | 36 (80%) | p = 0.92 |

| Men | 37 (77.08%) | ||

| Concomitant diseases | Women | 45 (48.39%) | p = 0.76 |

| Men | 48 (51.61%) |

| Pharmacological Group | Number of Patients | INN * |

|---|---|---|

| Antihypertensives | ||

| ACE inhibitors * | 9 | Perindopril Ramipril |

| AT1 blockers * | 14 | Valsartan Olmesartan |

| Agents affecting the sympathoadrenal system | 66 | Moxonidine Bisoprolol |

| Calcium antagonists | 23 | Felodipine Nifedipine Verapamil |

| Antihypertensive diuretics | 16 | Indapamide Spironolactone Furosemide |

| Combined drugs | 44 | Enalapril/hydrochlorthiazide Valsartan/hydrochlorthiazide |

| Antihyperlipidemic | ||

| Statin | 30 | Rosuvastatin Atorvastatin |

| Cardiac therapy | ||

| Antiarrhythmic | 1 | Propafenone hydrochloride |

| Antianginal | 4 | Molsidomine |

| Anticoagulants | ||

| K1 antagonists | 1 | Acenocoumarol |

| Direct inhibitors of thrombin | 1 | Dabigatran |

| Direct inhibitors of Xa factor | 9 | Apixaban |

| Antiplatelet agents | 7 | Clopidogrel |

| Peripheral vasodilators | ||

| Alpha adrenergic blockers | 6 | Tamsulosin |

| Phosphodiesterase inhibitors | 5 | Pentoxifylline |

| Cerebral vasodilators | 8 | Vinpocetine |

| Combined drugs for benign prostatic hyperplasia | 3 | Solifenacin succinate/tamsulosin Dutasteride/tamsulosin hydrochloride |

| Drugs affecting Polyneuropathies | 14 | Thioctic acid |

| Thyroid treatment | ||

| Thyroid preparations | 10 | Levothyroxine sodium |

| Antiparkinsonian | ||

| Affecting dopaminergic neurotransmission | 1 | Pramipexole |

| Drugs affecting central cholinergic neurotransmission | 1 | Biperiden hydrochloride |

| Combined antiparkinsonian drugs | 1 | Levodopa/benserazide |

| Antiepileptics | 1 | Gabapentin |

| Antipsychotics | 4 | Piracetam |

| Antiglaucoma | ||

| Prostaglandin analogues | 6 | Latanoprost |

| Combined drugs | 3 | Dorzolamide/timolol |

| Gender | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | p Value | |

| EQ-5D-5L | 0.65 ± 0.31 | 0.47 ± 0.31 | 0.063 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Smokers (n = 44) | Nonsmokers (n = 49) | p Value | |

| EQ-5D-5L | 0.62 ± 0.31 | 0.51 ± 0.32 | p = 0.09 |

| VAS | 72.77 ± 14.3 | 63.16 ± 20.45 | p = 0.01 * |

| Alcohol consumption | |||

| Yes (n = 41) | No (n = 52) | p Value | |

| EQ-5D-5L | 0.648 ± 0.31 | 0.49 ± 0.32 | p = 0.017 * |

| VAS | 72.54 ± 15.98 | 63.91 ± 19.34 | p = 0.02 * |

| Medication adherence | |||

| High level | Medium level | p Value | |

| EQ-5D-5L | 0.533 ± 0.32 | 0.602 ± 0.32 | p = 0.33 |

| Medication Adherence (MA) | Weak | Average | High | Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number [%] * | 2 [2.15%] | 31 [33.33%] | 60 [64.52] | 93 |

| MA by gender | ||||

| Men [%] | 0 [0] | 20 [41.67%] | 28 [58.33%] | 48 [51.61%] |

| Women [%] | 2 [4.44%] | 11 [24.44%] | 32 [71.11%] | 45 [48.39%] |

| MA vs. professional status | ||||

| Working [%] | 1 [2.56%] | 17 [43.59%] | 21 [53.85%] | 39 [41.93%] |

| Retired [%] | 1 [1.85%] | 14 [25.93%] | 39 [22.72%] | 54 [58.06%] |

| MA versus number of therapies | ||||

| Monotherapy [%] | 1 [1.97%] | 19 [33.93%] | 36 [29.64%] | 56 [60.22%] |

| Two therapies [%] | 1 [3.13%] | 10 [31.25%] | 21 [65.63%] | 32 [34.4%] |

| Three therapies [%] | 0 [0%] | 2 [40%] | 3 [60%] | 5 [5.38%] |

| Duration of the disease | ||||

| Up to 5 years [%] | 2 [5.71%] | 15 [42.86%] | 18 [51.43%] | 35 [37.63%] |

| 6–10 years [%] | 0 | 9 [37.50%] | 15 [62.50%] | 24 [25.81%] |

| 11–15 years [%] | 0 | 4 [20.00%] | 16 [80%] | 20 [21.51%] |

| 16–20 years [%] | 0 | 3 [30.00%] | 7 [70%] | 10 [10.75%] |

| over 21 years [%] | 0 | 0 | 4 [100%] | 4 [4.3%] |

| Number of comorbidities | ||||

| One concomitant disease [%] | 2 [7.14%] | 7 [25%] | 19 [67.86%] | 28 [30.10%] |

| Two additional concomitant diseases [%] | 0 | 14 [41.18%] | 20 [58.82%] | 34 [36.55%] |

| Three additional concomitant diseases [%] | 0 | 5 [25%] | 15 [75%] | 20 [21.50%] |

| Four additional concomitant diseases [%] | 0 | 3 [37.5%] | 5 [62.50%] | 8 [8.6%] |

| Five additional concomitant diseases [%] | 1 [33.33%] | 1 [33.33%] | 1 [33.33%] | 3 [3.22%] |

| Costs for treatment | ||||

| Paid by patients | 19.52 ± 2.1 | 32.89 ± 23.85 | 37.31 ± 25.56 | |

| Type of therapy | ||||

| Insulin secretagogues | 0 | 2 [16.67%] | 10 [83.3%] | 12 |

| metformin | 0 | 13 [43.3%] | 17 [56.67%] | 30 |

| Insulin secretagogues + metformin | 1 [8.3%] | 5 [41.6%] | 6 [50%] | 12 |

| Determinant | High Level of MA | Medium and Low Level of MA | OR, 95% CI, p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | OR = 1.7582 | ||

| Male | 28 | 20 | 95% CI 0.7418–4.1667 |

| Female | 32 | 13 | p = 0.2 |

| Polypharmacy | OR = 1.3176 | ||

| ≥5 medicines | 35 | 17 | 95% CI 0.5609–3.0955 |

| <5 medicines | 25 | 16 | p = 0.5267 |

| Multimorbidity | OR = 1.4416 | ||

| ≥3 diseases | 22 | 9 | 95% CI 0.5681–3.6578 |

| <3 diseases | 39 | 23 | p = 0.4414 |

| Age | OR = 1.2647 | ||

| <60 years | 17 | 11 | 95% CI 0.5060–3.1610 |

| ≥60 years | 43 | 22 | p = 0.6153 |

| Years lived with diabetes | OR = 3.039 | ||

| <10 years | 33 | 26 | 95% CI 1.1436–8.0759 |

| ≥10 years | 27 | 7 | p = 0.0258 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dinkova, R.; Marinov, L.; Doneva, M.; Kamusheva, M. Medication Adherence among Patients with Diabetes Mellitus and Its Related Factors—A Real-World Pilot Study in Bulgaria. Medicina 2023, 59, 1205. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59071205

Dinkova R, Marinov L, Doneva M, Kamusheva M. Medication Adherence among Patients with Diabetes Mellitus and Its Related Factors—A Real-World Pilot Study in Bulgaria. Medicina. 2023; 59(7):1205. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59071205

Chicago/Turabian StyleDinkova, Rayana, Lyubomir Marinov, Miglena Doneva, and Maria Kamusheva. 2023. "Medication Adherence among Patients with Diabetes Mellitus and Its Related Factors—A Real-World Pilot Study in Bulgaria" Medicina 59, no. 7: 1205. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59071205

APA StyleDinkova, R., Marinov, L., Doneva, M., & Kamusheva, M. (2023). Medication Adherence among Patients with Diabetes Mellitus and Its Related Factors—A Real-World Pilot Study in Bulgaria. Medicina, 59(7), 1205. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59071205