ADHD Follow-Up in Adulthood among Subjects Treated for the Disorder in a Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service from 1995 to 2015

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. ADHD in Adulthood

1.2. ADHD Comorbidities

1.3. ADHD Therapeutic Issues

1.4. Aims

2. Materials and Methods

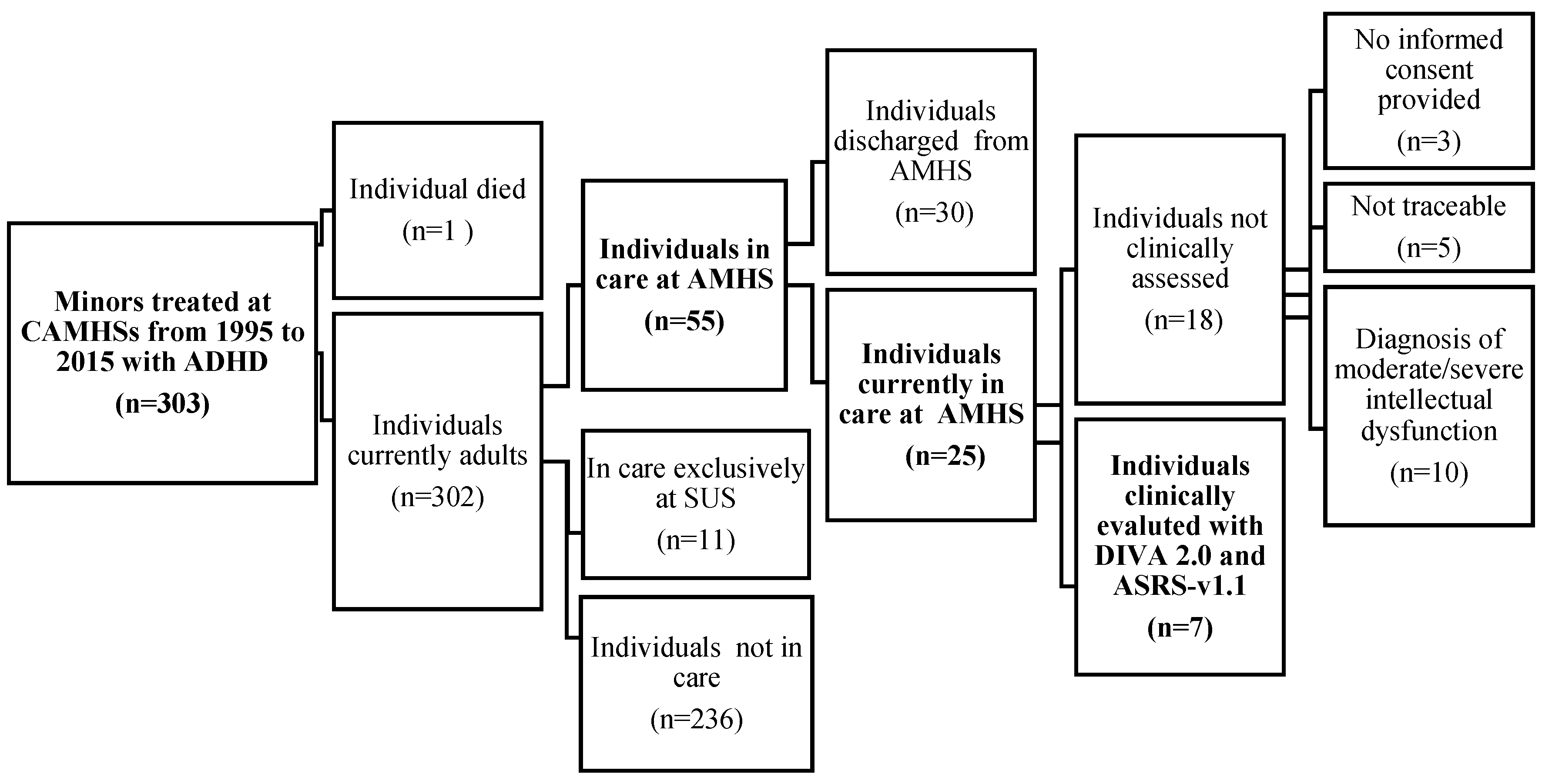

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Exclusion and Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Rating scales

2.4.1. ASRS-V1.1

2.4.2. DIVA 2.0

- the criteria for Attention Deficit (A1);

- the criteria for hyperactivity / impulsivity (A2);

- the age of onset and the dysfunction caused by the symptoms of ADHD.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

3.2. Clinical Characteristics of the Sample

- 60% of the individuals were taken into care before the age of 5;

- in 42% of cases, the referral to CAMHS was made by school;

- most of the minors were treated at CAMHS for a long period of time, ranging between 10 and 15 years in 49% of cases;

- 53% of individuals were treated with only rehabilitative intervention and 47% with multimodal (pharmacological and rehabilitative) treatment;

- 29% of individuals were also in care at Social Service for Minors;

- 89% were discharged from CAMHS at an age ranging between 18 and 21 years;

- 49% of individuals were taken into care by Adult Mental Health Service at the age of majority;

- 58% of the patients treated in CAMHS for ADHD had a psychiatric comorbidity, whereas 27% a neurological comorbidity and 9% a congenital/hereditary type.

- 45% of individuals were still being treated at AMHS (n = 25);

- the majority (n = 36; 65%) of adult individuals appeared to have had their first access to AMHS at an age ranging between 18 and 20 years, 24% of patients between 21 and 24 years, and 6% under 18 years;

- in 49% of cases, the referral to AMHS was CAMHS, in 27% a general practitioner, in 9% spontaneous access, 7% though Social Services, and 6% other sources (judicial referral or at hospital discharge);

- 15% of patients were hospitalized, with a single case (2%) being compulsory hospitalization;

- 15% of patients were sent to a community treatment;

- 7 individuals (13%) had also been treated by SUS and successively discharged;

- 70% of individuals were also in care at Social Services (n = 38);

- 62% of the sample was treated with drug therapy and socio-rehabilitation interventions (n = 34);

- 15% of the sample was treated with a psychotherapy (n = 8);

- 7% of individuals were found to have had legal problems (n = 4);

- 3 individuals were legally supported by a so-called legal administrator.

- no patient was diagnosed with ADHD;

- the diagnosis of intellectual disability represented the most frequent diagnosis (24% of the sample);

- other diagnoses were represented by borderline personality disorders (15%), bipolar disorders (12%), anxiety disorders (9%), schizophrenia spectrum disorders (8%), maladjustment disorders (7%), autism (4%), alcohol/other substance addiction (4%), obsessive-compulsive disorder (2%) and unspecified non-psychotic mental disorders following organic brain damage (2%);

- 7 patients (13%) were evaluated at AMHS, but no psychiatric diagnosis was found during consultation;

- only 12 individuals (22%) presented non-psychiatric medical comorbidities, in particular epilepsy (11%) and obesity (4%).

3.3. Evaluation of ADHD Persistence in Adulthood

- they were not traceable (n = 5);

- they did not provide informed consent (n = 3);

- they were not evaluable due to moderate/severe intellectual dysfunction (n = 10).

- 4 subjects (57%) did not obtain a positive score for adult ADHD;

- 3 subjects (43%) reported symptoms of both ADHD components (inattention and impulsivity/hyperactivity);

- 1 subject (14%) reported symptoms of inattention but not of impulsivity/hyperactivity.

4. Discussion

Limitations and Advantages of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics. New Guidelines for ADHD among Children. 2012. Available online: https://www.apa.org/monitor/2012/03/adhd-guidelines (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- Zuddas, A.; Usala, T.; Masi, G. Il disturbo da deficit di attenzione ed iperattività. In Neuropsicologia dello Sviluppo; Vicari, S., Caselli, M.C., Eds.; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Magnin, E.; Maurs, C. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder during adulthood. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 173, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, S.; Adamo, N.; Ásgeirsdóttir, B.B.; Branney, P.; Beckett, M.; Colley, W.; Cubbin, S.; Deeley, Q.; Farrag, E.; Gudjonsson, G.; et al. Females with ADHD: An expert consensus statement taking a lifespan approach providing guidance for the identification and treatment of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder in girls and women. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, W. Follow-up psychotherapy outcome of patients with dependent, avoidant and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders: A meta-analytic review. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2009, 13, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, R.; Sanders, S.; Doust, J.; Beller, E.; Glasziou, P. Prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2015, 135, e994–e1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lorenzo, R.; Balducci, J.; Poppi, C.; Arcolin, E.; Cutino, A.; Ferri, P.; D’Amico, R.; Filippini, T. Children and adolescents with ADHD followed up to adulthood: A systematic review of long-term outcomes. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2021, 33, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraone, S.V.; Biederman, J.; Mick, E. The age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychol. Med. 2006, 36, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mencacci, C.; Migliarese, G. ADHD nell’adulto. In Dalla Diagnosi al Trattamento [ADHD in Adulthood. From Diagnosis to Treatment]; Edizioni Edra: Milan, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Revised (DSM-III-R), 3rd ed.; American Psychiatric Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, A.M.; Daley, D.; Frydenberg, M.; Houmann, T.; Kristensen, L.J.; Rask, C.; Sonuga-Barke, E.; Søndergaard-Baden, S.; Udupi, A.; Thomsen, P.H. Parent Training for Preschool ADHD in Routine, Specialist Care: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 57, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, J.N.; Loren, R.E. Changes in the Definition of ADHD in DSM-5: Subtle but Important. Neuropsychiatry 2013, 3, 455–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibley, M.H.; Mitchell, J.T.; Becker, S.P. Method of adult diagnosis influences estimated persistence of childhood ADHD: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 1157–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimherr, F.W.; Marchant, B.K.; Gift, T.E.; Steans, T.A.; Wender, P.H. Types of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): Baseline characteristics, initial response, and long-term response to treatment with methylphenidate. ADHD Atten. Deficit Hyperact. Disord. 2015, 7, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tistarelli, N.; Fagnani, C.; Troianiello, M.; Stazi, M.A.; Adriani, W. The nature and nurture of ADHD and its comorbidities: A narrative review on twin studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 109, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooij, J.J.S.; Bijlenga, D.; Salerno, L.; Jaeschke, R.; Bitter, I.; Balázs, J.; Thome, J.; Dom, G.; Kasper, S.; Nunes, F.C.; et al. Updated European Consensus Statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD. Eur. Psychiatry 2019, 56, 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faraone, S.V.; Perlis, R.H.; Doyle, A.E.; Smoller, J.W.; Goralnick, J.J.; Holmgren, M.A.; Sklar, P. Molecular genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 57, 1313–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biederman, J.; Petty, C.R.; Woodworth, K.Y.; Lomedico, A.; Hyder, L.L.; Faraone, S.V. Adult outcome of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A controlled 16-year follow-up study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2012, 73, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.D.; Weiss, J.R. A guide to the treatment of adults with ADHD. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2004, 65, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R.C.; Adler, L.; Ames, M.; Demler, O.; Faraone, S.; Hiripi, E.; Howes, M.J.; Jin, R.; Secnik, K.; Spencer, T.; et al. The World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): A short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychol. Med. 2005, 35, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Kooij, J.J.S.; Kim, B.; Joung, Y.S.; Yoo, H.K.; Kim, E.J.; Lee, S.I.; Bhang, S.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Han, D.H.; et al. Validity of the Korean Version of DIVA-5: A Semi-Structured Diagnostic Interview for Adult ADHD. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 16, 2371–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, L.; Shahrivar, Z.; Alaghband-Rad, J.; Sharifi, V.; Davoodi, E.; Ansari, S.; Emari, F.; Wynchank, D.; Kooij, J.J.S.; Asherson, P. Reliability, Criterion and Concurrent Validity of the Farsi Translation of DIVA-5: A Semi-Structured Diagnostic Interview for Adults With ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 2021, 25, 1666–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caye, A.; Rocha, T.B.M.; Anselmi, L.; Murray, J.; Menezes, A.M.; Barros, F.C.; Gonçalves, H.; Wehrmeister, F.; Jensen, C.M.; Steinhausen, H.C.; et al. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder trajectories from childhood to young adulthood: Evidence from a birth cohort supporting a late-onset syndrome. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzman, M.A.; Bilkey, T.S.; Chokka, P.R.; Fallu, A.; Klassen, L.J. Adult ADHD and comorbid disorders: Clinical implications of a dimensional approach. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Green, J.G.; Adler, L.A.; Barkley, R.A.; Chatterji, S.; Faraone, S.V.; Finkelman, M.; Greenhill, L.L.; Gruber, M.J.; Jewell, M.; et al. Structure and diagnosis of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Analysis of expanded symptom criteria from the Adult ADHD Clinical Diagnostic Scale. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 1168–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayyad, J.; Sampson, N.A.; Hwang, I.; Adamowski, T.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Al-Hamzawi, A.; Andrade, L.H.S.G.; Borges, G.; de Girolamo, G.; Florescu, S.; et al. The descriptive epidemiology of DSM-IV Adult ADHD in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Atten. Defic Hyperact. Disord. 2017, 9, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grevet, E.H.; Bandeira, C.E.; Vitola, E.S.; de Araujo Tavares, M.E.; Breda, V.; Zeni, G.; Teche, S.P.; Picon, F.A.; Salgado, C.A.I.; Karam, R.G.; et al. The course of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder through midlife. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biederman, J.; Monuteaux, M.C.; Spencer, T.; Wilens, T.E.; Faraone, S.V. Do stimulants protect against psychiatric disorders in youth with ADHD? A 10-year follow-up study. Pediatrics 2009, 124, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, R.S.; Kennedy, S.H.; Soczynska, J.K.; Nguyen, H.T.; Bilkey, T.S.; Woldeyohannes, H.O.; Nathanson, J.A.; Joshi, S.; Cheng, J.S.; Benson, K.M.; et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults with bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder: Results from the international mood disorders collaborative project. Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry 2010, 12, PCC.09m00861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamam, L.; Karakus, G.; Ozpoyraz, N. Comorbidity of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder: Prevalence and clinical correlates. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2008, 258, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobanski, E. Psychiatric comorbidity in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 256, 26–31, Erratum in: Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2008, 258, 192–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Cherbuin, N.; Butterworth, P.; Anstey, K.J.; Easteal, S. A population-based study of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and associated impairment in middle-aged adults. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e31500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorlin, E.I.; Dalrymple, K.; Chelminski, I.; Zimmerman, M. Reliability and validity of a semi-structured DSM-based diagnostic interview module for the assessment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in adult psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 242, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, A.J.; Gelernter, J.; Chan, G.; Weiss, R.D.; Brady, K.T.; Farrer, L.; Kranzler, H.R. Correlates of co-occurring ADHD in drug-dependent subjects: Prevalence and features of substance dependence and psychiatric disorders. Addict. Behav. 2008, 33, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retz, W.; Ginsberg, Y.; Turner, D.; Barra, S.; Retz-Junginger, P.; Larsson, H.; Asherson, P. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), antisociality and delinquent behavior over the lifespan. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 120, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. 1992. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37958 (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Doernberg, E.; Hollander, E. Neurodevelopmental Disorders (ASD and ADHD): DSM-5, ICD-10, and ICD-11. CNS Spectr. 2016, 21, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, M.R.; Casado-Lumbreras, C.; Colomo-Palacios, R. ADHD in eHealth—A Systematic Literature Review. Procedia Computer. Sci. 2016, 100, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinipia. Linee-Guida per la Diagnosi e la Terapia Farmacologica del Disturbo da Deficit Attentivo con Iperattività (ADHD) in età Evolutiva. Available online: https://www.sinpia.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/2002_1.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Faraone, S.V.; Larsson, H. Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 2019, 24, 562–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, H.; Chang, Z.; D’Onofrio, B.M.; Lichtenstein, P. The heritability of clinically diagnosed attention deficit hyperactivity disorder across the lifespan. Psychol. Med. 2014, 44, 2223–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, K.L.; Watts, E.L.; Dennis, E.L.; King, L.S.; Thompson, P.M.; Gotlib, I.H. Stressful Life Events, ADHD Symptoms, and Brain Structure in Early Adolescence. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2019, 47, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knopik, V.S.; Sparrow, E.P.; Madden, P.A.; Bucholz, K.K.; Hudziak, J.J.; Reich, W.; Slutske, W.S.; Grant, J.D.; McLaughlin, T.L.; Todorov, A.; et al. Contributions of parental alcoholism, prenatal substance exposure, and genetic transmission to child ADHD risk: A female twin study. Psychol. Med. 2005, 35, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciberras, E.; Mulraney, M.; Silva, D.; Coghill, D. Prenatal Risk Factors and the Etiology of ADHD-Review of Existing Evidence. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, T.R.; Monegro, A.; Nene, Y.; Fayyaz, M.; Bollu, P.C. Neurobiology of ADHD: A Review. Curr. Dev. Disord. Rep. 2019, 6, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, P.; Eckstrand, K.; Sharp, W.; Blumenthal, J.; Lerch, J.P.; Greenstein, D.; Clasen, L.; Evans, A.; Giedd, J.; Rapoport, J.L. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a delay in cortical maturation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007, 104, 19649–19654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M.; Hodgkins, P.; Caci, H.; Young, S.; Kahle, J.; Woods, A.G.; Arnold, L.E. A systematic review and analysis of long-term outcomes in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Effects of treatment and non-treatment. BMC Med. 2012, 10, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N.D.; Wang, G.J.; Tomasi, D.; Kollins, S.H.; Wigal, T.L.; Newcorn, J.H.; Telang, F.W.; Fowler, J.S.; Logan, J.; Wong, C.T.; et al. Methylphenidate-elicited dopamine increases in ventral striatum are associated with long-term symptom improvement in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storebø, O.J.; Krogh, H.B.; Ramstad, E.; Moreira-Maia, C.R.; Holmskov, M.; Skoog, M.; Nilausen, T.D.; Magnusson, F.L.; Zwi, M.; Gillies, D.; et al. Methylphenidate for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: Cochrane systematic review with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses of randomised clinical trials. BMJ 2015, 351, h5203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raman, S.R.; Man, K.K.C.; Bahmanyar, S.; Berard, A.; Bilder, S.; Boukhris, T.; Bushnell, G.; Crystal, S.; Furu, K.; KaoYang, Y.H.; et al. Trends in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder medication use: A retrospective observational study using population-based databases. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 824–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimmsmann, T.; Himmel, W. The 10-year trend in drug prescriptions for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in Germany. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 77, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, T.J.; Brown, A.; Seidman, L.J.; Valera, E.M.; Makris, N.; Lomedico, A.; Faraone, S.V.; Biederman, J. Effect of psychostimulants on brain structure and function in ADHD: A qualitative literature review of magnetic resonance imaging-based neuroimaging studies. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2013, 74, 902–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossmann, J.M.; Mulligan, N.W. Inhibition and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. Am. J. Psychol. 2003, 116, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, A.M.; Oosterlaan, J.; Sergeant, J.A.; Buitelaar, J.K. Executive functioning in adult ADHD: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Med. 2005, 35, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowinckel, A.M.; Alnæs, D.; Pedersen, M.L.; Ziegler, S.; Fredriksen, M.; Kaufmann, T.; Sonuga-Barke, E.; Endestad, T.; Westlye, L.T.; Biele, G. Increased default-mode variability is related to reduced task-performance and is evident in adults with ADHD. Neuroimage Clin. 2017, 16, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, L.E.; Hodgkins, P.; Kahle, J.; Madhoo, M.; Kewley, G. Long-Term Outcomes of ADHD: Academic Achievement and Performance. J. Atten. Disord. 2020, 24, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawaskar, M.; Fridman, M.; Grebla, R.; Madhoo, M. Comparison of Quality of Life, Productivity, Functioning and Self-Esteem in Adults Diagnosed with ADHD and With Symptomatic ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 2020, 24, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faraone, S.V.; Antshel, K.M. ADHD: Non-pharmacologic interventions. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 23, 687–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence—NICE. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Diagnosis and Management. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng87 (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Zadra, E.; Giupponi, G.; Migliarese, G.; Oliva, F.; De Rossi, P.; Gardellin, F.; Scocco, P.; Holzer, S.; Venturi, V.; Sale, A.; et al. Survey on centres and procedures for the diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD in public services in Italy. Riv. Psichiatr. 2020, 55, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Available online: https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/adhd (accessed on 17 December 2022).

- Safren, S.A.; Sprich, S.; Mimiaga, M.J.; Surman, C.; Knouse, L.; Groves, M.; Otto, M.W. Cognitive behavioral therapy vs relaxation with educational support for medication-treated adults with ADHD and persistent symptoms: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010, 304, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, A.P.; Matthies, S.; Graf, E.; Colla, M.; Jacob, C.; Sobanski, E.; Alm, B.; Rösler, M.; Retz, W.; Retz-Junginger, P.; et al. Comparison of Methylphenidate and Psychotherapy in Adult ADHD Study (COMPAS) Consortium. Long-term Effects of Multimodal Treatment on Adult Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms: Follow-up Analysis of the COMPAS Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 3, e194980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, S.; Wilton, L.; Murray, M.L.; Hodgkins, P.; Asherson, P.; Wong, I.C. The epidemiology of pharmacologically treated attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children, adolescents and adults in UK primary care. BMC Pediatr. 2012, 12, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooij, J.J.S.; Francken, M.H. Diagnostisch Interview voor ADHD bij Volwassenen. DIVA Foundation. 2007. Available online: https://www.vanmastrigt.info/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/DiagnostischInterviewVoorADHDbijvolwassenen2007.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Barkley, R.A.; Fischer, M. The unique contribution of emotional impulsiveness to impairment in major life activities in hyperactive children as adults. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2010, 49, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayal, K.; Prasad, V.; Daley, D.; Ford, T.; Coghill, D. ADHD in children and young people: Prevalence, care pathways, and service provision. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, K.D.; Sayal, K.; Hollis, C. ADHD and transitions to adult mental health services: A scoping review. Child Care Health Dev. 2014, 40, 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felt, B.T.; Biermann, B.; Christner, J.G.; Kochhar, P.; Harrison, R.V. Diagnosis and management of ADHD in children. Am. Fam. Physician 2014, 90, 456–464. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt, T.E.; Houts, R.; Asherson, P.; Belsky, D.W.; Corcoran, D.L.; Hammerle, M.; Harrington, H.; Hogan, S.; Meier, M.H.; Polanczyk, G.V.; et al. Is Adult ADHD a Childhood-Onset Neurodevelopmental Disorder? Evidence From a Four-Decade Longitudinal Cohort Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2015, 172, 967–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, B.S.G.; Hinshaw, S.P.; Swanson, J.M.; Arnold, L.E.; Vitiello, B.; Jensen, P.S.; Epstein, J.N.; Hoza, B.; Hechtman, L.; Abikoff, H.B.; et al. The MTA at 8 years: Prospective follow-up of children treated for combined-type ADHD in a multisite study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2009, 48, 484–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hervey, A.S.; Epstein, J.N.; Curry, J.F. Neuropsychology of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analytic review. Neuropsychology 2004, 18, 485–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostert, J.C.; Hoogman, M.; Onnink, A.M.H.; van Rooij, D.; von Rhein, D.; van Hulzen, K.J.E.; Dammers, J.; Kan, C.C.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Norris, D.G.; et al. Similar Subgroups Based on Cognitive Performance Parse Heterogeneity in Adults with ADHD and Healthy Controls. J. Atten. Disord. 2018, 22, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erskine, H.E.; Norman, R.E.; Ferrari, A.J.; Chan, G.C.; Copeland, W.E.; Whiteford, H.A.; Scott, J.G. Long-Term Outcomes of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Conduct Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 55, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, V.; Riglin, L.; Hammerton, G.; Eyre, O.; Martin, J.; Anney, R.; Thapar, A.; Rice, F. What explains the link between childhood ADHD and adolescent depression? Investigating the role of peer relationships and academic attainment. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 29, 1581–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriyan, A.B.; Pelham, W.E., Jr.; Molina, B.S.; Waschbusch, D.A.; Gnagy, E.M.; Sibley, M.H.; Babinski, D.E.; Walther, C.; Cheong, J.; Yu, J.; et al. Young adult educational and vocational outcomes of children diagnosed with ADHD. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2013, 41, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, B.S.; Pelham, W.E.; Gnagy, E.M.; Thompson, A.L.; Marshal, M.P. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder risk for heavy drinking and alcohol use disorder is age specific. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2007, 31, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudjonsson, G.H.; Wells, J.; Young, S. Personality disorders and clinical syndromes in ADHD prisoners. J. Atten. Disord. 2012, 16, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez, N.; Dey, M.; Eich-Höchli, D.; Foster, S.; Gmel, G.; Mohler-Kuo, M. Adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and its association with substance use and substance use disorders in young men. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2016, 25, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamboni, L.; Marchetti, P.; Congiu, A.; Giordano, R.; Fusina, F.; Carli, S.; Centoni, F.; Verlato, G.; Lugoboni, F. ASRS Questionnaire and Tobacco Use: Not Just a Cigarette. A Screening Study in an Italian Young Adult Sample. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valsecchi, P.; Nibbio, G.; Rosa, J.; Tamussi, E.; Turrina, C.; Sacchetti, E.; Vita, A. Adult ADHD: Prevalence and Clinical Correlates in a Sample of Italian Psychiatric Outpatients. J. Atten. Disord. 2021, 25, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, J.E.; Viner, R.M. Lost in transition? Between paediatric and adult services. BMJ 2006, 332, 435–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopson, B.; Eckenrode, M.; Rocque, B.G.; Blount, J.; Hooker, E.; Rediker, V.; Cao, E.; Tofil, N.; Lau, Y.; Somerville, C.S. The development of a transition medical home utilizing the individualized transition plan (ITP) model for patients with complex diseases of childhood. Disabil. Health J. 2022, 101427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allemang, B.; Samuel, S.; Pintson, K.; Patton, M.; Greer, K.; Farias, M.; Schofield, K.; Sitter, K.C.; Patten, S.B.; Mackie, A.S.; et al. “They go hand in hand”: A patient-oriented, qualitative descriptive study on the interconnectedness between chronic health and mental health conditions in transition-age youth. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, T. Transitional care for young adults with ADHD: Transforming potential upheaval into smooth progression. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, e87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Emmerik-van Oortmerssen, K.; Blankers, M.; Vedel, E.; Kramer, F.; Goudriaan, A.E.; van den Brink, W.; Schoevers, R.A. Prediction of drop-out and outcome in integrated cognitive behavioral therapy for ADHD and SUD: Results from a randomized clinical trial. Addict. Behav. 2020, 103, 106228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Motivations for Conclusion of Treatment at CAMHS | Subjects, n (%) |

|---|---|

| CAMHS ordinary discharge | 187 (78.9%) |

| CAMHS self-discharge | 34 (14.3%) |

| Referral to AMHS | 55 (18%) |

| Referral to another service (Social Service or Disability Service) | 12 (5.1%) |

| Transfer to another town/country | 3 (1.2%) |

| Deceased | 1 (0.4%) |

| Variables | Patients with a Positive Score (≥6) at One or Two Dimensions of DIVA 2.0 (n = 4) (57%) | Patients with a Negative Score (<6) at Both Dimensions of DIVA 2.0 (n = 3) (43%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age at treatment start (years: mean ± SD) | 5.25 ± 2.98 | 6 ± 0 ** |

| Referral to CAMHS from | ||

| School | 2 (50%) | 2 (75%) |

| Minors Social Services | 1 (25%) | 0 |

| Doctor of General Medicine/other specialists | 1 (25%) | 1 (25%) |

| Length of treatment at CAMHS (years: mean ± SD) | 12.5 ± 3.11 | 10 ± 2.83 |

| Treatment | ||

| Rehabilitation | 0 | 1 (25%) |

| Multimodal (Pharmacological and Rehabilitation) | 4 (100%) | 2 (75%) |

| In care at several services | 4 | 2 * |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 2 (50%) | 1 (25%) |

| Female | 2 (50%) | 2 (75%) |

| Age (years: mean ± SD) | 21.25 ± 1.71 | 25 ± 1.73 § |

| Nationality | ||

| Italian | 3 (75%) | 3 (100%) |

| Not Italian | 1 ((25%) | 0 |

| School | ||

| Secondary school | 3 (75%) | 0 |

| High school | 1 (25%) | 3 (100%) |

| Employment | ||

| Employed | 0 | 1 (25%) |

| Protected job placement | 2 (50%) | 2 (75%) |

| Civil invalidity | 1 (25%) | 0 |

| Unemployed | 1 (25%) | 0 |

| Housing | ||

| Parental Family | 3 (75%) | 2 (75%) |

| Alone | 1 (25%) | 0 |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 (25%) |

| Main Psychiatric Diagnosis | ||

| Intellectual Disability | 0 | 2 (75%) |

| Personality Disorders | 0 | 1 (25%) |

| Conduct Disorder | 2 (50%) | 0 |

| Bipolar Disorders | 1 (25%) | 0 |

| None | 1 (25%) | 0 |

| Period in therapeutic communities | 1 (25%) | 0 |

| In care at Social Service | 3 (75%) | 2 (75%) |

| Legal issues | ||

| Yes | 1 (25%) | 1 (25%) |

| Legal administrator | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Di Lorenzo, R.; Balducci, J.; Cutino, A.; Latella, E.; Venturi, G.; Rovesti, S.; Filippini, T.; Ferri, P. ADHD Follow-Up in Adulthood among Subjects Treated for the Disorder in a Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service from 1995 to 2015. Medicina 2023, 59, 338. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59020338

Di Lorenzo R, Balducci J, Cutino A, Latella E, Venturi G, Rovesti S, Filippini T, Ferri P. ADHD Follow-Up in Adulthood among Subjects Treated for the Disorder in a Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service from 1995 to 2015. Medicina. 2023; 59(2):338. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59020338

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Lorenzo, Rosaria, Jessica Balducci, Anna Cutino, Emanuela Latella, Giulia Venturi, Sergio Rovesti, Tommaso Filippini, and Paola Ferri. 2023. "ADHD Follow-Up in Adulthood among Subjects Treated for the Disorder in a Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service from 1995 to 2015" Medicina 59, no. 2: 338. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59020338

APA StyleDi Lorenzo, R., Balducci, J., Cutino, A., Latella, E., Venturi, G., Rovesti, S., Filippini, T., & Ferri, P. (2023). ADHD Follow-Up in Adulthood among Subjects Treated for the Disorder in a Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service from 1995 to 2015. Medicina, 59(2), 338. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59020338