4. Discussion

The XEN45 gel stent has been recognized as a safe and effective micro-invasive glaucoma surgery procedure, even in advanced and refractory glaucoma [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Intraoperative adjunctive MMC and postoperative needling revision using anti-fibrotic agents are widely used in XEN gel stent implantation for wound modulation and the prevention of bleb fibrosis [

1,

2,

3,

4]. These procedures might be associated with the possibility of postoperative bleb-related complications, including over-filtering blebs, blebitis, bleb dysesthesia, bleb leakage, and endophthalmitis [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. However, reports on XEN exposure and its management are limited [

5,

6,

9].

In our patient, XEN gel stent exposure and conjunctival erosion were observed at 18 months postoperatively. The detection timing for stent exposure or extrusion varied from 1 month to 14 months in previous case reports. Arnould et al. reported recurrent XEN exposure three months postoperatively (two months after needling revision) [

5]. Lapira al. reported extrusion and breakage of an XEN stent with endophthalmitis 3.5 months postoperatively [

6]. Similarly, Karri et al. reported endophthalmitis following XEN stent exposure postoperatively after 4 months [

7]. Kingston et al. reported that infective necrotizing scleritis developed 14 months after the initial surgery [

8].

Possible mechanisms for the initial conjunctival erosions are as follows: (1) the use of the anti-metabolite MMC; (2) the ab interno approach; (3) the subconjunctival position; (4) the long-term use of topical anti-glaucoma medications; and (5) mechanical stress, such as the elderly patient rubbing the eye with their hands. First, the use of anti-metabolites enhances the success rate of filtering surgery by reducing the wound-healing process. However, the use of anti-metabolites might also increase the risk of bleb-related complications, such as a thin-walled cystic bleb, or surgically induced necrotizing scleritis [

4,

5,

6,

8]. In this patient, we used a 0.1 mL subconjunctival injection of 0.02% MMC. Second, the ab interno approach may also contribute to conjunctival erosions [

4,

5,

6,

7]. In XEN gel stent implantation with an ab externo approach and conventional trabeculectomy, MMC is usually applied using MMC-soaked cellulose sponges and wash-out. However, these procedures are not applicable with an ab interno approach, because the MMC is injected directly into the subconjunctival space and remains in this space at the end of surgery without washout [

3,

4,

6]. This difference in the approach may cause more vulnerable and avascular bleb formation. Third, we considered the positioning of the XEN subconjunctival space versus sub-Tenon’s space [

3]. In this case, the XEN gel implant was placed in the subconjunctival space. Compared to sub-Tenon’s position, a subconjunctival placement may have a higher risk of micro-trauma and subsequent infection, whereas sub-Tenon’s placement has a higher chance of the tip of the stent becoming entangled in Tenon’s position and subsequent bleb failure [

4,

7]. Long-term use of topical drugs can induce changes in the conjunctiva and ocular surface, including conjunctival thinning and metaplasia. These qualitative changes and conjunctival thinning may also contribute to conjunctival erosion.

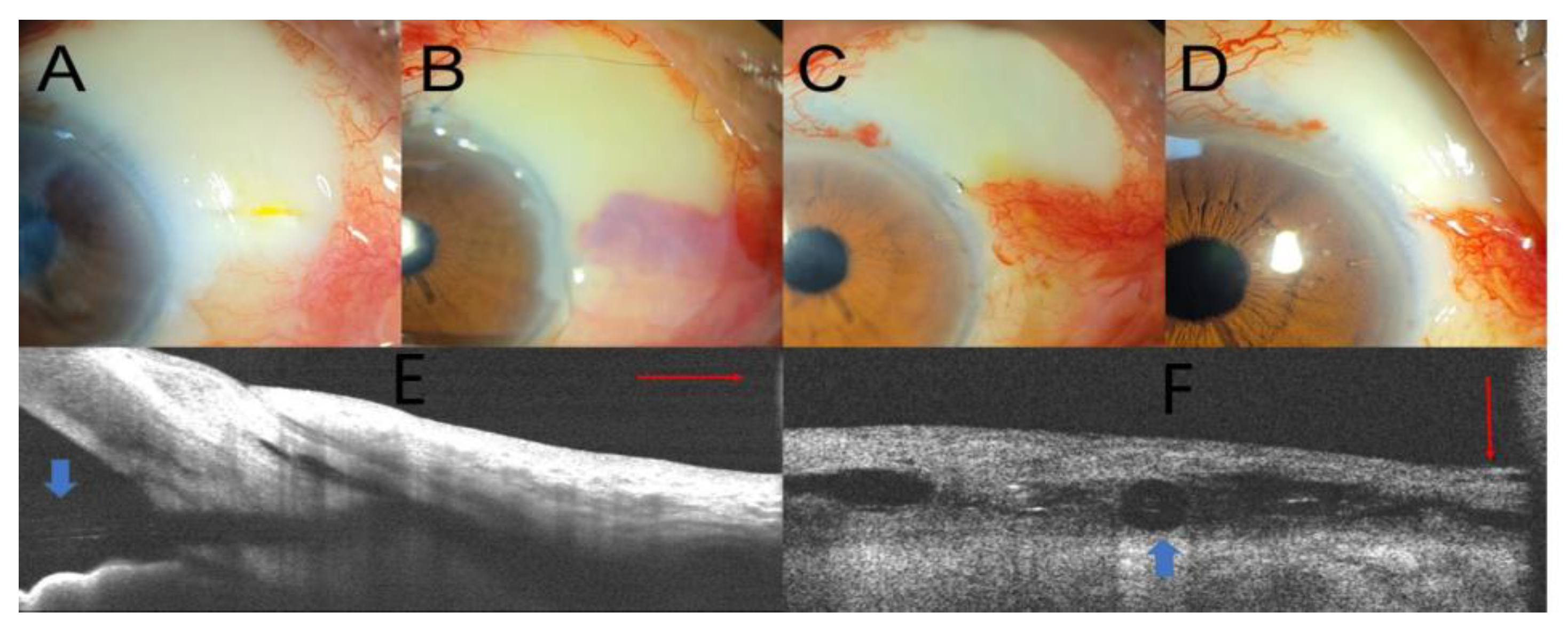

In addition to pre-existing risk factors that might contribute to the formation of avascular thin blebs, mechanical stress could have aggravated conjunctival injury due to foreign-body sensation in this elderly patient [

6] with degenerative conjunctival changes, such as Meibomian gland dysfunction, decreased tear film volume, tear film instability, and coexisting ocular disease with diabetes and hypertension. Based on AS-OCT examination, we hypothesized that all these mechanisms might induce XEN gel stent exposure with conjunctival erosion. Similarly, Arnould et al. suggested that morphological changes in OCT after XEN gel stent implantation may help guide bleb revision and the management of conjunctival erosion and device extrusion [

5]. In our case, AS-OCT examination demonstrated XEN gel stent exposure without conjunctival coverage and surgical results. In this context, the proper use of AS-OCT for evaluating and monitoring bleb morphology could provide additional information regarding XEN gel stent positioning, bleb morphology, and the status of the conjunctiva or Tenon’s capsule.

Various conservative treatment options, such as pressure patching, contact lenses, topical lubricants, autoserums, and ointments, have been considered to resolve these problems [

4,

5,

8,

9]. However, in our patient, conservative treatment was unsuccessful. Therefore, we decided to perform surgical bleb revision. Arnould et al. [

5] reported excision of a scarred bleb, free conjunctival graft, XEN gel stent trimming by 1.5 mm and complementary amniotic graft. Kingston et al. reported removal of the XEN gel stent, Tutoplast plugging into the scleral opening, amniotic membrane graft over the ischemic scleral bed, and fixation to healthy conjunctival and limbal tissues. [

8] Another study reported ab interno repositioning of the stent through the anterior chamber and direct suturing of the conjunctival defect [

9].

We performed combination treatment (rotational conjunctival flap and amniotic membrane transplantation). This management comprised three aspects: (1) dealing with wound leakage, (2) the facilitation of wound healing, and (3) minimal manipulation of the XEN gel stent itself. First, a rotational conjunctival flap was used because the conjunctival local flap (advancement or rotational flap) has been shown to provide successful resolution of bleb-associated complications in conventional filtration surgery [

4,

10]. In our case, the conjunctiva surrounding the XEN exposure with conjunctival defect also revealed a thin avascular bleb. We consider that free grafts alone, without bleb resection, may have a higher risk of recurrence of bleb leak and structural weakness in another harvested quadrant [

4,

5]. The conjunctival advancement flap had the possibility of excessive traction force [

4] and lower filtering bleb height in our patient. Second, the amniotic membrane could act as a biological bandage contact lens to decrease mechanical stress and promote wound healing via anti-inflammatory action, anti-scarring action, and various growth factors such as EGF, NGF, and IGF [

11]. In our patient, the amniotic membrane was sutured to cover both healthy host tissue and the site of interest, including thin avascular blebs and a conjunctival flap overlying the conjunctival defect. Liu et al. suggested that an ideal procedure for repairing bleb leaks is to support fragile conjunctival tissue and suppress exaggerated bleb scarring [

11]. In this regard, AM has exhibited promising results in repairing bleb leak regardless of the epithelial side being up or down, over or under the conjunctiva, or with or without bleb excision after trabeculectomy [

11]. Third, we attempted to perform minimal manipulation of the XEN gel stent itself. The flexibility and properties of stents differ depending on collagen hydration. Moreover, the XEN gel stent is designated as the ratio of the length to the lumen diameter (6 mm to 45 µm) to regulate optimal outflow, considering the Hagen–Poiseuille law [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The direct manipulation of hydrated collagen stents might pose a risk of breakage or cutting [

4,

6]. Thus, we adopted a rotational conjunctival flap and amniotic membrane patch graft using fibrin glue to minimize suture-induced inflammation, and an oversized temporary complimentary amniotic membrane using 10-0 continuous nylon sutures.

This study has some limitations. First, the results of our case report should be confirmed in a larger series, and our case reports provide excellent ocular surface reconstruction and acceptable IOP control without bleb leakage. Second, long-term follow-up is needed to monitor the ocular surface, considering the possibility of recurrent leakage despite minimal manipulation of the XEN gel stent.

This case report highlights the importance of careful examination, including slit-lamp examination, the Seidel test, and AS-OCT, to identify accurate anatomical positioning and to monitor ocular surface changes after XEN gel stent implantation with MMC or 5-FU. We also demonstrate the potential complications of XEN gel stent exposure and its management in addition to previously reported surgical techniques [

5,

8,

9]. Thus, ophthalmic surgeons should also consider the optimal concentration of MMC according to the approach methods and patient profile, such as age, race, and previous surgical history, which determine the anticipated scarring tendency [

3].