Congenital Sensorineural Hearing Loss and Inborn Pigmentary Disorders: First Report of Multilocus Syndrome in Piebaldism

Abstract

1. Introduction

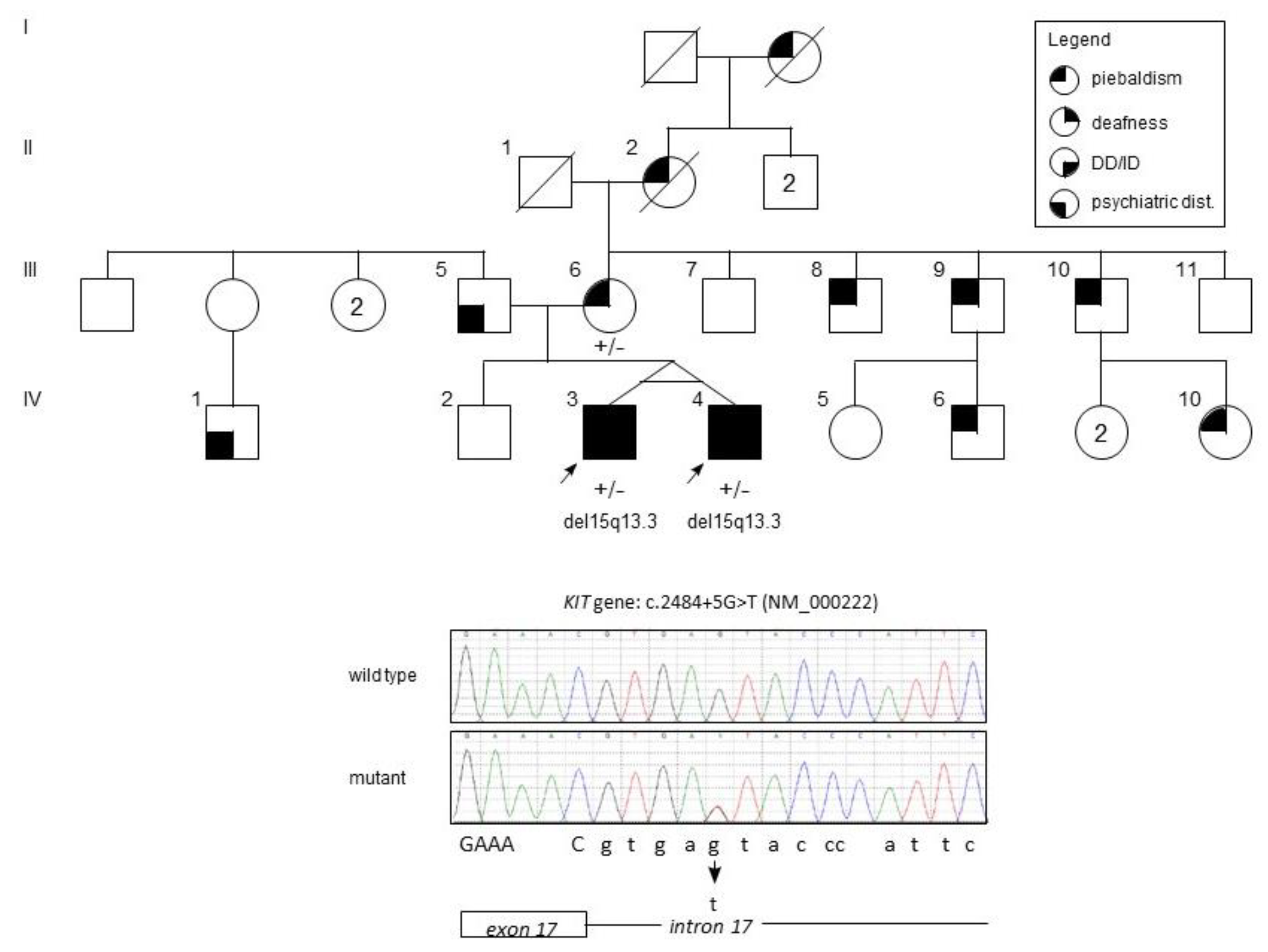

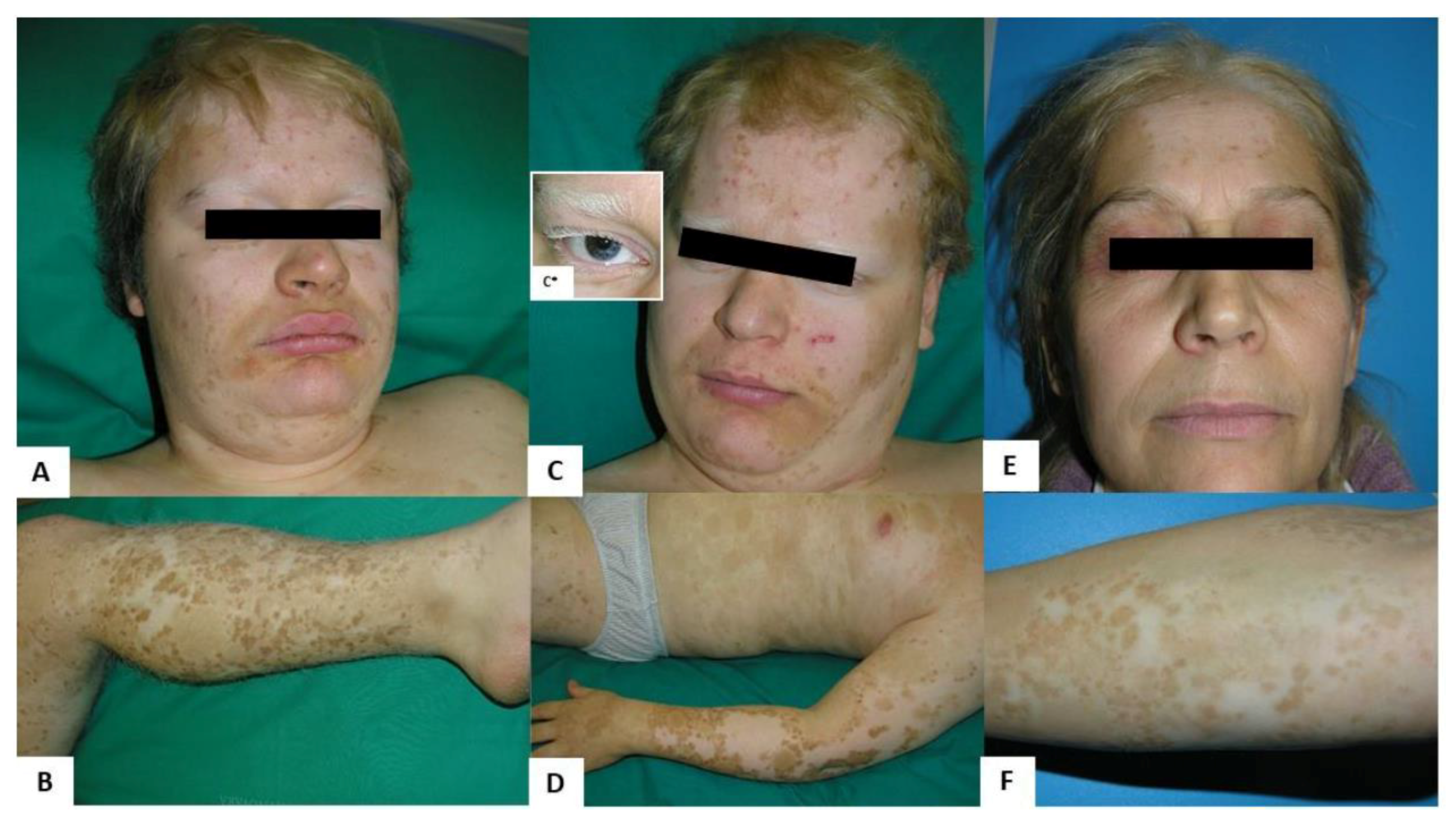

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Clinical Findings

2.2. Materials and Methods

2.3. Genetic Findings

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mayor, R.; Theveneau, E. The neural crest. Development 2013, 140, 2247–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, Y.; Sipp, D.; Enomoto, H. Tissue interactions in neural crest cell development and disease. Science 2013, 341, 860–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.D. Overview of genetic auditory syndromes. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 1995, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mort, R.L.; Jackson, I.J.; Patton, E.E. The melanocyte lineage in development and disease. Development 2015, 142, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koffler, T.; Ushakov, K.; Avraham, K.B. Genetics of Hearing Loss: Syndromic. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 48, 1041–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fistarol, S.K.; Itin, P.H. Disorders of pigmentation. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2010, 8, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Feng, Y.; Acke, F.R.; Coucke, P.; Vleminckx, K.; Dhooge, I.J. Hearing loss in Waardenburg syndrome: A systematic review. Clin. Genet. 2016, 89, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izumi, K.; Kohta, T.; Kimura, Y.; Ishida, S.; Takahashi, T.; Ishiko, A.; Kosaki, K. Tietz syndrome: Unique phenotype specific to mutations of MITF nuclear localization signal. Clin. Genet. 2008, 74, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oiso, N.; Fukai, K.; Kawada, A.; Suzuki, T. Piebaldism. J. Dermatol. 2013, 40, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kouarty, H.; Dakhama, B.S. Piebaldism: A pigmentary anomaly to recognize: About a case and review of the literature. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2016, 25, 155. [Google Scholar]

- Kansal, N.K.; Agarwal, S. Association of Piebaldism with Café-au-Lait Macules. Skinmed 2017, 15, 223–225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spritz, R.A.; Beighton, P. Piebaldism with deafness: Molecular evidence for an expanded syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1998, 75, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultén, M.A.; Honeyman, M.M.; Mayne, A.J.; Tarlow, M.J. Homozygosity in piebald trait. J. Med. Genet. 1987, 24, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilsby, A.J.; Cruwys, M.; Kukendrajah, C.; Russell-Eggitt, I.; Raglan, E.; Rajput, K.; Lohse, P.; Brady, A.F. Homozygosity for piebaldism with a proven KIT mutation resulting in depigmentation of the skin and hair, deafness, developmental delay and autism spectrum disorder. Clin. Dysmorphol. 2013, 22, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lezirovitz, K.; Nicastro, F.S.; Pardono, E.; Abreu-Silva, R.S.; Batissoco, A.C.; Neustein, I.; Spinelli, M.; Mingroni-Netto, R.C. Is autosomal recessive deafness associated with oculocutaneous albinism a “coincidence syndrome”? J. Hum. Genet. 2006, 51, 716–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 54, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziats, M.N.; Goin-Kochel, R.P.; Berry, L.N.; Ali, M.; Ge, J.; Guffey, D.; Rosenfeld, J.A.; Bader, P.; Gambello, M.J.; Wolf, V.; et al. The complex behavioral phenotype of 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome. Genet. Med. 2016, 18, 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppman-Chaney, N.; Wain, K.; Seger, P.R.; Superneau, D.W.; Hodge, J.C. Identification of single gene deletions at 15q13.3: Further evidence that CHRNA7 causes the 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome phenotype. Clin. Genet. 2013, 83, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinawi, M.; Schaaf, C.P.; Bhatt, S.S.; Xia, Z.; Patel, A.; Cheung, S.W.; Lanpher, B.; Nagl, S.; Herding, H.S.; Nevinny-Stickel, C.; et al. A small recurrent deletion within 15q13.3 is associated with a range of neurodevelopmental phenotypes. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 1269–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posey, J.E.; Harel, T.; Liu, P.; Rosenfeld, J.A.; James, R.A.; Coban Akdemir, Z.H.; Walkiewicz, M.; Bi, W.; Xiao, R.; Ding, Y.; et al. Resolution of Disease Phenotypes Resulting from Multilocus Genomic Variation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retterer, K.; Juusola, J.; Cho, M.T.; Vitazka, P.; Millan, F.; Gibellini, F.; Vertino-Bell, A.; Smaoui, N.; Neidich, J.; Monaghan, K.G.; et al. Clinical application of whole-exome sequencing across clinical indications. Genet. Med. 2016, 18, 696–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name of Syndrome | Genetic Disorder 1 | Frequency | Clinical Findings 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin and Cutaneous Annexes | Non-Cutaneous | |||

| Waardenburg Syndrome, Type 1 | WS1 AD Gene PAX3 (2q36.1) | Incidence 1:20,000–40,000 births (3–5% of congenital SNHL) | Poliosis (45%) Early graying of the scalp hair (45%) Congenital leukoderma (30%): white skin patches on the face, trunk, or limbs; hyperpigmented borders may be present | Facial dysmorphism: Dystopia canthorum (100%): lateral displacement of the inner canthi, high nasal root (50–100%), medial eyebrow flare (60–70%) Eyes: Heterochromia iridium (15–30%), hypoplastic or brilliant blue irides (15%) Neurological signs: SNHL (60%) Occasional findings: spina bifida, cleft lip and palate |

| Waardenburg Syndrome, Type 2 | WS2 AD Genes MITF 15–20% (3p14-p13) SOX10 15% (22q13.1) SNAI2 very rare (8q11.21) | Poliosis (15–30%) Early graying of the scalp hair (30%) Congenital leukoderma (5–12%) | Facial dysmorphism: Dystopia canthorum not present (0%), high nasal root (0–14%), medial eyebrow flare (10%) Neurological signs: SNHL (80–90%) Eyes: Heterochromia iridium/(50%), hypoplastic blue irides (3–23%) Kallmann syndrome (anosmia, hypogonadism) in carriers of mutation in SOX10 gene Occasional findings: temporal bone abnormalities, ganglionic megacolon, abnormality of the kidney and/or the pulmonary artery, ptosis, telecanthus | |

| Waardenburg syndrome, Type 3 (Klein–Waardenburg syndrome) | WS3 AD/AR Gene PAX3 (2q36.1) The rarest form of all WS types | Hypopigmentation abnormalities of hair and skin like WS1 | Facial dysmorphism: like WS1 Eyes: like WS1, blepharophimosis (80–100%) Neurological signs: SNHL, microcephaly (80–100%) Limb anomalies: hypoplasia of the musculoskeletal system, flexion contractures, carpal bone fusion, syndactyly (80–100%) | |

| Waardenburg syndrome, Type 4 (Waardenburg-Shah syndrome) | WS4 AR Genes EDNRB (13q22.3) EDN3 (20q13.32) SOX10 (22q13.1) Prevalence: <1/106 | Hypopigmentation abnormalities of hair and skin like WS1 | Facial dysmorphism: like WS1 Eyes: like WS1 Neurological signs: SNHL, Hirschsprung disease Neurologic Waardenburg-Shah syndrome or PCWH (Peripheral demyelinating neuropathy, central dysmyelinating leukodystrophy, Waardenburg syndrome and Hirschsprung disease). Association of the features of WS4 and neurological impairment (neonatal hypotonia, intellectual deficit, nystagmus, progressive spasticity, ataxia, and epilepsy) | |

| Tietz syndrome | TS AD dominant negative effect Gene MITF (3p14-p13) | Extremely rare (only few families described) | Generalized uniform hypopigmentation of the skin (100%): the affected patients are born “snow white”, then they gradually gain some pigmentation (fair skin) and they may have reddish freckles Hair, eyebrows and eyelashes (100%): blonde to white | Facial dysmorphism: not present Neurological signs: severe congenital bilateral SNHL (100%) Eyes: blue eyes and hypopigmented fundi |

| Piebaldism | PBT AD Genes KIT (4q12) SNAI2 (8q11.21) | Incidence <1:20,000 | Congenital well-demarked, symmetrical, non-pigmented patches involving the skin of the face, trunk, arms and legs. The skin lesions are usually stable during life, although hyperpigmented dots or macules may appear within or at their margins Café-au-lait macules can be present (co-occurrence with neurofibromatosis type 1). Poliosis is traditionally known as “white forelock” (localized patch of white hair in a group of hair follicles). It is often triangular and may be the only manifestation of PBT in 80–90% of c-Kit carriers. Leukotrichia of eyebrows and eyelashes | Heterochromia irides, neurological impairment and SNHL occur rarely. Spritz et al. described a South African female affected by severe SNHL and PBT, carrying a heterozygous missense change (p.R796G) in the KIT gene [12] Human homozygosity for the KIT germline mutations has been reported in a severe multisystem phenotype consisting of hypopigmented skin and hair, blue irides, neurodevelopmental delay, hypotonia, SNHL, anemia, brachycephaly, and clinodactyly [13,14] |

| OculocutaneousAlbinism OCA | OCA is a heterogeneous and autosomal recessive disorder | NOTE: All types of OCA are associated with increased risk of precancerous skin lesions and skin tumors (non-melanoma and melanoma skin cancers) | NOTE: Congenital SNHL has been described in a few OCA patients as a consequence of the co-occurrence of AR deafness and OCA | |

| OCA1A, OCA1B AR Gene TYR (11q14.3) | The most common subtype in Caucasians, accounting for about 50% of cases worldwide Incidence 1:20,000/40,000 births | Generalized congenital hypopigmentation of the skin (white or very light) White or nearly white or light yellow/blonde hair, eyebrows and eyelashes | Ocular signs: nystagmus; reduced iris pigment with iris translucency; reduced retinal pigment with visualization of the choroidal blood vessels on ophthalmoscopic examination; foveal hypoplasia with reduction in visual acuity, strabismus, blue irides that darken to green/hazel or light brown/tan with age | |

| OCA2, AR Gene OCA2 (15q12) | The most common OCA type in Africa accounting for 30% of cases worldwide Incidence 1:20,000/40.000 births | Generalized congenital hypopigmentation of the skin (never white but range from very fair to near normal). The skin color may darken over time and sun exposure Lightly pigmented hair, eyebrows and eyelashes (never white but range from light yellow to blonde to brown), the hair color may darken with age | Ocular signs: like OCA1 with visual acuity usually better than OCA1 Iris color: it ranges from blue to brown | |

| OCA3, AR Gene TYRP1 (9p23) | Prevalence: 1/8.500 individuals in African population It is extremely rare in Caucasian population | Generalized light or freckled or light brown skin Ginger-red or blonde hair | Ocular signs: like OCA1 Iris color: blue or brown | |

| OCA4, AR Gene SLC45A2 (5p13.3) OCA6, AR SLC24A2 (9p22.1) OCA5, AR Gene unknown (4q24) OCA7, AR Gene C10ORF11 (10q22.2) | Extremely rare | Generalized congenital hypopigmentation of the skin (never white, range from creamy white to near normal) Lightly pigmented hair, eyebrows and eyelashes (never white but range from silvery to golden or near normal) The hair color may darken with age. | Ocular signs: like OCA1 with visual acuity usually better than OCA1. OCA6 and 7 patients do not present an obvious change in the pigmentation patterns. Iris color: it ranges from blue to brown | |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gironi, L.C.; Colombo, E.; Brusco, A.; Grosso, E.; Naretto, V.G.; Guala, A.; Di Gregorio, E.; Zonta, A.; Zottarelli, F.; Pasini, B.; et al. Congenital Sensorineural Hearing Loss and Inborn Pigmentary Disorders: First Report of Multilocus Syndrome in Piebaldism. Medicina 2019, 55, 345. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55070345

Gironi LC, Colombo E, Brusco A, Grosso E, Naretto VG, Guala A, Di Gregorio E, Zonta A, Zottarelli F, Pasini B, et al. Congenital Sensorineural Hearing Loss and Inborn Pigmentary Disorders: First Report of Multilocus Syndrome in Piebaldism. Medicina. 2019; 55(7):345. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55070345

Chicago/Turabian StyleGironi, Laura Cristina, Enrico Colombo, Alfredo Brusco, Enrico Grosso, Valeria Giorgia Naretto, Andrea Guala, Eleonora Di Gregorio, Andrea Zonta, Francesca Zottarelli, Barbara Pasini, and et al. 2019. "Congenital Sensorineural Hearing Loss and Inborn Pigmentary Disorders: First Report of Multilocus Syndrome in Piebaldism" Medicina 55, no. 7: 345. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55070345

APA StyleGironi, L. C., Colombo, E., Brusco, A., Grosso, E., Naretto, V. G., Guala, A., Di Gregorio, E., Zonta, A., Zottarelli, F., Pasini, B., & Savoia, P. (2019). Congenital Sensorineural Hearing Loss and Inborn Pigmentary Disorders: First Report of Multilocus Syndrome in Piebaldism. Medicina, 55(7), 345. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55070345