The Effect of Long-Term Second-Generation Antipsychotics Use on the Metabolic Syndrome Parameters in Jordanian Population

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Data Collection and Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the third report of the national cholesterol education program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel III). JAMA 2001, 285, 2486–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, V.; Parikh, R.M.; Parikh, R.; Parikh, R.M. Changing definitions of metabolic syndrome. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 16, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- International Diabetes Federation. The IDF consensus worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome. IDF Commun. 2006, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sherling, D.H.; Perumareddi, P.; Hennekens, C.H. Metabolic syndrome: Clinical and policy implications of the new silent killer. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 22, 365–367. [Google Scholar]

- Oda, E. Metabolic syndrome: Its history, mechanisms, and limitations. Acta Diabetol. 2012, 49, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samson, S.L.; Garber, A.J. Metabolic syndrome. Endocrin. Metabol. Clinics 2014, 43, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltrán-Sánchez, H.; Harhay, M.O.; Harhay, M.M.; McElligott, S. Prevalence and trends of Metabolic Syndrome in the adult US population, 1999–2010. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, R. Metabolic syndrome: Is it a syndrome? does it matter? Circulation 2007, 115, 1806–1810; discussion 1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newcomer, J.W. Second-Generation (Atypical) Antipsychotics and Metabolic Effects. CNS Drugs 2005, 19, 1–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S. Excess mortality of schizophrenia. A meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 1997, 171, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riordan, H.J.; Antonini, P.; Murphy, M.F. Atypical Antipsychotics and Metabolic Syndrome in Patients with Schizophrenia: Risk Factors, Monitoring, and Healthcare Implications. Am. Heal. Drug Benefits 2011, 4, 292–302. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, T.J.; Furberg, C.D. The harms of antipsychotic drugs: Evidence from key studies. Drug Safety 2017, 40, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Hert, M.; Dobbelaere, M.; Sheridan, E.; Cohen, D.; Correll, C. Metabolic and endocrine adverse effects of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents: A systematic review of randomized, placebo controlled trials and guidelines for clinical practice. Europ. Psy. 2011, 26, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez Rodriguez, A.; Tajima-Pozo, K.; Lewczuk, A.; Montañes-Rada, F. Atypical antipsychotics and metabolic syndrome. Cardiovasc. Endocrinol. 2015, 4, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haupt, D.W. Differential metabolic effects of antipsychotic treatments. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006, 16, S149–S155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coccurello, R.; Moles, A. Potential mechanisms of atypical antipsychotic-induced metabolic derangement: Clues for understanding obesity and novel drug design. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 127, 210–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasnain, M.; Vieweg, W.V.R. Acute Effects of Newer Antipsychotic Drugs on Glucose Metabolism. Am. J. Med. 2008, 121, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, H.; Cohen, D.; Scheffer, H.; Gispen-de Wied, C.; Arends, J.; Wilmink, F.W.; Franke, B.; Egberts, A.C. HTR2C gene polymorphisms and the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: A replication study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2009, 29, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Winkel, R.; Moons, T.; Peerbooms, O.; Rutten, B.; Peuskens, J.; Claes, S.; van Os, J.; De Hert, M. MTHFR genotype and differential evolution of metabolic parameters after initiation of a second generation antipsychotic: An observational study. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2010, 25, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, A.M.; Ngai, Y.F.; Ronsley, R.; Panagiotopoulos, C. Cardiometabolic risk and the MTHFR C677T variant in children treated with second-generation antipsychotics. Transl. Psychiatry 2012, 2, e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrallah, H. Atypical antipsychotic-induced metabolic side effects: Insights from receptor-binding profiles. Mol. Psychiatry 2008, 13, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, C.E.; Lieberman, J.A.; Stroup, T.S.; McEvoy, J.P.; Swartz, M.S.; Rosenheck, R.A.; Perkins, D.O.; Keefe, R.S.; Davis, S.M.; Lebowitz, B.D.; et al. Effectiveness of Antipsychotic Drugs in Patients with Chronic Schizophrenia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 1209–1223. [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, North American Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 596–601. [Google Scholar]

- Obeidat, A.A.; Ahmad, M.N.; Haddad, F.H.; Azzeh, F.S. Alarming high prevalence of metabolic syndrome among Jordanian adults. Pak. J. Med Sci. 2015, 31, 1377–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasein, N.; Ahmad, M.; Matrook, F.; Nasir, L.; Froelicher, E. Metabolic syndrome in patients with hypertension attending a family practice clinic in Jordan. East. Mediterr. Heal. J. 2010, 16, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.C.; Farin, H.M.F.; Abbasi, F.; Reaven, G.M. Comparison of Waist Circumference Versus Body Mass Index in Diagnosing Metabolic Syndrome and Identifying Apparently Healthy Subjects at Increased Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 2008, 102, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications: Report of a WHO consultation.part 1, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/66040 (accessed on 19 January 2019).

- RxList. Schizophrenia. Available online: https://www.rxlist.com/schizophrenia/article.htm (accessed on 27 June 2019).

- Zeier, K.; Connell, R.; Resch, W.; Thomas, C.J. Recommendations for lab monitoring of atypical antipsychotics. Curr. Psychiatr. 2013, 12, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Huang, X.-F.; Shao, R.; Chen, C.; Deng, C. Molecular Mechanisms of Antipsychotic Drug-Induced Diabetes. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weston-Green, K.; Huang, X.-F.; Deng, C. Second Generation Antipsychotic-Induced Type 2 Diabetes: A Role for the Muscarinic M3 Receptor. CNS Drugs 2013, 27, 1069–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.E.; Yamazaki, H.; Ward, K.M.; Schmidt, A.W.; Lebel, W.S.; Treadway, J.L.; Gibbs, E.M.; Zawalich, W.S.; Rollema, H. Inhibitory Effects of Antipsychotics on Carbachol-Enhanced Insulin Secretion From Perifused Rat Islets: Role of Muscarinic Antagonism in Antipsychotic-Induced Diabetes and Hyperglycemia. Diabetes 2005, 54, 1552–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engl, J.; Laimer, M.; Niederwanger, A.; Kranebitter, M.; Starzinger, M.; Pedrini, M.T.; Fleischhacker, W.W.; Patsch, J.R.; Ebenbichler, C.F. Olanzapine impairs glycogen synthesis and insulin signaling in L6 skeletal muscle cells. Mol. Psychiatry 2005, 10, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, J.R.; Svensson, C.K.; Vedtofte, L.; Jakobsen, M.L.; Jespersen, H.S.; Jakobsen, M.I.; Koyuncu, K.; Schjerning, O.; Nielsen, J.; Ekstrøm, C.T.; et al. High prevalence of prediabetes and metabolic abnormalities in overweight or obese schizophrenia patients treated with clozapine or olanzapine. CNS Spectr. 2018, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, E.J.; Woolson, S.L.; Hamer, R.M.; Dunlop, B.W. Risk of lipid abnormality with haloperidol, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in a Veterans Affairs population. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2009, 24, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.; Folsom, D.; Sasaki, A.; Mudaliar, S.; Henry, R.; Torres, M.; Golshan, S.; Glorioso, D.K.; Jeste, D. Increased Framingham 10-year risk of coronary heart disease in middle-aged and older patients with psychotic symptoms. Schizophr. Res. 2011, 125, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellavia, A.; Centorrino, F.; Jackson, J.W.; Fitzmaurice, G.; Valeri, L. The role of weight gain in explaining the effects of antipsychotic drugs on positive and negative symptoms: An analysis of the CATIE schizophrenia trial. Schizophr. Res. 2019, 206, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davey, K.J.; Cotter, P.D.; O’Sullivan, O.; Crispie, F.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F.; O’Mahony, S.M.; Cotter, P.; Dinan, T.; Cryan, J. Antipsychotics and the gut microbiome: olanzapine-induced metabolic dysfunction is attenuated by antibiotic administration in the rat. Transl. Psychiatry 2013, 3, e309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetz, R.L.; Miller, B.J. Meta-analysis of ghrelin alterations in schizophrenia: Effects of olanzapine. Schizophr. Res. 2019, 206, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Mao, X.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Z. Pharmacogenetic Correlates of Antipsychotic-Induced Weight Gain in the Chinese Population. Neurosci. Bull. 2019, 35, 561–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikeç, G.; Arabaci, L.B.; Uzunoglu, G.B.; Mizrak, S.D. Metabolic Side Effects in Patients Using Atypical Antipsychotic Medications During Hospitalization. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Heal. Serv. 2018, 56, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, K.A.; Parks, C.G.; Yost, J.P.; Bennett, J.I.; Onwuameze, O.E. Acute Blood Pressure Changes Associated With Antipsychotic Administration to Psychiatric Inpatients. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018, 20, pii: 18m02299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, A.; Rohrich, M.; Newman, W.; Wolf, P. Cardiometabolic management in severe mental illness requiring an atypical antipsychotic. Ment. Heal. Clin. 2018, 7, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackin, P. Cardiac side effects of psychiatric drugs. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2008, 23, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fındıklı, E.; Gökçe, M.; Nacitarhan, V.; Camkurt, M.A.; Fındıklı, H.A.; Kardaş, S.; Şahin, M.C.; Karaaslan, M.F. Arterial Stiffness in Patients Taking Second-generation Antipsychotics. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2016, 14, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puangpetch, A.; Unaharassamee, W.; Jiratjintana, N.; Koomdee, N.; Sukasem, C. Genetic polymorphisms of HTR2C, LEP and LEPR on metabolic syndromes in patients treated with atypical antipsychotic drugs. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2018, 70, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zabala, A.; Bustillo, M.; Querejeta, I.; Alonso, M.; Mentxaka, O.; González-Pinto, A.; Ugarte, A.; Meana, J.J.; Gutiérrez, M.; Segarra, R. A Pilot Study of the Usefulness of a Single Olanzapine Plasma Concentration as an Indicator of Early Drug Effect in a Small Sample of First-Episode Psychosis Patients. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2017, 37, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyde, N.; Dodd, S.; Venugopal, K.; Purdie, C.; Berk, M.; O’Neil, A. Prevalence of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Events in Patients Prescribed Clozapine: A Retrospective Observational, Clinical Cohort Study. Curr. Drug Saf. 2015, 10, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tofthagen, C. Threats to Validity in Retrospective Studies. J. Adv. Pr. Oncol. 2012, 3, 181–183. [Google Scholar]

| Weight Gain | Hypercholesterolemia | Blood Pressure | Hyperglycemia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olanzapine | +++ | +++ | +/− | +++ |

| Clozapine | +++ | +++ | - | +++ |

| Risperidone | ++ | + | - | + |

| Quetiapine | ++ | ++ | - | ++ |

| Aripiprazole | +/0 | +/0 | - | +/0 |

| Ziprasidone* | +/0 | +/0 | - | +/0 |

| Variable | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 47 (51.6%) |

| Female | 44 (48.4%) | |

| Marital Status * | Single | 31 (37.3%) |

| Married | 40 (48.2%) | |

| Divorced/Widowed | 12 (14.5%) | |

| Living Status * | With family/partner | 79 (91.8%) |

| Alone | 7 (8.2%) | |

| Education Level * | Primary education | 18 (22.2%) |

| Secondary education | 20 (24.7%) | |

| Post-secondary education | 43 (53.1%) | |

| Employment Status | Employed | 47.2 (47.2%) |

| Unemployed | 47 (52.8%) | |

| Age mean (SD) | 41.4 (16.13) | |

| Metabolic Syndrome Factor | ATP III Criteria* | Time 1 Mean (SD) | Time 2 Mean (SD) | p Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | ||

| Systolic Blood Pressure | ≥130 mmHg | 121.6 (16.34) | 120.1 (16.62) | 123.2 (16.07) | 125.7 (11.95) | 126.8 (9.70) | 124.5 (13.98) | 0.045 | 0.014 | 0.660 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | ≥85 mmHg | 75.3 (9.66) | 73.6 (9.96) | 77.2 (9.07) | 79.7 (9.63) | 80.3 (10.14) | 79.0 (9.12) | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.268 |

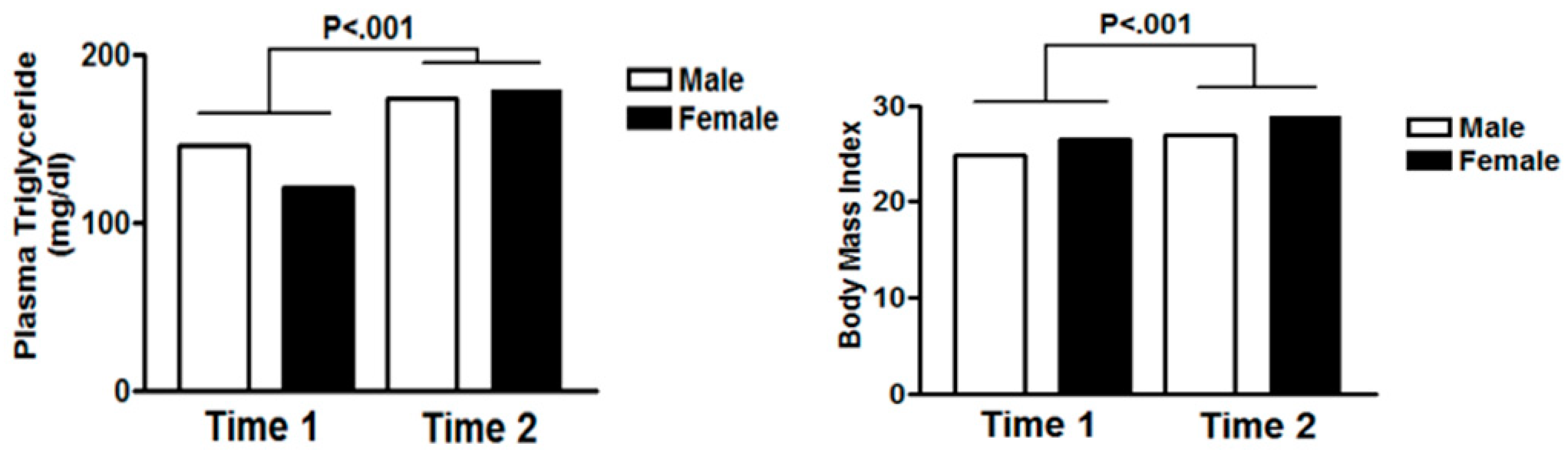

| Triglyceride | ≥150 mg/dL | 133.6 (85.87) | 146.0 (104.77) | 120.49 (57.84) | 176.1 (100.49) | 173.3 (103.91) | 179.1 (97.80) | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| High density lipoproteins (HDL) Cholesterol | <40 mg/dL for men <50 mg/dL for women | 45.9 (21.37) | 45.3 (24.82) | 46.6 (17.18) | 43.4 (13.49) | 42.4 (14.05) | 44.42 (12.93) | 0.274 | 0.280 | 0.280 |

| Fasting Glucose | ≥110 mg/dL | 96.8 (28.16) | 99.6 (35.98) | 93.7 (16.03) | 112.66 (49.79) | 116.9 (62.4) | 108.2 (31.32) | 0.001 | 0.031 | 0.003 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | - | 25.6 (4.38) | 24.8 (3.05) | 26.5 (5.34) | 27.9 (5.88) | 26.9 (3.68) | 28.9 (7.43) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.009 |

| Metabolic Syndrome Factor | ATP III* Criteria for Metabolic Syndrome | Time 1 N (%) | Time 2 N (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

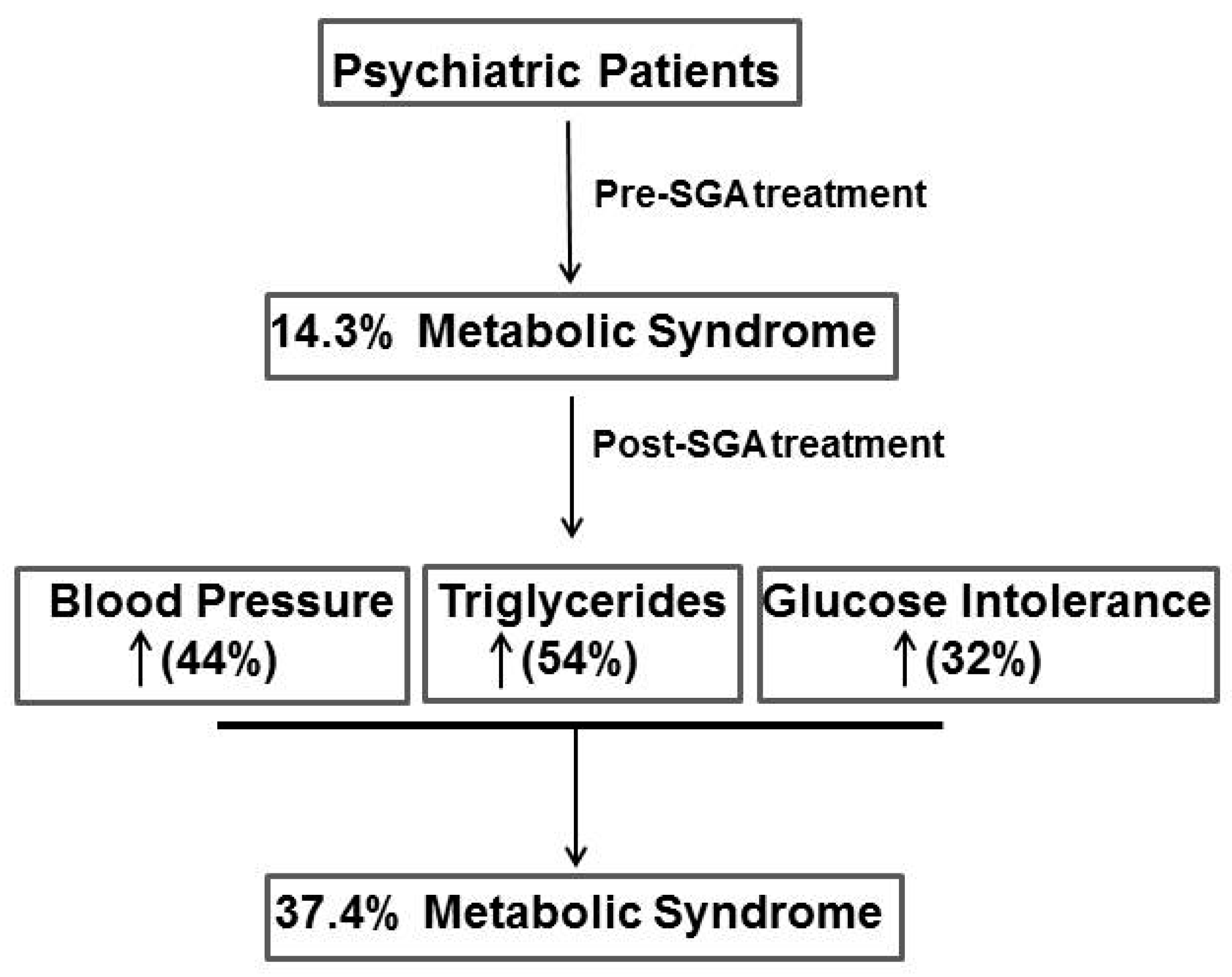

| Systolic Blood Pressure | ≥130 mmHg | 14 (15.4%) | 40 (44.0%) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | ≥85 mmHg | 18 (19.8%) | 26 (28.6%) | 0.113 |

| Triglyceride | ≥150 mg/dL | 23 (25.3%) | 50 (54.9%) | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol | <40 mg/dL for men | 40 (44.0%) | 38 (41.8%) | 0.440 |

| < 50 mg/dL for women | ||||

| Fasting glucose | ≥110 mg/dL | 12 (13.2%) | 29 (31.9%) | <0.001 |

| BMI ≥30kg/m2 | - | 12 (13.3%) | 21 (23.3%) | 0.061 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abo Alrob, O.; Alazzam, S.; Alzoubi, K.; Nusair, M.B.; Amawi, H.; Karasneh, R.; Rababa’h, A.; Nammas, M. The Effect of Long-Term Second-Generation Antipsychotics Use on the Metabolic Syndrome Parameters in Jordanian Population. Medicina 2019, 55, 320. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55070320

Abo Alrob O, Alazzam S, Alzoubi K, Nusair MB, Amawi H, Karasneh R, Rababa’h A, Nammas M. The Effect of Long-Term Second-Generation Antipsychotics Use on the Metabolic Syndrome Parameters in Jordanian Population. Medicina. 2019; 55(7):320. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55070320

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbo Alrob, Osama, Sayer Alazzam, Karem Alzoubi, Mohammad B. Nusair, Haneen Amawi, Reema Karasneh, Abeer Rababa’h, and Mohammad Nammas. 2019. "The Effect of Long-Term Second-Generation Antipsychotics Use on the Metabolic Syndrome Parameters in Jordanian Population" Medicina 55, no. 7: 320. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55070320

APA StyleAbo Alrob, O., Alazzam, S., Alzoubi, K., Nusair, M. B., Amawi, H., Karasneh, R., Rababa’h, A., & Nammas, M. (2019). The Effect of Long-Term Second-Generation Antipsychotics Use on the Metabolic Syndrome Parameters in Jordanian Population. Medicina, 55(7), 320. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55070320