Abstract

As a result of recent political changes in North Macedonia, economic practice in the country has moved away from the communist model that was dominated by state ownership. As a part of this movement, the National Association of Private Forest Owners was founded to support the sustainable management of private forests and as an instrument to help overcome the new challenges faced by this new interest group and government policy in local forestry. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to understand the enabling and constraining aspects of North Macedonian forest policy on the institutionalisation of private forestry. The findings show that some socialist structures and practices related to forest management activities on private forest land still exist. The attempts to strengthen private forestry by introducing more modern forms of institutionalisation can be seen in the country’s Law on Forests amendment from 2011 initiating the denationalisation of forest management activities on private forest land and introducing private licenced bodies for such. With further amendments in 2014, the policy largely returned to how it was when the country was a part of Yugoslavia, influencing the progress of the institutionalisation of private forestry to remain symbolic. Integrating solutions to private forestry problems and concerns into the broader forest policy domain requires a deep understanding of private forestry rational principles and a strong political will to do so. Effective national forest policy coordination is one of the solutions.

1. Introduction

As a result of the political changes in South-Eastern Europe (SEE) that began in the 1990s with the disintegration of Yugoslavia, countries throughout the region have been going through a challenging process of political, social, and economic transition [1], including in forest policy and areas related to private forest management and planning. In 1991, the Republic of North Macedonia, as an independent country, began its move towards a pluralistic system and a market economy, abandoning the communist approach, which extolled the “superiority of socialist forms of ownership” [2], in favour of establishing a private sector and ensuring its freedom to operate and develop. This transformation of the economic system started with the privatisation of big state-owned enterprises and gave the necessary green light for private small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to enter the marketplace [3]. These initial steps were followed by institutional changes facilitating the creation of new favourable policies for private business and stimulating entrepreneurship.

Changes were also introduced that changed the traditional way the forest sector had operated in the post-WW2 era. In former Yugoslav republics and other ex-socialist states throughout Europe, restitution processes have been taking place since the 1990s [4]. After the fall of the communist regimes and with the start of these restitution processes, forest-owners associations began to form and became active in local forestry [5]. In North Macedonia, the restitution of forest land emerged as one of the most important required changes, and its implementation started with the adaptation of the Law on Denationalisation. While efforts in this regard are still ongoing, they appear to be progressing very slowly, and there is a lack of data (area, types, status) about the forests that are subject to the denationalisation process. Some reports, [6] based on experts’ assessments, show that private forest owners (PFOs) will eventually control a maximum of 15% of forests in North Macedonia [6,7]. The restitution and privatisation process requires the active involvement of PFOs and will influence how PFOs act when establishing their various associations [6]. Changes to North Macedonia’s forest sector have already triggered the inclusion of PFOs in national forest policy processes, and since the reforms began, PFOs have been hopeful regarding the privatisation, participation, and transparency aspects of the transition that they wanted to see result in a Western capitalist approach to forestry. However, the success of capitalism within a state is strongly dependent on the development of general national systems of legal enforceability, which very often take a long time to establish [8]. Thus, in 1997, the association of PFOs was established, and 9 years later, the association became the National Association of Private Forest Owners (NAPFO) and deals with private forest issues throughout North Macedonia.

Forest owners’ associations, as an instrument to support the sustainable management of private forests, have emerged as an effective option in overcoming the new challenges represented by restitution processes [9]. The establishment of a private forest sector seemingly opened the door for the inclusion of owners in North Macedonian forest policy processes, however, time and reality have shown that local policy processes have gone down a different path. Some of the owners’ expectations have been realised with regard to legal enforceability (participation in the policy process, subsidies), while others have failed to materialise (independent forest advisory services, liberalisation regarding forest management activities, restitution, and solving issues of fragmentation) [6], thus leaving private forestry stuck in a state of dated institutionalisation with no clear signs that their views are being listened to or that the overall discourse in forest policies will produce a more dynamic approach towards further institutional change.

The State of the Private Forest Sector in North Macedonia

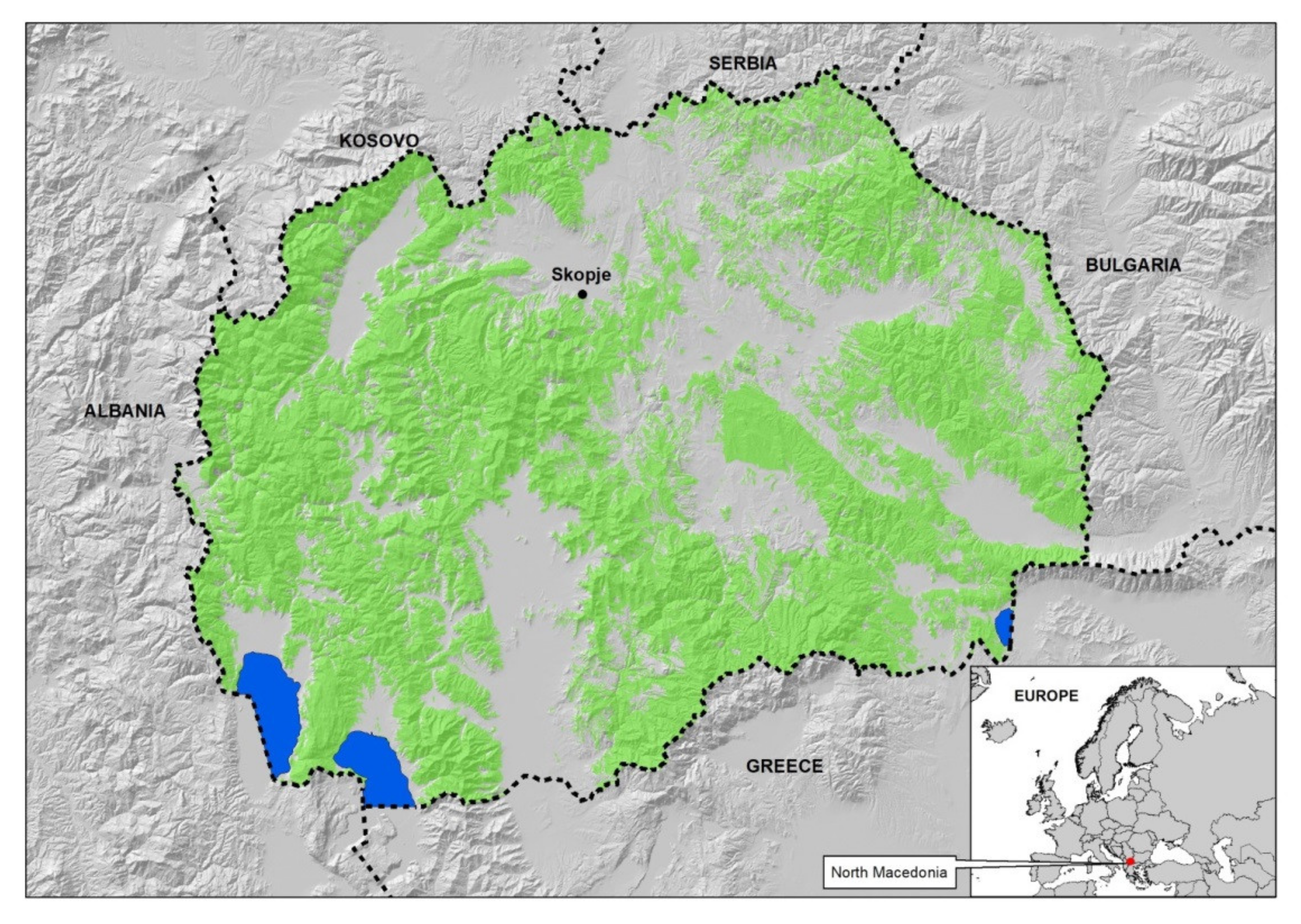

The Republic of North Macedonia is located in the Balkan Peninsula (see Figure 1), covers 25,713 km2 and has a population of 2,022,547 people [10]. The total area classed as forest land is 1,159,600 ha, of which 947,653 ha is actually forested, while the total wood inventory is estimated to be 74,343,000 m3 with a total annual increment of 1,830,000 m3 [9]. Although approximately 45% [10] of the country is classed as forest land, the forestry sector’s contribution to the economy is insignificant [11] as it contributes only 0.5% to GDP.

Figure 1.

Geographical position of North Macedonia.

Article 2 from the Law on Forests (LF) recognises two types of forest ownership structures in North Macedonia, namely private and state-owned. In a report from 2018 by the State Statistical Office, some 90% of the country’s forests are state-owned, while only 10% are privately owned and scattered as individual or group parcels within state forests. These private forests comprise around 220,000 private parcels owned by 65,000 families [9], occupy an area of 94,146 ha, and contain 7.8% of the country’s total wood inventory. This paints a clear image for PFOs of their forests as small and disjointed estates with relatively low wood production that is used mainly to satisfy domestic fuelwood needs [11].

In 1997, the North Macedonian government decided to establish a public enterprise called Makedonski šumi (now Nacionalni šumi) (PENŠ), which is now responsible for the management of 90% of the state forests. The large disparity in scale between publicly and privately owned forests and the domination of PENŠ in the sector, coupled with its continued use of policies inherited from the previous socialist system, has led to private forestry being neglected. Nevertheless, the transition period has seen PFOs succeed in bringing about some changes in forest policy, such as land tenure and the strengthening of private property rights [1,6,12], both of which have provided new opportunities for PFOs. The Cambridge dictionary defines property rights as “the rights of people and companies to own and use land, capital, etc., and to receive a profit from it.” Possession refers to the control of a good or resource [12] and it is to the owner’s benefit to be capable to make more effective utilisation of their forest [6].

The situation regarding forest management (utilisation) on private forest land remains unchanged from the pre-1990 period as it remains under state jurisdiction and control [6]. The creation process of forest management plans as well as the marking of trees and licence permissions for harvesting remain solely under PENŠ jurisdiction, similar to the situation that existed when Yugoslavia still existed. According to the Program on Forest (PROFOR), “forest governance is critical to the sustainable and equitable management of forests and landscapes and to enabling poverty reduction and shared prosperity through thoughtful stewardship and use of forest resources”.

The aim of this study was to analyse the changes in forest policies that are related to forest management activities on private forest land, with a special focus on private licenced bodies. The private licenced bodies were founded by the 2011 amendment to the LF and were responsible for marking and licence permissions for harvesting operations in private forests. As was mentioned above, these services operated for only three years as they were under PENŠ’s jurisdiction prior to 2011 and were abolished and returned to PENŠ by the 2014 amendment. This regression has seriously affected efforts to institutionally reform private forestry in North Macedonia.

Seeking to understand the North Macedonian situation with regard to its institutionalisation of forest management activities on private forest land, this paper responds to the following two research questions:

- RQ 1: How do institutions emerge from and become embedded in forest management practices on private forest land throughout the country?

- RQ 2: How have government policies enabled or constrained the institutionalisation of private forestry?

2. Institutionalism

Theories of new institutionalism are particularly useful in explaining policy change, or lack thereof, since they focus on how and why institutions originate, persist, and evolve, as well as on the process of institutional reproduction and institutionalisation [13]. Different versions of new institutionalism significantly differ in explaining these institutional origins, continuities, and changes. Schmidt [14] considered four types of institutional approaches—rational choice, historical, sociological, and discursive institutionalism, all of which are briefly outlined below.

Rational choice institutionalism (RI) presumes that actors have fixed preferences and act rationally to maximise their preferences, while institutions influence actors to reduce or minimise uncertainty. The RI approach assumes that actors can understand the effects of the institutions created by them and very often rely on the functionalist explanation for the existence of institutions.

Sociological institutionalism (SI) examines how the actors follow rules, assuming that culture and identity are the sources of the actors’ interests. SI emphasises how institutions shape actors rather than how actors shape institutions.

Historical institutionalism (HI) conceives institutions as being sets of regularised practices. The main focus of HI is on comparing institutions and their development over time.

Discursive institutionalism (DI) examines how actors generate and legitimise ideas through the logic of communication, focusing on the interactive and participative process in which ideas are generated.

Although Schmidt [14] argues that these four types of institutionalism should be considered complementary to each other rather than different ways of understanding the same change or phenomena in practice, this is not the case and scholars have usually only used one or two types of institutionalism to explain various phenomena. Within this paper, the complementarity of rational choice, historical and discursive institutionalism is considered.

The basic point of analytical departure in HI are choices that are made early in the history of any policy, or indeed, of any governmental system. These initial policy choices, and the institutionalised commitments that grow out of them, are debated to determine subsequent decisions. If we do not understand these initial decisions in the development of a policy, it then becomes difficult to understand the logic behind its development. This is one of the starting points of this paper, an examination of the North Macedonian situation regarding private licenced bodies before 2011, from 2011 to 2014 and, finally, in the years following the second amendment in 2014. The political institutions, that is the structures, processes, practices, rules, and cultural norms of governance [15], play a significant role in structuring political action [16,17,18]. History has shown us that generally, political institutions are difficult to change, and when they do change, there is a path dependency based on that change [19].

Policies, irrespective of the area they seek to regulate, are normally path-dependent and once launched on a path, they continue along it until some sufficiently strong political force deflects them from it [20]. For HI, path dependency is the main factor for explaining both incremental changes and how inherited institutional contexts influence policy development and determine so-called trajectories [21,22,23]. The institutions are considered as relatively persistent and, therefore, embrace institutional change through gradual adaptation, making greater changes as they proceed further down the path using positive feedback. Adhering to path dependency is an approach that clearly serves actors” interests since changing to a new path can be costly [23]. Hence, creating new institutions is more difficult than changing the old ones or “de-institutionalising” a process or area of activity [24]. This is how institutional structures influence power relations between actors and, therefore, HI considers that institutions influence not only the actor but also the interactions between the actors, where power inequalities serve to then influence the trajectories of institutional developments [22,25,26].

From an HI perspective, an actor’s behaviour is determined by institutions, which influence the actor’s choices as well as its interpretations and views of the environment in which it operates. Turning to North Macedonia specifically, it is important to also understand how institutions have changed in an attempt to break away from the old socialist system and create market-oriented and democratic systems. This break from the past and these overarching goals for the future can also influence actors’ behaviour and power relation between them. Johnson [27] considers this change is defined by its reuse of old institutions to serve new ends, namely their evolution into market-oriented institutions and their redirection to act as links between state and society rather than as instruments to dictate to society. In this paper, the HI explanatory potential, as summarised in the concept of path dependence, will assist in understanding the effects of past institutions prior to the disintegration of Yugoslavia and the situation afterwards, focusing on how institutions develop and adapt rather than on how they function [28].

The RI approach considers that actors behave entirely rationally and in a strategic way to maximise the attainment of what they perceive to be in their best interest [22]. Institutions can be seen as utilising rules as a means to prescribe, proscribe, and permit behaviour [29] but where such rules can be also considered [30] as guides for society and humanly devised constraints that shape human interactions. Compliance is one of the major concerns of RI theory. The problem of compliance can also be conceptualised as a set of interactions played out between one group of actors (usually legislators) attempting to ensure the compliance of other groups’ actors (usually bureaucrats), while the latter generally seek greater latitude for action [31]. This means that bureaucrats should not be viewed negatively but only as self-interested and naturally pursuing their individual and group vision of public interest in their respective policy areas [32]. In order to undertake a deeper institutional analysis, the first goal of this study is to understand the rules that actors use in making decisions for forest management activities on private forest land. Once these rules are understood, the next logical step is to understand where those rules come from. In a system governed by the rule of law, the general legal framework in use will have its source in actions taken in constitutional, legislative, and administrative settings augmented by decisions taken by individuals in many different and decidedly specific settings [33]. In other words, the rules-in-form are consistent with the rules-in-use [34].

DI, as another type of institutional theory, emphasises the constitutive role of ideas and discourses in politics, policymaking, and institutional change [22,35,36]. The DI approach is primarily advanced by Vivien Schmidt [22,36,37]. The basic principle is that new ideas and the discourses through which institutions are created or changed are presented during policymaking processes and public deliberation. Such exchanges create the opportunity to decide upon reinforcing existing institutions, causing institutional change or opting for maintaining the status quo [22,38]. The DI approach is a suitable analytical framework to conceptualise how the concept of the de-bureaucratisation of forest management activities on private forest land, as well as a number of associated ideas, have shaped and been institutionalised in the relevant national institutional arrangements in North Macedonia. As an analytical framework, DI distinguishes between the discourses and institutions [38] and can be considered an attempt to bridge discourse and institutional theories [39]. This double conceptualisation of discourse enables us to “simultaneously indicate the ideas represented in the discourse and the interactive processes by which ideas are conveyed” ([22], p. 309) during policymaking and public deliberations involving discussions between the various policy-relevant actors. For this paper’s purposes, this coordinative discourse comprises the individuals (experts) involved in the generation, exchange, elaboration, and development of forest policy ideas. The main aim of this stakeholder involvement is coordinating agreement among themselves on the best policies to achieve an appropriate solution for forest management practices on private forest land throughout the country.

3. Materials and Methods

Over the years, research about issues related to private forest owners and forest ownership structures has been conducted to see how certain institutions have changed the institutional environment of private forestry. Many scholars have investigated the typology of forest owners as well as other changes related to private forestry. The growing focus on studying private forestry issues in recent years is particularly apparent in former socialist countries as a result of restitution processes, but this trend extends to other parts of Europe and is related to issues concerning new types of forest owners, fragmentation of ownership and questions related to the steady supply of forest products to industry [40]. Indeed, many of the specifics of the above are comprehensively elaborated in the joint FAO/UNECE report Who owns our forest—Forest ownership in the ECE region.

This latter study of forest ownership structures particularly helped in the design of the case study used here to consider the institutionalisation of private forest activities in North Macedonia. Changes in private forestry can indeed cover a wide variety of phenomena, including ownership structures, fragmentation, new forest owner types, management activities, and so forth. Within this paper, the case study design applied two steps for reaching the defined objectives—(a) the selection of a specific type of changes (forest management practices on private forest land) and (b) an elaboration of the role these changes have on the institutionalisation of private forestry in North Macedonia.

For all the research activities undertaken within this study, a qualitative content analysis of the relevant policies and collected data was applied. To begin with, three categories for data collection sources were settled upon, namely document analysis, semi-structured interviews with stakeholders, and a stakeholder survey with closed questions. Qualitative data analysis was conducted in a systematic process regarding these sources, starting with the analysis of the relevant policy documents (the LF and both of its amendments, forest strategy, rulebooks, bylaws, and other relevant literature related to private forest owners and state-generated statistical reports). From this source material, the analysis continued by obtaining and arranging interview transcripts, observation notes collected during the conducted interviews, and survey stakeholder data obtained using closed questions and other materials (newspaper articles), all of which illuminated [41] the institutionalisation situation for private forestry in North Macedonia.

A content document analysis was applied to the LF and its amendments as well as other policy documents (PENŠ annual programmes, state statistical reports, the rulebook for the creation of forest management plans, the National Strategy for Sustainable Development of Forestry in the Republic of North Macedonia (NSSDF) and previous versions of the LF from 1974 and 1997). Starting with the general picture of how private forestry is regulated and integrated into the LF, what are the roles of PFOs in the creation of forest management planning, harvesting operation, silviculture measures, and so forth. The main focus of the content document analysis is set on the LF (2009) and its amendments from 2011, 2013, and 2014 (directly related to forest practices on private forest land, licenced bodies and PENŠ). The purpose of the content document analysis was to understand the institutional setup and functionality of forest management activities on private forest land and how they have changed over time.

The selection of the interviewees was done after considering all of the relevant stakeholders related to the institutionalisation of private forest owners in North Macedonia. The first step entailed the identification of the important relevant related actors and securing the cooperation of participants (one per actor), a process that followed a similar pattern to that employed by some studies in transaction-cost literature that divide the process into three steps [42]—(1) defining the population of interest, (2) deciding on the sample size, and (3) selecting a sampling strategy. The population of interest here is a set of all people who are eligible to be interviewed for the goal of understanding North Macedonia’s institutionalisation of private forest ownership. When defining the population of interest, either inclusion (i.e., those with a specific characteristic) or exclusion (i.e., those that do not have the specific characteristic) criteria were used. Deciding on the size of the sample of participants was driven largely by the applied method used in this paper, namely qualitative. The Guest (2006) [43] approach for data saturation was used for defining the sample size for this research. The initial list of the potential interviewees was drafted to have a balanced representation (public vs. private) of identified actors as well as to reach data saturation. All the individuals contacted agreed to be part of this research and most of them had previously been involved in certain forest policy processes. The semi-structured interviews were recorded and transcribed when possible, although some interviewees declined to be recorded and notes were taken instead. These were then transferred into a text document for further processing. In total, eight participants were involved in semi-structured interviews (2 PFOs, 2 (former) managers (owners) of registered licenced bodies, 1 expert (professor) from Hans Em Faculty of Forest Sciences, Landscape Architecture and Environmental Engineering dealing with private forestry issues, 1 consultant (from NGO sector) dealing with private forestry issues, 1 participant from PENŠ, and 1 participant from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Water Economy (MAFWE) from the Forestry and Hunting Department). The list of interviewed persons as well as duration of the interviews can be found in Appendix A. By using semi-structured interviews, the goal was to analyse one complex process, namely policy analysis, to obtain reliable information before delivering conclusions.

To obtain reliable, unbiased information and data, participants in such processes are offered the opportunity to remain anonymous, as was the case in the present research, and as will be adhered to even after publishing this paper. This agreement was to prevent the authority, persona, or reputation of the participant from being a factor in the process. In some cases, anonymity can release the participant to a certain extent from anxiety regarding expressing their personal biases, thus allowing a freer expression of opinions while encouraging and stimulating open critiques and critical thinking. Furthermore, anonymity can also facilitate admissions of mistakes and bring to light instances when previous judgments were revised or reversed. However, of greater importance than its value in contributing to the results, this research considers the confidentiality that comes with anonymity as essential “for sensitive and/or personal information, protecting the privacy of respondents (which) is of utmost concern to researchers [44,45]”.

To get details and narratives around how private forestry is institutionalised and forest management on private forest land is regulated, a single semi-structured interview was developed. The semi-structured interviews with stakeholders were organised as in-person interviews conducted separately with each stakeholder and consisted of five open questions. The interviews started by asking general questions and enquiring after stakeholders’ opinions about private forestry and PFO rights before asking about the changes in the relevant policies related to forest management on private forest land and what the role of the actors was within these processes. Furthermore, the interviews continued with concrete questions related to forest management practices on private forest land, how private forestry is organised, specifics of policy processes, forest governance, and governance principles, such as transparency and participation.

The aim of the semi-structured interviews was to provide a better understanding of the current situation and to provide a body of material that could be compared with the findings from the content document analysis. The interview findings indicate the existence of a certain path dependency, that an actors’ coalition and network had been established, and that lobbying was present within the forest sector. In order to verify and increase the robustness of these results, the third method of data collection was employed, which entailed a survey comprising closed questions. Based on the analysed interviews, as well as the content analysis and theory, a new additional field check (survey) was needed. The new method was applied to fill in some ambiguities that remained unanswered with the interviews and which needed further clarification and confirmation. The analysed and processed interview data were incorporated and presented as statements in the survey (Appendix C) that comprised 21 such statements and given to the same stakeholders for evaluation. The questions from the semi-structured interviews and survey are presented in Appendix B and Appendix C, respectively. The semi-structured interviews were conducted from October 2017 to March 2018, while the survey was undertaken from February to May 2019. The survey was given to the same participants that sat for the interviews, however, it has to be noted that one of the participants had a change of employment and organisation and, therefore, the survey was conducted using only seven of the eight stakeholders.

4. Results

4.1. Institutionalisation of Private Forestry in North Macedonia

The recent forest legislation history of North Macedonia, a former socialist country, comprises three key laws which were passed in 1974 [46], 1997, [47], and 2009, [48] (still in force). The passing, repealing and subsequent updating of these laws reflect the process of institutional adaptation of the country’s forestry sector as it transitioned from the old socialist planned economy to a market economy [12].

Regarding the history of North Macedonian forests and their ownership structure, documents from the Ottoman Empire can be found in the archives, however, very little data for the period from 1903 until WWII were recorded. After WWII, a large portion of private land, including parcels of forest, was nationalised as socialist cooperatives were established in the 1950s, meaning private forest owners lost their management rights. Losing these rights impacted the affected families and forced many to change their way of life, losing interest in forest management and the principles of traditional forestry.

In 1991, North Macedonia proclaimed its independence, which inevitably led to having to address issues on land ownership rights. The restitution process began with the establishment of the Constitution and Restitution Law [49], however, the results from this process did not produce the expected results. The process of denationalisation was complicated by the fact that the initial seizures of private land were not properly documented. Therefore, the restitution process has had difficulties identifying the original owners and land boundaries, meaning many cases have remained stuck mid-process. In 2008, attempts to restore forest land to its original owners or their heirs stopped and has not resumed since. The failure of the restitution process is primarily due to the scale of the complex and bureaucratic process that was used to resolve the numerous property-related issues that have been created in the almost seven decades since the confiscations and restrictions of property rights were forced on owners by the socialist regime [50]. There are expectations that activities in this area will resume, and realistic estimations indicate that there will be an additional 2–3% increase in forest land transferred to private ownership [51].

Redressing what are now seen as the injustices imposed by the old socialist system regarding private property rights and forest management activities [7] resulted, in 1997, in a group of enthusiastic PFOs in Berovo establishing the Association of Private Forest Owners, following a similar trend that occurred in neighbouring countries such as Serbia and Bulgaria. Offering training on how to protect PFO property rights and interests, as well as sustainable forest management practices, were among the association’s first activities [7]. Almost ten years later, in 2006, after the association strengthened its capacities and became more active throughout the entire country, it became the National Association of Private Forest Owners (NAPFO), boasting some 1600 members with its head office located in Berovo and five regional branches scattered across the country. Nowadays, the NAPFO is a serious and well-organised forestry-sector actor with the mission of representing, lobbying, and improving the rights and interests of PFOs in all of North Macedonia [6].

In the national forest policy arena, one of the most significant achievements to date has been the National Strategy for the Sustainable Development of Forestry (the Strategy), which came into being in 2006. The Strategy provides the framework within which all major decisions concerning forestry for the next 20 years will be made. The Strategy’s focus regarding forests is mainly related to their use in producing resources and material goods, such as timber and non-wood forest products (herbs, mushrooms, berries, game, and so forth). Few aspects of the Strategy are directly focused on private forests, however, PFOs considered it a good basis to further develop the NAPFO and private forestry [7]. In 2009, the NAPFO participated for the first time in a forest policy process when the new LF was being drafted. Previous NAPFOs’ activities regarding the needs and problems that PFOs are facing helped in making detailed proposals regarding private forestry issues, which were then integrated into the draft version of the LF [6].

4.2. Law on Forests (2009) and Forest Management Practices on Private Forest Land in North Macedonia

In the FAO Forest Resource Assessment Report (FRA), forest ownership is defined as “generally refers to the legal right to freely and exclusively use, control, transfer, or otherwise benefit from a forest. Ownership can be acquired through transfers such as sales, donations, and inheritance” [52]. The same report also defines the following two types of ownership structures:

- (a)

- Public: “Forest owned by the State; or administrative units of the Public Administration; or by institutions or corporations owned by the public administration.”

- (b)

- Private: “Forest owned by individuals, families, communities, corporations and other business entities, private religious and educational institutions, pension or investment funds, NGOs, nature conservation associations and other private institutions.”

Historically, the definition and understanding of ownership structure have undergone certain changes in North Macedonia as the governing regimes and laws have changed over time. The state was the prevailing actor under the policies of the old socialist regime, however, Article 7 of the LF (2009) recognises that the country’s “forests are privately and State-owned”.

Based on the FRA report [52], “forest management is a system of measures to protect, maintain, establish and tend forest; ensure the provision of goods and services; protect the forest against fire, pest, and diseases; regulate forest production; check the use of forest resources, and monitor forests; as well as to plan, organise and carry out the above-mentioned measures”.

In North Macedonia, state and private forests are equally obliged to have management plans that are made exclusively by the Department for Forest Management Planning operating within the PENŠ. Since 1997, PFOs with forests of over 100 ha are required to produce their own management plan developed by qualified staff, however, given their lack of knowledge and the difficulties in securing the services of qualified staff, many PFOs have not been able to do so. The others private forests with less than 100 ha (around 98% of the PFOs are in this category) are integrated within the state forest management plans.

Forest management practices on private forest land, such as tree marking, issuing licences for cutting, and transporting forest products, were, until 1998, carried out by the MAFWE. In the period from 1998 to 2011, these services were fulfilled by the PENŠ, which was simultaneously responsible for the creation of forest management plans for private forests with an area of less than 100 ha and also acted as a service provider organisation for forest management practices on private forest land. With the introduction of the LF (2009), these management practices on private forest land remained under the auspices of the PENŠ but the influence of PFOs and pressure from NAPFO regarding such issues have increased. The NAPFOs’ active involvement has resulted in the submission of several suggestions to improve the LF, which has been amended 17 times since coming into force. The key amendments to date related to private forestry were made in 2011, 2013, and 2014 and are presented chronically by year and articles in Table 1. These amendments are of vital importance in the context of this paper and help with the explanation and understanding of how and why institutions are being embedded in forest management practices. Understanding the factors, actors, and other forces at work here that create the path dependence and/or pressure to change or readapt institutions to meet particular needs, such as forest management practices on private forest land, lies at the heart of the present research.

Table 1.

Amendments to the LF (2009) related to management practices on private forest land.

The LF (2009) has a chapter entitled “Private-forest management” in which the issues related to forest management practices on private forest land are defined and where Article 97 appears to be the most relevant for forest management practices on private forest land. The first version of Article 97 was introduced in 2009 and stated that “The expert works (forest management activities) within forests under private ownership (private forest land) will be carried out by PENŠ and other entities in charge of managing protected areas”. This regulation is a historical continuation of the socialist approach that entrenched state dominance in the sector. Raising concerns about this arrangement, the NAPFO has highlighted the conflict of interest that arises because PENŠ acts as both the management organisation and service provider for private forests. This was the primary concern that prompted the NAPFO to submit a suggestion to improve Article 97 and, in 2011, another amendment of the LF saw Article 97-a added. For the first time, responsibility for management activities on private forest land was assigned to a number of micro-companies that were designated as private licenced bodies. The MAFWE was the relevant institution for issuing the licences to these bodies whose primary function was conducting management activities on private forest land and forest advisory services. At the beginning of 2011, only a few entrepreneurs recognised this opportunity and only six private licenced bodies were registered, although that number increased to 35 by 2013. This situation was in force until 2014 when the LF amendment passed that year returned all control of management activities on private forest land to PENŠ.

4.3. Policy Process

Over the last two decades, European forest policy has been complicated by changing circumstances involving forest ownership as a result of changes in the lifestyles, attitudes, and behaviour of forest owners, forest restitution processes in Eastern Europe, support for afforestation, and incidences of new forms of ownership [40] (e.g., business entities, religious and educational institutions, urban vs. rural private forest owners).

Often property-rights arrangements are used to define the relationships and roles of the private forest owners, forest managers, and forest authorities [53]. Stable property rights are an important prerequisite for enhancing entrepreneurship in the forest sector [54], increasing the adaptive capacity required to respond to natural disturbances [55], and implementing successful payment schemes designed to promote forest conservation [56].

Usually, the characteristics associated with property rights are initially created by formal and informal institutions that generate spoken or unspoken “rules of the game”. These customary rules are, in turn, transposed and codified in national or sub-national regulatory frameworks that have an impact on the property in question. The resultant formal property rights contextualise what, in this case, a forest owner, manager or resource user, can do with respect to a forest holding and related forest ecosystem services.

Property rights, inheritance laws, restitution, and forest management and planning, as well as governance principles, are some of the main factors that can affect the institutionalisation of private forestry [4,12]. Forest ownership is usually characterised as a system of interrelated but distinct features, which includes the institutional setting, the allocation of property rights, the nature of ownership, the character of the owning entity along with the regulations and organisation of forest management [57]. In all these aspects of ownership, the state has a role in conferring either a stronger or weaker public or private character through tools such as regulatory regimes or the allocation of jurisdictional powers through which it is possible to trace the path followed by the process institutionalising private forestry. The aspects of governance principles, especially participation and transparency, forest management practices on private forest land, such as forest management planning and liberation vs. bureaucratisation, coupled with the role of the actors or coalitions thereof are considered in this paper. The content analysis of the main forest policy documents provided the legal background, while the semi-structured interviews and surveys with closed questions were applied to understand the preceding aspects.

The NAPFO’s participation in the process was that the revised LF must be widely perceived as reasonable, appropriate, and fair [11]. Path dependency is a concept used by institutionalists to explain that the options for correcting bigger developments (those causing de-institutionalisation) are limited and is not in actors’ interests [23]. Hence, creating new institutions (de-institutionalising the old ones) is more difficult than changing the old ones [24]. In formerly socialist countries, the need to create new institutions is self-evident, and the difficulty of creating a new institution is often the better option than attempting to change the old one. Although this need was apparent and seemingly accepted in the years after the dissolution of Yugoslavia, in practice, the old socialist institutions have persisted in many areas of the public sector and simply been re-branded and presented as new entities [58], which has been the case with forest management activities on private forest land in North Macedonia. Based on the interview data and content analysis, the four years from 2009 to 2013 are considered a brief period of both liberalisation and heightened productivity for private forest owners and the NAPFO, especially given the latter’s participation in the drafting process of the 2009 LF. The NAPFO’s active role helped to bring about significant change regarding forest management activities on private forest land through the 2011 amendment to the LF. Looking at this amendment from an institutionalist’s perspective, it is a good example of creating a new institution, namely the registered private licenced bodies, entities that did not exist previously and that saw responsibility pass from the state into private hands.

During the interviews with the private forest owners, the amendment from 2011 was considered a liberalising step and provided some freedom for the sector from state dominance. Interviewees 3 and 4 (owners of private licenced bodies) have stressed that they had good communication and cooperation with the PFOs and indeed, 75% of the respondents agreed that the period from 2011 to 2014 was very favourable for PFOs regarding the management activities that took place in their private forests.

In most of the former socialist countries, both the number of legal changes and the impact of property rights changes were higher compared to those in Western Europe [12]. This is also the case in North Macedonia comparing the creation of LF and the number of amendments on LF. Property rights are considered an important aspect of forest management activities on private forest land. Effective forest (utilisation) management employs good forest planning and management that respect the owners’ rights and needs.

The interview data have revealed the problems PFOs are facing, particularly a lack of input into forest management plans and the implementation of executive forest plans as well as the time-consuming procedure to obtain licences for harvesting operations. Indeed, the survey data highlighted that in the period from 2011 to 2014, PFOs needed less time completing the procedure to obtain a harvesting licence, showing that oversight of the sector has become more bureaucratic in recent years. Furthermore, from 2011 to 2014, PFOs had access to additional advisory services from the private licenced bodies, a resource that is no longer available to them.

This change in circumstances was ushered in by the 2014 amendment to the LF when responsibility for forest management activities on private forest land was returned to the PENŠ. The majority of the respondents (86%) considered it an institutional step back and something that endangers the liberalisation process PFOs have been engaged in since the break-up of Yugoslavia. Knight [59] argues that distributional differences and power asymmetries are important for establishing laws rather than outcomes from individual interactions. This is obvious in many liberalisation processes when several stakeholders are involved but the state apparatus seeks to sustain its power and other rights by preserving its monopoly in a given sector or industry. The semi-structured interviews’ data identified possible reasons for this path dependency. The survey provides how important these reasons were. These data are presented as separate sets of statements included in the survey and are presented below in Table 2. Under each statement, the respondent was asked to give a score, and based on the score analysis of the survey data, two statements (4.1 and 4.4) clearly stand out in the respondents’ minds and appear to be the most important for introducing the 2014 amendment.

Table 2.

Identification of the importance of the reasons for introducing the 2014 amendment to the LF.

The law must depend on the spontaneously and evolved societal traditions, requiring the power and institutions of the state. The legislature must have the capacity to act proactively and under the socio-economic changes and needs, and PFOs’ needs were not considered before introducing the 2014 amendment. The Cambridge Dictionary defines democracy as “the belief in freedom and equality between people, or a system of government based on this belief, in which power is either held by elected representatives or directly by the people themselves.” Based on the third Ministerial Conference on the Protection of Forests in Europe (Lisbon, 1998), there is a need for forest advisory services for the PFO. These services need to be provided by the state. Provision of professionally technical, advisory, and extension services should be provided by independent institutions. The possibility for the PFOs to have the opportunity to choose between the PENŠ and private licenced bodies (statement 5.3) was fully supported or strongly agreed upon by all respondents.

5. Discussion

During the 1990s, there was a fundamental change in North Macedonian politics and society as it transitioned from socialism to democracy, a situation that is important to understand with regard to property rights and the degree to which the various actors’ perceptions of the control and ownership of property have kept pace with the transition process. According to Georgievski [50], the North Macedonian restitution process has, to a certain extent, failed “due to the numerous (administrative) weaknesses” and, therefore, “the implementation of the Law on Denationalisation was not properly applied”.

After independence, the forestry sector within the MAFWE and PENŠ continued with the neglecting role over private forest owners. The changes to the LF, with its various amendments, have resulted in a number of policy shifts; however, the situation as it currently stands is not significantly different from what existed during the socialist era. There is a need to identify the restrictions imposed on PFOs regarding forest management practices in their forests. The data from the interviews show that the PFOs’ focus on the use of their private forests for supplying materials for personal consumption, such as timber and firewood, has been realised to a certain extent. Receiving monetary gain is not realistic due to the restriction (allowed quantity) imposed by the management plans (developed by PENŠ). The incentives and subsidies for engaging in reforestation programmes and the conversion of the private (coppice) forests into high forests are still neglected. The legally binding and controlling policies typical of socialist systems were replaced by other types of policies (private rulemaking) [39]. The topic and issues of private forestry which were embraced and developed into the new policies at the beginning of this century have created a new coalition between the MAFWE and PENŠ instead of a controlling role of the MAFWE over PENŠ. This coalition brought about the enactment of the new policies, influencing them to stay on the existing path and ensuring the rules inherited from the previous system were transferred into the “new” policies. This view was reaffirmed by 87% (strongly agree or agree) of the respondents that there were no significant changes in forest policies during the period from 1991 to 2009 compared to the previous system.

Scholars have distinguished two forms of governance—“old governance” and “new governance” [60,61,62,63]. In old governance, a state steers its society and economy through political brokerage by defining goals and making priorities. “New governance” refers to facilitating coordination and coherence among a wide variety of private and public actors with different purposes and objectives [64]. Glück and Rayner [65] see new governance as the pattern or structure that emerges in a socio-political system as a “common” result or an outcome of the interacting intervention efforts of all the involved actors. The premise of new governance was born from the perceived failure of states’ hierarchical, top-down approach in policy formulation and implementation for addressing forest policy problems, which are characterised by complex issues and the presence of multiple actors seeking to achieve their own goals [60,63].

New governance models seek to embrace complexity and turn the presence of multiple actors from a problem into a solution [65]. According to Trendafilov [51], “the system where the services were under the jurisdiction of MAFWE functioned better than the system after, due to the conflict of interests of the PENŠ as management and as a service provider organisation at the same time”. With the LF entering into force in 2009, management practices on private forest land have remained under the auspices of the PENŠ, indicating that the influence of institutions from the socialist system and their respective approaches regarding forest management practices on private forest land are still in place. However, in (as a) former socialist states, it is expected the state should play a pivotal role and enjoy the position of supreme cultural authority and be responsible for the formation, dissemination, and reproduction of institutions, as well as ensuring their authority over society [58]. The drafting process of the 2014 amendment was non-transparent and took place without adequate representation of and input by all the key actors. Therefore, the new amendment was the logical result of the inputs from actors that participated (only representatives from ministry and PENŠ), resulting in policy regression that bolstered the position of the major public-sector actors [66].

The Republic of North Macedonia has had candidate status for entrance into the EU since 2005. This status obliges the country to harmonise its national legislation with EU policy and standards, which includes adopting some EU forest policies. Modern forestry relies on new modes of forest governance principles [67], particularly with regard to PFOs’ property rights that determine the amount of leeway given to forest owners to decide for themselves on the delivery of forest goods and services from their forests, within the bounds of the relevant laws [68]. In the work of Nichiforel, [12] a comparison was made between forest governance approaches implemented in Western Europe that provide considerable freedom to PFOs regarding decision making on their forests and the approaches of former socialist bloc countries, such as North Macedonia, which still have state-centred forest regulatory frameworks.

Implementation of the new governance in the forest sector in North Macedonia is still in its initial phase. Forest governance in North Macedonia, in terms of effectiveness, accountability, rule of the law, participation, and transparency, remain below par in comparison to many other European countries when drafting forest management plans [11]. The lack of these governance principles has negative impacts on the management of private forests as well [11]. The missing key aspect of a new governance approach in North Macedonia is the diversification of forest policy to move from being focused on one sectoral outcome (the sustained yield of timber) to a multi-sectoral focus that facilitates inter-sectoral coordination, policy integration, and actors’ interaction [65]. Policy development in this direction would be beneficial on many levels, not least of which is the fact that the implementation of new governance principles in North Macedonia’s forest policies would have a positive impact on institutional effectiveness and efficiency [65,67].

The HI perspective views institutions as the legacy of a concrete historical process and, within the context of this paper, these institutions are the persistent vestiges of the traditional forest sector that was/is dominated by public administration under a system that is reluctant to change. While significant change has indeed already occurred in North Macedonia, some old forest institutional forms and practices related to forest management activities on private forest land still exist and persist in their previous socialist shape. Institutions should not be viewed as uniform systems that structure policy outcomes but as packets of practice that can be shuffled, rearranged, changed, or used more routinely in particular circumstances [69]. There are cases where the role of actors can be crucial in, or a reason for, making choices about how to arrange the relevant institutions to fit the desired circumstances, as can be seen in the activity of the PENŠ lobby. In theory, institutionalists generally focus on the power of actors’ positions vis-a-vis other actors [22]. Since institutions privilege some interests, they can grant certain actors more access to, and hence, influence over, decision making than others. In North Macedonia’s case, this has played out with PENŠ gaining a level of access that has been denied to PFOs. This is one of the means used by institutional structures to not only influence power relations between actors but also to influence the trajectories of institutional developments [22,24,25,26].

It is most likely that the private forestry issues will be reframed in a way to fit into the current prevailing discourses and policy designs following the current forest sector trajectories. Integrating solutions into private forestry problems and concerns into broader forest policy domains requires a deep understanding of their rational principles, traditions, and strong political will, which is possible if there is existing effective national forest policy coordination.

It will be interesting to see how the path will further develop in the search for an efficient structure. As a result of joining the EU, the forest trajectory in North Macedonia can be influenced by the new EU policies such as the EU Forest Strategy, the Green Agenda for the Western Balkans, the EU Bioeconomy Strategy, and others. PFOs’ expectations are being raised that domestic policies will be required to substantially address some of the lacking new governance issues for private forests mentioned above to break the vicious circle of state-dominated forestry development. As previously noted, North Macedonian PFOs use their forests primarily to meet their own domestic needs (firewood), which differs from their EU counterparts where nature protection and recreation are the top priorities [70]. Corresponding to the prevailing economic interests, North Macedonian PFOs expect responsible forest management on private forest land from the entities responsible for such, as well as additional extension services regarding forest management planning. The additional services that are particularly sought after at the moment include advice on silviculture and harvesting, means to convert coppices to high forests and advice on reforestation. Some of these extension services were previously provided by private licenced bodies, which is a key factor driving PFOs wanting to have the option to select using the PENŠ or private licenced bodies to oversee their forest management activities. There is an almost universal demand from all the interviewed actors for subsidies to help them embrace sustainable forest management, finding a solution to resolve the ongoing cadastral problems and the reformulation of domestic forest laws to include the interests of private forest owners, including PFO representation in the North Macedonia’s political processes that directly impact them.

6. Conclusions

Forest policy in the Republic of North Macedonia is based on a strict regulatory framework inherited from the now-defunct socialist system. This framework performs largely as it did in the past by sustaining the state ownership of forests and keeping public sector actors, principally PENŠ, in dominant roles to maintain the status quo. As such, the institutionalisation of private forestry in North Macedonia is constrained by the legacy of the socialist system, which will require significant commitment and effort by all the sector’s actors’ to overcome. The recent series of changes to forest policy in North Macedonia has not been able to bring about substantive change in terms of sustainable forest management of private forests and, therefore, these reforms remain largely symbolic.

The progress made in North Macedonia in terms of reform in the period from 1991 to 2011 was typical of former socialist countries undergoing transition. The period from 2011 to 2014 saw great steps being taken towards de-institutionalising forest management activities on private forest land and introducing a genuine private forest sector (licenced bodies) coupled with efforts to implement a market economy approach to forestry. With the 2014 amendment to the LF, state control over forest management activities on private forest land returned and the institutionalisation of private forestry in North Macedonia returned to being fully embedded within a larger set of public institutions that survived the collapse of the socialist system. The earlier amendment, in 2011, changed the balance of power away from public sector actors, particularly PENŠ, which subsequently and successfully applied its influence to have the situation returned to the old status quo.

The PFOs have formed their expectations around the services for forest management activities on private forest land. The change of the rule (amendment from 2014) could have a long-term effect. The recent changes regarding private forestry indicate that an overarching goal has been set without an accompanying mix of instruments and consistency of practices in accordance with the good governance principles (accountability, transparency, etc.), influencing the changes in private forestry in North Macedonia to remain symbolic. As previously noted, policy integration typically unfolds in path-dependent processes. The HI perspective does not believe that the PFOs will robotically follow the rule or seek to use rules to maximise their own interests. The HI approach helps us to understand why certain choices were made, specifically with regard to the 2014 amendment, and why the outcomes we now see have occurred.

North Macedonia is committed to joining in EU, and the accession process requires the harmonisation of national and EU legislation and will result in some of the EU’s DI being transferred to the national forest policy. Environment policy has recently been moved to centre stage in EU policymaking, with the European Commission launching programmes such as the European Green Deal as key drivers of its economic growth strategy. These EU policies are built on good governance principles and these same principles need to be implemented at the national level within North Macedonia. The (new) forthcoming (EU-initiated) forest policy will ensure the integrity of PFOs is something needed for monitoring in the forthcoming period. This paper’s findings point to the need for good participative, accountable, and transparent processes for enabling PFOs to protect their rights to information and participation as one of the pre-conditions for creating effective policies that lead toward sustainable and responsible forest management, which is one of the goals of the European Green Deal and the Green Agenda for the Western Balkans.

Funding

The publishing of this paper was financially supported by the Forest Policy Research Network of the European Forest Institute, located at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, BOKU, Vienna.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented here is not publicly available because this research is not part of any other project and is individually sourced research undertaken by the author for his Ph.D. thesis. Due to the sensitivity of some issues in this paper, the author respects the interviewers’ confidentiality and anonymity.

Acknowledgments

The initial idea for this paper arose in the framework of the FP1201 FACESMAP COST Action (Forest Land Ownership Change in Europe: Significance for Management and Policy), which is supported by the EU Framework Programme Horizon 2020. Furthermore, this paper was improved with input derived from the summer school organised by the TN1401 CAPABAL COST Action (Capacity Building in Forest Policy and Governance in the Western Balkan Region). The author acknowledges the efforts of Reinhart Ceulemans, University of Antwerp (Belgium) for reviewing an earlier version of the text and giving useful advice for improvements. A special acknowledgement must also be given to Gerhard Weiss—Institute of Forest, Environmental and Natural Resource Policy at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, BOKU, Vienna for his revision and valuable comments in final version of the text.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of Interviewers.

Table A1.

List of Interviewers.

| Overview of Conducted Interviews | ||

|---|---|---|

| Interviewee Number | Person/Organisation | Duration of the Interview |

| (1) | Private forest owner | 50 min |

| (2) | Private forest owner | 55 min |

| (3) | Owner of registered licenced body | 40 min |

| (4) | Owners of registered licence body | 1 h |

| (5) | Expert in forest policy—Professor at Hans Em Faculty of Forest Sciences, Landscape Architecture and Environmental Engineering | 1 h |

| (6) | Consultant of forest and rural development—representing NGO | 50 min |

| (7) | Representative of PENŠ | 45 min |

| (8) | Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and the Water Economy—Forestry and Hunting Department | 65 min |

Appendix B. Semi-Structured Interviews

- Can you explain chronologically the policy changes regarding forest management practices on private land? How was the situation before 2009, during 2009–2014, and after 2014? What was the role of the actors during the policy changes regarding forest management practices on private land?

- Did you have the opportunity to participate in the process of creating forest policies? If yes—in what capacity and can you explain the role and impression you got from that process?

- Can you explain the role of PFOs in forest management practices on private forest land? Do they have freedom regarding forest management practices on private forest land? Please explain in more detail.

- In your opinion, what were the reasons for the amendment in 2014 and forbidding the activities of registered licence bodies? Please explain who is benefiting from the amendment in 2014.

- Can you give or provide some suggestions to overcome the current situation? What is the ideal situation for all actors regarding issues related to forest management practices on private forest land?

Appendix C

Table A2.

Survey Closed Questions Statements.

Table A2.

Survey Closed Questions Statements.

| 1.1. The situation regarding management activities on private forest land in the previous system (Yugoslavia) was very well regulated. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree |

| 1.2. During the period of 1991–2009 (the period after Yugoslavia’s disintegration until the FL (2009)), the situation remained the same as it was in the socialist system regarding forest management activities on private forest land. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree |

| 1.3. There were significant changes with the 2009 FL in the period from 2009 to 2011 regarding forest management activities on private forest land. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree |

| 1.4. The period of 2011–2014 is considered very favourable for PFOs regarding forest management activities on private forest land. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree |

| 1.5. The period after 2014 is considered as going back to bureaucracy. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree |

| 2.1 A participative approach was implemented during the creation of the 2009 FL. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree |

| 2.2 A participative approach was implemented during the creation of the amendments to the FL in 2011, 2013, and 2014. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree |

| 2.3 The process of drafting the 2009 FL was transparent. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree |

| 2.4 The process of drafting amendments to the FL in 2011, 2013, and 2014 was trans-parent. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree |

| 2.5 The PFOs and the NAPFO were consulted for the amendments in 2011 and 2013. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree |

| 2.6 The PFOs and the NAPFO were consulted for the amendments in 2014. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree |

| 3.1 After 2014, PFOs are completely free to manage their forests. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree |

| 3.2 The period from 2011 to 2014 secured the freedom for PFOs to choose regarding forest management activities on private forest land. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree |

| 3.3 There have been no changes in terms of liberalisation between the period of 2011–2014 and the period after 2014 regarding forest management activities on private forest land. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree |

| 4.1 How important was the PENŠ lobby for the amendment in 2014 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4.2 How important were the corruption and criminality of the licenced bodies for the amendment in 2014? | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4.3 How important was the national forest policy harmonisation with EU forest policies for the amendment in 2014? | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4.4 How important was the political interest for the amendment in 2014? | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5.1. The exclusivity of the PENŠ to perform activities regarding forest management on private forest land. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree |

| 5.2 The exclusivity of the private licenced bodies to perform activities regarding forest management on private forest land. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree |

| 5.3 The possibility of PFOs to select between PENŠ and private licenced bodies for performing activities regarding forest management on private forest land. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree |

References

- Weiland, S. Sustainability transitions in transition countries: Forest policy reforms in South-eastern Europe. Environ. Policy Gov. 2010, 20, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivojinovic, I.; Nedeljkovic, J.; Stojanovski, V.; Japelj, A.; Nonic, D.; Weiss, G.; Ludvig, A. Non-Timber Forest products in transition economies: Innovation cases in selected SEE countries. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 81, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiti, T. Economy: Basics of Economy; Ss. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje, Faculty of Economics: Skopje, North Macedonia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Živojinović, I.; Weiss, G.; Lidestav, G.; Feliciano, D.; Hujala, T.; Dobšinská, Z.; Lawrence, A.; Nybakk, E.; Quiroga, S.; Schraml, U. Forest Land Ownership Change in Europe. COST Action FP1201 FACESMAP Country Reports; University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences: Vienna, Austria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sarvašová, Z.; Zivojinovic, I.; Weiss, G.; Dobšinská, Z.; Drăgoi, M.; Gál, J.; Jarský, V.; Mizaraite, D.; Põllumäe, P.; Šálka, J.; et al. Forest owners associations in the Central and Eastern European region. Small-Scale For. 2015, 14, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovska, M. Report: Sub-Sctor Analysis of Private Forestry in Macedonia; CNVP—Connecting Natural Values and People: Skopje, North Macedonia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Netherlands Development Organisation—SNV. Sub-Sector Analysis of Private Forestry in Macedonia. Report. 2009. Available online: https://kipdf.com/sub-sector-analysis-of-private-forestry-in-macedonia-macedonia-connecting-natura_5ab76a481723dd349c81e2a6.html (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Deakin, S.; Gindis, D.; Hodson, M.G.; Huang, K.; Pistor, K. Legal institutionalism: Capitalism and the constitutive role of law. J. Comp. Econ. 2016, 45, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glück, P.; Avdibegovic, A.; Cabaravdic, A.; Nonic, D.; Petrovic, N.; Posavec, S.; Stojanovska, M.; Imocanin, S.; Krajter, S.; Lozanovska, N.; et al. The precondition for the formation of private forest owner’s interest association in Western Balkan Region. For. Policy Econ. 2010, 12, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Statistical Office of the Republic of North Macedonia. Annual Report for 2018. Available online: https://www.stat.gov.mk/OblastOpsto_en.aspx?id=18 (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Stojanovska, M.; Miovska, M.; Jovanovska, J.; Stojanovski, V. The process of forest management plans preparation in the Republic of Macedonia: Does it comprise governance principles of participation, transparency and accountability? For. Policy Econ. 2014, 49, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichiforel, L.; Deuffic, P.; Thorsen, B.J.; Weiss, G.; Hujala, T.; Keary, K.; Lawrence, A.; Avdibegović, M.; Dobšinská, Z.; Feliciano, D.; et al. Two decades of forest-related legislation changes in European countries analysed from a property rights perspective. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 115, 102146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alley, B. New institutionalist explanations for institutional change: A note of caution. Politics 2001, 21, 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, V.A. Taking ideas and discourse seriously: Explaining change through discursive institutionalism as the fourth ‘new institutionalism’. Eur. Political Sci. Rev. 2010, 2, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koontz, T.; Steelman, T.; Carmin, J.; Korfmacher, K.; Moseley, C.; Thomas, C. Collaborative Environmental Management: What Roles for Government? Resources for the Future Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Orren, K.; Skowronek, S. The Search for American Political Development; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, D.P. The Forging of Bureaucratic Autonomy: Reputations, Networks, and Policy Innovation in Executive Agencies, 1862–1928; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Skocpol, T. States and Social Revolutions: A Comparative Analysis of France, Russia, and China; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Pierson, P. Politics in Time: History, Institutions, and Social Analysis; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Krasner, S. Approaches to the State: Alternative Conceptions and Historical Dynamics. Comp. Politics 1984, 16, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, G. Institutional Theory in Political Science: The New Institutionalism, 2nd ed.; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, V.A. Discursive institutionalism: The explanatory power of ideas and discourse. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2008, 11, 303–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierson, P. Increasing returns, path dependence and the study of politics. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2000, 94, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowndes, V. Institutionalism. In Theories and Methods in Political Science, 2nd ed.; Marsh, D., Stoker, G., Eds.; Palgrave: London, UK, 2002; pp. 90–108. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, P.A.; Taylor, R.C.R. Political Science and the Three New Institutionalisms. Political Stud. 1996, 44, 936–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelble, T.A. The new institutionalism in political science and sociology. Comp. Politics 1995, 27, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J. Path Contingency in Postcommunist Transformations. Comp. Politics 2001, 33, 253–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, G. The promise of historical sociology in international relations. Int. Stud. Rev. 2006, 8, 397–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions of Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Calvert, R.L. Rational Choice Theory of Institutions: Implications for Design. In Institutional Design; Weimer, D., Ed.; Kluwer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Niskanen, W.A. Bureaucracy and Public Economics; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sproule-Jones, M. Governments at Work: Canadian Parliamentary Federalism and Its Public Policy Effects; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, C. Constructivist Institutionalism. In The Oxford Handbook of Political Institutions; Rhodes, R.A.W., Binder, S., Rockman, B., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, V.A. The Futures of European Capitalism; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, V.A. Values and Discourse in the Politics of Adjustment. In Welfare and Work in the Open Economy Volume I: From Vulnerability to Competitiveness; Scharpf, F.W., Schmidt, V.A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 229–309. [Google Scholar]

- Arts, B.; Buizer, M. Forest, discourses, institutions: A discursive-institutional analysis of global forest governance. For. Policy Econ. 2009, 11, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts, B. Forests policy analysis and theory use: Overview and trends. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 16, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, G.; Lawrence, A.; Lidestav, G.; Feliciano, D.; Hujala, T.; Sarvašová, Z.; Dobšinská, Z.; Živojinović, I. Research trends: Forest ownership in multiple perspectives. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 99, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, R.C.; Biklen, S.K. Qualitative Research for Education: An Introduction to Theory and Methods; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Shahab, S.; Lades, L.K. Sludge and transaction costs. Behav. Public Policy 2021, 3, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, S.; Clinch, J.P.; O’Neill, E. Estimates of transaction costs in transfer of development rights programs. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 2018, 84, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruebhausen, O.M.; Brim, O.G. Privacy and behavioral research. Am. Psychol. 1966, 21, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, L.E.; Zandecki, J.; Lo, B. The Certificate of Confidentiality application: A view from the NIH institutes. IRB Ethics Hum. Res. 2004, 26, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Gazette of Republic of North Macedonia No. 20/74: Law on Forests. 1974. Available online: http://www.slvesnik.com.mk/Issues/A13900384849485BA96D4F3F2B8FE59B.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Official Gazette of Republic of North Macedonia, No. 47/97: Law on Forests. 1997. Available online: http://www.slvesnik.com.mk/Issues/06CA1069589F4B9BB0D4EEC915249D72.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Official Gazette of Republic of North Macedonia No. 64/09: Law on Forests. 2009. Available online: http://www.slvesnik.com.mk/Issues/A01FA2B27040AF49A8655D855A7B4B9F.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Official Gazette of Republic of North Macedonia No. 20/98: Restitution Law. 1998. Available online: http://www.slvesnik.com.mk/Issues/0BBF5E41C5AE46E2B06DC1589D212599.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Georgievski, S. The Denationalization in Republic of Macedonia. Bull. Minist. Financ. 2000, 1, 34–35. Available online: https://finance.gov.mk/wp-content/uploads/2008/11/bilten11-2000.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2021). (In Macedonian).

- Trendafilov, A.; Atanasovska, J.R.; Simovski, B. Status quo analysis—Analysis of private forestry in Macedonia and its role in the National Forest Strategy process. In Confederation of European Forest Owners; Lover Print: Sopron, Hungary, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Siry, J.P.; McGinley, K.; Cubbage, F.W.; Bettinger, P. Forest tenure and sustainable Forest management. Open J. For. 2015, 5, 526–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]