Recovery of Pasteurization-Resistant Vibrio parahaemolyticus from Seafoods Using a Modified, Two-Step Enrichment

Abstract

1. Introduction

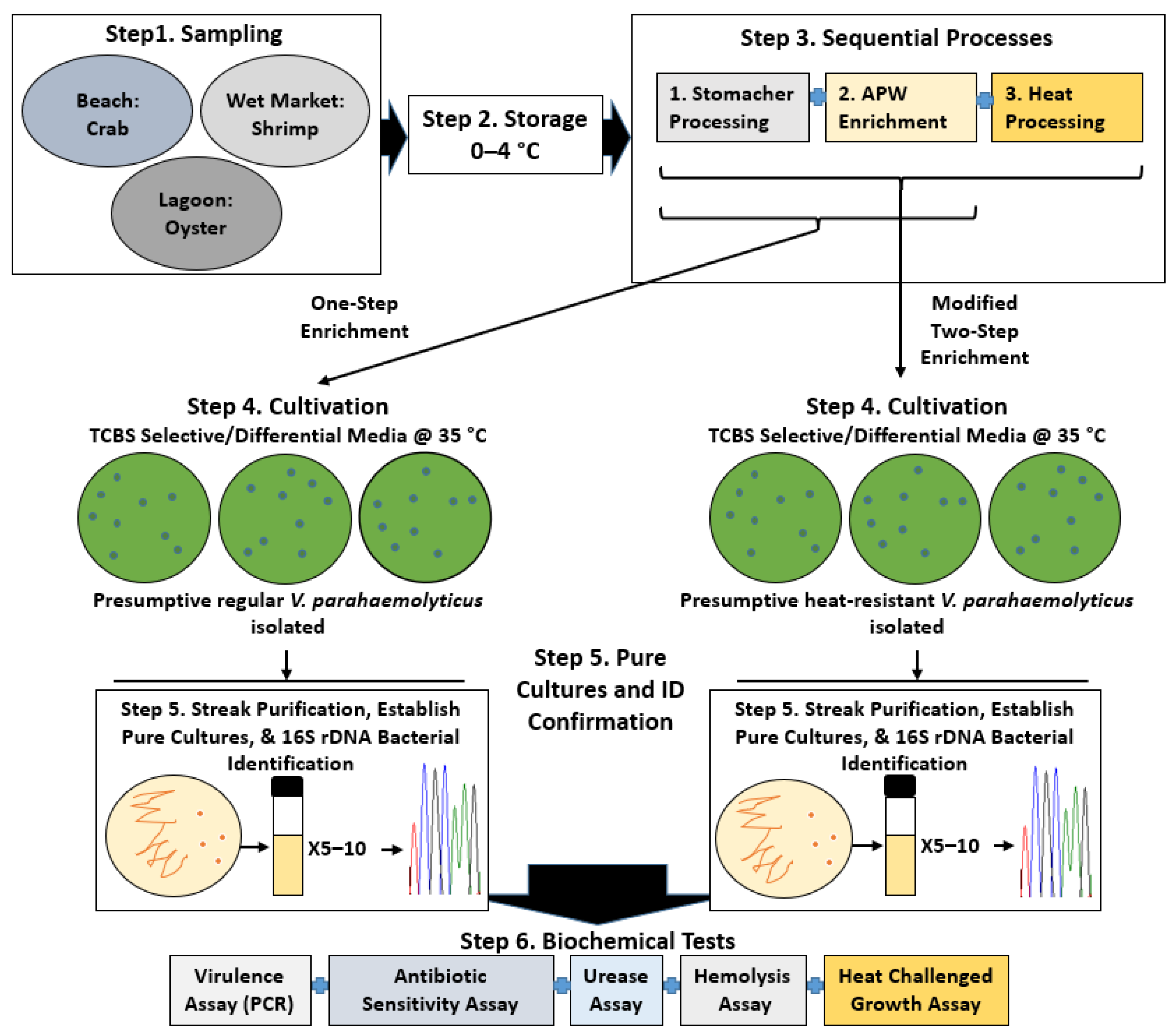

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

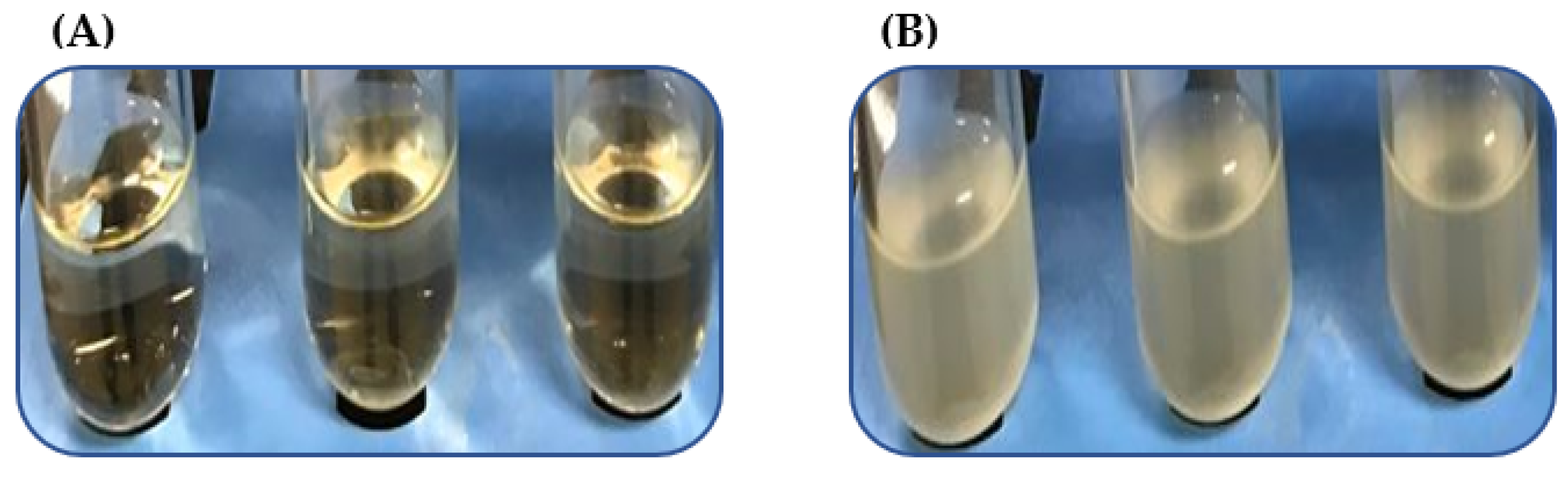

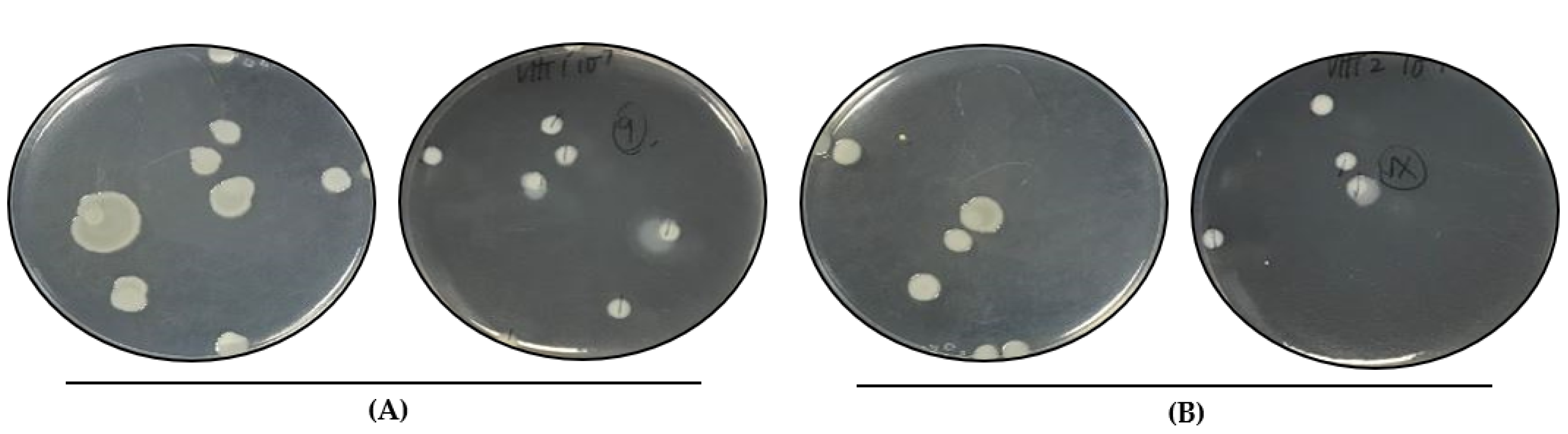

3.1. Colony Phenotype/Prevalence of V. parahaemolyticus from Thermally Treated Samples

3.2. Heat Resistance in Heat-Resistant V. parahaemolyticus Vegetative Cells

3.3. Virulence Determinants of the Heat-Resistant V. parahaemolyticus VHT1 and VHT2

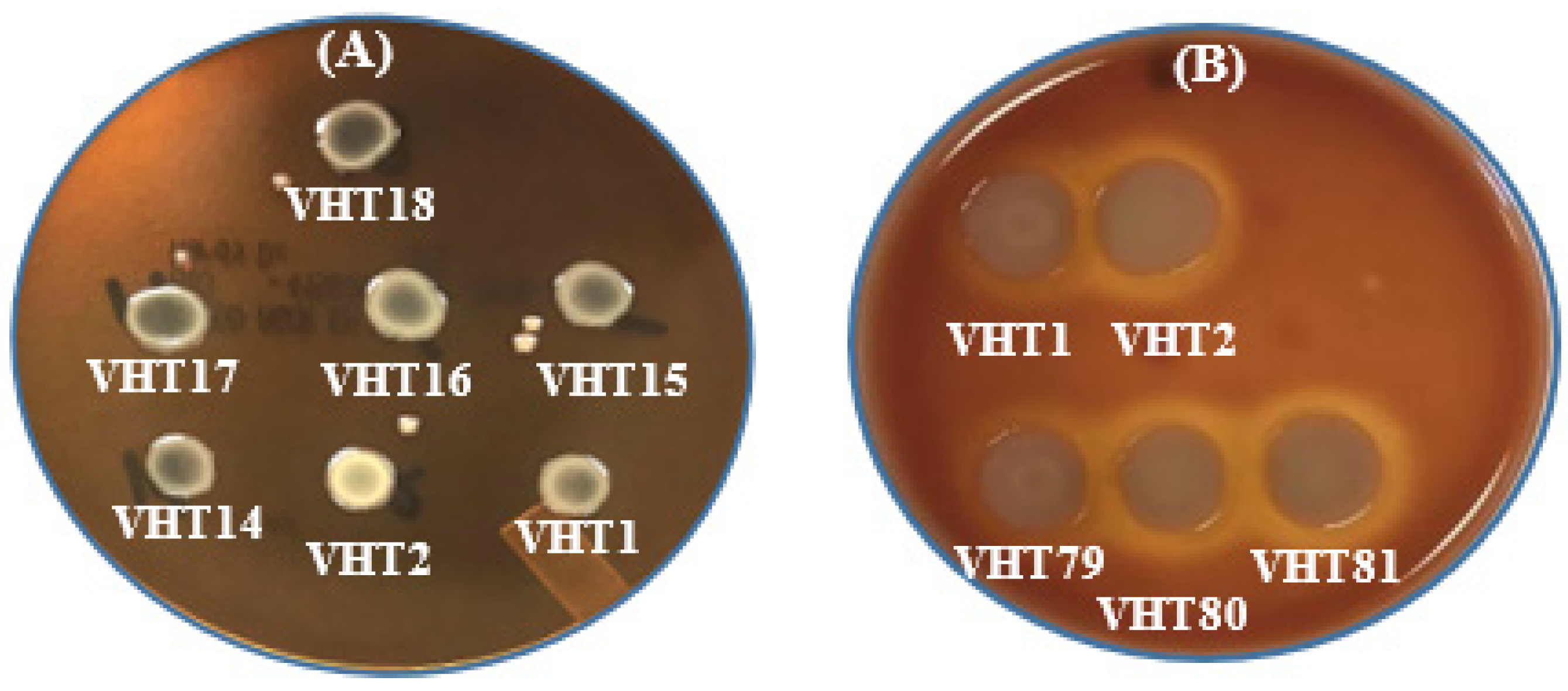

- Kanagawa phenomenon

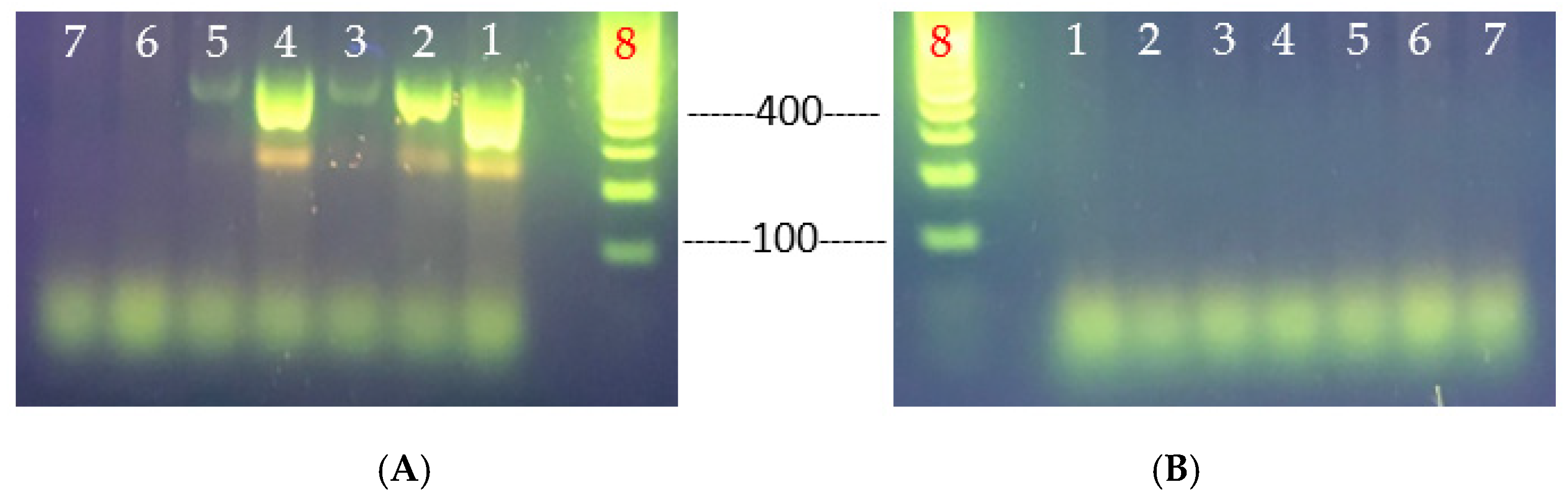

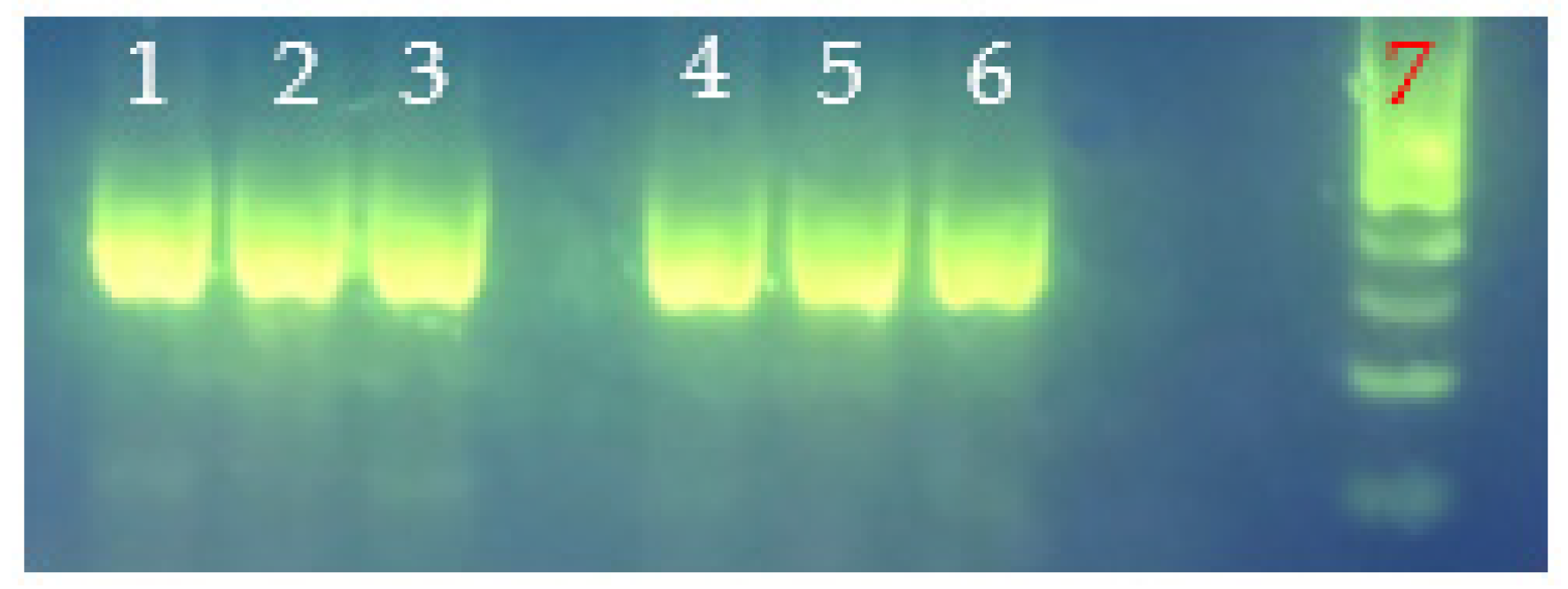

- PCR amplification of hemolysin genes

- Urease activity

3.4. Antibiotic Profile of the V. parahaemolyticus VHT1 and VHT2

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodrick, G.E. Indigenous pathogens: Vibrionaceae. In Microbiology of Marine Food Products, 1st ed.; Ward, D.R., Hackney, C., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1991; pp. 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broberg, C.A.; Calder, T.J.; Orth, K. Vibrio parahaemolyticus cell biology and pathogenicity determinants. Microbes Infect. 2011, 13, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odeyemi, O.A. Incidence and prevalence of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in seafood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 464–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarr, C.L.; Patel, J.S.; Puhr, N.D.; Sowers, E.G.; Bopp, C.A.; Strockbine, N.A. Identification of Vibrio Isolates by a multiplex PCR assay and rpoB sequence determination. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizunoe, Y.; Wai, S.N.; Ishikawa, T.; Takade, A.; Yoshida, S. Resuscitation of viable but nonculturable cells of Vibrio parahaemolyticus induced at low temperature under starvation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2000, 186, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vibrio Species Causing Vibriosis. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vibrio/healthcare.html (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Sims, J.N.; Isokpehi, R.D.; Cooper, G.A.; Bass, M.P.; Brown, S.D.; St John, A.L.; Gulig, P.A.; Cohly, H.H. Visual analytics of surveillance data on foodborne vibriosis, United States, 1973–2010. Environ. Health Insights 2011, 5, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Urtaza, J.; Bowers, J.C.; Trinanes, J.; DePaola, A. Climate anomalies and the increasing risk of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus illnesses. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 1780–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xie, T.; Pang, R.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Lei, T.; Xue, L.; Wu, H.; Wang, J.; Ding, Y.; et al. Food-Borne Vibrio parahaemolyticus in China: Prevalence, antibiotic susceptibility, and genetic characterization. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vibrio Species Causing Vibriosis. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vibrio/surveillance.html (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Estimates of Foodborne Illness in the United States. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/foodborneburden/index.html (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Yang, Y.; Xie, J.F.; Li, H.; Tan, S.W.; Chen, Y.F.; Yu, H. Prevalence, antibiotic susceptibility and diversity of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolates in seafood from south China. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, S.A.; DePaola, A.; Cook, D.W.; Kaysner, C.A.; Hill, W.E. Evaluation of alkaline phosphatase- and digoxigenin-labelled probes for detection of the thermolabile hemolysin (tlh) gene of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1999, 28, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, A.; Kendall, M.; Vugia, D.J.; Henao, O.L.; Mahon, B.E. Increasing rates of vibriosis in the United States, 1996–2010: Review of surveillance data from 2 systems. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, S391–S395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safe Minimum Internal Temperature Chart. Available online: https://www.fsis.usda.gov/food-safety/safe-food-handling-and-preparation/food-safety-basics/safe-temperature-chart (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Gutierrez, C.K.; Klein, S.L.; Lovell, C.R. High frequency of virulence factor genes tdh, trh, and tlh in Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains isolated from a pristine estuary. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 2247–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinanes, J.; Martinez-Urtaza, J. Future scenarios of risk of Vibrio infections in a warming planet: A global mapping study. Lancet Planet Health 2021, 5, e426–e435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letchumanan, V.; Yin, W.F.; Lee, L.H.; Chan, K.G. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from retail shrimps in Malaysia. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghunath, P. Roles of thermostable direct hemolysin (TDH) and TDH-related hemolysin (TRH) in Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhong, Y.; Gu, X.; Yuan, J.; Saeed, A.F.; Wang, S. The pathogenesis, detection, and prevention of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuda, J.; Ishibashi, M.; Hayakawa, E.; Nishino, T.; Takeda, Y.; Mukhopadhyay, A.K.; Garg, S.; Bhattacharya, S.K.; Nair, G.B.; Nishibuchi, M. Emergence of a unique O3:K6 clone of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Calcutta, India, and isolation of strains from the same clonal group from Southeast Asian travelers arriving in Japan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1997, 35, 3150–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terano, H.; Takahashi, K.; Sakakibara, Y. Characterization of spore germination of a thermoacidophilic spore-forming bacterium, Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2005, 69, 1217–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara-Kudo, Y.; Nishina, T.; Nakagawa, H.; Konuma, H.; Hasegawa, J.; Kumagai, S. Improved method for detection of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in seafood. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 5819–5823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Agency (FDA). Bacteriological Analytical Manual (BAM) Chapter 9: Vibrio. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/laboratory-methods-food/bam-chapter-9-vibrio (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- DePaola, A.; Motes, M.L. Isolation of Vibrio parahaemolyticus from wild raccoons in Florida. In Vibrios in the Environment, 1st ed.; Colwell, R.R., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1984; pp. 563–566. [Google Scholar]

- DePaola, A.; Kaysner, C.A.; McPhearson, R.M. Elevated temperature method for recovery of Vibrio cholerae from oysters (Crassostrea gigas). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1987, 53, 1181–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, A.; Grim, C.; Colwell, R.R.; Nair, G.B. Detection, isolation, and identification of Vibrio cholerae from the environment. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 2006, 2, 6A.5.1–6A.5.38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Chowdhury, W.B.; Bhuiyan, N.A.; Islam, A.; Hasan, N.A.; Nair, G.B.; Watanabe, H.; Siddique, A.K.; Huq, A.; Sack, R.B.; et al. Serogroup, virulence and genetic traits of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in the estuarine ecosystem of Bangladesh. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 6268–6274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, J.D. Recent findings on the viable but nonculturable state in pathogenic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 34, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huq, A.; Haley, B.J.; Taviani, E.; Chen, A.; Hasan, N.A.; Colwell, R.R. Detection, isolation, and identification of Vibrio cholerae from the environment. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 2012, 26, 6A.5.1–6A.5.51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otomo, Y.; Hossain, F.; Rabbi, F.; Yakuwa, Y.; Ahsan, C.R. Pre-enrichment of estuarine and fresh water environmental samples with sodium chloride yields in better recovery of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Adv. Microbiol. 2015, 3, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmore, R.P., Jr.; Crisley, F.D. Thermal Resistance of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in clam homogenate. J. Food Prot. 1979, 42, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, L.S.; DeBlanc, S.; Veal, C.D.; Park, D.L. Response of Vibrio parahaemolyticus 03:K6 to a hot water/cold shock pasteurization process. Food Addit. Contam. 2003, 20, 331–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.C.; Chang, T.C. Rapid detection of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in oysters by immunofluorescence microscopy. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1996, 29, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipp, E.K.; Rivera, I.N.G.; Gil, A.I.; Espeland, E.M.; Choopun, N.; Louis, V.R.; Russek-Cohen, E.; Huq, A.; Colwell, R.R. Direct Detection of Vibrio cholerae and ctxA in Peruvian coastal water and plankton by PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 3676–3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.T.; Kim, Y.O.; Kong, I.S. Multiplex PCR for the detection and differentiation of Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains using the groEL, tdh and trh genes. Mol. Cell Probes 2013, 27, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Abad, V.; Ansede-Bermejo, J.; Rodriguez-Castro, A.; Martinez-Urtaza, J. Evaluation of different procedures for the optimized detection of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in mussels and environmental samples. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 129, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letchumanan, V.; Chan, K.G.; Lee, L.H. Vibrio parahaemolyticus: A review on the pathogenesis, prevalence, and advance molecular identification techniques. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamai, S.; Okitsu, T.; Shimada, T.; Katsube, Y. Distribution of serogroups of Vibrio cholerae non-O1 non-O139 with specific reference to their ability to produce cholera toxin, and addition of novel serogroups. J. Jpn. Assoc. Infect. Dis. 1997, 71, 1037–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.W.; Ab Mutalib, N.S.; Chan, K.G.; Lee, L.H. Rapid methods for the detection of foodborne bacterial pathogens: Principles, applications, advantages and limitations. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 5, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara-Kudo, Y.; Sugiyama, K.; Nishibuchi, M.; Chowdhury, A.; Yatsuyanagi, J.; Ohtomo, Y.; Saito, A.; Nagano, H.; Nishina, T.; Nakagawa, H.; et al. Prevalence of pandemic thermostable direct hemolysin-producing Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6 in seafood and the coastal environment in Japan. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 3883–3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, H.C.; Peng, P.Y.; Lan, S.L.; Chen, Y.C.; Lu, K.H.; Shen, C.T.; Lan, S.F. Effects of heat shock on the thermotolerance, protein composition, and toxin production of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Food Prot. 2002, 65, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiong, H.K.; Muriana, P.M. RT-qPCR analysis of 15 genes encoding putative surface proteins involved in adherence of Listeria monocytogenes. Pathogens 2016, 5, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, M.A.; Shoskes, D.; Shahed, A.; Pace, N.R. Prevalence of corynebacterial 16S rRNA sequences in patients with bacterial and “nonbacterial” prostatitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1999, 37, 1863–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, L.N.; Bej, A.K. Detection of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in shellfish by use of multiplexed real-time PCR with TaqMan fluorescent probes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 2031–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.W.; Malcolm, T.; Kuan, C.H.; Thung, T.Y.; Chang, W.S.; Loo, Y.Y.; Premarathne, J.; Ramzi, O.B.; Norshafawatie, M.; Yusralimuna, N.; et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from short mackerels (Rastrelliger brachysoma) in Malaysia. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Methods for Antimicrobial Dilution and Disk Susceptibility Testing of Infrequently Isolated or Fastidious Bacteria, 3rd ed.; CLSI guideline M45; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Urmersbach, S.; Aho, T.; Alter, T.; Hassan, S.S.; Autio, R.; Huehn, S. Changes in global gene expression of Vibrio parahaemolyticus induced by cold- and heat-stress. BMC Microbiol. 2015, 15, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Walker, R.D.; Janes, M.E.; Prinyawiwatkul, W.; Ge, B. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus isolates from Louisiana Gulf and retail raw oysters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 7096–7098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, K.C.; Brown, A.M.; Luscombe, G.M.; Wong, S.J.; Mendis, K. Antibiotic use for Vibrio infections: Important insights from surveillance data. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayrapetyan, M.; Williams, T.; Oliver, J.D. Relationship between the Viable but Nonculturable State and Antibiotic Persister Cells. J. Bacteriol. 2018, 200, e00249-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Q.; Wang, B.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Fang, X.; Liao, Z. Global proteomic analysis of the resuscitation state of Vibrio parahaemolyticus compared with the normal and viable but non-culturable state. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Kahla-Nakbi, A.; Besbes, A.; Chaieb, K.; Rouabhia, M.; Bakhrouf, A. Survival of Vibrio alginolyticus in seawater and retention of virulence of its starved cells. Mar. Environ. Res. 2007, 64, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoussi, M.; Noumi, E.; Cheriaa, J.; Usai, D.; Sechi, L.A.; Zanetti, S.; Bakhrouf, A. Adhesive properties of environmental Vibrio alginolyticus strains to biotic and abiotic surfaces. New Microbiol. 2008, 31, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu, F.; Ilyas, S.; Hall, J.A.; Jones, S.H.; Cooper, V.S.; Whistler, C.A. Genetic characterization of clinical and environmental Vibrio parahaemolyticus from the Northeast USA reveals emerging resident and non-indigenous pathogen lineages. Front. Microb. 2015, 6, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.S.; Parvathi, A.; Karunasagar, I.; Karunasagar, I. A gyrB-based PCR for the detection of Vibrio vulnificus and its application for direct detection of this pathogen in oyster enrichment broths. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 111, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cebrián, G.; Condón, S.; Mañas, P. Physiology of the inactivation of vegetative bacteria by thermal treatments: Mode of action, influence of environmental factors and inactivation kinetics. Foods 2017, 6, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.V.; Varadaraj, M.C. Behavioural pattern of vegetative cells and spores of Bacillus cereus as affected by time-temperature combinations used in processing of Indian traditional foods. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 47, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bukau, B. Regulation of the Escherichia coli heat-shock response. Mol. Microbiol. 1993, 9, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, A.D. Lethal effects of heat on bacterial physiology and structure. Sci. Prog. 2003, 86 Pt 1–2, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paracini, N.; Clifton, L.A.; Skoda, M.W.A.; Lakey, J.H. Liquid crystalline bacterial outer membranes are critical for antibiotic susceptibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E7587–E7594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Honda, T.; Ming, X. Construction and characterization of an isogenic mutant of Vibrio parahaemolyticus having a deletion in the thermostable direct hemolysin-related hemolysin gene (trh). J. Bact. 1994, 176, 4757–4760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.P.; Zhang, J.L.; Jiang, T.; Bao, Y.X.; Zhou, X.M. Insufficiency of the Kanagawa hemolytic test for detecting pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Shanghai, China. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2011, 69, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, J.; Ishibashi, M.; Abbott, S.L.; Janda, J.M.; Nishibuchi, M. Analysis of the thermostable direct hemolysin (tdh) gene and the tdh-related hemolysin (trh) genes in urease-positive strains of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated on the West Coast of the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1997, 35, 1965–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.S.; Iida, T.; Yamaichi, Y.; Oyagi, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Honda, T. Genetic characterization of DNA region containing the trh and ure genes of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 5742–8748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, S.; Matsumoto, S.; Miwatani, T.; Honda, T. A survey of urease-positive Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains isolated from traveller’s diarrhea, sea water and imported frozen sea foods. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 1992, 8, 861–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, M.I.; Huber, D.; Kibryia, G. Isolation of urease producing Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains from cases of gastroenteritis. Indian J. Med. Res. 1979, 70, 549–553. [Google Scholar]

- Suthienkul, O.; Ishibashi, M.; Iida, T.; Nettip, N.; Supavej, S.; Eampokalap, B.; Makino, M.; Honda, T. Urease production correlates with possession of the trh gene in Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains isolated in Thailand. J. Infect. Dis. 1995, 172, 1405–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eko, F.O. Urease production in Vibrio parahaemolyticus: A potential marker for virulence. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 1992, 8, 627–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osawa, R.; Okitsu, T.; Morozumi, H.; Yamai, S. Occurrence of urease-positive Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Kanagawa, Japan, with specific reference to presence of thermostable direct hemolysin (TDH) and the TDH-related-hemolysin genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996, 62, 725–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, H.Y.; Na, E.J.; Lee, K.H.; Ryu, S.; Yoon, H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.B.; Kim, H.; Choi, S.H.; Kim, B.S. Complete genome sequence of Vibrio parahaemolyticus FORC_023 isolated from raw fish storage water. Pathog. Dis. 2016, 74, ftw032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elexson, N.; Afsah-Hejri, L.; Rukayadi, Y.; Soopna, P.; Lee, H.Y.; Tuan Zainazor, T.C.; Son, R. Effect of detergents as antibacterial agents on biofilm of antibiotics-resistant Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolates. Food Control 2014, 35, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishir, M.A.; Mamun, M.A.; Mian, M.M.; Ferdous, U.T.; Akter, N.J.; Suravi, R.S.; Datta, S.; Kabir, M.E. Prevalence of Vibrio cholerae in coastal alternative supplies of drinking water and association with Bacillus-like spore formers. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzulli, L.; Grande, C.; Reid, P.C.; Hélaouët, P.; Edwards, M.; Höfle, M.G.; Brettar, I.; Colwell, R.R.; Pruzzo, C. Climate influence on Vibrio and associated human diseases during the past half-century in the coastal North Atlantic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E5062–E5071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, Y.; Yamauchi, S.; Fukata, S.; Okuyama, H.; Morita, E.; Shelake, R.; Hayashi, H. Heterologous expression of thermolabile proteins enhances thermotolerance in Escherichia coli. Adv. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Macaluso, A.; Best, E.A.; Bender, R.A. Role of the nac gene product in the nitrogen regulation of some NTR-regulated operons of Klebsiella aerogenes. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 7249–7255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sissons, C.H.; Perinpanayagam, H.E.R.; Hancock, E.M.; Cutress, T.W. pH regulation of urease levels in Streptoccus salivarius. J. Dent. Res. 1990, 69, 1131–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, E.B.; Concaugh, E.A.; Foxall, P.A.; Island, M.D.; Mobley, H.L.T. Proteus mirabilis urease: Transcriptional regulation by ureR. J. Bacteriol. 1993, 175, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berutti, T.R.; Williams, R.E.; Shen, S.; Taylor, M.M.; Grimes, D.J. Prevalence of urease in Vibrio parahaemolyticus from the Mississippi Sound. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 58, 624–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, J.M.; Webber, M.A.; Baylay, A.J.; Ogbolu, D.O.; Piddock, L.J. Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, C.D.; Godoy, F.A.; Lee, M.R. Current status of the use of antibiotics and the antimicrobial resistance in the Chilean Salmon Farms. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.W.; Rukayadi, Y.; Hasan, H.; Thung, T.Y.; Lee, E.; Rollon, W.D.; Hara, H.; Kayali, A.Y.; Nishibuchi, M.; Radu, S. Prevalence and antibiotic resistance patterns of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from different types of seafood in Selangor, Malaysia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 1602–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Seafood Species | Source | Sample # | Storage Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crab | Beach | 2 | 4 °C |

| Shrimp | Wet-market | 3 | 4 °C |

| Oyster | Lagoon | 3 | 4 °C |

| Gene ID | Primer | Amplicon Size | Melting Temperature | Annealing Temperature | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S-515 | F-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA | 900 | 65.2 | 56 | [44] |

| 16S-1391 | R-GACGGGCGGTGTGTRCA | 59.8 | 56 | ||

| tdh | F-GTARAGGTCTCTGACTTTTGGAC | 229 | 66 | 56 | [45] |

| R-CTACAGAATYATAGGAATGTTGAAG | 66 | 56 | |||

| tlh | F-AAAGCGGATTATGCAGAAGCACTG | 450 | 70 | 56 | [45] |

| R-GCTACTTTCTAGCATTTTCTCTGC | 68 | 56 |

| Seafood Species | Enrichment Only Incubation (h) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 24 | 48 | 72 | |

| Crab | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Shrimp | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| Oyster | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Seafood Species | Enrichment Incubation (h) + Heat 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 24 | 48 | 72 | |

| Crab | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Shrimp | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| Oyster | − | − | + | − | − | + | − |

| Isolate ID 1 | Isolation Mode 2 | Enrichment Time (h) | Sample Type | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VHT1 | Modified two-step | 48 | Oyster | Lagoon |

| VHT2 | Modified two-step | 48 | Oyster | Lagoon |

| VHT14 | Modified two-step | 48 | Oyster | Lagoon |

| VHT15 | Modified two-step | 48 | Oyster | Lagoon |

| VHT16 | Modified two-step | 48 | Oyster | Lagoon |

| VHT17 | one-step | 24 | Oyster | Lagoon |

| VHT18 | one-step | 24 | Oyster | Lagoon |

| VHT20 | one-step | 24 | Oyster | Lagoon |

| VHT21 | one-step | 24 | Oyster | Lagoon |

| VHT22 | one-step | 72 | Oyster | Lagoon |

| VHT25 | one-step | 72 | Oyster | Lagoon |

| VHT26 | one-step | 72 | Oyster | Lagoon |

| VHT79 | Pasteurization | NA | NA | VHT1 derivative |

| VHT80 | Pasteurization | NA | NA | VHT2 derivative |

| VHT81 | Pasteurization | NA | NA | VHT2 derivative |

| Isolate ID 1 | 62 °C 2 | 80 °C 3 |

|---|---|---|

| VHT1 | + | − |

| VHT2 | +++ | − |

| Isolate ID | Urease Activity 1 | tdh2 | tlh2 | KP3 | KPs4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VHT1 | +++ | − | + | + | − |

| VHT2 | ++ | − | + | + | − |

| VHT14 | ++ | − | + | ND | − |

| VHT15 | ++ | − | + | ND | − |

| VHT16 | + | − | + | ND | − |

| VHT17 | + | − | − | ND | − |

| VHT18 | ++ | − | − | ND | − |

| VHT79 | ND | ND | + | + | ND |

| VHT80 | ND | ND | + | + | ND |

| VHT81 | ND | ND | + | + | ND |

| Susceptibility Interpretive Data * | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VHT1 | VHT2 | |||||

| Antibiotic | Resistant | Intermediate | Sensitive | Resistant | Intermediate | Sensitive |

| CHL (30 µg) | v | v | ||||

| CIP (5 µg) | v | v | ||||

| ERY (15 µg) | v | v | ||||

| GEN (10 µg) | v | v | ||||

| NAL (30 µg) | v | v | ||||

| NEO (30 µg) | v | v | ||||

| PEN (10 µg) | v | v | ||||

| STR (10 µg) | v | v | ||||

| TET (30 µg) | v | v | ||||

| MAR Index | 0.22 | 0.22 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meza, G.; Majrshi, H.; Tiong, H.K. Recovery of Pasteurization-Resistant Vibrio parahaemolyticus from Seafoods Using a Modified, Two-Step Enrichment. Foods 2022, 11, 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11050764

Meza G, Majrshi H, Tiong HK. Recovery of Pasteurization-Resistant Vibrio parahaemolyticus from Seafoods Using a Modified, Two-Step Enrichment. Foods. 2022; 11(5):764. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11050764

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeza, Guadalupe, Hussain Majrshi, and Hung King Tiong. 2022. "Recovery of Pasteurization-Resistant Vibrio parahaemolyticus from Seafoods Using a Modified, Two-Step Enrichment" Foods 11, no. 5: 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11050764

APA StyleMeza, G., Majrshi, H., & Tiong, H. K. (2022). Recovery of Pasteurization-Resistant Vibrio parahaemolyticus from Seafoods Using a Modified, Two-Step Enrichment. Foods, 11(5), 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11050764