Coping Strategies and Burden Dimensions of Family Caregivers for People Diagnosed with Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

- The burden of the caregivers of patients diagnosed with OCD is associated with coping strategies;

- The burden of the caregivers of patients diagnosed with OCD is associated with distress (resulting from the worsening of the OCD symptoms);

- Coping strategies have a mediating role in caregiver burden and distress.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Data Collection Tool

3.3. Data Collection Procedure

3.4. Ethical Approval

3.5. Maintaining Confidentiality

3.6. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics for Family Members with OCD Symptom Severity and for Caregivers’ Burden and Coping Score

4.2. Relationship between Symptom Severity of Family Members with OCD and Their Caregivers’ Burden and Coping Score

4.3. Relationship between Caregivers’ Burden and Coping Score and Demographic Data

4.4. Relationship between OCD Severity and Aspects of Burden

4.5. Results under the Lens of the Theoretical Framework

5. Discussion

6. Study Implications

7. Study Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stengler-Wenzke, K.; Kroll, M.; Matschinger, H.; Angermeyer, M.C. Subjective quality of life of patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2006, 41, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, U.; Baffa, A.; Maina, G. Family accommodation in adult obsessive–compulsive disorder: Clinical perspectives. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2017, 10, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Grover, S.; Dutt, A. Perceived burden and quality of life of caregivers in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 65, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suculluoglu-Dikici, D.; Cokmus, F.P.; Akin, F.; Eser, E.; Demet, M.M. Disease burden and associated factors in caregivers of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Dusunen Adam. 2020, 33, 421–428. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, A.R.; Fontenelle, L.F.; Shavitt, R.G.; Hoexter, M.Q.; Pittenger, C.H.; Miguel, E.C. Epidemiology, comorbidity, and burden of OCD. In Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Phenomenology, Pathophysiology, and Treatment; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S.; Dunkel-Schetter, C.; DeLongis, A.; Gruen, R.J. Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 50, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, L.; Basri, S.; Alsahafi, F.; Altaylouni, M.; Albugumi, S.; Banakhar, M.; Mahsoon, A.; Alasmee, N.; Wright, R.J. An Exploration of Family Caregiver Experiences of Burden and Coping While Caring for People with Mental Disorders in Saudi Arabia—A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, A.R.; Hoff, N.T.; Padovani, C.R.; Ramos Cerqueira, A.T. Dimensional analysis of burden in family caregivers of patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 66, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.D.; Wang, C.H.; Li, H.F.; Zhang, X.L.; Zhang, Y.L.; Hou, Y.H.; Liu, X.H.; Hu, X.Z. Cognitive-coping therapy for obsessive–compulsive disorder: A randomized controlled trial. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 1785–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, J.B.; First, M. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chadda, R.K. Caring for the family caregivers of persons with mental illness. Indian J. Psychiatry 2014, 56, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carretero, S.; Garcés, J.; Ródenas, F.; Sanjosé, V. The informal caregiver’s burden of dependent people: Theory and empirical review. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2009, 49, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lu, N.; Liu, J.; Wang, F.; Lou, V.W. Caring for disabled older adults with musculoskeletal conditions: A transactional model of caregiver burden, coping strategies, and depressive symptoms. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2017, 69, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.L.; Guimarães, R.A.; de Araújo Vilela, D.; de Assis, R.M.; Oliveira, L.M.; Souza, M.R.; Nogueira, D.J.; Barbosa, M.A. Factors associated with the burden of family caregivers of patients with mental disorders: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bujang, M.A.; Baharum, N. Sample size guideline for correlation analysis. World J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2016, 3, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, W.K.; Price, L.H.; Rasmussen, S.A.; Mazure, C.; Fleischmann, R.L.; Hill, C.L.; Heninger, G.R.; Charney, D.S. The Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale: I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1989, 46, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thara, R.; Padmavati, R.; Kumar, S.; Srinivasan, L. Instrument to assess burden on caregivers of chronic mentally ill. Indian J. Psychiatry 1998, 40, 21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hamby, S.; Grych, J.; Banyard, V.L. Life Paths Research Measurement Packet; Life Paths Research Program: Sewanee, TN, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zahid, M.A.; Ohaeri, J.U. Relationship of family caregiver burden with quality of care and psychopathology in a sample of Arab subjects with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Demirbağ, B.C.; Özkan, Ç.G.; Bayrak, B.; Kurt, Y. Caregiver burden and responsibilities for nurses to reduce burnout. In Caregiving and Home Care; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves-Pereira, M.; van Wijngaarden, B.; Xavier, M.; Papoila, A.L.; Caldas-de-Almeida, J.M.; Schene, A.H. Caregiving in severe mental illness: The psychometric properties of the Involvement evaluation questionnaire in Portugal. Ann Gen. Psychiatry 2012, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Wijngaarden, B.; Schene, A.H.; Koeter, M.W.J.; Vázquez-Barquero, J.L.; Knudsen, H.C.; Lasalvia, A.; McCrone, P. Caregiving in schizophrenia: Development, internal cons consistency and reliability of the Involvement evaluation questionnaire-European version. Br. J. Psychiatry 2000, 177, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Balkaran, B.L.; Jaffe, D.H.; Umuhire, D.; Rive, B.; Milz, R.U. Self-reported burden of caregiver of adults with depression: A cross-sectional study in five Western European countries. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.; Lakshmi, V. The burden of schizophrenia on caregivers: A review. Pharmacoeconomics 2008, 26, 149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Yükü, K.R.; Derleme, S. Caregiver burden in chronic mental illness: A systematic review. J. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2017, 8, 165–171. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.T. Dementia caregiver burden: A research update and critical analysis. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bhattacharjee, M.; Vairale, J.; Gawali, K.; Dalal, P.M. Factors affecting burden on caregivers of stroke survivors: Population-based study in Mumbai (India). Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2012, 15, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmoneium, A.O.; Alharahsheh, S.T. Family home caregivers for old persons in the Arab region: Perceived challenges and policy implications. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 14, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aggarwal, M.; Avasthi, A.; Kumar, S.; Grover, S. Experience of caregiving in schizophrenia: A study from India. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2011, 57, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geffken, G.R.; Storch, E.A.; Duke, D.C.; Monaco, L.; Lewin, A.B.; Goodman, W.K. Hope and coping in family members of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Anxiety Disord. 2006, 20, 614–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunwar, D.; Lamichhane, S.; Pradhan, N.; Shrestha, B.; Khadka, S.; Gautam, K.; Risal, A. The study of burden of family caregivers of patients living with psychiatric disorders in remote area of Nepal. Kathmandu Univ. Med. J. 2020, 18, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sücüllüoğlu Dikici, D.; Eser, E.; Çökmüş, F.P.; Demet, M.M. Quality of life and associated risk factors in caregivers of patients with obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 29, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pedley, R.; Bee, P.; Berry, K.; Wearden, A. Separating obsessive-compulsive disorder from the self. A qualitative study of family member perceptions. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walseth, L.T.; Haaland, V.Ø.; Launes, G.; Himle, J.; Håland, Å.T. Obsessive-compulsive disorder’s impact on partner relationships: A qualitative study. J. Fam. Psychother. 2017, 28, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oza, H.; Parikh, M.N.; Vankar, G.K. Comparison of caregiver burden in schizophrenia and obsessive–compulsive disorder. Arch Psychiatry Psychother 2017, 2, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimshoni, Y.; Shrinivasa, B.; Cherian, A.V.; Lebowitz, E.R. Family accommodation in psychopathology: A synthesized review. Indian J. Psychiatry 2019, 61 (Suppl. S1), S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koujalgi, S.R.; Nayak, R.B.; Pandurangi, A.A.; Patil, N.M. Family functioning in patients with obsessive compulsive disorder: A case-control study. Med. J. Dr. DY Patil Univ. 2015, 8, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, A.; Kuppili, P.P.; Gupta, R.; Deep, R.; Khandelwal, S.K. Prevalence and predictors of family accommodation in obsessive–compulsive disorder in an Indian setting. Indian J. Psychiatry 2020, 62, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauhoff, S. Self-report bias in estimating cross-sectional and treatment effects. Encycl. Qual. Life Well-Being Res. 2014, 11, 5798–5800. [Google Scholar]

- Boutoleau-Bretonnière, C.; Pouclet-Courtemanche, H.; Gillet, A.; Bernard, A.; Deruet, A.L.; Gouraud, I.; Lamy, E.; Mazoué, A.; Rocher, L.; Bretonnière, C.; et al. Impact of confinement on the burden of caregivers of patients with the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease during the COVID-19 crisis in France. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. Extra 2020, 10, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | Participants with OCD n (%) | Caregivers n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 20- | 30 (30.0%) | 19 (19.0%) |

| 30–40 | 49 (49.0%) | 37(37.0%) | |

| >40 | 21 (21.0%) | 44 (44.0%) | |

| Sex | Male | 53 (53.0%) | 31(31.0%) |

| Female | 47 (47.0%) | 69 (69.0%) | |

| Living arrangements | Rural: live with the care recipient | 40 (40.0%) | |

| Rural: do not live with the care recipient but live in the same geographic area | 0.00 | ||

| Urban: live with the care recipient | 3 (3.0%) | ||

| Urban: do not live with the care recipient but live in the same geographic area | 57 (57.0%) | ||

| Social status | Single | 27 (27.0%) | 8 (8.0%) |

| Married | 54 (54.0%) | 83 (83.0%) | |

| Divorced | 13 (13.0%) | 3 (3.0%) | |

| Widow | 6 (6.0%) | 6 (6.0%) | |

| Education level | Illiterate | 8 (8.0%) | 8 (8.0%) |

| Elementary | 10 (10.0%) | 6 (6.0%) | |

| High school | 52 (52.0%) | 44 (44.0%) | |

| University | 30 (30.0%) | 42 (42.0%) | |

| Work status | Working | 39 (39.0%) | 70 (70.0%) |

| Not working | 61(61.0%) | 30 (30.0%) | |

| Socioeconomic level | Low | 23 (23.0%) | 16 (16.0%) |

| Middle | 65 (65.0%) | 71 (71.0%) | |

| High | 12 (12.0%) | 13 (13.0%) | |

| Kinship | Mothers | 26 (26.0%) | |

| Brother/sister | 25 (25.0%) | ||

| Spouse | 46 (46.0%) | ||

| Fathers | 3 (3.0%) | ||

| Variables | Obsessive–Compulsive Level of Studied Participants | χ2 | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate n = 24 | Severe n = 33 | Extremely Severe n = 43 | ||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |||

| Burden level of caregivers | ||||||||

| Low burden | 4 | 16.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Moderate burden | 18 | 75.0 | 16 | 48.5 | 22 | 51.2 | 22.6 | 0.0001(S) |

| Severe burden | 2 | 8.3 | 17 | 51.5 | 21 | 48.8 | ||

| Coping level of caregivers | ||||||||

| Moderate | 20 | 83.3 | 30 | 90.9 | 26 | 60.5 | 10.4 | 0.005(S) |

| Low coping | 4 | 16.7 | 3 | 9.1 | 17 | 39.5 | ||

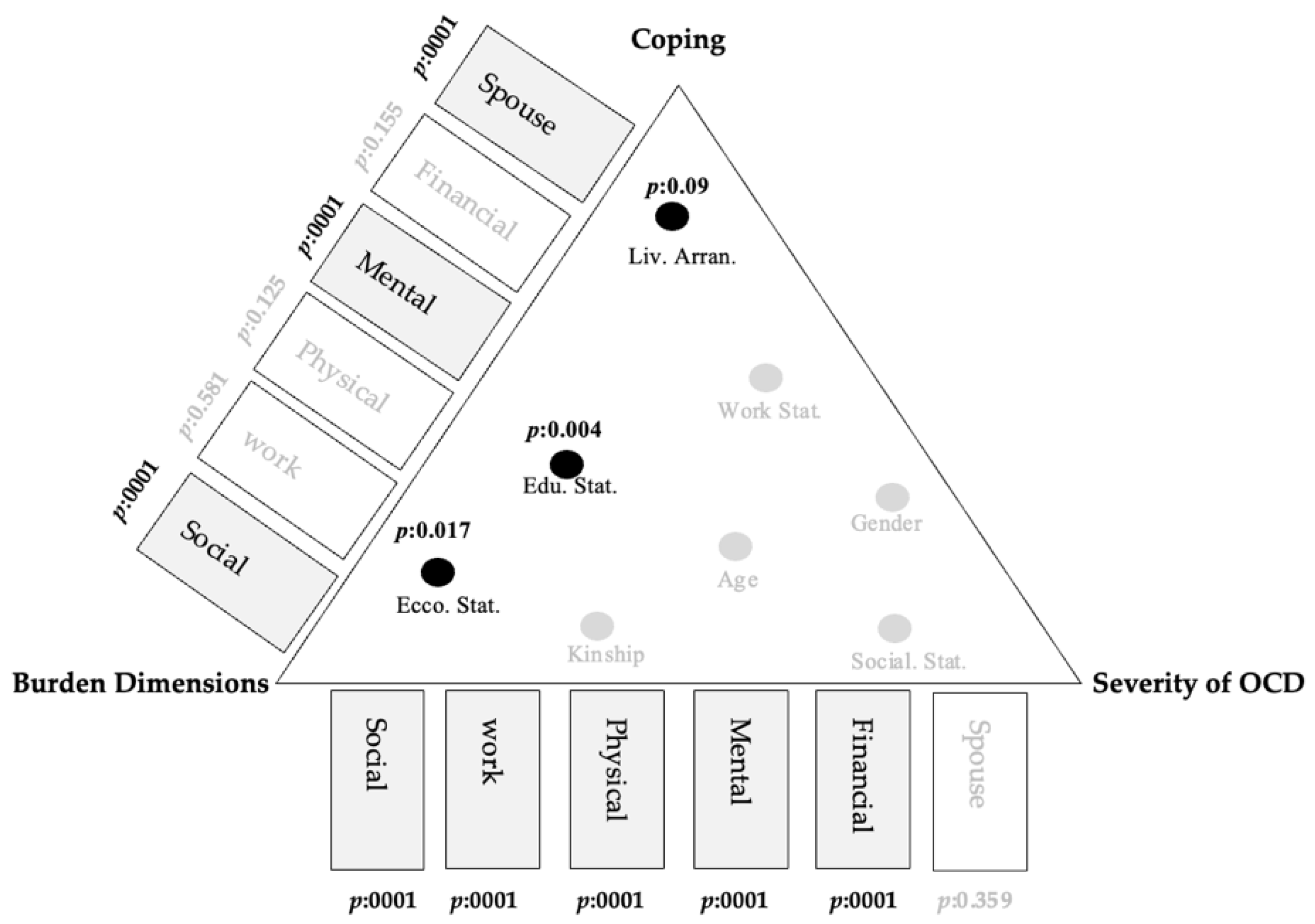

| Burden Dimensions | Obsessive–Compulsive Score of Participants | Coping Score of Participants Caregiver | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (r) | p | (r) | p | |

| Financial aspect (4) | 0.348 ** | 0.0001 | −0.143 | 0.155 |

| Work-related aspect (4) | 0.380 ** | 0.0001 | −0.056 | 0.581 |

| Social and family relationship aspect (12) | 0.347 ** | 0.0001 | −0.495 ** | 0.0001 |

| Mental health aspect (9) | 0.497 ** | 0.0001 | −0.360 ** | 0.0001 |

| Physical health aspect (5) | 0.344 ** | 0.0001 | −0.155 | 0.125 |

| Spouse relationship aspect (6) | 0.093 | 0.359 | −0.399 ** | 0.0001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

El-slamon, M.A.E.-f.A.; Al-Moteri, M.; Plummer, V.; Alkarani, A.S.; Ahmed, M.G. Coping Strategies and Burden Dimensions of Family Caregivers for People Diagnosed with Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder. Healthcare 2022, 10, 451. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10030451

El-slamon MAE-fA, Al-Moteri M, Plummer V, Alkarani AS, Ahmed MG. Coping Strategies and Burden Dimensions of Family Caregivers for People Diagnosed with Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder. Healthcare. 2022; 10(3):451. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10030451

Chicago/Turabian StyleEl-slamon, Marwa Abd El-fatah Ali, Modi Al-Moteri, Virginia Plummer, Ahmed S. Alkarani, and Mona Gamal Ahmed. 2022. "Coping Strategies and Burden Dimensions of Family Caregivers for People Diagnosed with Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder" Healthcare 10, no. 3: 451. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10030451

APA StyleEl-slamon, M. A. E.-f. A., Al-Moteri, M., Plummer, V., Alkarani, A. S., & Ahmed, M. G. (2022). Coping Strategies and Burden Dimensions of Family Caregivers for People Diagnosed with Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder. Healthcare, 10(3), 451. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10030451