Botanical Adjuvants in Oncology: A Review on Natural Compounds in Synergy with Conventional Therapies as Next-Generation Enhancers of Breast Cancer Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology of the Review

3. Review

3.1. Natural Compounds: Classification and Sources

3.2. From Bench to Bedside: Plant-Based Compounds in Breast Cancer Therapy

3.3. Mechanistic Insights, Preclinical Evidence, and Translational Perspectives of Plant-Derived Compounds in Breast Cancer Intervention

3.4. Molecular Pathways Unveiled Through Natural Compounds

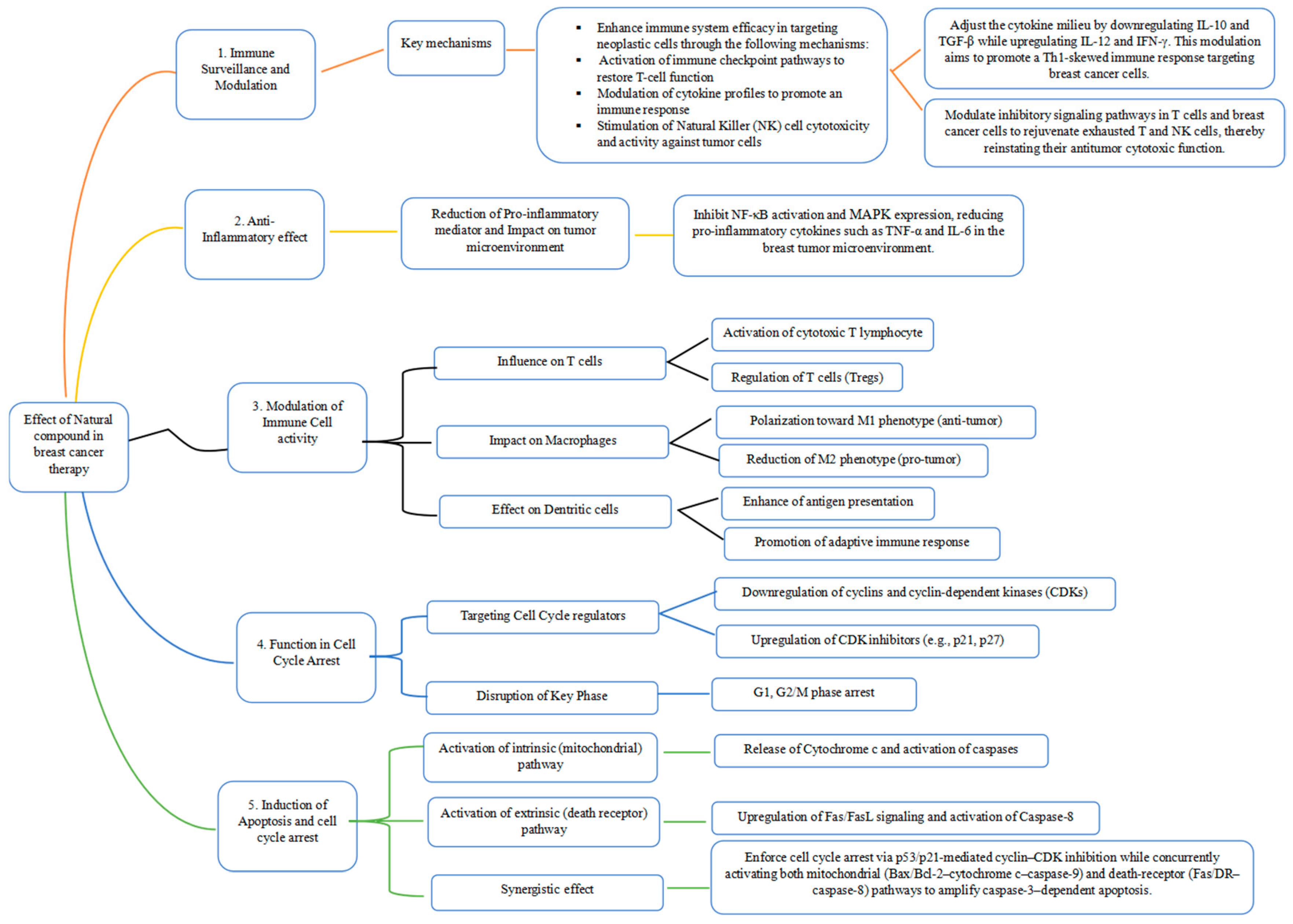

3.4.1. Immune Surveillance and Modulation

3.4.2. Anti-Inflammatory Effects

3.4.3. Modulation of Immune Cell Activity and Function of Natural Compounds in Cell Cycle Arrest for Cancer Management

3.4.4. Induction of Apoptosis and Cell Cycle Arrest

3.4.5. Synergistic Effects of Natural Compounds with Conventional Therapies

4. Advancing Breast Cancer Therapy Through Nanoformulated Natural Compounds

5. Challenges and Future Direction for Natural Compounds in Breast Cancer Therapy

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ghosh, S.; Das, S.K.; Sinha, K.; Ghosh, B.; Sen, K.; Ghosh, N.; Sil, P.C. The Emerging Role of Natural Products in Cancer Treatment. Arch. Toxicol. 2024, 98, 2353–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utpal, B.K.; Bouenni, H.; Zehravi, M.; Sweilam, S.H.; Mortuza, M.R.; Arjun, U.V.N.V.; Shanmugarajan, T.S.; Mahesh, P.G.; Roja, P.; Dodda, R.K.; et al. Exploring Natural Products as Apoptosis Modulators in Cancers: Insights into Natural Product-Based Therapeutic Strategies. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 8189–8214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burguin, A.; Diorio, C.; Durocher, F. Breast Cancer Treatments: Updates and New Challenges. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, B.B.; Tilghman, S.L.; Parker-Lemieux, K.; Payton-Stewart, F. Phytochemicals: Current Strategies for Treating Breast Cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 7471–7478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arzanova, E.; Harvey, N.M. The Epidemiology of Breast Cancer. In Breast Cancer; Exon Publications: Brisbane, Australia, 2022; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Eom, Y.H.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, A.; Song, B.J.; Chae, B.J. Breast Cancer BCL2 as a Subtype-Specific Prognostic Marker for Breast Cancer. J. Breast 2016, 19, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Iqbal, M.O.; Khan, H.; Ahmed, M.M.; Farooq, M.; Aadil, M.M.; Jamaludin, M.I.; Hazafa, A.; Tsai, W.C. A Review of Twenty Years of Research on the Regulation of Signaling Pathways by Natural Products in Breast Cancer. Molecules 2022, 27, 3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque-Bolivar, A.; Pérez-Mora, E.; Villegas, V.E.; Rondón-Lagos, M. Resistance and Overcoming Resistance in Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 2020, 12, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverstein, A.; Sood, R.; Costas-Chavarri, A. Breast Cancer in Africa: Limitations and Opportunities for Application of Genomic Medicine. Int. J. Breast Cancer 2016, 2016, 4792865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-R.; Chang, C.-H.; Hsu, C.-F.; Tsai, M.-J.; Cheng, H.; Leong, M.K.; Sung, P.-J.; Chen, J.-C.; Weng, C.-F. Natural Compounds as Potential Adjuvants to Cancer Therapy: Preclinical Evidence. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 1409–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumber, S.N.; Nchanji, K.N.; Tsoka-Gwegweni, J.M. Breast Cancer among Women in Sub-Saharan Africa: Prevalence and a Situational Analysis. S. Afr. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2017, 9, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Srivastava, A.; Pateriya, A.; Tomar, M.S.; Mishra, A.K.; Shrivastava, A. Metabolic Reprograming Confers Tamoxifen Resistance in Breast Cancer. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2021, 347, 109602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinnel, B.; Singh, S.K.; Oprea-Ilies, G.; Singh, R. Targeted Therapy and Mechanisms of Drug Resistance in Breast Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Peng, C.; Tang, H.; Liu, X.; Peng, F. New Advances in the Research of Resistance to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, T.; Lukong, K.E. Breast Cancer Stem-Like Cells in Drug Resistance: A Review of Mechanisms and Novel Therapeutic Strategies to Overcome Drug Resistance. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 856974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukong, K.E.; Yetunde, O.; Jean, P.K. Breast Cancer in Africa: Prevalence, Treatment Options, Herbal Medicines, and Socioeconomic Determinants. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 166, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljabali, A.A.A.; Obeid, M.A.; Bashatwah, R.M.; Qnais, E.; Gammoh, O.; Alqudah, A.; Mishra, V.; Mishra, Y.; Khan, M.A.; Parvez, S.; et al. Phytochemicals in Cancer Therapy: A Structured Review of Mechanisms, Challenges, and Progress in Personalized Treatment. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, 22, e202402479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, T.; Hakeem, K.R. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants: Healthcare and Industrial Applications; Tariq, A., Khalid, R.H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; ISBN 9783030589752. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Maximizing Potential of Traditional Through Modern Science and Technology; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gaobotse, G.; Venkataraman, S.; Brown, P.D.; Masisi, K.; Kwape, T.E.; Nkwe, D.O.; Rantong, G.; Makhzoum, A. The Use of African Medicinal Plants in Cancer Management. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1122388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omara, T.; Odero, M.P.; Obakiro, S.B. Medicinal Plants Used for Treating Cancer in Kenya: An Ethnopharmacological Overview. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2022, 46, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boța, M.; Vlaia, L.; Jîjie, A.R.; Marcovici, I.; Crişan, F.; Oancea, C.; Dehelean, C.A.; Mateescu, T.; Moacă, E.A. Exploring Synergistic Interactions between Natural Compounds and Conventional Chemotherapeutic Drugs in Preclinical Models of Lung Cancer. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkili, I.; Suluvoy, J.K.; Thathapudi, J.J.; Dey, P.; Srirama, K. Synergistic Strategies for Cancer Treatment: Leveraging Natural Products, Drug Repurposing and Molecular Targets for Integrated Therapy. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2024, 13, 96, Correction in Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2024, 13, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, M.K. Plant-Derived Bioactives: Chemistry and Mode of Action; Springer: Singapore, 2020; ISBN 9789811523618. [Google Scholar]

- Jamiołkowska, A. Natural Compounds as Elicitors of Plant Resistance against Diseases and New Biocontrol Strategies. Agronomy 2020, 10, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, J.; Wang, J.; He, L.; Jin, H.; Kang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, N.; et al. Natural Anti-Cancer Products: Insights from Herbal Medicine. Chin. Med. 2025, 20, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.; Halagali, P.; Majumder, A.; Sharma, V.; Pathak, R. Natural Compounds Targeting Signaling Pathways in Breast Cancer Therapy. Afr. J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 6, 5431–5479. [Google Scholar]

- Egbuna, C.; Hassan, S. Dietary Phytochemicals: A Source of Novel Bioactive Compounds for the Treatment of Obesity, Cancer and Diabetes; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; ISBN 9783030729998. [Google Scholar]

- Almilaibary, A. Phyto-Therapeutics as Anti-Cancer Agents in Breast Cancer: Pathway Targeting and Mechanistic Elucidation. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 31, 103935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swamy, M.K.; Akhtar, M.S. Natural Bio-Active Compounds: Chemistry, Pharmacology and Health Care Practices; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 2, ISBN 9789811372056. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhari, A.S.; Mandave, P.C.; Deshpande, M.; Ranjekar, P.; Prakash, O. Phytochemicals in Cancer Treatment: From Preclinical Studies to Clinical Practice. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 10, 1614, Correction in Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Buelga, C.; Feliciano, A.S.; McPhee, D.J. Flavonoids: From Structure to Health Issues. Molecules 2017, 22, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, M.C.; Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Silva, A.M.S. Plant Flavonoids: Chemical Characteristics and Biological Activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, S.A.; Dar, A.; Hamid, L.; Nisar, N.; Malik, J.A.; Ali, T.; Bader, G.N. Flavonoids as Promising Molecules in the Cancer Therapy: An Insight. Curr. Res. Pharmacol. Drug Discov. 2024, 6, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.G.; Cassani, L.; Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Otero, P.; Mansoor, S.; Echave, J.; Xiao, J.; Simal-Gándara, J.; Prieto, M.A. Plant Alkaloids: Production, Extraction, and Potential Therapeutic Properties. In Natural Secondary Metabolites: From Nature, Through Science, to Industry; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 157–200. ISBN 9783031185878. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, P.K.; Vdhrodiya, R. 1.0.0: Alkaloids: Classification, Properties, Physicochemical and Pharmacological Activities. Int. J. Res. Anal. Rev. 2022, 9, 655–665. [Google Scholar]

- Leclerc, A.; Fournier, P. The Role of Alkaloids in Natural Products Chemistry. Int. J. Herb. Med. 2024, 12, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Déclaire Mabou, F.; Belinda, I.; Yossa, N. TERPENES: Structural Classification and Biological Activities. IOSR J. Pharm. Biol. Sci. (IOSR-JPBS) 2021, 16, 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Map: Organic Chemistry (Wade). Available online: https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Organic_Chemistry/Map%3A_Organic_Chemistry_(Wade)_Complete_and_Semesters_I_and_II/Map%3A_Organic_Chemistry_(Wade) (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- Jiang, M.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Zhu, D.; Liu, L. Structural Diversity and Bioactivities of Marine Fungal Terpenoids (2020–2024). Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Tao, H. Enhancing Structural Diversity of Terpenoids by Multisubstrate Terpene Synthases. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2024, 20, 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juang, Y.P.; Liang, P.H. Biological and Pharmacological Effects of Synthetic Saponins. Molecules 2020, 25, 4974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsena, Y.P.; Phosanam, A.; Stockmann, R. Perspectives on Saponins: Food Functionality and Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, R.; Rashidinejad, A. Lignans. In Handbook of Food Bioactive Ingredients; Jafari, S.M., Rashidinejad, A., Simal-Gandara, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–26. ISBN 978-3-030-81404-5. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhija, M.; Joshi, B.C.; Bairy, P.S.; Bhargava, A.; Sah, A.N. Lignans: A Versatile Source of Anticancer Drugs. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2022, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, W.Y.; Kim, M.Y.; Cho, J.Y. Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, Anti-Menopausal, and Anti-Cancer Effects of Lignans and Their Metabolites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pezzani, R.; Salehi, B.; Vitalini, S.; Iriti, M.; Zuñiga, F.A.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Martorell, M.; Martins, N. Synergistic Effects of Plant Derivatives and Conventional Chemotherapeutic Agents: An Update on the Cancer Perspective. Medicina 2019, 55, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangra, K.; Kakkar, S.; Mittal, V.; Kumar, V.; Aggarwal, N.; Chopra, H.; Malik, T.; Garg, V. Incredible Use of Plant-Derived Bioactives as Anticancer Agents. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 1721–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehelean, C.A.; Marcovici, I.; Soica, C.; Mioc, M.; Coricovac, D.; Iurciuc, S.; Cretu, O.M.; Pinzaru, I. Plant-Derived Anticancer Compounds as New Perspectives in Drug Discovery and Alternative Therapy. Molecules 2021, 26, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Luo, J.; Cai, Z. Biosynthesis and Regulatory Mechanisms of Plant Flavonoids: A Review. Plants 2025, 14, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandavar, H.; Afshari Babazad, M. Secondary Metabolites: Alkaloids and Flavonoids in Medicinal Plants. In Herbs and Spices-New Advances; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lavate, S.S.; Jakune, V.L.; Sable, V.U.; Mhetre, R.M. Pharmacological Activity of Alkaloids. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 2024, 5, 6167–6175. [Google Scholar]

- Kurek, J. Introductory Chapter: Alkaloids—Their Importance in Nature and for Human Life. In Alkaloids—Their Importance in Nature and Human Life; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yahfoufi, N.; Alsadi, N.; Jambi, M.; Matar, C. The Immunomodulatory and Anti-Inflammatory Role of Polyphenols. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Liu, Z.; Lin, M.; Gao, N.; Wang, X. Polyphenols in Health and Food Processing: Antibacterial, Anti-Inflammatory, and Antioxidant Insights. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1456730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avtanski, D.; Poretsky, L. Phyto-Polyphenols as Potential Inhibitors of Breast Cancer Metastasis. Mol. Med. 2018, 24, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Ki, M.R.; Min, K.H.; Pack, S.P. Advanced Delivery System of Polyphenols for Effective Cancer Prevention and Therapy. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudrapal, M.; Khairnar, S.J.; Khan, J.; Dukhyil, A.B.; Ansari, M.A.; Alomary, M.N.; Alshabrmi, F.M.; Palai, S.; Deb, P.K.; Devi, R. Dietary Polyphenols and Their Role in Oxidative Stress-Induced Human Diseases: Insights into Protective Effects, Antioxidant Potentials and Mechanism(s) of Action. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 806470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagos, D. Antioxidant Activity of Polyphenolic Plant Extracts. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asma, S.T.; Acaroz, U.; Imre, K.; Morar, A.; Shah, S.R.A.; Hussain, S.Z.; Arslan-Acaroz, D.; Demirbas, H.; Hajrulai-Musliu, Z.; Istanbullugil, F.R.; et al. Natural Products/Bioactive Compounds as a Source of Anticancer Drugs. Cancers 2022, 14, 6203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizanur Rahaman, M.; Islam, M.T. Anticancer Activity of Plant Derived Compounds: A Literature Based Review. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 7, 1917. [Google Scholar]

- Padamsingh Malla, D.; Kamble, S. Anticancer Potential of Plant-Derived Compounds: A Comprehensive. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 3, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telang, N.T. Natural Products as Drug Candidates for Breast Cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2023, 26, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, E. Top 100 Cited Classic Articles in Breast Cancer Research. Eur. J. Breast Health 2017, 13, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricardo Guimarães, A.; Albuquerque dos Santos, S.; Nalone Andrade, L.; Severino, P.; Andrade Carvalho, A. Natural Products as Treatment against Cancer: A Historical and Current Vision. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 4, 1562. [Google Scholar]

- Gahtori, R.; Tripathi, A.H.; Kumari, A.; Negi, N.; Paliwal, A.; Tripathi, P.; Joshi, P.; Rai, R.C.; Upadhyay, S.K. Anticancer Plant-Derivatives: Deciphering Their Oncopreventive and Therapeutic Potential in Molecular Terms. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla, R.K.; Bishayee, A. Anticancer Drug Discovery Based on Natural Products: From Computational Approaches to Clinical Studies. Cancers 2025, 17, 2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoumeh Kaveh, Z.; Sajjad, A.; Abolfazl, D.; Sepideh, K.; Behnaz Sadeghzadeh, O.; Mirahmad, M.; Morteza, A.; Rana, J.-E. Paclitaxel for Breast Cancer Therapy: A Review on Effective Drug Combination Modalities and Nano Drug Delivery Platforms. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 95, 105567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Stecklein, S.R.; Yoder, R.; Staley, J.M.; Schwensen, K.; O’Dea, A.; Nye, L.; Satelli, D.; Crane, G.; Madan, R.; et al. Clinical and Biomarker Findings of Neoadjuvant Pembrolizumab and Carboplatin Plus Docetaxel in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer NeoPACT Phase 2 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2024, 10, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ya-Jung, W.; Jung-Jung, T.; Ming-Wei, L.; Ling-Ming, T.; Chih-Jung, W. Revealing Symptom Profiles: A Pre-Post Analysis of Docetaxel Therapy in Individuals with Breast Cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2024, 68, 102451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awajan, D.; Abu-Humaidan, A.H.A.; Talib, W.H. Study of the Antitumor Activity of the Combination Baicalin and Epigallocatechin Gallate in a Murine Model of Vincristineresistant Breast Cancer. Pharmacia 2024, 71, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.K.; Kim, H.S.I.K.; Yoon, S. Co-Treatment with Aripiprazole and Vincristine Sensitizes P-Glycoprotein-Overexpressing Drug-Resistant MCF-7/ADR Breast Cancer Cells. Anticancer Res 2024, 44, 1051–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, J.C.; Munster, P.; Northfelt, D.W.; Han, H.S.; Ma, C.; Maxwell, F.; Wang, T.; Belanger, B.; Zhang, B.; Moore, Y.; et al. Phase I Study of Liposomal Irinotecan in Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer: Findings from the Expansion Phase. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 185, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandu, H.; Aluzaite, K.; Fogh, L.; Thrane, S.W.; Noer, J.B.; Proszek, J.; Do, K.N.; Hansen, S.N.; Damsgaard, B.; Nielsen, S.L.; et al. Molecular Characterization of Irinotecan (SN-38) Resistant Human Breast Cancer Cell Lines. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augustine, M.; Copson, E. Trastuzumab Emtansine for Residual Invasive HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. In 50 Landmark Papers: Every Breast Surgeon Should Know; CRC Press: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- von Minckwitz, G.; Huang, C.-S.; Mano, M.S.; Loibl, S.; Mamounas, E.P.; Untch, M.; Wolmark, N.; Rastogi, P.; Schneeweiss, A.; Redondo, A.; et al. Trastuzumab Emtansine for Residual Invasive HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, J.; Kim, S.-B.; Chung, W.-P.; Im, S.-A.; Park, Y.H.; Hegg, R.; Kim, M.H.; Tseng, L.-M.; Petry, V.; Chung, C.-F.; et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan versus Trastuzumab Emtansine for Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1143–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.-Y.; Fang, Z.-R.; Zhang, H.-P.; Xu, J.-Y.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Chen, K.-Y.; Wang, W.; Jiang, X.; Wang, X.-J. Ginsenosides: Changing the Basic Hallmarks of Cancer Cells to Achieve the Purpose of Treating Breast Cancer. Chin. Med. 2023, 18, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Wang, J.; Lu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, L.; Ge, A.; Fan, H.; Liu, L. Updating the Therapeutic Role of Ginsenosides in Breast Cancer: A Bibliometrics Study to an in-Depth Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1226629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakhjavani, M.; Smith, E.; Palethorpe, H.M.; Tomita, Y.; Yeo, K.; Price, T.J.; Townsend, A.R.; Hardingham, J.E. Anti-Cancer Effects of an Optimised Combination of Ginsenoside Rg3 Epimers on Triple Negative Breast Cancer Models. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhjavani, M.; Smith, E.; Yeo, K.; Tomita, Y.; Price, T.J.; Yool, A.; Townsend, A.R.; Hardingham, J.E. Differential Antiangiogenic and Anticancer Activities of the Active Metabolites of Ginsenoside Rg3. J. Ginseng Res. 2024, 48, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhjavani, M.; Smith, E.; Yeo, K.; Palethorpe, H.M.; Tomita, Y.; Price, T.J.; Townsend, A.R.; Hardingham, J.E. Anti-Angiogenic Properties of Ginsenoside Rg3 Epimers: In Vitro Assessment of Single and Combination Treatments. Cancers 2021, 13, 2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Stojanović-Radić, Z.; Matejić, J.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Anil Kumar, N.V.; Martins, N.; Sharifi-Rad, J. The Therapeutic Potential of Curcumin: A Review of Clinical Trials. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 163, 527–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoi, V.; Galani, V.; Lianos, G.D.; Voulgaris, S.; Kyritsis, A.P.; Alexiou, G.A. The Role of Curcumin in Cancer Treatment. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, B.; Penroz, S.; Torres, K.; Simón, L. Curcumin Administration Routes in Breast Cancer Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mundekkad, D.; Cho, W.C. Applications of Curcumin and Its Nanoforms in the Treatment of Cancer. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, A.Y.; Motechin, R.A.; Wiesenfeld, M.Y.; Holz, M.K. The Therapeutic Potential of Resveratrol: A Review of Clinical Trials. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2017, 1, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristina, A.; Caterina, B.; Kathleen, W.; Rita, C.; Marzia, B.; Mauro, M.; Albana, H.; Augusto, A.; Manuela, I.; Cristina, M. Resveratrol Fuels HER2 and ERα-Positive Breast Cancer Behaving as proteasome Inhibitor. Aging 2017, 9, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behroozaghdam, M.; Dehghani, M.; Zabolian, A.; Kamali, D.; Javanshir, S.; Hasani Sadi, F.; Hashemi, M.; Tabari, T.; Rashidi, M.; Mirzaei, S.; et al. Resveratrol in Breast Cancer Treatment: From Cellular Effects to Molecular Mechanisms of Action. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leo, C.P.; Hentschel, B.; Szucs, T.D.; Leo, C. FDA and EMA Approvals of New Breast Cancer Drugs—A Comparative Regulatory Analysis. Cancers 2020, 12, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorbani-Abdi-Saedabad, A.; Hanafi-Bojd, M.Y.; Parsamanesh, N.; Tayarani-Najaran, Z.; Mollaei, H.; Hoshyar, R. Anticancer and Apoptotic Activities of Parthenolide in Combination with Epirubicin in Mda-Mb-468 Breast Cancer Cells. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 5807–5815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Lu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Lv, H. Indocyanine Green-Parthenolide Thermosensitive Liposome Combination Treatment for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 3193–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Yao, X.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, H.; Tang, J.; Yang, W. Dihydroartemisinin-Loaded Magnetic Nanoparticles for Enhanced Chemodynamic Therapy. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Soto-Gamez, A.; Nijdam, F.; Setroikromo, R.; Quax, W.J. Dihydroartemisinin-Transferrin Adducts Enhance TRAIL-Induced Apoptosis in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer in a P53-Independent and ROS-Dependent Manner. Front. Oncol. 2022, 11, 789336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, A.; Huang, W.; Chen, S.; Han, F.; Wang, L. Dihydroartemisinin Induces Pyroptosis by Promoting the AIM2/Caspase-3/DFNA5 Axis in Breast Cancer Cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2021, 340, 109434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodali, N.; Madu, C.O.; Lu, Y. Phytochemicals in Breast Cancer Prevention and Therapy: Mechanisms, Efficacy, and Future Prospects. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, S.K.; Sharma, P.; Kumar, M.; Bhat, B.; Das, M. Preclinical and Clinical Studies on the Efficacy of Phytochemicals in Cancer Treatment. In Nano-Formulation of Dietary Phytochemicals for Cancer Management; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2024; pp. 211–239. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.; Verron, E.; Rohanizadeh, R. Molecular Mechanisms of Anti-Metastatic Activity of Curcumin. Anticancer Res. 2016, 36, 5639–5648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Xu, Y.; Meng, L.; Huang, L.; Sun, H. Curcumin Inhibits Proliferation and Promotes Apoptosis of Breast Cancer Cells. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 16, 1266–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameer, S.F.; Mohamed, M.Y.; Elzubair, Q.A.; Sharif, E.A.M.; Ibrahim, W.N. Curcumin as a Novel Therapeutic Candidate for Cancer: Can This Natural Compound Revolutionize Cancer Treatment? Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1438040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, E.; Kotiya, A.; Khan, A.; Bhuyan, R.; Raza, S.T.; Misra, A.; Mahdi, A.A. The Combination of Curcumin and Doxorubicin on Targeting PI3K/AKT/MTOR Signaling Pathway: An in Vitro and Molecular Docking Study for Inhibiting the Survival of MDA-MB-231. Silico Pharmacol. 2024, 12, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoi, V.; Kyritsis, A.P.; Galani, V.; Lazari, D.; Sioka, C.; Voulgaris, S.; Alexiou, G.A. The Role of Curcumin in Cancer: A Focus on the PI3K/Akt Pathway. Cancers 2024, 16, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boroughani, M.; Moaveni, A.K.; Hatami, P.; Mansoob Abasi, N.; Seyedoshohadaei, S.A.; Pooladi, A.; Moradi, Y.; Rahimi Darehbagh, R. Nanocurcumin in Cancer Treatment: A Comprehensive Systematic Review. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcelos, K.A.; Mendonça, C.R.; Noll, M.; Botelho, A.F.; Francischini, C.R.D.; Silva, M.A.M. Antitumor Properties of Curcumin in Breast Cancer Based on Preclinical Studies: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2022, 14, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givi, T.; Mohajerani, F.; Tehrankhah, Z.M.; Karimi Taheri, M.; Amirahmadi, M.; Babashah, S.; Sadeghizadeh, M. Nano-Curcumin Enhances the Sensitivity of Tamoxifen-Resistant Breast Cancer Cells via the Cyclin D1-DILA1 Axis and the PI3K/AKT/MTOR Pathway Downregulation. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0335165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Mandal, A.K.A. Role of Epigallocatechin-3- Gallate in the Regulation of Known and Novel MicroRNAs in Breast Carcinoma Cells. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 995046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talib, W.H.; Awajan, D.; Alqudah, A.; Alsawwaf, R.; Althunibat, R.; Abu AlRoos, M.; Al Safadi, A.; Abu Asab, S.; Hadi, R.W.; Al Kury, L.T. Targeting Cancer Hallmarks with Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG): Mechanistic Basis and Therapeutic Targets. Molecules 2024, 29, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Cao, D.; Sun, Y.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Cao, X. The Roles of Epigallocatechin Gallate in the Tumor Microenvironment, Metabolic Reprogramming, and Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1331641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, V.K.; Mishra, B.; Mahapatra, S.; Swain, B.; Malhotra, D.; Saha, S.; Khanra, S.; Mishra, P.; Majhi, S.; Kumari, K.; et al. Molecular Insights on Signaling Cascades in Breast Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers 2025, 17, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, V. EGCG Prophylaxis Reduced Incidence, Severity of Radiation-Induced Dermatitis in Breast Cancer. 2022. Available online: https://www.oncologynurseadvisor.com/news/breast-cancer-epigallocatechin-gallate-prophylaxis-reduced-incidence-severity/ (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Zhao, H.; Zhu, W.; Jia, L.; Sun, X.; Chen, G.; Zhao, X.; Li, X.; Meng, X.; Kong, L.; Xing, L.; et al. Phase I Study of Topical Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG) in Patients with Breast Cancer Receiving Adjuvant Radiotherapy. Br. J. Radiol. 2016, 89, 20150665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.H.; Mao, J.W.; Tan, X.L. Research Progress on the Source, Production, and Anti-Cancer Mechanisms of Paclitaxel. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2020, 18, 890–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisari, M. Investigation of the Effect of Paclitaxel on MCF-7 on Breast Cancer Cell Line. J. US China Med. Sci. 2020, 17, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Samaan, T.M.; Samec, M.; Liskova, A.; Kubatka, P.; Büsselberg, D. Paclitaxel’s Mechanistic and Clinical Effects on Breast Cancer. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, T.T.; Shou, K.J.; Reinhardt, B.J.; Kigelman, O.F.; Greenfield, K.M. Paclitaxel Drug-Drug Interactions in the Military Health System. Fed. Pract. 2024, 41, S70–S82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmoghadasiyan, B.; Tavakkoli, F.; Beram, F.M.; Badmasti, F.; Mirzaie, A.; Kazempour, R.; Rahimi, S.; Larijani, S.F.; Hejabi, F.; Sedaghatnia, K. Nanosized Paclitaxel-Loaded Niosomes: Formulation, in Vitro Cytotoxicity, and Apoptosis Gene Expression in Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 3597–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asnaashari, S.; Amjad, E.; Sokouti, B. Synergistic Effects of Flavonoids and Paclitaxel in Cancer Treatment: A Systematic Review. Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Sun, L.; Gai, J.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, S. Exploring the Resistance Mechanism of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer to Paclitaxel through the ScRNA-Seq Analysis. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alalawy, A.I. Key Genes and Molecular Mechanisms Related to Paclitaxel Resistance. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abouzeid, H.A.; Kassem, L.; Liu, X.; Abuelhana, A. Paclitaxel Resistance in Breast Cancer: Current Challenges and Recent Advanced Therapeutic Strategies. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2025, 43, 100918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roshanazadeh, M.; Rezaei, H.B.; Rashidi, M. Quercetin Enhances the Suppressive Effects of Doxorubicin on the Migration of MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Cell Line. Int. J. Cancer Manag. 2021, 14, e119049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, D.; Yan, X.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Y.; Cao, J.; Ma, R.; Hong, S.; Ma, M. To Explore Immune Synergistic Function of Quercetin in Inhibiting Breast Cancer Cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.M.; Deng, X.T.; Zhou, J.; Li, Q.P.; Ge, X.X.; Miao, L. Pharmacological Basis and New Insights of Quercetin Action in Respect to Its Anti-Cancer Effects. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 121, 109604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Gao, D.; Wang, T.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S. From Nature to Clinic: Quercetin’s Role in Breast Cancer Immunomodulation. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1483459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-F.; Lin, Y.-Q.; Park, J.M.; Chen, Y.-C.; Hung, S.-W.; Chiu, C.-C.; Chang, C.-F. The Novel Camptothecin Derivative, CPT211, Induces Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in Models of Human Breast Cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 128, 110309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, E.; Rojas, V.; Ferreira, J. Determining the Effect of siRNA-Egr-1 and Camptothecin on Growth and Chemosensitivity of Breast Cancer Cells. Adv. Res. Biol. Sci. 2023, 4, 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Vishnupriya, N.; Jayaraman, S.; Veeraraghavan, V.P. Camptothecin Anti-Cancer Activity Against Breast Cancer Cells (MDA MB-231) Targeting the Gene Expression of Wnt/Beta-Catenin Pathway-An In Silico and In Vitro Approach. Texila Int. J. Public Health 2025, 25, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorai, M.; Das, N.; Mishra, T.; Mane, A.B.; Gadekar, V.S.; Saha, S.C.; Prasanth Dorairaj, A. Advances in Camptothecin Nanomedicine: Enhancing Targeted Breast-Cancer Therapeutics Using Innovative Drug Delivery Systems. Nucleus 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesauro, C.; Simonsen, A.K.; Andersen, M.B.; Petersen, K.W.; Kristoffersen, E.L.; Algreen, L.; Hansen, N.Y.; Andersen, A.B.; Jakobsen, A.K.; Stougaard, M.; et al. Topoisomerase i Activity and Sensitivity to Camptothecin in Breast Cancer-Derived Cells: A Comparative Study. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, A.; Carmo, F.; Pinto, S.; Andrade, N.; Martel, F. The Anti-Proliferative Effect of β-Carotene against a Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cell Line Is Cancer Cell-Specific and JNK-Dependent. PharmaNutrition 2022, 22, 100320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehnavi, M.K.; Ebrahimpour-Koujan, S.; Lotfi, K.; Azadbakht, L. The Association between Circulating Carotenoids and Risk of Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Dose–Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, A.; Basirnejad, M.; Shahbazi, S.; Bolhassani, A. Carotenoids: Biochemistry, Pharmacology and Treatment. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1290–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peraita-Costa, I.; Carrillo Garcia, P.; Morales-Suárez-Varela, M. Is There an Association between β-Carotene and Breast Cancer? A Systematic Review on Breast Cancer Risk. Nutr. Cancer 2022, 74, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumeeruddy, M.Z.; Mahomoodally, M.F. Combating Breast Cancer Using Combination Therapy with 3 Phytochemicals: Piperine, Sulforaphane, and Thymoquinone. Cancer 2019, 125, 1600–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnett, J.P.; Lim, G.; Li, Y.; Shah, R.B.; Lim, R.; Paholak, H.J.; McDermott, S.P.; Sun, L.; Tsume, Y.; Bai, S.; et al. Sulforaphane Enhances the Anticancer Activity of Taxanes against Triple Negative Breast Cancer by Killing Cancer Stem Cells. Cancer Lett. 2017, 394, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra-Leos, M.Z.; Jordan-Alejandre, E.; Puente-Rivera, J.; Silva-Cázares, M.B. Molecular Pathways Related to Sulforaphane as Adjuvant Treatment: A Nanomedicine Perspective in Breast Cancer. Medicina 2022, 58, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuran, D.; Pogorzelska, A.; Wiktorska, K. Breast Cancer Prevention-Is There a Future for Sulforaphane and Its Analogs? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pogorzelska, A.; Mazur, M.; Świtalska, M.; Wietrzyk, J.; Sigorski, D.; Fronczyk, K.; Wiktorska, K. Anticancer Effect and Safety of Doxorubicin and Nutraceutical Sulforaphane Liposomal Formulation in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) Animal Model. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 161, 114490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangla, B.; Javed, S.; Sultan, M.H.; Kumar, P.; Kohli, K.; Najmi, A.; Alhazmi, H.A.; Al Bratty, M.; Ahsan, W. Sulforaphane: A Review of Its Therapeutic Potentials, Advances in Its Nanodelivery, Recent Patents, and Clinical Trials. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 5440–5458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhazmi, N.; Subahi, A. Impact of Sulforaphane on Breast Cancer Progression and Radiation Therapy Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e78060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, P.P.; Islam, M.A.; Islam, M.S.; Han, A.; Geng, P.; Aziz, M.A.; Mamun, A.A. A Comprehensive Evaluation of the Therapeutic Potential of Silibinin: A Ray of Hope in Cancer Treatment. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1349745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.D.; Mendonca, P.; Kaur, S.; Soliman, K.F.A. Silibinin Anticancer Effects Through the Modulation of the Tumor Immune Microenvironment in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.R.R.; Mittal, P.; Kundu, B.; Singh, A.; Singh, I.K. Silibinin: An Inhibitor for a High-Expressed BCL-2A1/BFL1 Protein, Linked with Poor Prognosis in Breast Cancer. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2024, 42, 12122–12132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, C.; Lu, S.; Qiao, J.; Han, M. The Combinatory Effects of Natural Products and Chemotherapy Drugs and Their Mechanisms in Breast Cancer Treatment. Phytochem. Rev. 2020, 19, 1179–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakudze, N.T.; Sarbadhikary, P.; George, B.P.; Abrahamse, H. Ethnomedicinal Uses, Phytochemistry, and Anticancer Potentials of African Medicinal Fruits: A Comprehensive Review. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B.; Li, J.; Yan, J.L.; Jiang, C.Y.; Qian, L.B.; Pan, J. Resveratrol Contributes to NK Cell-Mediated Breast Cancer Cytotoxicity by Upregulating ULBP2 through MiR-17-5p Downmodulation and Activation of MINK1/JNK/c-Jun Signaling. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1515605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.H.; Wu, C.H.; Tsai, C.C.; Chen, T.Y.; Tsai, K.J.; Hung, C.M.; Hsu, C.Y.; Wu, C.W.; Hsieh, T.H. Effects of Luteolin on Human Breast Cancer Using Gene Expression Array: Inferring Novel Genes. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 2107–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monica, S.J.; Jemima, D.; Daniel, E.L.; Selvaraju, P.; Preetha, M.A.; Rajendran, E.G.M.G. Phytochemicals as Anticancer Agents: Investigating Molecular Pathways from Preclinical Research to Clinical Relevance. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. J. 2025, 13, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yin, L.; Shen, S.; Hou, Y. Inflammation and Cancer: Paradoxical Roles in Tumorigenesis and Implications in Immunotherapies. Genes. Dis. 2023, 10, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, Q.; Inchakalody, V.P.; Bedhiafi, T.; Mestiri, S.; Taib, N.; Uddin, S.; Merhi, M.; Dermime, S. Chronic Inflammation and Cancer; the Two Sides of a Coin. Life Sci. 2024, 338, 122390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hjazi, A.; Mohammed, S.N.; Abosaoda, M.K.; Ahmad, I.; Rekha, M.M.; Kundlas, M.; Ullah, M.I.; Abd, B.; Ray, S.; Nathiya, D. Quercetin as a Multi-Targeted Therapeutic Agent in Breast Cancer: Molecular Targets and Therapeutic Potential. Med. Oncol. 2025, 42, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.S.; Wang, Z.G. Salvianolic Acid B from Salvia Miltiorrhiza Bunge: A Potential Antitumor Agent. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1042745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katary, M.A.; Abdelsayed, R.; Alhashim, A.; Abdelhasib, M.; Elmarakby, A.A. Salvianolic Acid B Slows the Progression of Breast Cancer Cell Growth via Enhancement of Apoptosis and Reduction of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Angiogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; He, W.; Ju, J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y. The Effect of Resveratrol, Curcumin and Quercetin Combination on Immuno-Suppression of Tumor Microenvironment for Breast Tumor-Bearing Mice. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13278, Correction in Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19984. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Smith, W.; Kong, L. Natural Products for Regulating Macrophages M2 Polarization. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 15, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niknejad, A.; Esmaealzadeh, N.; Peyrovinasab, A.; Sirouskabiri, S.; Gholami, M.; Pasha, A.V.K.; Shahri, S.; Büsselberg, D.; Abdolghaffari, A.H. Phytochemicals Alleviate Tumorigenesis by Regulation of M1/M2 Polarization: A Systematic Review of the Current Evidence. Phytother. Res. 2025, 39, 3105–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chengzhi, W.; Yifan, L.; Xiaoqing, Z.; Peimin, L.; Dongdong, L. Research Progress of Natural Products Targeting Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Antitumor Immunity: A Review. Medicine 2024, 103, e40576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidaya, M.; Amos, R.M.; Faith, A.R.; Emmanuel, A.M.; Elingarami, S. A Review on the Status of Breast Cancer Care in Tanzania. Multidiscip. Cancer Investig. 2020, 4, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, M.; Perumal, V.; Somu, P.; Kumar, R.M.S. Phytocompounds as Sustainable Therapeutics for Breast Cancer Treatment: A Comprehensive Review on Isolation and Delivery Strategies. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.-D.; Chen, L.-J.; Xu, X.-Y.; Liu, Y.-J.; Tao, F.; Zhu, M.-H.; Li, C.-Y.; Zhao, D.; Yang, G.-J.; Chen, J. Berberine as a Potential Agent for Breast Cancer Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 993775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.-G.; Huang, S.-Y.; Wu, S.-X.; Zhou, D.-D.; Yang, Z.-J.; Saimaiti, A.; Zhao, C.-N.; Shang, A.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Gan, R.-Y.; et al. Anticancer Effects and Mechanisms of Berberine from Medicinal Herbs: An Update Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Long, Y.; Ni, L.; Yuan, X.; Yu, N.; Wu, R.; Tao, J.; Zhang, Y. Anticancer Effect of Berberine Based on Experimental Animal Models of Various Cancers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Z.; Ma, B.; Pei, X.; Wang, W.; Gong, W. Mechanism of Action of Genistein on Breast Cancer and Differential Effects of Different Age Stages. Pharm. Biol. 2025, 63, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleij, P.; Tabari, M.A.K.; Khandan, M.; Poudineh, M.; Rezaee, A.; Sadreddini, S.; Sanaye, P.M.; Khan, H.; Larsen, D.S.; Daglia, M. Genistein in Focus: Pharmacological Effects and Immune Pathway Modulation in Cancer. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 3557–3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.; Han, H.; Oh, Y.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.-H. Anti-Cancer Effects of Genistein Supplementation and Moderate-Intensity Exercise in High-Fat Diet-Induced Breast Cancer via Regulation of Inflammation and Adipose Tissue Metabolism in Vivo and in Vitro. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2025, 25, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robati, A.K.; Shahsavari, Z.; Amin Vaezi, M.; Safizadeh, B.; Shirian, F.I.; Tavakoli-Yaraki, M. Caffeic Acid Stimulates Breast Cancer Death through Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Formation, Caspase Activation and Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Depletion. Acta Biochim. Iran. 2023, 1, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastidas, H.; Araya-Valdés, G.; Cortés, G.; Jara, J.A.; Catalán, M. Pharmacological Effects of Caffeic Acid and Its Derivatives in Cancer: New Targeted Compounds for the Mitochondria. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2022, 1401, 213–225. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.; Qin, H.-Z.; Li, Z.-Y.; Zhu, H.; Long, L.; Xu, L.-B. Gallic Acid Suppresses the Progression of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer HCC1806 Cells via Modulating PI3K/AKT/EGFR and MAPK Signaling Pathways. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1049117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowska, A.; Markowska, J.; Stanisławiak-Rudowicz, J.; Kozak, K.; Roubinek, O.K.; Jasińska, M. The Role of Ferulic Acid in Selected Malignant Neoplasms. Molecules 2025, 30, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olayiwola, Y.; Gollahon, L. Natural Compounds and Breast Cancer: Chemo-Preventive and Therapeutic Capabilities of Chlorogenic Acid and Cinnamaldehyde. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwakigonja, A.R.; Lushina, N.E.; Mwanga, A. Characterization of Hormonal Receptors and Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-2 in Tissues of Women with Breast Cancer at Muhimbili National Hospital, Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. Infect. Agents Cancer 2017, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabel, A.M. Tumor Markers of Breast Cancer: New Prospectives. J. Oncol. Sci. 2017, 3, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wind, N.S.; Holen, I. Multidrug Resistance in Breast Cancer: From In Vitro Models to Clinical Studies. Int. J. Breast Cancer 2011, 2011, 967419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.V.; Martinez, M.; Stamos, M.J.; Moyer, M.P.; Planutis, K.; Hope, C.; Holcombe, R.F. Results of a Phase I Pilot Clinical Trial Examining the Effect of Plant-Derived Resveratrol and Grape Powder on Wnt Pathway Target Gene Expression in Colonic Mucosa and Colon Cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 2009, 1, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Castelló, A.; Martín, M.; Ruiz, A.; Casas, A.M.; Baena-Cañada, J.M.; Lope, V.; Antolín, S.; Sánchez, P.; Ramos, M.; Antón, A.; et al. Lower Breast Cancer Risk among Women Following the World Cancer Research Fund and American Institute for Cancer Research Lifestyle Recommendations: Epigeicam Case-Control Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamajima, N.; Hirose, K.; Tajima, K.; Rohan, T.; Calle, E.E.; Heath, C.W.; Coates, R.J.; Liff, J.M.; Talamini, R.; Chantarakul, N.; et al. Alcohol, Tobacco and Breast Cancer—Collaborative Reanalysis of Individual Data from 53 Epidemiological Studies, Including 58 515 Women with Breast Cancer and 95 067 Women without the Disease. Br. J. Cancer 2002, 87, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladu, A.F.; Ficai, D.; Ene, A.G.; Ficai, A. Combination Therapy Using Polyphenols: An Efficient Way to Improve Antitumoral Activity and Reduce Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gür, F.M.; Bilgiç, S. Silymarin, an Antioxidant Flavonoid, Protects the Liver from the Toxicity of the Anticancer Drug Paclitaxel. Tissue Cell 2023, 83, 102158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Far, A.H.; Salaheldin, T.A.; Godugu, K.; Darwish, N.H.; Mousa, S.A. Thymoquinone and Its Nanoformulation Attenuate Colorectal and Breast Cancers and Alleviate Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Nanomedicine 2021, 16, 1457–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozhat, Z.; Heydarzadeh, S.; Memariani, Z.; Ahmadi, A. Chemoprotective and Chemosensitizing Effects of Apigenin on Cancer Therapy. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherbakov, A.M.; Andreeva, O.E. Apigenin Inhibits Growth of Breast Cancer Cells: The Role of ERα and HER2/Neu. Acta Naturae 2015, 7, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaz, M.; Sultan, M.T.; Khalid, M.U.; Raza, H.; Imran, M.; Hussain, M.; Al Abdulmonem, W.; Alsagaby, S.A.; Abdelgawad, M.A.; Ghoneim, M.M.; et al. A Comprehensive Review on the Molecular Mechanism of Lycopene in Cancer Therapy. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzocco, S.; Singla, R.K.; Capasso, A. Multifaceted Effects of Lycopene: A Boulevard to the Multitarget-Based Treatment for Cancer. Molecules 2021, 26, 5333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elingarami, S.; Li, X.; He, N. Applications of Nanotechnology, next Generation Sequencing and Microarrays in Biomedical Research. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2013, 13, 4539–4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehelgerdi, M.; Chehelgerdi, M.; Allela, O.Q.B.; Pecho, R.D.C.; Jayasankar, N.; Rao, D.P.; Thamaraikani, T.; Vasanthan, M.; Viktor, P.; Lakshmaiya, N.; et al. Progressing Nanotechnology to Improve Targeted Cancer Treatment: Overcoming Hurdles in Its Clinical Implementation. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadri, S.H.; Riaz, A.; Abid, J.; Shaheen, R.; Nadeem, S.; Ghumman, Z.; Naeem, H. Emerging nanostructure-based strategies for breast cancer therapy: Innovations, challenges, and future directions. Med. Oncol. 2025, 42, 188, Erratum in Med. Oncol. 2025, 42, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Lai, X.; Lin, Z.; Xu, Y.; Fu, Z.; Chen, J.; Wu, X. Innovative Nanodelivery Systems for Targeted Breast Cancer Therapy: Overcoming Drug Delivery Challenges and Exploring Future Perspectives. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 9901–9927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheriyan, B.V.; Nandhini, J.; Devaraji, M. Nanotechnology-Enabled Platforms for Breast Cancer Therapy: Advances in Biomaterials, Drug Delivery, and Theranostics. Biomed. Mater. Devices 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golla, K.; Reddy, P.S.; Bhaskar, C.; Kondapi, A.K. Biocompatibility, Absorption and Safety of Protein Nanoparticle-Based Delivery of Doxorubicin through Oral Administration in Rats. Drug Deliv. 2013, 20, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavda, V.P.; Patel, A.B.; Mistry, K.J.; Suthar, S.F.; Wu, Z.-X.; Chen, Z.-S.; Hou, K. Nano-Drug Delivery Systems Entrapping Natural Bioactive Compounds for Cancer: Recent Progress and Future Challenges. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 867655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqathama, A. Natural Products as Promising Modulators of Breast Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1410300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.W.; Lin, L.G.; Ye, W.C. Techniques for Extraction and Isolation of Natural Products: A Comprehensive Review. Chin. Med. 2018, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahira Banu, K.; Cathrine, L. General Techniques Involved in Phytochemical Analysis. Int. J. Adv. Res. Chem. Sci. (IJARCS) 2015, 2, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevan, N.; Kasar Rahul, P.; Subburaju, T.; Suresh, B. HPTLC Analysis of Withaferine A from a Herbal Extract and Polyherbal Formulations. J. Sep. Sci. 2003, 26, 1707–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmalakshmi, S.; Priyanga, S.; Devaki, K. Phytochemical Screening and Hptlc Fingerprinting Analysis of Ethanolic Extract of Erythrina variegata L. Flowers. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 8, 210–217. [Google Scholar]

- Aleskandarany, M.A.; Rakha, E.A.; Douglas Macmillan, R.; Powe, D.G.; Ellis, I.O.; Green, A.R.; Green, A.R. MIB1/Ki-67 Labelling Index Can Classify Grade 2 Breast Cancer into Two Clinically Distinct Subgroups MIB1/Ki-67 Labelling Index Can Classify Grade 2 Breast Cancer into Two Clinically Distinct Subgroups. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010, 127, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, P.; Khan, M.J. Molecular and Computational Studies on Apoptotic Pathway Regulator, Bcl-2 Gene from Breast Cancer Cell Line MCF-7. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 78, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type of Compound | Nature of Compound | Subclass of Compound | Example Compounds | Example of Plants | Specific Cell Lines & Subtypes Studied | Mechanism of Action | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoids | Class of polyphenolic secondary metabolites found in plants, and commonly consumed in the diets of humans. The general structure of flavonoids is a fifteen-carbon skeleton, containing two benzene rings connected by a three-carbon linking chain. Therefore, they are depicted as C6-C3-C6 compounds. | Flavones, Flavonols, Flavanones, Isoflavones, Anthocyanidins | Quercetin, Kaempferol, Luteolin, Apigenin, Genistein, Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), Silibinin, Biochanin A, Icaritin, Hesperetin | Commonly found in fruits, vegetables, teas, and herbs such as Green tea, Citrus fruits, Cereals, and legumes | MCF-7 (ER/PR +), MDA-MB-231 (TNBC), T-47D, SK-BR-3 (HER2+) | Induce apoptosis by activating intrinsic mitochondrial cascades and inhibit cell proliferation through suppression of PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways. block angiogenesis and metastasis through downregulation pathway, offering chemopreventive effects and acting adjunctively with chemotherapy in both early- and late-stage treatment. | [24,25,32,33,50] |

| Alkaloids | Lager cluster of organic secondary metabolites that contain a nitrogen atom and have diverse and important pharmaceutical effect. | Piperidine, Quinoline, Indole, Isoquinoline, Tropan | Vincristine, Vinblastine, Camptothecin, Topotecan, Irinotecan, Berberine, Noscapine, Oxymatrine, Artemisinin | Primarily plant-derived like Madagascar periwinkle Black pepper (Piper nigrum), long pepper (Piper longum) | MDA-MB-231 (TNBC), MCF-7 (ER/PR+), MCF-10A (normal) | Synergistically inhibit STAT3 phosphorylation & induce apoptosis. Activate caspase-8/caspase-9, modulate Bcl-2/Bax. Inhibit microtubule polymerization | [36,37,51,52,53] |

| Terpenoids | Diverse, lipophilic compounds derived from isoprene units; variable structures | Monoterpenoids, Sesquiterpenoids, Diterpenoids, Tetraterpenoids | Andrographolide, Paeoniflorin, Tanshinone IIA, Celastrol, Lycopene | Widely distributed among plants (and some marine organisms) Pacific yew (source of paclitaxel), Algae, mushrooms and lichens | MCF-7 (ER/PR+), MDA-MB-231 (TNBC), MDA-MB-468 (TNBC), 4T1 (murine TNBC) | Inhibit PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway (e.g., paeoniflorin, Tanshinone IIA). Modulate MAPK/ERK, Bax/Bcl-2/caspase-3, NF-κB/EMT pathways. Induce autophagy (e.g., artemisinin, oridonin). | [38,39,40,41] |

| Saponins | Secondary metabolites that are heat-stable, amphiphilic. Glycosides comprising a sugar portion linked to a triterpene or steroid aglycone | Triterpenoid saponins, Steroid saponins | Saikosaponin-A, Dioscin, α-Hederin, Ginsenosides | Ginseng, Quinoa, and Fenugreek | MDA-MB-231 (TNBC), MCF-7 (ER/PR+) | Promote apoptosis, inhibit angiogenesis, modulate the immune system, and improve the efficacy of chemotherapeutic agents; evaluated in both clinical settings and preclinical models for synergistic effects. | [24,42,43] |

| Lignans | Polyphenolic substances with phytoestrogenic and antioxidant properties | Dibenzylbutane, Dibenzylbutyrolactone, Furanofuran | Secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG), Enterolactone (ENL), Macelignan | Mainly sourced from high-fiber plants, seeds, and whole grains like Flaxseed and Sesame seeds | MDA-MB-231 (TNBC), MCF-7 (ER/PR+), T-47D (ER/PR+) | Modulate estrogen metabolism; induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis; particularly beneficial in hormone-responsive breast cancer treatment across both preclinical and clinical phases | [44,45,46] |

| Polyphenols | Broad class featuring multiple phenol groups; includes both flavonoids and non-flavonoids with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory actions | Phenolic acids, Stilbenes, Tannins | Curcumin, Ellagic acid, Gallic acid, Resveratrol (also a stilbene), Chlorogenic acid, Caffeic acid, Ursolic acid, | Grapes, Berries, Green tea, Turmeric | MCF-7 (ER/PR+), MDA-MB-231 (TNBC), BT-474 (HER2+) | Target cellular signaling pathways to inhibit carcinogenesis, promote apoptosis, and reduce oxidative stress; deployed as chemopreventive agents and in adjunct therapy in both early and advanced stages. | [54,55,56,57,58,59] |

| Drug (Generic) | Source Plant/Origin | Cancer Type | Mechanism of Action | Treatment Stage | Regulatory Organization | Ongoing Trials | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paclitaxel | Bark of Taxus brevifolia (Pacific yew) | Breast First-line for multiple subtypes (e.g., TNBC, HER2+) | Microtubule stabilization → mitotic arrest, apoptosis | Approved drug (first-line/metastatic Breast Cancer) | FDA, EMA | Nano-formulation strategies ongoing | [24,68] |

| Docetaxel | Needles of Taxus baccata (European yew) | Breast (First-line and metastatic breast cancer) | Microtubule stabilization → mitotic arrest | Approved drug | FDA, EMA | Combination chemotherapy regimens | [69,70] |

| Vincristine/Vinblastine | Leaves of Catharanthus roseus (Madagascar periwinkle) | Breast | Tubulin polymerization inhibition | Approved drug | FDA | New combination regimens ongoing | [71,72] |

| Topotecan/Irinotecan | Bark of Camptotheca acuminata (happy tree) | Investigational in breast | Topoisomerase I inhibition → DNA breaks, apoptosis | Approved for other cancers; off-label in BCD | FDA, EMA | TNBC trials underway | [73,74] |

| Trastuzuma emtansine (T-DM1) | Maytansinoid (cytotoxin) from Maytenus ovatus | HER2+ metastatic breast cancer | HER2-targeted microtubule disruption | Approved drug | FDA, EMA | ADC combination trials | [75,76,77] |

| Ginsenoside Rg3 | Roots/leaves of Panax ginseng | Triple-negative breast cancer | Inhibits angiogenesis, glycolysis; reverses resistance | Approved in China; Still under clinical trials (TNBC) | China NMPA | Phase II/III Rg3 + capecitabine | [78,79] |

| SRg3 + RRg3 Epimers | Derived from Panax spp. | Metastatic breast cancer | Stemness, EMT, VEGFR2, AQP 1 inhibition | Phase I/II clinical trials | AACR/SABCS | Studies in metastatic settings | [80,81,82] |

| Curcumin | Rhizome of Curcuma longa | Breast | Inhibits NF κB, STAT3, PI3K/Akt; induces apoptosis | Phase II adjunct trials | NIH, NCI | Oral bioavailability/efficacy trials | [83,84,85,86] |

| EGCG (Polyphenon E) | Leaves of Camellia sinensis | Breast | Epigenetic, PI3K/Akt, anti angiogenic | Not yet approved; Still under investigation for Phase I/II clinical trials | NCI | NCT02580279 ongoing | [7,24,71] |

| Resveratrol | Skin of grapes (Vitis vinifera) | Breast | Activates p53; ROS-induced apoptosis | Not yet approved; Still under investigation for Phase I early-phase trials | NIH, NCI | Early breast cancer trials | [7,87,88,89,90] |

| Parthenolide | Leaves of Tanacetum parthenium | Triple Negative Breast Cancer | NF κB inhibition, ROS generation | Not yet approved; Still under investigation for Preclinical only | NIH, NCI | Microenvironment model exploration | [18,91,92] |

| Dihydroartemisinin (DHA) | Derived from Artemisia annua | Breast | Induces ROS-mediated apoptosis & ferroptosis | Not yet approved; Still under investigation for Preclinical only | NIH, NCI | Combination therapy preclinical | [93,94,95] |

| Natural Compounds | Source Plant/Origin | Type of Cancer | Conventional Therapy Used | Mechanism of Action | Stage of Cancer | Treatment Investigated | Ongoing Research | Study Limitations | Future Directions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curcumin | Curcuma longa (turmeric) | HR+, TNBC | Doxorubicin, Paclitaxel, Cisplatin | NF-κB and PI3K/Akt inhibition; ↑ROS; p53-mediated apoptosis; ABC transporter inhibition (MDR reversal) | All stages | In vitro, in vivo; early-phase clinical formulations | Yes | Poor solubility, low bioavailability | Nanoformulations, targeted delivery; controlled trials | [83,84,85,86] |

| Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) | Camellia sinensis (green tea) | HR+, TNBC | Doxorubicin, Paclitaxel, Radiotherapy | ↑Bax/↓Bcl-2/↑caspase-3; ↑ROS; impaired DNA repair/checkpoints (radiosensitization) | Early– advanced | In vitro, xenografts; limited clinical/epidemiologic | Yes | Low oral bioavailability; dose-dependent effects | Optimized delivery systems; dose-finding trials | [114,117] |

| Resveratrol | Grapes, berries, peanuts | HR+ | Tamoxifen; Radiotherapy | Modulates ER–PI3K/Akt/MAPK crosstalk; restores antiestrogen sensitivity; radiosensitization | Early–locally advanced | In vitro, murine models | Yes | Variable bioavailability; dose/timing sensitivity | Biomarker-guided endocrine combinations; formulation advances | [87,154,174] |

| Genistein | Soybeans, legumes | HR+ | Tamoxifen; Aromatase inhibitors | CDK inhibition; ↑p21; ER/growth factor pathway modulation; delays endocrine resistance | Early– advanced | In vitro, murine models; limited clinical nutrition signals | Yes | Phytoestrogenic antagonism risk | Patient stratification; dosing optimization trials | [163,164,165] |

| Quercetin | Onion, apple, fruits/vegetables | TNBC, MDR | Doxorubicin, Docetaxel | Inhibits ABC transporters; ↑drug accumulation; enhances caspase-dependent apoptosis | Advanced, resistant | In vitro; limited in vivo | Yes | Sparse clinical data; stability/PK | Resistance-focused preclinical→early clinical studies | [121,123,124,151] |

| Berberine | Berberis vulgaris | TNBC | Cisplatin | G0/G1 arrest; ↑DNA damage response; caspase-3 activation; pro-apoptotic signaling | All stages | In vitro, animals | Yes | Dose-related toxicity | Liposomal/targeted delivery; safety profiling | [160,161,162] |

| Caffeic acid | Coffee, fruits, vegetables | HR+, TNBC | Paclitaxel | ↑ROS; mitochondrial depolarization; G1/S arrest; anti-angiogenic activity | Early– advanced | In vitro, xenografts | Yes | Limited human data | Translational combination trials | [166,167] |

| Ferulic acid | Whole grains, rice bran | TNBC | Paclitaxel | Suppresses PI3K/Akt/NF-κB; ↓MMP-9; inhibits EMT, invasion, angiogenesis | Advanced/metastatic | In vitro, orthotopic models | Yes | Limited human data | Metastasis-focused translational studies | [175,176,177] |

| Silymarin | Milk thistle | Mixed subtypes (incl. TNBC) | Paclitaxel (chemosensitization) | NF-κB/MAPK modulation; anti-inflammatory; apoptosis | All stages | In vitro, animals | Yes | Limited human evidence; extract variability | Early-phase clinical trials; standardization | [178] |

| Thymoquinone | Nigella sativa | TNBC | Doxorubicin (chemosensitization) | ↑ROS; p38 MAPK activation; mitochondrial apoptosis | Advanced | In vitro, xenografts | Yes | Toxicity concerns at higher doses | Safer analogs; formulation advances | [134,179] |

| Ginsenoside Rg3 | Panax ginseng | HR+, TNBC | Cyclophosphamide; multi-drug regimens | Anti-proliferative; immune modulation; anti-angiogenic | All stages | Preclinical; selected clinical contexts regionally | Yes | Cost/supply; standardization | Synthetic production; co-delivery systems | [78,79,81] |

| Apigenin | Parsley, chamomile | HER2+driven signaling (preclinical) | HER2+pathway targeting contexts | Promotes apoptosis; inhibits STAT3/NF-κB; HER2/neu degradation | Advanced | In vitro | Yes | Poor solubility | Formulation improvements; mechanistic validation | [180,181] |

| Lycopene | Tomato | HR+ | Radiation therapy (adjunct nutrition) | Antioxidant; radioprotective; supports DNA damage response/redox balance | Early-stage | Preclinical; mixed clinical nutrition studies | Yes | Variable absorption; dietary confounders | Dietary guidance; adjunct clinical trials | [182,183] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mansouri, H.; Irchad, A.; Rubaka, C.; Kisula, L.; Hamza, A.A.; Sauli, E. Botanical Adjuvants in Oncology: A Review on Natural Compounds in Synergy with Conventional Therapies as Next-Generation Enhancers of Breast Cancer Treatment. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2026, 48, 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48020170

Mansouri H, Irchad A, Rubaka C, Kisula L, Hamza AA, Sauli E. Botanical Adjuvants in Oncology: A Review on Natural Compounds in Synergy with Conventional Therapies as Next-Generation Enhancers of Breast Cancer Treatment. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2026; 48(2):170. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48020170

Chicago/Turabian StyleMansouri, Hidaya, Ahmed Irchad, Clarence Rubaka, Lydia Kisula, Abdou Azali Hamza, and Elingarami Sauli. 2026. "Botanical Adjuvants in Oncology: A Review on Natural Compounds in Synergy with Conventional Therapies as Next-Generation Enhancers of Breast Cancer Treatment" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 48, no. 2: 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48020170

APA StyleMansouri, H., Irchad, A., Rubaka, C., Kisula, L., Hamza, A. A., & Sauli, E. (2026). Botanical Adjuvants in Oncology: A Review on Natural Compounds in Synergy with Conventional Therapies as Next-Generation Enhancers of Breast Cancer Treatment. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 48(2), 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48020170