1. Introduction

Since 1980, the incidence of liver cancer has tripled, and its death rate has doubled [

1,

2]. Factors such as alcohol consumption, metabolic dysfunction-associated liver disease (MASLD), hepatitis virus infections, and genetic disorders involving copper or iron overload contribute to liver cancer, one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths worldwide [

3,

4]. Although these etiologic factors differ, they converge on a common pathogenic mechanism: they induce chronic hepatic inflammation and fibrosis, which are major drivers of hepatocarcinogenesis [

5,

6,

7].

The prognosis of patients with liver cancer depends on the cancer stage. Approximately half of the individuals diagnosed with Stage I disease have a relatively favorable prognosis and live beyond four years (

https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/liver-cancer/survival;

https://www.hepb.org/research-and-programs/liver/staging-of-liver-cancer/survival-rates, both accessed on 30 December 2025). Patients diagnosed with Stage I liver cancer are treated with the standard of care (SOC) (liver resection, transplantation, or ablation) [

8,

9]. However, a small subset of patients with Stage I disease die within the first year [

10]. Developing a prognostic biomarker panel to identify high-risk Stage I patients could be clinically beneficial for identifying those who may benefit from innovative treatments, including newer therapies. Currently, no prognostic biomarker panel specifically focused on Stage I liver cancer is available.

The Long–Evans Cinnamon (LEC) rat model, which mimics Wilson’s Disease (WD), naturally accumulates copper in the liver due to a 900 bp deletion in the rat Atp7b gene, leading to liver injury and hepatitis, which are common initiating events in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [

11,

12,

13,

14]. The LEC model is important for understanding and treating fibrosis- and inflammation-mediated HCC.

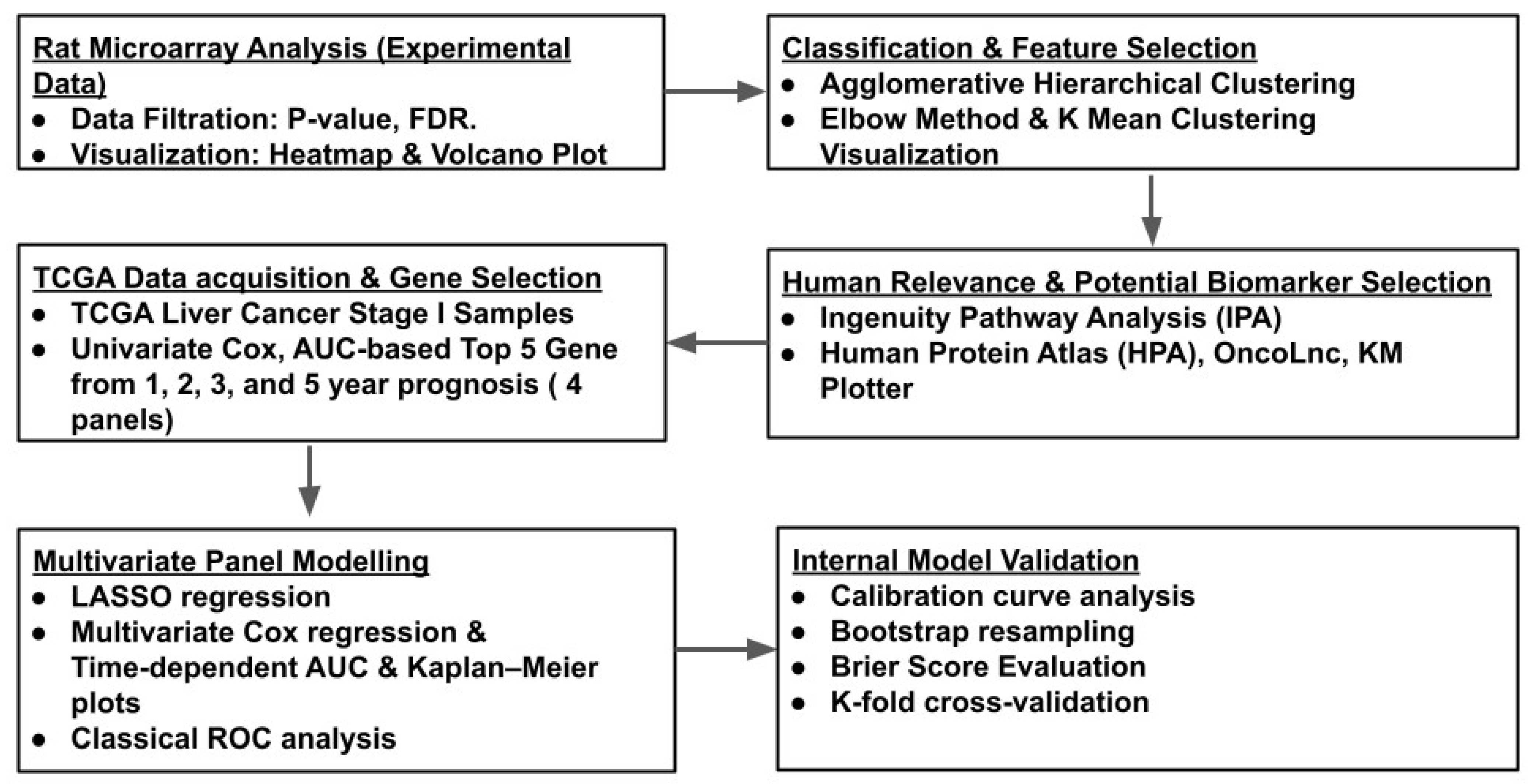

In this study, we hypothesized that differentially expressed genes between liver cancer and adjacent normal tissues may provide novel insights into cancer sustenance and progression, potentially revealing new prognostic signatures for the disease. We generated and analyzed a rat microarray gene expression profile by comparing liver tumors and adjacent normal tissues from the same LEC rats, covering approximately 30,000 genes. Using an array of machine learning pipelines and the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database for liver cancer, we translated the rat microarray results into a five-gene signature panel associated with the 1-year prognosis of Stage I liver cancer.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal and Liver Tissues

LEC rats were maintained under standard conditions following the IACUC-approved protocol (#07-065) [

15]. Liver tissues were collected from three LEC rats at 84 weeks, paraffin-embedded, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H and E). Adjacent normal (late chronic hepatitis, tumor-adjacent normal) and tumor tissue sections, both collected at 84 weeks, were identified after histopathological review by a pathologist who was board-certified in hematopathology, anatomic pathology, and clinical pathology, as described previously [

15].

2.2. Total RNA Extraction and Gene Expression Microarray

We performed a gene expression microarray analysis using total RNA to identify differences in gene expression between tumor and adjacent normal tissues. Total RNA was isolated from the 84-week adjacent normal and 84-week tumor LEC liver tissues using the RNAeasy (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA extracted from the tissues was hybridized to the Affymetrix GeneChip Rat Genome 230 2.0 Array (Affymetrix Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) and probed for 30,000 rat transcripts. Raw data were background-corrected, normalized, and RMA-summarized. Differential expression analysis between 84-week tumor and 84-week adjacent normal samples was performed using Biometric Research Branch (BRB)-ArrayTools, which applies a Random Variance Model (RVM). Fold changes between the 84-week tumor and 84-week adjacent normal tissues, as well as the associated

p-values, were calculated to identify statistically significant (

p-value ≤ 0.05) differentially expressed genes between the two groups. In addition, a fold change cutoff of ±2 and an FDR < 0.25 cutoff were used to select genes for analysis following GSEA guidelines [

16].

2.3. Visualization of Gene Expression Data with Volcano Plot

A volcano plot was generated to visualize the significant gene expression changes between 84-week tumors and 84-week adjacent normal tissues, with a cutoff of +/− 2-fold. The Python seaborn package (.sns) was used for the volcano plot to visualize changes between 84-week tumor and 84-week adjacent normal samples. Python 3.12.12 (Google colaboratory) was used for this and all other downstream analyses.

2.4. Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering

Hierarchical clustering was employed to identify potential additional clusters within the upregulated and downregulated groups between the 84-week tumor and 84-week adjacent normal tissues [

17] using the Python package schlearn (.sch).

2.5. K-Means Clustering and Elbow Method

We determined the optimal number of clusters using the “elbow” method within the upregulated and downregulated groups by comparing 84-week tumor and 84-week adjacent normal tissues. K-means clustering was then employed to cluster and graphically represent the data in a 3D scatter plot, rather than a dendrogram [

18].

2.6. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis for Each Cluster

Each cluster obtained from the K-means clustering analysis within the over- and under-expressed groups was subjected to pathway analysis using QIAGEN Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (QIAGEN IPA) to understand the interplay between biological pathways. In addition, results with −log(p) > 1.3, a z-score cutoff ≥ 2 for pathway activation, and a z-score cutoff ≤ −2 for pathway inhibition were considered significant.

2.7. Human Protein Atlas (HPA), OncoLnc, and Kaplan–Meier (KM) Plotter for Potential Prognostic Biomarkers

The top ten genes from the clusters obtained from K-means clustering analysis of the over- and under-expressed groups were investigated for their prognostic potential using three web-based tools—Human Protein Atlas (HPA), OncoLnc, and KM plotter-based log-rank test (Mantel–Cox Test), with p-value < 0.05 (HPA and KM plotter)—as well as hazard ratios and the available literature.

2.8. Analysis of TCGA Stage I Liver Cancer Patient Data

We extracted RNA-seq TPM expression data from HPA for the top candidate genes with potential prognostic value for Stage I liver cancer patients, along with associated clinical metadata, including survival time, survival status, tumor stage, age, and sex, from the TCGA liver cancer dataset.

2.9. One-Year Survival Prediction by Age and Sex for Stage I Liver Cancer

We fit Cox proportional hazards models to assess whether age and sex predict 1-year survival. First, we used lifelines’ CoxPHFitter on age and sex. In parallel, we trained a scikit-survival pipeline—StandardScaler for age and OneHotEncoder(drop = “if_binary”) for sex, feeding CoxPHSurvivalAnalysis—with a 70/30 train–test split stratified by the event indicator. Discrimination at 365 days was evaluated with time-dependent AUC (cumulative_dynamic_auc), and overall ranking with the IPCW C-index—inverse-probability-of-censoring-weighted concordance—which adjusts for right-censoring by reweighting pairs using the estimated censoring distribution.

2.10. Time-Dependent Prognostic Significance Analysis of Individual Genes for Stage I Liver Cancer

Univariate Cox proportional hazards modeling was performed separately for 1-, 2-, 3-, and 5-year time points for each gene using survival data (days and status) and gene expression levels. Patients were censored if they were alive before the defined time point but had no follow-up information beyond that point.

We first identified optimal thresholds to group patients into “High” and “Low” expression groups using the lifelines.statistics.logrank_test package. Gene expression quantile thresholds from the 20th to 80th percentile were tested and compared for their impact on survival distributions. The threshold yielding the smallest p-value (log-rank test) was selected as the optimal cutoff.

For each gene and time point, a univariate Cox proportional hazards model was fitted using the CoxPHFitter module in Python lifelines to estimate the hazard ratio (HR), 95% confidence interval (CI), p-value, and time-dependent area under the curve (AUC). Kaplan–Meier survival curves were generated (Kaplan–Meier Fitter).

2.11. Ranking Top Genes for Predicting 1-, 2-, 3-, and 5-Year Survival

To identify the top-performing prognostic genes at each time point (1, 2, 3, and 5 years), we ranked the genes with the highest AUC values derived from the univariate Cox models and then selected the top five. With the selected genes, we constructed four time-specific five-gene signature panels, referred to as Panel-A, Panel-B, Panel-C, and Panel-Ds, for downstream analysis.

2.12. Time-Dependent Multivariate LASSO Regression for Survival and Gene Selection

We applied LASSO regression (sklearn.linear_model.LassoCV) to standardized gene expression values (sklearn.preprocessing.StandardScaler) to construct a separate multivariate risk score for each of the four time-specific panels: Panel-A, Panel-B, Panel-C, and Panel-D.

2.13. Multivariate Cox Regression Survival Analysis (Time-Dependent AUC)

The four prognostic panels (Panel-A, Panel-B, Panel-C, and Panel-D) were used to train a separate multivariate survival model using the Cox proportional hazards model (CoxPHSurvival Analysis from scikit-survival), with the corresponding five genes included as covariates.

The performance of each model was evaluated using cumulative dynamic time-dependent AUC calculations (cumulative_dynamic_auc, scikit-survival) at one, two, three, and five years. This method accounts for right-censored data and compares risk score predictions with survival status at specified future time points. AUC values with 95% and 80% CIs were calculated for each model across all evaluation years and visualized using matplotlib.pyplot to compare the cross-time point prognostic performance.

2.14. Classical Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Analysis

ROC analysis was performed using the roc_curve and auc functions from the sklearn.metrics module. Cox proportional hazards models (CoxPHSurvivalAnalysis, scikit-survival) were trained with each of the four prognostic panels (Panel-A, Panel-B, Panel-C, and Panel-D) at each evaluation year (1, 2, 3, and 5 years). The models’ predicted risk scores were evaluated against the derived binary outcome labels.

Patients were labeled as positive if they died in or before the specified evaluation year and negative if they were alive beyond that point; they were censored if they were alive before the time point but lacked follow-up information beyond that point. ROC curves were constructed, and the AUC was calculated to assess the discriminative ability of the risk scores at each evaluation time point.

2.15. Generation of Kaplan–Meier Survival Curves by Comparing Optimized Risk Groups Across Four Panels

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were fitted using the four prognostic gene panels to predict survival at 1, 2, 3, and 5 years (CoxPHSurvival Analysis, sksurv.linear_model). For each panel, patients were stratified into “High” and “Low” risk groups based on an optimal cutoff determined by minimizing the log-rank p-value across the 20th to 80th percentile of the predicted risk score distribution (logrank_test, lifelines.statistics).

For each risk stratification, we further calculated the classification performance metrics by identifying thresholds that achieved 95% and 99% specificity in predicting events at each time point. The corresponding sensitivity values were computed using the confusionmatrix function from sklearn.metrics.

2.16. Calibration Curves for Multivariable Cox Survival Models Constructed Using the Four Prognostic Panels at 1-, 2-, 3-, and 5-Year Time Points

To assess the calibration of our multivariable Cox survival models, we predicted individual survival probabilities at future time points (1, 2, 3, and 5 years) using model-derived survival functions (predict_survival_function, sksurv.linear_model). Each model corresponds to one of the four prognostic panels developed previously.

The patients were grouped into five bins based on the quantiles of the predicted survival probability. For each bin, we computed the average predicted survival and compared it with the observed survival fraction to generate the calibration curves. Observed survival was defined as 1 for patients who were alive beyond the evaluation time point and 0 for those who experienced an event (death) at or before that time. Patients censored before the evaluation time point were excluded from the analysis to ensure accuracy of the results. The calibration curve function from sklearn.calibration was used to compute the observed versus predicted survival values for each bin.

2.17. Harrell’s Concordance Index (C-Index) for Cox Model Predictions Across Four Prognostic Panels

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were trained using the four prognostic panels (Panel-A, Panel-B, Panel-C, and Panel-D). Model performance was evaluated at 1, 2, 3, and 5 years by computing the concordance index (C-index) using the concordance_index_censored function in the sksurv.metrics module.

2.18. Bootstrapping for Risk Group Hazard Ratios

To estimate the robustness of hazard ratios (HRs) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the four prognostic panels at each evaluation year (1, 2, 3, and 5 years), we performed 100 bootstrap resamples using resamples from sklearn.utils. For each resample, a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model was fitted to calculate risk scores based on the five genes in the corresponding panel.

Simulated patients were grouped into “High” and “Low” risk groups using an optimal risk score threshold identified from the minimum log-rank p-value measured across quantiles from the 20th to 80th percentile (logrank_test, lifelines.statistics). A univariate Cox model with the binary risk group as a covariate was then fitted using CoxPHFitter (lifelines) to estimate the hazard ratio (HR).

The 95% confidence intervals for the hazard ratios (HRs) were computed using log-transformed HR distributions of the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles across bootstrap iterations.

2.19. Hazard Ratios (HRs) and Concordance Indices (C-Indices) from 5-Fold Cross-Validation

A multivariable Cox proportional hazards model (CoxPHSurvivalAnalysis, scikit-survival) was trained using 5-fold cross-validation for each of the four prognostic gene panels for each evaluation year (1, 2, 3, or 5 years).

Within each training fold, an optimal risk score cutoff was identified by minimizing the log-rank p-value, as described previously. This threshold was then applied to both the training and test sets to assign patients to “High”- or “Low”-risk groups. Hazard ratios (HRs) were estimated from the test set using univariate Cox models (CoxPHFitter, lifelines) with the binary risk group as the sole covariate.

To evaluate discriminative performance, the concordance index (C-index) was computed on the test set using continuous risk scores (concordance_index_censored, sksurv.metrics). The mean HRs, confidence intervals, and C-index statistics were aggregated across valid folds to assess the prognostic accuracy and robustness of each panel at different time points.

2.20. Brier Score Evaluation for Survival Predictions

Brier scores were computed to assess the accuracy and calibration of the survival probability estimates from each gene panel when compared to actual outcomes at 1, 2, 3, and 5 years [

19]. For each panel, the top five genes were binarized using their respective optimal cutoff values, and a Cox proportional hazards model was trained using CoxPHSurvival Analysis from scikit-survival.

Predicted survival probabilities were obtained from the model’s estimated survival functions (predict_survival_function) and interpolated at each evaluation time point using the Brier score function from sksurv. Metrics were used to compute time-dependent Brier scores, which quantify the mean squared difference between the predicted survival probability and actual outcome (alive vs. event) at a given time.

4. Discussion

Since 1980, the liver cancer death rate has more than doubled. While patients diagnosed at Stage I generally have a relatively favorable prognosis, the outcomes vary widely. About half of Stage I patients live for more than 4 years after they are diagnosed, but a small but significant number of patients die within the first year [

8,

9] (

https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/liver-cancer/survival;

https://www.hepb.org/research-and-programs/liver/staging-of-liver-cancer/survival-rates, both accessed on 30 December 2025). Currently, no clinical tests are available to identify which Stage I patients are at a higher risk of early death. Such a panel could potentially inform risk-adapted treatment intensification (e.g., consideration of adjuvant systemic therapy) in a narrowly defined high-risk subgroup.

To address this unmet need, we developed a new multi-gene panel associated with 1-year survival in patients with Stage I liver cancer. We restricted the cohort to Stage I to limit treatment heterogeneity; at this stage, management typically follows the standard of care (SOC), and covariates such as prior treatment are limited. Our results also showed that age and sex have no discriminating potential. This focus reduced potential confounding from variations in therapy, sex, and age in our downstream analyses. It is important to note that while prognostic genes can be identified directly from human data, starting with an animal model and then confirming the results in patients strengthens the findings by integrating two independent systems. Panel-D demonstrated reliable performance throughout internal validation and was particularly associated with 1-year survival in Stage I patients. The Panel-D genes were

ANXA2,

FXYD3,

ITGB4,

PAQR9, and

USP54. Panel-A showed reliable performance in most of the internal validation, but failed to meet cross-validation criteria in the current cohort. Evaluation in a larger dataset with greater event accrual may be informative to assess whether performance is affected by limited sample size. The novelty of this work lies in integrating five seemingly weakly correlated genes into a newly constructed biomarker panel. Our approach is mechanism-agnostic, consistent with emerging approaches in molecular diagnostics, where empirical discovery precedes full biological interpretation. For example, the Grail assay uses approximately 100,000 informative differentially methylated regions for multi-cancer early detection (MCED) [

35].

This proof-of-concept study underwent rigorous internal validation following the REporting recommendations for tumor MARKer (REMARK) guidelines for prognostic studies [

36] and recent guidelines with low event numbers [

37]. REMARK guidelines acknowledge that an external validation set “often will not be available” and that “internal” validation procedures such as “cross-validation” and “bootstrapping” are useful for understanding the reliability of the modeling. A split-test approach is unreliable for small event sizes [

37,

38] and was therefore avoided.

Although external validation is ideal, Stage I liver cancer samples with sufficient events after censoring at the 1-year time point were difficult to obtain. Moreover, RNA-Seq results are affected by various factors, including laboratory conditions, instruments, extraction procedures, sequencing depth, and sample handling [

39,

40]. Therefore, a publicly available external database may not be appropriate for validating this study. Since we reported results across all five folds (

Table S4), each sample was tested exactly once in a distinct validation set, ensuring comprehensive evaluation across the dataset and following the gold-standard REMARK guideline. In clinical settings, an assay is typically developed, locked, and analytically characterized/validated prior to clinical validation. The test and training sets were evaluated using the same locked assay in clinical protocols and in good clinical practice (

https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf20/P200010S008B.pdf;

https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf23/P230043B.pdf, both accessed on 30 December 2025). Our panel included only five genes and could be readily adapted to a low-cost qPCR- or ddPCR-based test. Once the test has been adapted and analytically characterized, we plan to validate it using controlled Stage I patient samples with a sufficient number of events.

One potential limitation of this investigation is the lack of a separate rat model control. To address this limitation, a skilled pathologist examined the sample to ensure accurate identification of both tumor and non-tumor regions. In addition, this study used only three rats for gene expression analysis. To address this concern, we showed that gene expression patterns were consistent across all three animals (

Figure 3B). IPA showed the activation of six pathways known to be activated in HCC, validating the biological relevance of our findings. In addition, as a safeguard, the genes with expression changes in the microarray experiment were not used directly in the machine learning models but rather evaluated for their prognostic value using public datasets to limit the likelihood of false discoveries. Similarly, another potential limitation is the use of an FDR threshold of 25%; however, this cutoff is consistent with GSEA guidelines for exploratory analyses, and candidate genes were subsequently validated using TCGA data, reducing the risk of false discovery [

16].

Another potential limitation of this study is the relatively small number of events (10%). To address this in bootstrapping, we implemented conservative safeguards during bootstrap resampling. In addition, we applied five-fold cross-validation to evaluate model discrimination and generalization and assessed model calibration using Brier scores and calibration plots. Together, these strategies ensured that hazard ratio estimates and association accuracy metrics provided a reliable evaluation of model performance. We also reported 95% and 80% confidence intervals of the AUC estimates for the multi-gene panels. Some confidence intervals at the early time point with fewer observed events do include 0.5, reflecting statistical uncertainty. We recognize that the modest number of events highlights the importance of future full-scale, multi-year sample collection and validation.