Exploring the Shared Diagnostic Biomarkers and Molecular Mechanisms Related to Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Rheumatoid Arthritis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

2.2. Differential Genes Expression Analysis

2.3. WGCNA and Identification of CGs

2.4. Enrichment Analysis of CGs

2.5. Screening of Potential Diagnostic Biomarkers in CGs

2.6. Validation of Diagnostic Models Based on Identified Hub Genes

2.7. Construction of PPI Network and Regulatory Network

2.8. ROC Curve Analysis of Hub Genes

2.9. Analysis of Immune Cell Infiltration

2.10. Cell Culture and Construction of Inflammation Model

2.11. Real-Time Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

2.12. Statistical Analysis

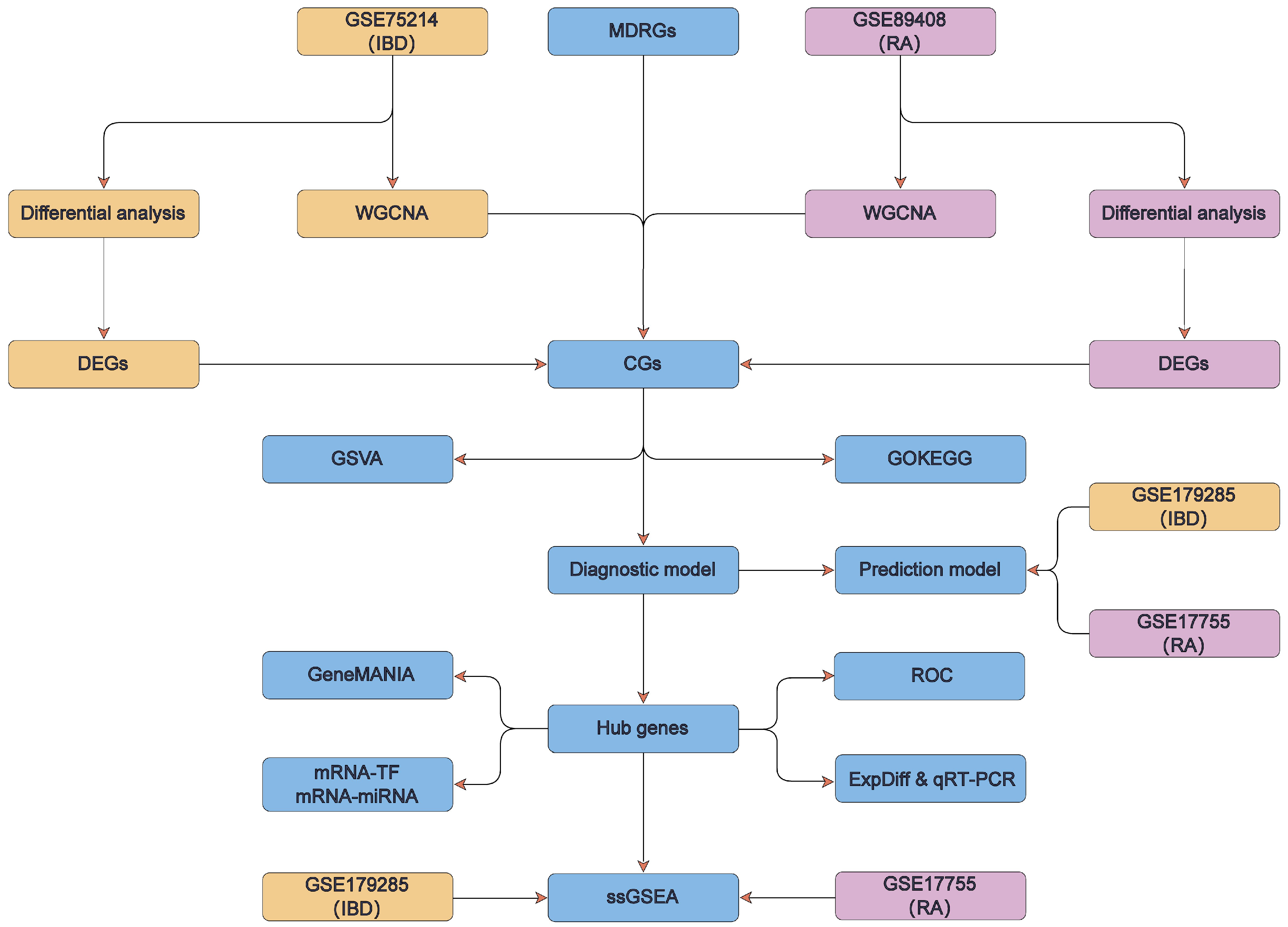

2.13. Technology Roadmap

3. Results

3.1. DEGs in IBD/RA Related to Mitochondrial Dysfunction

3.2. WGCNA and the Acquisition of CGs of IBD and RA

3.3. GO and KEGG Enrichment Analysis for CGs

3.4. GSVA for IBD and RA

3.5. Construction of Diagnostic Model for IBD and RA

3.6. Identification of Hub Genes and Network Analyses Based on Hub Genes

3.7. Validation of Diagnostic Models for IBD and RA

3.8. ROC Analysis and Validation of Hub Genes

3.9. Differential Expression Analysis and Validation of DUSP6 and PDIA4

3.10. Immune Infiltration Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, D.; Saikam, V.; Skrada, K.A.; Merlin, D.; Iyer, S.S. Inflammatory bowel disease biomarkers. Med. Res. Rev. 2022, 42, 1856–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogler, G.; Singh, A.; Kavanaugh, A.; Rubin, D.T. Extraintestinal Manifestations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Current Concepts, Treatment, and Implications for Disease Management. Gastroenterology 2021, 161, 1118–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotze, P.G.; Steinwurz, F.; Francisconi, C.; Zaltman, C.; Pinheiro, M.; Salese, L.; Ponce de Leon, D. Review of the epidemiology and burden of ulcerative colitis in Latin America. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2020, 13, 1756284820931739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Du, K.; Liang, C.; Wang, S.; Owusu Boadi, E.; Li, J.; Pang, X.; He, J.; Chang, Y.X. Traditional herbal medicine: Therapeutic potential in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 279, 114368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaravaglio, M.; Carbone, M.; Invernizzi, P. Autoimmune liver diseases. Minerva Gastroenterol. 2023, 69, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, K.; Dudek, P.; Stasiek, M.; Suchta, K. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes associated with autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Reumatologia 2023, 61, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisinger, C.; Freuer, D. Rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease: A bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2022, 55, 151992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Luo, Q.; Wu, Y.; Chen, G. Inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis share a common genetic structure. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1359857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman Wadan, A.H.; Abdelsattar Ahmed, M.; Hussein Ahmed, A.; El-Sayed Ellakwa, D.; Hamed Elmoghazy, N.; Gawish, A. The Interplay of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Oral Diseases: Recent Updates in Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Implications. Mitochondrion 2024, 78, 101942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Quintero, M.J.; Rodríguez-Díaz, C.; Rodríguez-González, F.J.; Fernández-Castañer, A.; García-Fuentes, E.; López-Gómez, C. Role of Mitochondria in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, E.A.; Mollen, K.P. Mitochondrial dysfunction in inflammatory bowel disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 3, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, P.S.; Kapur, N.; Barrett, T.A.; Theiss, A.L. Mitochondrial function and gastrointestinal diseases. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 21, 537–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Wang, J.; Hong, F.; Yang, S. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Promila, L.; Joshi, A.; Khan, S.; Aggarwal, A.; Lahiri, A. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis: Looking closely at fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Mitochondrion 2023, 73, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masoumi, M.; Alesaeidi, S.; Khorramdelazad, H.; Behzadi, M.; Baharlou, R.; Alizadeh-Fanalou, S.; Karami, J. Role of T Cells in the Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis: Focus on Immunometabolism Dysfunctions. Inflammation 2023, 46, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelzer, G.; Rosen, N.; Plaschkes, I.; Zimmerman, S.; Twik, M.; Fishilevich, S.; Stein, T.I.; Nudel, R.; Lieder, I.; Mazor, Y.; et al. The GeneCards Suite: From Gene Data Mining to Disease Genome Sequence Analyses. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2016, 54, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; He, Z.; Tang, T.; Wang, F.; Chen, H.; Li, B.; Chen, G.; Wang, J.; Tian, W.; Chen, D.; et al. Integrative Bioinformatics Analysis Revealed Mitochondrial Dysfunction-Related Genes Underlying Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 1372483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, L.; Ye, H.; Tu, W. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis in biomedicine research. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao 2017, 33, 1791–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, H.; Muruganujan, A.; Ebert, D.; Huang, X.; Thomas, P.D. PANTHER version 14: More genomes, a new PANTHER GO-slim and improvements in enrichment analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D419–D426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.Y. clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberzon, A.; Subramanian, A.; Pinchback, R.; Thorvaldsdóttir, H.; Tamayo, P.; Mesirov, J.P. Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 1739–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanzelmann, S.; Castelo, R.; Guinney, J. GSVA: Gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, H.; Valim, C.; Vegas, E.; Oller, J.M.; Reverter, F. SVM-RFE: Selection and visualization of the most relevant features through non-linear kernels. BMC Bioinform. 2018, 19, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engebretsen, S.; Bohlin, J. Statistical predictions with glmnet. Clin. Epigenet. 2019, 11, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, L.; Hu, M.; Chen, L.; Xu, B.; Song, Q. A nomogram for predicting overall survival in patients with low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma: A population-based analysis. Cancer Commun. 2020, 40, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Calster, B.; Wynants, L.; Verbeek, J.F.M.; Verbakel, J.Y.; Christodoulou, E.; Vickers, A.J.; Roobol, M.J.; Steyerberg, E.W. Reporting and Interpreting Decision Curve Analysis: A Guide for Investigators. Eur. Urol. 2018, 74, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, X.; Turck, N.; Hainard, A.; Tiberti, N.; Lisacek, F.; Sanchez, J.C.; Müller, M. pROC: An open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, M.; Rodriguez, H.; Lopes, C.; Zuberi, K.; Montojo, J.; Bader, G.D.; Morris, Q. GeneMANIA update 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W60–W64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.R.; Liu, S.; Sun, W.J.; Zheng, L.L.; Zhou, H.; Yang, J.H.; Qu, L.H. ChIPBase v2.0: Decoding transcriptional regulatory networks of non-coding RNAs and protein-coding genes from ChIP-seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D43–D50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.H.; Liu, S.; Zhou, H.; Qu, L.H.; Yang, J.H. starBase v2.0: Decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and protein-RNA interaction networks from large-scale CLIP-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D92–D97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, B.; Liu, L.; Li, A.; Xiang, C.; Wang, P.; Li, H.; Xiao, T. Identification and Verification of Immune-Related Gene Prognostic Signature Based on ssGSEA for Osteosarcoma. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 607622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, D.; Nie, X.; Yao, Y. Ge-Gen-Qin-Lian decoction alleviates the symptoms of type 2 diabetes mellitus with inflammatory bowel disease via regulating the AGE-RAGE pathway. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2024, 24, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Tao, M.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, X.; Wang, M. 4′-Methoxyresveratrol Alleviated AGE-Induced Inflammation via RAGE-Mediated NF-κB and NLRP3 Inflammasome Pathway. Molecules 2018, 23, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, P.; Theiss, A.; Han, J.; Feagins, L.A. Increased Cell Adhesion Molecules, PECAM-1, ICAM-3, or VCAM-1, Predict Increased Risk for Flare in Patients With Quiescent Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2017, 51, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellomo, C.; Furone, F.; Rotondo, R.; Ciscognetti, I.; Carpinelli, M.; Nicoletti, M.; D’Aniello, G.; Sepe, L.; Barone, M.V.; Nanayakkara, M. Role of Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases in Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Celiac Disease and Diabetes: Focus on the Intestinal Mucosa. Cells 2024, 13, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Tang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, D.; Ma, G. DUSP6 Inhibitor (E/Z)-BCI Hydrochloride Attenuates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammatory Responses in Murine Macrophage Cells via Activating the Nrf2 Signaling Axis and Inhibiting the NF-κB Pathway. Inflammation 2019, 42, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Gan, C.; Liu, H.; Hou, Y.; Su, X.; Xue, T.; Wang, D.; Li, P.; Yue, L.; Qiu, Q.; et al. Polyphyllin VI Ameliorates Pulmonary Fibrosis by Suppressing the MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathways via Upregulating DUSP6. Phytother. Res. 2024, 38, 5930–5948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Peng, Z.; Zhou, L.; Peng, R.; Li, X.; Zuo, W.; Gou, J.; Zhou, F.; Yu, S.; Huang, M.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acid Decreases the Expression of CEBPB to Inhibit miR-145-Mediated DUSP6 and Thus Further Suppresses Intestinal Inflammation. Inflammation 2022, 45, 372–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudry, K.; Langlois, M.J.; Montagne, A.; Cagnol, S.; Carrier, J.C.; Rivard, N. Dual-specificity phosphatase 6 deletion protects the colonic epithelium against inflammation and promotes both proliferation and tumorigenesis. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 6731–6745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, C.Y.; Hung, Y.J.; Shieh, Y.S.; Hsieh, C.H.; Lu, C.H.; Lin, F.H.; Su, S.C.; Lee, C.H. A novel potential biomarker for metabolic syndrome in Chinese adults: Circulating protein disulfide isomerase family A, member 4. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Seny, D.; Bianchi, E.; Baiwir, D.; Cobraiville, G.; Collin, C.; Deliège, M.; Kaiser, M.J.; Mazzucchelli, G.; Hauzeur, J.P.; Delvenne, P.; et al. Proteins involved in the endoplasmic reticulum stress are modulated in synovitis of osteoarthritis, chronic pyrophosphate arthropathy and rheumatoid arthritis, and correlate with the histological inflammatory score. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negroni, A.; Prete, E.; Vitali, R.; Cesi, V.; Aloi, M.; Civitelli, F.; Cucchiara, S.; Stronati, L. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and unfolded protein response are involved in paediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Dig. Liver Dis. 2014, 46, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, S.; De Vos, M.; Olievier, K.; Peeters, H.; Elewaut, D.; Lambrecht, B.; Pouliot, P.; Laukens, D. Involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress in inflammatory bowel disease: A different implication for colonic and ileal disease? PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althagafy, H.S.; Ali, F.E.M.; Hassanein, E.H.M.; Mohammedsaleh, Z.M.; Kotb El-Sayed, M.I.; Atwa, A.M.; Sayed, A.M.; Soubh, A.A. Canagliflozin ameliorates ulcerative colitis via regulation of TLR4/MAPK/NF-κB and Nrf2/PPAR-γ/SIRT1 signaling pathways. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 960, 176166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.J.; Lu, L.J.; Wang, J.J.; Ma, S.Y.; Xu, B.L.; Lin, R.; Chen, Q.S.; Ma, Z.G.; Mo, Y.L.; Wang, D.T. Tubson-2 decoction ameliorates rheumatoid arthritis complicated with osteoporosis in CIA rats involving isochlorogenic acid A regulating IL-17/MAPK pathway. Phytomedicine 2023, 116, 154875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, X.; Cao, X.; Jiang, M. E3 Ubiquitin Ligase RNF13 Suppresses TLR Lysosomal Degradation by Promoting LAMP-1 Proteasomal Degradation. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2309560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhu, Z.; Ma, Y.; Tang, T.; Wu, J.; Huang, F.; Xu, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, J. Rhizoma Alismatis Decoction improved mitochondrial dysfunction to alleviate SASP by enhancing autophagy flux and apoptosis in hyperlipidemia acute pancreatitis. Phytomedicine 2024, 129, 155629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, M.J.; O’Grady, S.; Tang, M.; Crown, J. MYC as a target for cancer treatment. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2021, 94, 102154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudersbach, T.; Siuda, D.; Kohlstedt, K.; Fleming, I. Epigenetic control of the angiotensin-converting enzyme in endothelial cells during inflammation. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golpich, M.; Amini, E.; Mohamed, Z.; Azman Ali, R.; Mohamed Ibrahim, N.; Ahmadiani, A. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Biogenesis in Neurodegenerative diseases: Pathogenesis and Treatment. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2017, 23, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Kim, D. Computational characterization of chromatin domain boundary-associated genomic elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 10403–10414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, L.; Xian, S.; Yang, D.; Yuan, M.; Dai, F.; Zhao, X.; et al. Prognostic value of infiltrating immune cells in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). J. Cell. Biochem. 2020, 121, 2571–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Platform | Species | Source | Disease | Control | Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSE75214 | GPL6244 | Homo sapiens | colon | 74 (IBD) | 11 | Experiment |

| GSE179285 | GPL6480 | Homo sapiens | colon | 23 (IBD) | 23 | Validation |

| GSE89408 | GPL11154 | Homo sapiens | synovial | 152 (RA) | 28 | Experiment |

| GSE17755 | GPL1291 | Homo sapiens | Peripheral blood | 112 (RA) | 53 | Validation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cui, L.; Ye, S.; Gu, Z.; Zhang, G.; Chen, T.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, C. Exploring the Shared Diagnostic Biomarkers and Molecular Mechanisms Related to Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Rheumatoid Arthritis. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2026, 48, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010089

Cui L, Ye S, Gu Z, Zhang G, Chen T, Zhou Y, Yu C. Exploring the Shared Diagnostic Biomarkers and Molecular Mechanisms Related to Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Rheumatoid Arthritis. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2026; 48(1):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010089

Chicago/Turabian StyleCui, Lijiao, Shicai Ye, Zhiwei Gu, Guixia Zhang, Tingen Chen, Yu Zhou, and Caiyuan Yu. 2026. "Exploring the Shared Diagnostic Biomarkers and Molecular Mechanisms Related to Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Rheumatoid Arthritis" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 48, no. 1: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010089

APA StyleCui, L., Ye, S., Gu, Z., Zhang, G., Chen, T., Zhou, Y., & Yu, C. (2026). Exploring the Shared Diagnostic Biomarkers and Molecular Mechanisms Related to Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Rheumatoid Arthritis. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 48(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010089