Collagen Type II-Targeting Lentiviral Gene Therapy for Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mouse Maintenance

2.2. Construction of LVs

2.3. Administration of LVs and Tissue Collection

2.4. Tissue Homogenization and GALNS Enzyme Assay

2.5. Evaluation of GAGs

2.6. Biodistribution of LVs

2.7. GALNS mRNA Expression Analysis

2.8. Systemic Toxicity Analysis

2.9. Detection of Anti-GALNS Antibodies

2.10. Luminex Assay

2.11. Pathology and Immunohistochemistry

2.12. Bone Morphometric Analysis

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Pathology of Newborn MPS IVA Mouse Bone

3.2. GALNS Enzyme Activities in Plasma and Tissues

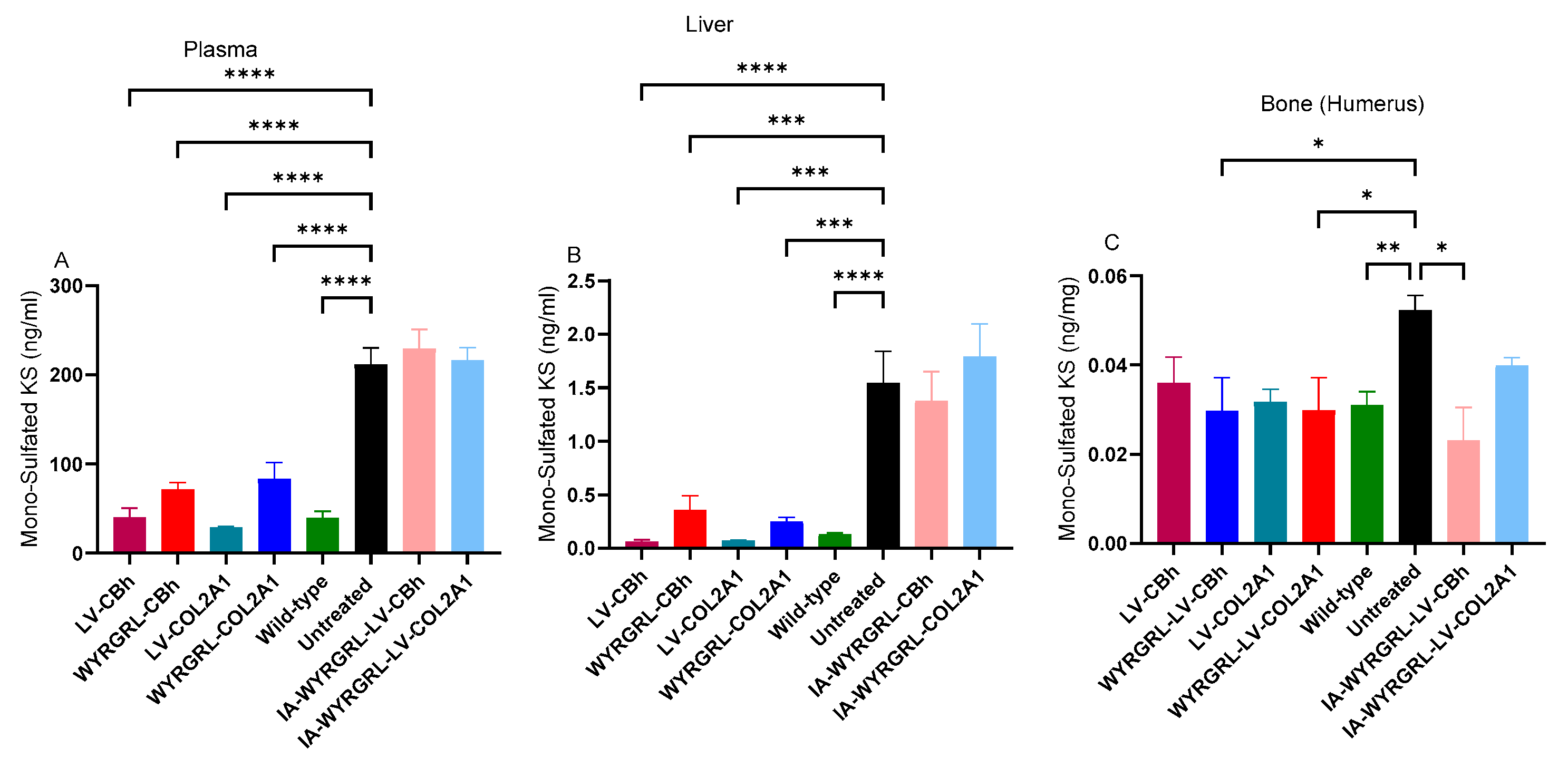

3.3. Mono-Sulfated KS Levels in Plasma and Tissues

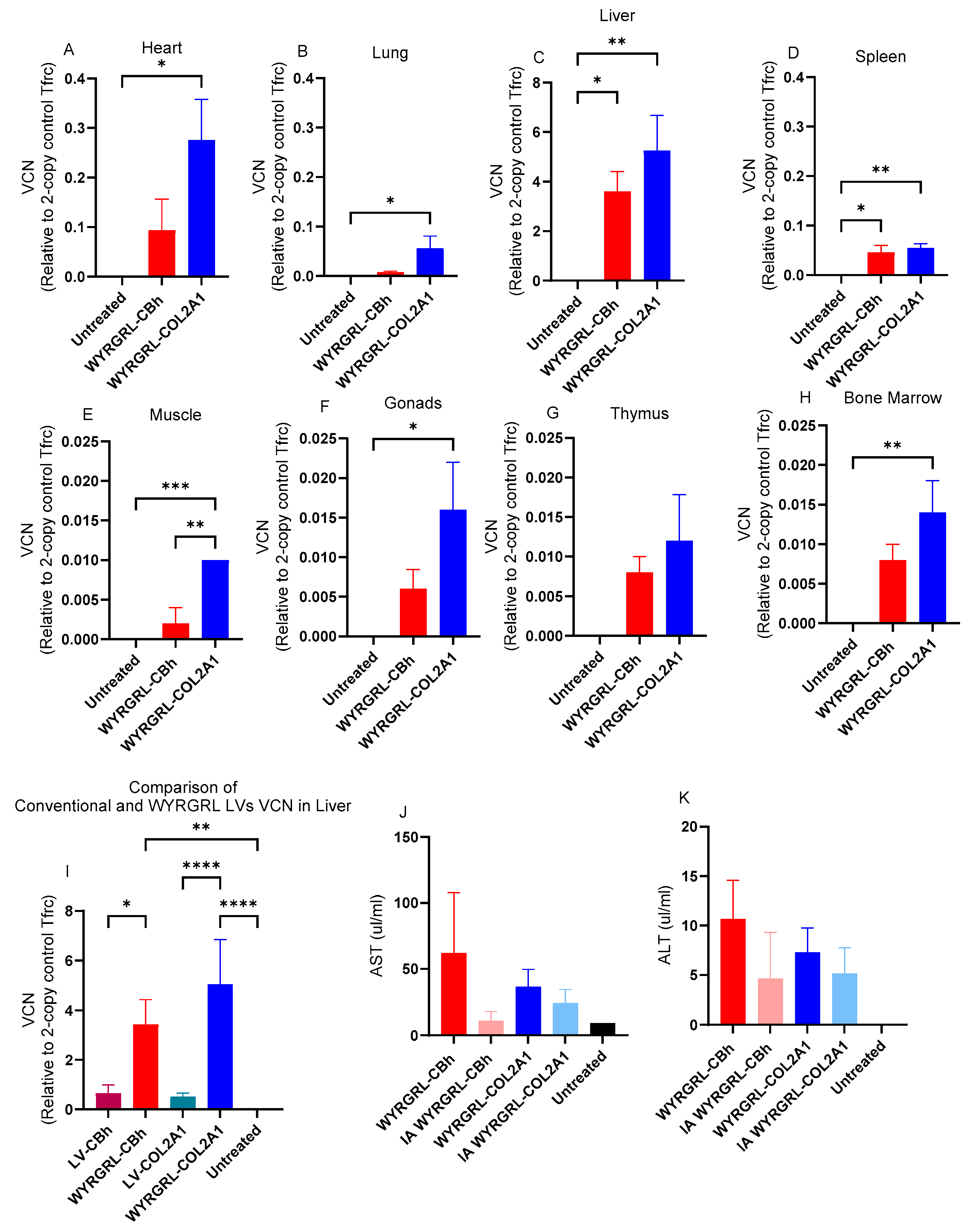

3.4. Distribution Patterns of LVs

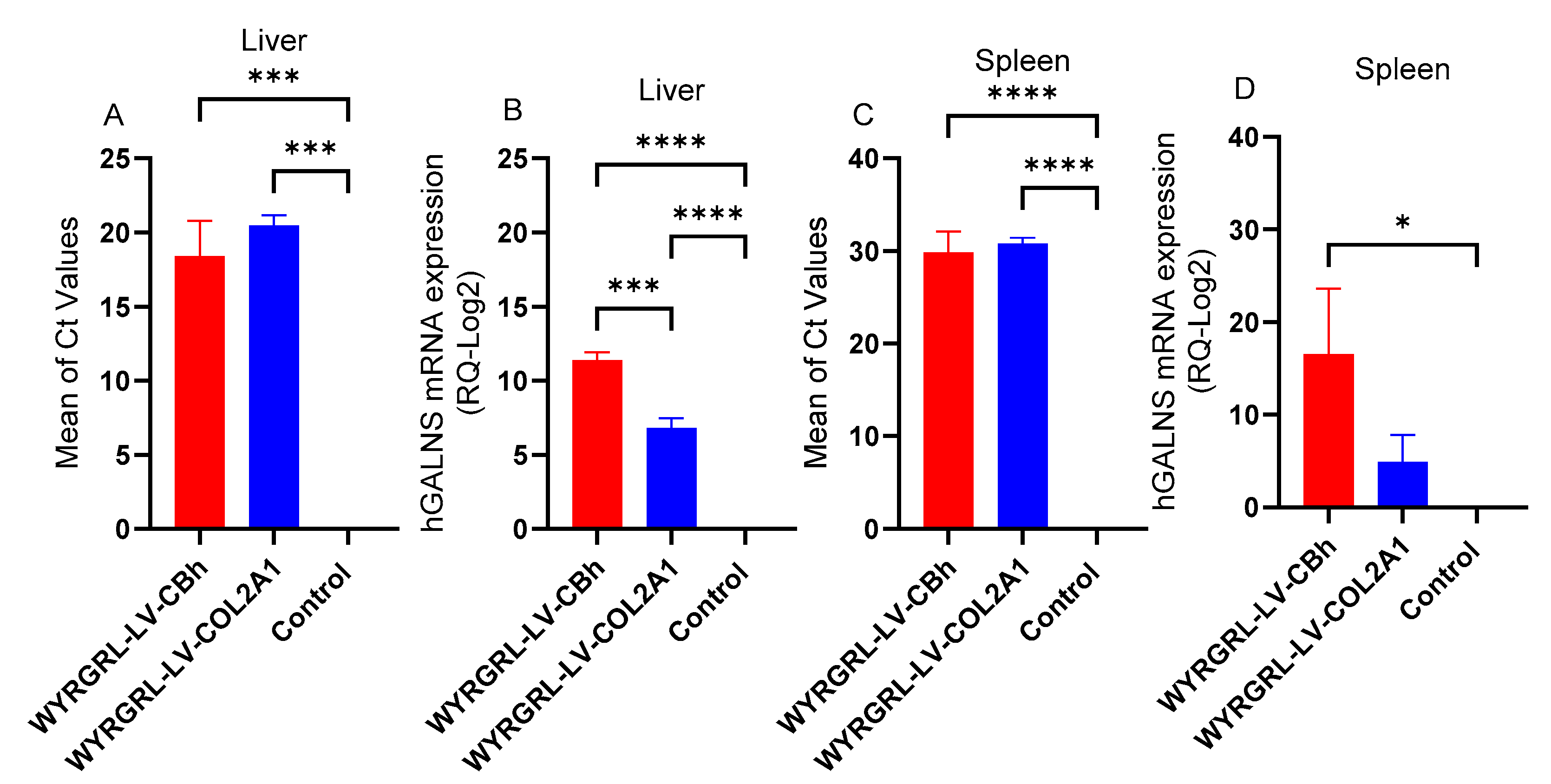

3.5. GALNS mRNA Expression After WYRGRGL-LVGT

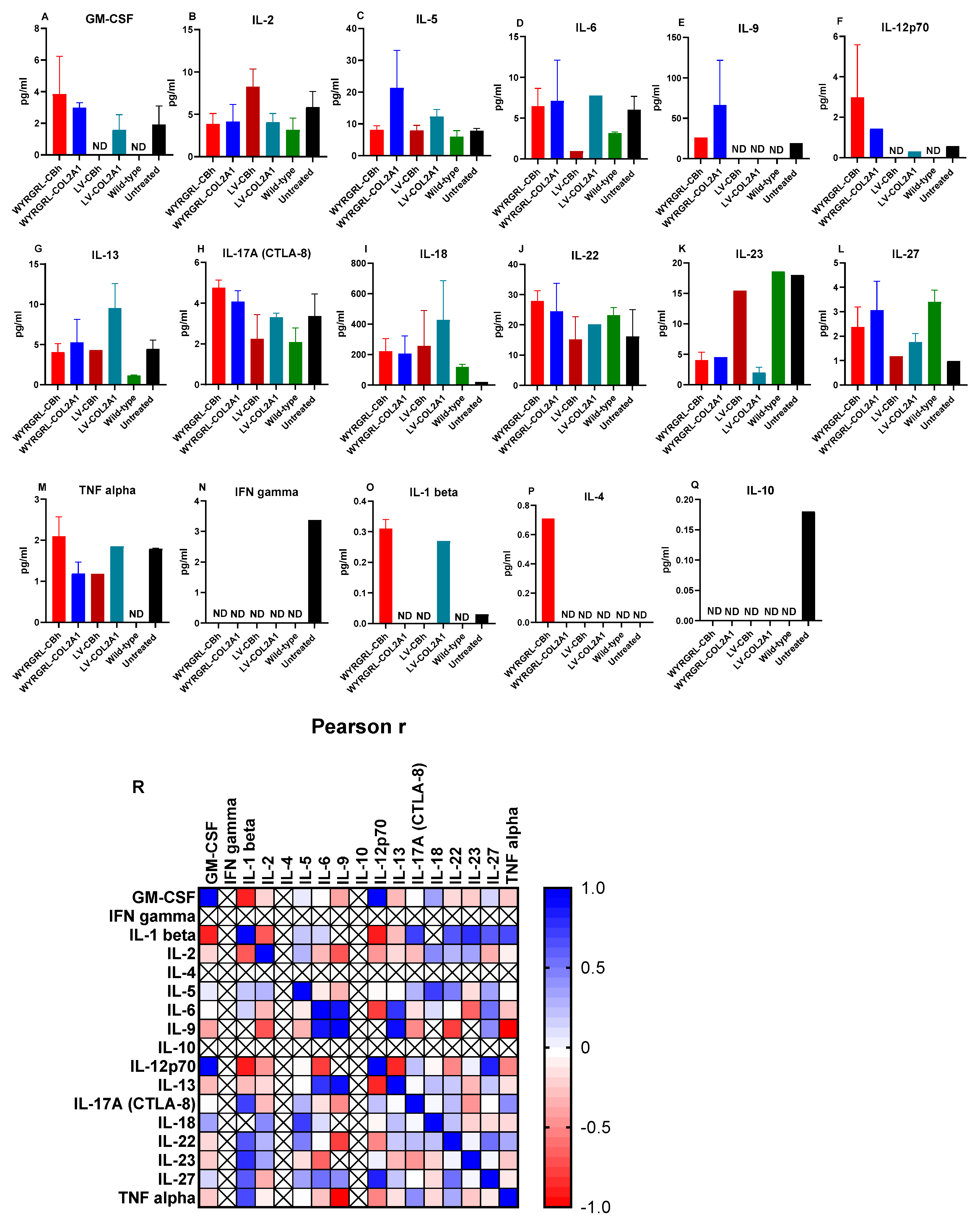

3.6. Cytokine Analysis

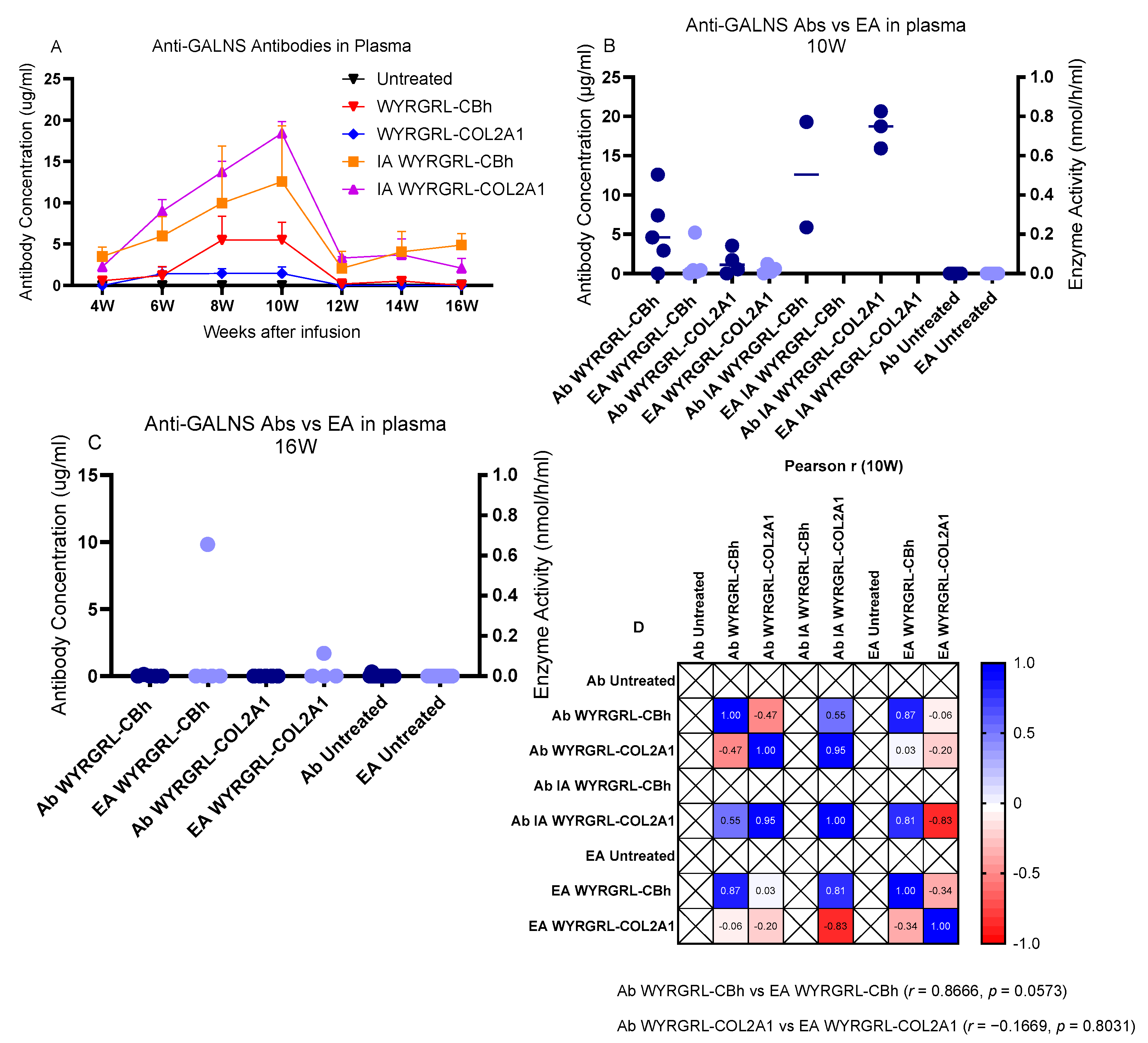

3.7. Anti-GALNS Antibodies

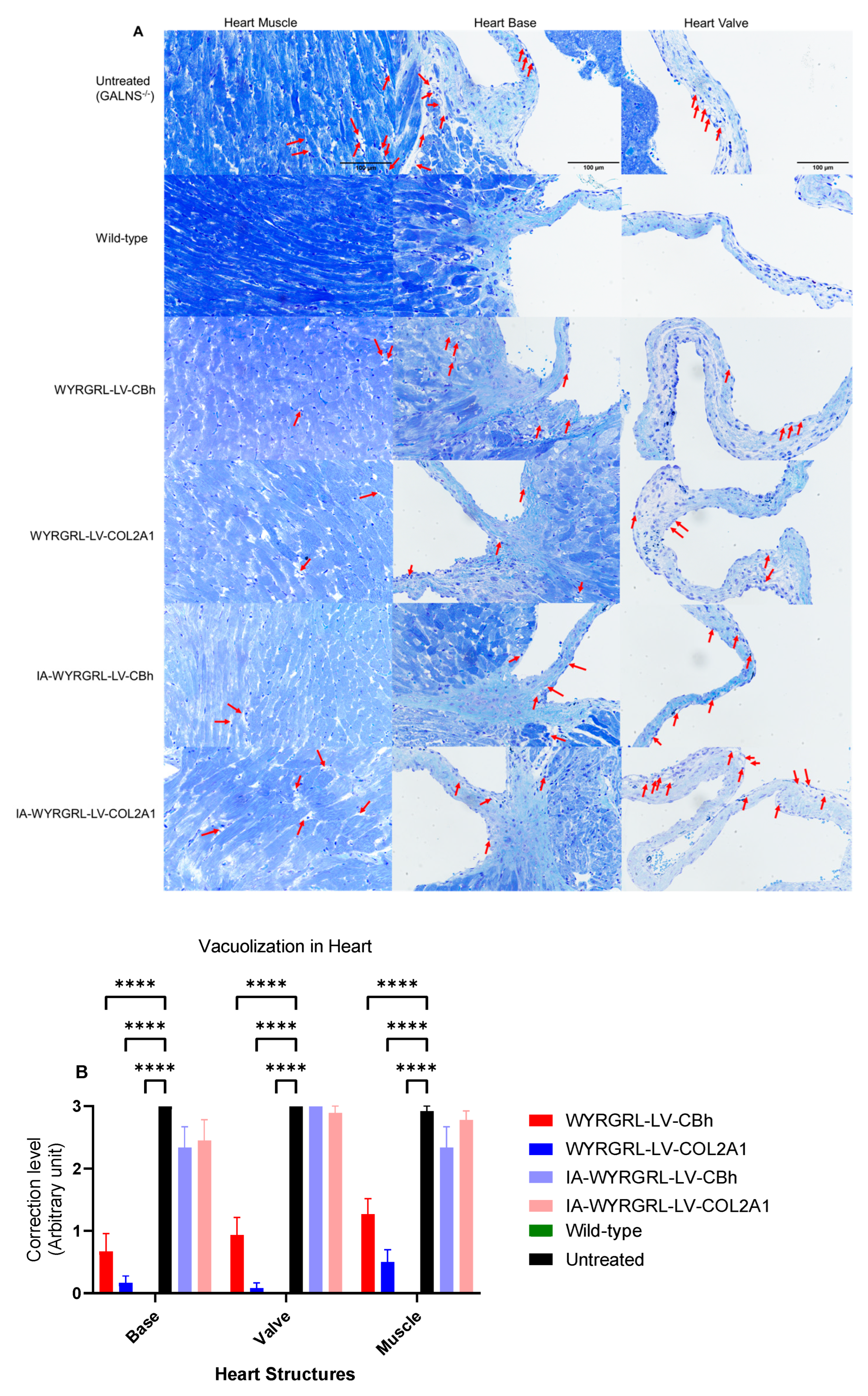

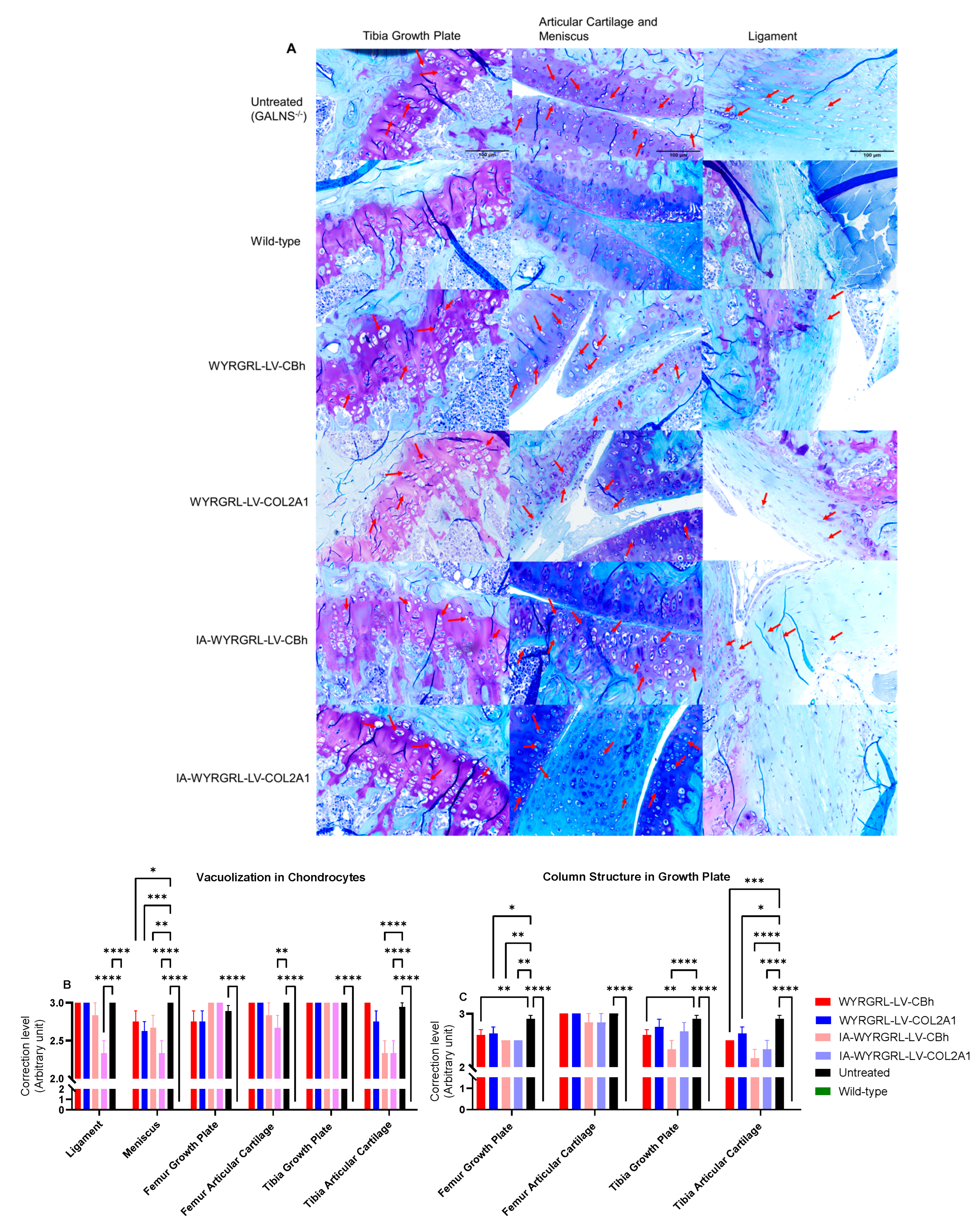

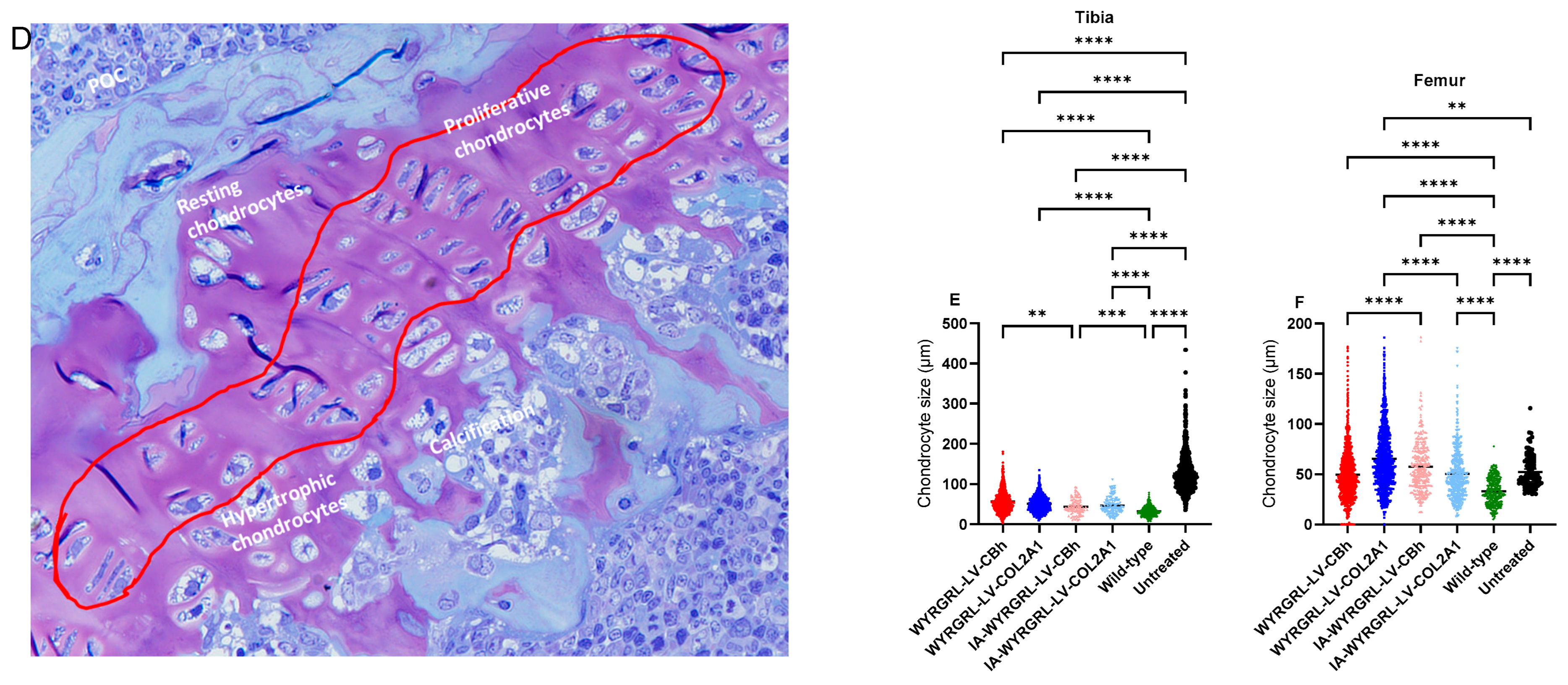

3.8. A Slight Correction Was Detected in the Heart and Bone

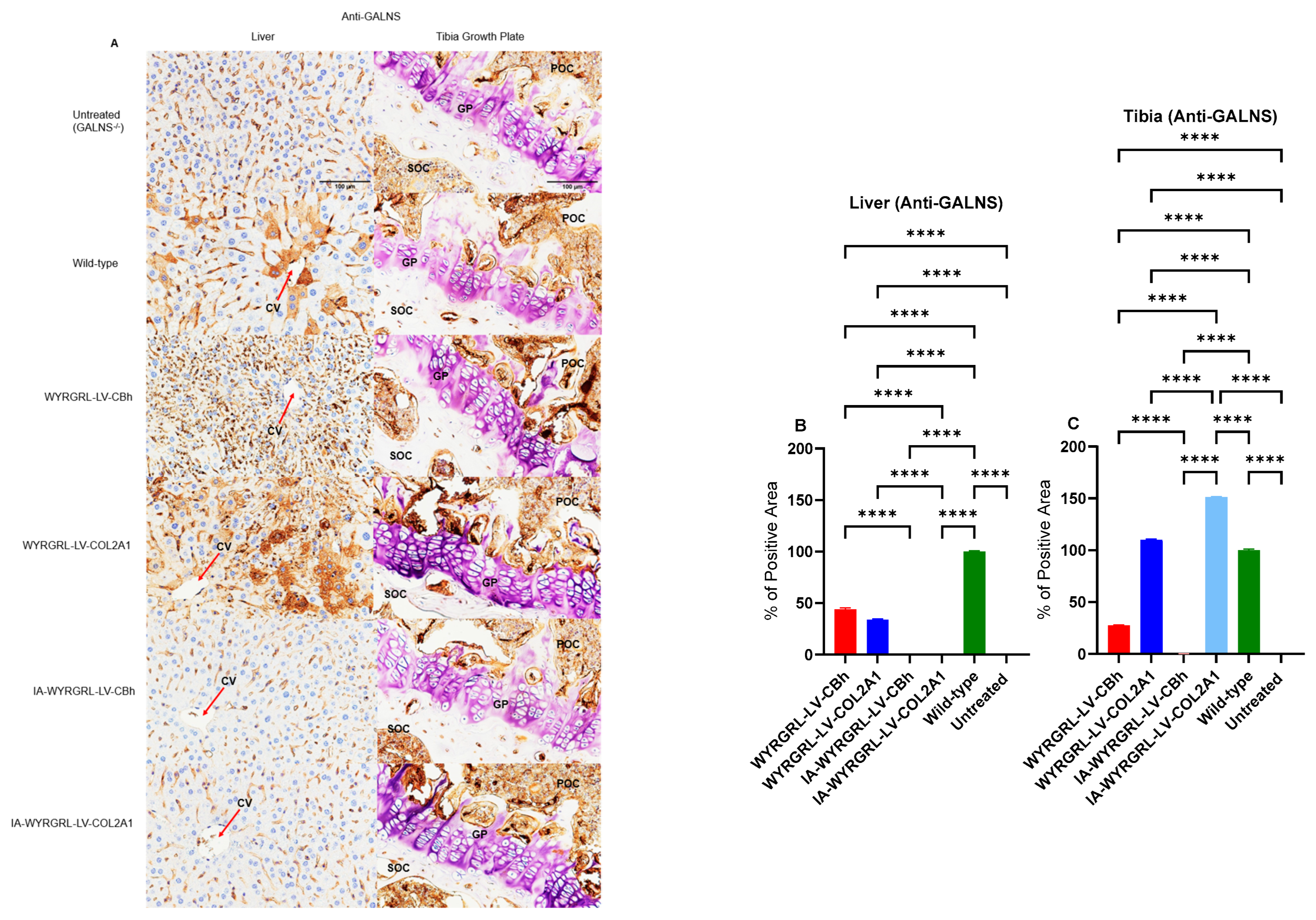

3.9. Immunohistochemical Staining Using Anti-GALNS, Anti-KS, and Anti-Collagen Antibodies

3.10. Body Weight

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MPS IVA | Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA |

| GALNS | N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfate sulfatase |

| GAGs | Glycosaminoglycans |

| KS | Keratan sulfate |

| C6S | Chondroitin-6-sulfate |

| LV | Lentiviral vectors |

| LVGT | Lentiviral gene therapy |

| VSVG | Vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein |

| IV | Intravenous |

| IA | Intraarticular |

| ERT | Enzyme replacement therapy |

| AAV | Adeno-associated virus |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| HE | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| VCN | Vector copy number |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| KO | Knockout |

| WBCs | White blood cells |

| BMCs | Bone marrow cells |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry |

| ddPCR | Digital droplet polymerase chain reaction |

| qPCR | Quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| WT | Wild-type |

| UT | Untreated |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| μCT | Micro-computational tomography |

References

- Montaño, A.M.; Tomatsu, S.; Gottesman, G.S.; Smith, M.; Orii, T. International Morquio A Registry: Clinical manifestation and natural course of Morquio A disease. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2007, 30, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, C.; Stapleton, M.; Piechnik, M.; Mason, R.W.; Mackenzie, W.G.; Yamaguchi, S.; Kobayashi, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Tomatsu, S. Effect of enzyme replacement therapy on the growth of patients with Morquio A. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 64, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigeni, M.; Rodriguez-Buritica, D.F.; Saavedra, H.; Gunther, K.A.; Hillman, P.R.; Balaguru, D.; Northrup, H. The youngest pair of siblings with Mucopolysaccharidosis type IVA to receive enzyme replacement therapy to date: A case report. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2021, 185, 3510–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.D.; Wiedemann, A.; Quinaux, T.; Battaglia-Hsu, S.F.; Mainard, L.; Froissart, R.; Bonnemains, C.; Ragot, S.; Leheup, B.; Journeau, P.; et al. 30 months follow-up of an early enzyme replacement therapy in a severe Morquio A patient: About one case. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2016, 9, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawamoto, K.; González, J.V.Á.; Piechnik, M.; Otero, F.J.; Couce, M.L.; Suzuki, Y.; Tomatsu, S. Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Management. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomatsu, S.; Sawamoto, K.; Shimada, T.; Bober, M.B.; Kubaski, F.; Yasuda, E.; Mason, R.W.; Khan, S.; Alméciga-Díaz, C.J.; Barrera, L.A.; et al. Enzyme replacement therapy for treating mucopolysaccharidosis type IVA (Morquio A syndrome): Effect and limitations. Expert Opin. Orphan Drugs 2015, 3, 1279–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomatsu, S.; Montaño, A.M.; Ohashi, A.; Gutierrez, M.A.; Oikawa, H.; Oguma, T.; Dung, V.C.; Nishioka, T.; Orii, T.; Sly, W.S. Enzyme replacement therapy in a murine model of Morquio A syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008, 17, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomatsu, S.; Montaño, A.M.; Oikawa, H.; Dung, V.C.; Hashimoto, A.; Oguma, T.; Gutiérrez, M.L.; Takahashi, T.; Shimada, T.; Orii, T.; et al. Enzyme replacement therapy in newborn mucopolysaccharidosis IVA mice: Early treatment rescues bone lesions? Mol. Genet. Metab. 2015, 114, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawamoto, K.; Karumuthil-Melethil, S.; Khan, S.; Stapleton, M.; Bruder, J.T.; Danos, O.; Tomatsu, S. Liver-Targeted AAV8 Gene Therapy Ameliorates Skeletal and Cardiovascular Pathology in a Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA Murine Model. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2020, 18, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, M.; Canepari, C.; Assanelli, S.; Merlin, S.; Borroni, E.; Starinieri, F.; Biffi, M.; Russo, F.; Fabiano, A.; Zambroni, D.; et al. GP64-pseudotyped lentiviral vectors target liver endothelial cells and correct hemophilia A mice. EMBO Mol. Med. 2024, 16, 1427–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, M.; Annoni, A.; Moalli, F.; Liu, T.; Cesana, D.; Calabria, A.; Bartolaccini, S.; Biffi, M.; Russo, F.; Visigalli, I.; et al. Phagocytosis-shielded lentiviral vectors improve liver gene therapy in nonhuman primates. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaav7325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annoni, A.; Gregori, S.; Naldini, L.; Cantore, A. Modulation of immune responses in lentiviral vector-mediated gene transfer. Cell. Immunol. 2019, 342, 103802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, C.; Wang, X.; Qiu, X.; Wu, Z.; Gao, B.; Liu, L.; Liang, G.; Zhou, H.; Yang, X.; Peng, Y.; et al. Collagen type II suppresses articular chondrocyte hypertrophy and osteoarthritis progression by promoting integrin β1−SMAD1 interaction. Bone Res. 2019, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tryfonidou, M.A.; Hazewinkel, H.A.W.; Riemers, F.M.; Brinkhof, B.; Penning, L.C.; Karperien, M. Intraspecies disparity in growth rate is associated with differences in expression of local growth plate regulators. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 299, E1044–E1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usami, Y.; Gunawardena, A.T.; Iwamoto, M.; Enomoto-Iwamoto, M. Wnt signaling in cartilage development and diseases: Lessons from animal studies. Lab. Investig. 2016, 96, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, N.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, J. Integrated analysis of COL2A1 variant data and classification of type II collagenopathies. Clin. Genet. 2019, 97, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwale, F.; Stachura, D.; Roughley, P.; Antoniou, J. Limitations of using aggrecan and type X collagen as markers of chondrogenesis in mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. J. Orthop. Res. 2006, 24, 1791–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adolphe, M. Biological Regulation of the Chondrocytes; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pulat, G.; Gökmen, O.; Özcan, Ş.; Karaman, O. Collagen binding and mimetic peptide-functionalized self-assembled peptide hydrogel enhance chondrogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2025, 113, e37786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yi, X.; Yi, W.; Jian, C.; Qi, B.; Liu, Q.; Li, Z.; Yu, A. Early diagnosis of heterotopic ossification with a NIR fluorescent probe by targeting type II collagen. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 1684–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, W.; Zhou, H.; Li, A.; Yuan, Y.; Guo, Y.; Li, P.; Qi, B.; Xiao, Y.; Yu, A.; Hu, X. A NIR-II fluorescent probe for articular cartilage degeneration imaging and osteoarthritis detection. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 1043–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, E.; Chen, H.; Qin, Z.; Guan, S.; Jiang, L.; Pang, X.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, X.; Chu, C.; et al. Harnessing Bifunctional Ferritin with Kartogenin Loading for Mesenchymal Stem Cell Capture and Enhancing Chondrogenesis in Cartilage Regeneration. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2022, 11, 2101715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; He, Z.; Peng, R.; Wu, X.; Zhu, Z.; Cui, J.; Hao, X.; Chen, A.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, P. Injectable photocrosslinking spherical hydrogel-encapsulated targeting peptide-modified engineered exosomes for osteoarthritis therapy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formica, F.A.; Barreto, G.; Zenobi-Wong, M. Cartilage-targeting dexamethasone prodrugs increase the efficacy of dexamethasone. J. Control. Release 2019, 295, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, A.; Li, X.; Sun, Z.; Sun, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, G.; Huang, D.; Xiong, H.; Yu, S.; et al. Dual-engineered cartilage-targeting extracellular vesicles derived from mesenchymal stem cells enhance osteoarthritis treatment via miR-223/NLRP3/pyroptosis axis: Toward a precision therapy. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 30, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Zhou, X.; Sang, W.; Wang, C.; Lu, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Zhu, L.; He, C.; Ma, J. Cartilage-targeting peptide-modified dual-drug delivery nanoplatform with NIR laser response for osteoarthritis therapy. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 2372–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenfluh, D.A.; Bermudez, H.; O’Neil, C.P.; Hubbell, J.A. Biofunctional polymer nanoparticles for intra-articular targeting and retention in cartilage. Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, C. Targeting the extracellular matrix for delivery of bioactive molecules to sites of arthritis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berillo, D.; Yeskendir, A.; Zharkinbekov, Z.; Raziyeva, K.; Saparov, A. Peptide-Based Drug Delivery Systems. Medicina 2021, 57, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, B.; Rintz, E.; Khan, S.; Leal, A.F.; Nidhi, F.; Tomatsu, S. In Vivo Direct Lentiviral Gene Therapy Improves Disease Pathology in a Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA Murine Model. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Kubaski, F.; Suzuki, Y.; Orii, K.; Giugliani, R.; Church, H.J.; Mason, R.W.; Dũng, V.C.; Ngoc, C.T.B.; Yamaguchi, S.; Kobayashi, H.; et al. Glycosaminoglycan levels in dried blood spots of patients with mucopolysaccharidoses and mucolipidoses. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2017, 120, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, T.; Tomatsu, S.; Mason, R.W.; Yasuda, E.; Mackenzie, W.G.; Hossain, J.; Shibata, Y.; Montaño, A.M.; Kubaski, F.; Giugliani, R.; et al. Di-sulfated Keratan Sulfate as a Novel Biomarker for Mucopolysaccharidosis II, IVA, and IVB. JIMD Rep. 2015, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celik, B.; Rintz, E.; Sansanwal, N.; Khan, S.; Bigger, B.; Tomatsu, S. Lentiviral Vector-Mediated Ex Vivo Hematopoietic Stem Cell Gene Therapy for Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA Murine Model. Hum. Gene Ther. 2024, 35, 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Chen, D.; Zuscik, M.J.; O’Keefe, R.J.; Rosier, R.N. Overexpression of Smurf2 Stimulates Endochondral Ossification Through Upregulation of β-Catenin. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2008, 23, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bond, J.E.; Kishnani, P.S.; Koeberl, D.D. Immunomodulatory, liver depot gene therapy for Pompe disease. Cell. Immunol. 2019, 342, 103737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantore, A.; Ranzani, M.; Bartholomae, C.C.; Volpin, M.; Della Valle, P.; Sanvito, F.; Sergi, L.S.; Gallina, P.; Benedicenti, F.; Bellinger, D.; et al. Liver-directed lentiviral gene therapy in a dog model of hemophilia B. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 277ra28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreja, H.; Piechaczyk, M. The effects of N-terminal insertion into VSV-G of an scFv peptide. Virol. J. 2006, 3, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Celik, B.; Saikia, S.; Khan, S.; Musini, K.S.; Tomatsu, S. Collagen Type II-Targeting Lentiviral Gene Therapy for Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2026, 48, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010042

Celik B, Saikia S, Khan S, Musini KS, Tomatsu S. Collagen Type II-Targeting Lentiviral Gene Therapy for Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2026; 48(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleCelik, Betul, Sampurna Saikia, Shaukat Khan, Krishna Sai Musini, and Shunji Tomatsu. 2026. "Collagen Type II-Targeting Lentiviral Gene Therapy for Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 48, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010042

APA StyleCelik, B., Saikia, S., Khan, S., Musini, K. S., & Tomatsu, S. (2026). Collagen Type II-Targeting Lentiviral Gene Therapy for Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 48(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010042