Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Metabolic Reprogramming in Chronic Inflammatory Diseases: Molecular Insights and Therapeutic Opportunities

Abstract

1. Introduction

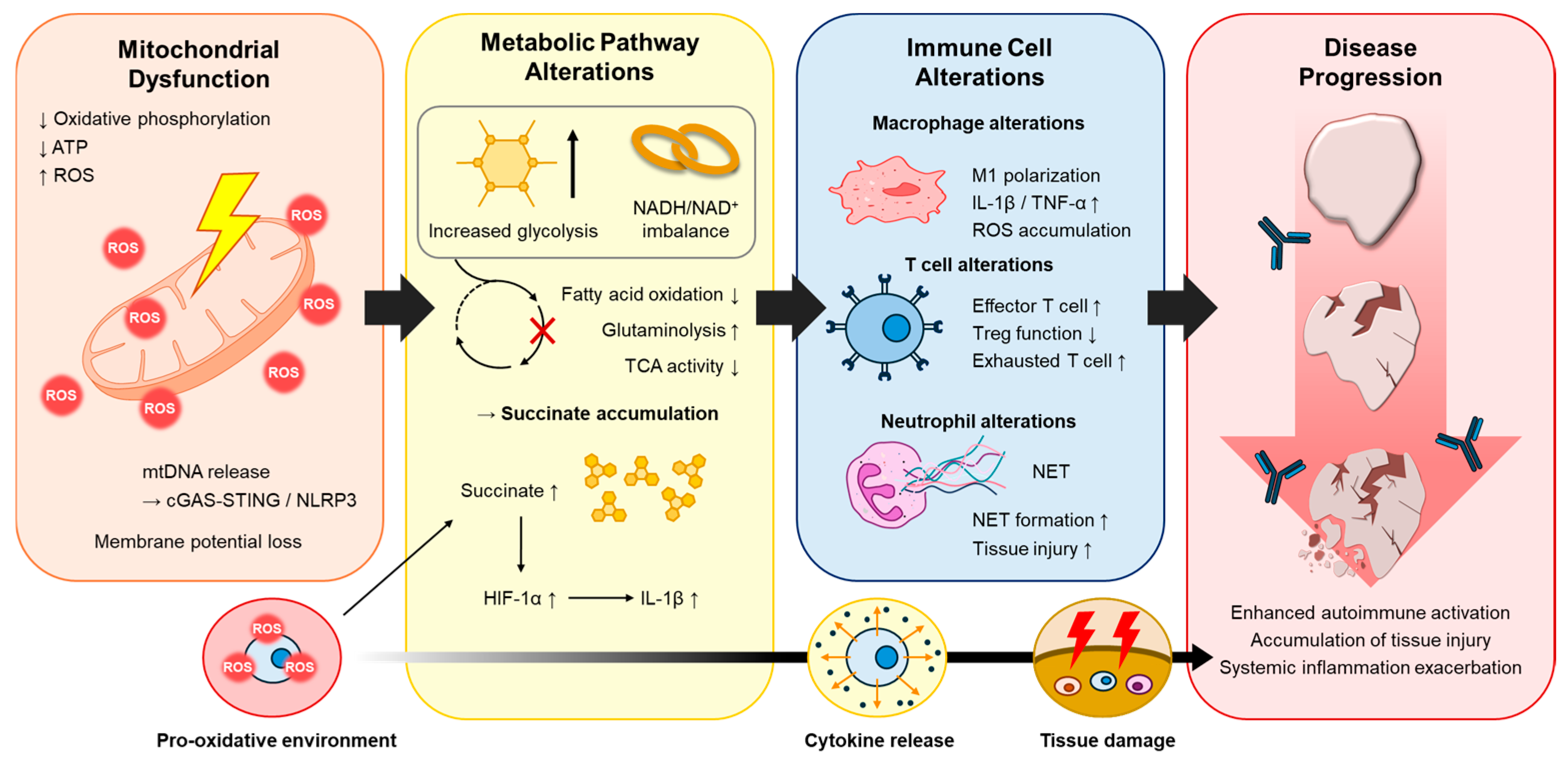

2. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Chronic Inflammation

2.1. ROS and Redox Imbalance

2.2. Mitochondrial DNA Release and Innate Immune Activation

2.3. Mitochondrial Dynamics and Mitophagy

3. Metabolic Reprogramming in Immune and Non-Immune Cells

3.1. Immuno-Metabolic Reprogramming in Macrophages and T Lymphocytes

3.2. Metabolic Adaptations in Non-Immune Cells Within Inflammatory Microenvironment

3.3. Metabolic Crosstalk in the Inflammatory Microenvironment

3.4. Therapeutic Implications of Metabolic Reprogramming

4. Therapeutic Opportunities Targeting Mitochondrial and Metabolic Pathways

4.1. Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidants and Redox Modulators

4.2. Modulators of Metabolic Checkpoints

4.3. Nutritional, Lifestyle and Precision Metabolic Interventions

4.4. Developing Technologies: Mitochondrial Transplantation, Gene Therapy and Targeted Delivery Systems

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, P.; Zhou, M.; Wang, J.; Tian, J.; Zhang, L.; Wei, Y.; Yang, F.; Xu, Y.; Wang, G. Important Role of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Immune Triggering and Inflammatory Response in Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Inflamm. Res. 2024, 17, 11631–11657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Yang, X.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, H. Metabolic Reprogramming in Immune Response and Tissue Inflammation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, 1990–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, M.D.; Orr, A.L.; Perevoshchikova, I.V.; Quinlan, C.L. The role of mitochondrial function and cellular bioenergetics in ageing and disease. Br. J. Dermatol. 2013, 169, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, J.B.; Haigis, M.C. The multifaceted contributions of mitochondria to cellular metabolism. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S.E.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondria reactive oxygen species signaling-dependent immune responses in macrophages and T cells. Immunity 2025, 58, 1904–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, Y.; Li, H.; Liao, P.; Chen, L.; Pan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, D.; Zheng, M.; Gao, J. Mitochondrial dysfunction: Mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geto, Z.; Molla, M.D.; Challa, F.; Belay, Y.; Getahun, T. Mitochondrial Dynamic Dysfunction as a Main Triggering Factor for Inflammation Associated Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases. J. Inflamm. Res. 2020, 13, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Shieh, J.S.; Qin, L.; Guo, J.J. Mitochondrial mechanisms in the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory musculoskeletal disorders. Cell Biosci. 2024, 14, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.Z.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Z.B. Mitochondrial electron transport chain, ROS generation and uncoupling (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 44, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Several lines of antioxidant defense against oxidative stress: Antioxidant enzymes, nanomaterials with multiple enzyme-mimicking activities, and low-molecular-weight antioxidants. Arch. Toxicol. 2024, 98, 1323–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Pang, Y.; Fan, X. Mitochondria in oxidative stress, inflammation and aging: From mechanisms to therapeutic advances. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Xiao, J.H. The Keap1-Nrf2 System: A Mediator between Oxidative Stress and Aging. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2021, 2021, 6635460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verza, F.A.; GC, D.A.S.; Nishimura, F.G. The impact of oxidative stress and the NRF2-KEAP1-ARE signaling pathway on anticancer drug resistance. Oncol. Res. 2025, 33, 1819–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ye, X.; Escames, G.; Lei, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Jing, T.; Yao, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, Z.; et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome: Contributions to inflammation-related diseases. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 2023, 28, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, P.; Sulejczak, D.; Kleczkowska, P.; Bukowska-Osko, I.; Kucia, M.; Popiel, M.; Wietrak, E.; Kramkowski, K.; Wrzosek, K.; Kaczynska, K. Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress—A Causative Factor and Therapeutic Target in Many Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, J.A.; Cash, N.J.; Ouyang, Y.; Morton, J.C.; Chvanov, M.; Latawiec, D.; Awais, M.; Tepikin, A.V.; Sutton, R.; Criddle, D.N. Oxidative stress alters mitochondrial bioenergetics and modifies pancreatic cell death independently of cyclophilin D, resulting in an apoptosis-to-necrosis shift. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 8032–8047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahaheikkila, M.; Peltomaa, T.; Rog, T.; Vazdar, M.; Poyry, S.; Vattulainen, I. How cardiolipin peroxidation alters the properties of the inner mitochondrial membrane? Chem. Phys. Lipids 2018, 214, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heine, K.B.; Parry, H.A.; Hood, W.R. How does density of the inner mitochondrial membrane influence mitochondrial performance? Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2023, 324, R242–R248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Yoon, J.H.; Ryu, J.H. Mitophagy: A balance regulator of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. BMB Rep. 2016, 49, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, W.; Loscalzo, J. Metabolic Responses to Reductive Stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2020, 32, 1330–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.X.; Li, C.Y.; Tao, R.; Wang, X.P.; Yan, L.J. Reductive Stress-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Cardiomyopathy. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2020, 2020, 5136957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, H.; Shen, J.; Ajjugal, Y.; Ramachandran, A.; Patel, S.S.; Lee, S.H. Sequence-specific dynamic DNA bending explains mitochondrial TFAM’s dual role in DNA packaging and transcription initiation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.A.; Carlos, D.; Ferreira, N.S.; Silva, J.F.; Zanotto, C.Z.; Zamboni, D.S.; Garcia, V.D.; Ventura, D.F.; Silva, J.S.; Tostes, R.C. Mitochondrial DNA Promotes NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Contributes to Endothelial Dysfunction and Inflammation in Type 1 Diabetes. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, Y.; Wang, T.; Huang, S.; Zhang, Z. Mitochondrial Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns and Metabolism in the Regulation of Innate Immunity. J. Innate Immun. 2023, 15, 665–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Liu, F. The cGAS-cGAMP-STING Pathway: A Molecular Link Between Immunity and Metabolism. Diabetes 2019, 68, 1099–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, B.D.; Snyder, S.H.; Bohr, V.A. Signaling by cGAS-STING in Neurodegeneration, Neuroinflammation, and Aging. Trends Neurosci. 2021, 44, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, K.; Crother, T.R.; Karlin, J.; Dagvadorj, J.; Chiba, N.; Chen, S.; Ramanujan, V.K.; Wolf, A.J.; Vergnes, L.; Ojcius, D.M.; et al. Oxidized mitochondrial DNA activates the NLRP3 inflammasome during apoptosis. Immunity 2012, 36, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xian, H.; Karin, M. Oxidized mitochondrial DNA: A protective signal gone awry. Trends Immunol. 2023, 44, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.M.; Liu, N.; Qin, Z.H.; Wang, Y. Mitochondrial-derived damage-associated molecular patterns amplify neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2022, 43, 2439–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Yang, S.; Lu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T. Research Progress on the Mechanism of Mitochondrial Autophagy in Cerebral Stroke. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 698601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, J.; Li, G.; Chen, M. The role of mitochondria-associated membranes mediated ROS on NLRP3 inflammasome in cardiovascular diseases. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 1059576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Niu, S.; Shang, M.; Li, J.; Guo, M.; Zhang, W.; Sun, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, R.; Shen, X.; et al. ROS-Drp1-mediated mitochondria fission contributes to hippocampal HT22 cell apoptosis induced by silver nanoparticles. Redox Biol. 2023, 63, 102739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Wu, L.; Wang, F.; Liu, D.; Cen, X.; Xia, H. Mitophagy Regulates Kidney Diseases. Kidney Dis. 2024, 10, 573–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Long, H.; Hou, L.; Feng, B.; Ma, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Cai, J.; Zhang, D.W.; Zhao, G. The mitophagy pathway and its implications in human diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurung, P.; Lukens, J.R.; Kanneganti, T.D. Mitochondria: Diversity in the regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Trends Mol. Med. 2015, 21, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uoselis, L.; Nguyen, T.N.; Lazarou, M. Mitochondrial degradation: Mitophagy and beyond. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 3404–3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNelis, J.C.; Olefsky, J.M. Macrophages, immunity, and metabolic disease. Immunity 2014, 41, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Min, M.; Duan, H.; Mai, J.; Liu, X. The role of macrophage and adipocyte mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of obesity. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1481312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Kitada, M.; Ogura, Y.; Koya, D. Relationship Between Autophagy and Metabolic Syndrome Characteristics in the Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 641852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Yuan, L.; Li, L.; Liu, F.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, J.; Lu, Y. Mitochondrial transfer from mesenchymal stem cells to macrophages restricts inflammation and alleviates kidney injury in diabetic nephropathy mice via PGC-1alpha activation. Stem Cells 2021, 39, 913–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, K.; Esposito, E.; Wang, X.; Terasaki, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xing, C.; Ji, X.; Lo, E.H. Transfer of mitochondria from astrocytes to neurons after stroke. Nature 2016, 535, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, J.; Sun, R.; Du, C.; Tang, Y.; Xie, C.; Li, Q.; Lin, L.; Wang, H. Mitochondrial Extracellular Vesicles: A Novel Approach to Mitochondrial Quality Control. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, E.G.; Hurst, K.E.; Riesenberg, B.P.; Kennedy, A.S.; Gandy, E.J.; Andrews, A.M.; Del Mar Alicea Pauneto, C.; Ball, L.E.; Wallace, E.D.; Gao, P.; et al. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase obstructs CD8(+) T cell lipid utilization in the tumor microenvironment. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 969–983.e910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, J.; Wu, Z. The Regulatory Role of alpha-Ketoglutarate Metabolism in Macrophages. Mediators Inflamm. 2021, 2021, 5577577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Kang, R.; Kroemer, G.; Tang, D. Ferroptosis in infection, inflammation, and immunity. J. Exp. Med. 2021, 218, e20210518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yan, Y.; Niu, F.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Su, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Qian, L.; Liu, P.; et al. Ferroptosis: A cell death connecting oxidative stress, inflammation and cardiovascular diseases. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, S.E.; O’Neill, L.A. HIF1alpha and metabolic reprogramming in inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 2016, 126, 3699–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGettrick, A.F.; O’Neill, L.A.J. The Role of HIF in Immunity and Inflammation. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 524–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, A.; Munari, F.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, R.; Scolaro, T.; Castegna, A. The Metabolic Signature of Macrophage Responses. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrocco, A.; Ortiz, L.A. Role of metabolic reprogramming in pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion from LPS or silica-activated macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 936167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, H.; Sun, W.; Yi, Q. The role of AMPK in macrophage metabolism, function and polarisation. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wculek, S.K.; Dunphy, G.; Heras-Murillo, I.; Mastrangelo, A.; Sancho, D. Metabolism of tissue macrophages in homeostasis and pathology. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2022, 19, 384–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.Y.; Mauro, C. Similarities in the Metabolic Reprogramming of Immune System and Endothelium. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Miao, C. Metabolic reprogram and T cell differentiation in inflammation: Current evidence and future perspectives. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Carbonell, R.; Divakaruni, A.S.; Lodi, A.; Vicente-Suarez, I.; Saha, A.; Cheroutre, H.; Boss, G.R.; Tiziani, S.; Murphy, A.N.; Guma, M. Critical Role of Glucose Metabolism in Rheumatoid Arthritis Fibroblast-like Synoviocytes. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016, 68, 1614–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Garcia, S.; Moreno-Altamirano, M.M.; Prado-Garcia, H.; Sanchez-Garcia, F.J. Lactate Contribution to the Tumor Microenvironment: Mechanisms, Effects on Immune Cells and Therapeutic Relevance. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaviano, A.; Foo, A.S.C.; Lam, H.Y.; Yap, K.C.H.; Jacot, W.; Jones, R.H.; Eng, H.; Nair, M.G.; Makvandi, P.; Geoerger, B.; et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling transduction pathway and targeted therapies in cancer. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rath, E.; Haller, D. Intestinal epithelial cell metabolism at the interface of microbial dysbiosis and tissue injury. Mucosal Immunol. 2022, 15, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, C.; McLean, M.H.; Durum, S.K. Cytokine Tuning of Intestinal Epithelial Function. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Shen, C.; Zeng, X.; Sun, L.; Luo, F.; Wan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Hou, Y.; Wang, W.; et al. Energy metabolism and the intestinal barrier: Implications for understanding and managing intestinal diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1515364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozkowiak, M.; Niebora, J.; Domagala, D.; Data, K.; Partynska, A.; Kulus, M.; Kotrych, K.; Podralska, M.; Gorska, A.; Chwilkowska, A.; et al. New insights into endothelial cell physiology and pathophysiology. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 190, 118415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, S.W.S.; Shi, Y. The glycolytic process in endothelial cells and its implications. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2022, 43, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wik, J.A.; Phung, D.; Kolan, S.; Haraldsen, G.; Skalhegg, B.S.; Hol Fosse, J. Inflammatory activation of endothelial cells increases glycolysis and oxygen consumption despite inhibiting cell proliferation. FEBS Open Bio 2021, 11, 1719–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matiuto, N.; Applewhite, B.; Habash, N.; Martins, A.; Wang, B.; Jiang, B. Harnessing Mitochondrial Transplantation to Target Vascular Inflammation in Cardiovascular Health. JACC Basic. Transl. Sci. 2025, 10, 101331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Guo, C.; Zhang, L. The role of metabolite sensors in metabolism-immune interaction: New targets for immune modulation. Clin. Transl. Med. 2025, 15, e70294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Liu, C.H.; Lei, M.; Zeng, Q.; Li, L.; Tang, H.; Zhang, N. Metabolic regulation of the immune system in health and diseases: Mechanisms and interventions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairley, L.H.; Das, S.; Dharwal, V.; Amorim, N.; Hegarty, K.J.; Wadhwa, R.; Mounika, G.; Hansbro, P.M. Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidants as a Therapeutic Strategy for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Zeng, Z.L.; Yang, S.; Li, A.; Zu, X.; Liu, J. Mitochondrial Stress in Metabolic Inflammation: Modest Benefits and Full Losses. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022, 2022, 8803404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, J.K.; Jorwal, K.; Singh, K.K.; Han, S.S.; Bhaskar, R.; Ghosh, S. The Potential of Mitochondrial Therapeutics in the Treatment of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Aging. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 6748–6763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, H.; Wang, J. Metabolism and Chronic Inflammation: The Links Between Chronic Heart Failure and Comorbidities. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 650278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A.; Pollock, C.A.; Huang, C. Mitochondria-targeting therapeutic strategies for chronic kidney disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2025, 231, 116669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, R.K.; Kolishetti, N.; Dhar, S. Targeted nanoparticles in mitochondrial medicine. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2015, 7, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Li, X.M.; Wei, L.S.; Ye, J.F. Advancements in mitochondrial-targeted nanotherapeutics: Overcoming biological obstacles and optimizing drug delivery. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1451989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mechanistic Process | Molecular Regulators | Downstream Effect | Representative Diseases | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitochondrial ROS overproduction | Complex I/III of ETC, NRF2–KEAP1, SOD2, PRDX3, GPX4 | Oxidative stress, activation of NF-κB and MAPK signaling | Rheumatoid arthritis, COPD, SLE | [9,10] |

| mtDNA release | TFAM, Bax/Bak, VDAC, cGAS–STING, TLR9 | Activation of type I IFN and inflammasome signaling | Sepsis, autoimmune disorders | [28,30] |

| Defective mitophagy | PINK1–Parkin, BNIP3/NIX, DRP1, MFN2 | Accumulation of damaged mitochondria, NLRP3 activation | Atherosclerosis, type 2 diabetes | [31,35] |

| Altered mitochondrial dynamics | DRP1, OPA1, MFN1/2 | Fragmentation, loss of membrane potential, ROS amplification | Neuroinflammation, metabolic syndrome | [8,32] |

| Metabolic Pathway | Regulatory Signaling Pathway | Functional Outcome | Cellular Targets | Inflammatory Context | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycolysis | HIF1α with succinate pathway; PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway | Rapid ATP generation, IL-1β production, pro-inflammatory phenotype | M1 macrophages, activated T cells, fibroblasts | Rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis | [49,54,55] |

| Fatty acid oxidation (FAO) | AMPK–PGC1β–PPARγ regulatory pathway; SIRT1 signaling | Mitochondrial biogenesis, anti-inflammatory polarization | M2 macrophages, Tregs, endothelial cells | Atherosclerosis, fibrosis | [2,50] |

| Amino acid metabolism | mTOR–ATF4–SIRT3 signaling cascade | T cell activation, oxidative balance | Effector T cells, epithelial cells | IBD, chronic airway inflammation | [53,54] |

| TCA cycle intermediates | Itaconate with NRF2 pathway; Succinate with HIF1α pathway | Anti- vs. pro-inflammatory metabolic switching | Macrophages, dendritic cells | Systemic inflammation, metabolic disease | [65,66] |

| Lactate metabolism | LDHA, HIF1α, and GPR81 signaling network | Histone lactylation, angiogenesis | Fibroblasts, endothelial cells | Tumor-associated inflammation, synovitis | [56,58,59] |

| Therapeutic Category | Primary Molecular Target | Mechanistic Action | Experimental/Clinical Evidence | Translational Challenges | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants | MitoQ, SS-31, CoQ10 analogs; NRF2 and SOD2 | Reduce mtROS, stabilize cardiolipin, restore ΔΨm | Improved mitochondrial function and reduced cytokine release in COPD and cardiovascular models | Limited targeting specificity; maintaining physiological ROS balance | [6,67] |

| AMPK activators/mTOR inhibitors | AMPK, mTORC1, SIRT3 | Restore mitochondrial biogenesis, suppress glycolysis, promote oxidative metabolism | Metformin and rapamycin reduced inflammatory markers in preclinical and clinical studies | Systemic metabolic effects; dose-dependent adaptation | [68,69] |

| NAD+ boosters and Sirtuin activators | SIRT1/3, PGC1α | Enhance oxidative metabolism, improve redox balance | Nicotinamide riboside improved mitochondrial parameters in metabolic inflammation models | Long-term efficacy and tissue selectivity | [2,66] |

| Lifestyle/nutritional interventions | Caloric restriction, ketogenic diet, exercise | Enhance mitophagy and mitochondrial turnover; reduce systemic IL-6 and TNF-α | Clinical and animal studies show reduced inflammatory cytokines and improved mitochondrial function | Variability in adherence and metabolic heterogeneity | [66,70] |

| Gene or mitochondrial therapies | PGC1α, NRF2, PINK1, Parkin | Restore mitochondrial quality control; reprogram cellular metabolism at its source | Mitochondrial transplantation and gene modulation improved outcomes in ischemic and metabolic disease models | Delivery specificity, immune response, long-term stability | [1,71,72] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, M.E.; Lim, Y.; Lee, J.S. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Metabolic Reprogramming in Chronic Inflammatory Diseases: Molecular Insights and Therapeutic Opportunities. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 1042. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121042

Kim ME, Lim Y, Lee JS. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Metabolic Reprogramming in Chronic Inflammatory Diseases: Molecular Insights and Therapeutic Opportunities. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2025; 47(12):1042. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121042

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Mi Eun, Yeeun Lim, and Jun Sik Lee. 2025. "Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Metabolic Reprogramming in Chronic Inflammatory Diseases: Molecular Insights and Therapeutic Opportunities" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 47, no. 12: 1042. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121042

APA StyleKim, M. E., Lim, Y., & Lee, J. S. (2025). Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Metabolic Reprogramming in Chronic Inflammatory Diseases: Molecular Insights and Therapeutic Opportunities. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 47(12), 1042. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121042