Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria and Biochar as Drought Defense Tools: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanisms and Future Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Impact of Drought on Plant Function and Survival

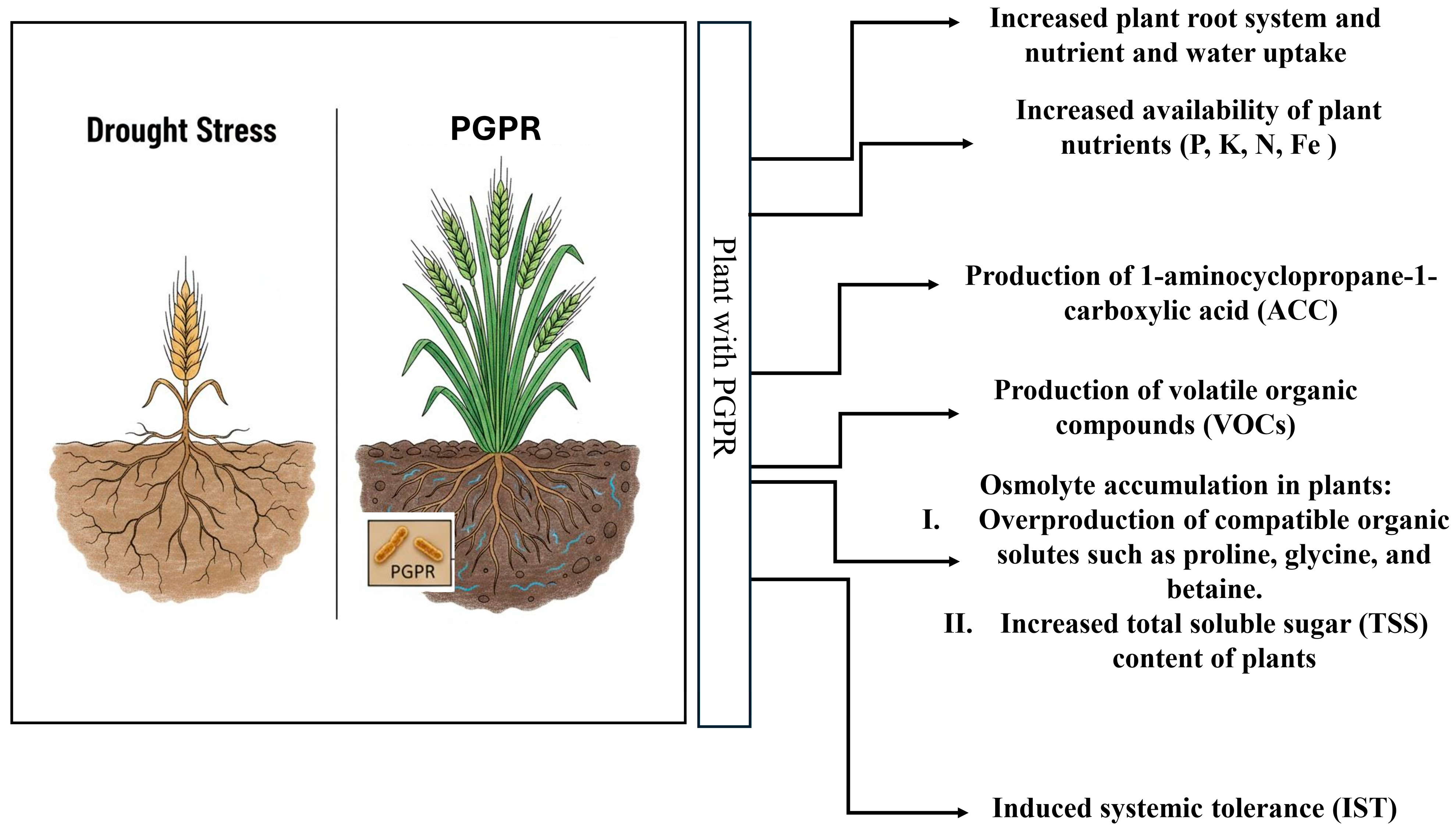

4. PGPR and Drought Tolerance

4.1. Improved Nutrient Absorption

4.2. Alteration in Phytohormone Levels

4.3. Emission of Volatile Organic Compounds

4.4. Synthesis of Exopolysaccharides

4.5. Osmotic Balance Adjustment

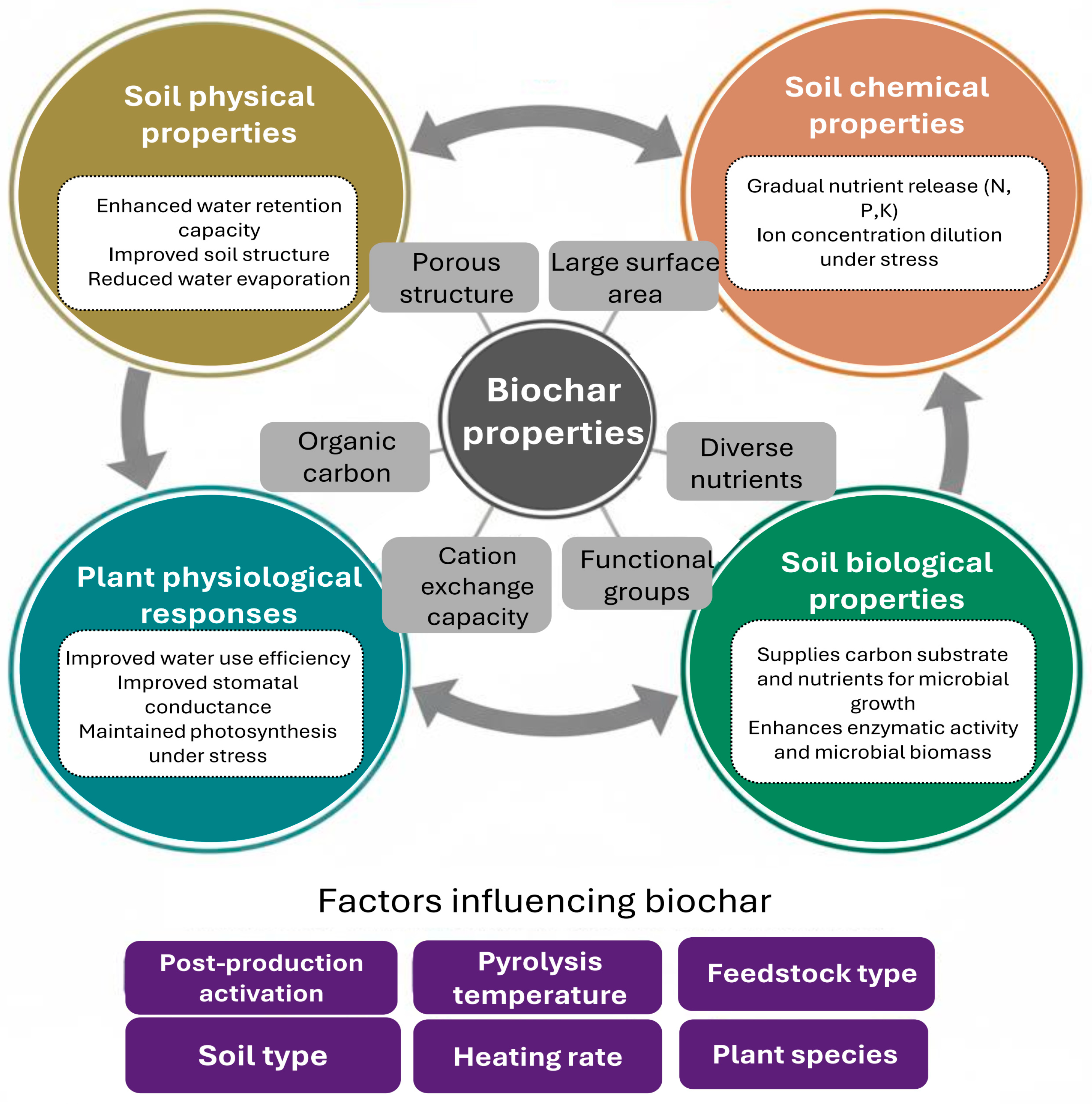

5. Drought Regulation by the Application of Biochar

6. Biochar as a Habitat for PGPR

7. Co-Application of Biochar and PGPR

8. Mechanisms of Enhanced Drought Tolerance in Plants Co-Supplied with Biochar and PGPR

9. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Suárez, R.; Wong, A.; Ramírez, M.; Barraza, A.; Del, M.; Orozco, C.; Cevallos, M.A.; Lara, M.; Hernández, G.; Iturriaga, G. Improvement of Drought Tolerance and Grain Yield in Common Bean by Overexpressing Trehalose-6-Phosphate Synthase in Rhizobia. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2008, 21, 958–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borjas-Ventura, R.; Ferraudo, A.S.; Martínez, C.A.; Gratão, P.L. Global Warming: Antioxidant Responses to Deal with Drought and Elevated Temperature in Stylosanthes Capitata, a Forage Legume. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2020, 206, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delshadi, S.; Ebrahimi, M.; Shirmohammadi, E. Effectiveness of Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria on Bromus Tomentellus Boiss Seed Germination, Growth and Nutrients Uptake under Drought Stress. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2017, 113, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinocur, B.; Altman, A. Recent Advances in Engineering Plant Tolerance to Abiotic Stress: Achievements and Limitations. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2005, 16, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Polanco, M.; Sánchez-Romera, B.; Aroca, R.; Asins, M.J.; Declerck, S.; Dodd, I.C.; Martínez-Andújar, C.; Albacete, A.; Ruiz-Lozano, J.M. Exploring the Use of Recombinant Inbred Lines in Combination with Beneficial Microbial Inoculants (AM Fungus and PGPR) to Improve Drought Stress Tolerance in Tomato. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2016, 131, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golldack, D.; Li, C.; Mohan, H.; Probst, N. Tolerance to Drought and Salt Stress in Plants: Unraveling the Signaling Networks. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M. Inducing Drought Tolerance in Plants: Recent Advances. Biotechnol. Adv. 2010, 28, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushal, M. Portraying Rhizobacterial Mechanisms in Drought Tolerance. In PGPR Amelioration in Sustainable Agriculture; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 195–216. [Google Scholar]

- Glick, B.R. Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria: Mechanisms and Applications. Scientifica 2012, 2012, 963401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar-Ul-Hye, M.; Danish, S.; Abbas, M.; Ahmad, M.; Munir, T.M. ACC Deaminase Producing PGPR Bacillus Amyloliquefaciens and Agrobacterium Fabrum along with Biochar Improve Wheat Productivity under Drought Stress. Agronomy 2019, 9, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, T.; Rizwan, M.; Ali, S.; Zia-ur-Rehman, M.; Farooq Qayyum, M.; Abbas, F.; Hannan, F.; Rinklebe, J.; Sik Ok, Y. Effect of Biochar on Cadmium Bioavailability and Uptake in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Grown in a Soil with Aged Contamination. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 140, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiaz, K.; Danish, S.; Raza Shah, M.H.; Niaz, S. Drought Impact on Pb/Cd Toxicity Remediated by Biochar in Brassica Campestris. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2014, 14, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, M.F.A.; Mohamed, H.I.; Abideen, Z.; Sheteiwy, M.S.; Eissa, M.A.; Abdel Latef, A.A.H. Biochar Amendments and Drought Tolerance of Plants. In Biochar in Mitigating Abiotic Stress in Plants; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 229–246. ISBN 9780443241376. [Google Scholar]

- Danish, S.; Zafar-ul-Hye, M.; Fahad, S.; Saud, S.; Brtnicky, M.; Hammerschmiedt, T.; Datta, R. Drought Stress Alleviation by ACC Deaminase Producing Achromobacter Xylosoxidans and Enterobacter Cloacae, with and without Timber Waste Biochar in Maize. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdomo, J.A.; Capó-Bauçà, S.; Carmo-Silva, E.; Galmés, J. Rubisco and Rubisco Activase Play an Important Role in the Biochemical Limitations of Photosynthesis in Rice, Wheat, and Maize under High Temperature and Water Deficit. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappero, J.; Cappellari, L.d.R.; Sosa Alderete, L.G.; Palermo, T.B.; Banchio, E. Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria Improve the Antioxidant Status in Mentha Piperita Grown under Drought Stress Leading to an Enhancement of Plant Growth and Total Phenolic Content. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 139, 111553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Gogoi, N.; Barthakur, S.; Baroowa, B.; Bharadwaj, N.; Alghamdi, S.S.; Siddique, K.H.M. Drought Stress in Grain Legumes during Reproduction and Grain Filling. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2017, 203, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guangyu, Z.; Jiangwei, W.; Haorui, Z.; Gang, F.; Zhenxi, S. Comparative Study of the Impact of Drought Stress on P. centrasiaticum at the Seedling Stage in Tibet. J. Resour. Ecol. 2020, 11, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Galván, A.E.; Cortés-Patiño, S.; Romero-Perdomo, F.; Uribe-Vélez, D.; Bashan, Y.; Bonilla, R.R. Proline Accumulation and Glutathione Reductase Activity Induced by Drought-Tolerant Rhizobacteria as Potential Mechanisms to Alleviate Drought Stress in Guinea Grass. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 147, 103367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romdhane, L.; Awad, Y.M.; Radhouane, L.; Dal Cortivo, C.; Barion, G.; Panozzo, A.; Vamerali, T. Wood Biochar Produces Different Rates of Root Growth and Transpiration in Two Maize Hybrids (Zea mays L.) under Drought Stress. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2019, 65, 846–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liang, K.; Cui, B.; Hou, J.; Rosenqvist, E.; Fang, L.; Liu, F. Incorporating the Temperature Responses of Stomatal and Non-Stomatal Limitations to Photosynthesis Improves the Predictability of the Unified Stomatal Optimization Model for Wheat under Heat Stress. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2025, 362, 110381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisp, P.A.; Ganguly, D.; Eichten, S.R.; Borevitz, J.O.; Pogson, B.J. Reconsidering Plant Memory: Intersections between Stress Recovery, RNA Turnover, and Epigenetics. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1501340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, N.; Ilyas, N.; Mashwani, Z.u.R.; Hayat, R.; Yasmin, H.; Noureldeen, A.; Ahmad, P. Synergistic Effects of Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria and Silicon Dioxide Nano-Particles for Amelioration of Drought Stress in Wheat. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 166, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanta, N.; Schwinghamer, T.; Backer, R.; Allaire, S.E.; Teshler, I.; Vanasse, A.; Whalen, J.; Baril, B.; Lange, S.; MacKay, J.; et al. Biochar and Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria Effects on Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum Cv. Cave-in-Rock) for Biomass Production in Southern Québec Depend on Soil Type and Location. Biomass Bioenergy 2016, 95, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthymiou, A.; Grønlund, M.; Müller-Stöver, D.S.; Jakobsen, I. Augmentation of the Phosphorus Fertilizer Value of Biochar by Inoculation of Wheat with Selected Penicillium Strains. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 116, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parastesh, F.; Alikhani, H.A.; Etesami, H. Vermicompost Enriched with Phosphate–Solubilizing Bacteria Provides Plant with Enough Phosphorus in a Sequential Cropping under Calcareous Soil Conditions. J. Clean Prod. 2019, 221, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rékási, M.; Szili-Kovács, T.; Takács, T.; Bernhardt, B.; Puspán, I.; Kovács, R.; Kutasi, J.; Draskovits, E.; Molnár, S.; Molnár, M.; et al. Improving the Fertility of Sandy Soils in the Temperate Region by Combined Biochar and Microbial Inoculant Treatments. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2019, 65, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaib, S.; Zubair, A.; Abbas, S.; Hussain, J.; Ahmad, I.; Shakeel, S.N. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) Reduce Adverse Effects of Salinity and Drought Stresses by Regulating Nutritional Profile of Barley. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2023, 2023, 7261784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, N.; Armada, E.; Duque, E.; Roldán, A.; Azcón, R. Contribution of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and/or Bacteria to Enhancing Plant Drought Tolerance under Natural Soil Conditions: Effectiveness of Autochthonous or Allochthonous Strains. J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 174, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, A.; Manghwar, H.; Shaban, M.; Khan, A.H.; Akbar, A.; Ali, U.; Ali, E.; Fahad, S. Phytohormones Enhanced Drought Tolerance in Plants: A Coping Strategy. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 33103–33118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Castro, R.; Campos-García, J.; López-Bucio, J. Pseudomonas Putida and Pseudomonas Fluorescens Influence Arabidopsis Root System Architecture Through an Auxin Response Mediated by Bioactive Cyclodipeptides. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 39, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, A.W.; Bartel, B. Auxin: Regulation, Action, and Interaction. Ann. Bot. 2005, 95, 707–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaepen, S.; Vanderleyden, J. Auxin and Plant-Microbe Interactions. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a001438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, P.; Alves, A.; Silveira, P.; Sá, C.; Fidalgo, C.; Freitas, R.; Figueira, E. Bacteria from Nodules of Wild Legume Species: Phylogenetic Diversity, Plant Growth Promotion Abilities and Osmotolerance. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 645, 1094–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creus, C.M.; Graziano, M.; Casanovas, E.M.; Pereyra, M.A.; Simontacchi, M.; Puntarulo, S.; Barassi, C.A.; Lamattina, L. Nitric Oxide Is Involved in the Azospirillum Brasilense-Induced Lateral Root Formation in Tomato. Planta 2005, 221, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Li, Z.; Yu, D. Bacillus Megaterium Strain XTBG34 Promotes Plant Growth by Producing 2-Pentylfuran. J. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, H.A.S.; Gu, Q.; Wu, H.; Raza, W.; Hanif, A.; Wu, L.; Colman, M.V.; Gao, X. Plant Growth Promotion by Volatile Organic Compounds Produced by Bacillus Subtilis SYST2. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, R.; Rokem, J.S.; Ilangumaran, G.; Lamont, J.; Praslickova, D.; Ricci, E.; Subramanian, S.; Smith, D.L. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria: Context, Mechanisms of Action, and Roadmap to Commercialization of Biostimulants for Sustainable Agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolli, E.; Marasco, R.; Vigani, G.; Ettoumi, B.; Mapelli, F.; Deangelis, M.L.; Gandolfi, C.; Casati, E.; Previtali, F.; Gerbino, R.; et al. Improved Plant Resistance to Drought Is Promoted by the Root-Associated Microbiome as a Water Stress-Dependent Trait. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 17, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borlee, B.R.; Goldman, A.D.; Murakami, K.; Samudrala, R.; Wozniak, D.J.; Parsek, M.R. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Uses a Cyclic-Di-GMP-Regulated Adhesin to Reinforce the Biofilm Extracellular Matrix. Mol. Microbiol. 2010, 75, 827–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hong, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, N.; Jiang, S.; Yao, Z.; Zhu, M.; Ding, J.; Li, C.; Xu, W.; et al. Rhizosheath Formation and Its Role in Plant Adaptation to Abiotic Stress. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcillo, R.J.L.; Manzanera, M. The Effects of Plant-Associated Bacterial Exopolysaccharides on Plant Abiotic Stress Tolerance. Metabolites 2021, 11, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjum, S.A.; Ashraf, U.; Tanveer, M.; Khan, I.; Hussain, S.; Shahzad, B.; Zohaib, A.; Abbas, F.; Saleem, M.F.; Ali, I.; et al. Drought Induced Changes in Growth, Osmolyte Accumulation and Antioxidant Metabolism of Three Maize Hybrids. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szablińska-Piernik, J.; Lahuta, L.B. Metabolite Profiling of Semi-Leafless Pea (Pisum sativum L.) under Progressive Soil Drought and Subsequent Re-Watering. J. Plant Physiol. 2021, 256, 153314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, S.; Hayat, Q.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Wani, A.S.; Pichtel, J.; Ahmad, A. Role of Proline under Changing Environments: A Review. Plant Signal Behav. 2012, 7, 1456–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Beltagi, H.S.; Mohamed, H.I.; Sofy, M.R. Role of Ascorbic Acid, Glutathione and Proline Applied as Singly or in Sequence Combination in Improving Chickpea Plant through Physiological Change and Antioxidant Defense under Different Levels of Irrigation Intervals. Molecules 2020, 25, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WANG, Y.; LI, W.; DU, B.; LI, H. Effect of Biochar Applied with Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) on Soil Microbial Community Composition and Nitrogen Utilization in Tomato. Pedosphere 2021, 31, 872–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Huang, K.; Batool, M.; Idrees, F.; Afzal, R.; Haroon, M.; Noushahi, H.A.; Wu, W.; Hu, Q.; Lu, X.; et al. Versatile Roles of Polyamines in Improving Abiotic Stress Tolerance of Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1003155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitarafan, Z.; Liu, F.; Andreasen, C. The Effect of Different Biochars on the Growth and Water Use Efficiency of Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.). J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2020, 206, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Akhtar, S.S.; Li, L.; Fu, Q.; Li, Q.; Naeem, M.A.; He, X.; Zhang, Z.; Jacobsen, S.E. Biochar Mitigates Combined Effects of Drought and Salinity Stress in Quinoa. Agronomy 2020, 10, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, S.; Kour, N.; Manhas, S.; Zahid, S.; Wani, O.A.; Sharma, V.; Wijaya, L.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Alsahli, A.A.; El-Serehy, H.A.; et al. Biochar as a Tool for Effective Management of Drought and Heavy Metal Toxicity. Chemosphere 2021, 271, 129458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, A.; Sokołowska, Z.; Boguta, P. Biochar Physicochemical Properties: Pyrolysis Temperature and Feedstock Kind Effects. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 19, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtaza, G.; Ahmed, Z.; Usman, M.; Tariq, W.; Ullah, Z.; Shareef, M.; Iqbal, H.; Waqas, M.; Tariq, A.; Wu, Y.; et al. Biochar Induced Modifications in Soil Properties and Its Impacts on Crop Growth and Production. J. Plant Nutr. 2021, 44, 1677–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adejumo, S.A.; Arowo, D.O.; Ogundiran, M.B.; Srivastava, P. Biochar in Combination with Compost Reduced Pb Uptake and Enhanced the Growth of Maize in Lead (Pb)-Contaminated Soil Exposed to Drought Stress. J. Crop Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 23, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abideen, Z.; Koyro, H.W.; Huchzermeyer, B.; Ansari, R.; Zulfiqar, F.; Gul, B. Ameliorating Effects of Biochar on Photosynthetic Efficiency and Antioxidant Defence of Phragmites Karka under Drought Stress. Plant Biol. 2020, 22, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, Y.; Iqbal, S.; Jabeen, K.; Shahzad, S.; Jahan, S.; Rasul, F. Effect of Biochar Application on Seed Germination and Seedling Growth of Glycine max (L.) Merr. Under Drought Stress. Pak. J. Bot. 2017, 49, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, V.; Hauggaard-Nielsen, H.; Petersen, C.T.; Mikkelsen, T.N.; Müller-Stöver, D. Effects of Gasification Biochar on Plant-Available Water Capacity and Plant Growth in Two Contrasting Soil Types. Soil Tillage Res. 2016, 161, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yang, S.H.; Jiang, Z.W.; Ding, J.; Sun, X. Biochar as a Tool to Reduce Environmental Impacts of Nitrogen Loss in Water-Saving Irrigation Paddy Field. J. Clean Prod. 2021, 290, 125811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palansooriya, K.N.; Wong, J.T.F.; Hashimoto, Y.; Huang, L.; Rinklebe, J.; Chang, S.X.; Bolan, N.; Wang, H.; Ok, Y.S. Response of Microbial Communities to Biochar-Amended Soils: A Critical Review. Biochar 2019, 1, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P.; Jha, P.N. The Multifarious PGPR Serratia Marcescens CDP-13 Augments Induced Systemic Resistance and Enhanced Salinity Tolerance of Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boretti, A.; Rosa, L. Reassessing the Projections of the World Water Development Report. NPJ Clean Water 2019, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, A. Soil and Biochar: Attributes and Actions of Biochar for Reclamation of Soil and Mitigation of Soil Borne Plant Pathogens. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 1924–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, L.; Hussain, S.; Shahid, M.; Mahmood, F.; Ali, H.M.; Malik, M.; Sanaullah, M.; Zahid, Z.; Shahzad, T. Co-Applied Biochar and Drought Tolerant PGPRs Induced More Improvement in Soil Quality and Wheat Production than Their Individual Applications under Drought Conditions. PeerJ 2024, 12, e18171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.R.; Jahan, I.; Mou, S.J.; Hasin, F.; Angon, P.B.; Sultana, R.; Mazumder, B.; Sakil, A. Function of Biochar: Alleviation of Heat Stress in Plants and Improvement of Soil Microbial Communities. Phyton Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 94, 1177–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Jiang, Q.; Akhtar, K.; Luo, R.; Jiang, M.; He, B.; Wen, R. Biochar and Manure Co-Application Improves Soil Health and Rice Productivity through Microbial Modulation. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helaoui, S.; Boughattas, I.; Mkhinini, M.; Ghazouani, H.; Jabnouni, H.; Kribi-Boukhris, S.E.; Marai, B.; Slimani, D.; Arfaoui, Z.; Banni, M. Biochar Application Mitigates Salt Stress on Maize Plant: Study of the Agronomic Parameters, Photosynthetic Activities and Biochemical Attributes. Plant Stress 2023, 9, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumawat, K.C.; Sharma, B.; Nagpal, S.; Kumar, A.; Tiwari, S.; Nair, R.M. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria: Salt Stress Alleviators to Improve Crop Productivity for Sustainable Agriculture Development. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1101862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, E.; Kim, K.H.; Kwon, E.E. Biochar as a Tool for the Improvement of Soil and Environment. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1324533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libutti, A.; Francavilla, M.; Monteleone, M. Hydrological Properties of a Clay Loam Soil as Affected by Biochar Application in a Pot Experiment. Agronomy 2021, 11, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Peng, Y.; Lin, L.; Zhang, D.; Ma, L.; Jiang, L.; Li, Y.; He, T.; Wang, Z. Drivers of Biochar-Mediated Improvement of Soil Water Retention Capacity Based on Soil Texture: A Meta-Analysis. Geoderma 2023, 437, 116591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Niu, W.; Luo, H. Effect of Biochar Amendment on the Growth and Photosynthetic Traits of Plants Under Drought Stress: A Meta-Analysis. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtaza, G.; Ahmed, Z.; Iqbal, R.; Deng, G. Biochar from Agricultural Waste as a Strategic Resource for Promotion of Crop Growth and Nutrient Cycling of Soil under Drought and Salinity Stress Conditions: A Comprehensive Review with Context of Climate Change. J. Plant Nutr. 2025, 48, 1832–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; De Almeida Moreira, B.R.; Bai, Y.; Nadar, C.G.; Feng, Y.; Yadav, S. Assessing Biochar’s Impact on Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Microbial Biomass, and Enzyme Activities in Agricultural Soils through Meta-Analysis and Machine Learning. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 963, 178541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwaltney, L.; Brye, K.R.; Lunga, D.D.; Roberts, T.L.; Fernandes, S.B.; Daniels, M.B. Biochar Type and Rate Effects on Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Furrow-Irrigated Rice. Agrosystems Geosci. Environ. 2025, 8, e70186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Yang, R.; Fu, Y.; Zhu, B. Superior Properties of Biochar Contribute to Soil Carbon Sequestration and Climate Change Mitigation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, A.; Bucura, F.; Botoran, O.R.; Radu, G.L.; Niculescu, V.C.; Soare, A.; Ion-Ebrasu, D.; Vagner, I.; Dunca, E.C.; Șandru, C.; et al. Thermochemical Processing of Agricultural Waste into Biochar with Potential Application for Coal Mining Degraded Soils. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 105497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.W.C.; Ogbonnaya, U.O. Biochar Porosity: A Nature-Based Dependent Parameter to Deliver Microorganisms to Soils for Land Restoration. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 28, 46894–46909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharyya, P.N.; Sandilya, S.P.; Sarma, B.; Pandey, A.K.; Dutta, J.; Mahanta, K.; Lesueur, D.; Nath, B.C.; Borah, D.; Borgohain, D.J. Biochar as Soil Amendment in Climate-Smart Agriculture: Opportunities, Future Prospects, and Challenges. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 135–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chvojka, J. Biorestorer: Synthetic Succession for Soil Restoration in Arid and Degraded Regions. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Zheng, X.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y.; Tang, H.; Kang, F.; Yang, Q.H.; Luo, J. Biomass Organs Control the Porosity of Their Pyrolyzed Carbon. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1604687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrafioti, E.; Kalderis, D.; Diamadopoulos, E. Ca and Fe Modified Biochars as Adsorbents of Arsenic and Chromium in Aqueous Solutions. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 146, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayoumu, M.; Wang, H.; Duan, G. Interactions between Microbial Extracellular Polymeric Substances and Biochar, and Their Potential Applications: A Review. Biochar 2025, 7, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotrba, P.; Dolečková, L.; de Lorenzo, V.; Ruml, T. Enhanced Bioaccumulation of Heavy Metal Ions by Bacterial Cells Due to Surface Display of Short Metal Binding Peptides. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 1092–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, A.; Kassem, S.; Reis, R.L.; Ulijn, R.V.; Pires, R.A.; Pashkuleva, I. Carbohydrate Amphiphiles for Supramolecular Biomaterials: Design, Self-Assembly, and Applications. Chem 2021, 7, 2943–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, B.-J.; Su, D.-Y.; Li, S.-X.; Zhang, M.; Qi, D.; Lai, F.; Tan, X.; Yang, Y. Advances in Weak-Bonded Assembly as Materials in Catalysis and Friction Applications. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, B.; Chen, M.; Crawford, R.J.; Ivanova, E.P. Bacterial Extracellular Polysaccharides Involved in Biofilm Formation. Molecules 2009, 14, 2535–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhong, M.; Wang, S. A Meta-Analysis on the Response of Microbial Biomass, Dissolved Organic Matter, Respiration, and N Mineralization in Mineral Soil to Fire in Forest Ecosystems. For. Ecol. Manag. 2012, 271, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajema, L. Effects of Biochar Application on Beneficial Soil Organism Review. Int. J. Res. Stud. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2018, 5, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kerner, P.; Struhs, E.; Mirkouei, A.; Aho, K.; Lohse, K.A.; Dungan, R.S.; You, Y. Microbial Responses to Biochar Soil Amendment and Influential Factors: A Three-Level Meta-Analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 19838–19848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, B.; Lu, H.; Chi, Z.; Pan, G.; Li, L.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, X.; et al. Biochar Soil Amendment Increased Bacterial but Decreased Fungal Gene Abundance with Shifts in Community Structure in a Slightly Acid Rice Paddy from Southwest China. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2013, 71, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Yan, L.; Tong, K.; Yu, H.; Lu, M.; Wang, L.; Niu, Y. The Potential and Prospects of Modified Biochar for Comprehensive Management of Salt-Affected Soils and Plants: A Critical Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisht, N.; Singh, T.; Ansari, M.M.; Bhowmick, S.; Rai, G.; Chauhan, P.S. Synergistic Eco-Physiological Response of Biochar and Paenibacillus Lentimorbus Application on Chickpea Growth and Soil under Drought Stress. J. Clean Prod. 2024, 438, 140822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Ding, Z.; Ali, E.F.; Kheir, A.M.S.; Eissa, M.A.; Ibrahim, O.H.M. Biochar and Compost Enhance Soil Quality and Growth of Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) under Saline Conditions. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, E.; Ekinci, M.; Turan, M. Impact of Biochar in Mitigating the Negative Effect of Drought Stress on Cabbage Seedlings. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2021, 21, 2297–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Raihan, M.R.H.; Khojah, E.; Samra, B.N.; Fujita, M.; Nahar, K. Biochar and Chitosan Regulate Antioxidant Defense and Methylglyoxal Detoxification Systems and Enhance Salt Tolerance in Jute (Corchorus olitorius l.). Antioxidants 2021, 10, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.A.F.; da Silva, B.R.S.; Nobre, J.R.C.; Batista, B.L.; da Silva Lobato, A.K. Biochar Mitigates the Harmful Effects of Drought in Soybean Through Changes in Leaf Development, Stomatal Regulation, and Gas Exchange. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 1940–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabborova, D.; Wirth, S.; Kannepalli, A.; Narimanov, A.; Desouky, S.; Davranov, K.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Enshasy, H.E.; Malek, R.A.; Syed, A.; et al. Co-Inoculation of Rhizobacteria and Biochar Application Improves Growth and Nutrientsin Soybean and Enriches Soil Nutrients and Enzymes. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Ahmad, M.; Zahid Mumtaz, M.; Nazli, F.; Aslam Farooqi, M.; Khalid, I.; Iqbal, Z.; Arshad, H. Impact of Integrated Use of Enriched Compost, Biochar, Humic Acid and Alcaligenes sp. AZ9 on Maize Productivity and Soil Biological Attributes in Natural Field Conditions. Ital. J. Agron. 2019, 14, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, B.; Gupta, S.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Kumar, R. A Comprehensive Review on Biochar against Plant Pathogens: Current State-of-the-Art and Future Research Perspectives. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Anshu; Noureldeen, A.; Darwish, H. Rhizosphere Mediated Growth Enhancement Using Phosphate Solubilizing Rhizobacteria and Their Tri-Calcium Phosphate Solubilization Activity under Pot Culture Assays in Rice (Oryza sativa). Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 3692–3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahir, Z.A.; Zafar-ul-Hye, M.; Sajjad, S.; Naveed, M. Comparative Effectiveness of Pseudomonas and Serratia sp. Containing ACC-Deaminase for Coinoculation with Rhizobium Leguminosarum to Improve Growth, Nodulation, and Yield of Lentil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2011, 47, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.Y.; Van Zwieten, L.; Meszaros, I.; Downie, A.; Joseph, S. Using Poultry Litter Biochars as Soil Amendments. Aust. J. Soil Res. 2008, 46, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matile, P.; Schellenberg, M.; Vicentini, F. Localization of Chlorophyllase in the Chloroplast Envelope. Planta 1997, 201, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, T.; Bibi, F.; Fatima, H.; Munir, F.; Gul, A.; Haider, G.; Jahanzaib, M.; Amir, R. Biochar and PGPR: A Winning Combination for Peanut Growth and Nodulation under Dry Spell. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 7680–7695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalay, G.; Ullah, A.; Iqbal, N.; Raza, A.; Asghar, M.A.; Ullah, S. The Alleviation of Drought-Induced Damage to Growth and Physio-Biochemical Parameters of Brassica napus L. Genotypes Using an Integrated Approach of Biochar Amendment and PGPR Application. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 3457–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, F.; Rafeeq, R.; Majeed, S.; Ismail, M.S.; Ahsan, M.; Ahmad, K.S.; Akram, A.; Haider, G. Biochar Amendment in Combination with Endophytic Bacteria Stimulates Photosynthetic Activity and Antioxidant Enzymes to Improve Soybean Yield Under Drought Stress. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 746–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, M.; Hajinia, S.; Jafarian, N.; Karamian, M.; Mosa, Z.; Asgharzadeh, S.; Rezaei, N.; Guidi, L.; Valkó, O.; Prévosto, B. Synergistic Use of Biochar and the Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria in Mitigating Drought Stress on Oak (Quercus brantii Lindl.) Seedlings. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 531, 120793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul-Lalay; Ullah, S.; Shah, S.; Jamal, A.; Saeed, M.F.; Mihoub, A.; Zia, A.; Ahmed, I.; Seleiman, M.F.; Mancinelli, R.; et al. Combined Effect of Biochar and Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizbacteria on Physiological Responses of Canola (Brassica napus L.) Subjected to Drought Stress. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 43, 1814–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbuganesan, V.; Vishnupradeep, R.; Bruno, L.B.; Sharmila, K.; Freitas, H.; Rajkumar, M. Combined Application of Biochar and Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria Improves Heavy Metal and Drought Stress Tolerance in Zea mays. Plants 2024, 13, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, F.; Khan, I.U.; Rutherford, S.; Dai, Z.C.; Li, G.; Du, D.L. Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria and Biochar Production from Parthenium Hysterophorus Enhance Seed Germination and Productivity in Barley under Drought Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1175097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noureen, S.; Iqbal, A.; Muqeet, H.A. Potential of Drought Tolerant Rhizobacteria Amended with Biochar on Growth Promotion in Wheat. Plants 2024, 13, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadeem, S.M.; Imran, M.; Naveed, M.; Khan, M.Y.; Ahmad, M.; Zahir, Z.A.; Crowley, D.E. Synergistic Use of Biochar, Compost and Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria for Enhancing Cucumber Growth under Water Deficit Conditions. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 5139–5145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo-Barreiro, A.; Mazuecos-Aguilera, I.; Anta-Fernández, F.; Cara-Jiménez, J.; González-Andrés, F. Enhancing Drought Resistance in Olive Trees: Understanding the Synergistic Effects of the Combination of PGPR and Biochar. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 44, 4383–4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafees, M.; Ullah, S.; Ahmed, I. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria and Biochar as Bioeffectors and Bioalleviators of Drought Stress in Faba Bean (Vicia faba L.). Folia Microbiol. 2024, 69, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, T.; Qureshi, H.; Gull, S.; Siddiqi, E.H.; Chaudhary, T.; Ali, H.M. Enhancing Zea mays Growth and Drought Resilience by Synergistic Application of Rhizobacteria-Loaded Biochar (RBC) and Externally Applied Gibberellic Acid (GA). Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 33, 103517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, A.; Rehman, M.; Naeem, Z.; Sajid, M.; Zubair, M.; Bibi, F.; Alrefaei, A.F.; Almutairi, M.H.; Zaman, W.; Naseem, M.T.; et al. Penicillium Citrinum-Infused Biochar and Externally Applied Auxin Enhances Drought Tolerance and Growth of Solanum lycopersicum L. by Modulating Physiological, Biochemical and Antioxidant Properties. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqar, A.; Bano, A.; Ajmal, M. Effects of PGPR Bioinoculants, Hydrogel and Biochar on Growth and Physiology of Soybean under Drought Stress. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2022, 53, 826–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, N.; Ditta, A.; Khalid, A.; Mehmood, S.; Rizwan, M.S.; Ashraf, M.; Mubeen, F.; Imtiaz, M.; Iqbal, M.M. Integrated Effect of Algal Biochar and Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria on Physiology and Growth of Maize Under Deficit Irrigations. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 20, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Q.; Zhao, L.; Guan, L.; Chen, P.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Du, Y.; Xie, Y. The Synergistic Interaction Effect between Biochar and Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria on Beneficial Microbial Communities in Soil. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1501400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zia, R.; Nawaz, M.S.; Siddique, M.J.; Hakim, S.; Imran, A. Plant Survival under Drought Stress: Implications, Adaptive Responses, and Integrated Rhizosphere Management Strategy for Stress Mitigation. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 242, 126626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Shahzad, R.; Hamayun, M.; Asaf, S.; Khan, A.L.; Kang, S.M.; Yun, S.; Kim, K.M.; Lee, I.J. Biochar Amendment Changes Jasmonic Acid Levels in Two Rice Varieties and Alters Their Resistance to Herbivory. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Srivastava, S. Prescience of Endogenous Regulation in Arabidopsis Thaliana by Pseudomonas Putida MTCC 5279 under Phosphate Starved Salinity Stress Condition. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, C.M.J.; Zamioudis, C.; Berendsen, R.L.; Weller, D.M.; Van Wees, S.C.M.; Bakker, P.A.H.M. Induced Systemic Resistance by Beneficial Microbes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2014, 52, 347–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glick, B.R. Bacteria with ACC Deaminase Can Promote Plant Growth and Help to Feed the World. Microbiol. Res. 2014, 169, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, S.; Caldara, M.; Gullì, M.; Bevivino, A.; Maestri, E.; Marmiroli, N. A Metagenomic and Gene Expression Analysis in Wheat (T. durum) and Maize (Z. mays) Biofertilized with PGPM and Biochar. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mushtaq, T.; Bano, A.; Ullah, A. Effects of Rhizospheric Microbes, Growth Regulators, and Biochar in Modulating Antioxidant Machinery of Plants Under Stress. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 44, 1846–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PGPR | Biochar Feedstock and Rate | Plant | Results for Drought-Stressed Plants | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biozote-Max, a PGPR based biofertilizer developed in Pakistan | Cotton (Gossypium sp.) straw 1% and 2% w/w and soil | Peanut (Arachis hypogea) | 2% biochar + PGPR reduced leaf superoxide dismutase (SOD) by 27% in a pot experiment | [104] |

| Staphylococcus sp. | Mulburry (Morus alba) wood 25% v/v | Canola (Brassica napus) | Biochar + PGPR increased nutrient uptake, leaf RWC, sugars, proteins, flavonoids, phenolic compounds, and enzymes (peroxidase (POD), SOD, glutathione reductase (GR), and dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR)) in drought-stressed plants in a pot experiment. | [105] |

| Bacillus paramycoides B. thuringiensis B. tropicus | Dalbergia sissoo wood 1% w/w and soil | Wheat (Triticum aestivum) | Biochar + PGPRs significantly increased crop yield (100-grain weight, grain yield), and soil quality (increased available P and microbial biomass) in drought-stressed plants in a pot experiment. | [63] |

| Paraburkholderia phytofirmans Bacillus sp. | Cotton stem 1% w/w and soil | Soybean (Glycine max) | Biochar + P. phytofirmans increased photosynthesis and antioxidant enzymatic activities, and improved grain yield in drought-stressed plants in a pot experiment. | [106] |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | Mistletoe (Loranthus europaeus) 10–30 g kg−1 soil | Oak (Quercus brantii) | Lower additions of Biochar + PGPR enhanced shoot growth of drought-stressed seedlings in a pot experiment. | [107] |

| Bacillus amyloliquefaciens | Timber-waste 15–30 mg kg−1 soil | Wheat | Biochar + PGPR increased growth and yield: grain yield (36%), 100-grain weight (59%), straw yield (50%); and chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, grain N and P by 114%, 123%, 58%, and 18%, respectively, in a plot experiment. | [10] |

| Pseudomonas sp. | Mulberry wood | Canola | Biochar + PGPR increased growth traits (emergence energy, leaf area), water content metrics (RWC, moisture content), nutrient levels (N, P, K, Mg, Ca); and regulated stress by reducing osmolytes (glycine, betaine, sugar) and boosting the antioxidant system (POD, SOD, GR enzymes, phenolics, flavonoids), in a plot experiment. | [108] |

| Bacillus pseudomycoides ARN7 | Peanut shell 5% w/w | Maize (Zea mays) | Biochar + PGPR helped mitigate combined heavy metal (Ni, Zn) and drought stress. They significantly improved plant growth, total chlorophyll, proteins, and relative water contents. They enhanced the antioxidant enzyme system (SOD, ascorbate peroxidase (APX), and catalase (CAT)) while reducing stress markers (electrolyte leakage, MDA, proline) in a pot experiment. | [109] |

| Serratia odorifera | Santa-Maria feverfew (Parthenium hysterophorus) 2.5% w/w | Barley (Hordeum vulgare) | Biochar + PGPR increased shoot length (37%), fresh biomass (52%), dry biomass (62%), seed germination (40%), chlorophyll a (28%) and b (35%), antioxidant enzyme activity (POD, CAT, SOD), and improved soil N, K, P, and EL by 85%, 33%, 52%, and 58%, respectively, in a plot experiment. | [110] |

| Bacillus subtilis B. tequilensis | Wheat straw, wood chips, or rice husk 1% w/w | Wheat | Biochar + PGPR increased root length (up to 70%) and shoot length (up to 82%), grains per spike (137–182%). total chlorophyll (477%) and carotenoid (423%). Key physiological indicators (membrane stability, relative water content, proline, sugar) were significantly enhanced in a pot experiment. | [111] |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | Pine wood biochar 2% w/w | Cucumber (Cucumis sativus) | Biochar + PGPR promoted shoot length (88%), shoot biomass (77%), root length (89%), and root biomass (74%) in a plot experiment. | [112] |

| Bacillus siamensis |

Olive prunings

3% w/w |

Olive

(Olea europaea) | Biochar + PGPR increased shoot biomass under both well-watered and water-stressed conditions. They reduced stress indicators ABA, H2O2, MDA) and downregulated key stress-related genes (dehydrins, aquaporins), indicating improved water status and stress tolerance in a pot experiment. | [113] |

| Cellulomonas pakistanensis NCCP11 Sphingobacterium pakistanensis NCCP246 | Mulberry wood residue 5% w/w | Faba bean (Vicia faba) | Biochar + PGPR boosted proline (77%), glycine betaine (107%), soluble sugar (83%), and total protein (89%); enhanced antioxidant enzymes (e.g., peroxidase by 81%) and reduced stress markers MDA (54%) and H2O2 (47%); and increased phenolic compounds and flavonoids by over 50% in a pot experiment | [114] |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | Maize cob 0.75% w/w and soil | Maize | Biochar + PGPR + Gibberellic Acid (GA3) increased plant dry/fresh weight, shoot/root length, protein and chlorophyll a, b, contents, in a pot experiment. | [115] |

| Paenibacillus lentimorbus B-30488 | Maize stalk 5% w/w | Chickpea (Cicer arietinum) | Biochar + PGPR improved soil physical and chemical properties, and soil microbial diversity); increased chickpea growth, improved root architecture, modulated key phytohormones (Indole acetic acid (IAA), cytokinin (CK), jasmonic acid (JA), and salicylic acid (SA)) and upregulated the expression of stress-related genes (glutathione S-transferase (GST), APX, CAT and ACC oxidase (ACO)) to maintain cellular homeostasis in a pot experiment. | [92] |

| Penicillium citrinum | Grass 3.0% w/w | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) | PGPR-loaded biochar and foliar IAA increased root length, shoot height, plant biomass chlorophyll, proline, and antioxidant enzymes (SOD, peroxidase, CAT), and reduced the stress markers H2O2 and MDA in drought-stressed plants in a pot experiment. | [116] |

| Planomicrobium chinense Pseudomonas putida | Plant leaves 5 g kg−1 | Soybean | Biochar + PGPR improved plant osmoregulant status and soil nutrient retention in a pot experiment. | [117] |

| Serratia odorifera | Algae 4% w/w | Maize | Biochar + PGPR significantly enhanced root biomass and length under severe drought (50% field capacity) in a pot experiment, demonstrating a several-fold increase compared to the non-amended control. The co-application also improved net photosynthetic rate, plant nutrient content (N, P, K), and key soil fertility parameters. | [118] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Parastesh, F.; Asgari Lajayer, B.; Dell, B. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria and Biochar as Drought Defense Tools: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanisms and Future Directions. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121040

Parastesh F, Asgari Lajayer B, Dell B. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria and Biochar as Drought Defense Tools: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanisms and Future Directions. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2025; 47(12):1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121040

Chicago/Turabian StyleParastesh, Faezeh, Behnam Asgari Lajayer, and Bernard Dell. 2025. "Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria and Biochar as Drought Defense Tools: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanisms and Future Directions" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 47, no. 12: 1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121040

APA StyleParastesh, F., Asgari Lajayer, B., & Dell, B. (2025). Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria and Biochar as Drought Defense Tools: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanisms and Future Directions. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 47(12), 1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121040