Structural Analysis of the Putative Succinyl-Diaminopimelic Acid Desuccinylase DapE from Campylobacter jejuni: Captopril-Mediated Structural Stabilization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Generation of the cjDapE Protein Expression Plasmid

2.2. cjDapE Expression and Purification

2.3. cjDapE Crystallization and X-Ray Diffraction

2.4. cjDapE Structure Determination

2.5. Gel-Filtration Chromatography of cjDapE

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Overall Structure of cjDapE in Complex with Zn2+ Ions

3.2. cjDapEZn Dimerization

3.3. Interaction of cjDapE with Captopril and Its Contribution to Structural Stabilization

3.4. Open, Inactive Conformation of the Captopril-Bound cjDapE Structure

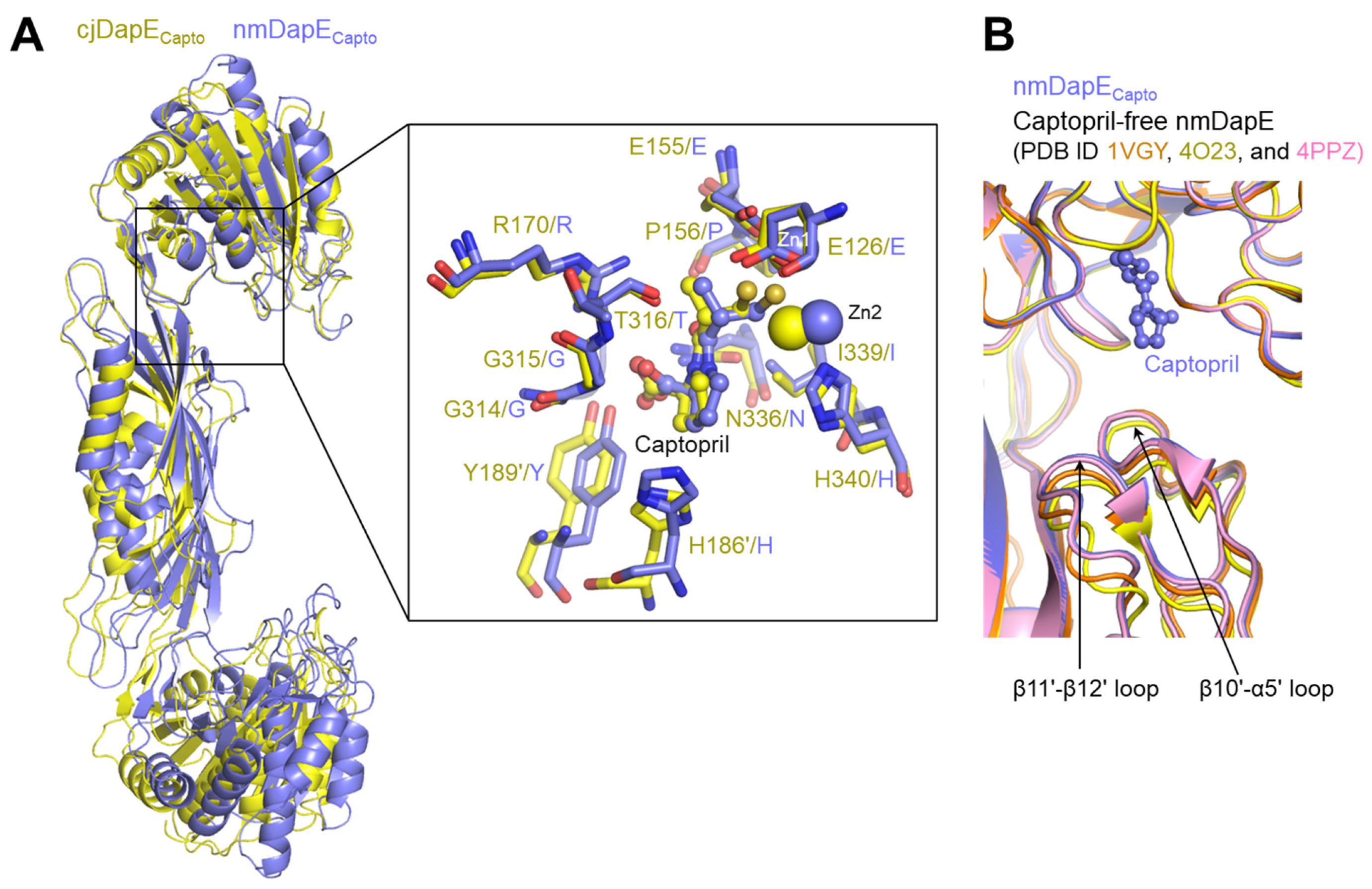

3.5. Similar but Distinct Modes of Captopril Binding Between cjDapE and nmDapE

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| abDapE | Acinetobacter baumannii DapE |

| cjDapE | Campylobacter jejuni DapE |

| cjDapECapto | Campylobacter jejuni DapE in complex with Zn2+ and captopril |

| cjDapEZn | Zn2+-bound Campylobacter jejuni DapE |

| DAP | L,L-diaminopimelic acid |

| efDapE | Enterococcus faecium DapE |

| His6 | hexa-histidine |

| hiDapE | Haemophilus influenzae DapE |

| hiDapEProduct | product-bound Haemophilus influenzae DapE |

| mDAP | meso-diaminopimelic acid |

| nmDapE | Neisseria meningitidis DapE |

| nmDapECapto | Neisseria meningitidis DapE-captopril complex |

| PAL | Pohang Accelerator Laboratory |

| SDAP | N-succinyl-L,L-diaminopimelic acid |

References

- Lin, Y.K.; Myhrman, R.; Schrag, M.L.; Gelb, M.H. Bacterial N-succinyl-L-diaminopimelic acid desuccinylase. Purification, partial characterization, and substrate specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 1622–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usha, V.; Dover, L.G.; Roper, D.I.; Futterer, K.; Besra, G.S. Structure of the diaminopimelate epimerase DapF from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2009, 65, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokulan, K.; Rupp, B.; Pavelka, M.S., Jr.; Jacobs, W.R., Jr.; Sacchettini, J.C. Crystal structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis diaminopimelate decarboxylase, an essential enzyme in bacterial lysine biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 18588–18596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmer, W.; Blanot, D.; de Pedro, M.A. Peptidoglycan structure and architecture. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 32, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karita, M.; Etterbeek, M.L.; Forsyth, M.H.; Tummuru, M.K.; Blaser, M.J. Characterization of Helicobacter pylori dapE and construction of a conditionally lethal dapE mutant. Infect. Immun. 1997, 65, 4158–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavelka, M.S., Jr.; Jacobs, W.R., Jr. Biosynthesis of diaminopimelate, the precursor of lysine and a component of peptidoglycan, is an essential function of Mycobacterium smegmatis. J. Bacteriol. 1996, 178, 6496–6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starus, A.; Nocek, B.; Bennett, B.; Larrabee, J.A.; Shaw, D.L.; Sae-Lee, W.; Russo, M.T.; Gillner, D.M.; Makowska-Grzyska, M.; Joachimiak, A.; et al. Inhibition of the dapE-Encoded N-Succinyl-L,L-diaminopimelic Acid Desuccinylase from Neisseria meningitidis by L-Captopril. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 4834–4844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, E.H.; Minasov, G.; Konczak, K.; Shuvalova, L.; Brunzelle, J.S.; Shukla, S.; Beulke, M.; Thabthimthong, T.; Olsen, K.W.; Inniss, N.L.; et al. Biochemical and Structural Analysis of the Bacterial Enzyme Succinyl-Diaminopimelate Desuccinylase (DapE) from Acinetobacter baumannii. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 3905–3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nocek, B.P.; Gillner, D.M.; Fan, Y.; Holz, R.C.; Joachimiak, A. Structural basis for catalysis by the mono- and dimetalated forms of the dapE-encoded N-succinyl-L,L-diaminopimelic acid desuccinylase. J. Mol. Biol. 2010, 397, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocek, B.; Reidl, C.; Starus, A.; Heath, T.; Bienvenue, D.; Osipiuk, J.; Jedrzejczak, R.; Joachimiak, A.; Becker, D.P.; Holz, R.C. Structural Evidence of a Major Conformational Change Triggered by Substrate Binding in DapE Enzymes: Impact on the Catalytic Mechanism. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badger, J.; Sauder, J.M.; Adams, J.M.; Antonysamy, S.; Bain, K.; Bergseid, M.G.; Buchanan, S.G.; Buchanan, M.D.; Batiyenko, Y.; Christopher, J.A.; et al. Structural analysis of a set of proteins resulting from a bacterial genomics project. Proteins 2005, 60, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrazas-Lopez, M.; Gonzalez-Segura, L.; Diaz-Vilchis, A.; Aguirre-Mendez, K.A.; Lobo-Galo, N.; Martinez-Martinez, A.; Diaz-Sanchez, A.G. The three-dimensional structure of DapE from Enterococcus faecium reveals new insights into DapE/ArgE subfamily ligand specificity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 270, 132281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spellberg, B.; Powers, J.H.; Brass, E.P.; Miller, L.G.; Edwards, J.E., Jr. Trends in antimicrobial drug development: Implications for the future. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2004, 38, 1279–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillner, D.M.; Becker, D.P.; Holz, R.C. Lysine biosynthesis in bacteria: A metallodesuccinylase as a potential antimicrobial target. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. JBIC A Publ. Soc. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 18, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillner, D.; Armoush, N.; Holz, R.C.; Becker, D.P. Inhibitors of bacterial N-succinyl-L,L-diaminopimelic acid desuccinylase (DapE) and demonstration of in vitro antimicrobial activity. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 6350–6352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidt, D.G.; Bravo, E.L.; Fouad, F.M. Drug therapy. Captopril. N. Engl. J. Med. 1982, 306, 214–219. [Google Scholar]

- Altekruse, S.F.; Stern, N.J.; Fields, P.I.; Swerdlow, D.L. Campylobacter jejuni-an emerging foodborne pathogen. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 1999, 5, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaakoush, N.O.; Castano-Rodriguez, N.; Mitchell, H.M.; Man, S.M. Global Epidemiology of Campylobacter Infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 687–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, Y.; Rojas, M.; Pacheco, Y.; Acosta-Ampudia, Y.; Ramirez-Santana, C.; Monsalve, D.M.; Gershwin, M.E.; Anaya, J.M. Guillain-Barre syndrome, transverse myelitis and infectious diseases. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2018, 15, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, L.B.; Johnson, E.; Vailes, R.; Silbergeld, E. Fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter isolates from conventional and antibiotic-free chicken products. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Shen, J. Antimicrobial Resistance in Campylobacter spp. Microbiol. Spectr. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Song, W.S.; Ki, D.U.; Cho, H.Y.; Kwon, O.H.; Cho, H.; Yoon, S.I. Structural basis of transcriptional regulation by UrtR in response to uric acid. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 13192–13205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otwinowski, Z.; Minor, W. Processing x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzym. 1997, 276, 307–326. [Google Scholar]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Zidek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, A.J.; Grosse-Kunstleve, R.W.; Adams, P.D.; Winn, M.D.; Storoni, L.C.; Read, R.J. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007, 40, 658–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emsley, P.; Cowtan, K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004, 60, 2126–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, P.D.; Afonine, P.V.; Bunkoczi, G.; Chen, V.B.; Davis, I.W.; Echols, N.; Headd, J.J.; Hung, L.W.; Kapral, G.J.; Grosse-Kunstleve, R.W.; et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010, 66, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, L. DALI and the persistence of protein shape. Protein Sci. A Publ. Protein Soc. 2020, 29, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahn, S.Y.; You, Y.-B.; Oh, H.B.; Park, M.-A.; Yoon, S.-i. Structural Analysis of the Putative Succinyl-Diaminopimelic Acid Desuccinylase DapE from Campylobacter jejuni: Captopril-Mediated Structural Stabilization. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121035

Ahn SY, You Y-B, Oh HB, Park M-A, Yoon S-i. Structural Analysis of the Putative Succinyl-Diaminopimelic Acid Desuccinylase DapE from Campylobacter jejuni: Captopril-Mediated Structural Stabilization. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2025; 47(12):1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121035

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhn, Si Yeon, Young-Bong You, Han Byeol Oh, Min-Ah Park, and Sung-il Yoon. 2025. "Structural Analysis of the Putative Succinyl-Diaminopimelic Acid Desuccinylase DapE from Campylobacter jejuni: Captopril-Mediated Structural Stabilization" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 47, no. 12: 1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121035

APA StyleAhn, S. Y., You, Y.-B., Oh, H. B., Park, M.-A., & Yoon, S.-i. (2025). Structural Analysis of the Putative Succinyl-Diaminopimelic Acid Desuccinylase DapE from Campylobacter jejuni: Captopril-Mediated Structural Stabilization. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 47(12), 1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121035