Dual-Mode Aptamer AP1-F Achieves Molecular–Morphological Precision in Cancer Diagnostics via Membrane NCL Targeting

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and Buffer Solutions

2.2. Oligonucleotide Synthesis and Sample Preparation

2.3. Microscale Thermophoresis (MST) Experiment

2.4. Orthogonal Experiment

2.5. Selectivity Analysis of G4s on Different Cells

2.6. Competitive Combination Test

2.7. Identification and Verification of Cancer Cells in Heterogeneous Cell Populations

2.8. Laser Confocal Imaging

2.9. MTT Assay

2.10. Cell Membrane NCL Double Immunofluorescence Analysis

2.11. Immunofluorescence Staining of Pathological Tissue

3. Results

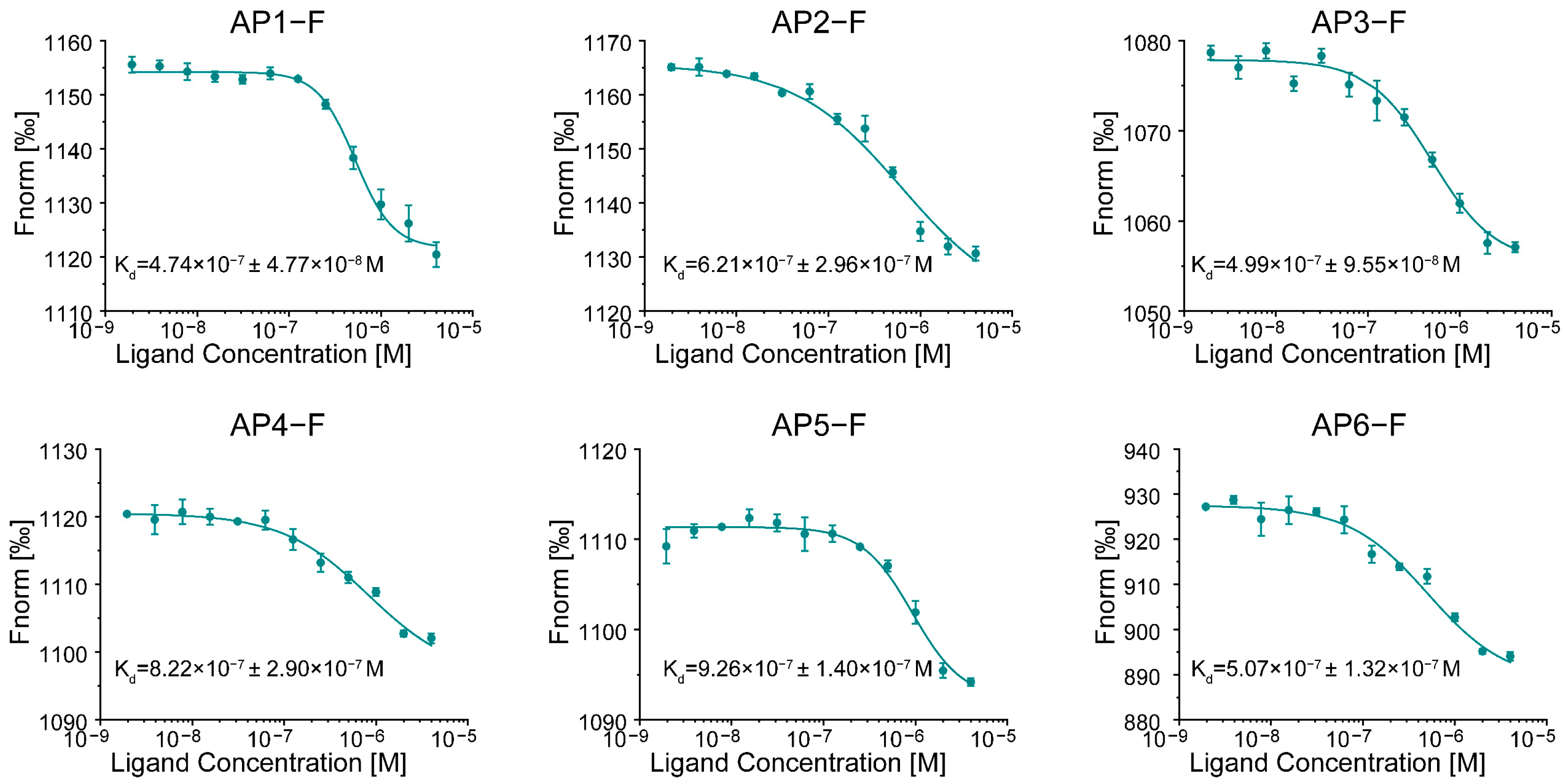

3.1. Evaluating the Binding Affinity of G4s to NCL

3.2. Orthogonal Test to Optimize Dyeing Conditions

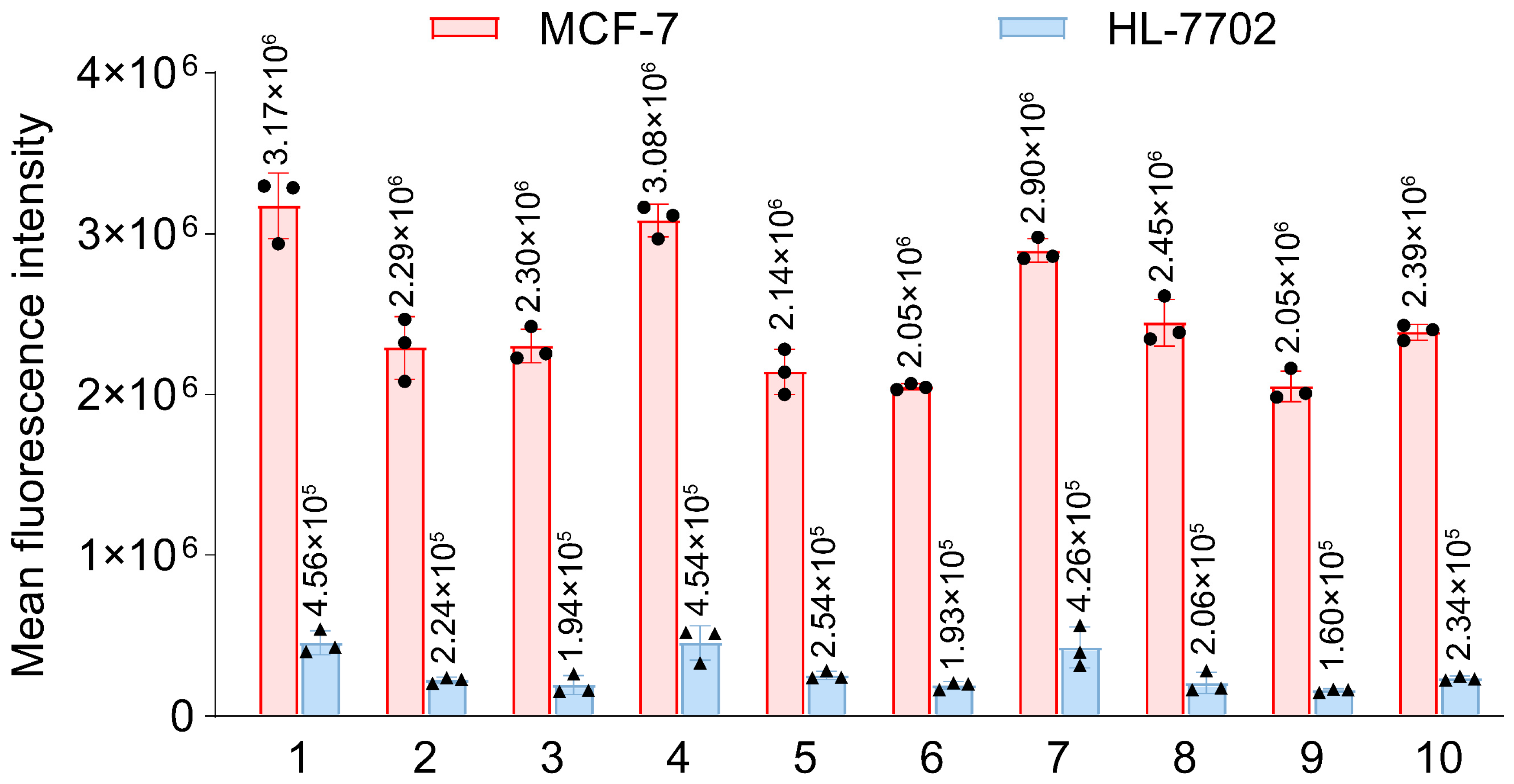

3.3. Screening for the Best G4 Aptamer

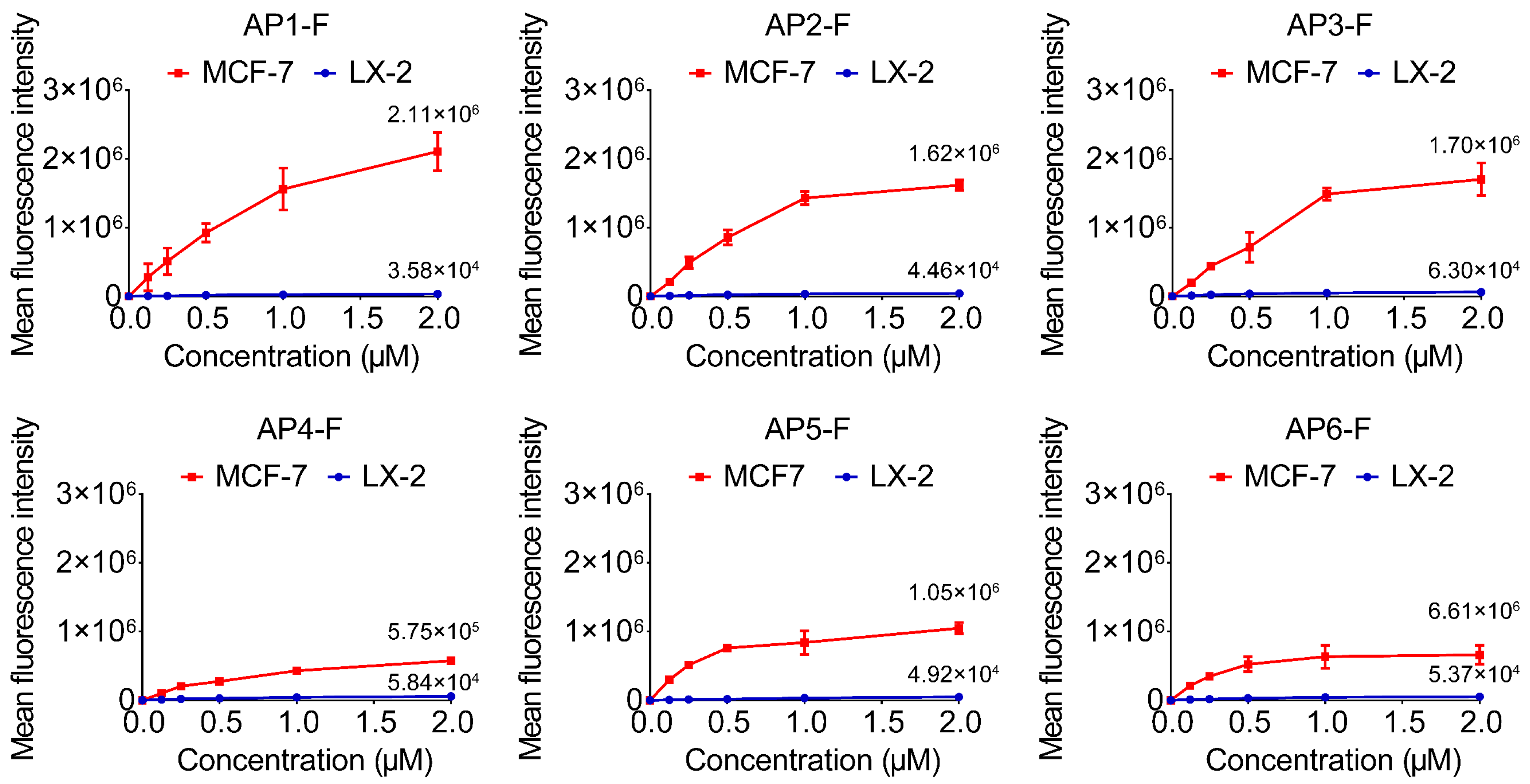

3.4. Confirm Specificity of Target Recognition

3.5. Detecting Cancer Cells in Heterogeneous Cell Populations

3.6. Verify the Ability of AP1-F to Precisely Identify Cancer Cells

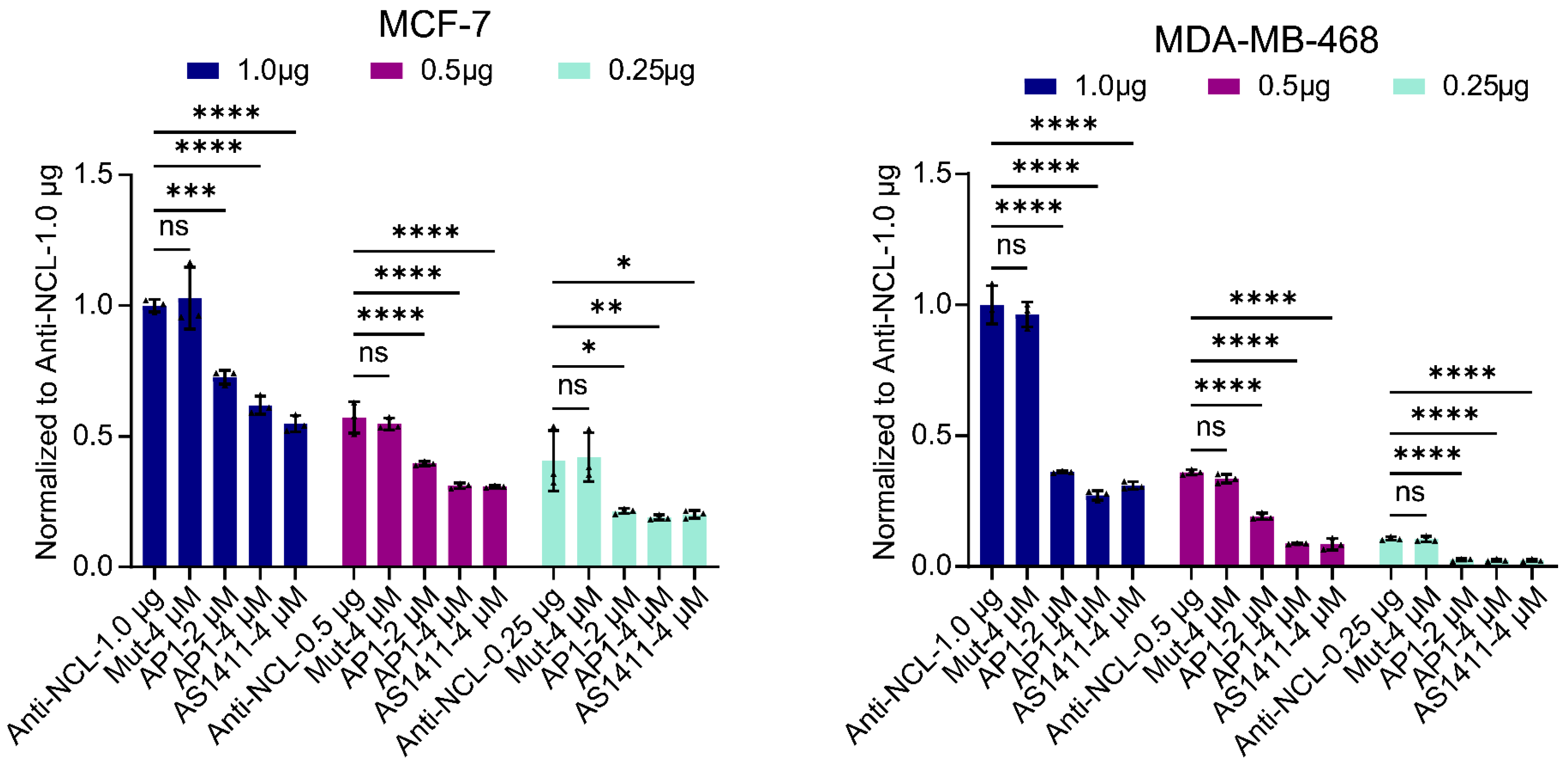

3.7. Analysis of Different NCL-Targeting Strategies and Their Mediated Cytotoxicity

3.8. Quantitative and Visual Analysis of NCL in Different Cell Membranes

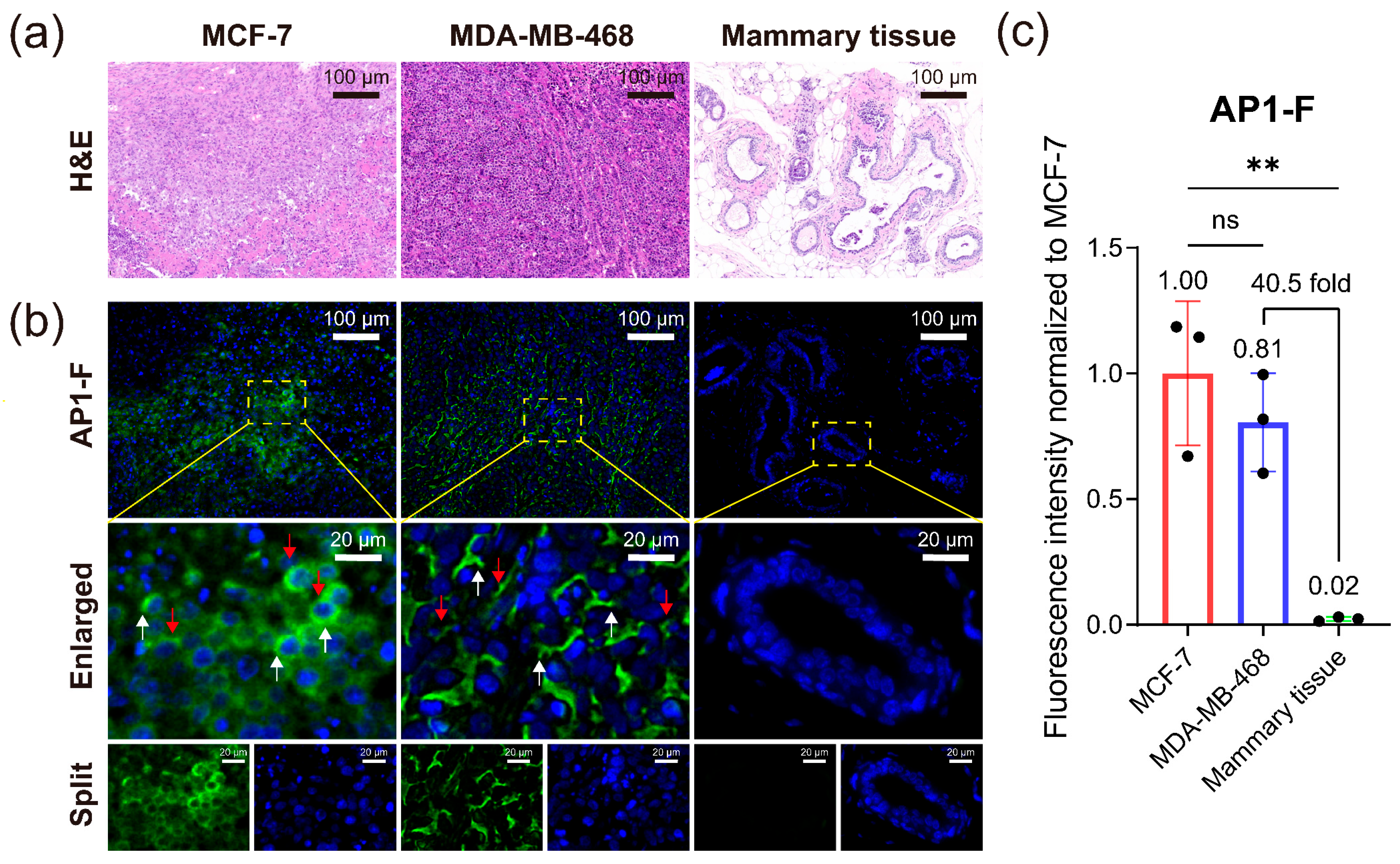

3.9. Identification and Diagnosis of Different Cancer Pathological Tissue Sections

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NCL | Nucleolin protein |

| MCF-7 | Human breast cancer cells MCF-7 |

| MDA-MB-468 | Basal-like triple-negative breast cancer cells |

| G4 | G-quadruplex |

References

- Hawkes, N. Cancer survival data emphasise importance of early diagnosis. BMJ 2019, 364, l408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Jiang, L.; Li, C.; Mao, H.; Jiang, C.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Jiang, X. Acid and Hypoxia Tandem-Activatable Deep Near-Infrared Nanoprobe for Two-Step Signal Amplification and Early Detection of Cancer. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2212231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamali, H.; Golmohammadzadeh, S.; Zare, H.; Nosrati, R.; Fereidouni, M.; Safarpour, H. The recent advancements in the early detection of cancer biomarkers by DNAzyme-assisted aptasensors. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tam, W.W.; Yu, Y.; Zhuo, Z.; Xue, Z.; Tsang, C.; Qiao, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; et al. The application of Aptamer in biomarker discovery. Biomark. Res. 2023, 11, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagami, P.; Carey, L.A. Triple negative breast cancer: Pitfalls and progress. NPJ Breast Cancer 2022, 8, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brignole, C.; Bensa, V.; Fonseca, N.A.; Del Zotto, G.; Bruno, S.; Cruz, A.F.; Malaguti, F.; Carlini, B.; Morandi, F.; Calarco, E.; et al. Cell surface Nucleolin represents a novel cellular target for neuroblastoma therapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Xu, X. Roles of nucleolin. Focus on cancer and anti-cancer therapy. Saudi Med. J. 2016, 37, 1312–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzatifar, F.; Rafiei, A.; Jeddi-Tehrani, M. Nucleolin; A tumor associated antigen as a potential lung cancer biomarker. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2022, 240, 154160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongchot, S.; Aksonnam, K.; Thuwajit, P.; Yenchitsomanus, P.T.; Thuwajit, C. Nucleolin-based targeting strategies in cancer treatment: Focus on cancer immunotherapy (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2023, 52, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Luo, J.; Xiang, F.; Liu, X.; Jiang, M.; Liao, L.; Hu, J. Nucleolin down-regulation is involved in ADP-induced cell cycle arrest in S phase and cell apoptosis in vascular endothelial cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yangngam, S.; Prasopsiri, J.; Hatthakarnkul, P.; Thongchot, S.; Thuwajit, P.; Yenchitsomanus, P.T.; Edwards, J.; Thuwajit, C. Cellular localization of nucleolin determines the prognosis in cancers: A meta-analysis. J. Mol. Med. 2022, 100, 1145–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Du, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhou, T.; Wang, F. A nucleolin-activated polyvalent aptamer nanoprobe for the detection of cancer cells. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2023, 415, 2217–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Liu, J.; Ali, M.M.; Mahmood, M.A.; Labanieh, L.; Lu, M.; Iqbal, S.M.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, W.; Wan, Y. Nucleic acid aptamers in cancer research, diagnosis and therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 1240–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.M.; Liu, H.; Kuai, H.; Peng, R.; Mo, L.; Zhang, X.B. Aptamer-integrated DNA nanostructures for biosensing, bioimaging and cancer therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 2583–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, D.; Chakraborty, S.; Pal, R.; Sharma, T.K.; Sarkar, S. Identification and Engineering of Aptamers for Theranostic Application in Human Health and Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhou, J.; Shao, Z.; Liu, J.; Song, J.; Wang, R.; Li, J.; Tan, W. Aptamers as Versatile Molecular Tools for Antibody Production Monitoring and Quality Control. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 12079–12086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Wei, J.; Zhang, L.; Hou, X.; Tan, J.; Yuan, Q.; Tan, W. Aptamer-Protein Interactions: From Regulation to Biomolecular Detection. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 12471–12506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zu, Y. Aptamers and their applications in nanomedicine. Small 2015, 11, 2352–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y.; Lin, B.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J.; Wan, S.; Yang, C.; Tan, W. Aptamer-Based Detection of Circulating Targets for Precision Medicine. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 12035–12105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Chen, X. Aptamer-based targeted therapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 134, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, E.; Riccardi, C.; Gaglione, R.; Arciello, A.; Pirota, V.; Triveri, A.; Doria, F.; Musumeci, D.; Montesarchio, D. Selective light-up of dimeric G-quadruplex forming aptamers for efficient VEGF (165) detection. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 224, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamay, G.; Koshmanova, A.; Narodov, A.; Gorbushin, A.; Voronkovskii, I.; Grek, D.; Luzan, N.; Kolovskaya, O.; Shchugoreva, I.; Artyushenko, P.; et al. Visualization of Brain Tumors with Infrared-Labeled Aptamers for Fluorescence-Guided Surgery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 24989–25004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Gao, S.; Wu, J.; Hu, X. A Fluorescent Aptasensor Based on Assembled G-Quadruplex and Thioflavin T for the Detection of Biomarker VEGF165. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 764123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, D.; Yuan, J.H.; Chen, S.B.; Tan, J.H.; Kwok, C.K. Selective targeting of parallel G-quadruplex structure using L-RNA aptamer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 11439–11452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, B.; Palumbo, M.; Sissi, C. Nucleic acid aptamers based on the G-quadruplex structure: Therapeutic and diagnostic potential. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 1248–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxo, C.; Kotkowiak, W.; Pasternak, A. G-Quadruplex-Forming Aptamers-Characteristics, Applications, and Perspectives. Molecules 2019, 24, 3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, S.; Tosoni, E.; Nadai, M.; Palumbo, M.; Richter, S.N. The cellular protein nucleolin preferentially binds long-looped G-quadruplex nucleic acids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861 Pt B, 1371–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palsson, S.A.; Dondalska, A.; Bergenstrahle, J.; Rolfes, C.; Bjork, A.; Sedano, L.; Power, U.F.; Rameix-Welti, M.A.; Lundeberg, J.; Wahren-Herlenius, M.; et al. Single-Stranded Oligonucleotide-Mediated Inhibition of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 580547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, V.; Guo, K.; Hurley, L.; Sun, D. Identification and characterization of nucleolin as a c-myc G-quadruplex-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 23622–23635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Duchambon, P.; Masson, V.; Loew, D.; Bombard, S.; Teulade-Fichou, M.P. Nucleolin Discriminates Drastically between Long-Loop and Short-Loop Quadruplexes. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 1261–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.D.; Ishizuka, T.; Zhu, X.Q.; Li, Y.; Sugiyama, H.; Xu, Y. Unusual Topological RNA Architecture with an Eight-Stranded Helical Fragment Containing A-, G-, and U-Tetrads. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 2565–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.D.; Zhong, M.Q.; Gao, Y.; Yang, Z.L.; Jia, M.H.; Hu, X.H.; Xu, Y.; Shen, X.C. A Unique G-Quadruplex Aptamer: A Novel Approach for Cancer Cell Recognition, Cell Membrane Visualization, and RSV Infection Detection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, D.; Richmond, T.; Piovan, C.; Sheetz, T.; Zanesi, N.; Troise, F.; James, C.; Wernicke, D.; Nyei, F.; Gordon, T.J.; et al. Human anti-nucleolin recombinant immunoagent for cancer therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 9418–9423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundararajan, S.; Chen, W.; Spicer, E.K.; Courtenay-Luck, N.; Fernandes, D.J. The nucleolin targeting aptamer AS1411 destabilizes Bcl-2 messenger RNA in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 2358–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Bae, C.; Kim, M.J.; Song, I.H.; Ryu, J.H.; Choi, J.H.; Lee, C.J.; Nam, J.S.; Kim, J.I. A novel nucleolin-binding peptide for Cancer Theranostics. Theranostics 2020, 10, 9153–9171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghei, Y.S.; Hosseini, M.; Dadmehr, M.; Hosseinkhani, S.; Ganjali, M.R.; Sheikhnejad, R. Visual detection of cancer cells by colorimetric aptasensor based on aggregation of gold nanoparticles induced by DNA hybridization. Anal. Chim. Acta 2016, 904, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, A.; Ranjbar, E.; Amiri, S.; Ezzatifar, F. Beyond biomarkers: Exploring the diverse potential of a novel phosphoprotein in lung cancer management. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e70077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T.; Miranda, A.; Campello, M.P.C.; Paulo, A.; Salgado, G.; Cabrita, E.J.; Cruz, C. Recognition of nucleolin through interaction with RNA G-quadruplex. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 189, 114208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleimenova, A.; Frasco, M.F.; Sales, M.G.F. An ultrasensitive paper-based SERS sensor for detection of nucleolin using silver-nanostars, plastic antibodies and natural antibodies. Talanta 2024, 279, 126543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Tang, S.; Wang, M.; Li, L.; Li, J.; Wang, D.; Mi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, X.; Yue, S. “Triple-Punch” Strategy Exosome-Mimetic Nanovesicles for Triple Negative Breast Cancer Therapy. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 5470–5482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, J.; Xu, Y.; Lou, B.; Li, D.; Wang, E. Multifunctional AS1411-functionalized fluorescent gold nanoparticles for targeted cancer cell imaging and efficient photodynamic therapy. Talanta 2014, 118, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatami, F.; Matin, M.M.; Danesh, N.M.; Bahrami, A.R.; Abnous, K.; Taghdisi, S.M. Targeted delivery system using silica nanoparticles coated with chitosan and AS1411 for combination therapy of doxorubicin and antimiR-21. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 266, 118111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.T.; O’Toole, M.G.; Casson, L.K.; Thomas, S.D.; Bardi, G.T.; Reyes-Reyes, E.M.; Ng, C.K.; Kang, K.A.; Bates, P.J. AS1411-conjugated gold nanospheres and their potential for breast cancer therapy. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 22270–22281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdian-Robati, R.; Bayat, P.; Oroojalian, F.; Zargari, M.; Ramezani, M.; Taghdisi, S.M.; Abnous, K. Therapeutic applications of AS1411 aptamer, an update review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 155, 1420–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Lu, X.; Luo, L.; Dou, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, G.; Zhao, L.; Sun, F. Targeting glutamine synthetase with AS1411-modified exosome-liposome hybrid nanoparticles for inhibition of choroidal neovascularization. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, Y.; Cai, M.; Zhou, L.; Jiang, J.; Gao, J.; Wang, H. Aptamer AS1411 utilized for super-resolution imaging of nucleolin. Talanta 2020, 217, 121037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Gao, F.; Ma, J.; Ma, H.; Dong, G.; Sheng, C. Aptamer-PROTAC Conjugates (APCs) for Tumor-Specific Targeting in Breast Cancer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 23299–23305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, Y.; Khan, I.; Dongsar, T.T.; Alsayari, A.; Wahab, S.; Sahebkar, A.; Kesharwani, P. AS1411 aptamer based nanomaterials: A novel approach for breast cancer therapy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 318, 145125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Z.; Wang, L.; Xiao, C.; Shen, X. Dual-Mode Aptamer AP1-F Achieves Molecular–Morphological Precision in Cancer Diagnostics via Membrane NCL Targeting. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 904. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47110904

Yang Z, Wang L, Xiao C, Shen X. Dual-Mode Aptamer AP1-F Achieves Molecular–Morphological Precision in Cancer Diagnostics via Membrane NCL Targeting. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2025; 47(11):904. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47110904

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Zhenglin, Lingwei Wang, Chaoda Xiao, and Xiangchun Shen. 2025. "Dual-Mode Aptamer AP1-F Achieves Molecular–Morphological Precision in Cancer Diagnostics via Membrane NCL Targeting" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 47, no. 11: 904. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47110904

APA StyleYang, Z., Wang, L., Xiao, C., & Shen, X. (2025). Dual-Mode Aptamer AP1-F Achieves Molecular–Morphological Precision in Cancer Diagnostics via Membrane NCL Targeting. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 47(11), 904. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47110904