Identification and Association of CYP2R1, CYP27B1, and GC Gene Polymorphisms with Vitamin D Deficiency in Apparently Healthy Population and in Silico Analysis of the Binding Pocket of Vitamin D3

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. DNA Isolation

2.3. Selection of Genetic Variants

2.4. Genetic Screening of Exons

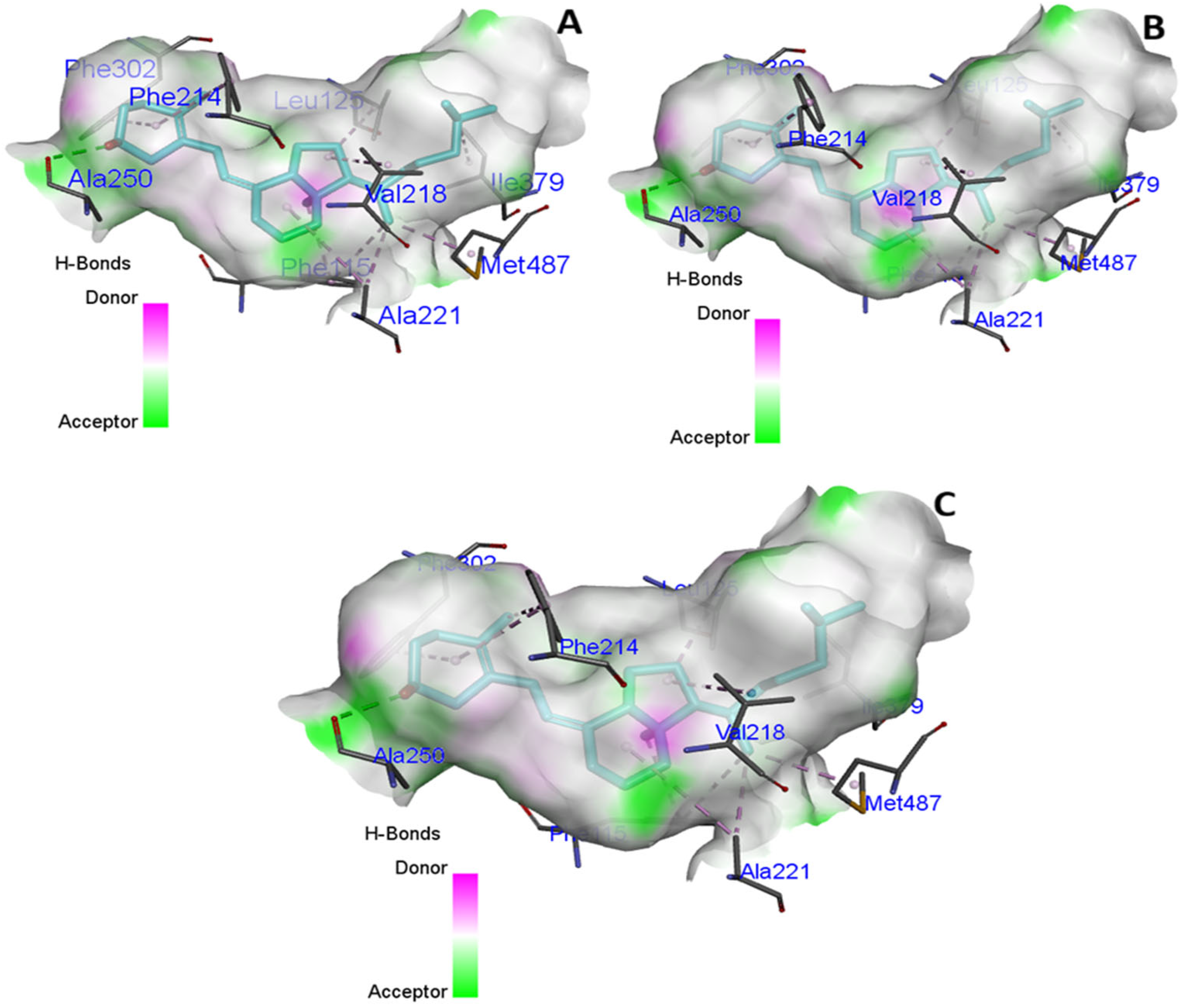

2.5. In Silico Modeling of GC and CYP2R1 Protein and Binding Pocket Analysis of Vitamin D3

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Genotyping Analysis of rs7041 (GC), rs782153744, rs200183599 (CYP2R1), rs118204011, and rs28934604 (CYP27B1 Gene)

3.2. Sanger Sequencing of Exons

3.3. In Silico Molecular Modeling and Binding Pocket Analysis of GC and CYP2R1 Proteins with Vitamin D3

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kägi, L.; Bettoni, C.; Pastor-Arroyo, E.M.; Schnitzbauer, U.; Hernando, N.; Wagner, C.A. Regulation of vitamin D metabolizing enzymes in murine renal and extrarenal tissues by dietary phosphate, FGF23, and 1, 25 (OH) 2D3. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pike, J.W.; Christakos, S. Biology and mechanisms of action of the vitamin D hormone. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. 2017, 46, 815–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, A.I.; Bhatti, A.M.; Khan, R. Assessment of Vitamin D Deficiency and its Possible Risk with Breast Cancer in Pakistan. Pak. J. Med. Health Sci. 2023, 17, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, A.A.; Memon, N.A.; Rabbani, U.; Soomro, A.K.; Jahanghir, S. Vitamin D Deficiency in the Patients of Diabetes Mellitus and Its Correlation with HbA1c. Ann. Punjab Med. Coll. 2023, 17, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughal, I.A.; Safdar, S.; Moazzam, S.; Irfan, A.; Farooqi, A.; Ismail, M. Association of CYP24A1 gene, Vitamin D deficiency and heart diseases in Pakistani patients. J. Exp. Clin. Med. 2022, 39, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatem, N.; Rohadi Rosyidi, M.S.; Tariq, S.; Wulandari, P. A Cross-Sectional Study on Vitamin D Deficiency as a Risk Factor for Depression in the Elderly. Avicenna J. Health Sci. 2024, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, Y.; Waris, N.; Fawwad, A.; Basit, A. Vitamin D deficiency and diseases: A review from Pakistan. J. Diabetol. 2021, 12, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimalawansa, S.J. Physiology of vitamin D—Focusing on disease prevention. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, A.L.; Blackbourn, D.J.; Ahmadi, K.R.; Lanham-New, S.A. Very high prevalence of 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency in 6433 UK South Asian adults: Analysis of the UK Biobank Cohort. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 125, 448–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Muzammil, S.M.; Jafri, L.; Khan, A.H. An audit of clinical laboratory data of 25 [OH] D at Aga Khan University as reflecting vitamin D deficiency in Pakistan. JPMA J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2015, 65, 1247–1250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sadat-Ali, M.; Al-Turki, H.A.; Azam, M.Q.; Al-Elq, A.H. Genetic influence on circulating vitamin D among Saudi Arabians. Saudi Med. J. 2016, 37, 996. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, S.; Liu, Y.; Ren, L. Relationship between polymorphisms in vitamin D metabolism-related genes and the risk of rickets in Han Chinese children. BMC Med. Genet. 2013, 14, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nissen, J.; Rasmussen, L.B.; Ravn-Haren, G.; Andersen, E.W.; Hansen, B.; Andersen, R.; Mejborn, H.; Madsen, K.H.; Vogel, U. Common variants in CYP2R1 and GC genes predict vitamin D concentrations in healthy Danish children and adults. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrar, Y.; Alhammadin, G.; Lee, S.-J. Genetic polymorphisms in cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in vitamin D metabolism and the vitamin D receptor: Their clinical relevance. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaid, K.; Rehman, A.; Jolliffe, D.A.; Saeed, T.; Wood, K.; Martineau, A.R. Vitamin D deficiency associates with susceptibility to tuberculosis in Pakistan, but polymorphisms in VDR, DBP and CYP2R1 do not. BMC Pulm. Med. 2016, 16, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lone, N.M.; Riaz, S.; Eusaph, A.Z.; Mein, C.A.; Wozniak, E.L.; Xenakis, T.; Wu, Z.; Younis, S.; Jolliffe, D.A.; Junaid, K. Genotype-independent association between vitamin D deficiency and polycystic ovarian syndrome in Lahore, Pakistan. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Arifa, N.; Jahan, N. Association of Glutathione-S-Transferase P1 (GSTP1) and Group-Specific Component (GC) Polymorphism with the Risk of Asthma in Pakistani Population. Pak. J. Zool. 2016, 48, 937–942. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, K.; Islam, N.; Azam, I.; Asghar, A.; Mehboobali, N.; Iqbal, M.P. Association of Vitamin D binding protein polymorphism with risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in a Pakistani urban population: A case control study. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2017, 67, 1658. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mubashir, M.; Anwar, S.; Tareen, A.K.; Mehboobali, N.; Iqbal, K.; Iqbal, M.P. Association of vitamin D deficiency and VDBP gene polymorphism with the risk of AMI in a Pakistani population. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 33, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiaz, H.; Khan, A.R.; Ehrhart, F.; Hussain, M.; Evelo, C.T.; Awan, F.R.; Coort, S.L. Investigating the role of Vitamin D and its targeted gene-pathway interactions involved in cardiometabolic health. Int. J. Health Sci. 2025, 19, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, A.A.; Unar, F.; Khan, F.A.; Karamat, S.; Khokhar, N.A.; Memon, A. Prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy in asymptomatic population. Prof. Med. J. 2020, 27, 2569–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, K.L.; Akhter, Q.S.; Rahman, M.S.; Rahman, R.; Rahman, S.; Mukta, F.Y.; Sarker, S. Genetic variations of CYP2R1 (rs10741657) in Bangladeshi adults with low serum 25 (OH) D level—A pilot study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Płudowski, P.; Kos-Kudła, B.; Walczak, M.; Fal, A.; Zozulińska-Ziółkiewicz, D.; Sieroszewski, P.; Peregud-Pogorzelski, J.; Lauterbach, R.; Targowski, T.; Lewiński, A. Guidelines for preventing and treating vitamin D deficiency: A 2023 update in Poland. Nutrients 2023, 15, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. J. Am. Col. Dent. 2014, 81, 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J.; Russell, D.W. Purification of nucleic acids by extraction with phenol: Chloroform. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2006, 2006, prot4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.H.; Jafri, L.; Siddiqui, A.; Naureen, G.; Morris, H.; Moatter, T. Polymorphisms in the GC gene for vitamin D binding protein and their association with vitamin D and bone mass in young adults. Metabolism 2019, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.; Ke, X. Primer1: Primer design web service for tetra-primer ARMS-PCR. Open Bioinform. J. 2012, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, S.C.; Austine-Orimoloye, O.; Azov, A.G.; Barba, M.; Barnes, I.; Barrera-Enriquez, V.P.; Becker, A.; Bennett, R.; Beracochea, M.; Berry, A.; et al. Ensembl 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 53, D948–D957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.M.; Studer, G.; Robin, X.; Bienert, S.; Tauriello, G.; Schwede, T. The structure assessment web server: For proteins, complexes and more. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W318–W323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chen, J.; Cheng, T.; Gindulyte, A.; He, J.; He, S.; Li, Q.; Shoemaker, B.A.; Thiessen, P.A.; Yu, B. PubChem 2025 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D1516–D1525. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bugnon, M.; Röhrig, U.F.; Goullieux, M.; Perez, M.A.S.; Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissDock 2024: Major enhancements for small-molecule docking with Attracting Cavities and AutoDock Vina. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W324–W332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Chan, H.S.; Hu, Z. Using PyMOL as a platform for computational drug design. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2017, 7, e1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, H.M.; Westbrook, J.; Feng, Z.; Gilliland, G.; Bhat, T.N.; Weissig, H.; Shindyalov, I.N.; Bourne, P.E. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, J.M.; Rödelsperger, C.; Schuelke, M.; Seelow, D. MutationTaster evaluates disease-causing potential of sequence alterations. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 575–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, N.-L.; Kumar, P.; Hu, J.; Henikoff, S.; Schneider, G.; Ng, P.C. SIFT web server: Predicting effects of amino acid substitutions on proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, W452–W457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solé, X.; Guinó, E.; Valls, J.; Iniesta, R.; Moreno, V. SNPStats: A web tool for the analysis of association studies. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 1928–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: A User-Friendly Biological Sequence Alignment Editor and Analysis Program for Windows 95/98/NT; Nucleic Acids Symposium Series; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999; pp. 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, R.A.; Larsen, L.H.; Damsgaard, C.T.; Sørensen, L.B.; Hjorth, M.F.; Andersen, R.; Tetens, I.; Krarup, H.; Ritz, C.; Astrup, A. Common genetic variants are associated with lower serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations across the year among children at northern latitudes. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 117, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.; Singh, H.; Tiwari, P.; Sood, A.; Midha, V.; Singh, G.; Thelma, B.; Senapati, S. Assessment of the contribution of VDR and VDBP/GC genes in the pathogenesis of celiac disease. J. Genet. 2024, 103, 29, Correction in J. Genet. 2025, 104, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saechua, C.; Sarachana, T.; Chonchaiya, W.; Trairatvorakul, P.; Yuwattana, W.; Poolcharoen, C.; Sangritdech, M.; Saeliw, T.; van Erp, M.L.; Sangsuthum, S. Impact of gene polymorphisms involved in the vitamin D metabolic pathway on the susceptibility to and severity of autism spectrum disorder. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshkibaf, M.H.; Mousazadeh, S.; Maleknia, M.; Takhshid, M.A. Association of vitamin D deficiency with vitamin D binding protein (DBP) and CYP2R1 polymorphisms in Iranian population. Meta Gene 2021, 27, 100824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus Brait, B.; da Silva Lima, S.P.; Aguiar, F.L.; Fernandes-Ferreira, R.; Oliveira-Brancati, C.I.F.; Ferraz, J.A.M.L.; Tenani, G.D.; de Souza Pinhel, M.A.; Assoni, L.C.P.; Nakahara, A.H. Genetic polymorphisms related to the vitamin D pathway in patients with cirrhosis with or without hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Ecancermedicalscience 2022, 16, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verboven, C.; Rabijns, A.; De Maeyer, M.; Van Baelen, H.; Bouillon, R.; De Ranter, C. A structural basis for the unique binding features of the human vitamin D-binding protein. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002, 9, 131–136, Erratum in Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2002, 9, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.X.; Zhou, G.; Zhao, M.; Sano, D.; Jasser, S.A.; Brennan, R.G.; Myers, J.N. Serine substitution of proline at codon 151 of TP53 confers gain of function activity leading to anoikis resistance and tumor progression of head and neck cancer cells. Laryngoscope 2013, 123, 1416–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciel-Cruz, E.J.; Figuera-Villanueva, L.E.; Gómez-Flores-Ramos, L.; Hernández-Peña, R.; Gallegos-Arreola, M.P. In-Silico Method for Predicting Pathogenic Missense Variants Using Online Tools: AURKA Gene as a Model. Iran. J. Biotechnol. 2024, 22, e3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casella, A.; Long, C.; Zhou, J.; Lai, M.; O’Lear, L.; Caplan, I.; Levine, M.A.; Roizen, J.D. Differential frequency of CYP2R1 variants across populations reveals pathway selection for vitamin D homeostasis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, 1302–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharazy, S.; Naseer, M.I.; Alissa, E.; Robertson, M.D.; Lanham-New, S.; Alqahtani, M.H.; Chaudhary, A.G. Association of SNPs in GC and CYP2R1 with total and directly measured free 25-hydroxyvitamin D in multi-ethnic postmenopausal women in Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 4626–4632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, F.; Yu, S.; Zhang, D.; Wang, J.; Han, H.; Sun, H.; Xue, Y.; Ba, Y.; Wang, C. Triangular relationship between CYP2R1 gene polymorphism, serum 25 (OH) D3 levels and T2DM in a Chinese rural population. Gene 2018, 678, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, H.; Sampath, P.; Kumar, V.; Veerasamy, A.; Ranganathan, U.D.; Paramasivam, S.; Bethunaickan, R. Association of CYP27B1 gene polymorphisms with pulmonary tuberculosis and vitamin D levels. Gene 2024, 927, 148679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramagopalan, S.V.; Dyment, D.A.; Cader, M.Z.; Morrison, K.M.; Disanto, G.; Morahan, J.M.; Berlanga-Taylor, A.J.; Handel, A.; De Luca, G.C.; Sadovnick, A.D. Rare variants in the CYP27B1 gene are associated with multiple sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2011, 70, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selahvarzi, H.; Kamdideh, M.; Vahabi, M.; Dezhgir, A.; Houshmand, M.; Sadeghi, S. Association of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in the VDR and CYP27B1 Genes with Risk of Developing Vitamin D3 Deficiency. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 15, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, E.T.; Van Pelt, C.; Forster, R.E.; Zaidi, W.; Hibler, E.A.; Galligan, M.A.; Haussler, M.R.; Jurutka, P.W. CYP24A1 and CYP27B1 polymorphisms modulate vitamin D metabolism in colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 2563–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munazza, M.H.Y.; Atta, J.; Syed, B.Q.; Ahmad, Z.; Khan, B.; Mehboob, N.; Bibi, A. Vitamin D Deficiency: Lesson for Pakistan, A Meta-Analysis. J. Popul. Ther. Clin. Pharmacology. 2024, 31, 456–468. Available online: https://jptcp.com/index.php/jptcp/article/view/7778/7351 (accessed on 26 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mandal, J.; Chanda, A.; Sarkar, S. Outdoor PM2.5 pollution levels and their degree of compliance with WHO air quality guidelines across 760 cities in China, India, and Pakistan. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Li, D.; Tian, Y.; Wang, P. Ambient air pollutions are associated with vitamin D status. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 6887. [Google Scholar]

- Thirunavukkarasu, R.; Chitra, A.; Asirvatham, A.; Jayalakshmi, M. Association of Vitamin D deficiency and vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms with type 1 diabetes risk: A South Indian familial study. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2024, 16, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulan, B.; Hoscan, A.; Keskin, S.; Cavus, A.; Culcu, E.; Isik, N.; List, E.; Arman, A. Vitamin D receptor polymorphisms among the Turkish population are associated with multiple sclerosis. Balk. J. Med. Genet. BJMG 2023, 25, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Wu, F.; Ni, S.; Guo, S.; Lu, L.; Zhao, X. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms are associated with the risk and features of myasthenia gravis in the Han Chinese population. Immunol. Res. 2023, 71, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medrano, R.F.V.; De Oliveira, C.A. Guidelines for the tetra-primer ARMS–PCR technique development. Mol. Biotechnol. 2014, 56, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SNPs | Genotype and Alleles | Cases (n = 300) | Controls (n = 300) |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs200183599 (CYP2R1) | AA | 300 (100%) | 300 (100%) |

| AG | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| GG | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| A | 600 (100%) | 600 (100%) | |

| G | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| rs782153744 (G > T) (CYP2R1) | GG | 228 (76%) | 289 (96%) |

| GT | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| TT | 72 (24%) | 11 (4%) | |

| G | 456 (76%) | 289 (96%) | |

| T | 144 (24%) | 11 (4%) | |

| rs782153744 (G > C) (CYP2R1) | GG | 84 (28%) | 15 (5%) |

| GC | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.3%) | |

| CC | 215 (71.6%) | 284 (94.6%) | |

| G | 169 (28.16%) | 31 (5.16%) | |

| C | 431 (71.83%) | 569 (94.83%) | |

| rs28934604 (CYP27B1) | GG | 259 (86%) | 258 (86%) |

| GA | 6 (2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| AA | 35 (11.66%) | 42 (14%) | |

| G | 524 (87%) | 516 (86%) | |

| A | 76 (13%) | 84 (14%) | |

| rs118204011 (CYP27B1) | CC | 215 (71.66%) | 203 (67.66%) |

| CT | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.6%) | |

| TT | 85 (28.33%) | 95 (31.66%) | |

| C | 430 (71.66%) | 408 (68%) | |

| T | 170 (28.33%) | 192 (32%) | |

| rs7041 (T > G) (GC) | TT | 191 (64%) | 300 (100%) |

| TG | 2 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| GG | 107 (36%) | 0 (0%) | |

| T | 384 (64%) | 600 (100%) | |

| G | 216 (36%) | 0 (0%) | |

| rs7041 (T > A) (GC) | TT | 239 (79.66%) | 300 (100%) |

| TA | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| AA | 60 (20%) | 0 (0%) | |

| T | 479 (79.83%) | 600 (100%) | |

| A | 121 (20.16%) | 0 (0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manzoor, S.; Majeed, A.; Waheed, P.; Rashid, A. Identification and Association of CYP2R1, CYP27B1, and GC Gene Polymorphisms with Vitamin D Deficiency in Apparently Healthy Population and in Silico Analysis of the Binding Pocket of Vitamin D3. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47100849

Manzoor S, Majeed A, Waheed P, Rashid A. Identification and Association of CYP2R1, CYP27B1, and GC Gene Polymorphisms with Vitamin D Deficiency in Apparently Healthy Population and in Silico Analysis of the Binding Pocket of Vitamin D3. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2025; 47(10):849. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47100849

Chicago/Turabian StyleManzoor, Saima, Asifa Majeed, Palvasha Waheed, and Amir Rashid. 2025. "Identification and Association of CYP2R1, CYP27B1, and GC Gene Polymorphisms with Vitamin D Deficiency in Apparently Healthy Population and in Silico Analysis of the Binding Pocket of Vitamin D3" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 47, no. 10: 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47100849

APA StyleManzoor, S., Majeed, A., Waheed, P., & Rashid, A. (2025). Identification and Association of CYP2R1, CYP27B1, and GC Gene Polymorphisms with Vitamin D Deficiency in Apparently Healthy Population and in Silico Analysis of the Binding Pocket of Vitamin D3. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 47(10), 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47100849