A Systematic Review on the Effect of Nutraceuticals on Antidepressant-Induced Sexual Dysfunctions: From Basic Principles to Clinical Applications

Abstract

:1. Introduction

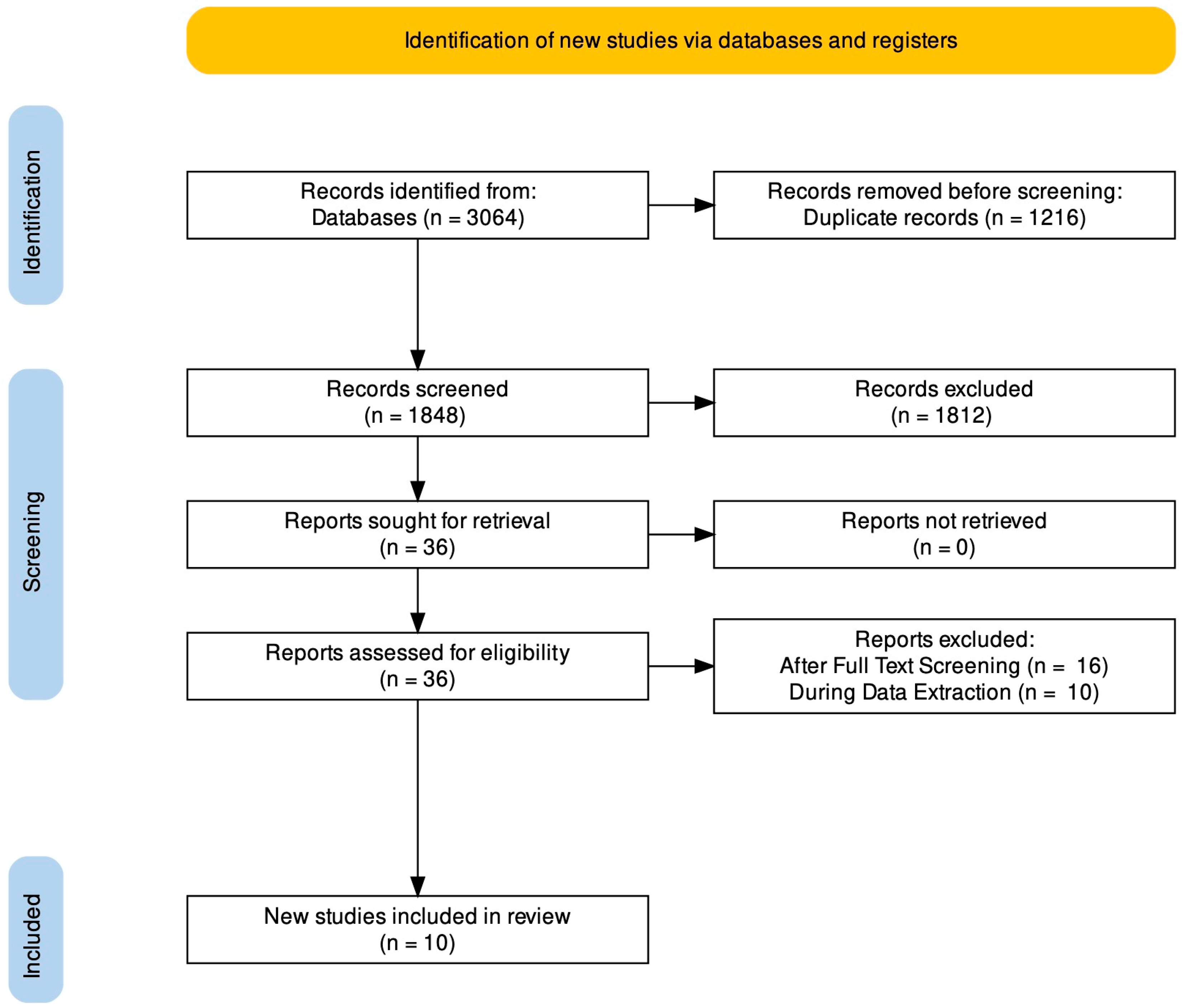

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Maca Root

3.2. SAMe

3.3. Rosa Damascena

3.4. Ginkgo Biloba

3.5. Saffron

3.6. Yohimbine

3.7. Quality of the Studies Included

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of the Evidence and Proposed Mechanisms

4.2. Conclusions

5. Study Limitations and Research Agenda

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rothmore, J. Antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction. Med. J. Aust. 2020, 212, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, J. Adverse Effects of Antidepressants Reported by a Large International Cohort: Emotional Blunting, Suicidality, and Withdrawal Effects. Curr. Drug Saf. 2018, 13, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Atmaca, M. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor-Induced Sexual Dysfunction: Current Management Perspectives. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 16, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- AlBreiki, M.; AlMaqbali, M.; AlRisi, K.; AlSinawi, H.; Al Balushi, M.; Al Zakwani, W. Prevalence of antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction among psychiatric outpatients attending a tertiary care hospital. Neurosciences 2020, 25, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, T.; Rullo, J.; Faubion, S. Antidepressant-Induced Female Sexual Dysfunction. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2016, 91, 1280–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Segraves, R.T.; Balon, R. Antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction in men. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2014, 121, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keltner, N.L.; McAfee, K.M.; Taylor, C.L. Mechanisms and treatments of SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2002, 38, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montejo, A.L.; Montejo, L.; Navarro-Cremades, F. Sexual side-effects of antidepressant and antipsychotic drugs. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2015, 28, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luft, M.J.; Dobson, E.T.; Levine, A.; Croarkin, P.E.; Strawn, J.R. Pharmacologic interventions for antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of trials using the Arizona sexual experience scale. CNS Spectrums 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montejo, A.L.; Prieto, N.; de Alarcón, R.; Casado-Espada, N.; de la Iglesia, J.; Montejo, L. Management Strategies for Antidepressant-Related Sexual Dysfunction: A Clinical Approach. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goodwin, G.M. Revisiting Treatment Options for Depressed Patients with Generalised Anxiety Disorder. Adv. Ther. 2021, 38 (Suppl. 2), 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ljubic, N.; Ueberberg, B.; Grunze, H.; Assion, H.-J. Treatment of bipolar disorders in older adults: A review. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2021, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signorelli, M.S.; Costanzo, M.C.; Cinconze, M.; Concerto, C. What kind of diagnosis in a case of mobbing: Post-traumatic stress disorder or adjustment disorder? BMJ Case Rep. 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, T.; Phillips, N.J.; Stein, D.J.; Ipser, J.C. Pharmacotherapy for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 3, Cd002795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signorelli, M.S.; Concerto, C.; Battaglia, E.; Costanzo, M.C.; Battaglia, F.; Aguglia, E. Venlafaxine augmentation with agomelatine in a patient with obsessive-compulsive disorder and suicidal behaviors. SAGE Open Med. Case Rep. 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sarris, J.; Ravindran, A.; Yatham, L.N.; Marx, W.; Rucklidge, J.J.; McIntyre, R.S.; Akhondzadeh, S.; Benedetti, F.; Caneo, C.; Cramer, H.; et al. Clinician guidelines for the treatment of psychiatric disorders with nutraceuticals and phytoceuticals: The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) and Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Taskforce. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Concerto, C.; Boo, H.; Hu, C.; Sandilya, P.; Krish, A.; Chusid, E.; Coira, D.; Aguglia, E.; Battaglia, F. Hypericum perforatum extract modulates cortical plasticity in humans. Psychopharmacology 2018, 235, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mineo, L.; Concerto, C.; Patel, D.; Mayorga, T.; Paula, M.; Chusid, E.; Aguglia, E.; Battaglia, F. Valeriana officinalis Root Extract Modulates Cortical Excitatory Circuits in Humans. Neuropsychobiology 2017, 75, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concerto, C.; Infortuna, C.; Muscatello, M.R.A.; Bruno, A.; Zoccali, R.; Chusid, E.; Aguglia, E.; Battaglia, F. Exploring the effect of adaptogenic Rhodiola Rosea extract on neuroplasticity in humans. Complement. Ther. Med. 2018, 41, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennisi, M.; Lanza, G.; Cantone, M.; D’Amico, E.; Fisicaro, F.; Puglisi, V.; Vinciguerra, L.; Bella, R.; Vicari, E.; Malaguarnera, G. Acetyl-L-Carnitine in Dementia and Other Cognitive Disorders: A Critical Update. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisicaro, F.; Lanza, G.; Pennisi, M.; Vagli, C.; Cantone, M.; Pennisi, G.; Ferri, R.; Bella, R. Moderate Mocha Coffee Consumption Is Associated with Higher Cognitive and Mood Status in a Non-Demented Elderly Population with Subcortical Ischemic Vascular Disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisicaro, F.; Lanza, G.; Pennisi, M.; Vagli, C.; Cantone, M.; Falzone, L.; Pennisi, G.; Ferri, R.; Bella, R. Daily mocha coffee intake and psycho-cognitive status in non-demented non-smokers subjects with subcortical ischaemic vascular disease. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, G.; Godos, J.; Privitera, A.; Lanza, G.; Castellano, S.; Chillemi, A.; Bruni, O.; Ferri, R.; Caraci, F.; Grosso, G. Phenolic Acids and Prevention of Cognitive Decline: Polyphenols with a Neuroprotective Role in Cognitive Disorders and Alzheimer’s Disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, E.K. Nutraceutical—Definition and introduction. AAPS Pharm. Sci. 2003, 5, E25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vitale, S.G.; La Rosa, V.L.; Petrosino, B.; Rodolico, A.; Mineo, L.; Laganà, A.S. The Impact of Lifestyle, Diet, and Psychological Stress on Female Fertility. Oman Med. J. 2017, 32, 443–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.; Ibarra, A.; Roller, M.; Zangara, A.; Stevenson, E. A pilot investigation into the effect of maca supplementation on physical activity and sexual desire in sportsmen. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 126, 574–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenico, T.; Cicero, A.F.G.; Valmorri, L.; Mercuriali, M.; Bercovich, E. Subjective effects of Lepidium meyenii(Maca) extract on well-being and sexual performances in patients with mild erectile dysfunction: A randomised, double-blind clinical trial. Andrologia 2009, 41, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Peres, N.D.; Cabrera, L.P.B.; Medeiros, L.L.M.; Formigoni, M.; Fuchs, R.H.B.; Droval, A.A.; Reitz, F.A.C. Medicinal effects of Peruvian maca (Lepidium meyenii): A review. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki-Saghooni, N.; Mirzaii, K.; Hosseinzadeh, H.; Sadeghi, R.; Irani, M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials on saffron (Crocus sativus) effectiveness and safety on erectile dysfunction and semen parameters. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 2018, 8, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy, A.A.; Priya, V.H.; Kumaran, A. Medicinal plants as a potential source of Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 267, 113536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meston, C.M.; Rellini, A.H.; Telch, M.J. Short- and Long-term Effects of Ginkgo Biloba Extract on Sexual Dysfunction in Women. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2008, 37, 530–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Silva, T.; Jesus, M.; Cagigal, C.; Silva, C. Food with Influence in the Sexual and Reproductive Health. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2019, 20, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayebi, N.; Khalili, N.; Kamalinejad, M.; Emtiazy, M. A systematic review of the efficacy and safety of Rosa damascena Mill. with an overview on its phytopharmacological properties. Complement. Ther. Med. 2017, 34, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dording, C.M.; Fisher, L.; Papakostas, G.; Farabaugh, A.; Sonawalla, S.; Fava, M.; Mischoulon, D. A Double-Blind, Randomized, Pilot Dose-Finding Study of Maca Root (L. Meyenii) for the Management of SSRI-Induced Sexual Dysfunction. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2008, 14, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dording, C.; Mischoulon, D.; Shyu, I.; Alpert, J.; Papakostas, G. SAMe and sexual functioning. Eur. Psychiatry 2012, 27, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dording, C.M.; Schettler, P.J.; Dalton, E.D.; Parkin, S.R.; Walker, R.S.W.; Fehling, K.B.; Fava, M.; Mischoulon, D. A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial of Maca Root as Treatment for Antidepressant-Induced Sexual Dysfunction in Women. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 949036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farnia, V.; Hojatitabar, S.; Shakeri, J.; Rezaei, M.; Yazdchi, K.; Bajoghli, H.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E.; Brand, S. Adjuvant Rosa Damascena has a Small Effect on SSRI-induced Sexual Dysfunction in Female Patients Suffering from MDD. Pharmacopsychiatry 2015, 48, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnia, V.; Shirzadifar, M.; Shakeri, J.; Rezaei, M.; Bajoghli, H.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E.; Brand, S. Rosa damascena oil improves SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction in male patients suffering from major depressive disorders: Results from a double-blind, randomized, and placebo-controlled clinical trial. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kang, B.-J.; Lee, S.-J.; Kim, M.-D.; Cho, M.-J. A placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of Ginkgo biloba for antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction. Hum. Psychopharmacol. Clin. Exp. 2002, 17, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashani, L.; Raisi, F.; Saroukhani, S.; Sohrabi, H.; Modabbernia, A.; Nasehi, A.-A.; Jamshidi, A.; Ashrafi, M.; Mansouri, P.; Ghaeli, P.; et al. Saffron for treatment of fluoxetine-induced sexual dysfunction in women: Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2013, 28, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelson, D.; Kociban, K.; Tamura, R.; Morrison, M.F. Mirtazapine, yohimbine or olanzapine augmentation therapy for serotonin reuptake-associated female sexual dysfunction: A randomized, placebo controlled trial. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2002, 36, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modabbernia, A.; Sohrabi, H.; Nasehi, A.-A.; Raisi, F.; Saroukhani, S.; Jamshidi, A.; Tabrizi, M.; Ashrafi, M.; Akhondzadeh, S. Effect of saffron on fluoxetine-induced sexual impairment in men: Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Psychopharmacology 2012, 223, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, D. Triple-blind, placebo-controlled trial of Ginkgo biloba in sexual dysfunction due to antidepressant drugs. Hum. Psychopharmacol. Clin. Exp. 2004, 19, 545–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beharry, S.; Heinrich, M. Is the hype around the reproductive health claims of maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp.) justified? J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 211, 126–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chain, F.E.; Grau, A.; Martins, J.C.; Catalán, C.A. Macamides from wild ‘Maca’, Lepidium meyenii Walpers (Brassicaceae). Phytochem. Lett. 2014, 8, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCollom, M.M.; Villinski, J.R.; McPhail, K.L.; Craker, L.E.; Gafner, S. Analysis of macamides in samples of Maca (Lepidium meyenii) by HPLC-UV-MS/MS. Phytochem. Anal. 2005, 16, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meissner, H.O.; Kapczynski, W.; Mscisz, A.; Lutomski, J. Use of Gelatinized Maca (Lepidium Peruvianum) in Early Postmenopausal Women. Int. J. Biomed. Sci. IJBS 2005, 1, 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, G.; Cordova, A.; Gonzales, C.; Chung, A.; Vega, K.; Villena, A. Lepidium meyenii (Maca) improved semen parameters in adult men. Asian J. Androl. 2001, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, G.F.; Cordova, A.; Vega, K.; Chung, A.; Villena, A.; Gonez, C.; Castillo, S. Effect of Lepidium meyenii (MACA) on sexual desire and its absent relationship with serum testosterone levels in adult healthy men. Andrologia 2002, 34, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, S.C. S-adenosylmethionine. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2000, 32, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, K.-E. Mechanisms of Penile Erection and Basis for Pharmacological Treatment of Erectile Dysfunction. Pharmacol. Rev. 2011, 63, 811–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjbar, H.; Ashrafizaveh, A. Effects of saffron (Crocus sativus) on sexual dysfunction among men and women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 2019, 9, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hosseinzadeh, H.; Ziaee, T.; Sadeghi, A. The effect of saffron, Crocus sativus stigma, extract and its constituents, safranal and crocin on sexual behaviors in normal male rats. Phytomedicine 2008, 15, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamsa, A.; Hosseinzadeh, H.; Molaei, M.; Shakeri, M.T.; Rajabi, O. Evaluation of Crocus sativus L. (saffron) on male erectile dysfunction: A pilot study. Phytomedicine 2009, 16, 690–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseinzadeh, H.; Jahanian, Z. Effect of Crocus sativus L.(saffron) stigma and its constituents, crocin and safranal, on morphine withdrawal syndrome in mice. Phytother. Res. Int. J. Devoted Pharmacol. Toxicol. Eval. Nat. Prod. Deriv. 2010, 24, 726–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author, Year (Country) Study Design Recruitment Timing Treatment Duration Follow-Up Study Population Characteristics | Interventions | Efficacy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tolerability | |||

| Dording C. M et al., 2008 [35] (USA) Design: double-blind, randomized parallel group Recruitment Timing: April 2005–February 2006 Treatment duration: 12 weeks Follow-up: not reported Participants. 20 (10 low dose; 10 high-dose) Female/Male: 17/3 Mean Age (SD): 36 (13) Diagnosis: major depressive disorder Clinical Status: remitted depressed outpatients with sexual dysfunctions (SD) Cause of disfunctions: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI)-induced SD | Maca Root (high dose) Dose scheme: 6 capsules of 500 mg/day Application: Pills Maca root (low dose) Dose scheme: 6 capsules of 250 mg/day Application: Pills | Efficacy Measures: Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale (ASEX) and Massachusetts General Hospital-Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (MGH-SFQ) Results: ITT subjects on high dose Maca showed an improvement in ASEX and MGH-SFQ scales Libido improved for both ITT and completers groups. | |

| Tolerability Well tolerated overall Adverse effect reported:

| |||

| Dording C.M. et al., 2015 [37] (USA) Design: double-blind placebo-controlled trial Recruitment Timing: December 2007- June 2010 Treatment duration: 12 weeks Follow-up: 3 months Participants: 42 (21 maca; 21 placebo) Female/Male: only female Mean Age (SD): 41.5812.5) Diagnosis: major depressive disorder Clinical Status: remitted depressed outpatients with antidepressant induced sexual dysfunction (AISD) Cause of disfunctions: SSRI -induced SD | Maca Root 1500 mg Dose scheme: 1500 mg bid Application: not reported Placebo Application: not reported | Efficacy Measures: ASEX and MGH-SFQ Results: mean change in total ASEX and MGH-SFQ scores was not significantly different for the maca versus the placebo groups, either overall or within premenopausal or postmenopausal subgroups. Change in testosterone level correlated significantly with improvements in sexual functioning in the maca group. | |

| Tolerability Three subjects discontinued Adverse events reported:

| |||

| Dording, C.M. et al., 2012 [36] (USA) Design: randomized, double-blind trial Recruitment Timing: not reported Treatment duration: 6 weeks Follow-up: not reported Participants: 58 (31 SAMe; 27 placebo) Female/Male: 34/24 Mean Age (SD): SAMe 51(14.2); Placebo 48 (9.7) Diagnosis: major depressive disorder Clinical Status: SSRI/SNRI non-responders depressed patients Cause of disfunctions: SSRI/SNRI-induced SD | S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe) 800 mg Dose scheme: two 400 mg SAMe pills daily for 2 weeks then doubled Application: pills Placebo Dose Scheme: two dummy pills daily, each identical to a 400 mg pill in appearance Application: pills | Efficacy Measures: MGH-SFQ Results: men treated with adjunctive SAMe demonstrated significantly lower arousal dysfunction and erectile dysfunction at endpoint than those treated with adjunctive placebo | |

| Tolerability Tolerability data not reported | |||

| Farnia et al., 2015a [39] (Iran) Design: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial Recruitment Timing: October 2013–June 2014 Treatment duration: 8 weeks Follow-up: 8 weeks after the study started Participants: 60 (30 + 30) Female/Male: only male Mean Age (SD): Rosa Damascena 32.45 (5.68); Placebo 34.02 (6.45) Diagnosis: major depressive disorder (DSM-5 criteria) Clinical Status: outpatient with moderate depression in continuous treatment with SSRI who suffer from SSRI-inducted SD Cause of disfunctions: SSRI/SNRI-induced SD | Rosa Damascena Dose scheme: 2 mL/day (containing 17 mg Citronellol of essential oil of R. damascena) Application: solution Placebo Dose scheme: 2 mL/day (oil–water solution with an identical scent) Application: solution | Efficacy Measures: Brief Sexual Function Inventory (BSFI) Results: SD improved more in the Rosa Damascena group than in the placebo group. Improvements were observed in the Rosa Damascena group from week 4 to week 8 | |

| Tolerability Tolerability data not reported | |||

| Farnia et al., 2015b [38] (Iran) Design: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial Recruitment Timing: October 2013–June 2014 Treatment duration: 8 weeks Follow-up: 8 weeks after the study started Participants: 50 (25 + 25) Female/Male: only female Mean Age (SD): 34 years Diagnosis: major depressive disorder (DSM-5 criteria) Clinical Status: outpatients with acute depressive state stabilized and in continuous treatment with SSRI who suffer from SSRI-inducted SD Cause of disfunctions: SSRI -induced SD | Rosa Damascena Dose scheme: 2 mL/day (containing 17 mg Citronellol of essential oil of R. damascena) Application: solution Placebo Dose scheme: 2 mL/day (oil–water solution with an identical scent) Application: solution | Efficacy Measures: Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) Results: sexual desire, sexual orgasms and sexual satisfaction increased over time. Patients in the Rosa Damascena group reported decreased pain. Overall sexual score increased in the Rosa Damascena as compared to the placebo condition. Data suggest only modest effects of adjuvant Rosa Damascena oil on female sexual function. | |

| Tolerability Tolerability data not reported | |||

| Kang et al., 2002 [40] (South Korea) Design: randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial Recruitment Timing: March 2000–January 2002 Treatment duration: 2 months Follow-up: not reported Participants: 37 (19 GB + 18 P) Female/Male: 10 (4 GB + 6 P)/27 (15 GB + 12 P) Mean Age (SD): 47.31 (10.51) GB–45.50 (8.80) P Diagnosis: substance-induced SD due to antidepressants (DSM-IV criteria) in patients with depressive disorder (without psychotic features) or anxiety disorder Clinical Status: depressive disorder or anxiety disorder being treated with an antidepressant Cause of disfunctions: SSRI and tricyclic-induced SD | Ginkgo Biloba Dose scheme: 120 mg daily for the first 2 weeks, 160 mg for the second 2 weeks, 240 mg was dispensed for 4 weeks thereafter. Application: pills Placebo Dose scheme: same as above but with placebo pills. Application: pills | Efficacy Measures: not validated questionnaire Results: no statistically significant difference was shown between the two groups; in comparison with baseline, both the Ginkgo biloba group and the placebo group showed improvement in some part of the sexual function, which is suggestive of the importance of the placebo effect in assessing sexual function. | |

| Tolerability Well tolerated; only few patients complained of:

| |||

| Wheatley D. 2004 [44] (UK) Design: triple-blind (investigator, patient, statistician), randomized, placebo-controlled, trial Recruitment Timing: not reported Treatment duration: 12 weeks Follow-up: 18 weeks Participants: 24 (13 Placebo–11 Gingko Biloba) Female/Male: 5/8 Placebo–5/6 Gingko Biloba Mean Age (SD): 40 Diagnosis: long standing depression Clinical Status: taking any antidepressant drug for at least 2 weeks and experiencing sexual problems Cause of disfunctions: SSRI and tricyclic-induced SD | Gingko Biloba Dose scheme: 125 mg daily for one week before the study to begin, then 250 mg daily Application: pills Placebo Dose scheme: equivalent as above once a day. Application: pills | Efficacy Measures: Sexual Dysfunction Questionnaire (SDQ) Results: there were no significant differences from week 0 at any period of the trial, other than at week 6 in the Ginkgo Biloba group; neither were there any significant between-group differences. There were no significant differences between week 18 and either week 0 or week 12. | |

| Tolerability Low incidence of side effects (no side effects for 10, Ginkgo Biloba patients, nor for 11 placebo patients) One severe side effect with consequent dropout in the placebo group (for night sweats) and three in the Ginkgo Biloba group (for gastric pain; ‘muzzy head’; paresthesia and anesthesia of hands with palpitations) | |||

| Kashani et al. 2012 [41] (Iran) Design: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study conducted in three centers (two private clinics and one hospital outpatient clinic) Recruitment Timing: February 2009–February 2010 Treatment duration: 4 weeks Follow-up: not reported Participants: 38 (19 Saffron–19 Placebo) Female/Male: only female Mean Age (SD): Saffron 34.7 (4.7)–Placebo: 36.0 (6.1) Diagnosis: major depressive disorder (DSM IV criteria) Clinical Status: non responders to antidepressant + in treatment with fluoxetine Cause of distinctions: fluoxetine-induced SD | Saffron Dose scheme: 15 mg twice a day or placebo Application: pills Placebo Dose scheme: same as above Application: pills | Efficacy Measures: FSFI Results: saffron was particularly effective in improving the arousal, lubrication, and intercourse-related pain domains of FSFI. Saffron was shown to be as safe as placebo | |

| Tolerability Well tolerated, no significant differences between the two groups. Side effects reported:

| |||

| Modabbernia et al., 2012 [43] (Iran) Design: randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, parallel-group clinical trial conducted in one hospital outpatient clinic Recruitment Timing: February 2009–December 2011 Treatment duration: 4 weeks Follow-up: not reported Participants: 30 (15 saffron + 15 placebo) Female/Male: only male Mean Age (SD): Saffron 36.6 ± 8.3 Placebo 40.5 ± 9.4 Diagnosis: major depressive disorder (DSM IV criteria) Clinical Status: SD emerged during treatment and documented with a score < 25 on the erectile function domain of International Index of Erectile Function scale (IIEF) Cause of distinctions: fluoxetine-induced SD. | Saffron Dose scheme: 15 mg twice per day or placebo (with the same appearance and taste as saffron capsule) twice per day. Application: pills Placebo Dose scheme: same as above but with placebo pills twice per day. Application: pills | Efficacy Measures: International Index of Erectile Function scale (IIEF) Results: there was evidence for beneficial effects of saffron on fluoxetine-induced SD. This was particularly evident in the erectile and intercourse satisfaction domains of IIEF There was evidence for tolerability and efficacy of saffron in treatment of fluoxetine-related erectile dysfunction. | |

| Tolerability Frequency of side effects did not differ between the two treatment groups. Nine side effects (all mild, none determining dropout):

| |||

| Michelson et al., 2002 [42] (USA) Design: double blind, randomized, parallel, placebo-controlled, multi-site trial Recruitment Timing: not reported Treatment duration: 10-week study consisting of a 4-week baseline evaluation followed by a 6-week treatment period Follow-up: not reported Participants: 148 (Yohimbine 35, Placebo 39, non-nutraceuticals: Mirtazapine 36, Olanzapine 38) Female/Male: only female Mean Age (SD): Yohimbine 35.4 (7.0), Placebo 35.5 (7.0) Diagnosis: major depressive disorder + others (not specified) Clinical Status: patients treated with a stable dose of fluoxetine with a satisfactory response to treatment and either anorgasmia, a marked decrease in ability to reach orgasm, or impaired vaginal lubrication during sexual activity which must have begun after the initiation of fluoxetine therapy Cause of distinctions: SSRI-induced SD | Yohimbine Dose scheme: 5.4 mg/day, 1–2 h before the sexual relations. Dose increased to 10.8 mg/day, after 1 week if tolerated. Application: pills Placebo Dose scheme: 2.5 mg/ day, 1–2 h before the sexual relations. Dose “doubled” daily, after 1 week, if tolerated. Application: pills | Efficacy Measures: Kinsey Ratings of Sexual Function—modified (KRSF) Results: no drug assessed was consistently associated with differences from placebo. The results of the study do not support uncontrolled reports of efficacy for these agents in premenopausal women. | |

| Tolerability Patients treated with yohimbine did not discontinue the treatment more frequently than placebo ones (placebo 5% and yohimbine 11%). Side effects of intervention groups were reported aggregated for all the treatment groups, and those with frequency higher than 10% and statistically significantly different from placebo were:

| |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Concerto, C.; Rodolico, A.; Meo, V.; Chiappetta, D.; Bonelli, M.; Mineo, L.; Saitta, G.; Stuto, S.; Signorelli, M.S.; Petralia, A.; et al. A Systematic Review on the Effect of Nutraceuticals on Antidepressant-Induced Sexual Dysfunctions: From Basic Principles to Clinical Applications. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 3335-3350. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb44080230

Concerto C, Rodolico A, Meo V, Chiappetta D, Bonelli M, Mineo L, Saitta G, Stuto S, Signorelli MS, Petralia A, et al. A Systematic Review on the Effect of Nutraceuticals on Antidepressant-Induced Sexual Dysfunctions: From Basic Principles to Clinical Applications. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2022; 44(8):3335-3350. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb44080230

Chicago/Turabian StyleConcerto, Carmen, Alessandro Rodolico, Valeria Meo, Donatella Chiappetta, Marina Bonelli, Ludovico Mineo, Giulia Saitta, Sebastiano Stuto, Maria Salvina Signorelli, Antonino Petralia, and et al. 2022. "A Systematic Review on the Effect of Nutraceuticals on Antidepressant-Induced Sexual Dysfunctions: From Basic Principles to Clinical Applications" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 44, no. 8: 3335-3350. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb44080230

APA StyleConcerto, C., Rodolico, A., Meo, V., Chiappetta, D., Bonelli, M., Mineo, L., Saitta, G., Stuto, S., Signorelli, M. S., Petralia, A., Lanza, G., & Aguglia, E. (2022). A Systematic Review on the Effect of Nutraceuticals on Antidepressant-Induced Sexual Dysfunctions: From Basic Principles to Clinical Applications. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 44(8), 3335-3350. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb44080230