Adoptive Immunotherapy for Hematological Malignancies Using T Cells Gene-Modified to Express Tumor Antigen-Specific Receptors

Abstract

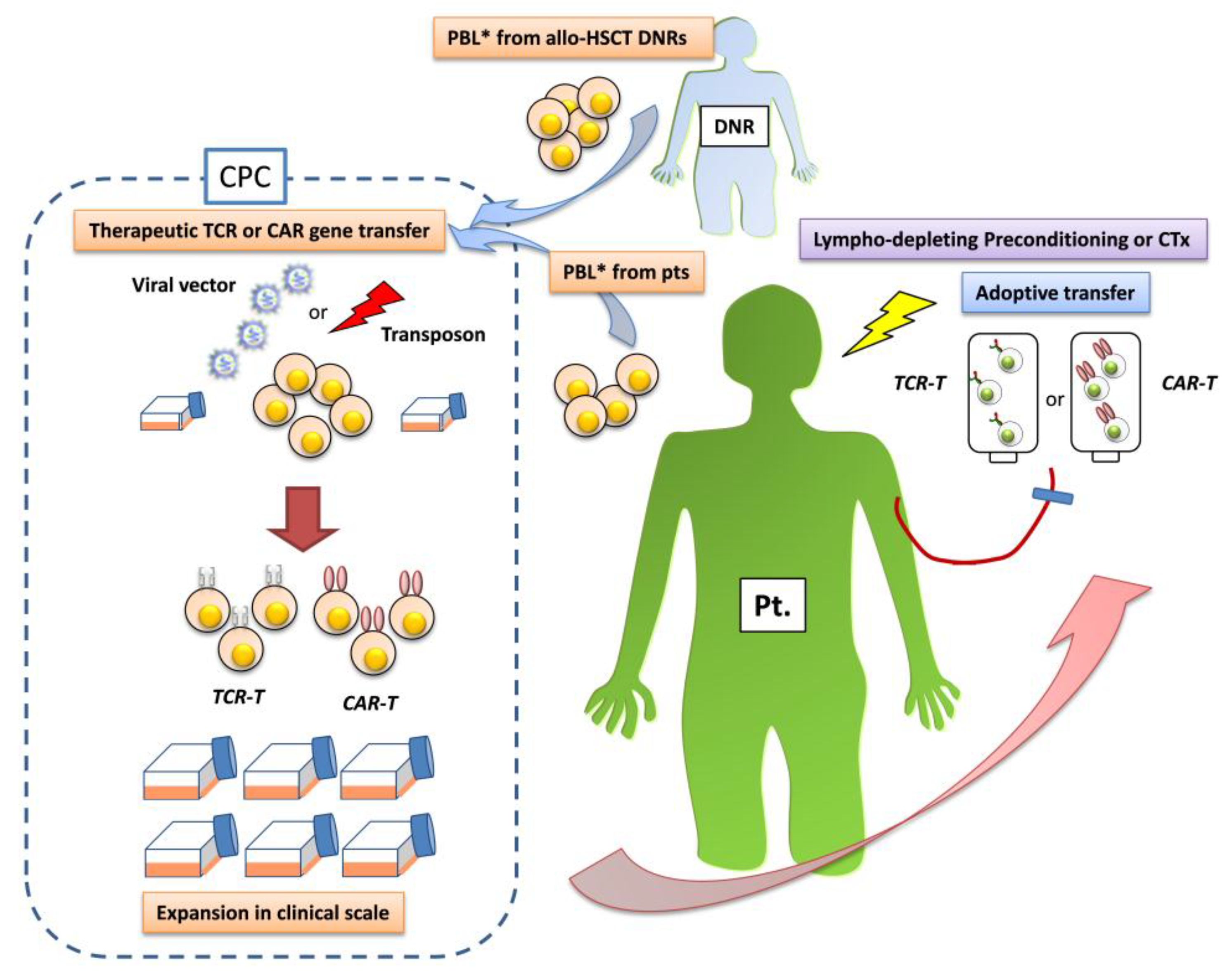

:1. Introduction

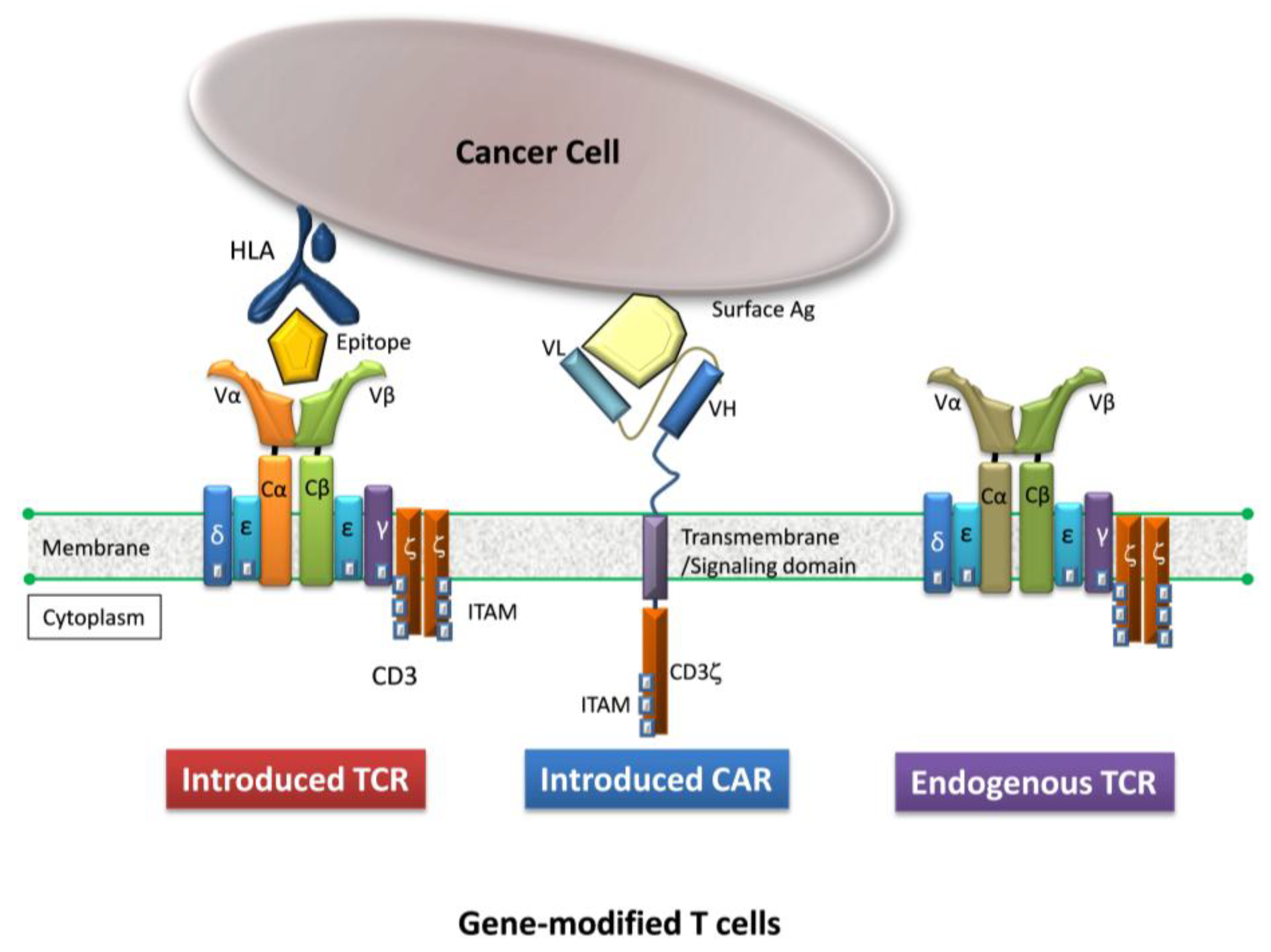

2. Gene-Modified T Cells Redirected Towards Therapeutic Targets

| Taregt Ag. of TCR | Cell Dose (× 109) | Target Disease Pt.No. (n) | Preconditioning | AEs (Grade) | Clinical Responses | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MART-1 | 1.0–86 | melanoma | Cy + Flud | No | PR 2/17 | [37] |

| (n = 17) | ||||||

| MART-1* | 1.5–107 | melanoma (20) | Cy + Flud | skin, eye (G2) | PR 6/20 | [27] |

| gp100** | 1.8–110 | melanoma (16) | ear (G3) | CR 1/16,PR 2/16 | ||

| (n = 36) | ||||||

| p53**/gp100** | 0.5–27.7 | breast ca. (4) | Cy + Flud | N/A | PR 1/9 | [38] |

| melanoma (2) | ||||||

| esoph.ca. (1) | ||||||

| others (2) | ||||||

| CEA* | 0.2–0.4 | colorectal ca. | Cy + Flud | colitis (G3) | PR 1/3 | [28] |

| (n = 3) | CEA decreased 3/3 | |||||

| NY-ESO-1* | 1.6–130 | melanoma (11) | Cy + Flud | No | CR 2/11, PR 3/11 | [29] |

| synovial cell ca.(6) | PR 4/6 | |||||

| (n = 17) | ||||||

| MAGE-A3* | 29–79 | melanoma (7) | Cy + Flud | mental disturbance (G4) | Tumor regression | [25] |

| synovial cell ca.(1) | 2/3 died of necrotizing | 5/9 | ||||

| esoph.ca. (1) | leukoencephalopathy | |||||

| (n = 9) | (on-target AE) | |||||

| MAGE-A3* | 5.3 & 2.4 | melonoma (1) | Cy | 2/2 died of cardiogenic | NE | [26] |

| myeloma (1) | melphalan + autoSCT | shock | ||||

| (n = 2) | (off-target AE) | |||||

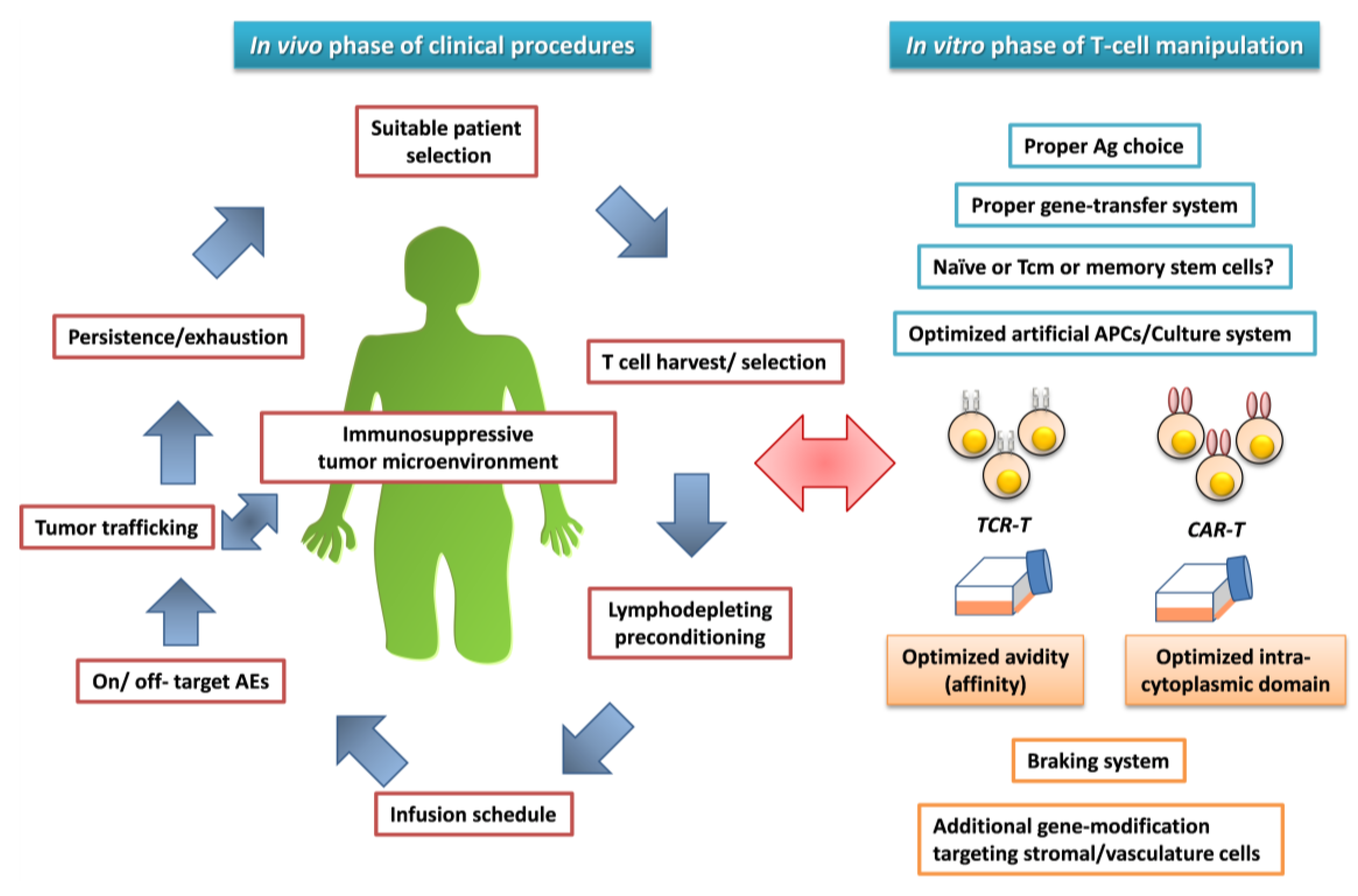

3. Lessons from Clinical Trials Using T Cells Gene-Modified by Tumor Antigen-Specific Receptor Gene Transfer

| Target Ag. of CAR | Cell Dose | Target disease Pt.No. (n) | Preconditioning | AEs (Grade) | Clinical Responses | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1-cell adhesion | 1 × 108 | neuroblastoma (6) | none | pancytopenia (G3) | PR 1/6 | [64] |

| molecule/CAR* | Or 109/m2 | bacteremia, pneumonitis | ||||

| HER2/CAR** | 1 × 101° | colon cancer with | Cy + Flud | died of acute pulmonary | N/E | [65] |

| lung/liver meta. (1) | failure | |||||

| GD2/CAR* | 0.2–0.5–1 | neuroblastoma (19) | none | no | CR 3/19, PR 1/19 | [66] |

| EBV-CTL | × 108 | |||||

| CD19/CAR*** | 1.1 × 109 | CLL (3) | CTx for CLL | lymphopenia (G3) | CR | [51] |

| 5.8 × 108 | B cell aplasia | PR | ||||

| 1.4 × 107 | CR | |||||

| CD19/CAR# | 1.0–11.1 | CLL (8) | none for 3 | hypotension (G3) | PR 1/8 in CLL | [53] |

| × 109 | ALL (2) | Cy (1500 mg or 3000 mg) | 1 died of shock, renal failure | B cell aplasia | ||

| for others | B cell aplasia | |||||

| CD19/CAR# | 0.5–5.5 | CLL (4) | Cy + Flud | hypotension (G3/4) | CR 1/4, PR 2/4 in CLL | [52] |

| × 107 /Kg | FL (4) | renal failure, infection | PR 3/4 in FL | |||

| B cell aplasia | B cell aplasia | |||||

| CD20/CAR** | 4.4 × 109 /m2 | MCL (2) | Cy (1000 mg/m2 ) | hypoxia (G3), fever (G2) | PR in FL | [67] |

| FL (1) | ||||||

| CD19/CAR# | 1.0–11.1 | B-ALL (5) | Cy (1500 mg or 3000 mg) | fever (G2) | CR 2/6 (no MRD) | [54] |

| × 106 /Kg | ||||||

| CD19/CAR*** | 1.4–12 | ALL (2) | CTx for ALL | CRS (G3-4) | CR 2/2 | [55] |

| × 106 /Kg | B cell aplasia | |||||

| CD19/CAR # | 3 × 106 /kg | refractory B-ALL (16) | Cy (1500 mg or 3000 mg) | CRS (G3-4) (7/16) | CR 14/16 | [56] |

| ph+ (4/16) | neurologic complication (3/7) | molecular CR 10/14 | ||||

| respiratory ventilation (3/3) | transit to allo-HSCT | |||||

| (7/14) |

4. Adverse Effects of Gene-Modified T Cells

5. Attempts to Address Challenging Issues

6. Conlusions

Conflict of Interest

References

- Miller, J.S.; Warren, E.H.; van den Brink, M.R.; Ritz, J.; Shlomchik, W.D.; Murphy, W.J.; Barrett, A.J.; Kolb, H.J.; Giralt, S.; Bishop, M.R.; et al. NCI First International Workshop on The Biology, Prevention, and Treatment of Relapse After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: Report from the Committee on the Biology Underlying Recurrence of Malignant Disease following Allogeneic HSCT: Graft-versus-Tumor/Leukemia Reaction. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010, 16, 565–586. [Google Scholar]

- Blyth, E.; Clancy, L.; Simms, R.; Ma, C.K.; Burgess, J.; Deo, S.; Byth, K.; Dubosq, M.C.; Shaw, P.J.; Michlethwaite, K.P.; et al. Donor-derived CMV-specific T cells reduce the requirement for CMV-directed pharmacotherapy after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood 2013, 121, 3745–3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, S.A.; Dudley, M.E. Adoptive cell therapy for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2009, 21, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudley, M.E.; Yang, J.C.; Sherry, R.; Hughes, M.S.; Royal, R.; Kammula, U.; Robbins, P.F.; Huang, J.; Citrin, D.E.; Leitman, S.F.; et al. Adoptive cell therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: Evaluation of intensive myeloablative chemoradiation preparative regimens. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 5233–5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerkar, S.P.; Muranski, P.; Kaiser, A.; Boni, A.; Sanchez-Perez, L.; Yu, Z.; Palmer, D.C.; Reger, R.N.; Borman, Z.A.; Zhang, L.; Morgan, R.A.; et al. Tumor-specific CD8+ T cells expressing interleukin-12 eradicate established cancers in lymphodepleted hosts. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 6725–6734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muranski, P.; Boni, A.; Wrzesinski, C.; Citrin, D.E.; Rosenberg, S.A.; Childs, R.; Restifo, N.P. Increased intensity lymphodepletion and adoptive immunotherapy—How far can we go? Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 2006, 3, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.S.; Soignier, Y.; Panoskaltsis-Mortari, A.; McNearney, S.A.; Yun, G.H.; Fautsch, S.K.; McKenna, D.; Le, C.; Defor, T.E.; Burns, L.J.; et al. Successful adoptive transfer and in vivo expansion of human haploidentical NK cells in patients with cancer. Blood 2005, 105, 3051–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, J.L.; Levine, J.E.; Reddy, P.; Holler, E. Graft-versus-host disease. Lancet 2009, 373, 1550–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besser, M.J.; Shapira-Frommer, R.; Treves, A.J.; Zippel, D.; Itzhaki, O.; Schallmach, E.; Kubi, A.; Shalmon, B.; Hardan, I.; Catane, R.; et al. Minimally cultured or selected autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes after a lympho-depleting chemotherapy regimen in metastatic melanoma patients. J. Immunother. 2009, 32, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vincent, K.; Roy, D.C.; Perreault, C. Next-generation leukemia immunotherapy. Blood 2011, 118, 2951–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamieson, B.D.; Ahmed, R. T cell memory. Long-term persistence of virus-specific cytotoxic T cells. J. Exp. Med. 1989, 169, 1993–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michie, C.A.; McLean, A.; Alcock, C.; Beverly, P.C. Lifespan of human lymphocyte subsets defined by CD45 isoform. Nature 1992, 360, 264–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koya, R.C.; Mok, S.; Comin-Anduix, B.; Chodon, T.; Radu, C.G.; Nishimura, M.I.; Witte, O.N.; Ribas, A. Kinetic phases of distribution and tumor targeting by T cell receptor engineered lymphocytes inducing robust antitumor responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 14286–14291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hildebrandt, M.; Peggs, K.; Uharek, L.; Bollard, C.M.; Heslop, H.E. Immunotherapy: Opportunities, risks and future perspectives. Cytotherapy 2014, 16, S120–S129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, T.S.; Rosenberg, S.A.; Morgan, R.A. Treating cancer with genetically engineered T cells. Trends Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochi, T.; Fujiwara, H.; Yasukawa, M. Requisite considerations for successful adoptive immunotherapy with engineered T-lymphocytes using tumor antigen-specific T-cell receptor gene transfer. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2011, 11, 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au, P.; Hursh, D.A.; Lim, A.; Moos, M.C. Jr.; Oh, S.S.; Schneider, B.S.; Witten, C.M. FDA oversight of cell therapy clinical trials. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 49fs31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, H. Adoptive T-cell therapy for hematological malignancies using T cells gene-modified to express tumor antigen-specific receptors. Int. J. Hematol. 2014, 99, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrigan-Curay, J.; Kiem, H.P.; Baltimore, D.; O'Reilly, M.; Brentjens, R.J.; Cooper, L.; Forman, S.; Gottschalk, S.; Greenberg, P.; Junghans, R.; et al. T-cell immunotherapy: Looking forward. Mol. Ther. 2014, 22, 1564–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- June, C.H. Principles of adoptive T cell cancer therapy. J. Clin. Inv. 2007, 117, 1204–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, T.M.; Aggen, D.H.; Stromnes, I.M.; Dossett, M.L.; Richman, S.A.; Kranz, D.M.; Greenberg, P.D. Enhanced-affinity murine T-cell receptors for tumor/self-antigens can be safe in gene therapy despite surpassing the threshold for thymic selection. Blood 2013, 122, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Moysey, R.; Molloy, P.E.; Vuidepot, A.L.; Mahon, T.; Baston, E.; Dunn, S.; Liddy, N.; Jacob, J.; Jakobsen, B.K.; et al. Directed evolution of human T-cell receptors with picomolar affinities by phage display. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005, 23, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stauss, H.J. Immunotherapy with CTLs restricted by nonself MHC. Immunol. Today 1999, 20, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanislawski, T.; Voss, R.H.; Lotz, C.; Sadovnikova, E.; Willemsen, R.A.; Kuball, J.; Ruppert, T.; Bolhuis, R.L.; Melief, C.J.; Huber, C.; et al. Circumventing tolerance to a human MDM2-derived tumor antigen by TCR gene transfer. Nat. Immunol. 2001, 2, 962–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, R.A.; Chinnasamy, N.; Abate-Daga, D.; Gros, A.; Robbins, P.F.; Zheng, Z.; Dudley, M.E.; Feldman, S.A.; Yang, J.C.; Sherry, R.M.; et al. Cancer regression and neurological toxicity following anti-MAGE-A3 TCR gene therapy. J. Immunother. 2013, 36, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linette, G.P.; Stadtmauer, E.A.; Maus, M.V.; Rapoport, A.P.; Levine, B.L.; Emery, L.; Litzky, L.; Bagg, A.; Carreno, B.M.; Cimino, P.J.; et al. Cardiovascular toxicity and titin cross-reactivity of affinity-enhanced T cells in myeloma and melanoma. Blood 2013, 122, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, L.A.; Morgan, R.A.; Dudley, M.E.; Cassard, L.; Yang, J.C.; Hughes, M.S.; Kammula, U.S.; Royal, R.E.; Sherry, R.M.; Wunderlich, J.R.; et al. Gene therapy with human and mouse T-cell receptors mediates cancer regression and targets normal tissues expressing cognate antigen. Blood 2009, 114, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkhurst, M.R.; Yang, J.C.; Langan, R.C.; Dudley, M.E.; Nathan, D.A.; Feldman, S.A.; Davis, J.L.; Morgan, R.A.; Merino, M.J.; Sherry, M.R.; et al. T cells targeting carcinoembryonic antigen can mediate regression of metastatic colorectal cancer but induce severe transient colitis. Mol. Ther. 2011, 19, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, P.F.; Morgan, R.A.; Feldman, S.A.; Yang, J.C.; Sherry, R.M.; Dudley, M.E.; Wunderlich, J.R.; Nahvi, A.V.; Helman, L.J.; Mackall, C.L.; et al. Tumor regression in patients with metastatic synovial cell sarcoma and melanoma using genetically engineered lymphocytes reactive with NY-ESO-1. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, C.J.; Li, Y.F.; El-Gamil, M.; Robbins, P.F.; Rosenberg, S.A.; Morgan, R.A. Enhanced antitumor activity of T cells engineered to express T-cell receptors with a second disulfide bond. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 3898–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, S.; Xue, S.A.; Cesco-Gaspere, M.; San José, E.; Hart, D.P.; Wong, V.; Debets, R.; Alarcon, B.; Morris, E.; Stauss, H.J. Targeting the Wilms tumor antigen 1 by TCR gene transfer: TCR variants improve tetramer binding but not the function of gene modified human T cells. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 5803–5810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendle, G.M.; Linnemann, C.; Hooijkaas, A.I.; Bies, L.; de Witte, M.A.; Jorritsma, A.; Kaiser, A.D.; Pouw, N.; Debets, R.; Kieback, E.; et al. Lethal graft-versus-host disease in mouse models of T cell receptor gene therapy. Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, S.; Mineno, J.; Ikeda, H.; Fujiwara, H.; Yasukawa, M.; Shiku, H.; Kato, I. Improved expression and reactivity of transduced tumor-specific TCRs in human lymphocytes by specific silencing of endogenous TCR. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 9003–9011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, S.; Amaishi, Y.; Goto, Y.; Ikeda, H.; Fujiwara, H.; Kuzushima, K.; Yasukawa, M.; Shiku, H.; Mineno, J. A Promising Vector for TCR Gene Therapy: Differential Effect of siRNA, 2A Peptide, and Disulfide Bond on the Introduced TCR Expression. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2012, 1, e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Provasi, E.; Genovese, P.; Lombardo, A.; Magnani, Z.; Liu, P.Q.; Reik, A.; Chu, V.; Paschon, D.E.; Zhang, L.; Kuball, J.; et al. Editing T cell specificity towards leukemia by zinc finger nucleases and lentiviral gene transfer. Nat Med. 2012, 18, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torikai, H.; Reik, A.; Liu, P.Q.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Maiti, S.; Huls, H.; Miller, J.C.; Kebriaei, P.; Rabinovitch, B.; et al. A foundation for universal T-cell based immunotherapy: T cells engineered to express a CD19-specific chimeric-antigen-receptor and eliminate expression of endogenous TCR. Blood 2012, 119, 5697–5705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, R.A.; Dudley, M.E.; Wunderlich, J.R.; Hughes, M.S.; Yang, J.C.; Sherry, R.M.; Royal, R.E.; Topalian, S.L.; Kammula, U.S.; Restifo, N.P.; et al. Cancer regression in patients after transfer of genetically engineered lymphocytes. Science 2006, 314, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.L.; Theoret, M.R.; Zheng, Z.; Lamers, C.H.; Rosenberg, S.A.; Morgan, R.A. Development of human anti-murine T-cell receptor antibodies in both responding and nonresponding patients enrolled in TCR gene therapy trials. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 5852–5861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochi, T.; Fujiwara, H.; Okamoto, S.; An, J.; Nagai, K.; Shirakata, T.; Mineno, J.; Kuzushima, K.; Shiku, H.; Yasukawa, M. Novel adoptive T-cell immunotherapy using a WT1-specific TCR vector encoding silencers for endogenous TCRs shows marked antileukemia reactivity and safety. Blood 2011, 118, 1495–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tebas, P.; Stein, D.; Tang, W.W.; Frank, I.; Wang, S.Q.; Lee, G.; Spratt, S.K.; Surosky, R.T.; Giedlin, M.A.; Nichol, G.; et al. Gene editing of CCR5 in autologous CD4 T cells of persons infected with HIV. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadelain, M.; Brentjens, R.; Rivière, I. The basic principles of chimeric antigen receptor design. Cancer Discov. 2013, 3, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irving, B.A.; Weiss, A. The cytoplasmic domain of the T cell receptor zeta chain is sufficient to couple to receptor-associated signal transduction pathways. Cell 1991, 64, 891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eshhar, Z.; Waks, T.; Gross, G.; Schindler, D.G. Specific activation and targeting of cytotoxic lymphocytes through chimeric single chains consisting of antibody-binding domains and the gamma or zeta subunits of the immunoglobulin and T-cell receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 720–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, M.C.; Latouche, J.B.; Krause, A.; Heston, W.D.; Bander, N.H.; Sadelain, M. Cancer patient T cells genetically targeted to prostate-specific membrane antigen specifically lyse prostate cancer cells and release cytokines in response to prostate-specific membrane antigen. Neoplasia 1999, 1, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, N.M.; Trapani, J.A.; Teng, M.W.; Jackson, J.T.; Cerruti, L.; Jane, S.M.; Kershaw, M.H.; Smyth, M.J.; Darcy, P.K. Rejection of syngeneic colon carcinoma by CTLs expressing single-chain antibody receptors codelivering CD28 costimulation. J. Immunol. 2002, 169, 5780–5786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenito, C.; Milone, M.C.; Hassan, R.; Simonet, J.C.; Lakhal, M.; Suhoski, M.M.; Varela-Rohena, A.; Haines, K.M.; Heitjan, D.F.; Albelda, S.M.; et al. Control of large, established tumor xenografts with genetically retargeted human T cells containing CD28 and CD137 domains. Proc. Natl.Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 3360–3365. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hombach, A.A.; Abken, H. Costimulation by chimeric antigen receptors revisited the T cell antitumor response benefits from combined CD28-OX40 signalling. Int. J. Cancer. 2011, 129, 2935–2944. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Finney, H.M.; Akbar, A.N.; Lawson, A.D. Activation of resting human primary T cells with chimeric receptors: Costimulation from CD28, inducible costimulator, CD134, and CD137 in series with signals from the TCR zeta chain. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finney, H.M.; Lawson, A.D.; Bebbington, C.R.; Weir, A.N. Chimeric receptors providing both primary and costimulatory signaling in T cells from a single gene product. J. Immunol. 1998, 161, 2791–2797. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hombach, A.; Wieczarkowiecz, A.; Marquardt, T.; Heuser, C.; Usai, L.; Pohl, C.; Seliger, B.; Abken, H. Tumor-specific T cell activation by recombinant immunoreceptors: CD3 zeta signaling and CD28 costimulation are simultaneously required for efficient IL-2 secretion and can be integrated into one combined CD28/CD3 zeta signaling receptor molecule. J. Immunol. 2001, 167, 6123–6131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalos, M.; Levine, B.L.; Porter, D.L.; Katz, S.; Grupp, S.A.; Bagg, A.; June, C.H. T cells with chimeric antigen receptors have potent antitumor effects and can establish memory in patients with advanced leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3, 95ra73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, D.L.; Levine, B.L.; Kalos, M.; Bagg, A.; June, C.H. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochenderfer, J.N.; Wilson, W.H.; Janik, J.E.; Dudley, M.E.; Stetler-Stevenson, M.; Feldman, S.A.; Maric, I.; Raffeld, M.; Nathan, D.A.; Lanier, B.J.; et al. Eradication of B-lineage cells and regression of lymphoma in a patient treated with autologous T cells genetically engineered to recognize CD19. Blood 2010, 116, 4099–4102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brentjens, R.J.; Davila, M.L.; Riviere, I.; Park, J.; Wang, X.; Cowell, L.G.; Bartido, S.; Stefanski, J.; Taylor, C.; Olszewska, M.; et al. CD19-targeted T cells rapidly induce molecular remissions in adults with chemotherapy-refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 177ra38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, M.C.; Popplewell, L.; Cooper, L.J.; DiGiusto, D.; Kalos, M.; Ostberg, J.R.; Forman, S.J. Antitransgene rejection responses contribute to attenuated persistence of adoptively transferred CD20/CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor redirected T cells in humans. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010, 16, 1245–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davila, M.L.; Riviere, I.; Wang, X.; Bartido, S.; Park, J.; Curran, K.; Chung, S.S.; Stefanski, J.; Borquez-Ojeda, O.; Olszewska, M.; et al. Efficacy and toxicity management of 19–28z CAR T cell therapy in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 224ra25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilham, D.E.; Debets, R.; Pule, M.; Hawkins, R.E.; Abken, H. T cells and solid tumors: Tuning T cells to challenge an inveterate foe. Trends Mol. Med. 2012, 18, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davila, M.L.; Brentjens, R.; Wang, X.; Rivière, I.; Sadelain, M. How do CARs work? : Early insights from recent clinical studies targeting CD19. Oncoimmunology 2012, 1, 1577–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochenderfer, J.N.; Dudley, M.E.; Feldman, S.A.; Wilson, W.H.; Spaner, D.E.; Maric, I.; Stetler-Stevenson, M.; Phan, G.Q.; Hughes, M.S.; Sherry, R.M.; et al. B-cell depletion and remissions of malignancy along with cytokine-associated toxicity in a clinical trial of anti-CD19 chimeric-antigen-receptor-transduced T cells. Blood 2012, 119, 2709–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savoldo, B.; Ramos, C.A.; Liu, E.; Mims, M.P.; Keating, M.J.; Carrum, G.; Kamble, R.T.; Bollard, C.M.; Gee, A.P.; Mei, Z.; et al. CD28 costimulation improves expansion and persistence of chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in lymphoma patients. J. Clin. Invest. 2011, 121, 1822–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grupp, S.A.; Kalos, M.; Barrett, D.; Aplenc, R.; Porter, D.L.; Rheingold, S.R.; Teachey, D.T.; Chew, A.; Hauck, B.; Wright, J.F.; et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for acute lymphoid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1509–1518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chmielewski, M.; Hombach, A.; Heuser, C.; Adams, G.P.; Abken, H. T cell activation by antibody-like immunoreceptors: Increase in affinity of the single-chain fragment domain above threshold does not increase T cell activation against antigen-positive target cells but decreases selectivity. J. Immunol. 2004, 173, 7647–7653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, A.H.; Haso, W.M.; Orentas, R.J. Lessons learned from a highly-active CD22-specific chimeric antigen receptor. Oncoimmunology 2013, 2, e23621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.R.; Digiusto, D.L.; Slovak, M.; Wright, C.; Naranjo, A.; Wagner, J.; Meechoovet, H.B.; Bautista, C.; Chang, W.C.; Ostberg, J.R.; et al. Adoptive transfer of chimeric antigen receptor re-directed cytolytic T lymphocyte clones in patients with neuroblastoma. Mol. Ther. 2007, 15, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Morgan, R.A.; Yang, J.C.; Kitano, M.; Dudley, M.E.; Laurencot, C.M.; Rosenberg, S.A. Case report of a serious adverse event following the administration of T cells transduced with a chimeric antigen receptor recognizing ERBB2. Mol. Ther. 2010, 18, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, C.U.; Savoldo, B.; Dotti, G.; Pule, M.; Yvon, E.; Myers, G.D.; Rossig, C.; Russell, H.V.; Diouf, O.; Liu, E.; et al. Antitumor activity and long-term fate of chimeric antigen receptor-positive T cells in patients with neuroblastoma. Blood 2011, 118, 6050–6056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Till, B.G.; Jensen, M.C.; Wang, J.; Qian, X.; Gopal, A.K.; Maloney, D.G.; Lindgren, C.G.; Lin, Y.; Pagel, J.M.; Budde, L.E.; et al. CD20-specific adoptive immunotherapy for lymphoma using a chimeric antigen receptor with both CD28 and 4–1BB domains: Pilot clinical trial results. Blood 2012, 119, 3940–3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheadle, E.J.; Sheard, V.; Rothwell, D.G.; Mansoor, A.W.; Hawkins, R.E.; Gilham, D.E. Differential role of Th1 and Th2 cytokines in autotoxicity driven by CD19-specific second-generation chimeric antigen receptor T cells in a mouse model. J. Immunol. 2014, 192, 3654–3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapuis, A.G.; Ragnarsson, G.B.; Nguyen, H.N.; Chaney, C.N.; Pufnock, J.S.; Schmitt, T.M.; Duerkopp, N.; Roberts, I.M.; Pogosov, G.L.; Ho, W.Y.; et al. Transferred WT1-reactive CD8+ T cells can mediate antileukemic activity and persist in post-transplant patients. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 174ra27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Valitutti, S.; Lanzavecchia, A. Serial triggering of TCRs: A basis for the sensitivity and specificity of antigen recognition. Immunol. Today. 1997, 18, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander-Miller, M.A.; Leggatt, G.R.; Berzofsky, J.A. Selective expansion of high- or low-avidity cytotoxic T lymphocytes and efficacy for adoptive immunotherapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 4102–4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, M.; Oda, S.; Sadahiro, T.; Hirayama, Y.; Tateishi, Y.; Abe, R.; Hirasawa, H. The role of hypercytokinemia in the pathophysiology of tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) and the treatment with continuous hemodiafiltration using a polymethylmethacrylate membrane hemofilter (PMMA-CHDF). Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2009, 40, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brentjens, R.; Yeh, R.; Bernal, Y.; Riviere, I.; Sadelain, M. Treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia with genetically targeted autologous T cells: Case report of an unforeseen adverse event in a phase I clinical trial. Mol. Ther. 2010, 18, 666–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maus, M.V.; Haas, A.R.; Beatty, G.L.; Albelda, S.M.; Levine, B.L.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Kalos, M.; June, C.H. T cells expressing chimeric antigen receptors can cause anaphylaxis in humans. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2013, 1, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, P.F.; Lu, Y.C.; El-Gamil, M.; Li, Y.F.; Gross, C.; Gartner, J.; Lin, J.C.; Teer, J.K.; Cliften, P.; Tycksen, E.; et al. Mining exomic sequencing data to identify mutated antigens recognized by adoptively transferred tumor-reactive T cells. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snauwaert, S.; Vandekerckhove, B.; Kerre, T. Can immunotherapy specifically target acute myeloid leukemic stem cells? Oncoimmunology 2013, 2, e22943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciceri, F.; Bonini, C.; Stanghellini, M.T.; Bondanza, A.; Traversari, C.; Salomoni, M.; Turchetto, L.; Colombi, S.; Bernardi, M.; Peccatori, J.; et al. Infusion of suicide-gene-engineered donor lymphocytes after family haploidentical haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation for leukaemia (the TK007 trial): A non-randomised phase I-II study. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Stasi, A.; Tey, S.K.; Dotti, G.; Fujita, Y.; Kennedy-Nasser, A.; Martinez, C.; Straathof, K.; Liu, E.; Durett, A.G.; Grilley, B.; et al. Inducible apoptosis as a safety switch for adoptive cell therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 1673–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, C.; Jensen, M.C.; Lansdorp, P.M.; Gough, M.; Elliott, C.; Riddell, S.R. Adoptive transfer of effector CD8+ T cells derived from central memory cells establishes persistent T cell memory in primates. J. Clin. Invest. 2008, 118, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinrichs, C.S.; Borman, Z.A.; Cassard, L.; Gattinoni, L.; Spolski, R.; Yu, Z.; Sanchez-Perez, L.; Muranski, P.; Kern, S.J.; Logun, C.; et al. Adoptively transferred effector cells derived from naive rather than central memory CD8+ T cells mediate superior antitumor immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 17469–17474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, M.O.; Hirano, N. Human cell-based artificial antigen-presenting cells for cancer immunotherapy. Immunol. Rev. 2013, 257, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodi, F.S.; O'Day, S.J.; McDermott, D.F.; Weber, R.W.; Sosman, J.A.; Haanen, J.B.; Gonzalez, R.; Robert, C.; Schadendorf, D.; Hassel, J.C.; et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topalian, S.L.; Hodi, F.S.; Brahmer, J.R.; Gettinger, S.N.; Smith, D.C.; McDermott, D.F.; Powderly, J.D.; Carvajal, R.D.; Sosman, J.A.; Atkins, M.B.; et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2443–2454. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brahmer, J.R.; Tykodi, S.S.; Chow, L.Q.; Hwu, W.J.; Topalian, S.L.; Hwu, P.; Drake, C.G.; Camacho, L.H.; Kauh, J.; Odunsi, K.; et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2455–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abate-Daga, D.; Hanada, K.; Davis, J.L.; Yang, J.C.; Rosenberg, S.A.; Morgan, R.A. Expression profiling of TCR-engineered T cells demonstrates overexpression of multiple inhibitory receptors in persisting lymphocytes. Blood 2013, 122, 1399–1410. [Google Scholar]

- Day, C.L.; Kaufmann, D.E.; Kiepiela, P.; Brown, J.A.; Moodley, E.S.; Reddy, S.; Mackey, E.W.; Miller, J.D.; Leslie, A.J.; De Pierres, C.; et al. PD-1 expression on HIV-specific T cells is associated with T-cell exhaustion and disease progression. Nature 2006, 443, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, E.K.; Wang, L.C.; Dolfi, D.V.; Wilson, C.B.; Ranganathan, R.; Sun, J.; Kapoor, V.; Scholler, J.; Puré, E.; Milone, M.C.; et al. Multifactorial T-cell hypofunction that is reversible can limit the efficacy of chimeric antigen receptor-transduced human T cells in solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 4262–4273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fujiwara, H. Adoptive Immunotherapy for Hematological Malignancies Using T Cells Gene-Modified to Express Tumor Antigen-Specific Receptors. Pharmaceuticals 2014, 7, 1049-1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph7121049

Fujiwara H. Adoptive Immunotherapy for Hematological Malignancies Using T Cells Gene-Modified to Express Tumor Antigen-Specific Receptors. Pharmaceuticals. 2014; 7(12):1049-1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph7121049

Chicago/Turabian StyleFujiwara, Hiroshi. 2014. "Adoptive Immunotherapy for Hematological Malignancies Using T Cells Gene-Modified to Express Tumor Antigen-Specific Receptors" Pharmaceuticals 7, no. 12: 1049-1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph7121049

APA StyleFujiwara, H. (2014). Adoptive Immunotherapy for Hematological Malignancies Using T Cells Gene-Modified to Express Tumor Antigen-Specific Receptors. Pharmaceuticals, 7(12), 1049-1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph7121049