Abstract

Viruses replicate inside the cells of an organism and continuously evolve to contend with an ever-changing environment. Many life-threatening diseases, such as AIDS, SARS, hepatitis and some cancers, are caused by viruses. Because viruses have small genome sizes and high mutability, there is currently a lack of and an urgent need for effective treatment for many viral pathogens. One approach that has recently received much attention is aptamer-based therapeutics. Aptamer technology has high target specificity and versatility, i.e., any viral proteins could potentially be targeted. Consequently, new aptamer-based therapeutics have the potential to lead a revolution in the development of anti-infective drugs. Additionally, aptamers can potentially bind any targets and any pathogen that is theoretically amenable to rapid targeting, making aptamers invaluable tools for treating a wide range of diseases. This review will provide a broad, comprehensive overview of viral therapies that use aptamers. The aptamer selection process will be described, followed by an explanation of the potential for treating virus infection by aptamers. Recent progress and prospective use of aptamers against a large variety of human viruses, such as HIV-1, HCV, HBV, SCoV, Rabies virus, HPV, HSV and influenza virus, with particular focus on clinical development of aptamers will also be described. Finally, we will discuss the challenges of advancing antiviral aptamer therapeutics and prospects for future success.

1. Introduction

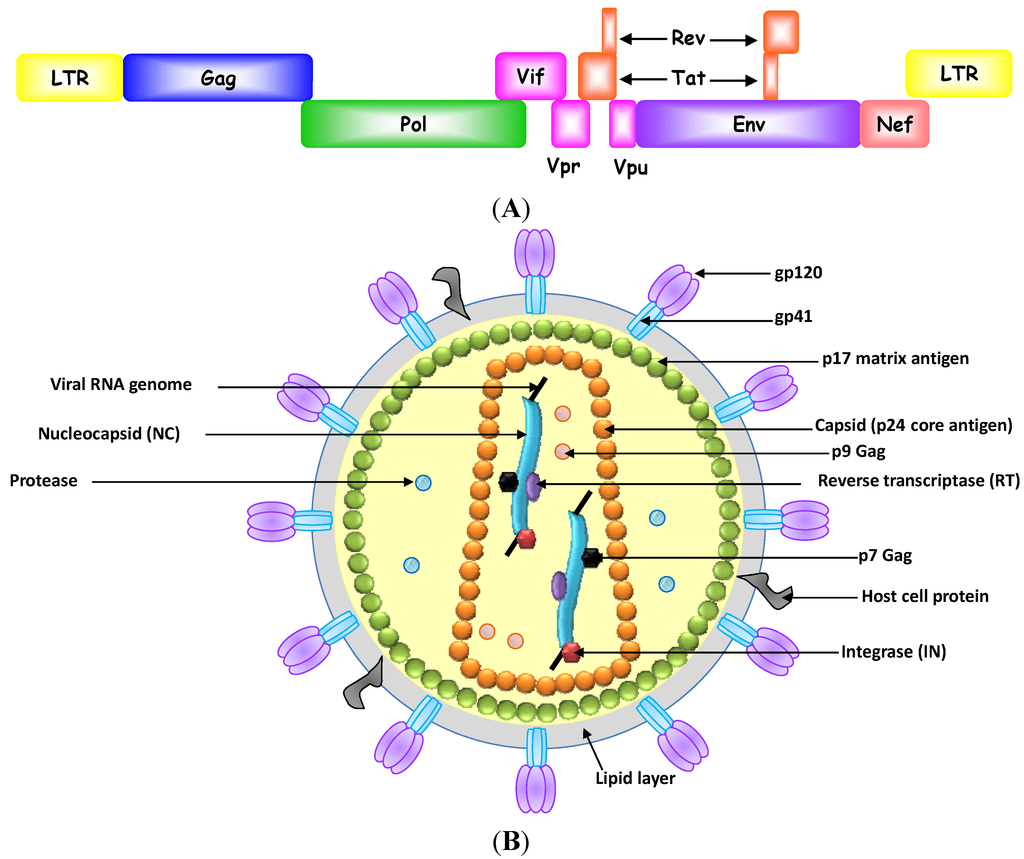

Vaccination is the most effective means to prevent individuals from being infected with pathogenic viruses [1]. However, some viruses, such as HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus, can evade the immune system, and thus impede the effectiveness of vaccines for those viruses [2,3,4]. Therefore, antiviral small molecule inhibitors that inhibit critical steps in the virus lifecycle in infected individuals are critically needed in the battle against virus infections. These inhibitors could curb the virus number in the body by interfering with viral entry into host cells, the function and assembly of viral replication machinery or the release of viruses to infect other cells [5]. Ideally, these antiviral agents should completely eradicate viruses from the body without affecting normal cellular metabolism. However, these features have not yet been achieved because of two main problems associated with use of these drugs: (1) the emergence of resistant viral strains and (2) cytotoxicity to host cells [6,7,8]. Some viruses, such as HIV-1, replicate its genome with high error rate [9]. These mutations in the viral genes that code for surface antigens and enzymes in the replication components often confer drug resistance capabilities to viruses [10]. Also, cytotoxicity often arises because antiviral drugs are usually designed to target and inhibit certain functional motifs of a viral protein. These motifs share a high degree of amino acid sequence similarity across different species and associated with conserved functions. One example demonstrating the motif similarities between viral and human proteins is helicases in which their DEAD-box domain is largely conserved in HCV helicase and human DDX3 RNA helicase [11]. Although off-target cross reactivity often leads to mild side effects, sometimes they are serious and can have a major effect on health. For example, the HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitor 3'-azido-3'-deoxythymidine (zidovudine) is a nucleoside analogue that competes with natural deoxynucleotides (dNTPs) and is incorporated into the growing DNA chain by viral reverse transcriptases. Treatment with zidovudine delays the progression of AIDS, but does not clear the virus because drug resistant mutants usually arise [12,13]. Moreover, long-term, high-dose treatment with zidovudine can cause serious complications, such as anemia, neutropenia, hepatotoxicity, cardiomyopathy and myopathy [12,14,15,16].

Aptamers are in vitro evolved nucleic acids that are capable of performing a specific function [17,18]. The process to identify a functional ligand from a vast population of random sequences is called Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential enrichment (SELEX). Typically, an initial combinatorial library contains a central random region with 30 to 70 nucleotides flanked by a fixed sequence at both ends. The fixed sequence is used for PCR amplification during each SELEX round. Random sequences with at least 1012 entities represent extraordinary molecular diversity and structural complexity to screen high affinity and bioactive aptamers to the target. To date, a dozen of SELEX methodologies have been developed in isolating aptamers against purified proteins or even whole cells (or whole viruses) [19,20,21]. The use of purified proteins as selection targets has the advantage of easy control to achieve optimal sequence enrichment during the SELEX. But whole cell or virus selection is preferred, when the biomarker is unknown. Moreover, since the target protein may be present in a modified form or exist as a protein complex that may be masked and therefore inaccessible to the aptamers, it reflects a more physiological condition when the protein is displayed on the cell surface rather than isolated as purified proteins.

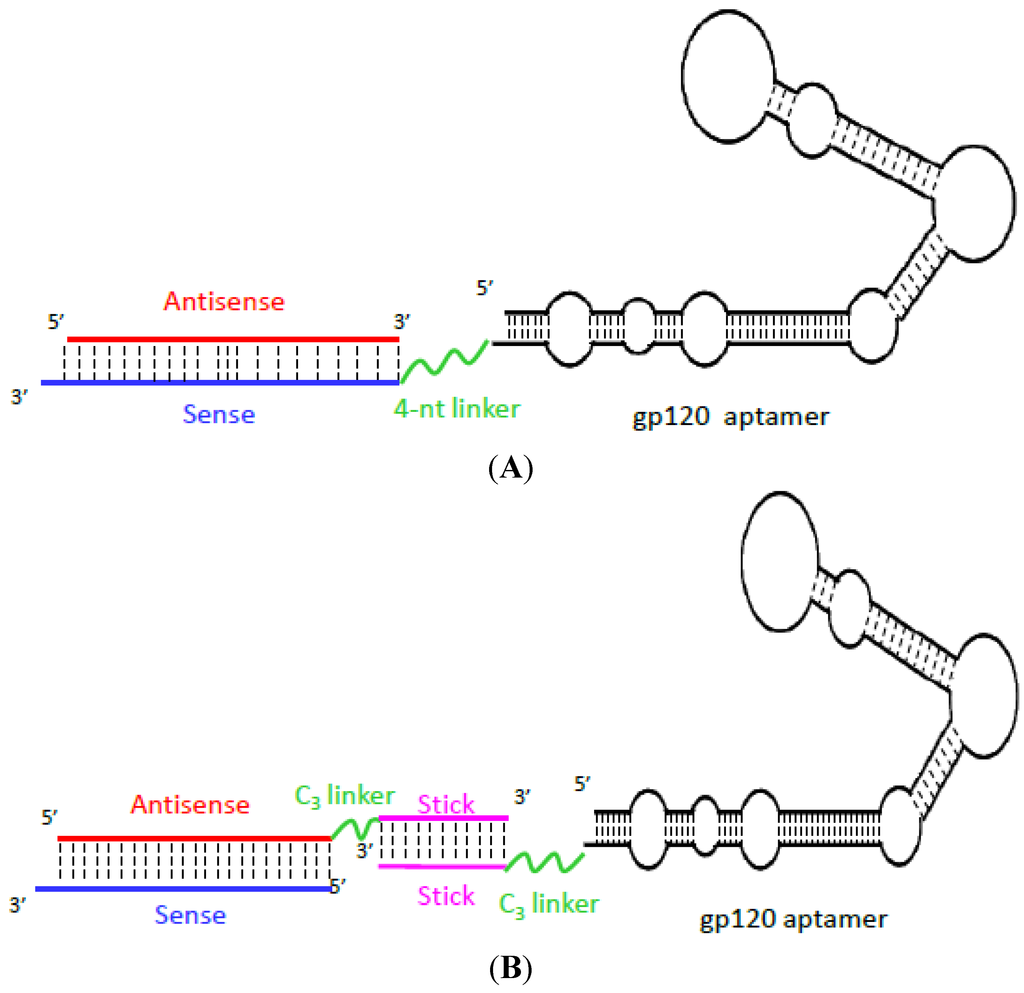

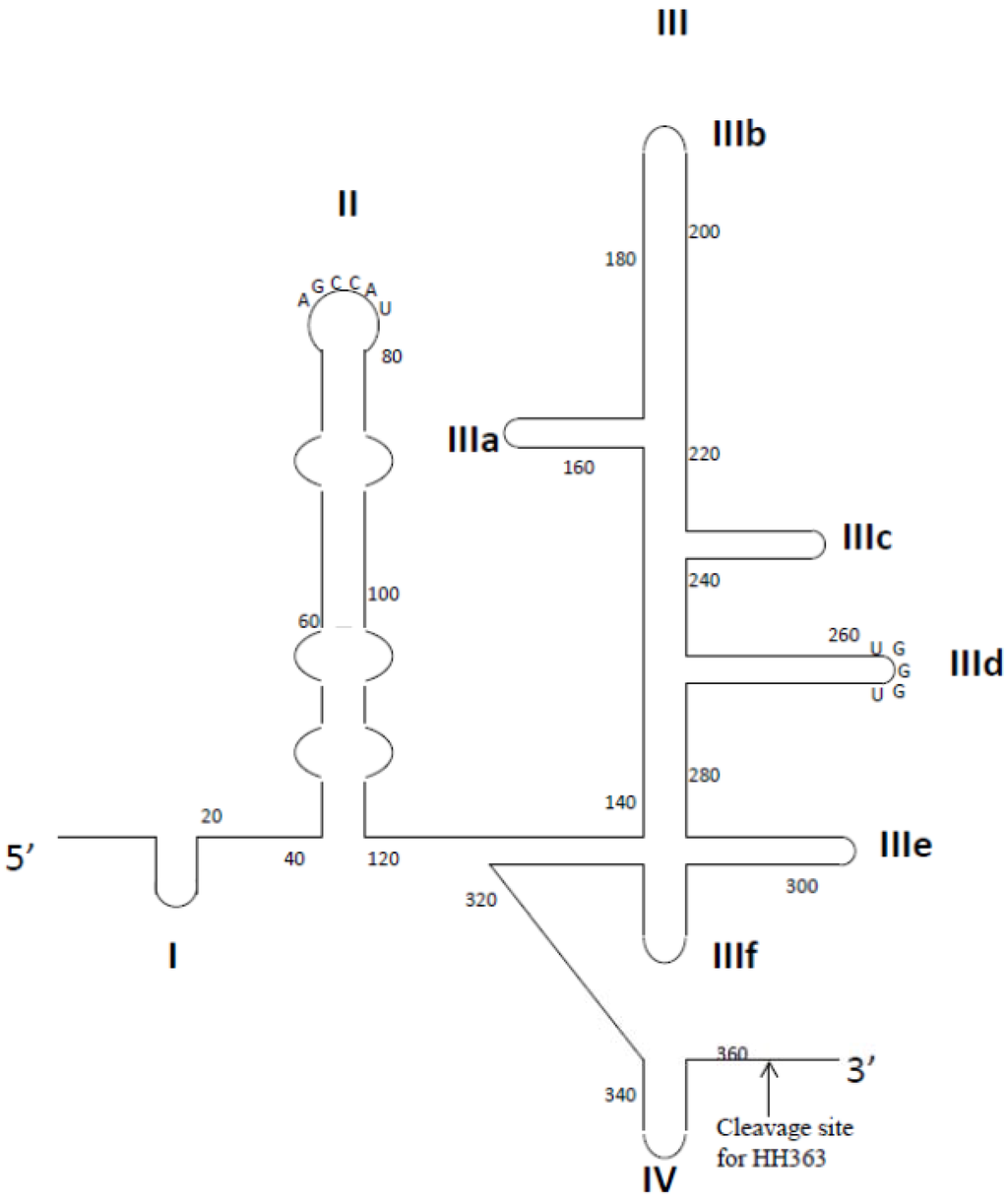

Generally, SELEX comprises of cycles of four sequential steps: (1) binding to the target; (2) partition of target-bound aptamers; (3) recovery of target-bound aptamers; and (4) amplification of recovered sequences [22,23,24]. The selection cycle is complete when a functional aptamer sequence is enriched among the random sequence library. Since the inception of SELEX technology two decades ago, the extraordinary diversity of molecules screened in this manner has led to the discovery of aptamers that bind with exquisite specificity and extraordinary strength [25,26]. Macugen (Pfizer), which is used to treat age-related macular degeneration, was the first aptamer therapeutic approved by United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and has proven to be a milestone in the aptamer history [27,28]. Many novel aptamers are currently being evaluated in clinical trials for treating life-threatening diseases, such as acute myeloid leukemia, renal cell carcinoma, acute coronary syndrome, and choroidal neovascularization [29,30,31,32,33]. In addition, because aptamers can easily be conjugated to chemicals and manufactured, the use of aptamer chimeras for targeted delivery and enhanced potency of secondary agents has progressed rapidly [23,34,35,36,37,38]. In this review, we will focus on the recent progress and prospective use of aptamers against a variety of human viral pathogens; representative examples of aptamer chimeras will be highlighted. Finally, we will discuss the challenges of advancing antiviral aptamer therapeutics and the prospects for future success.

3. Conclusions

Since the first publication of SELEX over two decades ago, the development of aptamer technology has advanced rapidly from the laboratory to early or mid-stage clinical development [210]. Aptamers, also described as chemical versions of antibodies, can inhibit their targets through specific and strong interactions that are superior to those of biologics and small molecule therapeutics, and yet avoid the toxicity and immunogenicity concerns of these traditional agents derived from their nucleic acid compositions [26]. The latest advances in SELEX technology and chemical conjugation methods have given aptamers remarkable potential to be used as “smart bombs” that delivers secondary therapeutic cargos to diseased cells. Several examples (e.g., aptamer-siRNA chimeras, aptamer-ribozyme chimeras and aptamer-aptamer chimeras) discussed in this review demonstrate complementary and versatile approaches for combining the strength of aptamers with other nucleic acid-based therapeutics, offering a polyvalent platform for treating various diseases [23,38,143]. These chimeras offer a huge potential to provide enhanced therapeutic potency and reduced cellular toxicity of the drug. However, despite the substantial advances described above, no aptamers have yet reached clinical development pipeline for antiviral therapy. Aptamers whose targets are expressed intracellularly are unlikely to be used in the clinic because aptamers are hydrophilic and therefore cannot pass through epithelia and the hydrophobic plasma membrane [211]. Consequently, only aptamers that target extracellular viral proteins or capsid proteins of virions, such as HIV-1 gp120 or influenza A HA, are likely to be suitable for clinical therapeutic development [211]. In addition to the aptamer chimera approach, another potential approach to solve this problem would be to use a viral vector that will transiently express the aptamer intracellularly. For example, Bai et al. designed lentiviral vectors that encode anti-HIV ribozymes together with anti-Tat aptamers [51]. The construct was tested in HIV-infected humanized mice and was able to inhibit virus replication [51]. However, it was not conclusive whether the aptamers contributed any inhibitory effect.

Furthermore, as typical nucleic acid entities, naked nucleic acid aptamers are relatively small and are sensitive to nuclease degradation. Their average diameter is usually less than 10 nm, and therefore they are rapidly removed from the blood by renal clearance [44]. Thus, the intrinsic physicochemical features of aptamers pose serious challenges for their transport to infected organs or cells, such as the liver and central nervous system, following systemic administration into the blood stream. Typically, respiratory viruses, such as influenza viruses and SCoV, are well-suited for targeting with aptamer therapeutics because the upper airways and lungs are relatively easy to access as target organs [1]. Therefore, it may be possible to block respiratory virus infections by using an aptamer-containing aerosol [211]. Similarly, sexually transmitted viruses, such as HIV-1 and HPV, might be targeted by intravaginal application of a microbicide or cream that contains the neutralizing aptamers [211]. Although a topical microbicide might protect women against the viruses before the intercourse, the female genital tract is abundant in various nucleases that can degrade nucleic acid aptamers, even the 2' F modified ones, in minutes [212]. One way to improve the aptamer stability is to chemically introduce the 2'-O-Me modifications on the purine nucleotides or phosphorothioate linkages [212]. Moreover, zinc ions can be incorporated into the formulation because nucleases are sensitive to inhibition by zinc ions [212]. Recently, Wheeler et al. developed a topical microbicide containing chemically modified CD4 aptamer-siRNA chimeras that target the HIV co-receptor CCR5, gag and vif for the protection from sexual transmission of HIV-1. The chimeras were stabilized and formulated in a hydroxyethyl cellulose gel, which is a FDA-approved polymer already used in HIV-1 clinical trials, to achieve durable gene knockdown and inhibit HIV-1 transmission in mice [213].

The use of aptamers as therapeutic agents is still in its early stage of development. However, the innovation and flexibility of SELEX methodology will allow aptamer technology to become a major player as an alternative approach in the battle against viral diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank John Burnett and Keely Walker for reading this manuscript. This work was funded by NIH grants RO1AI042552 and RO1 HL074704 awarded to JJR, and U01 CA 151648 awarded to Peixuan Guo (University of Kentucky) and subcontracted to JJR.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Haasnoot, J.; Berkhout, B. Nucleic acids-based therapeutics in the battle against pathogenic viruses. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2009, 189, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mescalchin, A.; Restle, T. Oligomeric nucleic acids as antivirals. Molecules 2011, 16, 1271–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alter, G.; Heckerman, D.; Schneidewind, A.; Fadda, L.; Kadie, C.M.; Carlson, J.M.; Oniangue-Ndza, C.; Martin, M.; Li, B.; Khakoo, S.I.; et al. HIV-1 adaptation to NK-cell-mediated immune pressure. Nature 2011, 476, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Cao, X.; Lu, J.; Huang, B.; Liu, Y.J.; Kato, N.; Shu, H.B.; Zhong, J. Hepatitis C virus NS4B blocks the interaction of STING and TBK1 to evade host innate immunity. J. Hepatol. 2013, 59, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts, E.J.; Hazuda, D.J. HIV-1 antiretroviral drug therapy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a007161. [Google Scholar]

- Gopinath, S.C. Antiviral aptamers. Arch. Virol. 2007, 152, 2137–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordheim, L.P.; Durantel, D.; Zoulim, F.; Dumontet, C. Advances in the development of nucleoside and nucleotide analogues for cancer and viral diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013, 12, 447–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Nunez, M. Liver toxicity of antiretroviral drugs. Semin. Liver Dis. 2012, 32, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, B.D.; Poiesz, B.J.; Loeb, L.A. Fidelity of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Science 1988, 242, 1168–1171. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A.J.; Cleland, A. Independent evolution of the env and pol genes of HIV-1 during zidovudine therapy. AIDS 1996, 10, 1067–1073. [Google Scholar]

- Kwong, A.D.; Rao, B.G.; Jeang, K.T. Viral and cellular RNA helicases as antiviral targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005, 4, 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuritzkes, D.R. Drug resistance in HIV-1. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2011, 1, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Lerma, J.G.; Nidtha, S.; Blumoff, K.; Weinstock, H.; Heneine, W. Increased ability for selection of zidovudine resistance in a distinct class of wild-type HIV-1 from drug-naive persons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 13907–13912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, S.H.; Scheding, S.; Voliotis, D.; Rasokat, H.; Diehl, V.; Schrappe, M. Side effects of AZT prophylaxis after occupational exposure to HIV-infected blood. Ann. Hematol. 1994, 69, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuehl, A.K.; Noormohamed, S.E. Recombinant erythropoietin for zidovudine-induced anemia in AIDS. Ann. Pharmacother. 1995, 29, 778–779. [Google Scholar]

- Rachlis, A.; Fanning, M.M. Zidovudine toxicity. Clinical features and management. Drug Saf. 1993, 8, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellington, A.D.; Szostak, J.W. In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature 1990, 346, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuerk, C.; MacDougal-Waugh, S. In vitro evolution of functional nucleic acids: High-affinity RNA ligands of HIV-1 proteins. Gene 1993, 137, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, L.I.; Flenker, K.S.; Hernandez, F.J.; Klingelhutz, A.J.; McNamara, J.O.; Giangrande, P.H. Methods for evaluating cell-specific, cell-internalizing RNA aptamers. Pharmaceuticals 2013, 6, 295–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Piotr, S.; Rossi, J. Development of cell-type specific anti-HIV gp120 aptamers for siRNA delivery. J. Vis. Exp. 2011, 52, 357–368. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; You, M.; Pu, Y.; Liu, H.; Ye, M.; Tan, W. Recent developments in protein and cell-targeted aptamer selection and applications. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011, 18, 4117–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, J.O., 2nd; Andrechek, E.R.; Wang, Y.; Viles, K.D.; Rempel, R.E.; Gilboa, E.; Sullenger, B.A.; Giangrande, P.H. Cell type-specific delivery of siRNAs with aptamer-siRNA chimeras. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 1005–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Rossi, J.J. Aptamer-targeted RNAi for HIV-1 therapy. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 721, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Rossi, J.J. Aptamer-targeted cell-specific RNA interference. Silence 2010, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, W.O.; Shum, K.T.; Tanner, J.A. G-quadruplex DNA aptamers and their ligands: Structure, function and application. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2012, 18, 2014–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimjee, S.M.; Rusconi, C.P.; Sullenger, B.A. Aptamers: An emerging class of therapeutics. Annu. Rev. Med. 2005, 56, 555–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E.W.; Shima, D.T.; Calias, P.; Cunningham, E.T., Jr.; Guyer, D.R.; Adamis, A.P. Pegaptanib, a targeted anti-VEGF aptamer for ocular vascular disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006, 5, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doggrell, S.A. Pegaptanib: The first antiangiogenic agent approved for neovascular macular degeneration. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2005, 6, 1421–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, P.; Kurniawan, H.; Byrne, M.E.; Wower, J. Therapeutic RNA aptamers in clinical trials. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 48, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, J.C.; Rossi, J.J. RNA-based therapeutics: Current progress and future prospects. Chem. Biol. 2012, 19, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongelard, F.; Bouvet, P. AS-1411, a guanosine-rich oligonucleotide aptamer targeting nucleolin for the potential treatment of cancer, including acute myeloid leukemia. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 2010, 12, 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, J.C.; DeFeo-Fraulini, T.; Hutabarat, R.M.; Horvath, C.J.; Merlino, P.G.; Marsh, H.N.; Healy, J.M.; Boufakhreddine, S.; Holohan, T.V.; Schaub, R.G. First-in-human evaluation of anti von Willebrand factor therapeutic aptamer ARC1779 in healthy volunteers. Circulation 2007, 116, 2678–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinores, S.A. Pegaptanib in the treatment of wet, age-related macular degeneration. Int. J. Nanomed. 2006, 1, 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Rossi, J.J. Therapeutic potential of aptamer-siRNA conjugates for treatment of HIV-1. BioDrugs 2012, 26, 393–400. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Rossi, J.J. Progress in RNAi-based antiviral therapeutics. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 721, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Rossi, J.J. Cell-specific aptamer-mediated targeted drug delivery. Oligonucleotides 2011, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Rossi, J.J. Bivalent aptamers deliver the punch. Chem. Biol. 2008, 15, 644–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwar, J.R.; Roy, K.; Kanwar, R.K. Chimeric aptamers in cancer cell-targeted drug delivery. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2011, 46, 459–477. [Google Scholar]

- Khati, M. The future of aptamers in medicine. J. Clin. Pathol. 2010, 63, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Y.W.; Kwok, J.; Law, A.W.; Watt, R.M.; Kotaka, M.; Tanner, J.A. Structural basis for discriminatory recognition of Plasmodium lactate dehydrogenase by a DNA aptamer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 15967–15972. [Google Scholar]

- Bunka, D.H.; Stockley, P.G. Aptamers come of age—at last. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006, 4, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuerk, C.; MacDougal, S.; Gold, L. RNA pseudoknots that inhibit human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 6988–6992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, J.; Restle, T.; Steitz, T.A. The structure of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase complexed with an RNA pseudoknot inhibitor. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 4535–4542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P. The emerging field of RNA nanotechnology. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010, 5, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Haque, F.; Hallahan, B.; Reif, R.; Li, H. Uniqueness, advantages, challenges, solutions, and perspectives in therapeutics applying RNA nanotechnology. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2012, 22, 226–245. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, G.C.; Haque, F.; Tor, Y.; Wilhelmsson, L.M.; Toulme, J.J.; Isambert, H.; Guo, P.; Rossi, J.J.; Tenenbaum, S.A.; Shapiro, B.A. A boost for the emerging field of RNA nanotechnology. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 3405–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarapore, P.; Shu, Y.; Guo, P.; Ho, S.M. Application of phi29 motor pRNA for targeted therapeutic delivery of siRNA silencing metallothionein-IIA and survivin in ovarian cancers. Mol. Ther. 2011, 19, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Cinier, M.; Shu, D.; Guo, P. Assembly of multifunctional phi29 pRNA nanoparticles for specific delivery of siRNA and other therapeutics to targeted cells. Methods 2011, 54, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Haque, F.; Shu, D.; Li, W.; Zhu, Z.; Kotb, M.; Lyubchenko, Y.; Guo, P. Fabrication of 14 different RNA nanoparticles for specific tumor targeting without accumulation in normal organs. RNA 2013, 19, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, C.P.; Zhou, J.; Remling, L.; Kuruvilla, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Smith, D.D.; Swiderski, P.; Rossi, J.J.; Akkina, R. An aptamer-siRNA chimera suppresses HIV-1 viral loads and protects from helper CD4(+) T cell decline in humanized mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Banda, N.; Lee, N.S.; Rossi, J.; Akkina, R. RNA-based anti-HIV-1 gene therapeutic constructs in SCID-hu mouse model. Mol. Ther. 2002, 6, 770–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, K.M.; Xiao, Y.; Soh, H.T. Selection is more intelligent than design: Improving the affinity of a bivalent ligand through directed evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 11777–11783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Hu, J.; Peng, M.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Zhao, X.; Tan, W. Generating aptamers by cell-SELEX for applications in molecular medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 3341–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, P.; Kim, S.; Lee, D.K. Nucleic acid aptamers targeting cell-surface proteins. Methods 2011, 54, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Parekh, P.; Turner, P.; Moyer, R.W.; Tan, W. Generating aptamers for recognition of virus-infected cells. Clin. Chem. 2009, 55, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richman, D.D.; Margolis, D.M.; Delaney, M.; Greene, W.C.; Hazuda, D.; Pomerantz, R.J. The challenge of finding a cure for HIV infection. Science 2009, 323, 1304–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.J.; Fisher, T.S.; Prasad, V.R. Anti-HIV inhibitors based on nucleic acids: Emergence of aptamers as potent antivirals. Curr. Drug Targets Infect. Disord. 2003, 3, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, L.; Rossi, J.J.; Weinberg, M.S. Progress and prospects: RNA-based therapies for treatment of HIV infection. Gene Ther. 2007, 14, 1057–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, D.M.; Kissel, J.D.; Patterson, J.T.; Nickens, D.G.; Burke, D.H. HIV-1 inactivation by nucleic acid aptamers. Front. Biosci. 2006, 11, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, J.; Pata, J.D. Getting a grip: Polymerases and their substrate complexes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1999, 9, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, E. Chemotherapeutic approaches to the treatment of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). J. Med. Chem. 1986, 29, 1561–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, E. Perspectives of non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) in the therapy of HIV-1 infection. Farmaco 1999, 54, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kensch, O.; Connolly, B.A.; Steinhoff, H.J.; McGregor, A.; Goody, R.S.; Restle, T. HIV-1 reverse transcriptase-pseudoknot RNA aptamer interaction has a binding affinity in the low picomolar range coupled with high specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 18271–18278. [Google Scholar]

- Chaloin, L.; Lehmann, M.J.; Sczakiel, G.; Restle, T. Endogenous expression of a high-affinity pseudoknot RNA aptamer suppresses replication of HIV-1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 4001–4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wang, Y.; Pothukuchy, A.; Syrett, A.; Husain, N.; Gopalakrisha, S.; Kosaraju, P.; Ellington, A.D. Aptamers that recognize drug-resistant HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 6739–6751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreola, M.L.; Pileur, F.; Calmels, C.; Ventura, M.; Tarrago-Litvak, L.; Toulme, J.J.; Litvak, S. DNA aptamers selected against the HIV-1 RNase H display in vitro antiviral activity. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 10087–10094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasunderam, A.; Ferguson, M.R.; Rojo, D.R.; Thiviyanathan, V.; Li, X.; O’Brien, W.A.; Gorenstein, D.G. Combinatorial selection, inhibition, and antiviral activity of DNA thioaptamers targeting the RNase H domain of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 10388–10395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeStefano, J.J.; Nair, G.R. Novel aptamer inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase. Oligonucleotides 2008, 18, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, D.J.; Feigon, J.; Hostomsky, Z.; Gold, L. High-affinity ssDNA inhibitors of the reverse transcriptase of type 1 human immunodeficiency virus. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 9599–9610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissel, J.D.; Held, D.M.; Hardy, R.W.; Burke, D.H. Single-stranded DNA aptamer RT1t49 inhibits RT polymerase and RNase H functions of HIV type 1, HIV type 2, and SIVCPZ RTs. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2007, 23, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.T.; DeStefano, J.J. DNA aptamers to human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase selected by a primer-free SELEX method: Characterization and comparison with other aptamers. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2012, 22, 162–176. [Google Scholar]

- Whatley, A.S.; Ditzler, M.A.; Lange, M.J.; Biondi, E.; Sawyer, A.W.; Chang, J.L.; Franken, J.D.; Burke, D.H. Potent Inhibition of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase and Replication by Nonpseudoknot, “UCAA-motif” RNA Aptamers. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2013, 2, e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditzler, M.A.; Lange, M.J.; Bose, D.; Bottoms, C.A.; Virkler, K.F.; Sawyer, A.W.; Whatley, A.S.; Spollen, W.; Givan, S.A.; Burke, D.H. High-throughput sequence analysis reveals structural diversity and improved potency among RNA inhibitors of HIV reverse transcriptase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 1873–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Soultrait, V.R.; Lozach, P.Y.; Altmeyer, R.; Tarrago-Litvak, L.; Litvak, S.; Andreola, M.L. DNA aptamers derived from HIV-1 RNase H inhibitors are strong anti-integrase agents. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 324, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure-Perraud, A.; Metifiot, M.; Reigadas, S.; Recordon-Pinson, P.; Parissi, V.; Ventura, M.; Andreola, M.L. The guanine-quadruplex aptamer 93del inhibits HIV-1 replication ex vivo by interfering with viral entry, reverse transcription and integration. Antivir. Ther. 2011, 16, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, N.; Hogan, M.E. Structure-activity of tetrad-forming oligonucleotides as a potent anti-HIV therapeutic drug. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 34992–34999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, D.; Duclair, S.; Datta, S.A.; Ellington, A.; Rein, A.; Prasad, V.R. RNA aptamers directed to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag polyprotein bind to the matrix and nucleocapsid domains and inhibit virus production. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Kim, M.Y.; Lee, J.H.; You, J.C.; Jeong, S. Selection and stabilization of the RNA aptamers against the human immunodeficiency virus type-1 nucleocapsid protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 291, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.Y.; Jeong, S. RNA aptamers that bind the nucleocapsid protein contain pseudoknots. Mol. Cells 2003, 16, 413–417. [Google Scholar]

- Sayer, N.; Ibrahim, J.; Turner, K.; Tahiri-Alaoui, A.; James, W. Structural characterization of a 2'F-RNA aptamer that binds a HIV-1 SU glycoprotein, gp120. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 293, 924–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mufhandu, H.T.; Gray, E.S.; Madiga, M.C.; Tumba, N.; Alexandre, K.B.; Khoza, T.; Wibmer, C.K.; Moore, P.L.; Morris, L.; Khati, M. UCLA1, a synthetic derivative of a gp120 RNA aptamer, inhibits entry of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 4989–4999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Neff, C.P.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Smith, D.D.; Swiderski, P.; Aboellail, T.; Huang, Y.; Du, Q.; et al. Systemic administration of combinatorial dsiRNAs via nanoparticles efficiently suppresses HIV-1 infection in humanized mice. Mol. Ther. 2011, 19, 2228–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Swiderski, P.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Neff, C.P.; Akkina, R.; Rossi, J.J. Selection, characterization and application of new RNA HIV gp 120 aptamers for facile delivery of Dicer substrate siRNAs into HIV infected cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 3094–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, R.; Katahira, M.; Nishikawa, S.; Baba, T.; Taira, K.; Kumar, P.K. A novel RNA motif that binds efficiently and specifically to the Ttat protein of HIV and inhibits the trans-activation by Tat of transcription in vitro and in vivo. Genes Cells 2000, 5, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.B.; Green, L.; MacDougal-Waugh, S.; Tuerk, C. Characterization of an in vitro-selected RNA ligand to the HIV-1 Rev protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1994, 235, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiziau, C.; Dausse, E.; Yurchenko, L.; Toulme, J.J. DNA aptamers selected against the HIV-1 trans-activation-responsive RNA element form RNA-DNA kissing complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 12730–12737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duconge, F.; Toulme, J.J. In vitro selection identifies key determinants for loop-loop interactions: RNA aptamers selective for the TAR RNA element of HIV-1. RNA 1999, 5, 1605–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watrin, M.; von Pelchrzim, F.; Dausse, E.; Schroeder, R.; Toulme, J.J. In vitro selection of RNA aptamers derived from a genomic human library against the TAR RNA element of HIV-1. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 6278–6284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekkai, D.; Dausse, E.; di Primo, C.; Darfeuille, F.; Boiziau, C.; Toulme, J.J. In vitro selection of DNA aptamers against the HIV-1 TAR RNA hairpin. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 2002, 12, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.K.; Machida, K.; Urvil, P.T.; Kakiuchi, N.; Vishnuvardhan, D.; Shimotohno, K.; Taira, K.; Nishikawa, S. Isolation of RNA aptamers specific to the NS3 protein of hepatitis C virus from a pool of completely random RNA. Virology 1997, 237, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, K.; Vishnuvardhan, D.; Sekiya, S.; Hwang, J.; Kakiuchi, N.; Taira, K.; Shimotohno, K.; Kumar, P.K.; Nishikawa, S. Isolation and characterization of RNA aptamers specific for the hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 3 protease. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000, 267, 3685–3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, F.; Funaji, K.; Fukuda, K.; Nishikawa, S. In vitro selection of RNA aptamers against the HCV NS3 helicase domain. Oligonucleotides 2004, 14, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biroccio, A.; Hamm, J.; Incitti, I.; de Francesco, R.; Tomei, L. Selection of RNA aptamers that are specific and high-affinity ligands of the hepatitis C virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 3688–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellecave, P.; Cazenave, C.; Rumi, J.; Staedel, C.; Cosnefroy, O.; Andreola, M.L.; Ventura, M.; Tarrago-Litvak, L.; Astier-Gin, T. Inhibition of hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA polymerase by DNA aptamers: Mechanism of inhibition of in vitro RNA synthesis and effect on HCV-infected cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 2097–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, J.H.; Lim, J.H.; Kim, J.H.; Han, W.; Lee, S.H.; Noh, G.J.; Lee, S.W. Inhibition of hepatitis C virus (HCV) replication by specific RNA aptamers against HCV NS5B RNA replicase. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 7064–7074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marton, S.; Romero-Lopez, C.; Berzal-Herranz, A. RNA aptamer-mediated interference of HCV replication by targeting the CRE-5BSL3.2 domain. J. Viral Hepat. 2013, 20, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, K.; Umehara, T.; Fukuda, K.; Hwang, J.; Kuno, A.; Hasegawa, T.; Nishikawa, S. RNA aptamers targeted to domain II of hepatitis C virus IRES that bind to its apical loop region. J. Biochem. 2003, 133, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, K.; Umehara, T.; Fukuda, K.; Kuno, A.; Hasegawa, T.; Nishikawa, S. A hepatitis C virus (HCV) internal ribosome entry site (IRES) domain III-IV-targeted aptamer inhibits translation by binding to an apical loop of domain IIId. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Lopez, C.; Barroso-delJesus, A.; Puerta-Fernandez, E.; Berzal-Herranz, A. Interfering with hepatitis C virus IRES activity using RNA molecules identified by a novel in vitro selection method. Biol. Chem. 2005, 386, 183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Lopez, C.; Diaz-Gonzalez, R.; Barroso-delJesus, A.; Berzal-Herranz, A. Inhibition of hepatitis C virus replication and internal ribosome entry site-dependent translation by an RNA molecule. J. Gen. Virol. 2009, 90, 1659–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Hu, B.; Ma, Z.Y.; Huang, H.P.; Yu, Y.; Liu, S.P.; Lu, M.J.; Yang, D.L. Development of HBsAg-binding aptamers that bind HepG2.2.15 cells via HBV surface antigen. Virol. Sin. 2010, 25, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Beck, J.; Nassal, M.; Hu, K.H. A SELEX-screened aptamer of human hepatitis B virus RNA encapsidation signal suppresses viral replication. PLoS One 2011, 6, e27862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shum, K.T.; Tanner, J.A. Differential inhibitory activities and stabilisation of DNA aptamers against the SARS coronavirus helicase. ChemBioChem 2008, 9, 3037–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, K.J.; Lee, N.R.; Yeo, W.S.; Jeong, Y.J.; Kim, D.E. Isolation of inhibitory RNA aptamers against severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus NTPase/Helicase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 366, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.H.; Kayhan, B.; Ben-Yedidia, T.; Arnon, R. A DNA aptamer prevents influenza infection by blocking the receptor binding region of the viral hemagglutinin. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 48410–48419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Dong, J.; Yao, L.; Chen, A.; Jia, R.; Huan, L.; Guo, J.; Shu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Potent inhibition of human influenza H5N1 virus by oligonucleotides derived by SELEX. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 366, 670–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, S.C.; Misono, T.S.; Kawasaki, K.; Mizuno, T.; Imai, M.; Odagiri, T.; Kumar, P.K. An RNA aptamer that distinguishes between closely related human influenza viruses and inhibits haemagglutinin-mediated membrane fusion. J. Gen. Virol. 2006, 87, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misono, T.S.; Kumar, P.K. Selection of RNA aptamers against human influenza virus hemagglutinin using surface plasmon resonance. Anal. Biochem. 2005, 342, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongphatcharachai, M.; Wang, P.; Enomoto, S.; Webby, R.J.; Gramer, M.R.; Amonsin, A.; Sreevatsan, S. Neutralizing DNA aptamers against swine influenza H3N2 viruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.K.; Lee, C.; Lee, K.S.; Choe, S.Y.; Mo, I.P.; Seong, R.H.; Hong, S.; Jeon, S.H. DNA aptamers against the receptor binding region of hemagglutinin prevent avian influenza viral infection. Mol. Cells 2011, 32, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Kim, S.; Yoon, H.; Kim, K.B.; Kalme, S.S.; Oh, S.; Song, C.S.; Kim, D.E. Selection of an antiviral RNA aptamer against hemagglutinin of the subtype H5 avian influenza virus. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2011, 21, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, S.C.; Sakamaki, Y.; Kawasaki, K.; Kumar, P.K. An efficient RNA aptamer against human influenza B virus hemagglutinin. J. Biochem. 2006, 139, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.R.; Hu, G.Q.; Zhang, T.; Yang, Y.J.; Zhao, L.L.; Qi, Y.L.; Wang, H.L.; Gao, Y.W.; Yang, S.T.; Xia, X.Z. Isolation of ssDNA aptamers that inhibit rabies virus. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2012, 14, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.R.; Liu, Q.; Zheng, X.X.; Gai, W.W.; Xue, X.H.; Hu, G.Q.; Wu, H.X.; Wang, H.L.; Yang, S.T.; Xia, X.Z. Aptamers targeting rabies virus-infected cells inhibit viral replication both in vitro and in vivo. Virus Res. 2013, 173, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano-Garibay, J.D.; Benitez-Hess, M.L.; Alvarez-Salas, L.M. Isolation and characterization of an RNA aptamer for the HPV-16 E7 oncoprotein. Arch. Med. Res. 2011, 42, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.C.; Zarbl, H. Use of cell-SELEX to generate DNA aptamers as molecular probes of HPV-associated cervical cancer cells. PLoS One 2012, 7, e36103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, C.; Cesur, O.; Forrest, S.; Belyaeva, T.A.; Bunka, D.H.; Blair, G.E.; Stonehouse, N.J. An RNA aptamer provides a novel approach for the induction of apoptosis by targeting the HPV16 E7 oncoprotein. PLoS One 2013, 8, e64781. [Google Scholar]

- Nicol, C.; Bunka, D.H.; Blair, G.E.; Stonehouse, N.J. Effects of single nucleotide changes on the binding and activity of RNA aptamers to human papillomavirus 16 E7 oncoprotein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 405, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, S.C.; Hayashi, K.; Kumar, P.K. Aptamer that binds to the gD protein of herpes simplex virus 1 and efficiently inhibits viral entry. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 6732–6744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.D.; Bunka, D.H.; Forzan, M.; Spear, P.G.; Stockley, P.G.; McGowan, I.; James, W. Generation of neutralizing aptamers against herpes simplex virus type 2: Potential components of multivalent microbicides. J. Gen. Virol. 2011, 92, 1493–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickens, D.G.; Patterson, J.T.; Burke, D.H. Inhibition of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase by RNA aptamers in Escherichia coli. RNA 2003, 9, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.; Prasad, V.R. Potent inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by template analog reverse transcriptase inhibitors derived by SELEX (systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment). J. Virol. 2002, 76, 6545–6557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, M.J.; Sharma, T.K.; Whatley, A.S.; Landon, L.A.; Tempesta, M.A.; Johnson, M.C.; Burke, D.H. Robust suppression of HIV replication by intracellularly expressed reverse transcriptase aptamers is independent of ribozyme processing. Mol. Ther. 2012, 20, 2304–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante-Appiah, E.; Skalka, A.M. Molecular mechanisms in retrovirus DNA integration. Antiviral Res. 1997, 36, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Shi, L.; Wang, E.; Dong, S. Multifunctional G-quadruplex aptamers and their application to protein detection. Chemistry 2009, 15, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, A.T.; Kuryavyi, V.; Ma, J.B.; Faure, A.; Andreola, M.L.; Patel, D.J. An interlocked dimeric parallel-stranded DNA quadruplex: A potent inhibitor of HIV-1 integrase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 634–639. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, S.H.; Chin, K.H.; Wang, A.H. DNA aptamers as potential anti-HIV agents. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005, 30, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, A.; Neamati, N.; Ojwang, J.O.; Sunder, S.; Rando, R.F.; Pommier, Y. Inhibition of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase by guanosine quartet structures. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 13762–13771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magbanua, E.; Zivkovic, T.; Hansen, B.; Beschorner, N.; Meyer, C.; Lorenzen, I.; Grotzinger, J.; Hauber, J.; Torda, A.E.; Mayer, G.; et al. d(GGGT) 4 and r(GGGU) 4 are both HIV-1 inhibitors and interleukin-6 receptor aptamers. RNA Biol. 2013, 10, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheysen, D.; Jacobs, E.; de Foresta, F.; Thiriart, C.; Francotte, M.; Thines, D.; de Wilde, M. Assembly and release of HIV-1 precursor Pr55gag virus-like particles from recombinant baculovirus-infected insect cells. Cell 1989, 59, 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Wills, J.W.; Craven, R.C. Form, function, and use of retroviral gag proteins. AIDS 1991, 5, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirov, D.G.; Freed, E.O. Retrovirus budding. Virus Res. 2004, 106, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rein, A.; Henderson, L.E.; Levin, J.G. Nucleic-acid-chaperone activity of retroviral nucleocapsid proteins: Significance for viral replication. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1998, 23, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Guzman, R.N.; Wu, Z.R.; Stalling, C.C.; Pappalardo, L.; Borer, P.N.; Summers, M.F. Structure of the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein bound to the SL3 psi-RNA recognition element. Science 1998, 279, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.Y.; Jeong, S. Inhibition of the functions of the nucleocapsid protein of human immunodeficiency virus-1 by an RNA aptamer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 320, 1181–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, P.D.; Wyatt, R.; Robinson, J.; Sweet, R.W.; Sodroski, J.; Hendrickson, W.A. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature 1998, 393, 648–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattentau, Q.J.; Moore, J.P. The role of CD4 in HIV binding and entry. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1993, 342, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugolini, S.; Mondor, I.; Sattentau, Q.J. HIV-1 attachment: Another look. Trends Microbiol. 1999, 7, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khati, M.; Schuman, M.; Ibrahim, J.; Sattentau, Q.; Gordon, S.; James, W. Neutralization of infectivity of diverse R5 clinical isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by gp120-binding 2'F-RNA aptamers. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 12692–12698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.K.; Griffiths, C.; Lea, S.M.; James, W. Structural characterization of an anti-gp120 RNA aptamer that neutralizes R5 strains of HIV-1. RNA 2005, 11, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.K.; Khati, M.; Tang, M.; Wyatt, R.; Lea, S.M.; James, W. An aptamer that neutralizes R5 strains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 blocks gp120-CCR5 interaction. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 13806–13810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, C.; Forzan, M.; Sproat, B.; Pantophlet, R.; McGowan, I.; Burton, D.; James, W. An aptamer that neutralizes R5 strains of HIV-1 binds to core residues of gp120 in the CCR5 binding site. Virology 2008, 381, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, H.; Li, S.; Zaia, J.; Rossi, J.J. Novel dual inhibitory function aptamer-siRNA delivery system for HIV-1 therapy. Mol. Ther. 2008, 16, 1481–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Neff, C.P.; Swiderski, P.; Li, H.; Smith, D.D.; Aboellail, T.; Remling-Mulder, L.; Akkina, R.; Rossi, J.J. Functional in vivo delivery of multiplexed anti-HIV-1 siRNAs via a chemically synthesized aptamer with a sticky bridge. Mol. Ther. 2013, 21, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.K.; Guo, C.; Josephs, S.F.; Wong-Staal, F. Trans-activator gene of human T-lymphotropic virus type III (HTLV-III). Science 1985, 229, 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Berkhout, B.; Silverman, R.H.; Jeang, K.T. Tat trans-activates the human immunodeficiency virus through a nascent RNA target. Cell 1989, 59, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensoli, B.; Barillari, G.; Salahuddin, S.Z.; Gallo, R.C.; Wong-Staal, F. Tat protein of HIV-1 stimulates growth of cells derived from Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions of AIDS patients. Nature 1990, 345, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, B.R.; Greene, W.C. Regulatory pathways governing HIV-1 replication. Cell 1989, 58, 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, C.A.; Pavlakis, G.N. Tat and Rev: Positive regulators of HIV gene expression. AIDS 1990, 4, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjems, J.; Frankel, A.D.; Sharp, P.A. Specific regulation of mRNA splicing in vitro by a peptide from HIV-1 Rev. Cell 1991, 67, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konopka, K.; Lee, N.S.; Rossi, J.; Duzgunes, N. Rev-binding aptamer and CMV promoter act as decoys to inhibit HIV replication. Gene 2000, 255, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gait, M.J.; Karn, J. RNA recognition by the human immunodeficiency virus Tat and Rev proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1993, 18, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatignol, A.; Duarte, M.; Daviet, L.; Chang, Y.N.; Jeang, K.T. Sequential steps in Tat trans-activation of HIV-1 mediated through cellular DNA, RNA, and protein binding factors. Gene Expr. 1996, 5, 217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, B.; Bilusic, I.; Lorenz, C.; Schroeder, R. Genomic SELEX: A discovery tool for genomic aptamers. Methods 2010, 52, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Rossi, J.J. Lentiviral vector delivery of siRNA and shRNA encoding genes into cultured and primary hematopoietic cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2005, 309, 261–272. [Google Scholar]

- DiGiusto, D.L.; Krishnan, A.; Li, L.; Li, H.; Li, S.; Rao, A.; Mi, S.; Yam, P.; Stinson, S.; Kalos, M.; et al. RNA-based gene therapy for HIV with lentiviral vector-modified CD34(+) cells in patients undergoing transplantation for AIDS-related lymphoma. Sci. Transl. Med. 2010, 2, 36–ra43. [Google Scholar]

- Wasley, A.; Alter, M.J. Epidemiology of hepatitis C: Geographic differences and temporal trends. Semin. Liver Dis. 2000, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanazaki, K. Antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis B: A review. Curr. Drug Targets Inflamm. Allergy 2004, 3, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, N. Genome of human hepatitis C virus (HCV): Gene organization, sequence diversity, and variation. Microb. Comp. Genomics 2000, 5, 129–151. [Google Scholar]

- Failla, C.; Tomei, L.; de Francesco, R. Both NS3 and NS4A are required for proteolytic processing of hepatitis C virus nonstructural proteins. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 3753–3760. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.W.; Gwack, Y.; Han, J.H.; Choe, J. C-terminal domain of the hepatitis C virus NS3 protein contains an RNA helicase activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 215, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, F.; Kakiuchi, N.; Funaji, K.; Fukuda, K.; Sekiya, S.; Nishikawa, S. Inhibition of HCV NS3 protease by RNA aptamers in cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 1935–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, K.; Umehara, T.; Sekiya, S.; Kunio, K.; Hasegawa, T.; Nishikawa, S. An RNA ligand inhibits hepatitis C virus NS3 protease and helicase activities. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 325, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umehara, T.; Fukuda, K.; Nishikawa, F.; Kohara, M.; Hasegawa, T.; Nishikawa, S. Rational design of dual-functional aptamers that inhibit the protease and helicase activities of HCV NS3. J. Biochem. 2005, 137, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, J.; Sharma, P.K.; Sharma, A. A review on an update of NS5B polymerase hepatitis C virus inhibitors. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2012, 16, 667–671. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukiyama-Kohara, K.; Iizuka, N.; Kohara, M.; Nomoto, A. Internal ribosome entry site within hepatitis C virus RNA. J. Virol. 1992, 66, 1476–1483. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego, J.; Varani, G. The hepatitis C virus internal ribosome-entry site: A new target for antiviral research. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2002, 30, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, K.; Umehara, T.; Nishikawa, F.; Fukuda, K.; Hasegawa, T.; Nishikawa, S. Increased inhibitory ability of conjugated RNA aptamers against the HCV IRES. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 386, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cheng, G.; Mahato, R.I. RNAi for treating hepatitis B viral infection. Pharm. Res. 2008, 25, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoulim, F. Hepatitis B virus resistance to antiviral drugs: Where are we going? Liver Int. 2011, 31, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeger, C.; Mason, W.S. Hepatitis B virus biology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000, 64, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, J.; Mason, W.S. Replication of the genome of a hepatitis B-like virus by reverse transcription of an RNA intermediate. Cell 1982, 29, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.H.; Seeger, C. The reverse transcriptase of hepatitis B virus acts as a protein primer for viral DNA synthesis. Cell 1992, 71, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, R.C.; Lavine, J.E.; Chang, L.J.; Varmus, H.E.; Ganem, D. Polymerase gene products of hepatitis B viruses are required for genomic RNA packaging as wel as for reverse transcription. Nature 1990, 344, 552–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flodell, S.; Petersen, M.; Girard, F.; Zdunek, J.; Kidd-Ljunggren, K.; Schleucher, J.; Wijmenga, S. Solution structure of the apical stem-loop of the human hepatitis B virus encapsidation signal. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, 4449–4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiris, J.S.; Lai, S.T.; Poon, L.L.; Guan, Y.; Yam, L.Y.; Lim, W.; Nicholls, J.; Yee, W.K.; Yan, W.W.; Cheung, M.T.; et al. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 2003, 361, 1319–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, K.; Masignani, V.; Eickmann, M.; Becker, S.; Abrignani, S.; Klenk, H.D.; Rappuoli, R. SARS—beginning to understand a new virus. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2003, 1, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, J.A.; Watt, R.M.; Chai, Y.B.; Lu, L.Y.; Lin, M.C.; Peiris, J.S.; Poon, L.L.; Kung, H.F.; Huang, J.D. The severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus NTPase/helicase belongs to a distinct class of 5' to 3' viral helicases. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 39578–39582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, A.M.; van Boheemen, S.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Osterhaus, A.D.; Fouchier, R.A. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1814–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Boheemen, S.; de Graaf, M.; Lauber, C.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Raj, V.S.; Zaki, A.M.; Osterhaus, A.D.; Haagmans, B.L.; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Snijder, E.J.; et al. Genomic characterization of a newly discovered coronavirus associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome in humans. mBio 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josset, L.; Menachery, V.D.; Gralinski, L.E.; Agnihothram, S.; Sova, P.; Carter, V.S.; Yount, B.L.; Graham, R.L.; Baric, R.S.; Katze, M.G. Cell host response to infection with novel human coronavirus EMC predicts potential antivirals and important differences with SARS coronavirus. mBio 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elderfield, R.; Barclay, W. Influenza pandemics. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2011, 719, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, R.G. 1918 Spanish influenza: The secrets remain elusive. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 1164–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, T.; Zhou, J.; Shu, Y. Serologic study for influenza A (H7N9) among high-risk groups in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 2339–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Ibrahim, M.S.; Suzuki, Y.; Ikuta, K. The changing nature of avian influenza A virus (H5N1). Trends Microbiol. 2012, 20, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultyaev, A.P.; Fouchier, R.A.; Olsthoorn, R.C. Influenza virus RNA structure: Unique and common features. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 29, 533–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saladino, R.; Barontini, M.; Crucianelli, M.; Nencioni, L.; Sgarbanti, R.; Palamara, A.T. Current advances in anti-influenza therapy. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010, 17, 2101–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stropkovska, A.; Janulikova, J.; Vareckova, E. Trends in development of the influenza vaccine with broader cross-protection. Acta Virol. 2010, 54, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, D.R.; Poignard, P.; Stanfield, R.L.; Wilson, I.A. Broadly neutralizing antibodies present new prospects to counter highly antigenically diverse viruses. Science 2012, 337, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skehel, J.J.; Wiley, D.C. Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: The influenza hemagglutinin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000, 69, 531–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, K.G.; Wood, J.M.; Zambon, M. Influenza. Lancet 2003, 362, 1733–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, M.Z.; Qasim, M.; Zia, S.; Khan, M.; Ashfaq, U.A.; Khan, S. Rabies molecular virology, diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Virol. J. 2012, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietzschold, B.; Schnell, M.; Koprowski, H. Pathogenesis of rabies. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2005, 292, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, M. Pathology and epidemiology of HPV infection in females. Gynecol. Oncol. 2010, 117, S5–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin-Drubin, M.E.; Meyers, J.; Munger, K. Cancer associated human papillomaviruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012, 2, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczynski, S.P.; Bergen, S.; Walker, J.; Liao, S.Y.; Pearlman, L.F. Human papillomaviruses and cervical cancer: Analysis of histopathologic features associated with different viral types. Hum. Pathol. 1988, 19, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Narayan, N.; Pim, D.; Tomaic, V.; Massimi, P.; Nagasaka, K.; Kranjec, C.; Gammoh, N.; Banks, L. Human papillomaviruses, cervical cancer and cell polarity. Oncogene 2008, 27, 7018–7030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaio, D.; Liao, J.B. Human papillomaviruses and cervical cancer. Adv. Virus Res. 2006, 66, 125–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mineta, H.; Ogino, T.; Amano, H.M.; Ohkawa, Y.; Araki, K.; Takebayashi, S.; Miura, K. Human papilloma virus (HPV) type 16 and 18 detected in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 1998, 18, 4765–4768. [Google Scholar]

- Schiller, J.T.; Lowy, D.R. Understanding and learning from the success of prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccines. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghittoni, R.; Accardi, R.; Hasan, U.; Gheit, T.; Sylla, B.; Tommasino, M. The biological properties of E6 and E7 oncoproteins from human papillomaviruses. Virus Genes 2010, 40, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauenburg, S.; Zwerschke, W.; Jansen-Durr, P. Induction of apoptosis in cervical carcinoma cells by peptide aptamers that bind to the HPV-16 E7 oncoprotein. FASEB J. 2001, 15, 592–594. [Google Scholar]

- Finzer, P.; Aguilar-Lemarroy, A.; Rosl, F. The role of human papillomavirus oncoproteins E6 and E7 in apoptosis. Cancer Lett. 2002, 188, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, E.; Cabrejos, M.E.; Banks, L.; Allende, J.E. Human papillomavirus-16 E7 protein inhibits the DNA interaction of the TATA binding transcription factor. J. Cell. Biochem. 2002, 85, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernat, A.; Avvakumov, N.; Mymryk, J.S.; Banks, L. Interaction between the HPV E7 oncoprotein and the transcriptional coactivator p300. Oncogene 2003, 22, 7871–7881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, K.G.; Frink, R.J.; Devi, G.B.; Swain, M.; Galloway, D.; Wagner, E.K. Herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 homology in the region between 0.58 and 0.68 map units. J. Virol. 1984, 52, 615–623. [Google Scholar]

- Rozenberg, F.; Deback, C.; Agut, H. Herpes simplex encephalitis: From virus to therapy. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets 2011, 11, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reske, A.; Pollara, G.; Krummenacher, C.; Chain, B.M.; Katz, D.R. Understanding HSV-1 entry glycoproteins. Rev. Med. Virol. 2007, 17, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasky, L.A.; Dowbenko, D.J. DNA sequence analysis of the type-common glycoprotein-D genes of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2. DNA 1984, 3, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Shum, K.T.; Burnett, J.C.; Rossi, J.J. Nanoparticle-based delivery of RNAi therapeutics: Progress and challenges. Pharmaceuticals 2013, 6, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, W. Aptamers in the virologists’ toolkit. J. Gen. Virol. 2007, 88, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.D.; Cookson, J.; Coventry, V.K.; Sproat, B.; Rabe, L.; Cranston, R.D.; McGowan, I.; James, W. Protection of HIV neutralizing aptamers against rectal and vaginal nucleases: Implications for RNA-based therapeutics. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 2526–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, L.A.; Vrbanac, V.; Trifonova, R.; Brehm, M.A.; Gilboa-Geffen, A.; Tanno, S.; Greiner, D.L.; Luster, A.D.; Tager, A.M.; Lieberman, J. Durable knockdown and protection from HIV transmission in humanized mice treated with gel-formulated CD4 aptamer-siRNA chimeras. Mol. Ther. 2013, 21, 1378–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).