Buprenorphine Oral Lyophilisate for Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: Pharmacology and Clinical Efficacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Epidemiology and Diagnosis of Opioid Use Disorder

1.2. Neurobiology of Opioid Use Disorder—Brief Update

1.3. Clinical Course of Opioid Use Disorder

1.4. Existing Treatments

1.5. Pharmacotherapy in Opioid Use Disorders

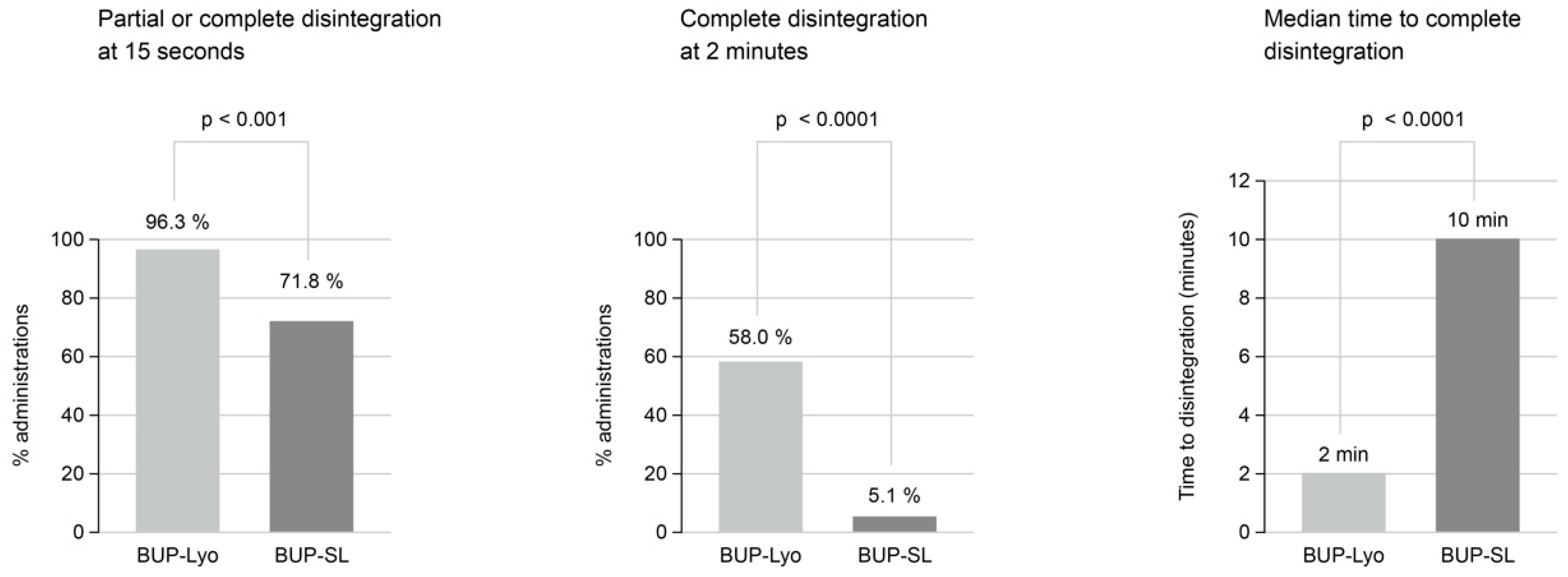

2. Buprenorphine Lyophilisate (Espranor) as a Therapeutic Approach

2.1. Pharmacology

2.1.1. Pharmacokinetics (Regulatory Assessment Report [73])

2.1.2. Clinical Studies

Bioavailability

Dosing and Safety

Pharmacology

Pharmacokinetics

2.1.3. Observational Study by Langridge and Bromley [74]

3. Discussion

4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BUP | Buprenorphine |

| BUP-Lyo | Buprenorphine lyophilisate |

| BUP-SL | Sublingual buprenorphine |

| CBT | Cognitive behavioural therapy |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| Cmax | Peak plasma concentration |

| CYP | Cytochrome P450 |

| DALYs | Disability-adjusted Life Years |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| ICD | International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| MET | Methadone |

| OAT | Opioid agonist treatment |

| OOWS | Objective Opiate Withdrawal Scale |

| OST | Opioid substitution treatment |

| OUD | Opioid use disorder |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SOWS | Subjective Opiate Withdrawal Scale |

References

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Soyka, M. Approved medications for opioid use disorder: Current update. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2025, 26, 1055–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1789–1858.

- Zhang, J.; Liu, R.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Pei, W.; Hou, J.; Li, S. Global burden, socioeconomic disparities, and spatiotemporal dynamics of opioid use disorder mortality and disability: A comprehensive analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017–2021. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degenhardt, L.; Grebely, J.; Stone, J.; Hickman, M.; Vickerman, P.; Marshall, B.D.L.; Bruneau, J.; Altice, F.L.; Henderson, G.; Rahimi-Movaghar, A.; et al. Global patterns of opioid use and dependence: Harms to populations, interventions, and future action. Lancet 2019, 394, 1560–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). World Drug Report 2024; United Nations Publication: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt, L.; Bucello, C.; Mathers, B.; Briegleb, C.; Ali, H.; Hickman, M.; McLaren, J. Mortality among regular or dependent users of heroin and other opioids: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Addiction 2011, 106, 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.; Strang, J. Medication treatment of opioid use disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 87, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crotty, K.; Freedman, K.; Kampman, K. Executive summary of the focused update of the ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder. J. Addict. Med. 2020, 14, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelpietra, G.; Knudsen, A.K.S.; Agardh, E.A.; Armocida, B.; Beghi, M.; Iburg, K.M.; Logroscino, G.; Ma, R.; Starace, F.; Steel, N.; et al. The burden of mental disorders, substance use disorders and self-harm among young people in Europe, 1990–2019: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2022, 16, 100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraudon, I.; Abel-Ollo, K.; Vanaga-Arāja, D.; Heudtlass, P.; Griffiths, P. Nitazenes represent a growing threat to public health in Europe. Lancet Public Health 2024, 9, e216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, R.A.; Aleshire, N.; Zibbell, J.E.; Gladden, R.M. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2000–2014. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2016, 64, 1378–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuchat, A.; Houry, D.; Guy, G.P., Jr. New data on opioid use and prescribing in the United States. JAMA 2017, 318, 425–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wise, J. Nitazenes: Toxicologists warn of rise in overdoses linked to class of synthetic opioids. BMJ 2024, 387, q2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, A.; Gupta, M. Physiology, Opioid Receptor. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538489/ (accessed on 24 July 2023).

- Strang, J.; Volkow, N.D.; Degenhardt, L.; Hickman, M.; Johnson, K.; Koob, G.F.; Marshall, B.D.L.; Tydall, M.; Walsh, S.L. Opioid use disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crist, R.C.; Reiner, B.C.; Berrettini, W.H. A review of opioid addiction genetics. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 27, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer-Pérez, C.; Romero, S.M.; Blanco-Gandía, M.C. Neurobiological theories of addiction: A comprehensive review. Psychoactives 2024, 3, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koob, G.F. Neurobiology of opioid addiction: Opponent process, hyperkatifeia, and negative reinforcement. Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 87, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.O.; Fisher, H.S.; Sullivam, K.A.; Corradin, O.; Sanchez-Roige, S.; Gaddis, N.C.; Sami, Y.N.; Townsend, A.; Teixeira Prates, E.; Pavicic, M.; et al. An emerging multi-omic understanding of the genetics of opioid addiction. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e172886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N.D.; Blanco, C. The changing opioid crisis: Development, challenges and opportunities. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N.D.; Blanco, C. Neurobiologic advances from the brain disease model of addiction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N.D.; Michaelides, M.; Baier, R. The neuroscience of drug reward and addiction. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 2115–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehni, A.K.; Jaggi, A.S.; Singh, N. Opioid withdrawal syndrome: Emerging concepts and novel therapeutic targets. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2013, 12, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hser, Y.I.; Evans, E.; Huang, D.; Weiss, R.; Saxon, A.; Carroll, K.M.; Woody, G.; Liu, D.; Wakim, P.; Matthews, A.G.; et al. Long-term outcomes after randomization to buprenorphine/naloxone versus methadone in a multi-site trial. Addiction 2016, 111, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelty, E.; Hulse, G. Morbidity and mortality in opioid dependent patients after entering an opioid pharmacotherapy compared with a cohort of non-dependent controls. J. Public Health 2018, 40, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larney, S. Does opioid substitution treatment in prisons reduce injecting-related HIV risk behaviours? A systematic review. Addiction 2010, 105, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfund, R.A.; Ginley, M.K.; Boness, C.L.; Rash, C.J.; Zajac, K.; Witkiewitz, K. Management for drug use disorders: Meta-analysis and application of Tolin’s criteria. Clin. Psychol. 2024, 31, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, E.; Mitcheson, L. Psychosocial interventions in opiate substitution treatment services: Does the evidence provide a case for optimism or nihilism? Addiction 2017, 112, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugosh, K.; Abraham, A.; Seymour, B.; McLoyd, K.; Chalk, M.; Festinger, D. A systematic review on the use of psychosocial interventions in conjunction with medications for the treatment of opioid addiction. J. Addict. Med. 2016, 10, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, C.T.; Hammal, F.; Hancock, M.; Bartlett, N.T.; Gladwin, K.K.; Adams, D.; Loverock, A.; Hodgins, D.C. Forty-eight years of research on psychosocial interventions in the treatment of opioid use disorder: A scoping review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021, 218, 108434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, L.A.; Meredith, L.R.; Kiluk, B.D.; Walthers, J.; Carroll, K.M.; Magill, M. Combined pharmacotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with alcohol or substance use disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e208279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, D.D.; Sells, S.B. Opioid Addiction and Treatment: A 12-Year Follow-Up; Robert E. Krieger Publishing: Malabar, FL, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dellazizzo, L.; Potvin, S.; Giguère, S.; Landry, C.; Léveillé, N.; Dumais, A. Meta-review on the efficacy of psychological therapies for the treatment of substance use disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2024, 326, 115318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, M.; Thelander, S.; Jonsson, E. Treating Alcohol and Drug Abuse: An Evidence-Based Review; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dutra, L.; Stathopoulou, G.; Basden, S.L.; Leyro, T.M.; Powers, M.B.; Otto, M.W. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 2008, 165, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, L.; Minozzi, S.; Davoli, M.; Vecchi, S. Psychosocial combined with agonist maintenance treatments versus agonist maintenance treatments alone for treatment of opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 10, CD004147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, L.; Minozzi, S.; Davoli, M.; Vecchi, S. Psychosocial and pharmacological treatments versus pharmacological treatments for opioid detoxification. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 9, CD005031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairley, M.; Humphreys, K.; Joyce, V.R.; Bounhavong, M.; Trafton, J.; Combs, A.; Oliva, E.M.; Goldhaber-Fiebert, J.D.; Asch, S.M.; Brandeau, M.L.; et al. Cost-effectiveness of treatments for opioid use disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattick, R.P.; Breen, C.; Kimber, J.; Davoli, M. Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, 2003, CD002209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Opiod agonist maintenance treatment as an essential service. In Guidance on Mitigating Disruption of Services for Treatment of Opioid Dependence and Community Management of Opioid Overdose; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- ASAM. The ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: 2020 Focused Update. J. Addict. Med. 2020, 14, 1–91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beck, T.; Haasen, C.; Verthein, U.; Walcher, S.; Schuler, C.; Backmund, M.; Ruckes, C.; Reimer, J. Maintenance treatment for opioid dependence with slow-release oral morphine: A randomized cross-over, non-inferiority study versus methadone. Addiction 2014, 109, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.; Belackova, V.; Lintzeris, N. Supervised injectable opioid treatment for the management of opioid dependence. Drugs 2018, 78, 1339–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, M.; Minozzi, S.; Bo, A.; Amato, L. Slow-release oral morphine as maintenance therapy for opioid dependence (Review). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 6, CD009879. [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo-Joekes, E.; Brissette, S.; Marsh, D.C.; Lauzon, P.; Guh, D.; Anis, A.; Schechter, M.T. Diacetylmorphine versus methadone for the treatment of opioid addiction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo-Joekes, E.; Guh, D.; Brissette, S.; Marchand, K.; MacDonald, S.; Lock, K.; Harrison, S.; Janmohamed, A.; Anis, A.H.; Krausz, M.; et al. Hydromorphone compared with diacetylmorphine for long-term opioid dependence: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo-Joekes, E.; Brissette, S.; MacDonald, S.; Guh, D.; Marchand, K.; Jutha, S.; Harrison, S.; Janmohamed, A.; Zhang, D.Z.; Anis, A.H.; et al. Safety profile of injectable hydromorphone and diacetylmorphine for long-term severe opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 176, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokell, M.A.; Zaller, N.D.; Green, T.C.; Rich, J.D. Buprenorphine and buprenorphine/naloxone diversion, misuse, and illicit use: An international review. Curr. Drug Abus. Rev. 2011, 4, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowing, L.; Ali, R.; White, J.M.; Mbewe, D. Buprenorphine for managing opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2, CD002025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelmström, P.; Nordbeck, E.B.; Tiberg, F. Optimal dose of buprenorphine in opioid use disorder treatment: A review of pharmacodynamic and efficacy data. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2020, 46, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivasiy, R.; Madden, L.M.; Johnson, K.A.; Machavariani, E.; Ahmad, B.; Oliveros, D.; Tan, J.; Kil, N.; Altice, F.L. Retention and dropout from sublingual and extended-release buprenorphine treatment: A comparative analysis of commercially insured individuals with opioid use disorder in the United States. Int. J. Drug Policy 2025, 138, 104748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimber, J.; Larney, S.; Hickman, M.; Randall, D.; Degenhardt, L. Mortality risk of opioid substitution therapy with methadone versus buprenorphine: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, A.M.; Cousins, G.; Durand, L.; Barry, J.; Roland, F. Retention of patients in opioid substitution treatment: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, W.; Shoptaw, S.; Goodman-Meza, D. Depot buprenorphine injection in the management of opioid use disorder: From development to implementation. Subst. Abus. Rehabil. 2019, 10, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fareed, A.; Vayalapalli, S.; Casarella, J.; Drexler, K. Effect of buprenorphine dose on treatment outcome. J. Addict. Dis. 2012, 31, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.L.; Edgerton, R.D.; Watson, J.; Conley, N.; Agee, W.A.; Wilus, D.M.; Macmaster, S.A.; Bell, L.; Patel, P.; Godbole, A.; et al. Meta-analysis of primary care–delivered buprenorphine treatment retention outcomes. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2023, 49, 756–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connock, M.; Juarez-Garcia, A.; Jowett, S.; Frew, E.; Liu, Z.; Taylor, R.J.; Fry-Smith, A.; Day, E.; Lintzeris, N.; Roberts, T.; et al. Methadone and buprenorphine for the management of opioid dependence: A systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol. Assess. 2007, 11, 1–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattick, R.P.; Breen, C.; Kimber, J.; Davoli, M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2014, CD002207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santo, T.; Clark, B.; Hickman, M.; Grebely, J.; Campbell, G.; Sordo, L.; Chen, A.; Tran, L.T.; Bharat, C.; Padmanathan, P.; et al. Association of opioid agonist treatment with all-cause mortality and specific causes of death among people with opioid dependence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 979–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, D.J.; Shiner, B.; Hoyt, J.E.; Riblet, N.B.; Peltzman, T.; Teja, N.; Watts, B.V. A comparison of mortality rates for buprenorphine versus methadone treatments for opioid use disorder. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2023, 147, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sordo, L.; Barrio, G.; Bravo, M.J.; Indave, B.I.; Degenhardt, L.; Wiessing, L.; Ferri, M.; Pastor-Barriuso, R. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: Systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ 2017, 357, j1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, M.A.; Lofwall, M.R.; Walsh, S.L. Buprenorphine pharmacology review: Update on transmucosal and long-acting formulations. J. Addict. Med. 2019, 13, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyka, M. Novel long-acting buprenorphine medications for opioid dependence: Current update. Pharmacopsychiatry 2021, 54, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, P.; Ang, A.; Hillhouse, M.P.; Saxon, A.J.; Nielsen, S.; Wakim, P.G.; Mai, B.E.; Mooney, L.J.; Potter, J.S.; Blaine, J.D. Treatment outcomes in opioid-dependent patients with different buprenorphine/naloxone induction dosing patterns and trajectories. Am. J. Addict. 2015, 24, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degenhardt, L.; Clark, B.; MacPherson, G.; Leppan, O.; Nielsen, S.; Zahra, E.; Larance, B.; Kimber, J.; Martino-Burke, D.; Hickman, M.; et al. Buprenorphine versus methadone for the treatment of opioid dependence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and observational studies. Lancet Psychiatry 2023, 10, 386–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimas, J.; Hamilton, M.-A.; Gorfinkel, L.; Adam, A.; Cullen, W.; Wood, E. Retention in opioid agonist treatment: A rapid review and meta-analysis comparing observational studies and randomized controlled trials. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haber, P.S.; Elsayed, M.; Espinoza, D.; Lintzeris, N.; Veillard, A.S.; Hallinan, R. Constipation and other common symptoms reported by women and men in methadone and buprenorphine maintenance treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 181, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strang, J.; Reed, K.; Bogdanowicz, K.; Bell, J.; van der Waal, R.; Keen, J.; Beavan, P.; Baillie, S.; Knight, A. Randomised comparison of a novel oral lyophilisate versus existing buprenorphine sublingual tablets in opioid-dependent patients: A first-in-patient phase VII randomised open-label safety study. Eur. Addict. Res. 2017, 23, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang, J.; Knight, A.; Baillie, S.; Reed, K.; Bogdanowicz, K.; Bell, J. Norbuprenorphine and respiratory depression: Exploratory analyses with new lyophilised buprenorphine and sublingual buprenorphine. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2018, 56, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, K.; Knight, A.; Baillie, S.; Bogdanowicz, K.; Bell, J.; Strang, J. Switching between lyophilised and sublingual buprenorphine formulations in opioid-dependent patients: Observations on medication transfer during a safety and pharmacokinetic study. Heroin Addict. Relat. Clin. Probl. 2018, 20, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). Public Assessment Report: Espranor 2 mg and 8 mg Oral Lyophilisate (Buprenorphine Hydrochloride); UK/H/5385/001–02/DC; MHRA: London, UK, 2015.

- Langridge, M.; Bromley, S. Impact of introducing an alternative buprenorphine formulation on opioid substitution therapy supervision within UK prison settings. Prison Serv. J. 2022, 260, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Malta, M.; Varatharajan, T.; Russell, C.; Pang, M.; Bonato, S.; Fischer, B. Opioid-related treatment, interventions, and outcomes among incarcerated persons: A systematic review. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1003002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.E.; Roberts, W.; Reid, H.H.; Smith, K.M.Z.; Oberleitner, L.M.S.; McKee, S.A. Effectiveness of medication-assisted treatment for opioid use in prison and jail settings: A meta-analysis and systematic review. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2019, 99, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyka, M.; Laber, D. Efficacy of opioid maintenance in prison settings—How strong is the evidence? A narrative review. Forens. Psychiatr. Psychol. Kriminol. 2025, 19, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyseng-Williamson, K. Buprenorphine oral lyophilisate (Espranor) in the substitution treatment of opioid dependence: A profile of its use. Drugs Ther. Perspect. 2017, 33, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, D.; Kirkwood, J.E.M.; Doroshuk, M.L.; Kelmer, M.; Korownyk, C.S.; Ton, J.; Garrison, S.R. Opioid agonist therapy for opioid use disorder in primary versus specialty care. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2025, 9, CD013672. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, S.; Tse, W.C.; Larance, B. Opioid agonist treatment for people who are dependent on pharmaceutical opioids. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 2022, CD011117. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Test | Reference | Ratio T/R% | 90% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 2.22 | 1.79 | 124.44 | 95.76–161.71 |

| AUC0–t | 11.48 | 10.75 | 106.80 | 41.37–275.74 |

| AUC0–inf | 15.81 | 16.11 | 98.15 | 42.73–225.43 |

| Parameter | Test | Reference | Ratio T/R% | 90% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 6.11 | 7.53 | 81.17 | 58.96–111.73 |

| AUC0–t | 51.72 | 53.83 | 96.09 | 71.49–129.14 |

| AUC0–inf | 59.74 | 60.97 | 97.99 | 71.08–135.10 |

| Parameter | Test | Reference | Ratio T/R% | 90% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 5.77 | 4.45 | 129.51 | 118.94–141.02 |

| AUC0–t | 26.71 | 19.42 | 137.50 | 122.15–154.78 |

| AUC0–inf | 30.42 | 22.14 | 137.40 | 121.27–155.67 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Soyka, M.; Bolz, S. Buprenorphine Oral Lyophilisate for Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: Pharmacology and Clinical Efficacy. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19020270

Soyka M, Bolz S. Buprenorphine Oral Lyophilisate for Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: Pharmacology and Clinical Efficacy. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(2):270. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19020270

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoyka, Michael, and Svenja Bolz. 2026. "Buprenorphine Oral Lyophilisate for Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: Pharmacology and Clinical Efficacy" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 2: 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19020270

APA StyleSoyka, M., & Bolz, S. (2026). Buprenorphine Oral Lyophilisate for Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: Pharmacology and Clinical Efficacy. Pharmaceuticals, 19(2), 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19020270