Studying Candida Biofilms Across Species: Experimental Models, Structural Diversity, and Clinical Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Diversity Among Candida Species in Biofilm Formation

2.1. Molecular and Regulatory Networks Driving Biofilm Formation

2.2. Matrix Composition and Metabolic Adaptations

2.3. Candida Interactions Within Polymicrobial Biofilm

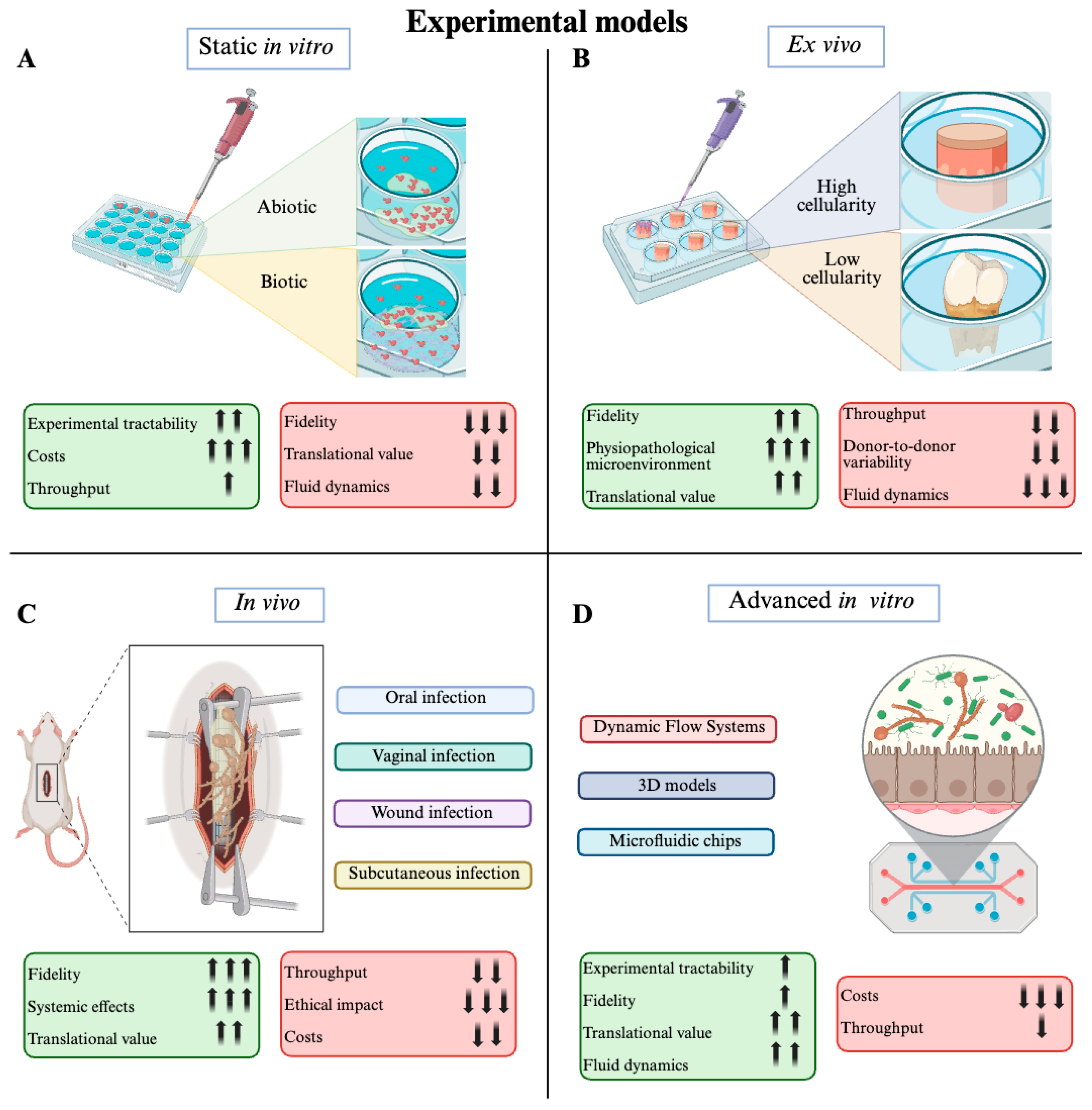

3. Experimental Models and Methods for Candida spp. Biofilm Investigation

3.1. Static In Vitro Models

- Inoculum load in terms of CFU/mL. Usually, the choice is between 104 and 108 CFU/mL; the method to assess the fungal load can also be a variable. Burker chamber, absorbance (600 nm), and McFarland turbidity standard can reach significant differences from expected to verified yeast load.

- Medium choice, inclusive of auxiliary chemicals like DMSO, dextrose, and so on. The most used mediums are YPD, BHI, TSB, and LB. The biochemical diversity of these mediums in terms of nutrients accessibility to yeasts is consistent.

- Days of incubation, significantly depending on the required development stage of tested biofilm. The time range can broadly be between 1 and 5 days, from early to full-mature biofilms.

- Incubation settings can also be particularly critical in terms of degree, CO2 percentage, and relative humidity (RH). The classic and advised approach is 37 °C, 5% CO2, and RH ≥ 90%.

3.2. Ex Vivo Models

3.2.1. Low-Cellularity Platforms

3.2.2. High-Cellularity Platforms

3.3. In Vivo Models

3.4. Advanced In Vitro Models

3.4.1. Dynamic Flow Systems

3.4.2. Three-Dimensional Models

3.4.3. Microfluidic Chips

| Model Description | Category | Investigated Candida spp. Species | Innovative Features | Year of Publication | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDC biofilm reactor | DFS | C. auris | Good mimic of physiological fluid dynamics. | 2025 | [124] |

| CDC biofilm reactor combined with colony drip flow reactors | DFS | C. albicans | Chronic wound infection simulation with the combination of dynamic and dripping flows. | 2020 | [129] |

| Drip flow biofilm reactor | DFS | C. albicans | Moist driveline exit-site by maintaining continuous oxygen and nutrient flow, supporting biofilm formation under low-shear, air–liquid interface conditions. | 2020 | [130] |

| BioFlux 1000Z Biofilm model | DFS | C. albicans | Continuous flow, capturing timelapse microscopic images and detachment dynamics under shear conditions. | 2022 | [85] |

| 3D printed denture base resins | 3D models | C. albicans | Good mimic of denture-related environment for Candida biofilm. | 2023 | [131] |

| 3D oral mucosal models | 3D models | C. albicans | Good mimic of host tissue; inflammatory response. | 2023 | [132] |

| 3D skin model | 3D models | C. albicans | Good mimic of host tissue; inflammatory response. | 2023 | [133] |

| 3D hydrogel—mesenchymal stem cell model | 3D models | C. albicans | Good potential for personalized medicine approaches. | 2025 | [126] |

| 3D air-liquid interface model | 3D models | C. albicans | Cellular multilayer platform to evaluate epithelial integrity. | 2025 | [134] |

| 3D full thickness skin model | 3D models | C. albicans | Incorporation of paramount human cellular lineages involved in skin colonization in a 3D setting. | 2022 | [135] |

| Immunocompetent intestine-on-chip | Microfluidic organ-on-chip | C. albicans | Cellular complexity; good mimic of fluid dynamic; inflammatory and immunity response. | 2019; 2024 | [128,136] |

| Microfluidic platform seeded with different yeast cells | Microfluidic chip | C. albicans | Microfluidic dynamic flow that allows one to deeply characterize adhesion on abiotic surfaces. | 2025 | [137] |

4. Clinical Impact of Candida Biofilm-Related Infections

4.1. Biofilm-Associated Infections in Clinical Practice

4.2. Antifungal Tolerance and Resistance

4.3. Therapeutic Challenges

Recent Antifungal Innovations and Their Activity Against Candida Biofilms

4.4. Clinical Implications and Translational Relevance

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| ALS | Agglutinin Like Sequence |

| BCR1 | Biofilm and Cell-wall Regulator 1 |

| BHI | Brain Heart Infusion |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CDR | Candida drug resistance |

| CFU | Colony Forming Units |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| CRBSI | Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections |

| CV | Crystal violet |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DPBS | Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| eDNA | Extracellular DNA |

| DFS | Dynamic flow systems |

| EAP | Enhanced Adherence to Polystyrene |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| EFG1 | Enhanced Filamentous Growth 1 |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency (US) |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| HWP1 | Hyphal Wall Protein 1 |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| IVIS | In Vivo Imaging System |

| LB | Luria–Bertani |

| MBEC | Minimum biofilm eradicating concentration |

| McF | McFarland standard unit |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| NAC | Non-albicans Candida |

| NRG1 | Negative Regulator of Growth 1 |

| OD | Optical Density |

| OPC | Oropharyngeal candidiasis |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PEG | Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy (tubo/sonda) |

| PE | Polyethylene |

| PenStrep | Penicllin Streptomycin solution |

| PCL | Polycaprolactone |

| PLA | Polylactic acid |

| PLLA | Poly L lactic acid |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PS | Polystyrene |

| PU | Polyurethane |

| RH | Relative humidity |

| rpm | Rounds per minute |

| RPMI | Roswell Park Memorial Institute |

| RVVC | Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| spp. | Species |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic acid (cycle) |

| TSB | Tryptic Soy Broth |

| US | United States |

| VVC | Vulvovaginal candidiasis |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| YPD | Yeast extract–Peptone–Dextrose |

References

- Vert, M.; Doi, Y.; Hellwich, K.H.; Hess, M.; Hodge, P.; Kubisa, P.; Rinaudo, M.; Schué, F. Terminology for Biorelated Polymers and Applications (IUPAC Recommendations 2012). Pure Appl. Chem. 2012, 84, 377–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, M.E.; O’toole, G.A. Microbial Biofilms: From Ecology to Molecular Genetics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000, 64, 847–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costerton, J.W.; Cheng, K.J.; Geesey, G.G.; Ladd, T.I.; Nickel, J.C.; Dasgupta, M.; Marrie, T.J. Bacterial Biofilms in Nature and Disease. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1987, 41, 435–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donlan, R.M. Biofilm Formation: A Clinically Relevant Microbiological Process. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 33, 1387–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, H.C.; Wingender, J.; Szewzyk, U.; Steinberg, P.; Rice, S.A.; Kjelleberg, S. Biofilms: An Emergent Form of Bacterial Life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, D.W. Global Incidence and Mortality of Severe Fungal Disease. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e428–e438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Fungal Priority Pathogens List to Guide Research, Development and Public Health Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 1–48.

- Ramage, G.; Rajendran, R.; Sherry, L.; Williams, C. Fungal Biofilm Resistance. Int. J. Microbiol. 2012, 2012, 528521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, J.; Mukherjee, P.K. Candida biofilms: Development, Architecture, and Resistance. Microbiol. Spectr. 2015, 3, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kojic, E.M.; Darouiche, R.O. Candida Infections of Medical Devices. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2004, 17, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumbarello, M.; Fiori, B.; Trecarichi, E.M.; Posteraro, P.; Losito, A.R.; de Luca, A.; Sanguinetti, M.; Fadda, G.; Cauda, R.; Posteraro, B. Risk Factors and Outcomes of Candidemia Caused by Biofilm-Forming Isolates in a Tertiary Care Hospital. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Peacock, J.E.; Tanner, D.C.; Morris, A.J.; Nguyen, M.L.; Snydman, D.R.; Wagener, M.M.; Yu, V.L. Therapeutic Approaches in Patients With Candidemia: Evaluation in a Multicenter, Prospective, Observational Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 1995, 155, 2429–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarnowski, R.; Sanchez, H.; Covelli, A.S.; Dominguez, E.; Jaromin, A.; Bernhardt, J.; Mitchell, K.F.; Heiss, C.; Azadi, P.; Mitchell, A.; et al. Candida albicans Biofilm–Induced Vesicles Confer Drug Resistance through Matrix Biogenesis. PLoS Biol. 2018, 16, e2006872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathé, L.; Van Dijck, P. Recent Insights into Candida albicans Biofilm Resistance Mechanisms. Curr. Genet. 2013, 59, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeater, K.M.; Chandra, J.; Cheng, G.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Zhao, X.; Rodriguez-Zas, S.L.; Kwast, K.E.; Gannoum, M.A.; Hoyer, L.L. Temporal Analysis of Candida albicans Gene Expression during Biofilm Development. Microbiology 2007, 153, 2373–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, E.P.; Bui, C.K.; Nett, J.E.; Hartooni, N.; Mui, M.C.; Andes, D.R.; Nobile, C.J.; Johnson, A.D. An Expanded Regulatory Network Temporally Controls Candida albicans Biofilm Formation. Mol. Microbiol. 2015, 96, 1226–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murillo, L.A.; Newport, G.; Lan, C.Y.; Habelitz, S.; Dungan, J.; Agabian, N.M. Genome-Wide Transcription Profiling of the Early Phase of Biofilm Formation by Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 2005, 4, 1562–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, J.V.; Mitchell, A.P. Candida albicans Biofilm Development and Its Genetic Control. Microbiol. Spectr. 2015, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.; Henriques, M.; Martins, A.; Oliveira, R.; Williams, D.; Azeredo, J. Biofilms of Non-Candida albicans Candida Species: Quantification, Structure and Matrix Composition. Med. Mycol. 2009, 47, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.; Negri, M.; Henriques, M.; Oliveira, R.; Williams, D.W.; Azeredo, J. Candida glabrata, Candida parapsilosis and Candida tropicalis: Biology, Epidemiology, Pathogenicity and Antifungal Resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 36, 288–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, H.; Bing, J.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, T.; Du, H.; Wang, H.; Huang, G. Filamentation in Candida auris, an Emerging Fungal Pathogen of Humans: Passage through the Mammalian Body Induces a Heritable Phenotypic Switch. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Bustos, V.; Pemán, J.; Ruiz-Gaitán, A.; Cabañero-Navalon, M.D.; Cabanilles-Boronat, A.; Fernández-Calduch, M.; Marcilla-Barreda, L.; Sigona-Giangreco, I.A.; Salavert, M.; Tormo-Mas, M.Á.; et al. Host–Pathogen Interactions upon Candida auris Infection: Fungal Behaviour and Immune Response in Galleria mellonella. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2022, 11, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janeczko, M.; Skrzypek, T. Relationships Between Candida auris and the Rest of the Candida World—Analysis of Dual-Species Biofilms and Infections. Pathogens 2025, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, K.; Urban, C.; Brunner, H.; Rupp, S. EFG1 Is a Major Regulator of Cell Wall Dynamics in Candida albicans as Revealed by DNA Microarrays. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 47, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, C.; Chen, J.; Yang, L.; Yang, Y.; Qi, H.; Li, R.; Cao, Y.; Miao, H. Shikonin Inhibits Candida albicans Biofilms via the Ras1-CAMP-Efg1 Signalling Pathway. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2023, 16, 2653–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyer, L.L.; Green, C.B.; Oh, S.H.; Zhao, X. Discovering the Secrets of the Candida albicans Agglutinin-like Sequence (ALS) Gene Family—A Sticky Pursuit. Med. Mycol. 2008, 46, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Palecek, S.P. EAP1, a Candida albicans Gene Involved in Binding Human Epithelial Cells. Eukaryot. Cell 2003, 2, 1266–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobile, C.J.; Nett, J.E.; Andes, D.R.; Mitchell, A.P. Function of Candida albicans Adhesin Hwp1 in Biofilm Formation. Eukaryot. Cell 2006, 5, 1604–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Zeng, N.; Li, C.; Li, Z.; Zhang, N.; Li, B. Fungal Biofilm Formation and Its Regulatory Mechanism. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yano, J.; Yu, A.; Fidel, P.L., Jr.; Noverr, M.C. Transcription Factors Efg1 and Bcr1 Regulate Biofilm Formation and Virulence during Candida albicans-Associated Denture Stomatitis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahni, N.; Yi, S.; Daniels, K.J.; Huang, G.; Srikantha, T.; Soll, D.R. Tec1 Mediates the Pheromone Response of the White Phenotype of Candida albicans: Insights into the Evolution of New Signal Transduction Pathways. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonhomme, J.; Chauvel, M.; Goyard, S.; Roux, P.; Rossignol, T.; D’Enfert, C. Contribution of the Glycolytic Flux and Hypoxia Adaptation to Efficient Biofilm Formation by Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 80, 995–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppuluri, P.; Pierce, C.G.; Thomas, D.P.; Bubeck, S.S.; Saville, S.P.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L. The Transcriptional Regulator Nrg1p Controls Candida albicans Biofilm Formation and Dispersion. Eukaryot. Cell 2010, 9, 1531–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mundodi, V.; Choudhary, S.; Smith, A.D.; Kadosh, D. Ribosome Profiling Reveals Differences in Global Translational vs Transcriptional Gene Expression Changes during Early Candida albicans Biofilm Formation. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e02195-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, C.; Vidanes, G.M.; Maguire, S.L.; Guida, A.; Synnott, J.M.; Andes, D.R.; Butler, G. Conserved and Divergent Roles of Bcr1 and CFEM Proteins in Candida parapsilosis and Candida albicans. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, L.A.; Riccombeni, A.; Grózer, Z.; Holland, L.M.; Lynch, D.B.; Andes, D.R.; Gácser, A.; Butler, G. The APSES Transcription Factor Efg1 Is a Global Regulator That Controls Morphogenesis and Biofilm Formation in Candida parapsilosis. Mol. Microbiol. 2013, 90, 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Butler, G. Development of a Gene Knockout System in Candida parapsilosis Reveals a Conserved Role for BCR1 in Biofilm Formation. Eukaryot. Cell 2007, 6, 1310–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossignol, T.; Ding, C.; Guida, A.; D’Enfert, C.; Higgins, D.G.; Butler, G. Correlation between Biofilm Formation and the Hypoxic Response in Candida parapsilosis. Eukaryot. Cell 2009, 8, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, C.M.; dos Santos, M.M.; Furlaneto-Maia, L.; Furlaneto, M.C. Adhesion and Biofilm Formation by the Opportunistic Pathogen Candida tropicalis: What Do We Know? Can. J. Microbiol. 2023, 69, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.J.; Wu, C.Y.; Yu, S.J.; Chen, Y.L. Protein Kinase A Governs Growth and Virulence in Candida tropicalis. Virulence 2018, 9, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purohit, D.; Gajjar, D. Tec1 and Ste12 Transcription Factors Play a Role in Adaptation to Low PH Stress and Biofilm Formation in the Human Opportunistic Fungal Pathogen Candida glabrata. Int. Microbiol. 2022, 25, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himratul-Aznita, W.H.; Jamil, N.A.; Jamaludin, N.H.; Nordin, M.A.F. Effect of Piper Betle and Brucea Javanica on the Differential Expression of Hyphal Wall Protein (HWP1) in Non-Candida albicans Candida (NCAC) Species. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 397268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, G.; Rasmussen, M.D.; Lin, M.F.; Santos, M.A.S.; Sakthikumar, S.; Munro, C.A.; Rheinbay, E.; Grabherr, M.; Forche, A.; Reedy, J.L.; et al. Evolution of Pathogenicity and Sexual Reproduction in Eight Candida Genomes. Nature 2009, 459, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño, I.; Pan, S.J.; Zupancic, M.; Hennequin, C.; Dujon, B.; Cormack, B.P. Telomere Length Control and Transcriptional Regulation of Subtelomeric Adhesins in Candida glabrata. Mol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 1246–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iraqui, I.; Garcia-Sanchez, S.; Aubert, S.; Dromer, F.; Ghigo, J.M.; D’Enfert, C.; Janbon, G. The Yak1p Kinase Controls Expression of Adhesins and Biofilm Formation in Candida glabrata in a Sir4p-Dependent Pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 1259–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Enfert, C.; Janbon, G. Biofilm Formation in Candida glabrata: What Have We Learnt from Functional Genomics Approaches? FEMS Yeast Res. 2016, 16, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louvet, M.; Li, J.; Brandalise, D.; Bachmann, D.; de Oyanguren, F.S.; Labes, D.; Jacquier, N.; Genoud, C.; Mucciolo, A.; Coste, A.T.; et al. Ume6-Dependent Pathways of Morphogenesis and Biofilm Formation in Candida auris. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0153124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nett, J.; Lincoln, L.; Marchillo, K.; Massey, R.; Holoyda, K.; Hoff, B.; VanHandel, M.; Andes, D. Putative Role of β-1,3 Glucans in Candida albicans Biofilm Resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.; Uppuluri, P.; Thomas, D.P.; Cleary, I.A.; Henriques, M.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L.; Oliveira, R. Presence of Extracellular DNA in the Candida albicans Biofilm Matrix and Its Contribution to Biofilms. Mycopathologia 2010, 169, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, D.; Henriques, M.; Silva, S. Portrait of Candida Species Biofilm Regulatory Network Genes. Trends Microbiol. 2017, 25, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, H.; Shang, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Chai, Y. Time Course Analysis of Candida albicans Metabolites during Biofilm Development. J. Proteome Res. 2012, 12, 2375–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, L.S.; Chauvel, M.; Sanchez, H.; van Wijlick, L.; Maufrais, C.; Cokelaer, T.; Sertour, N.; Legrand, M.; Sanyal, K.; Andes, D.R.; et al. Metabolic Reprogramming during Candida albicans Planktonic-Biofilm Transition Is Modulated by the Transcription Factors Zcf15 and Zcf26. PLoS Biol. 2024, 22, e3002693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, S.A.; Chasin, B.S.; Powell, B.; Gaur, N.K.; Lipke, P.N. Polymicrobial Bloodstream Infections Involving Candida Species: Analysis of Patients and Review of the Literature. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2007, 59, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.M.; Ovchinnikova, E.S.; Krom, B.P.; Schlecht, L.M.; Zhou, H.; Hoyer, L.L.; Busscher, H.J.; van der Mei, H.C.; Jabra-Rizk, M.A.; Shirtliff, M.E. Staphylococcus aureus Adherence to Candida albicans Hyphae Is Mediated by the Hyphal Adhesin Als3p. Microbiology 2012, 158, 2975–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, G.; Liu, Y.; Kim, D.; Li, Y.; Krysan, D.J.; Koo, H. Candida albicans Mannans Mediate Streptococcus mutans Exoenzyme GtfB Binding to Modulate Cross-Kingdom Biofilm Development in Vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, E.P.; Cowley, E.S.; Nobile, C.J.; Hartooni, N.; Newman, D.K.; Johnson, A.D. Anaerobic Bacteria Grow within Candida albicans Biofilms and Induce Biofilm Formation in Suspension Cultures. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, 2411–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriana, Y.; Widodo, A.D.W.; Arfijanto, M.V. Synergistic Interactions between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, Candida krusei, Candida parapsilosis as Well as Candida tropicalis in the Formation of Polymicrobial Biofilms. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 18, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, T.; Kudo, H.; Eguchi, S.; Matsumoto, A.; Oka, K.; Yamasaki, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Koshikawa, T.; Takemura, H.; Yamagishi, Y.; et al. Inhibitory Effects of Vaginal Lactobacilli on Candida albicans Growth, Hyphal Formation, Biofilm Development, and Epithelial Cell Adhesion. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1113401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadija, B.; Siddiqa, A.; Tara, T.; Zafar, S.; Saba, U.; Roohullah; Rubab, U.; Faryal, R. Candida-Candida and Candida-Staphylococcus Species Interactions in in-Vitro Dual-Species Biofilms. Int. J. Health Sci. 2022, 6, 1514–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, E.G.; Zarnowski, R.; Choy, H.L.; Zhao, M.; Sanchez, H.; Nett, J.E.; Andes, D.R. Conserved Role for Biofilm Matrix Polysaccharides in Candida auris Drug Resistance. mSphere 2019, 4, e00680-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Nett, J.; Andes, D.R. Fungal Biofilms: In Vivo Models for Discovery of Anti-Biofilm Drugs. Microbiol. Spectr. 2015, 3, E30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalheiro, M.; Teixeira, M.C. Candida Biofilms: Threats, Challenges, and Promising Strategies. Front Med. 2018, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, W.; Shao, J.; Li, Q.; Shi, G.; Wang, T.; Wu, D.; Wang, C. Extraction of Extracellular Matrix in Static and Dynamic Candida biofilms Using Cation Exchange Resin and Untargeted Analysis of Matrix Metabolites by Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (UPLC-Q-TOF-MS). Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, V.; Kissmann, A.K.; Firacative, C.; Rosenau, F. Biofilm-Associated Candidiasis: Pathogenesis, Prevalence, Challenges and Therapeutic Options. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eix, E.F.; Nett, J.E. How Biofilm Growth Affects Candida-Host Interactions. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 542412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nett, J.E.; Zarnowski, R.; Cabezas-Olcoz, J.; Brooks, E.G.; Bernhardt, J.; Marchillo, K.; Mosher, D.F.; Andes, D.R. Host Contributions to Construction of Three Device-Associated Candida albicans Biofilms. Infect. Immun. 2015, 83, 4630–4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, A.T.; Gehrke, L.; Vyas, J.M.; Harding, H.B. Human Brain Organoids: A New Model to Study Cryptococcus neoformans Neurotropism. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auld, D.S.; Coassin, P.A.; Coussens, N.P.; Hensley, P.; Klumpp-Thomas, C.; Michael, S.; Sittampalam, G.S.; Trask, O.J.; Wagner, B.K.; Weidner, J.R.; et al. Microplate Selection and Recommended Practices in High-throughput Screening and Quantitative Biology. In Assay Guidance Manual [Internet]; Markossian, S., Grossman, A., Baskir, H., Arkin, M., Auld, D., Austin, C., Baell, J., Brimacombe, K., Chung, T.D.Y., Coussens, N.P., Eds.; Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bordeleau, E.; Mazinani, S.A.; Nguyen, D.; Betancourt, F.; Yan, H. Abrasive Treatment of Microtiter Plates Improves the Reproducibility of Bacterial Biofilm Assays. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 32434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łysik, D.; Deptuła, P.; Chmielewska, S.; Bucki, R.; Mystkowska, J. Degradation of Polylactide and Polycaprolactone as a Result of Biofilm Formation Assessed under Experimental Conditions Simulating the Oral Cavity Environment. Materials 2022, 15, 7061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-González, N.; Shukla, A. Advances in Biomaterials for the Prevention and Disruption of Candida Biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 538602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, D.R.; Negri, M.; Silva, S.; Gorup, L.F.; de Camargo, E.R.; Oliveira, R.; Barbosa, D.B.; Henriques, M. Adhesion of Candida Biofilm Cells to Human Epithelial Cells and Polystyrene after Treatment with Silver Nanoparticles. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2014, 114, 410–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Soto, I.; McTiernan, C.; Gonzalez-Gomez, M.; Ross, A.; Gupta, K.; Suuronen, E.J.; Mah, T.F.; Griffith, M.; Alarcon, E.I. Mimicking Biofilm Formation and Development: Recent Progress in Vitro and in Vivo Biofilm Models. iScience 2021, 24, 102443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghofaily, M.; Alfraih, J.; Alsaud, A.; Almazrua, N.; Sumague, T.S.; Auda, S.H.; Alsalleeh, F. The Effectiveness of Silver Nanoparticles Mixed with Calcium Hydroxide against Candida albicans: An Ex Vivo Analysis. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanicharat, W.; Wanachantararak, P.; Poomanee, W.; Leelapornpisid, P.; Leelapornpisid, W. Potential of Bouea Macrophylla Kernel Extract as an Intracanal Medicament against Mixed-Species Bacterial-Fungal Biofilm. An in Vitro and Ex Vivo Study. Arch. Oral. Biol. 2022, 143, 105539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.; Gati, I.; Sionov, R.V.; Sahar-Helft, S.; Friedman, M.; Steinberg, D. Potential Combinatory Effect of Cannabidiol and Triclosan Incorporated into Sustained Release Delivery System against Oral Candidiasis. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leelapornpisid, W.; Novak-Frazer, L.; Qualtrough, A.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R. Effectiveness of D,L-2-Hydroxyisocaproic Acid (HICA) and Alpha-Mangostin against Endodontopathogenic Microorganisms in a Multispecies Bacterial–Fungal Biofilm in an Ex Vivo Tooth Model. Int. Endod. J. 2021, 54, 2243–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katalinić, I.; Pranjić, A.; Budimir, A.; Kanižaj, L.; Bago, I.; Rajić, V. Antimicrobial Effect of 2.5% Sodium Hypochlorite Irradiated with the 445 Nm Diode Laser against Bacterial Biofilms in Root Canal—In Vitro Pilot Study. Lasers Med. Sci. 2025, 40, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, S.S.; Rock, C.A.; Millenbaugh, N.J. Antifungal Peptide-Loaded Alginate Microfiber Wound Dressing Evaluated against Candida albicans in Vitro and Ex Vivo. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2024, 205, 114578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.A.S.; Krishnan, D.; Jothipandiyan, S.; Durai, R.; Hari, B.N.V.; Nithyanand, P. Cell-free supernatants of probiotic consortia impede hyphal formation and disperse biofilms of vulvovaginal candidiasis causing Candida in an ex-vivo model. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2024, 117, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaromin, A.; Zarnowski, R.; Markowski, A.; Zagórska, A.; Johnson, C.J.; Etezadi, H.; Kihara, S.; Mota-Santiago, P.; Nett, J.E.; Boyd, B.J.; et al. Liposomal Formulation of a New Antifungal Hybrid Compound Provides Protection against Candida Auris in the Ex Vivo Skin Colonization Model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2024, 68, e00955-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, S.R.; Esan, T.; Zarnowski, R.; Eix, E.; Nett, J.E.; Andes, D.R.; Hagen, T.; Krysan, D.J. Novel Keto-Alkyl-Pyridinium Antifungal Molecules Active in Models of In Vivo Candida albicans Vascular Catheter Infection and Ex Vivo Candida auris Skin Colonization. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2023, 67, e00081-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyarman, A.S.; Halim, L.A.; Jesslyn; Irma, H.A.; Richi, M.; Rizal, M.I. The Potential of Reuterin Derived from Indonesian Strain of Lactobacillus Reuteri against Endodontic Pathogen Biofilms in Vitro and Ex Vivo. Saudi Dent. J. 2023, 35, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, I.L.E.; Veiga, F.F.; de Castro-Hoshino, L.V.; Souza, M.; Malacrida, A.M.; Diniz, B.V.; dos Santos, R.S.; Bruschi, M.L.; Baesso, M.L.; Negri, M.; et al. Performance of Two Extracts Derived from Propolis on Mature Biofilm Produced by Candida albicans. Antibiotics 2022, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czechowicz, P.; Nowicka, J.; Neubauer, D.; Chodaczek, G.; Krzyżek, P.; Gościniak, G. Activity of Novel Ultrashort Cyclic Lipopeptides against Biofilm of Candida albicans Isolated from VVC in the Ex Vivo Animal Vaginal Model and BioFlux Biofilm Model—A Pilot Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasini, Z.; Roghanizad, N.; Fazlyab, M.; Pourhajibagher, M. Ex Vivo Efficacy of Sonodynamic Antimicrobial Chemotherapy for Inhibition of Enterococcus Faecalis and Candida albicans Biofilm. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2022, 40, 103113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, F.F.; de Castro-Hoshino, L.V.; Rezende, P.S.T.; Baesso, M.L.; Svidzinski, T.I.E. Insights on the Etiopathogenesis of Onychomycosis by Dermatophyte, Yeast and Non-Dermatophyte Mould in Ex Vivo Model. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 31, 1810–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjith, K.; Nagapriya, B.; Shivaji, S. Polymicrobial Biofilms of Ocular Bacteria and Fungi on Ex Vivo Human Corneas. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.J.; Cheong, J.Z.A.; Shanmuganayagam, D.; Kalan, L.R.; Nett, J.E. Modeling Candida Auris Colonization on Porcine Skin Ex Vivo. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2517, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eix, E.F.; Johnson, C.J.; Wartman, K.M.; Kernien, J.F.; Meudt, J.J.; Shanmuganayagam, D.; Gibson, A.L.F.; Nett, J.E. Ex Vivo Human and Porcine Skin Effectively Model Candida auris Colonization, Differentiating Robust and Poor Fungal Colonizers. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 225, 1791–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, M.V.; Johnson, C.J.; Kernien, J.F.; Patel, T.D.; Lam, B.C.; Cheong, J.Z.A.; Meudt, J.J.; Shanmuganayagam, D.; Kalan, L.R.; Nett, J.E. Candida auris Forms High-Burden Biofilms in Skin Niche Conditions and on Porcine Skin. mSphere 2020, 5, e00910-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, C.J.; Eix, E.F.; Lam, B.C.; Wartman, K.M.; Meudt, J.J.; Shanmuganayagam, D.; Nett, J.E. Augmenting the Activity of Chlorhexidine for Decolonization of Candida auris from Porcine Skin. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, K.; Vora, L.K.; Tekko, I.A.; Permana, A.D.; Domínguez-Robles, J.; Ramadon, D.; Chambers, P.; McCarthy, H.O.; Larrañeta, E.; Donnelly, R.F. Dissolving Microneedle Patches Loaded with Amphotericin B Microparticles for Localised and Sustained Intradermal Delivery: Potential for Enhanced Treatment of Cutaneous Fungal Infections. J. Control. Release 2021, 339, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, A.F.; Artunduaga Bonilla, J.J.; Zamith-Miranda, D.; Montalvão, B.; Veres, É.; Youngchim, S.; Tucker, C.; Draganski, A.; Gácser, A.; Nimrichter, L.; et al. Nitric Oxide-Releasing Microparticles: A Novel Treatment for Onychomycosis. Mol. Pharm. 2025, 22, 5567–5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerbu, D.; Seiser, S.; Phan-Canh, T.; Moser, D.; Freystätter, C.; Matiasek, J.; Kuchler, K.; Elbe-Bürger, A. Octenidine Effectively Reduces Candida auris Colonisation on Human Skin. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pati, B.A.; Kurata, W.E.; Horseman, T.S.; Pierce, L.M. Antibiofilm Activity of Chitosan/Epsilon-Poly-L-Lysine Hydrogels in a Porcine Ex Vivo Skin Wound Polymicrobial Biofilm Model. Wound Repair. Regen. 2021, 29, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Daniel, S.G.; Kim, H.E.; Koo, H.; Korostoff, J.; Teles, F.; Bittinger, K.; Hwang, G. Addition of Cariogenic Pathogens to Complex Oral Microflora Drives Significant Changes in Biofilm Compositions and Functionalities. Microbiome 2023, 11, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Mi, G.; Wang, M.; Webster, T.J. In Vitro and Ex Vivo Systems at the Forefront of Infection Modeling and Drug Discovery. Biomaterials 2019, 198, 228–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cometta, S.; Hutmacher, D.W.; Chai, L. In Vitro Models for Studying Implant-Associated Biofilms—A Review from the Perspective of Bioengineering 3D Microenvironments. Biomaterials 2024, 309, 122578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degli Esposti, L.; Squitieri, D.; Fusacchia, C.; Bassi, G.; Torelli, R.; Altamura, D.; Manicone, E.; Panseri, S.; Adamiano, A.; Giannini, C.; et al. Bioinspired Oriented Calcium Phosphate Nanocrystal Arrays with Bactericidal and Osteogenic Properties. Acta Biomater. 2024, 186, 470–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, T.L.; Vanek, M.E.; Gonzalez-Cabezas, C.; Marrs, C.F.; Foxman, B.; Rickard, A.H. In Vitro Model Systems for Exploring Oral Biofilms: From Single-Species Populations to Complex Multi-Species Communities. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 132, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, P.d.S.; Mendes, V.; Veiga, F.F.; Negri, M.; Svidzinski, T.I.E. Relevant Insights into Onychomycosis’ Pathogenesis Related to the Effectiveness Topical Treatment. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 169, 105640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Daigle, D.; Carviel, J.L. The Role of Biofilms in Onychomycosis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 74, 1241–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espana, E.M.; Birk, D.E. Composition, Structure and Function of the Corneal Stroma. Exp. Eye Res. 2020, 198, 108137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, A.F.; Kabir, M.; Chen, S.C.A.; Playford, E.G.; Marriott, D.J.; Jones, M.; Lipman, J.; McBryde, E.; Gottlieb, T.; Cheung, W.; et al. Candida Colonization as a Risk Marker for Invasive Candidiasis in Mixed Medical-Surgical Intensive Care Units: Development and Evaluation of a Simple, Standard Protocol. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 1324–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedha Hari, B.N.; Narayanan, N.; Dhevedaran, K. Efavirenz-Eudragit E-100 Nanoparticle-Loaded Aerosol Foam for Sustained Release: In-Vitro and Ex-Vivo Evaluation. Chem. Pap. 2015, 69, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josephs-Spaulding, J.; Singh, O.V. Medical Device Sterilization and Reprocessing in the Era of Multidrug-Resistant (MDR) Bacteria: Issues and Regulatory Concepts. Front. Med. Technol. 2020, 2, 587352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovaleva, J.; Peters, F.T.M.; van der Mei Mei, H.C.; Degener, J.E. Transmission of Infection by Flexible Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and Bronchoscopy. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 26, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trofa, D.; Gácser, A.; Nosanchuk, J.D. Candida parapsilosis, an Emerging Fungal Pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 21, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ménard, G.; Rouillon, A.; Cattoir, V.; Donnio, P.Y. Galleria mellonella as a Suitable Model of Bacterial Infection: Past, Present and Future. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 782733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, A.; Binder, U.; Kavanagh, K. Galleria mellonella Larvae as a Model for Investigating Fungal-Host Interactions. Front. Fungal Biol. 2022, 3, 893494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Li, Y.; Miao, H. The PP2A Catalytic Subunit PPH21 Regulates Biofilm Formation and Drug Resistance of Candida albicans. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wu, Q.; Weng, C.; Xu, S.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, W.; Xiong, X.; Chen, W.; Wei, X. Chloroquine Alone and Combined with Antifungal Drug Against Candida albicans Biofilms In Vitro and In Vivo via Autophagy Inhibition. Mycopathologia 2025, 190, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.-D.; Zhang, M.-X.; Yu, Q.-Y.; Wang, L.-L.; Han, Y.-X.; Gao, T.-L.; Lin, Y.; Tie, C.; Jiang, J.-D. Hyssopus Cuspidatus Boriss Volatile Extract (SXC): A Dual-Action Antioxidant and Antifungal Agent Targeting Candida albicans Pathogenicity and Vulvovaginal Candidiasis via Host Oxidative Stress Modulation and Fungal Metabolic Reprogramming. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y.; Luo, J.; Li, S.; Yang, Y.; Yan, L.; Zou, X. Impact of Clove Oil on Biofilm Formation in Candida albicans and Its Effects on Mice with Candida Vaginitis. Mycobiology 2025, 53, 661–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Xie, Q.; Liu, Y.; Huang, J.; Zeng, Q.; Li, X.; Rao, K.; Ning, J.; Zhao, M.; et al. Eradicating Fungal Biofilm-Based Infections by Ultrasound-Assisted Semiconductor Sensitized Upconversion Photodynamic Therapy. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persyn, A.; Rogiers, O.; Brock, M.; Velde, G.V.; Lamkanfi, M.; Jacobsen, I.D.; Himmelreich, U.; Lagrou, K.; Van Dijck, P.; Kucharíková, S. Monitoring of Fluconazole and Caspofungin Activity against In Vivo Candida glabrata Biofilms by Bioluminescence Imaging. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 63, e01555-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, L.; Whitely, C.; Tharmalingam, N.; Mishra, B.; Vera-Gonzalez, N.; Mylonakis, E.; Shukla, A.; Fuchs, B.B. Auranofin coated catheters inhibit bacterial and fungal biofilms in a murine subcutaneous model. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1135942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila, T.; Kong, E.F.; Montelongo-Jauregui, D.; Van Dijck, P.; Shetty, A.C.; McCracken, C.; Bruno, V.M.; Jabra-Rizk, M.A. Therapeutic Implications of C. albicans-S. aureus Mixed Biofilm in a Murine Subcutaneous Catheter Model of Polymicrobial Infection. Virulence 2021, 12, 835–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannala, G.K.; Rupp, M.; Walter, N.; Scholz, K.J.; Simon, M.; Riool, M.; Alt, V. Galleria mellonella as an Alternative in Vivo Model to Study Implant-Associated Fungal Infections. J. Orthop. Res.® 2023, 41, 2547–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, J.; Solis, M.; Higa, A.; Davis, S.C. Candida albicans Infections: A Novel Porcine Wound Model to Evaluate Treatment Efficacy. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Qi, Y.; Sun, W.; Qiu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ping, Y. Experimental Research on Fungal Inhibition Using Dissolving Microneedles of Terbinafine Hydrochloride Nanoemulsion for Beta-1,3-Glucanase. Nanoscale Adv. 2025, 7, 4636–4650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velde, G.V.; Kucharíková, S.; Van Dijck, P.; Himmelreich, U. Bioluminescence Imaging of Fungal Biofilm Development in Live Animals. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1098, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, A.; Jernej, L.; Liu, J.; Fefer, M.; Plaetzer, K. Chlorophyllin-Based Photodynamic Inactivation against Candidozyma auris Planktonic Cells and Dynamic Biofilm. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2025, 24, 1393–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clevers, H. Modeling Development and Disease with Organoids. Cell 2016, 165, 1586–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bicer, M.; Öztürk, E.; Sener, F.; Hakki, S.S.; Fidan, Ö. Antifungal Efficacy of 3D-Cultured Palatal Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Their Secreted Factors against Candida Albicans. ACS Infect. Dis. 2025, 11, 2894–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingber, D.E. Human Organs-on-Chips for Disease Modelling, Drug Development and Personalized Medicine. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 467–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaden, T.; Alonso-Roman, R.; Akbarimoghaddam, P.; Mosig, A.S.; Graf, K.; Raasch, M.; Hoffmann, B.; Figge, M.T.; Hube, B.; Gresnigt, M.S. Modeling of Intravenous Caspofungin Administration Using an Intestine-on-Chip Reveals Altered Candida albicans Microcolonies and Pathogenicity. Biomaterials 2024, 307, 122525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleman, L.; Purcell, L.; Thomas, H.; Westgate, S. Use of Internally Validated in Vitro Biofilm Models to Assess Antibiofilm Performance of Silver-Containing Gelling Fibre Dressings. J. Wound Care 2020, 29, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Y.; McGiffin, D.; Kure, C.; McLean, J.; Duncan, C.; Peleg, A.Y. In Vitro Evaluation of Medihoney Antibacterial Wound Gel as an Anti-Biofilm Agent Against Ventricular Assist Device Driveline Infections. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 605608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M.D.D.; Nunes, T.S.B.S.; Viotto, H.E.d.C.; Coelho, S.R.G.; de Souza, R.F.; Pero, A.C. Microbial Adhesion and Biofilm Formation by Candida albicans on 3D-Printed Denture Base Resins. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, S.J.; Foey, A.D.; Salih, V.M. An Organotypic Oral Mucosal Infection Model to Study Host-Pathogen Interactions. J. Tissue Eng. 2023, 14, 20417314231197310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, S.; Fischer, M.; Spange, S.; Beier, O.; Horn, K.; Tittelbach, J.; Wiegand, C. Cold Atmospheric Plasma Exerts Antimicrobial Effects in a 3D Skin Model of Cutaneous Candidiasis. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wronowska, E.; Guevara-Lora, I.; Brankiewicz, A.; Bras, G.; Zawrotniak, M.; Satala, D.; Karkowska-Kuleta, J.; Budziaszek, J.; Koziel, J.; Rapala-Kozik, M. Synergistic Effects of Candida albicans and Porphyromonas Gingivalis Biofilms on Epithelial Barrier Function in a 3D Aspiration Pneumonia Model. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1552395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzknecht, J.; Dubrac, S.; Hedtrich, S.; Galgóczy, L.; Marx, F.; Goldman, G.H. Small, Cationic Antifungal Proteins from Filamentous Fungi Inhibit Candida albicans Growth in 3D Skin Infection Models. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0029922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, M.; Gresnigt, M.S.; Last, A.; Wollny, T.; Berlinghof, F.; Pospich, R.; Cseresnyes, Z.; Medyukhina, A.; Graf, K.; Gröger, M.; et al. A Three-Dimensional Immunocompetent Intestine-on-Chip Model as in Vitro Platform for Functional and Microbial Interaction Studies. Biomaterials 2019, 220, 119396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinina, I.; Wilson, D. Candida albicans Goliath Cells Pioneer Biofilm Formation. mBio 2025, 16, e0342524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kean, R.; Ramage, G. Combined Antifungal Resistance and Biofilm Tolerance: The Global Threat of Candida auris. mSphere 2019, 4, e00458-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuza-Alves, D.L.; Silva-Rocha, W.P.; Chaves, G.M. An Update on Candida tropicalis Based on Basic and Clinical Approaches. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reusken, C.B.; Ieven, M.; Sigfrid, L.; Eckerle, I.; Koopmans, M. Laboratory Preparedness and Response with a Focus on Arboviruses in Europe. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018, 24, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijaya, M.; Halleyantoro, R.; Kalumpiu, J.F. Biofilm: The Invisible Culprit in Catheter-Induced Candidemia. AIMS Microbiol. 2023, 9, 467–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiencia-Carrera, M.B.; Cabezas-Mera, F.S.; Tejera, E.; Machado, A. Prevalence of Biofilms in Candida Spp. Bloodstream Infections: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajendran, R.; Sherry, L.; Nile, C.J.; Sherriff, A.; Johnson, E.M.; Hanson, M.F.; Williams, C.; Munro, C.A.; Jones, B.J.; Ramage, G. Biofilm Formation Is a Risk Factor for Mortality in Patients with Candida albicans Bloodstream Infection-Scotland, 2012-2013. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016, 22, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldini, S.; Posteraro, B.; Vella, A.; De Carolis, E.; Borghi, E.; Falleni, M.; Losito, A.R.; Maiuro, G.; Trecarichi, E.M.; Sanguinetti, M.; et al. Microbiologic and Clinical Characteristics of Biofilm-Forming Candida parapsilosis Isolates Associated with Fungaemia and Their Impact on Mortality. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018, 24, 771–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramage, G.; Williams, C. The Clinical Importance of Fungal Biofilms. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 84, 27–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, L.J. Candida Biofilms and Their Role in Infection. Trends Microbiol. 2003, 11, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramage, G.; Saville, S.P.; Thomas, D.P.; López-Ribot, J.L. Candida Biofilms: An Update. Eukaryot. Cell 2005, 4, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobile, C.J.; Johnson, A.D. Candida albicans Biofilms and Human Disease. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 69, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramage, G.; Mowat, E.; Jones, B.; Williams, C.; Lopez-Ribot, J. Our Current Understanding of Fungal Biofilms. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 35, 340–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cedeño-Pinargote, A.C.; Jara-Medina, N.R.; Pineda-Cabrera, C.C.; Cueva, D.F.; Erazo-Garcia, M.P.; Tejera, E.; Machado, A. Impact of Biofilm Formation by Vaginal Candida albicans and Candida glabrata Isolates and Their Antifungal Resistance: A Comprehensive Study in Ecuadorian Women. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papon, N.; Van Dijck, P. A Complex Microbial Interplay Underlies Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis Pathobiology. mSystems 2021, 6, e0106621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nett, J.E.; Andes, D.R. Contributions of the Biofilm Matrix to Candida Pathogenesis. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, L.; Kean, R.; McKloud, E.; O’Donnell, L.E.; Metcalfe, R.; Jones, B.L.; Ramage, G. Biofilms Formed by Isolates from Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis Patients Are Heterogeneous and Insensitive to Fluconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e01065-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nett, J.; Andes, D. Candida albicans Biofilm Development, Modeling a Host–Pathogen Interaction. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2006, 9, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taff, H.T.; Mitchell, K.F.; Edward, J.A.; Andes, D.R. Mechanisms of Candida Biofilm Drug Resistance. Future Microbiol. 2013, 8, 1325–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wuyts, J.; Van Dijck, P.; Holtappels, M. Fungal Persister Cells: The Basis for Recalcitrant Infections? PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, T.; Silva, S.; Henriques, M. Candida tropicalis Biofilm’s Matrix-Involvement on Its Resistance to Amphotericin B. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2015, 83, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Gow, N.A.R. The Role of the Candida Biofilm Matrix in Drug and Immune Protection. Cell Surf. 2023, 10, 100111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, E.; Hager, C.; Chandra, J.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Retuerto, M.; Salem, I.; Long, L.; Isham, N.; Kovanda, L.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; et al. The Emerging Pathogen Candida auris: Growth Phenotype, Virulence Factors, Activity of Antifungals, and Effect of SCY-078, a Novel Glucan Synthesis Inhibitor, on Growth Morphology and Biofilm Formation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e02396-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nett, J.E.; Crawford, K.; Marchillo, K.; Andes, D.R. Role of Fks1p and Matrix Glucan in Candida albicans Biofilm Resistance to an Echinocandin, Pyrimidine, and Polyene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 3505–3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taff, H.T.; Nett, J.E.; Zarnowski, R.; Ross, K.M.; Sanchez, H.; Cain, M.T.; Hamaker, J.; Mitchell, A.P.; Andes, D.R. A Candida Biofilm-Induced Pathway for Matrix Glucan Delivery: Implications for Drug Resistance. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFleur, M.D.; Kumamoto, C.A.; Lewis, K. Candida albicans Biofilms Produce Antifungal-Tolerant Persister Cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 3839–3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciofu, O.; Moser, C.; Jensen, P.Ø.; Høiby, N. Tolerance and Resistance of Microbial Biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, J.; Nobile, C.J. Antifungal Drug-Resistance Mechanisms in Candida Biofilms. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2023, 71, 102237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.K.; Chandra, J.; Kuhn, D.M.; Ghannoum, M.A. Mechanism of Fluconazole Resistance in Candida albicans Biofilms: Phase-Specific Role of Efflux Pumps and Membrane Sterols. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 4333–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkel, N.; Blaß, J.; Rogers, P.D.; Morschhäuser, J. Mutations in the Multi-Drug Resistance Regulator MRR1, Followed by Loss of Heterozygosity, Are the Main Cause of MDR1 Overexpression in Fluconazole-Resistant Candida albicans Strains. Mol. Microbiol. 2008, 69, 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, N.; Hsiao, C.H.; Yang, C.S.; Lin, H.C.; Yeh, L.K.; Fan, Y.C.; Sun, P.L. Colletotrichum Keratitis: A Rare yet Important Fungal Infection of Human Eyes. Mycoses 2020, 63, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, C.G.; Uppuluri, P.; Tristan, A.R.; Wormley, F.L.; Mowat, E.; Ramage, G.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L. A Simple and Reproducible 96-Well Plate-Based Method for the Formation of Fungal Biofilms and Its Application to Antifungal Susceptibility Testing. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1494–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.; Rodrigues, C.F.; Araújo, D.; Rodrigues, M.E.; Henriques, M. Candida Species Biofilms’ Antifungal Resistance. J. Fungi 2017, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidler, M.; Salvenmoser, S.; Müller, F.M.C. Liposomal Amphotericin B Eradicates Candida albicans Biofilm in a Continuous Catheter Flow Model. FEMS Yeast Res. 2010, 10, 492–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramage, G.; Jose, A.; Sherry, L.; Lappin, D.F.; Jones, B.; Williams, C. Liposomal Amphotericin B Displays Rapid Dose-Dependent Activity against Candida albicans Biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 2369–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, R.; Majoros, L. Antifungal Lock Therapy: An Eternal Promise or an Effective Alternative Therapeutic Approach? Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 74, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul Dimondi, V.; Townsend, M.L.; Johnson, M.; Durkin, M. Antifungal Catheter Lock Therapy for the Management of a Persistent Candida albicans Bloodstream Infection in an Adult Receiving Hemodialysis. Pharmacotherapy 2014, 34, e120–e127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walraven, C.J.; Lee, S.A. Antifungal Lock Therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 57, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriegl, L.; Egger, M.; Boyer, J.; Hoenigl, M.; Krause, R. New Treatment Options for Critically Important WHO Fungal Priority Pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2025, 31, 922–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jallow, S.; Govender, N.P. Ibrexafungerp: A First-in-Class Oral Triterpenoid Glucan Synthase Inhibitor. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almajid, A.; Bazroon, A.; Al-awami, H.M.; Albarbari, H.; Alqahtani, I.; Almutairi, R.; Alsuwayj, A.; Alahmadi, F.; Aljawad, J.; Alnimer, R.; et al. Fosmanogepix: The Novel Anti-Fungal Agent’s Comprehensive Review of in Vitro, in Vivo, and Current Insights From Advancing Clinical Trials. Cureus 2024, 16, e59210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, K.J.; Ibrahim, A.S. Fosmanogepix: A Review of the First-in-Class Broad Spectrum Agent for the Treatment of Invasive Fungal Infections. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceballos-Garzon, A.; Lebrat, J.; Holzapfel, M.; Josa, D.F.; Welsch, J.; Mercer, D. Antibiofilm Activity of Manogepix, Ibrexafungerp, Amphotericin B, Rezafungin, and Caspofungin against Candida Spp. Biofilms of Reference and Clinical Strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2025, 69, e00137-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos-Zambrano, L.J.; Gómez-Perosanz, M.; Escribano, P.; Bouza, E.; Guinea, J. The Novel Oral Glucan Synthase Inhibitor SCY-078 Shows in Vitro Activity against Sessile and Planktonic Candida Spp. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 1969–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Effron, G. Rezafungin—Mechanisms of Action, Susceptibility and Resistance: Similarities and Differences with the Other Echinocandins. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, J.; Ghannoum, M.A. CD101, A Novel Echinocandin, Possesses Potent Antibiofilm Activity against Early and Mature Candida albicans Biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01750-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colley, T.; Alanio, A.; Kelly, S.L.; Sehra, G.; Kizawa, Y.; Warrilow, A.G.S.; Parker, J.E.; Kelly, D.E.; Kimura, G.; Anderson-Dring, L.; et al. In Vitro and in Vivo Antifungal Profile of a Novel and Long-Acting Inhaled Azole, PC945, on Aspergillus Fumigatus Infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e02280-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanbiervliet, Y.; Van Nieuwenhuyse, T.; Aerts, R.; Lagrou, K.; Spriet, I.; Maertens, J. Review of the Novel Antifungal Drug Olorofim (F901318). BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfect, J.R. The Antifungal Pipeline: A Reality Check. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarif, L.; Graybill, J.R.; Perlin, D.; Najvar, L.; Bocanegra, R.; Mannino, R.J. Antifungal Activity of Amphotericin B Cochleates against Candida albicans Infection in a Mouse Model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 1463–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornely, O.A.; Sprute, R.; Bassetti, M.; Chen, S.C.A.; Groll, A.H.; Kurzai, O.; Lass-Flörl, C.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R.; Revathi, G.; et al. Global Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Candidiasis: An Initiative of the ECMM in Cooperation with ISHAM and ASM. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, e280–e293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Verweij, P.E.; Arendrup, M.C.; Arikan-Akdagli, S.; Bille, J.; Donnelly, J.P.; Jensen, H.E.; Lass-Flörl, C.; Richardson, M.D.; Akova, M.; et al. ESCMID Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Candida Diseases 2012: Diagnostic Procedures. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappas, P.G.; Kauffman, C.A.; Andes, D.R.; Clancy, C.J.; Marr, K.A.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Reboli, A.C.; Schuster, M.G.; Vazquez, J.A.; Walsh, T.J.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, e1–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, D.M.; George, T.; Chandra, J.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Ghannoum, M.A. Antifungal Susceptibility of Candida Biofilms: Unique Efficacy of Amphotericin B Lipid Formulations and Echinocandins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 1773–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobel, J.D.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Azie, N.; Angulo, D. In Vitro PH Activity of Ibrexafungerp against Fluconazole-Susceptible and -Resistant Candida Isolates from Women with Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, E.L.; Long, L.; Isham, N.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Barat, S.; Angulo, D.; Wring, S.; Ghannoum, M. A Novel 1,3-Beta-d-Glucan Inhibitor, Ibrexafungerp (Formerly SCY-078), Shows Potent Activity in the Lower PH Environment of Vulvovaginitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e02611-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofjan, A.K.; Mitchell, A.; Shah, D.N.; Nguyen, T.; Sim, M.; Trojcak, A.; Beyda, N.D.; Garey, K.W. Rezafungin (CD101), a next-Generation Echinocandin: A Systematic Literature Review and Assessment of Possible Place in Therapy. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2018, 14, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, P.G.; Vazquez, J.A.; Oren, I.; Rahav, G.; Aoun, M.; Bulpa, P.; Ben-Ami, R.; Ferrer, R.; Mccarty, T.; Thompson, G.R.; et al. Clinical Safety and Efficacy of Novel Antifungal, Fosmanogepix, for the Treatment of Candidaemia: Results from a Phase 2 Trial. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2023, 78, 2471–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, M.V.; Nett, J.E. Candida auris Infection and Biofilm Formation: Going Beyond the Surface. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2020, 7, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honraet, K.; Goetghebeur, E.; Nelis, H.J. Comparison of Three Assays for the Quantification of Candida Biomass in Suspension and CDC Reactor Grown Biofilms. J. Microbiol. Methods 2005, 63, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, I.B.; Meireles, A.; Gonçalves, A.L.; Goeres, D.M.; Sjollema, J.; Simões, L.C.; Simões, M. Standardized Reactors for the Study of Medical Biofilms: A Review of the Principles and Latest Modifications. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2018, 38, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Ma, S.; Leonhard, M.; Moser, D.; Schneider-Stickler, B. β-1,3-Glucanase Disrupts Biofilm Formation and Increases Antifungal Susceptibility of Candida albicans DAY185. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 108, 942–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; Ma, S.; Ding, T.; Ludwig, R.; Lee, J.; Xu, J. Enhancing the Antibiofilm Activity of β-1,3-Glucanase-Functionalized Nanoparticles Loaded With Amphotericin B Against Candida albicans Biofilm. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 815091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| C. albicans | C. parapsilosis | C. tropicalis | C. glabrata | C. auris | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morphological forms | Yeast Hyphae Pseudohyphae | Aggregated blastospores, Yeast Pseudohyphae | Yeast Hyphae Pseudohyphae | Blastospores | Yeast, filamentous forms/ Aggregating and non-aggregating forms | [18,19,20,21,22,23] |

| Key transcriptional factors | EGF1, BCR1, TEC, TYE7, NGE1 | EGF, BCR1, NDT80 | EGF1, BCR1, TEC, TYE7, NGE1, NDT80, WOR1, CSR1, RBT5, UME6 | STE12, TEC1 | UME6 | [24,25,31,32,33,35,36,39,40,41,47] |

| Main gene classes involved | ALS family, EAP family, HWP1 | RBT1 | ALS family, EAP family, HWP1 | EPA 3, 6, 7, GAS 2, DES2, MSS4, AVO2, SLM2, PKH2 | HGC1, ALS family, SCF1 | [26,27,28,37,38,42,44,45,46,47] |

| Characteristics of extracellular matrix | β-1,3-glucan as major component | Low levels of protein | Low levels of protein and carbohydrates | Primarily composed of hexosamines | Mannan–glucan complex | [48,50,60] |

| Metabolism pathway regulation | Downregulation of tricarboxylic acid cycle Down regulation of aerobic respiration Switch to a fermentative or metabolically quiescent state | [51] | ||||

| Explanted Tissue | Platform Typology | Investigated Species | Biofilm Formation Conditions | Year of Publication | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dental samples | Orthodontal infection platform | C. albicans | 105 CFU/mL; YPD medium; 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 14 days | 2024 | [74] |

| Lower human premolar teeth | Orthodontal infection platform | C. albicans in combination with E. faecalis and S. gordonii | 1 × 106 CFU/mL; BHI medium; 37 °C for 21 days | 2022 | [75] |

| Human teeth | Orthodontal infection platform | C. albicans | OD595 = 0.05 (CFU/mL load not specified); RPMI medium; 37 °C for 1 days | 2022 | [76] |

| Human single-root teeth | Orthodontal infection platform | C. albicans in combination with E. faecalis, L. rhamnosus, and S. gordonii | 1.5 × 108 CFU/mL; BHI medium; 37 °C for 21 days | 2021 | [77] |

| Human root canal | Orthodontal infection platform | C. albicans in combination with E. faecalis | 24 h inoculum in BHI from single colony; BHI medium; 37 °C for 14 days | 2025 | [78] |

| Porcine skin | Skin infection platform | C. albicans | 2 × 106 cells/mL; DMEM medium; 37 °C, 5% CO2, humidified, for 1 day | 2024 | [79] |

| Goat buccal mucosa | Vaginal infection platform | C. albicans, C. glabrata, and C. auris | 1% cell suspension; Simulated vaginal fluid supplemented with 17-ß-estradiol; 37 °C for 1 day | 2024 | [80] |

| Porcine skin | Skin infection platform | C. auris | 1 × 107 CFU/mL; Synthetic sweat media; 37 °C, 5% CO2, 1 day | 2023 | [81] |

| Porcine skin | Skin infection platform | C. auris | 1 × 107 CFU/mL; Synthetic sweat media (for C. auris), DPBS:DMEM:FBS semisolid agar (for the skin); 37 °C, 5% CO2, 1 day | 2023 | [82] |

| Human premolar teeth | Orthodontal infection platform | C. albicans in combination with E. faecalis, F. nucleatum, and P. gingivalis | 1 × 108 CFU/mL; BHI medium; 37 °C; 95% humidity; 1–2 days | 2023 | [83] |

| Human nails | Paronychia platform | C. albicans | 1 × 107 CFU/mL; 0.85% saline solution; 35 °C, humidified, 7 days | 2022 | [84] |

| Mice vaginal mucosa | Vaginal infection platform | C. albicans | 1–5 × 106 CFU/mL; 0.9% saline solution; 37 °C; with CO2, 1 day | 2022 | [85] |

| Single rooted single-canal maxillary anterior teeth | Orthodontal infection platform | C. albicans in combination with E. faecalis | 0.5 McF concentration; BHI medium; 37 °C, 20 rpm, 14 days | 2022 | [86] |

| Human nails | Paronychia platform | C. albicans | 1.2 × 107 CFU/mL; 0.85% saline solution; 35 °C, humidified, 7 days | 2022 | [87] |

| Human cadaveric cornea | Ocular infection platform | C. albicans | 104 CFU/mL; RPMI medium; 37 °C, 5% CO2, 1–2 days | 2022 | [88] |

| Porcine skin | Skin infection platform | C. auris | 107 CFU/mL; Synthetic sweat media (for C. auris), DPBS:DMEM:FBS semisolid agar (for the skin); 37 °C, humidified, 5% CO2, 1 day | 2022 | [89] |

| Human skin samples | Skin infection platform | C. auris | 107 CFU/mL; Synthetic sweat media (for C. auris), DPBS:DMEM:FBS semisolid agar (for the skin); 37 °C, humidified, 5% CO2, 1 day | 2022 | [90] |

| Porcine skin | Skin infection platform | C. auris | 107 CFU/mL; Synthetic sweat media (for C. auris), DPBS:DMEM:FBS semisolid agar (for the skin); 37 °C, humidified, 5% CO2, 1 day | 2020 | [91] |

| Porcine skin | Skin infection platform | C. auris | 107 CFU/mL; Synthetic sweat media (for C. auris), DPBS:DMEM:FBS semisolid agar (for the skin); 37 °C, humidified, 5% CO2, 1 day | 2021 | [92] |

| Neonatal porcine skin | Skin infection platform | C. albicans | 6 × 106 CFU/mL (subcutaneous); Sabouraud dextrose broth; 37 °C, 3 days | 2021 | [93] |

| Human nails | Onychomycosis platform | C. albicans | 106 CFU/mL; RPMI/1%PenStrp; 37 °C, 2 days | 2025 | [94] |

| Human skin samples | Skin infection platform | C. auris | ≈3.3 × 107 CFU/mL; DMEM/10%FBS/1%PenStrp; 37 °C, 6 h | 2025 | [95] |

| Porcine skin | Skin infection platform | C. albicans in combination with S. aureus and P. aeruginosa | ≈6 × 105 CFU/mL; Sabouraud dextrose broth; 37 °C, 5% CO2, 2 or 3 days | 2021 | [96] |

| Animal Species | Infection Model | Investigated Candida spp. Species | Infection/Biofilm Formation Conditions | Year of Publication | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse (immunodeficient CD-1) | Oral candidiasis | C. albicans | Swabbing all mucosal surfaces with cotton applicators saturated in a yeast suspension (108 CFU/mL). | 2025 | [112,113] |

| Mouse (CD-1) with induced false estrus (estradiol benzoate injections) | Vulvovaginal candidiasis | C. albicans | These mice were intravaginally inoculated with 106–107 CFU of Candida. This inoculation procedure was performed daily for 3–7 consecutive days. | 2025 | [114,115] |

| Mouse (Male BALB/c) | Wound infection | C. albicans | Two 6 mm diameter open wound was created on the back of the mice using a skin punch, and 10 μL Candida albicans suspension (2 × 108 CFU mL−1) was inoculated onto the wound. | 2025 | [116] |

| Mouse (BALB/c) | Subcutaneous infection | C. glabrata; C. albicans alone and mixed with S. aureus | Catheter pieces seeded with 106 CFU/mL of Candida strain (90 min) were implanted on the back/flank of the animal. | 2019; 2023; 2021 | [117,118,119] |

| Galleria mellonella | Implant-associated infection | C. albicans, C. krusei | Stainless steel and titanium K-wires seeded with 106 CFU/mL of Candida strain (overnight) were implanted in the rear part of the larvae through piercing the cuticle. | 2023 | [120] |

| Sus scrofa domesticus | Wound infection | C. albicans | Eighty-one second-degree burn wounds were made in the paravertebral and thoracic area on each animal by using specially designed heated cylindrical brass rods. A 108 CFU/mL Candida suspension was deposited into the center of each burn. | 2022 | [121] |

| New Zealand white rabbit | Onychomycosis model | C. albicans | 106 CFU/mL of Candida suspension was injected into the proximal nail folds of the left and right forepaws of rabbits. | 2025 | [122] |

| Clinical Setting | Biofilm Relevance | Key Species |

|---|---|---|

| Bloodstream infections (CRBSI) | Reservoir for persistent candidemia; ↑ mortality [142,143] | C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, C. auris |

| Mucosal infections (OPC, VVC, RVVC) | Chronicity, recurrence, drug tolerance [9,149,153] | C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. krusei, C. tropicalis |

| Medical devices (urinary catheters, prostheses, heart valves, endotracheal tubes) | Persistent infections, refractory to antifungals [145,146] | C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. auris |

| Gastrointestinal tract (PEG tubes) | Diarrhea, device degradation, microbial translocation → sepsis [152] | C. albicans, C. tropicalis |

| Chronic wounds (diabetic foot, surgical wounds, pressure ulcers) | Polymicrobial biofilms with S. aureus, P. aeruginosa [62] | C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. glabrata |

| Nosocomial outbreaks (ICU, skin, fomites) | Multidrug resistance + strong biofilm persistence [138] | C. auris |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Squitieri, D.; Rizzo, S.; Torelli, R.; Mariotti, M.; Sanguinetti, M.; Cacaci, M.; Bugli, F. Studying Candida Biofilms Across Species: Experimental Models, Structural Diversity, and Clinical Implications. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010008

Squitieri D, Rizzo S, Torelli R, Mariotti M, Sanguinetti M, Cacaci M, Bugli F. Studying Candida Biofilms Across Species: Experimental Models, Structural Diversity, and Clinical Implications. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleSquitieri, Damiano, Silvia Rizzo, Riccardo Torelli, Melinda Mariotti, Maurizio Sanguinetti, Margherita Cacaci, and Francesca Bugli. 2026. "Studying Candida Biofilms Across Species: Experimental Models, Structural Diversity, and Clinical Implications" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010008

APA StyleSquitieri, D., Rizzo, S., Torelli, R., Mariotti, M., Sanguinetti, M., Cacaci, M., & Bugli, F. (2026). Studying Candida Biofilms Across Species: Experimental Models, Structural Diversity, and Clinical Implications. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010008