Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles from Paullinia cupana Kunth Leaf: Effect of Seasonality and Preparation Method of Aqueous Extracts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chromatographic Profile of the Metabolite Composition of Aqueous Extracts Characterized by UHPLC-HRMS/MS

2.2. Quantification of Total Phenol Compounds (TPCs) and Antioxidant Potential

2.3. Optical Properties by UV-Vis Spectrophotometry

2.4. Stability Analyses by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) and Zeta Potential

2.5. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA)

2.6. Morphological Analyses (TEM) and Elemental Composition (EDX)

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Reagents

3.2. Procedures for Collecting Plant Material and Preparing Aqueous Extracts from Paullinia cupana Leaves

3.3. UHPLC-HRMS/MS Analyses of Seasonal Aqueous Leaf Extracts of Paullinia cupana

3.3.1. Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography–High Resolution Mass Spectrometry/Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC-HRMS/MS)

3.3.2. Determination of Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

3.3.3. Antioxidant Capacity for Eliminating DPPH and ABTS Free Radicals

3.4. Biogenic Synthesis of AgNPs

3.5. UV/Vis Spectrophotometry

3.6. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) and Electrophoretic Mobility (Zeta Potential)

3.7. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA)

3.8. Morphology (Transmission Electron Microscopy—TEM) and Elementary Composition (Energy-Dispersive X-ray—EDX) of AgNPs

3.9. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qin, K.; Liu, F.; Zhang, C.; Deng, R.; Fernie, A.R.; Zhang, Y. Systems and Synthetic Biology for Plant Natural Product Pathway Elucidation. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira De Azevedo, G.; Lima De Souza, G.; Leonarski, E.; Lotas, K.M.; Barroso Da Silva, G.H.; Miguel Batista, F.R.; Cesca, K.; De Oliveira, D.; Mathias Pereira, A.; Sodré Souza, L.D.S. Valorization of Guarana (Paullinia cupana) Production Chain Waste—A Review of Possible Bioproducts. Resources 2025, 14, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadoná, F.C.; Dantas, R.F.; De Mello, G.H.; Silva-Jr, F.P. Natural Products Targeting into Cancer Hallmarks: An Update on Caffeine, Theobromine, and (+)-Catechin. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 7222–7241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Giglio, A.; del Giglio, A. Chapter 6—Using Paullinia cupana (Guarana) to Treat Fatigue and Other Symptoms of Cancer and Cancer Treatment. In Bioactive Nutraceuticals and Dietary Supplements in Neurological and Brain Disease; Watson, R.R., Preedy, V.R., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 57–63. ISBN 978-0-12-411462-3. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, K.N.; de Freitas, A.A.; Cunha, L.H.; Faraco, A.A.G.; de Pádua, R.M.; Braga, F.C.; Vianna-Soares, C.D.; Castilho, R.O. A Rapid Simultaneous Determination of Methylxanthines and Proanthocyanidins in Brazilian Guaraná (Paullinia cupana Kunth.). Food Chem. 2018, 239, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo-Coupe, N.; Da Rocha, H.R.; Hutyra, L.R.; Da Araujo, A.C.; Borma, L.S.; Christoffersen, B.; Cabral, O.M.R.; De Camargo, P.B.; Cardoso, F.L.; Da Costa, A.C.L.; et al. What Drives the Seasonality of Photosynthesis across the Amazon Basin? A Cross-Site Analysis of Eddy Flux Tower Measurements from the Brasil Flux Network. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 182–183, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, E.D.O.; Vieira, M.A.R.; Ferreira, M.I.; Fernandes, A., Jr.; Marques, M.O.M.; Minatel, I.O.; Albano, M.; Sambo, P.; Lima, G.P.P. Seasonality Effects on Chemical Composition, Antibacterial Activity and Essential Oil Yield of Three Species of Nectandra. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaspar, D.P.; Chagas, G.C.A., Jr.; De Aguiar Andrade, E.H.; Nascimento, L.D.D.; Chisté, R.C.; Ferreira, N.R.; Martins, L.H.D.S.; Lopes, A.S. How Climatic Seasons of the Amazon Biome Affect the Aromatic and Bioactive Profiles of Fermented and Dried Cocoa Beans? Molecules 2021, 26, 3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, L.V.D.N.; Cordeiro, M.F.; Lins, E.T.U.L.; Sampaio, M.C.P.D.; De Mello, G.S.V.; Da Costa, V.D.C.M.; Marques, L.L.M.; Klein, T.; De Mello, J.C.P.; Cavalcanti, I.M.F.; et al. Evaluation of Antibacterial, Antineoplastic, and Immunomodulatory Activity of Paullinia cupana Seeds Crude Extract and Ethyl-Acetate Fraction. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 2016, 1203274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, L.L.M.; Panizzon, G.P.; Aguiar, B.A.A.; Simionato, A.S.; Cardozo-Filho, L.; Andrade, G.; De Oliveira, A.G.; Guedes, T.A.; Mello, J.C.P.D. Guaraná (Paullinia cupana) Seeds: Selective Supercritical Extraction of Phenolic Compounds. Food Chem. 2016, 212, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, M.K. (Ed.) Plant-Derived Bioactives: Production, Properties and Therapeutic Applications; Springer: Singapore, 2020; ISBN 978-981-15-1760-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, N.; Marboh, E.; Gupta, A.; Kumar, A.; Anal, A.D.; Nath, V. Variation in leaf phenol content during flowering in litchi (Litchi chinensis SONN.). J. Exp. Biol. Agric. Sci. 2019, 7, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, A.C.S.; Júnior, J.S.A.; Moraes, W.P.; Silva, H.N.P.; Fernandes, G.S.T.; Souza, J.; Azevedo, M.M.R.; Lima, A.K.O.; Silveira, T.S.; Gusmão, J.G.V.; et al. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Assisted by Amazonian Stingless Honeybee from Melipona Compressipes Manaosensis and Application in Tissue Repair of Infected Wounds in Wistar Rats. Regen. Eng. Transl. Med. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, K.J.S.; Abreu, A.C.S.; de Souza, S.G.B.; de Oliveira, J.T.L.B.; de Sousa, C.; Vasconcelos, A.A.; Ramos Azevedo, M.M.; de Souza, J.; Rabelo da Silva, S.K.; Gul, K.; et al. Study of Brazilian Amazon Honeybees’ (Melipona scutellaris and Apis mellifera) Properties in Healing Infected Skin Wounds in Wistar Rats. Curr. Biotechnol. 2025, 14, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.F.; dos Santos Batista, J.; da Silva, A.M.B.; da Silva, E.M.; Laier, L.O.; Dutra, J.L.; da Cruz Júnior, J.W.; Perotti, G.F.; Cividini Neiva, E.G.; de Souza, E.A.; et al. Exploring the Electrochemical Properties of Platinum Nanoparticles Synthesized by Green Synthesis Using Paullinia cupana Extract. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2025, 322, 118632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggia, I.; Dalcin, A.J.F.; Ourique, A.F.; da Cruz, I.B.M.; Ribeiro, E.E.; Mitjans, M.; Vinardell, M.P.; Gomes, P. Protective Effect of Guarana-Loaded Liposomes on Hemolytic Activity. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 187, 110636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggia, I.; Gomes, P.; Dalcin, A.J.; Ourique, A.F.; Mânica da Cruz, I.B.; Ribeiro, E.E.; Mitjans, M.; Vinardell, M.P. Profiling and Evaluation of the Effect of Guarana-Loaded Liposomes on Different Skin Cell Lines: An In Vitro Study. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, A.S.; Jeyaraj, M.; Selvakumar, M.; Abirami, E. Pharmacological activity of silver nanoparticles, ethanolic extract from Justicia gendarussa (burm) f plant leaves. Res. J. Life Sci. Bioinform. Pharm. Chem. Sci. 2019, 5, 462–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kováč, J.; Slobodníková, L.; Trajčíková, E.; Rendeková, K.; Mučaji, P.; Sychrová, A.; Bittner Fialová, S. Therapeutic Potential of Flavonoids and Tannins in Management of Oral Infectious Diseases—A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, B.A.; Rahman, R.M.A.; Appleton, I. Mechanisms of Action of Green Tea Catechins, with a Focus on Ischemia-Induced Neurodegeneration. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2006, 17, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, G.A.N.D.; Schimpl, F.C.; Ribeiro, M.D.; Scherer Filho, C.; Valente, M.S.F.; Silva, J.F.D. Methylxanthine and Polyphenol Distribution in Guarana Cultivars. Sci. Plena 2024, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.K.O.; Souza, L.M.D.S.; Reis, G.F.; Tavares Júnior, A.G.; Araújo, V.H.S.; Santos, L.C.D.; Silva, V.R.P.D.; Chorilli, M.; Braga, H.D.C.; Tada, D.B.; et al. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Extracts from Different Parts of the Paullinia cupana Kunth Plant: Characterization and In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.K.O.; Vieira, Í.R.S.; Souza, L.M.D.S.; Florêncio, I.; Silva, I.G.M.D.; Tavares, A.G., Jr.; Machado, Y.A.A.; Santos, L.C.D.; Taube, P.S.; Nakazato, G.; et al. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Paullinia cupana Kunth Leaf Extract Collected in Different Seasons: Biological Studies and Catalytic Properties. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, G.; Silva, E.L.; Filho, E.; Canuto, K.; De Brito, E.; De Jesus, R. 1H Quantitative Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Principal Component Analysis as Tool for Discrimination of Guarana Seeds from Different Geographic Regions of Brazil. In Proceedings of the XIII International Conference on the Applications of Magnetic Resonance in Food Science, Karlsruhe, Germany, 7–10 June 2016; IM Publications: Chichester, UK, 2016; p. 21, ISBN 978-1-906715-24-3. [Google Scholar]

- Gobbo-Neto, L.; Lopes, N.P. Plantas medicinais: Fatores de influência no conteúdo de metabólitos secundários. Quím. Nova 2007, 30, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.-A.-M.; Phan, H.-V.-T.; Thao, V.-T.-M.; Nguyen, M.-K.; Dang, T.T.; Do, N.-T.; Dang, L.-T.-C.; Huynh, T.-M.-S.; Dao, M.-T.; Nguyen, V.-K.; et al. Green in Situ Fabrication of Silver Nanoparticles Coated Silk Using Aqueous Leaf Extract of Premna serratifolia (L.) for Antibacterial Textiles. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 72, 106976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailova, E.O. Green Silver Nanoparticles: An Antibacterial Mechanism. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botinelly Nogueira, R.; Manzato, L.; Silveira Gurgel, R.; Melchionna Albuquerque, P.; Magalhães Teixeira Mendes, F.; Hotza, D. Optimized Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles from Guarana Seed Skin Extract with Antibacterial Potential. Green Process. Synth. 2025, 14, 20230210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, W.A.; Chakraborty, S.; Islam, R.U. Photocatalytic Degradation of Rhodamine B under UV Irradiation Using Shorea Robusta Leaf Extract-Mediated Bio-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 17, 2059–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Sharma, S.; Alam, M.K.; Singh, V.N.; Shamsi, S.F.; Mehta, B.R.; Fatma, A. Rapid Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Dried Medicinal Plant of Basil. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2010, 81, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amar, A.A.; Putra, E.D.L.; Satria, D.; Sitorus, P.; Lee, H.-L.; Waruwu, S.B.; Muhammad, M. Biosynthesis and Biological Activity of Silver Nanoparticles from Zanthoxylum Acanthopodium Fruits. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 52, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenny, S.; Zuhra, C.F. Antibacterial Properties of Breadfruit (Artocarpus alitilis) Leaves Extracts. AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 2626, 030009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leandrini de Oliveira, A.L.; Perea Muniz, M.; Moura Araújo da Silva, F.; Holanda do Nascimento, A.; dos Santos-Barnett, T.C.; Batista Gomes, F.; Massayoshi Nunomura, S.; Krug, C. Chemical Composition of Guarana Flowers and Nectar and Their Ecological Significance. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2024, 112, 104769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.; Zaky, M.Y.; Rashed, M.M.A.; Almoiliqy, M.; Al-Dalali, S.; Eldin, Z.E.; Bashari, M.; Cheikhyoussef, A.; Alsalamah, S.A.; Alghonaim, M.I.; et al. UPLC-qTOF-MS Phytochemical Profile of Commiphora gileadensis Leaf Extract via Integrated Ultrasonic-Microwave-Assisted Technique and Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles for Enhanced Antibacterial Properties. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2024, 107, 106923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, M.d.S.; Soares, M.J.; Soares-Freitas, R.A.M.; Sampaio, G.R.; Pinaffi-Langley, A.C.d.C.; dos Santos, O.V.; De Camargo, A.C.; Rogero, M.M.; Torres, E.A.F.d.S. Effect of Guarana Seed Powder on Cholesterol Absorption in Vitro and in Caco-2 Cells. Food Res. Int. 2022, 162, 111968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, J.; Sobral, P.J.D.A. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of Ethanolic Extracts of Guarana, Boldo, Rosemary and Cinnamon. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2017, 20, e2016024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuskoski, E.M. Capillary Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (CGC-MS) Analysis and Antioxidant Activities of Phenolic and Components of Guarana and Derivatives. Open Anal. Chem. J. 2012, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majhenič, L.; Škerget, M.; Knez, Ž. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity of Guarana Seed Extracts. Food Chem. 2007, 104, 1258–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Ambigaipalan, P. Phenolics and Polyphenolics in Foods, Beverages and Spices: Antioxidant Activity and Health Effects—A Review. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 18, 820–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Mumper, R.J. Plant Phenolics: Extraction, Analysis and Their Antioxidant and Anticancer Properties. Molecules 2010, 15, 7313–7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, Q.D.; Angkawijaya, A.E.; Tran-Nguyen, P.L.; Huynh, L.H.; Soetaredjo, F.E.; Ismadji, S.; Ju, Y.-H. Effect of Extraction Solvent on Total Phenol Content, Total Flavonoid Content, and Antioxidant Activity of Limnophila aromatica. J. Food Drug Anal. 2014, 22, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzahra, R.; Yanti, D.D.; Mahendra, I.P.; Saputra, M.Y.; Andreani, A.S.; Amin, A.K.; Aji, A. Green Synthesis of Ag/AgCl Nanocomposites Derived from Muntingia calabura L. Leaves Extract: Antioxidant Properties and Catalytic Activity in Methylene Blue Degradation. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2024, 105, 6013–6033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafhala, L.; Khumalo, N.; Zikalala, N.E.; Azizi, S.; Cloete, K.J.; More, G.K.; Kamika, I.A.; Mokrani, T.; Zinatizadeh, A.A.; Maaza, M. Antibacterial and Cytotoxicity Activity of Green Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles Using Aqueous Extract of Naartjie (Citrus unshiu) Fruit Peels. Emerg. Contam. 2024, 10, 100348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evanoff, D., Jr.; Chumanov, G. Synthesis and optical properties of silver nanoparticles and arrays. ChemPhysChem 2005, 6, 1221–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aji, A.; Oktafiani, D.; Yuniarto, A.; Amin, A.K. Biosynthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Using Kapok (Ceiba Pentandra) Leaf Aqueous Extract and Investigating Their Antioxidant Activity. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1270, 133906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, M.J.; Hati Boruah, J.L.; Saikia, R.; Dutta, U.; Kakati, D. Synthesis, Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Bioevaluation of Silver Nanoparticles Using Leaf Extract of Sarcochlamys pulcherrima. Next Nanotechnol. 2024, 5, 100063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, K.L.; Coronado, E.; Zhao, L.L.; Schatz, G.C. The Optical Properties of Metal Nanoparticles: The Influence of Size, Shape, and Dielectric Environment. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 668–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aji, A.; Lasendo, M.; Saputra, M.Y.; Putri, R.A.; Nareswari, T.L. Eco-Friendly Fabrication of Silver Nanoparticles via Acacia Mangium: Exploring Antioxidant and Antibacterial Potentials. Chem. Pap. 2025, 79, 4521–4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, A.; Lamichhane, L.; Adhikari, A.; Gyawali, G.; Acharya, D.; Baral, E.R.; Chhetri, K. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Artemisia vulgaris Extract and Its Application toward Catalytic and Metal-Sensing Activity. Inorganics 2022, 10, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.K.O.; Vasconcelos, A.A.; Kobayashi, R.K.T.; Nakazato, G.; Braga, H.D.C.; Taube, P.S. Green Synthesis: Characterization and Biological Activity of Silver Nanoparticles Using Aqueous Extracts of Plants from the Arecaceae Family. Acta Sci. Technol. 2021, 43, e52011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Smita, K.; Debut, A.; Cumbal, L. Extracellular Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Amazonian Fruit Araza (Eugenia stipitata McVaugh). Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2016, 26, 2363–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamplecoskie, K.G.; Scaiano, J.C. Light Emitting Diode Irradiation Can Control the Morphology and Optical Properties of Silver Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1825–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzoubi, F.Y.; Ahmad, A.A.; Aljarrah, I.A.; Migdadi, A.B.; Al-Bataineh, Q.M. Localize Surface Plasmon Resonance of Silver Nanoparticles Using Mie Theory. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2023, 34, 2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravunni, G.K.; Kings, M.M.; Jeyabaskaran, A.; Sundararaj, A.S.; Divya, M.; Vijayakumar, S. Green Synthesis and Bioactivity of Peach Hibiscus Silver Nanoparticles. Sustain. Chem. One World 2025, 8, 100113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usta, C.; Saygi, K.O. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Corn Silk Extract and Its Antimutagenic Potential. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2025, 185, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.; Thimmappa, A.D.; Tomar, A.; Verma, A. Plant-Based Green Synthesis of AgNPs and Their Structural and Antimicrobial Characterization. Nat. Eng. Sci. 2025, 10, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocakaya, Z.; Dokan, F.K.; Karatoprak, G.Ş. Green Synthesis of Bioactive Nanocomposites Using Diploschistes scruposus Lichen and Investigation of Cytotoxic Effects on Cancer Cells. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 317, 129141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Yeap, S.P.; Che, H.X.; Low, S.C. Characterization of Magnetic Nanoparticle by Dynamic Light Scattering. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinnasamy, R.; Priyadharsan, A.; Kamaraj, C.; Manoharadas, S.; Manigandan, V.; Ahmed, M.; Ahmad, N. Phyto-Assisted Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles (Ag-NPs) Using Delonix elata Extract: Characterization, Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Photocatalytic Activities. Mol. Biotechnol. 2025, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, R.; Shetty, S.A.; Murugesan, G.; Varadavenkatesan, T.; Vinayagam, R. Sustainable Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Cynometra ramiflora Leaf Extract for Methyl Orange Degradation. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Kumari, P.; Mahto, S.K. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Momordica dioica Leaf Extract: Characterizing Antibacterial, Antibiofilm, and Catalytic Activities. Transit. Met. Chem. 2025, 50, 1151–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S. DLS and Zeta Potential—What They Are and What They Are Not? J. Control. Release 2016, 235, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Wahab, B.A.; Haque, A.; Alotaibi, H.F.; Alasiri, A.S.; Elnoubi, O.A.; Ahmad, M.Z.; Pathak, K.; Albarqi, H.A.; Walbi, I.A.; Wahab, S. Eco-Friendly Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Utilizing Olive Oil Waste By-Product and Their Incorporation into a Chitosan-Aloe Vera Gel Composite for Enhanced Wound Healing in Acid Burn Injuries. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2024, 165, 112587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, G.; Couto, R.; Oliveira, A.; Fontes, M.; Costa, L.; Barud, H.; Brighenti, F.L.; Constantino, V.R.L.; Perotti, G.F. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Mediated by Aqueous Açaí (Euterpe oleracea) Extracts. Eur. J. Acad. Res. 2022, X, 1164–1180. [Google Scholar]

- Borase, H.P.; Salunke, B.K.; Salunkhe, R.B.; Patil, C.D.; Hallsworth, J.E.; Kim, B.S.; Patil, S.V. Plant Extract: A Promising Biomatrix for Ecofriendly, Controlled Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2014, 173, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, P.D.; Mandavgane, S.A.; Kulkarni, B.D. Valorization of Pomegranate Peels: A Biorefinery Approach. Waste Biomass Valor. 2017, 8, 1127–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarov, V.V.; Love, A.J.; Sinitsyna, O.V.; Makarova, S.S.; Yaminsky, I.V.; E Taliansky, M.; O Kalinina, N. “Green” Nanotechnologies: Synthesis of Metal Nanoparticles Using Plants. Acta Naturae 2014, 6, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Oliveira, G.Z.S.; Lopes, C.A.P.; Sousa, M.H.; Silva, L.P. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Aqueous Extracts of Pterodon emarginatus Leaves Collected in the Summer and Winter Seasons. Int. Nano Lett. 2019, 9, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, Y.V.S.; Azevedo, M.M.R.; Felsemburgh, C.A.; de Souza, J.; Lima, A.K.O.; Braga, H.d.C.; Tada, D.B.; Gul, K.; Nakazato, G.; Taube, P.S. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles from Cumaru (Dipteryx odorata) Leaf Extract. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannon, J.C.; Kerry, J.P.; Cruz-Romero, M.; Azlin-Hasim, S.; Morris, M.; Cummins, E. Human Exposure Assessment of Silver and Copper Migrating from an Antimicrobial Nanocoated Packaging Material into an Acidic Food Simulant. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2016, 95, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rheder, D.T.; Guilger, M.; Bilesky-José, N.; Germano-Costa, T.; Pasquoto-Stigliani, T.; Gallep, T.B.B.; Grillo, R.; Carvalho, C.d.S.; Fraceto, L.F.; Lima, R. Synthesis of Biogenic Silver Nanoparticles Using Althaea officinalis as Reducing Agent: Evaluation of Toxicity and Ecotoxicity. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’ANnunziata, F.; Mosidze, E.; Folliero, V.; Lamparelli, E.P.; Lopardo, V.; Pagliano, P.; Della Porta, G.; Galdiero, M.; Bakuridze, A.D.; Franci, G. Eco-Friendly Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles from Peel and Juice of C. limon and Their Antiviral Efficacy against HSV-1 and SARS-CoV-2. Virus Res. 2024, 349, 199455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, C.M.; Naidoo, Y.; Dewir, Y.H.; Singh, M.; Daniels, A.N.; Lin, J. Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Tabernaemontana ventricosa Extracts. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangaram, S.; Naidoo, Y.; Dewir, Y.H.; Singh, M.; Lin, J.; Daniels, A.N.; Mendler-Drienyovszki, N. Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Barleria albostellata CB Clarke Leaves and Stems: Antibacterial and Cytotoxic Activity. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisa, A.J.T.; Josende, M.E.; Gelesky, M.A.; Ramos, D.F.; López, G.; Bernardi, F.; Monserrat, J.M. Açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles: Antimicrobial Efficacy and Ecotoxicological Assessment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 12005–12018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, S.S.; Cerqueira, M.Â.; Azevedo, A.G.; Pastrana, L.M.; Aouada, F.A.; Tanaka, F.C.; Perotti, G.F.; de Moura, M.R. Biotechnological Utilization of Amazonian Fruit: Development of Active Nanocomposites from Bacterial Cellulose and Silver Nanoparticles Based on Astrocaryum aculeatum (Tucumã) Extract. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, A.K.O.; Silveira, A.P.; Silva, R.C.; Machado, Y.A.A.; de Araújo, A.R.; Araujo, S.S.d.M.; Vieira, I.R.S.; Araújo, J.L.; dos Santos, L.C.; Rodrigues, K.A.d.F.; et al. Phytosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Guarana (Paullinia cupana Kunth) Leaf Extract Employing Different Routes: Characterization and Investigation of In Vitro Bioactivities. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2025, 15, 4301–4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, B.; Khatun, M.H.; Ahmed, F.; Ahmed, N.; Kadri, H.J.; Rasel, M.Z.U.; Saha, B.K.; Hakim, M.; Kabir, S.R.; Habib, M.R.; et al. Biosynthesis of Bixa orellana Seed Extract Mediated Silver Nanoparticles with Moderate Antioxidant, Antibacterial and Antiproliferative Activity. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 104675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Bharti, A.; Meena, V.K. Green Synthesis of Multi-Shaped Silver Nanoparticles: Optical, Morphological and Antibacterial Properties. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2015, 26, 3638–3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, S.; Asmare, M.M.; Khan, A.; Khan, T.; Ahmad, R.; Sunghwan, K.; Yun, S.-I. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Salvia rosmarinus Extract: Characterization, Mechanistic Antibacterial, Antibiofilm, and In Silico Evaluation. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 236, 122033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, Q.; Yao, B.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, A.; Sun, W.; Zhang, Q. Synthesis, Characterization and Evaluation of Cytotoxic Activity of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized by Chinese Herbal Cornus officinalis via Environment Friendly Approach. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017, 56, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elhamed, W.; Mohamed, A.A.; Saad, Z.H.; Hassanien, S.E.-S.I.; Salem, M.Z.M.; El-Hefny, M. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Mediated by Solanum nigrum Leaf Extract and Their Antifungal Activity against Pine Pathogens. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 35025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, L.H.G.; Neto, J.C.R.; Ribeiro, J.A.d.A.; Ricci-Silva, M.E.; Souza, M.T.; Rodrigues, C.M.; de Oliveira, A.E.; Abdelnur, P.V. Metabolomics Analysis of Oil Palm (Elaeis guineensis) Leaf: Evaluation of Sample Preparation Steps Using UHPLC–MS/MS. Metabolomics 2016, 12, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruttkies, C.; Schymanski, E.L.; Wolf, S.; Hollender, J.; Neumann, S. MetFrag Relaunched: Incorporating Strategies Beyond In Silico Fragmentation. J. Cheminform. 2016, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, J.S.; Torres, P.B.; Santos, D.Y.A.C.; Chow, F. Ensaio em Microplaca de Substâncias Redutoras pelo Método do Folin-Ciocalteu para Extratos de Algas. Inst. Biociências Univ. São Paulo 2017, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, J.; Torres, P.B.; Santos, D.Y.A.C.; Chow, F. Ensaio em Microplaca do Potencial Antioxidante Através do Método de Sequestro do Radical Livre DPPH para Extratos de Algas. Inst. Biociências Univ. São Paulo 2017, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, P.B.; Pires, J.S.; Santos, D.Y.A.C.; Chow, F. Ensaio do Potencial Antioxidante de Extratos de Algas Através do Sequestro do ABTS•+ em Microplaca. Inst. Biociências Univ. São Paulo 2017, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, T.d.C.; Sábio, R.M.; Luiz, M.T.; de Souza, L.C.; Fonseca-Santos, B.; da Silva, L.C.C.; Fantini, M.C.d.A.; Planeta, C.d.S.; Chorilli, M. Curcumin-Loaded Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles Dispersed in Thermo-Responsive Hydrogel as Potential Alzheimer Disease Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

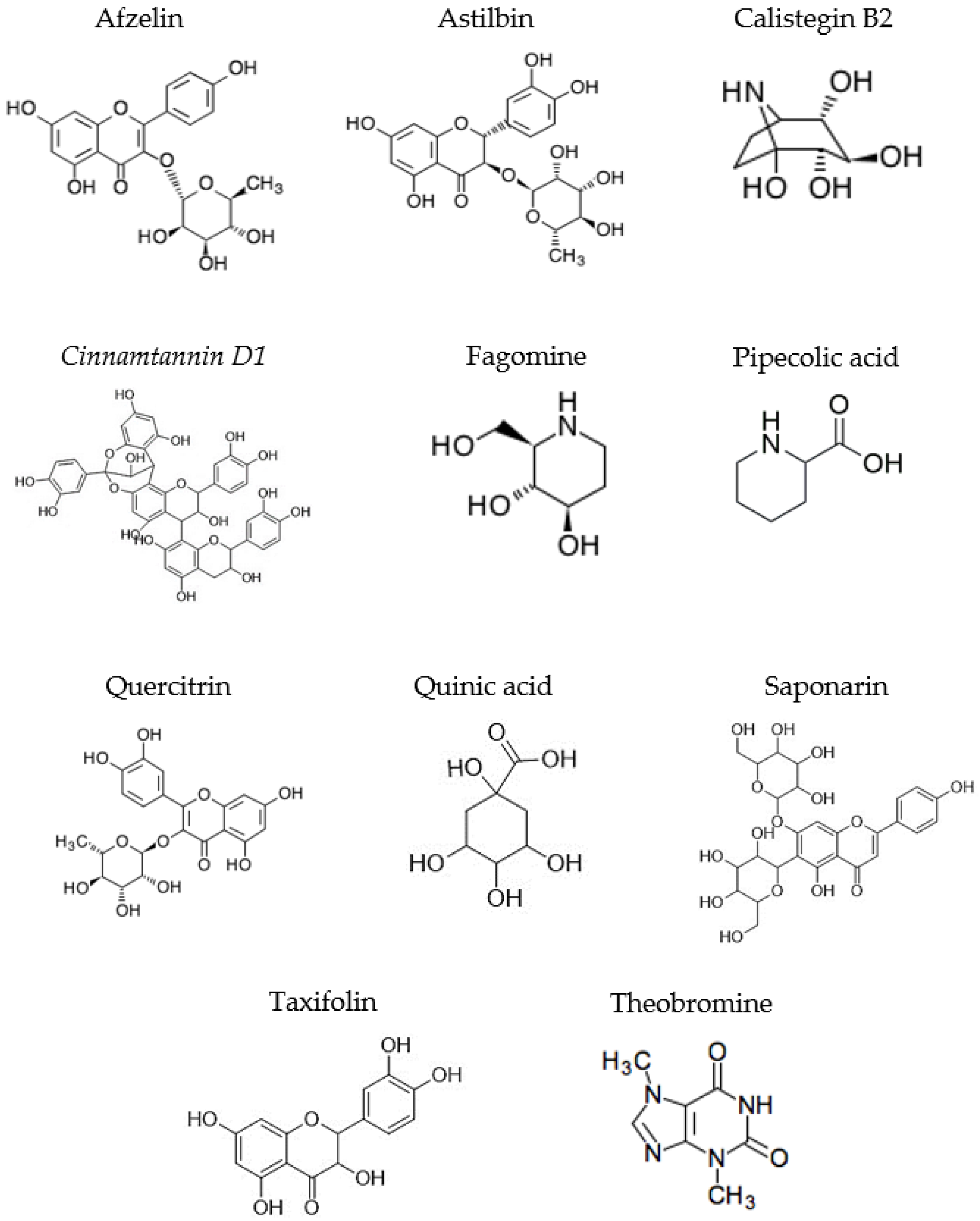

| POSITIVE MODE (+) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ext-A-LD | |||||

| Peak | TR (min) | m/z [M + H]+ | Molecular Formula | Compound Assigned | Class |

| 3 | 1.023 | 176.0915 | C7H13NO4 | Calistegin B2 | Nortropane alkaloid |

| 4 | 1.112 | 148.0973 | C6H13NO3 | Fagomine | Piperidine alkaloid |

| 8 | 8.697 | 181.0722 | C7H8N4O2 | Theobromine | Methyl xanthine alkaloid |

| Ext-A-LR | |||||

| 4 | 0.987 | 176.0915 | C7H13NO4 | Calistegin B2 | Nortropane alkaloid |

| 5 | 1.077 | 148.0970 | C6H13NO3 | Fagomine | Piperidine alkaloid |

| 8 | 7.953 | 181.0712 | C7H8N4O2 | Theobromine | Methyl xanthine alkaloid |

| 9 | 11.145 | 595.1652 | C27H30O15 | Flavone or flavonol derivative | Flavonoid glycosides |

| Ext-I-LD | |||||

| 3 | 0.986 | 176.0917 | C7H13NO4 | Calistegin B2 | Nortropane alkaloid |

| 7 | 1.548 | 130.0860 | C6H11NO2 | Pipecolic acid | Carboxylic acid from piperidine |

| 9 | 8.155 | 181.0722 | C7H8N4O2 | Theobromine | Methyl xanthine alkaloid |

| 11 | 11.774 | 595.1667 | C27H30O15 | Saponarin | Flavonoid glycosides |

| 12 | 12.155 | 865.1989 | C45H36O18 | Cinnamtannin D1 | Proanthocyanidin |

| 13 | 14.525 | 451.1241 | C21H22O11 | Astilbin | Flavonoid glycosides |

| 13 | 14.525 | 305.0656 | C15H12O7 | Taxifolin | Dihyroflavonols |

| 14 | 15.096 | 303.0501 | C15H10O7 | Flavone or flavonol derivative | Flavones/Flavonols |

| Ext-I-LR | |||||

| 5 | 0.994 | 176.0916 | C7H13NO4 | Calistegin B2 | Nortropane alkaloid |

| 6 | 1.072 | 148.0973 | C6H13NO3 | Fagomine | Piperidine alkaloid |

| 13 | 11.159 | 291.0846 595.1638 | C15H14O6 | Flavone or flavonol derivative | Flavanols |

| 14 | 11.503 | 865.1946 | C45H36O18 | Cinnamtannin D1 | Proanthocyanidin |

| NEGATIVE MODE (−) | |||||

| Peak | TR (min) | m/z [M + H]− | Molecular Formula | Compound | Class |

| Ext-A-LR | |||||

| 7 | 13.496 | 449.1074 | C21H22O11 | Astilbin | Flavonoid glycosides |

| 8 | 14.320 | 447.0917 | C21H20O11 | Quercitrin | Flavonoid glycosides |

| 10 | 15.262 | 431.0967 | C21H20O10 | Afzelin | Flavonoid glycosides |

| Ext-I-LD | |||||

| 7 | 1.230 | 191.0563 | C7H12O6 | Quinic acid | Cyclic polyol |

| 10 | 14.289 | 449.1104 | C21H22O11 | Astilbin | Flavonoid glycosides |

| 12 | 14.870 | 447.0939 | C21H20O11 | Quercitrin | Flavonoid glycosides |

| Ext-I-LR | |||||

| 9 | 11.101 | 289.0713 | C15H14O6 | Flavone or flavonol derivative | Flavanols |

| 12 | 13.529 | 449.1097 | C21H22O11 | Astilbin | Flavonoid glycosides |

| 14 | 14.097 | 449.1087 | C21H22O11 | Chalcone derivative | Chalcones |

| 15 | 14.333 | 447.0936 | C21H20O11 | Quercitrin | Flavonoid glycosides |

| 17 | 15.266 | 431.0983 | C21H20O10 | Afzelin | Flavonoid glycosides |

| Samples of Extracts | TPC (µg GAE/g) | DPPH (µg GAE/g) | ABTS (µg GAE/g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ext-A-LD | 120.50 ± 0.04 d | 23.43 ± 0.06 b | 13.80 ± 0.03 b |

| Ext-I-LD | 203.50 ± 0.06 c | 34.38 ± 0.05 a | 17.60 ± 0.03 a |

| Ext-A-LR | 237.00 ± 0.05 b | 29.48 ± 0.04 ab | 15.21 ± 0.05 b |

| Ext-I-LR | 281.40 ± 0.04 a | 31.11 ± 0.04 ab | 17.75 ± 0.02 a |

| Samples | Diameter (nm) | Concentration (Particles/mL) | Span Index |

|---|---|---|---|

| AgNPs-A-LD | 96.6 ± 5.2 | 3.71 × 1010 | 0.863 |

| AgNPs-I-LD | 60.8 ± 0.9 | 6.46 × 107 | 0.591 |

| AgNPs-A-LR | 77.6 ± 2.1 | 8.60 × 107 | 1.014 |

| AgNPs-I-LR | 39.4 ± 16.1 | 3.89 × 109 | 0.342 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lima, A.K.O.; Oliveira, T.P.d.S.; Florêncio, I.; Tavares Junior, A.G.; Araújo, V.H.S.; Vasconcelos, A.A.; Chorilli, M.; Braga, H.d.C.; Tada, D.B.; Nakazato, G.; et al. Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles from Paullinia cupana Kunth Leaf: Effect of Seasonality and Preparation Method of Aqueous Extracts. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010072

Lima AKO, Oliveira TPdS, Florêncio I, Tavares Junior AG, Araújo VHS, Vasconcelos AA, Chorilli M, Braga HdC, Tada DB, Nakazato G, et al. Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles from Paullinia cupana Kunth Leaf: Effect of Seasonality and Preparation Method of Aqueous Extracts. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010072

Chicago/Turabian StyleLima, Alan Kelbis Oliveira, Tainá Pereira da Silva Oliveira, Isadora Florêncio, Alberto Gomes Tavares Junior, Victor Hugo Sousa Araújo, Arthur Abinader Vasconcelos, Marlus Chorilli, Hugo de Campos Braga, Dayane Batista Tada, Gerson Nakazato, and et al. 2026. "Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles from Paullinia cupana Kunth Leaf: Effect of Seasonality and Preparation Method of Aqueous Extracts" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010072

APA StyleLima, A. K. O., Oliveira, T. P. d. S., Florêncio, I., Tavares Junior, A. G., Araújo, V. H. S., Vasconcelos, A. A., Chorilli, M., Braga, H. d. C., Tada, D. B., Nakazato, G., Báo, S. N., Taube, P. S., Ribeiro, J. A. d. A., Rodrigues, C. M., & Garcia, M. P. (2026). Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles from Paullinia cupana Kunth Leaf: Effect of Seasonality and Preparation Method of Aqueous Extracts. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010072