Development and Application of an LC-MS/MS Method for Simultaneous Quantification of Azathioprine and Its Metabolites: Pharmacokinetic and Microbial Metabolism Study of a Colon-Targeted Nanoparticle

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. LC-MS/MS Optimization

2.2. Method Validation

2.2.1. Selectivity and Specificity

2.2.2. Calibration Curve and Range

2.2.3. Accuracy and Precision

2.2.4. Carry-Over Effect

2.2.5. Recovery and Matrix Effect

2.2.6. Dilution Integrity

2.2.7. Stability

2.2.8. Method Comparison

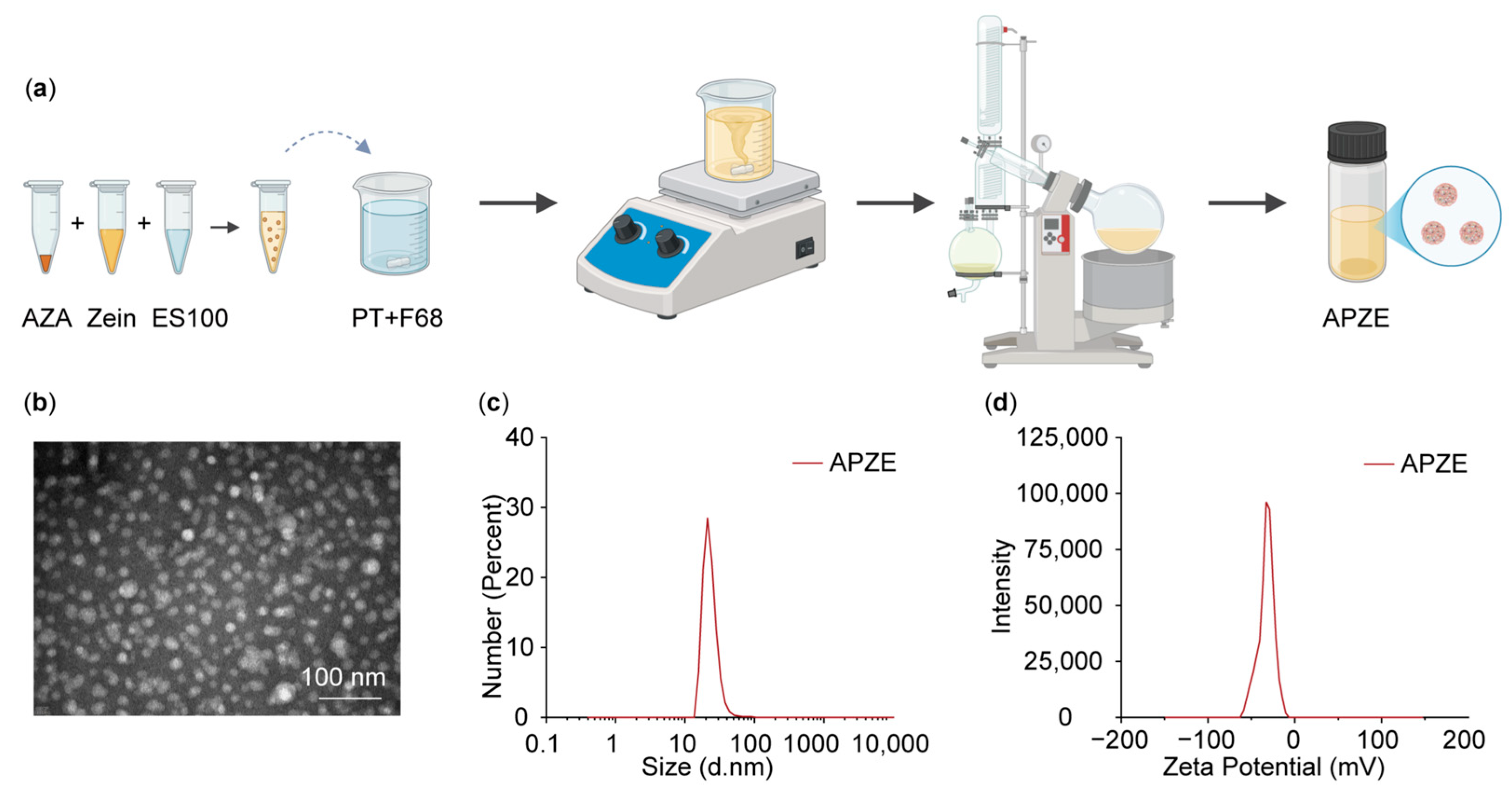

2.3. Preparation and Characterization of Nanoparticles

2.4. Pharmacokinetic Analysis

2.5. Microbial Metabolism

2.6. Limitations and Future Perspectives

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Reagents

3.2. Instrumentation

3.3. LC-MS/MS Analytical Conditions

3.4. Preparation of Solutions and Samples

3.5. Sample Preparation

3.6. Method Validation

3.6.1. Selectivity and Specificity

3.6.2. Calibration Curve and Range

3.6.3. Accuracy and Precision

3.6.4. Carry-Over Effect

3.6.5. Recovery and Matrix Effect

3.6.6. Dilution Integrity

3.6.7. Stability

3.7. Preparation and Characterization of Nanoparticles

3.8. Pharmacokinetic Analysis

3.9. Microbial Metabolism

3.10. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AZA | Azathioprine |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry |

| 6-MP | 6-Mercaptopurine |

| 6-MMP | 6-Methylmercaptopurine |

| 6-TG | 6-Thioguanine |

| 6-TU | 6-Thiouric acid |

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| PT | Pectin |

| ES100 | Eudragit®S100 |

| GST | Glutathione S-transferase |

| TPMT | Thiopurine methyltransferase |

| XO | Xanthine oxidase |

| HPRT | Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase |

| TIMP | Thioinosine monophosphate |

| 6-TGNs | 6-Thioguanine nucleotides |

| HPLC-UV | High-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection |

| PP | Protein precipitation |

| SPE | Solid-phase extraction |

| LLE | Liquid–liquid extraction |

| UHPLC-MS/MS | Ultra high performance LC-MS/MS |

| ESI | Electrospray ionization |

| IS | Internal standard |

| MRM | Multiple reaction monitoring |

| DP | Declustering potential |

| EP | Entrance potential |

| CE | Collision energy |

| CXP | Collision cell exit potential |

| LLOQ | Lower limit of quantitation |

| S/N | Signal-to-noise |

| r | Correlation coefficients |

| QC | Quality control |

| ULOQ | Upper limit of quantification |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| RBC | Red blood cells |

| PDI | Polydispersity index |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| Tmax | Peak time |

| Cmax | Peak concentration |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

References

- Cai, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, J. Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 765474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinisch, W.; Angelberger, S.; Petritsch, W.; Shonova, O.; Lukas, M.; Bar-Meir, S.; Teml, A.; Schaeffeler, E.; Schwab, M.; Dilger, K.; et al. Azathioprine versus mesalazine for prevention of postoperative clinical recurrence in patients with Crohn’s disease with endoscopic recurrence: Efficacy and safety results of a randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, multicentre trial. Gut 2010, 59, 752–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yewale, R.V.; Ramakrishna, B.S.; Doraisamy, B.V.; Basumani, P.; Venkataraman, J.; Jayaraman, K.; Murali, A.; Premkumar, K.; Kumar, A.S. Long-term safety and effectiveness of azathioprine in the management of inflammatory bowel disease: A real-world experience. JGH Open 2023, 7, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Wu, G.D.; Albenberg, L.; Tomov, V.T. Gut microbiota and IBD: Causation or correlation? Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Feng, W.; Chen, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, G.; Xia, L.; Wu, K. Intestinal microecology dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel disease: Pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. Innov. Med. 2024, 2, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadegar, A.; Bar-Yoseph, H.; Monaghan, T.M.; Pakpour, S.; Severino, A.; Kuijper, E.J.; Smits, W.K.; Terveer, E.M.; Neupane, S.; Nabavi-Rad, A.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation: Current challenges and future landscapes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2024, 37, e0006022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; He, Y.; Yang, X.; Nie, Y.; Sun, L. Crosstalk between gut microbiota and gut resident macrophages in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Transl. Intern. Med. 2023, 11, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagnini, C.; Gori, M.; Di Paolo, M.C.; Urgesi, R.; Cicione, C.; Zingariello, M.; Arciprete, F.; Velardi, V.; Viciani, E.; Padella, A.; et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG Administration Is Associated with Stimulation of Vitamin D/VDR Pathway and Mucosal Microbiota Modulation in Ulcerative Colitis Patients: A Pilot Study. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Fan, J.; Huang, H.; Deng, J.; Tan, B. Potential mechanisms of different methylation degrees of pectin driving intestinal microbiota and their metabolites to modulate intestinal health of Micropterus salmoides. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 251, 126297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Pierce, A.F.; Wagner, W.L.; Khalil, H.A.; Chen, Z.; Funaya, C.; Ackermann, M.; Mentzer, S.J. Biomaterial-Assisted Anastomotic Healing: Serosal Adhesion of Pectin Films. Polymers 2021, 13, 2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; An, D.; Li, J.; Deng, S. Zein-based nanoparticles: Preparation, characterization, and pharmaceutical application. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1120251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotagale, N.; Maniyar, M.; Somvanshi, S.; Umekar, M.; Patel, C.J. Eudragit-S, Eudragit-L and cellulose acetate phthalate coated polysaccharide tablets for colonic targeted delivery of azathioprine. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2010, 15, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocco, G.; Pelin, M.; Franca, R.; De Iudicibus, S.; Cuzzoni, E.; Favretto, D.; Martelossi, S.; Ventura, A.; Decorti, G. Pharmacogenetics of azathioprine in inflammatory bowel disease: A role for glutathione-S-transferase? World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 3534–3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udomkarnjananun, S.; Francke, M.I.; De Winter, B.C.M.; Mulder, M.B.; Baan, C.C.; Metselaar, H.J.; den Hoed, C.M.; Hesselink, D.A. Therapeutic drug monitoring of immunosuppressive drugs in hepatology and gastroenterology. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2021, 54–55, 101756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlovska, K.; Petrushevska, M.; Gjorgjievska, K.; Zendelovska, D.; Ribarska, J.T.; Kikerkov, I.; Gjatovska, L.L.; Atanasovska, E. Importance of 6-Thioguanine Nucleotide Metabolite Monitoring in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients Treated with Azathioprine. Prilozi 2019, 40, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearry, R.B.; Barclay, M.L. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine pharmacogenetics and metabolite monitoring in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2005, 20, 1149–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, B.A.; Rawsthorne, P.; Bernstein, C.N. The utility of 6-thioguanine metabolite levels in managing patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2004, 99, 1744–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawwa, A.F.; Millership, J.S.; Collier, P.S.; McElnay, J.C. Development and validation of an HPLC method for the rapid and simultaneous determination of 6-mercaptopurine and four of its metabolites in plasma and red blood cells. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2009, 49, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, A.C.; Barroso, L.H.F.; Mourao-Junior, C.A.; Chebli, J.M.F.; Nascimento, J.W.L. Simultaneous Monitoring of Azathioprine Metabolites in Erythrocytes of Crohn’s Disease Patients by HPLC-UV. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2022, 60, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Li, D.; Xiang, D.; Li, X.; Liu, L.; Liu, D.; Gong, X. Development and validation of a novel HPLC-UV method for simultaneous determination of azathioprine metabolites in human red blood cells. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, M.J.; Raja Kavitha, J.; Kumar, K.P.; Sivakumar, T. Simultaneous determination of azathioprine and its metabolite 6-mercaptopurine in human plasma using solid phase extraction-evaporation and liquid chromatography–positive electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Int. Curr. Pharm. J. 2012, 1, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghobashy, M.A.; Hassan, S.A.; Abdelaziz, D.H.; Elhosseiny, N.M.; Sabry, N.A.; Attia, A.S.; El-Sayed, M.H. Development and validation of LC-MS/MS assay for the simultaneous determination of methotrexate, 6-mercaptopurine and its active metabolite 6-thioguanine in plasma of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Correlation with genetic polymorphism. J. Chromatogr. B 2016, 1038, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attallah, O.A.; Al-Ghobashy, M.A.; Ayoub, A.T.; Nebsen, M. Magnetic molecularly imprinted polymer nanoparticles for simultaneous extraction and determination of 6-mercaptopurine and its active metabolite thioguanine in human plasma. J. Chromatogr. A 2018, 1561, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiwattanakul, S.; Prommas, S.; Jenjirattithigarn, N.; Santon, S.; Puangpetch, A.; Pakakasama, S.; Anurathapan, U.; Sukasem, C. Development and validation of a reliable method for thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) enzyme activity in human whole blood by LC-MS/MS: An application for phenotypic and genotypic correlations. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2017, 145, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsous, M.M.; Hawwa, A.F.; McElnay, J.C. Determination of azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine metabolites in dried blood spots: Correlation with RBC concentrations. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2020, 178, 112870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Mei, S.; Xu, J.; Zhang, D.; Jin, S.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, L. Simultaneous UPLC-MS/MS Determination of 6-mercaptopurine, 6-methylmercaptopurine and 6-thioguanine in Plasma: Application to the Pharmacokinetic Evaluation of Novel Dosage forms in Beagle Dogs. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020, 26, 6013–6020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guba, A.; Kováts, P.; Mezei, Z.A.; Papp, M.; Csősz, É.; Kalló, G. Analysis of Azathioprine Metabolites in Autoimmune Hepatitis Patient Blood-Method Development and Validation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Atkinson, N.; Crews, K.R.; Molinelli, A.R. Quantification of Thiopurine Metabolites in Human Erythrocytes by Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Methods Mol. Biol. 2024, 2737, 443–452. [Google Scholar]

- Moein, M.M.; El Beqqali, A.; Abdel-Rehim, M. Bioanalytical method development and validation: Critical concepts and strategies. J. Chromatogr. B 2017, 1043, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampič, K.; Trontelj, J.; Prosen, H.; Drobne, D.; Šmid, A.; Vovk, T. Determination of 6-thioguanine and 6-methylmercaptopurine in dried blood spots using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry: Method development, validation and clinical application. Clin. Chim. Acta 2019, 499, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Li, W.; Picard, F. Assessment of matrix effect in quantitative LC-MS bioanalysis. Bioanalysis 2024, 16, 631–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.; Nayi, S.; Khunt, D.; Kapoor, D.U.; Salave, S.; Prajapati, B.; Vora, C.; Malviya, R.; Maheshwari, R.; Patel, R. Zein: Potential biopolymer in inflammatory bowel diseases. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2025, 113, e37785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. M10 Bioanalytical Method Validation and Study Sample Analysis: Guidance for Industry. 2022. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/162903/download (accessed on 26 November 2025).

| Analytes | Precursor Ion (amu) | Product Ion (amu) | DP (V) | EP (V) | CE (V) | CXP (V) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AZA | 277.92 | 141.93 | 75 | 8 | 15 | 15 |

| 6-MP | 153.00 | 118.90 | 120 | 10 | 28 | 15 |

| 6-MMP | 167.00 | 125.90 | 120 | 8 | 28 | 15 |

| 6-TG | 168.00 | 134.00 | 120 | 8 | 28 | 15 |

| 6-TU | 182.94 | 106.00 | −120 | −10 | −28 | −12 |

| 6-MP-13C,15N2 | 156.20 | 121.90 | 120 | 8 | 30 | 15 |

| 6-MMP-D3 | 170.10 | 151.90 | 120 | 8 | 31 | 15 |

| 6-TU-13C3 | 185.95 | 142.88 | −110 | −10 | −21.5 | −15 |

| Analytes | Nominal Concentration (ng/mL) | Intra-Day (n = 6) | Inter-Day (3 Days, n = 6) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured Concentration (ng/mL) | Accuracy (%) | Precision (CV, %) | Measured Concentration (ng/mL) | Accuracy (%) | Precision (CV, %) | ||

| AZA | 5 | 4.74 ± 0.17 | 94.80 | 3.59 | 4.75 ± 0.23 | 95.00 | 4.84 |

| 15 | 14.40 ± 0.49 | 96.00 | 3.40 | 14.07 ± 0.59 | 93.80 | 4.19 | |

| 75 | 73.57 ± 1.10 | 98.09 | 1.50 | 74.16 ± 2.09 | 98.88 | 2.82 | |

| 750 | 734.17 ± 25.27 | 97.89 | 3.44 | 731.94 ± 22.28 | 97.59 | 3.04 | |

| 6-MP | 5 | 4.91 ± 0.11 | 98.20 | 2.24 | 4.97 ± 0.20 | 99.40 | 4.02 |

| 15 | 13.90 ± 0.52 | 92.67 | 3.74 | 14.18 ± 0.56 | 94.53 | 3.95 | |

| 75 | 71.17 ± 3.66 | 94.89 | 5.14 | 73.73 ± 4.12 | 98.31 | 5.59 | |

| 750 | 754.33 ± 16.66 | 100.58 | 2.21 | 739.50 ± 23.32 | 98.60 | 3.15 | |

| 6-MMP | 5 | 4.77 ± 0.18 | 95.40 | 3.77 | 4.86 ± 0.24 | 97.20 | 4.94 |

| 15 | 14.68 ± 0.29 | 97.87 | 1.98 | 14.72 ± 0.33 | 98.13 | 2.24 | |

| 75 | 76.93 ± 2.01 | 102.57 | 2.61 | 75.97 ± 1.62 | 101.29 | 2.13 | |

| 750 | 727.00 ± 25.53 | 96.93 | 3.51 | 739.83 ± 18.22 | 98.64 | 2.46 | |

| 6-TG | 5 | 5.02 ± 0.20 | 100.40 | 3.98 | 4.94 ± 0.26 | 98.80 | 5.26 |

| 15 | 14.40 ± 0.68 | 96.00 | 4.72 | 13.96 ± 0.85 | 93.07 | 6.09 | |

| 75 | 74.38 ± 4.77 | 99.17 | 6.41 | 71.18 ± 4.51 | 94.91 | 6.34 | |

| 750 | 782.33 ± 56.32 | 104.31 | 7.20 | 769.61 ± 34.75 | 102.61 | 4.52 | |

| 6-TU | 5 | 4.95 ± 0.44 | 99.00 | 8.89 | 4.95 ± 0.34 | 99.00 | 6.87 |

| 15 | 14.05 ± 0.71 | 93.67 | 5.05 | 14.62 ± 0.85 | 97.47 | 5.81 | |

| 75 | 75.97 ± 4.78 | 101.29 | 6.29 | 75.14 ± 3.95 | 100.19 | 5.26 | |

| 750 | 751.00 ± 36.17 | 100.13 | 4.82 | 766.28 ± 45.64 | 102.17 | 5.96 | |

| Analytes | Nominal Concentration (ng/mL) | IS Normalized Recovery (%) | CV of IS Normalized Recovery (%) | IS Normalized Matrix Factor (%) | CV of IS Normalized Matrix Factor (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AZA | 15 | 98.04 ± 4.62 | 4.71 | 91.54 ± 2.79 | 3.05 |

| 75 | 96.26 ± 5.33 | 5.54 | 93.06 ± 4.81 | 5.17 | |

| 750 | 92.83 ± 5.84 | 6.29 | 96.59 ± 5.55 | 5.75 | |

| 6-MP | 15 | 98.08 ± 8.99 | 9.17 | 93.64 ± 3.94 | 4.21 |

| 75 | 92.39 ± 4.64 | 5.02 | 92.18 ± 5.76 | 6.25 | |

| 750 | 95.93 ± 5.11 | 5.33 | 94.60 ± 6.05 | 6.40 | |

| 6-MMP | 15 | 96.68 ± 6.65 | 6.88 | 91.84 ± 7.50 | 8.17 |

| 75 | 94.52 ± 7.41 | 7.84 | 95.91 ± 3.04 | 3.17 | |

| 750 | 96.57 ± 5.12 | 5.30 | 93.27 ± 4.91 | 5.26 | |

| 6-TG | 15 | 97.16 ± 4.03 | 4.15 | 92.58 ± 6.32 | 6.83 |

| 75 | 92.38 ± 6.94 | 7.51 | 94.95 ± 4.77 | 5.02 | |

| 750 | 93.85 ± 7.88 | 8.40 | 94.83 ± 6.33 | 6.68 | |

| 6-TU | 15 | 95.27 ± 3.90 | 4.09 | 96.71 ± 5.32 | 5.50 |

| 75 | 94.46 ± 5.28 | 5.59 | 94.88 ± 3.87 | 4.08 | |

| 750 | 93.95 ± 6.17 | 6.57 | 94.25 ± 5.53 | 5.87 |

| Analytes | Nominal Concentration (ng/mL) | Measured Concentration (ng/mL) | Accuracy (%) | Precision (CV, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AZA | 50 | 50.23 ± 1.02 | 100.46 | 2.03 |

| 500 | 489.67 ± 12.29 | 97.93 | 2.51 | |

| 6-MP | 50 | 48.02 ± 1.76 | 96.04 | 3.67 |

| 500 | 472.00 ± 14.13 | 94.40 | 2.99 | |

| 6-MMP | 50 | 50.67 ± 2.39 | 101.34 | 4.72 |

| 500 | 483.00 ± 20.05 | 96.60 | 4.15 | |

| 6-TG | 50 | 49.42 ± 3.26 | 98.84 | 6.60 |

| 500 | 479.17 ± 23.57 | 95.83 | 4.92 | |

| 6-TU | 50 | 49.35 ± 2.04 | 98.70 | 4.13 |

| 500 | 481.33 ± 35.17 | 96.27 | 7.31 |

| Reference | Sample Matrix | Sample Volume | Analytical Methods | Sample Preparation | Analytical Run Time | Analytes | Analytical Linear Range | Recovery (%) | Matrix Effect (CV, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [18] | Plasma | 200 µL | HPLC-UV | Protein precipitation (PP, perchloric acid) | 13 min | 6-MP | 10–200 ng/mL | 96.5–99.5 | - |

| 6-MMP | 100–2000 ng/mL | 103.3–106.5 | |||||||

| 6-TG | 10–1250 ng/mL | 93.3–95.6 | |||||||

| 6-TU | 20–1350 ng/mL | 91.2–93.4 | |||||||

| Red blood cells (RBC) | 6-MP | 10–200 pmol/8 × 108 RBC | 89.9–92.6 | ||||||

| 6-MMP | 250–24,000 pmol/8 × 108 RBC | 98.3–102.4 | |||||||

| 6-TG | 30–1500 pmol/8 × 108 RBC | 76.4–76.9 | |||||||

| 6-TU | 50–1500 pmol/8 × 108 RBC | 29.3–33.5 | |||||||

| [19] | RBC | 200 µL | HPLC-UV | PP (perchloric acid) | 31 min | 6-MMP | 147–4906 pmol/8 × 108 RBC | 91.9 | - |

| [20] | RBC | 100 µL | HPLC-UV | PP (perchloric acid) | 5.5 min | 6-MMP | 166.2–16,620 ng/mL | 94.6–96.4 | - |

| 6-TG | 25.1–2508 ng/mL | 53.7–54.2 | |||||||

| [22] | Plasma | 1 mL | UHPLC-MS/MS | Solid-phase extraction (SPE) | 1.4 min | 6-MP | 6.25–200 ng/mL | 94.30–104.41 | 99.11–104.99 |

| 6-TG | 95.99–101.54 | 98.03–105.38 | |||||||

| [25] | Dried blood spot | 15 μL (original volume) | UHPLC-MS/MS | SPE (perchloric acid) | 10 min | 6-MMP | 623.3–29,085 ng/mL | - | - |

| 6-TG | 83.6–2508 ng/mL | ||||||||

| [23] | Plasma | 1 mL | UHPLC-MS/MS | MMI-SPE | 2 min | 6-MP | - | 88.89–103.03 | 89.09–96.06 |

| 6-TG | 85.94–98.27 | 88.94–92.63 | |||||||

| [26] | Plasma | 100 µL | UHPLC-MS/MS | PP | 4 min | 6-MP | 5–500 ng/mL | 92.02–97.02 | 119.52–123.35 |

| 6-MMP | 95.64–99.92 | 104.34–108.37 | |||||||

| 6-TG | 84.62–88.27 | 121.14–129.10 | |||||||

| [27] | Whole blood | 200 µL | UHPLC-MS/MS | PP | 4 min | 6-MMP | 5–1250 ng/mL | 87.75–106.78 | 111.42–114.88 |

| 6-TG | 86.18–100.24 | 101.89–114.94 | |||||||

| [28] | RBC | 50 µL | UHPLC-MS/MS | PP (perchloric acid) | 2.5 min | 6-MMP | 166.2–33,240 ng/mL | 97 | 99 |

| 6-TG | 33.4–4180 ng/mL | 89 | 111 | ||||||

| [21] | Plasma | 500 µL | HPLC-MS/MS | SPE-Evaporation | 2 min | AZA | 2.455–106.568 ng/mL | 98.22–100.23 | - |

| 6-MP | 1.165–101.143 ng/mL | 99.48–100.63 | - | ||||||

| [24] | Whole blood | 100 µL | HPLC-MS/MS | LLE | 7 min | 6-MMP | 2.5–360 ng/mL | 85.3–92.74 | 90.00–92.43 |

| [30] | Dried blood spot | 30 μL (original volume) | HPLC-MS/MS | PP (perchloric acid) | 20 min | 6-MMP | 400–8000 ng/mL | 87.5–103.1 | 92.2–102.1 |

| 6-TG | 80–8000 ng/mL | 79.7–89.0 | 102.7–104.5 | ||||||

| This study | Plasma | 100 µL | HPLC-MS/MS | One-step PP | 5.5 min | AZA | 5–1000 ng/mL | 92.83–98.04 | 91.54–96.59 |

| 6-MP | 92.39–98.08 | 92.18–94.60 | |||||||

| 6-MMP | 94.52–96.68 | 91.84–95.91 | |||||||

| 6-TG | 92.38–97.16 | 92.58–94.95 | |||||||

| 6-TU | 93.95–95.27 | 94.25–96.71 |

| Analyte | Preparation | Tmax (h) | Cmax (ng/mL) | AUC (ng·h/mL) | T1/2 (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AZA | AZAS | 0.50 ± 0.00 | 474.13 ± 117.07 | 705.37 ± 148.62 | 2.26 ± 2.43 |

| APZE | 0.50 ± 0.00 | 667.63 ± 166.44 * | 783.99 ± 79.87 | 2.16 ± 1.26 | |

| 6-MP | AZAS | 0.56 ± 0.18 | 30.88 ± 12.26 | 52.74 ± 16.72 | 0.72 ± 0.38 |

| APZE | 0.50 ± 0.00 | 88.55 ± 59.46 ** | 101.95 ± 53.97 ** | 0.70 ± 0.19 | |

| 6-MMP | AZAS | 2.38 ± 0.92 | 33.13 ± 14.27 | 239.54 ± 77.48 | 4.56 ± 0.68 |

| APZE | 2.13 ± 0.83 | 36.94 ± 5.01 | 271.42 ± 74.88 | 4.97 ± 1.56 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Han, J.; Sun, N.; Zhu, Y.; Mei, D.; Zhao, L. Development and Application of an LC-MS/MS Method for Simultaneous Quantification of Azathioprine and Its Metabolites: Pharmacokinetic and Microbial Metabolism Study of a Colon-Targeted Nanoparticle. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010058

Zhang J, Han J, Sun N, Zhu Y, Mei D, Zhao L. Development and Application of an LC-MS/MS Method for Simultaneous Quantification of Azathioprine and Its Metabolites: Pharmacokinetic and Microbial Metabolism Study of a Colon-Targeted Nanoparticle. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010058

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jingjing, Jiaqi Han, Ning Sun, Yuhan Zhu, Dong Mei, and Libo Zhao. 2026. "Development and Application of an LC-MS/MS Method for Simultaneous Quantification of Azathioprine and Its Metabolites: Pharmacokinetic and Microbial Metabolism Study of a Colon-Targeted Nanoparticle" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010058

APA StyleZhang, J., Han, J., Sun, N., Zhu, Y., Mei, D., & Zhao, L. (2026). Development and Application of an LC-MS/MS Method for Simultaneous Quantification of Azathioprine and Its Metabolites: Pharmacokinetic and Microbial Metabolism Study of a Colon-Targeted Nanoparticle. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010058