Ligustilide: A Phytochemical with Potential in Combating Cancer Development and Progression—A Comprehensive and Critical Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

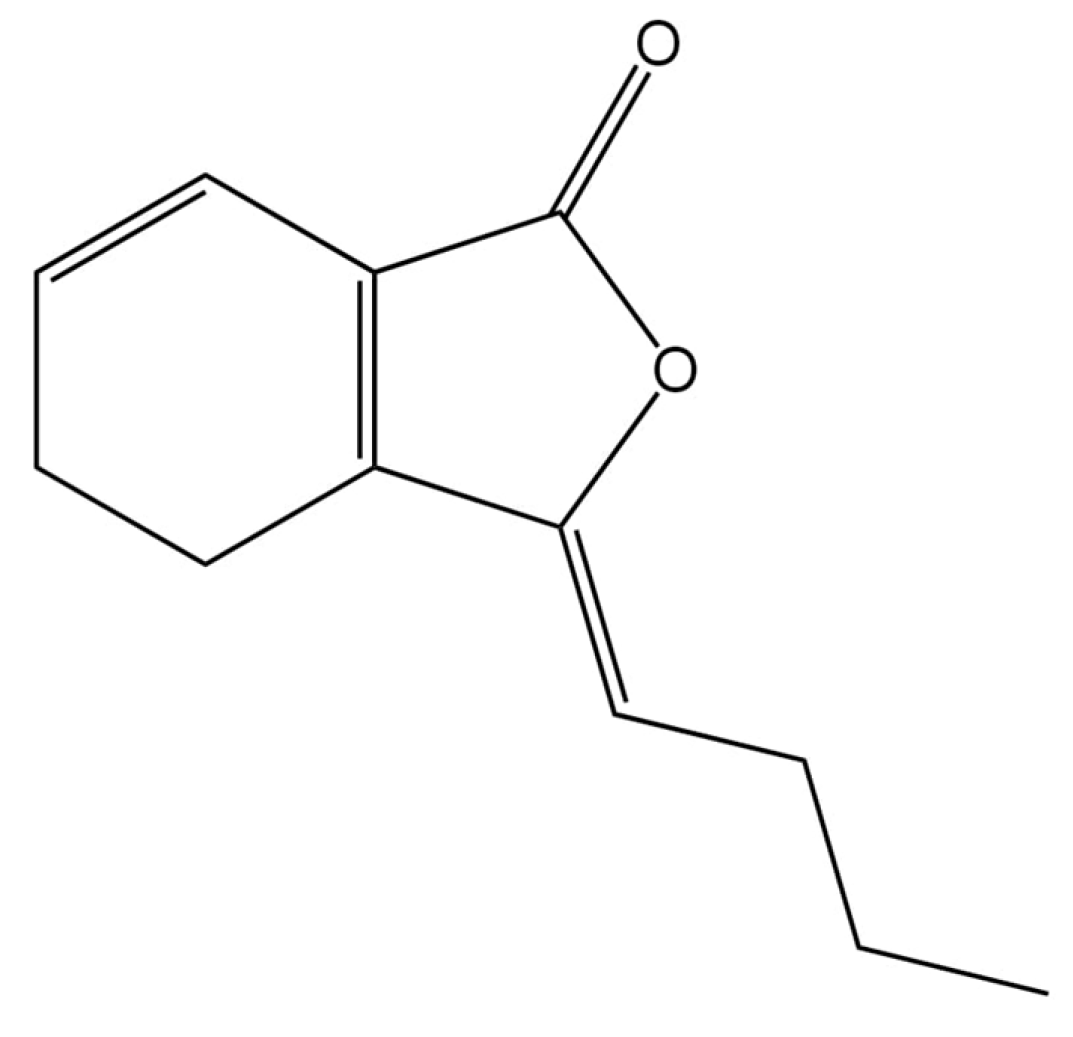

2. Ligustilide: Unveiling Its Biosynthesis, Physicochemical Properties, and Pharmacokinetics

2.1. Biosynthesis of Ligustilide: Pathways and Regulatory Mechanisms

2.2. Physicochemical Properties of Ligustilide: Structural Characteristics and Stability

2.3. Pharmacokinetics of Ligustilide: Evaluating the Phytochemical’s Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Toxicity

2.4. Additional Considerations: Metabolism, Plasma Stability, Tissue Distribution, and Strategies to Improve Bioavailability

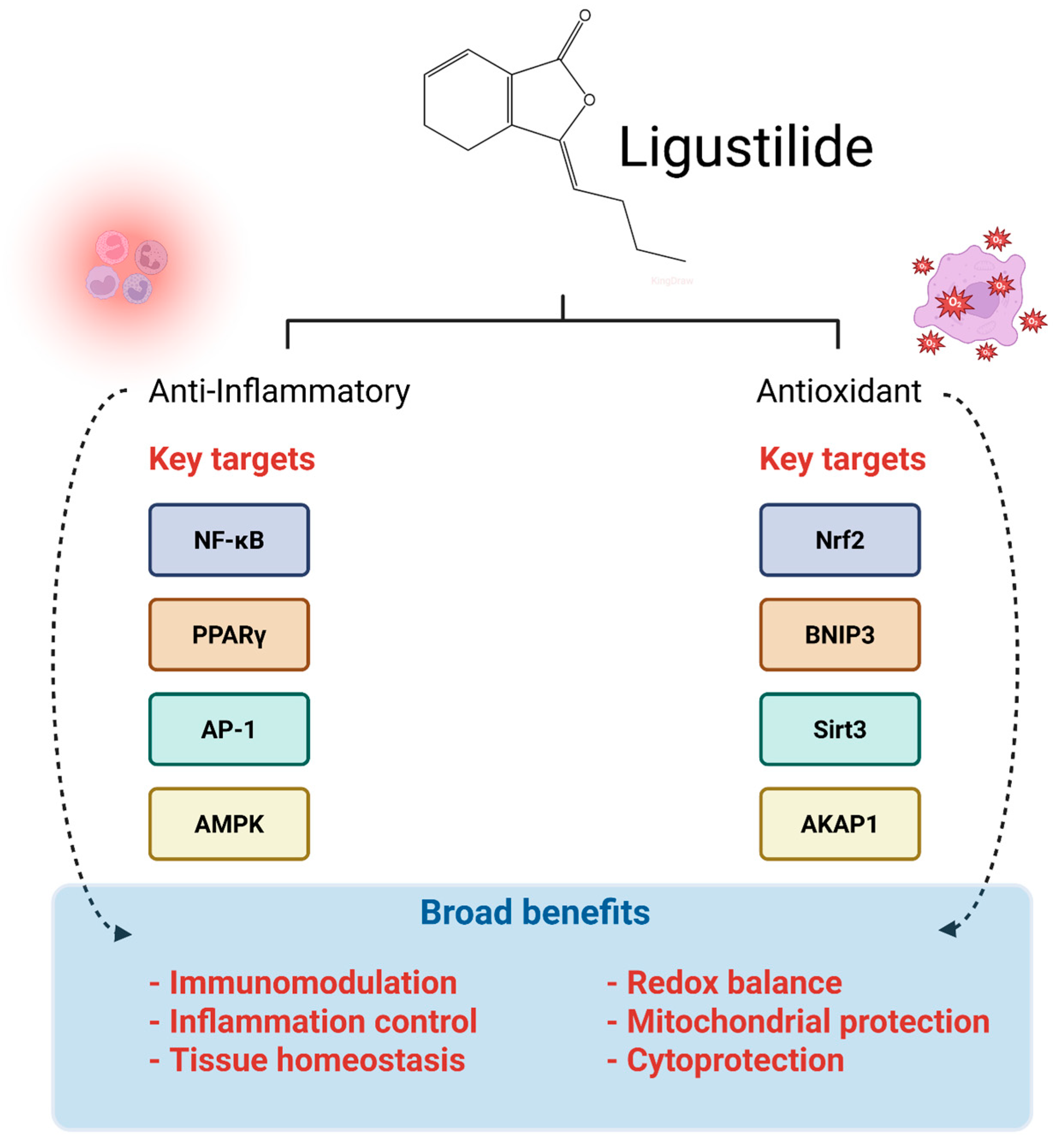

3. Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Pharmacodynamics of Ligustilide: Mechanisms of Action and Therapeutic Potential

4. Ligustilide in Cancer Prevention and Intervention

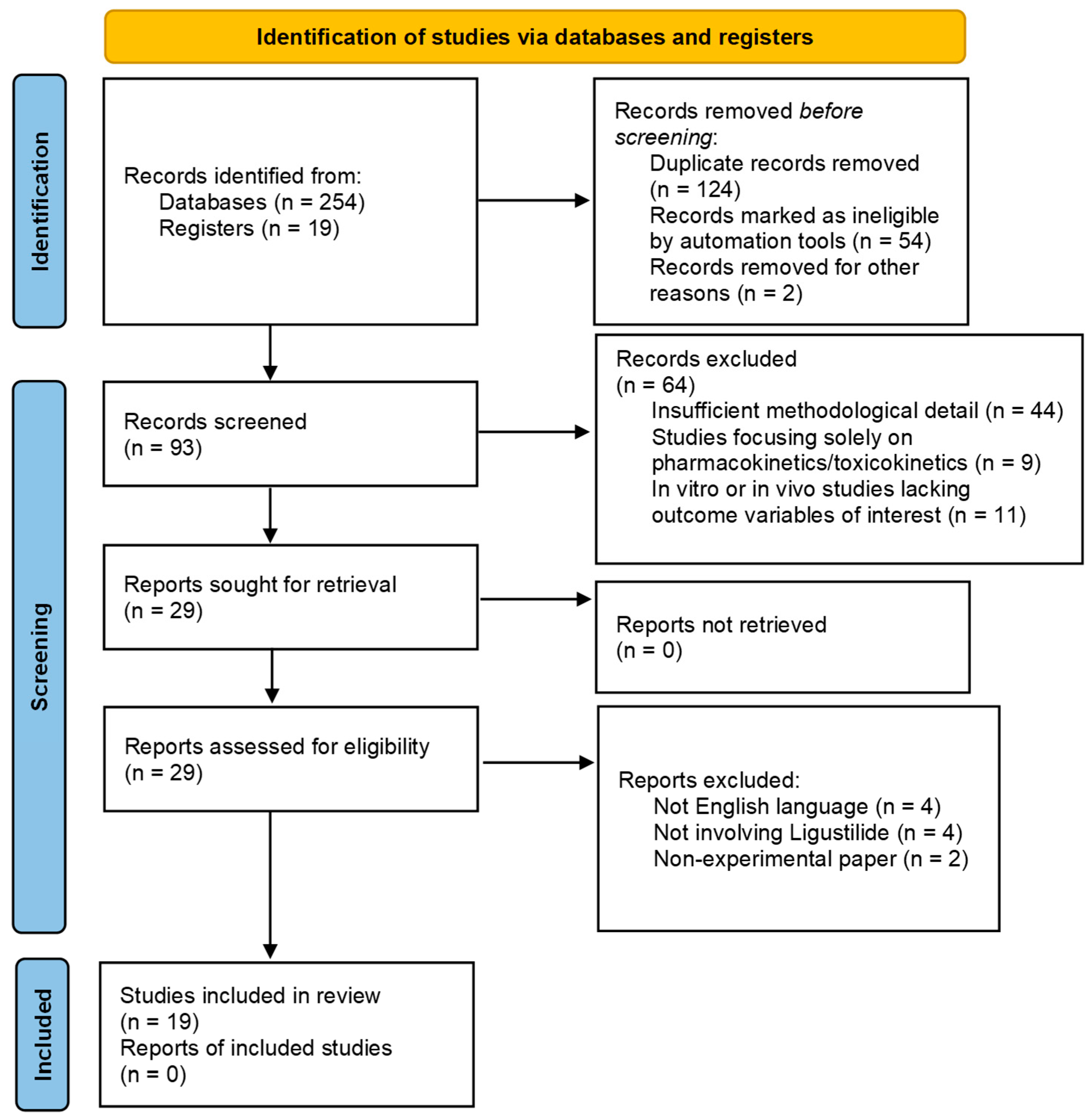

4.1. Literature Search Methodology

4.2. Literature Search Report: Results of Literature Search Following PRISMA Guidelines

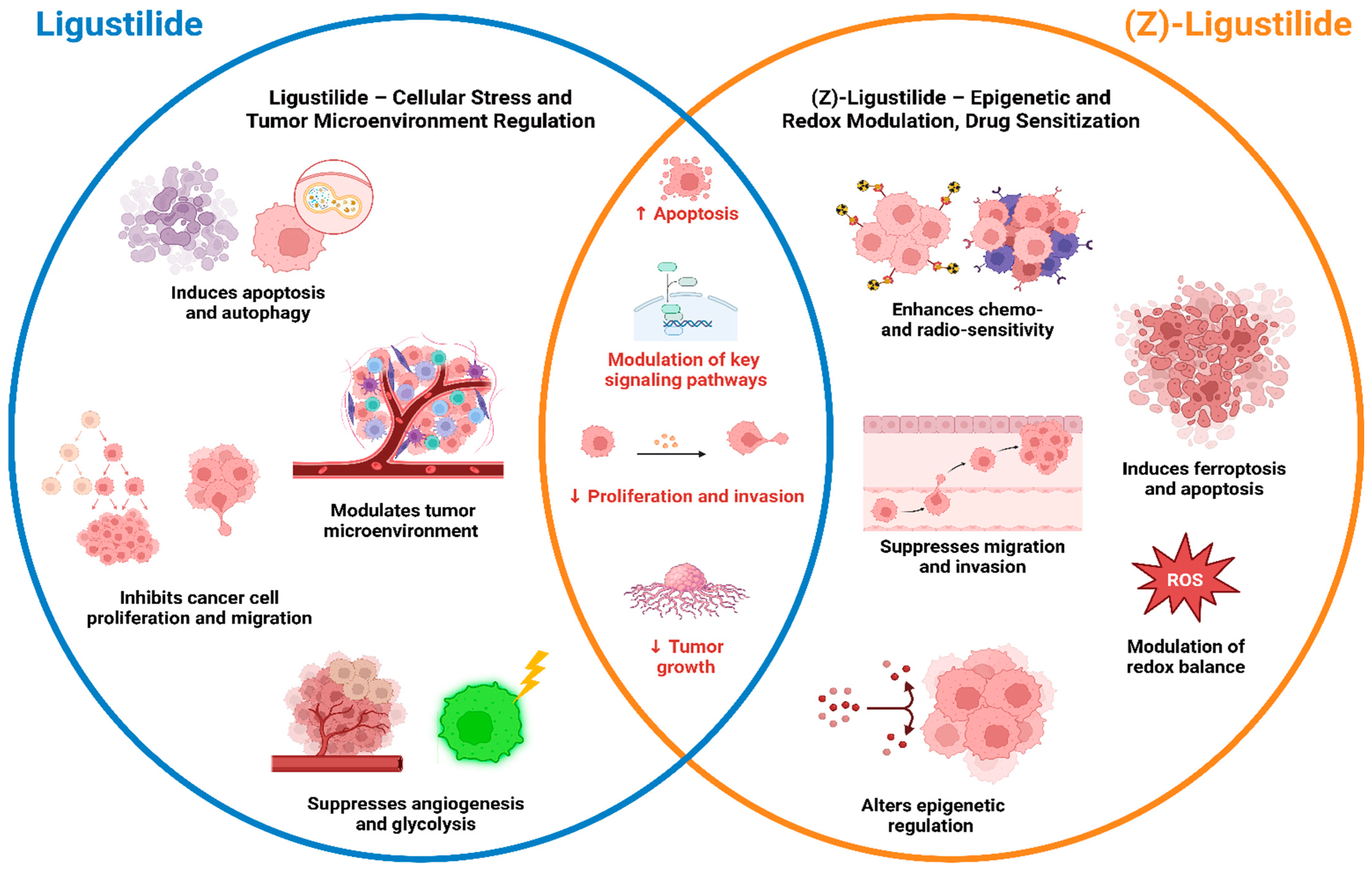

4.3. Preclinical Anticancer Studies of Ligustilide and (Z)-Ligustilide: Mechanisms, Efficacy, and Potential Clinical Implications

4.3.1. Gastric Cancer

4.3.2. Bile Duct Cancer

4.3.3. Breast Cancer

4.3.4. Bladder Cancer

4.3.5. Prostate Cancer

4.3.6. Hepatocellular Carcinoma

4.3.7. Osteoblastoma

4.3.8. Lung Cancer

4.3.9. Acute Myeloid Leukemia

4.3.10. Oral Cancer

4.3.11. Ovarian Cancer

4.3.12. Glioblastoma

5. Advanced Formulation Strategies for Ligustilide

6. Recommendations for Clinical Translation

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ace-H3 | Acetylated histone H3 |

| ACSL4 | Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 |

| ADAM17 | A disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 17 |

| ADME | Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion |

| AKAP1 | A-kinase anchoring protein 1 |

| Akt | Protein Kinase B |

| AML | Acute myeloid leukemia |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| AP-1 | Activator protein-1 |

| AR | Androgen receptor |

| ATG5 | Autophagy-related protein 5 |

| α-SMA | Alpha smooth muscle actin |

| Bax | Bcl-2-associated X protein |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| BNIP-3 | Bcl-2-interacting protein 3 |

| BRCA | Breast cancer gene |

| CAF | Cancer-associated fibroblasts |

| CD | Cluster of Differentiation |

| Cdc42 | Cell division control protein 42 homolog |

| CDKN2A | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A |

| CEBPA | CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha |

| CHOP | C/EBP homologous protein |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| CpG | Cytosine-phosphate-guanine |

| CRPC | Castration-resistant prostate cancer |

| CTSD | Cathepsin D |

| c-Myc | Cellular myelocytomatosis oncogene |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DNMT | DNA methyltransferase |

| EGR1 | Early growth response factor 1 |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| EMT | Epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| ER | Estrogen receptor |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| FGFR3 | Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 |

| FLT3 | Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 |

| FTH1 | Ferritin heavy chain 1 |

| GCL | Glutamate–cysteine ligase |

| GC | Gas chromatography |

| GLUT1 | Glucose transporter 1 |

| GPX4 | Glutathione peroxidase 4 |

| GRP78 | Glucose-regulated protein 78 |

| GSK-3β | Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylase |

| HER2 | Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| HGF | Hepatocyte growth factor |

| HIF | Hypoxia-inducible factor |

| HK | Hexokinase |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase-1 |

| HPV | Human papillomavirus |

| HRAS | Harvey rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog |

| H2AX | H2A histone family member X |

| ICH | International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use |

| IDH | Isocitrate dehydrogenase |

| IFI16 | Interferon-inducible protein 16 |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IL-6R | Interleukin-6 receptor |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| IRP2 | Iron regulatory protein 2 |

| Jab1 | Jun activation domain-binding protein 1 |

| JAK | Janus kinase |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| KRAS | Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog |

| LC3 | Microtubule-associated protein one light chain 3 |

| LDHA | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| LIGc | Ligusticum cycloprolactam |

| lys9/14 | Lysine 9/14 |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| M.SssI | Methyltransferase SssI |

| MTA1 | Metastasis-associated protein 1 |

| MTD | Maximum tolerated dose |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| NDRG1 | N-myc downstream regulated gene 1 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NLRP3 | NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 |

| NOAEL | No observed adverse effect level |

| NPM1 | Nucleophosmin 1 |

| NQO1 | NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 |

| NOR-1 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 3 |

| Nur77 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 1 |

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| PARP | Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase |

| PDK1 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 |

| PERK | Protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase |

| p-PERK | Phosphorylated protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PIK3CA | Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha |

| PIP3 | Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate |

| PKA | Protein kinase A |

| PLPP1 | Phospholipid phosphatase 1 |

| PPAR | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog |

| PTGS2 | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 |

| Rac1 | Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 |

| RB1 | Retinoblastoma-associated protein |

| RFP | Red fluorescent protein |

| Rho | Ras homolog family member |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| Sirt | Sirtuin |

| STAT | Signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| tBID | Truncated BH3-interacting domain death agonist |

| TAM | Tamoxifen |

| Th | T helper lymphocytes |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| TRF1 | Transferrin receptor 1 |

| TrxR | Thioredoxin reductase |

| UGT1A1 | UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 |

| VEGFA | Vascular endothelial growth factor A |

| YAP | Yes-associated protein |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurindo, L.F.; de Lima, E.P.; Laurindo, L.F.; Rodrigues, V.D.; Chagas, E.F.B.; de Alvares Goulart, R.; Araújo, A.C.; Guiguer, E.L.; Pomini, K.T.; Rici, R.E.G.; et al. The therapeutic potential of bee venom-derived Apamin and Melittin conjugates in cancer treatment: A systematic review. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 209, 107430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xiao, X.; Yi, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhu, L.; Shen, Y.; Lin, D.; Wu, C. Tumor initiation and early tumorigenesis: Molecular mechanisms and interventional targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbalho, S.M.; Torres Pomini, K.; Lima, E.P.; da Silva Camarinha Oliveira, J.; Boaro, B.L.; Cressoni Araújo, A.; Landgraf Guiguer, E.; Rici, R.E.G.; Maria, D.A.; Haber, J.; et al. Fantastic Frogs and Where to Use Them: Unveiling the Hidden Cinobufagin’s Promise in Combating Lung Cancer Development and Progression Through a Systematic Review of Preclinical Evidence. Cancers 2024, 16, 3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Visser, K.E.; Joyce, J.A. The evolving tumor microenvironment: From cancer initiation to metastatic outgrowth. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 374–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurindo, L.F.; Sosin, A.F.; Lamas, C.B.; de Alvares Goulart, R.; Dos Santos Haber, J.F.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Barbalho, S.M. Exploring the logic and conducting a comprehensive evaluation of AdipoRon-based adiponectin replacement therapy against hormone-related cancers-a systematic review. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2024, 397, 2067–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.U.; Fatima, K.; Aisha, S.; Malik, F. Unveiling the mechanisms and challenges of cancer drug resistance. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurindo, L.F.; Rodrigues, V.D.; Guiguer, E.L.; Laurindo, L.F.; de Campos Zuccari, D.A.P.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Araújo, A.C.; da Silva Camarinha Oliveira, J.; Maria, D.A.; Dias, J.A.; et al. Catalpol: An Iridoid Glycoside With Potential in Combating Cancer Development and Progression—A Comprehensive Review. Phytother. Res. 2025, 39, 4950–4971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurindo, L.F.; Pomini, K.T.; de Lima, E.P.; Laurindo, L.F.; Rodrigues, V.D.; da Silva Camarinha Oliveira, J.; Araújo, A.C.; Guiguer, E.L.; Rici, R.E.G.; Maria, D.A.; et al. Isoorientin: Unveiling the hidden flavonoid’s promise in combating cancer development and progression—A comprehensive review. Life Sci. 2025, 360, 123280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaro, B.L.; de Lima, E.P.; Maria, D.A.; Rici, R.E.G.; Araújo, A.C.; Guiguer, E.L.; Pereira, E.; Lamas, C.B.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Fiorini, A.M.R.; et al. Cinobufagin: Unveiling the hidden bufadienolide’s promise in combating alimentary canal cancer development and progression—A comprehensive review. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 8075–8089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, L.; Wang, H.; Jiang, M.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, X.; Li, L.; Yin, Q.; Han, L.; Bai, L.; et al. Ligusticum chuanxiong: A chemical, pharmacological and clinical review. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1523176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Mei, W. Advancing brain injury treatment and neuroprotection with ligustilide: Mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Brain Hemorrhages 2025, 6, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, Y.; Qin, G.; Bi, Y.; Yue, G.; Zhang, M.; Chang, X.; Qiu, X.; Luo, L.; Yang, C. Antifungal Effects and Active Components of Ligusticum chuanxiong. Molecules 2022, 27, 4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Rong, L.; Zhang, S.; He, Y.; Song, N.; Zuo, G.; Mei, Z. Ligustilide Inhibits the PI3K/AKT Signalling Pathway and Suppresses Cholangiocarcinoma Cell Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion. Recent Pat. Anti-Cancer Drug Discov. 2025, 20, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xiang, Q.; Mei, S.; Yang, J.; Ma, D.; Wang, B.; Song, E.; Zhu, H. Ligustilide Promotes Gastric Cancer Cell Apoptosis via Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Autophagy. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Qi, X.; Yang, L.R.; Rong, Y.X.; Wei, Q.; Wu, S.Q.; Lu, Q.W.; Li, L.; Jiang, M.D.; et al. Dual role of Nrf2/HO-1 pathway in Z-ligustilide-induced ferroptosis against AML cells. Phytomedicine 2024, 124, 155288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, P.; Zhao, J.; Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Qin, W.; Wang, T.; Shi, X.; Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Qiu, H.; et al. Z-Ligustilide Combined with Cisplatin Reduces PLPP1-Mediated Phospholipid Synthesis to Impair Cisplatin Resistance in Lung Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Huang, M.; Xin, D.; Wang, H.; Yu, H.; Pu, W. Natural products with anti-tumorigenesis potential targeting macrophage. Phytomedicine 2024, 131, 155794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, G.H.; Chan, K.; Chan, C.L.; Leung, K.; Jiang, Z.H.; Zhao, Z.Z. Quantification of ligustilides in the roots of Angelica sinensis and related umbelliferous medicinal plants by high-performance liquid chromatography and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2004, 1046, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhang, L.H.; Lv, G.H.; Wang, X.X.; Jiang, W.D.; Jin, Y.Q.; Zhao, Z.Z. Comparison on content of ligustilides in different danggui samples. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2013, 38, 2838–2843. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Feng, W.M.; Liu, P.; Yan, H.; Yu, G.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, S.; Shang, E.X.; Qian, D.W.; Duan, J.A. Investigation of Enzymes in the Phthalide Biosynthetic Pathway in Angelica sinensis Using Integrative Metabolite Profiles and Transcriptome Analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 928760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, A.; Del-Ángel, M.; Ávila, J.L.; Delgado, G. Phthalides: Distribution in Nature, Chemical Reactivity, Synthesis, and Biological Activity. Prog. Chem. Org. Nat. Prod. 2017, 104, 127–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (PubChem) Compound Summary for CID 5319022, Ligustilide. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Ligustilide (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Mehta, P.; Shah, R.; Lohidasan, S.; Mahadik, K.R. Pharmacokinetic profile of phytoconstituent(s) isolated from medicinal plants—A comprehensive review. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2015, 5, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, R.; Ko, N.L.; Li, S.-L.; Tam, Y.K.; Lin, G. Pharmacokinetics and Metabolism of Ligustilide, a Major Bioactive Component in Rhizoma Chuanxiong, in the Rat. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2008, 36, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, S.; Li, H.; Liu, J. Metabolic profiling of ligustilide and identification of the metabolite in rat and human hepatocytes by liquid chromatography combined with high-resolution mass spectrometry. J. Sep. Sci. 2020, 43, 4405–4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Han, Y.; Tian, Y.; Wu, P.; Xin, A.; Wei, X.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Su, G.; et al. Pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution, and safety evaluation of a ligustilide derivative (LIGc). J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2020, 182, 113140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Pi, M.; Dai, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, W.; Yang, H.; Yao, L. Angelica sinensis and Ligusticum sinense ‘Chuanxiong’ Leaf Essential Oils Promote Hair Growth without Acute Toxicity. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2025, 20, 1934578x251333902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Han, T.; Yu, C.H.; Jiang, Y.P.; Peng, C.; Ran, X.; Qin, L.P. Analysis of the chemical composition, acute toxicity and skin sensitivity of essential oil from rhizomes of Ligusticum chuanxiong. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 144, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhao, P.; Pan, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J. Stabilised pathway and its anti-oxygen/glucose deprived activity about ligustilide, as a pharmacodynamic marker for Angelica sinensis (Oliv) Diles or Ligusticum chuanxiong Hort. Nat. Prod. Res. 2024, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Ming, J.; Li, Y.; Deng, M.; Chen, Q.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S. Ligustilide attenuates nitric oxide-induced apoptosis in rat chondrocytes and cartilage degradation via inhibiting JNK and p38 MAPK pathways. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 3357–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Guo, S.; Wang, W.; Zheng, T.; Jin, X.; Zhou, X.; Gao, W. Preclinical evidence and mechanistic insights of ligustilide in ischemic stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1666207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Qiao, H.; Shi, Y.B. HPLC method with fluorescence detection for the determination of ligustilide in rat plasma and its pharmacokinetics. Pharm. Biol. 2014, 52, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Su, G.; Liu, J.; Song, J.; Chen, W.; Chai, M.; Xie, X.; Wang, M.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z. A Novel Compound Ligusticum Cycloprolactam Alleviates Neuroinflammation After Ischemic Stroke via the FPR1/NLRP3 Signaling Axis. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30, e70158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Bai, L. Anti-inflammatory effects of Z-ligustilide nanoemulsion. Inflammation 2013, 36, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Zhang, M.; Hu, P.; Zhang, J.; Naeem, A.; Wang, L.; Xu, H.; Liu, Y.; Cao, M.; Zheng, Q. Exploratory Study on Nanoparticle Co-Delivery of Temozolomide and Ligustilide for Enhanced Brain Tumor Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Yang, B.; Li, Y.; Sun, X.H.; Li, X.; Sui, P.; Wang, Y.B.; Tian, S.Y.; Wang, C.Y. Ligustilide-loaded liposome ameliorates mitochondrial impairments and improves cognitive function via the PKA/AKAP1 signaling pathway in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30, e14460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, L.; Yu, S. Complexation of Z-ligustilide with hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin to improve stability and oral bioavailability. Acta Pharm. 2014, 64, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liang, J.; Chen, P.; Xu, S.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Lin, C.; Yu, Y.; et al. Ligustilide Suppresses Macrophage-Mediated Intestinal Inflammation and Restores Gut Barrier via EGR1-ADAM17-TNF-α Pathway in Colitis Mice. Research 2025, 8, 0864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Fan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Hua, D.; Ji, Z.; He, W.; Deng, Y.; Geng, D.; Wu, X.; Mao, H. (Z)-Ligustilide alleviates intervertebral disc degeneration by suppressing nucleus pulposus cell pyroptosis via Atg5/NLRP3 axis. Sci. China Life Sci. 2025, 68, 2965–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Chen, T.; Ying, X.; Zhang, Z.; Shao, Z.; Lin, J.; Xu, T.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; et al. Ligustilide alleviated IL-1β induced apoptosis and extracellular matrix degradation of nucleus pulposus cells and attenuates intervertebral disc degeneration in vivo. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 69, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Dong, Z.; Yang, D.; Ma, X.; Wang, X. Alleviation of glucolipotoxicity-incurred cardiomyocyte dysfunction by Z-ligustilide involves in the suppression of oxidative insult, inflammation and fibrosis. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2021, 241, 105138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, T.; Mei, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xue, J.; Luo, Y.; Li, M.; Fang, S.; Pan, H.; et al. Systems pharmacology approach uncovers Ligustilide attenuates experimental colitis in mice by inhibiting PPARγ-mediated inflammation pathways. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2021, 37, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.L.; Zheng, J.Y.; Cai, W.W.; Dai, Z.; Li, B.Y.; Xu, T.T.; Liu, H.F.; Liu, X.Q.; Wei, S.F.; Luo, Y.; et al. Ligustilide improves aging-induced memory deficit by regulating mitochondrial related inflammation in SAMP8 mice. Aging 2020, 12, 3175–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; Deng, Y.F.; Hu, X.Y.; Ni, J.N.; Jiang, M.; Bai, G. Phthalides, senkyunolide A and ligustilide, show immunomodulatory effect in improving atherosclerosis, through inhibiting AP-1 and NF-κB expression. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 117, 109074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, E.S.; Yoon, J.J.; Han, B.H.; Jeong, D.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Kang, D.G.; Lee, H.S. Ligustilide attenuates vascular inflammation and activates Nrf2/HO-1 induction and, NO synthesis in HUVECs. Phytomedicine 2018, 38, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Uchi, H.; Morino-Koga, S.; Shi, W.; Furue, M. Z-ligustilide ameliorated ultraviolet B-induced oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokine production in human keratinocytes through upregulation of Nrf2/HO-1 and suppression of NF-κB pathway. Exp. Dermatol. 2015, 24, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Cai, C.; Huang, W.; Zhong, C.; Zhao, T.; Di, J.; Tang, J.; Wu, D.; Pang, M.; He, L.; et al. Enhancing mitophagy by ligustilide through BNIP3-LC3 interaction attenuates oxidative stress-induced neuronal apoptosis in spinal cord injury. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 20, 4382–4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Chen, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhang, J. Z-ligustilide provides a neuroprotective effect by regulating the phenotypic polarization of microglia via activating Nrf2-TrxR axis in the Parkinson’s disease mouse model. Redox Biol. 2024, 76, 103324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, K.; Jin, Z.; Qiu, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, Y.; Qiu, T.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Z. Ligustilide alleviates oxidative stress during renal ischemia-reperfusion injury through maintaining Sirt3-dependent mitochondrial homeostasis. Phytomedicine 2024, 134, 155975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Gong, J.; Cao, X.; Liu, S. Ligustilide modulates oxidative stress, apoptosis, and immunity to avoid pathological damages in bleomycin induced pulmonary fibrosis rats via inactivating TLR4/MyD88/NF-KB P65. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, X.; Xie, Y.; Qu, Y.; Long, H.; Gu, N.; Jiang, W. Z-Ligustilide protects vascular endothelial cells from oxidative stress and rescues high fat diet-induced atherosclerosis by activating multiple NRF2 downstream genes. Atherosclerosis 2019, 284, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, A.F.; Khodier, A.E.; Al-Gayyar, M.M. Antitumor Activity of Ligustilide Against Ehrlich Solid Carcinoma in Rats via Inhibition of Proliferation and Activation of Autophagy. Cureus 2023, 15, e40499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Ying, L.; Guo, R.; Hao, M.; Liang, Y.; Bi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yu, C.; Yang, Z. Ligustilide induces apoptosis and reduces proliferation in human bladder cancer cells by NFκB1 and mitochondria pathway. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2023, 101, 1252–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Tao, N.; Qin, Z. Ligustilide Inhibits Tumor Angiogenesis by Downregulating VEGFA Secretion from Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in Prostate Cancer via TLR4. Cancers 2022, 14, 2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Mei, J.; Lu, J.; Wang, Y.; Hu, M.; Ma, F.; Long, H.; Qin, Z.; Tao, N. Ligustilide promotes apoptosis of cancer-associated fibroblasts via the TLR4 pathways. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 135, 110991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Xu, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Wang, Y.; Hu, M.; Ma, F.; Long, H.; Qin, Z.; Tao, N. Ligustilide inhibits the activation of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Life Sci. 2019, 218, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xing, Z. Ligustilide counteracts carcinogenesis and hepatocellular carcinoma cell-evoked macrophage M2 polarization by regulating yes-associated protein-mediated interleukin-6 secretion. Exp. Biol. Med. 2021, 246, 1928–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, L.; Cha, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Xie, B.; Li, B.; Zheng, L. Ligustilide inhibits the proliferation of human osteoblastoma MG63 cells through the TLR4-ERK pathway. Life Sci. 2022, 288, 118993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, G.; Dou, G.; Yang, Y.; Chen, L.; Ma, H.; Jiang, Z.; Ma, H.; Li, C.; Li, L.; et al. Z-Ligustilide Selectively Targets AML by Restoring Nuclear Receptors Nur77 and NOR-1-mediated Apoptosis and Differentiation. Phytomedicine 2021, 82, 153448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhao, W.; Zhu, F.; Wu, H.; Ding, X.; Bai, J.; Zhang, X.; Qian, M. Ligustilide inhibits the proliferation of non-small cell lung cancer via glycolytic metabolism. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2021, 410, 115336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, R.J.; Peng, K.Y.; Hsu, W.L.; Chen, Y.T.; Liu, D.W. Z-Ligustilide Induces c-Myc-Dependent Apoptosis via Activation of ER-Stress Signaling in Hypoxic Oral Cancer Cells. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 824043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, F.; Qu, J.; Yin, H.; Li, L.; Zhi, Y.; Liu, Y.; Fang, Z.; Hao, E. Apoptotic cell death induced by Z-Ligustilidein human ovarian cancer cells and role of NRF2. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 121, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, C.; Yang, Y.; Li, L.; He, H.; Yu, Z. Sensitization of tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells by Z-ligustilide through inhibiting autophagy and accumulating DNA damages. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 29300–29317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Li, L.; Dou, G.; Wang, C.; Li, J.; He, H.; Wu, M.; Qi, H. Z-ligustilide restores tamoxifen sensitivity of ERa negative breast cancer cells by reversing MTA1/IFI16/HDACs complex mediated epigenetic repression of ERa. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 29328–29345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.; Wang, C.; Mody, A.; Bao, L.; Hung, S.H.; Svoronos, S.A.; Tseng, Y. The Effect of Z-Ligustilide on the Mobility of Human Glioblastoma T98G Cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.Y.; Khor, T.O.; Shu, L.; Lee, J.H.; Saw, C.L.; Wu, T.Y.; Huang, Y.; Suh, N.; Yang, C.S.; Conney, A.H.; et al. Epigenetic reactivation of Nrf2 in murine prostate cancer TRAMP C1 cells by natural phytochemicals Z-ligustilide and Radix angelica sinensis via promoter CpG demethylation. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2013, 26, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freile, B.; van Schooten, T.S.; Derks, S.; Carneiro, F.; Figueiredo, C.; Barros, R.; Gauna, C.; Pereira, R.; Romero, M.; Riquelme, A.; et al. Gastric cancer hospital-based registry: Real-world gastric cancer data from Latin America and Europe. ESMO Gastrointest. Oncol. 2024, 6, 100088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yang, W.J.; Hu, B. Gastric epithelial histology and precancerous conditions. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2022, 14, 396–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Xu, Y.; Dou, Y.; Xu, D. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: Mechanisms and new perspectives. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Wu, K.; Gu, M.; Yang, Y.; Tu, J.; Huang, X. Reversal of chemotherapy resistance in gastric cancer with traditional Chinese medicine as sensitizer: Potential mechanism of action. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1524182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.S.; Liu, Y.Y.; Zhang, S.K.; Zhou, J.Y.; Li, J.H.; Li, X.M.; Zhang, M.H.; Pan, X.Y.; Chai, Y.B.; Fang, W.X.; et al. Lipidomic profiling of human bile distinguishes cholangiocarcinoma from benign bile duct diseases with high specificity and sensitivity: A prospective descriptive study. Br. J. Cancer 2025, 133, 1565–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brindley, P.J.; Bachini, M.; Ilyas, S.I.; Khan, S.A.; Loukas, A.; Sirica, A.E.; Teh, B.T.; Wongkham, S.; Gores, G.J. Cholangiocarcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qurashi, M.; Vithayathil, M.; Khan, S.A. Epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2025, 51, 107064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Xu, S.; Deng, Z.; Wang, M.J.; Chen, F. Molecular mechanisms and genetic features of cholangiocarcinoma: Implications for targeted therapeutic strategies. Precis. Clin. Med. 2025, 8, pbaf021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Dai, F.; Ye, Y.; Qian, J. The global burden of breast cancer among women of reproductive age: A comprehensive analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurson, A.N.; Ahearn, T.U.; Koka, H.; Jenkins, B.D.; Harris, A.R.; Roberts, S.; Fan, S.; Franklin, J.; Butera, G.; Keeman, R.; et al. Risk factors for breast cancer subtypes by race and ethnicity: A scoping review. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2024, 116, 1992–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Rozen, V.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z. Oncogenic activation of PI K3 CA in cancers: Emerging targeted therapies in precision oncology. Genes. Dis. 2025, 12, 101430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvalim, C.; Datta, A.; Lee, S.C. Role of p53 in breast cancer progression: An insight into p53 targeted therapy. Theranostics 2023, 13, 1421–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, X.; Zheng, L.W.; Ding, Y.; Chen, Y.F.; Cai, Y.W.; Wang, L.P.; Huang, L.; Liu, C.C.; Shao, Z.M.; Yu, K.D. Breast cancer: Pathogenesis and treatments. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolarz, B.; Nowak, A.Z.; Romanowicz, H. Breast Cancer-Epidemiology, Classification, Pathogenesis and Treatment (Review of Literature). Cancers 2022, 14, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.D.; Quinn, A.E.; Bajo, A.; Mayberry, T.G.; Cowan, B.C.; Marrah, A.J.; Wakefield, M.R.; Fang, Y. Squamous Cell Bladder Cancer: A Rare Histological Variant with a Demand for Modern Cancer Therapeutics. Cancers 2025, 17, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jia, H.; Han, H. Emerging drivers of female bladder cancer: A pathway to precision prevention and treatment. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1497637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.; Sonpavde, G. Molecularly Targeted Therapy towards Genetic Alterations in Advanced Bladder Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fan, X.; Chen, Y.; Han, Y.; Yu, W.; Zhang, S.; Yang, B.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y. An unfolded protein response (UPR)-signature regulated by the NFKB-miR-29b/c axis fosters tumor aggressiveness and poor survival in bladder cancer. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2025, 12, 1542650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.S.; Baek, S.W.; Yang, G.E.; Mun, J.Y.; Kim, J.A.; Kim, T.N.; Nam, J.K.; Choi, Y.H.; Lee, J.S.; Chu, I.S.; et al. Chemoresistance-motility signature of molecular evolution to chemotherapy in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer and its clinical implications. Cancer Lett. 2025, 610, 217339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawla, P. Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer. World J. Oncol. 2019, 10, 63–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maekawa, S.; Takata, R.; Obara, W. Molecular Mechanisms of Prostate Cancer Development in the Precision Medicine Era: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Zieren, R.C.; Xue, W.; de Reijke, T.M.; Pienta, K.J. Metastatic prostate cancer remains incurable, why? Asian J. Urol. 2019, 6, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, B.; Lu, Y.; Li, X.; Wei, Y.; Ye, D.; Wei, G.; Zhu, Y. Targeting the tumor microenvironment, a new therapeutic approach for prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2025, 28, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llovet, J.M.; Kelley, R.K.; Villanueva, A.; Singal, A.G.; Pikarsky, E.; Roayaie, S.; Lencioni, R.; Koike, K.; Zucman-Rossi, J.; Finn, R.S. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wang, S.; Xia, L.; Sun, Z.; Chan, K.M.; Bernards, R.; Qin, W.; Chen, J.; Xia, Q.; Jin, H. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Signaling pathways and therapeutic advances. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Hao, L.; Li, N.; Hu, X.; Yan, H.; Dai, E.; Shi, X. Targeting the Hippo/YAP1 signaling pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma: From mechanisms to therapeutic drugs (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2024, 65, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Cui, T.; Wei, F.; Zhou, Z.; Sun, Y.; Gao, C.; Xu, X.; Zhang, H. Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma: Pathogenic role and therapeutic target. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1367364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Lin, H.; Wu, G.; Zhu, M.; Li, M. IL-6/STAT3 Is a Promising Therapeutic Target for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 760971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, S.; Krishna, V.K.; Periasamy, S.; Kumar, S.P.; Krishnan, M. A Rare Case of Benign Osteoblastoma of the Mandible. Cureus 2022, 14, e25799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shen, H.; Guan, Y. Aggressive osteoblastoma of the frontal bone invading the dura: A case report and a review of related literature. Medicine 2025, 104, e44076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alduais, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fan, F.; Chen, J.; Chen, B. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): A review of risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Medicine 2023, 102, e32899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Ge, T.; Jiang, M.; Jia, K.; Wang, L.; Li, W.; Chen, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, S.; et al. Early diagnosis of lung cancer: Which is the optimal choice? Aging 2021, 13, 6214–6227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaed, B.; Bobik, N.; Laitinen, H.; Nandikonda, T.; Ilonen, I.; Haikala, H.M. Shaping the battlefield: EGFR and KRAS tumor mutations’ role on the immune microenvironment and immunotherapy responses in lung cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2025, 44, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Jia, L.; Tang, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, G.; Wang, S. Regulation of cisplatin resistance in lung cancer by epigenetic mechanisms. Clin. Epigenetics 2025, 17, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javier-Rojas, W.J.; Newman-Caro, A.B.; Lin, Y.; Montero, C. Simultaneous Onset of Acute Myeloid Leukemia and Decompensated Cirrhosis: A Rare Case. Cureus 2025, 17, e86990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurzer, J.H.; Weinberg, O.K. Updates in molecular genetics of acute myeloid leukemia. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2023, 40, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ningombam, A.; Verma, D.; Kumar, R.; Singh, J.; Ali, M.S.; Pandey, A.K.; Singh, I.; Bakhshi, S.; Sharma, A.; Pushpam, D.; et al. Prognostic relevance of NPM1, CEBPA, and FLT3 mutations in cytogenetically normal adult AML patients. Am. J. Blood Res. 2023, 13, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wan, D.; Jiang, Z. Clinical implications of recurrent gene mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouligny, I.M.; Maher, K.R.; Grant, S. Mechanisms of myeloid leukemogenesis: Current perspectives and therapeutic objectives. Blood Rev. 2023, 57, 100996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimony, S.; Stahl, M.; Stone, R.M. Acute myeloid leukemia: 2023 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am. J. Hematol. 2023, 98, 502–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, P.; Aryal, S.; Franceski, A.M.; Kuznetsova, V.; Costa, A.; Luca, F.; Connelly, A.N.; Phillips, D.W.; Ennis, C.C.; Curtiss, B.M.; et al. The acute myeloid leukemia microenvironment impairs neutrophil maturation and function through NF-κB signaling. Blood 2025, 146, 1707–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eloranta, R.; Vilén, S.T.; Keinänen, A.; Salo, T.; Qannam, A.; Bello, I.O.; Snäll, J. Oral squamous cell carcinoma: Effect of tobacco and alcohol on cancer location. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2024, 22, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchibori, M.; Osawa, Y.; Ishii, Y.; Aoki, T.; Ota, Y.; Kimura, M. Analysis of HRAS mutations in Japanese patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Adv. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 1, 100021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, M.; Li, B.; Huang, Z.; Qin, S.; Nice, E.C.; Tang, J.; Huang, C. Oral squamous cell carcinomas: State of the field and emerging directions. Int. J. Oral. Sci. 2023, 15, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muralidharan, S.; Nikalje, M.; Subramaniam, T.; Koshy, J.A.; Koshy, A.V.; Bangera, D. A Narrative Review on Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2025, 17, S204–S206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotnik, E.N.; Mullen, M.M.; Spies, N.C.; Li, T.; Inkman, M.; Zhang, J.; Martins-Rodrigues, F.; Hagemann, I.S.; McCourt, C.K.; Thaker, P.H.; et al. Genetic characterization of primary and metastatic high-grade serous ovarian cancer tumors reveals distinct features associated with survival. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinne, N.; Christie, E.L.; Ardasheva, A.; Kwok, C.H.; Demchenko, N.; Low, C.; Tralau-Stewart, C.; Fotopoulou, C.; Cunnea, P. Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in epithelial ovarian cancer, therapeutic treatment options for platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2021, 4, 573–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arczewska, K.D.; Piekiełko-Witkowska, A. DNA Damage and Repair in Ovarian Cancer: Focus on MicroRNAs. Cancers 2025, 17, 3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.K.; Ding, D.C. Early Diagnosis of Ovarian Cancer: A Comprehensive Review of the Advances, Challenges, and Future Directions. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Qiu, W.; Sun, T.; Wang, L.; Du, C.; Hu, Y.; Liu, W.; Feng, F.; Chen, Y.; Sun, H. Therapeutic strategies of glioblastoma (GBM): The current advances in the molecular targets and bioactive small molecule compounds. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 1781–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Li, F.; Wang, J.; Zou, Y.; Tang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Jiang, X. HIF-1α Mediated Regulation of Glioblastoma Malignant Phenotypes through CD47 Protein: Understanding Functions and Mechanisms. J. Cancer 2025, 16, 750–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salbini, M.; Formato, A.; Mongiardi, M.P.; Levi, A.; Falchetti, M.L. Kinase-Targeted Therapies for Glioblastoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Tang, T. MAPK signaling pathway-based glioma subtypes, machine-learning risk model, and key hub proteins identification. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, W.; Meng, F.; Yi, T. A Spray-Dried Self-Stabilizing Nanocrystal Emulsion of Traditional Chinese Medicine: Preparation, Characterization and ex vivo Intestinal Absorption. Pharm. Front. 2024, 06, e449–e458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cell Line (s)/Animal Model (s) | IC50/EC50/Concentration and Duration | Effects Demonstrated | Mechanisms of Action | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastric cancer | ||||

| In vitro: MKN74, AGS. In vivo: tumor xenograft (MKN74 cells)-bearing nude mice. | In vitro: 5, 10, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 200 and 300 µM, 24 and 48 h. In vivo: 5 mg/kg (intraperitoneal injection) for 20 days. | In vitro: ↑ apoptosis and cell cycle arrest, ┴ cell growth. In vivo: ↓ tumor volume and weight. | In vitro: ↑ caspase-3 activity and PARP cleavage, ↑ Bax, ↓ mitochondrial Bcl-2, ↑ autophagy (↑ LC3-II/LC3-I ratio, ↓ p62 protein levels, ↑ ATG5 expression), upregulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress markers (GRP78, CHOP), phosphorylation of PERK. In vivo: ↑ cleaved caspase-3 and p-PERK signals, ↑ autophagy (LC3). | Liu et al. (2025) [15] |

| Bile duct cancer | ||||

| In vitro: HuccT1 and RBE. In vivo: NOG mice with cholangiocarcinoma. | In vitro: 5.08 µg/mL, 48 h (IC50—HuccT1 cells); 5.77 µg/mL, 48 h (IC50—RBE cells). In vivo: 5 mg/kg (intraperitoneal injection) for 18 days. | In vitro: ┴ cell proliferation, migration and invasion. In vivo: ↓ tumor volume. | In vitro: ↑ E-cadherin expression, ↓ N-cadherin expression, ↑ NDRG1, ┴ PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. In vivo: downregulation of Ki67 expression. | Wu et al. (2025) [14] |

| Mammary tumor | ||||

| In vivo: Sprague-Dawley rats with Ehrlich solid carcinoma. | In vivo: 20 mg/kg (oral gavage) for 3 weeks. | In vivo: ↓ tumor weight and volume, ┴ cell proliferation, ┴ apoptosis. | In vivo: ┴ Ki67 and mTOR, ↓ AMPK expression, ↑ Bcl-2, ↑ autophagy (beclin 1 activation). | Alshehri et al. (2023) [54] |

| Bladder cancer | ||||

| In vitro: T24 and EJ-1. In vivo: xenograft tumor (T24 and EJ-1 cells)-bearing nude mice. | In vitro: 209.8 µM, 24 h (IC50—T24 cells); 215.2 µM, 48 h (IC50—T24 cells); 240.4 µM, 24 h (IC50—EJ-1 cells); 230.3 µM, 48 h (IC50—EJ-1 cells). In vivo: 10 mg/kg (intraperitoneal injection) every 3 days for 27 or 30 days. | In vitro: ┴ cell proliferation and the cell cycle at the sub-G1 phase, ↑ apoptosis. In vivo: ↓ tumor volume and weight. | In vitro: upregulation of the expression of caspase-8, tBID and Bax proteins, downregulation of the expression of NF-κB1 (p50) protein. In vivo: promotes cancer cell death through mitochondrial regulation and NF-κB1-mediated pathways. | Yin et al. (2023) [55] |

| Prostate cancer | ||||

| In vitro: prostate CAF. In vivo: subcutaneous tumor (RM-1 cells)-bearing C57BL/6 mice. | In vitro: 10, 20 and 40 µM, 1, 2, 4, 6, 12, 24 and 48 h. In vivo: 5 mg/kg (intraperitoneal injection) daily for 18 days. | In vitro: ┴ pro-angiogenesis effect of CAF, ┴ glycolysis in CAF. In vivo: ↓ vascular density in cancer tissue. | In vitro: phosphorylation of p38, ERK and JNK, activation of the TLR4-AP-1 signaling pathway, ↓ expression levels of α-SMA and VEGFA, ┴ HIF-1, ↓ HK1/2, GLUT1, PDK1, LDHA, upregulation of p53 and Jab1. In vivo: ↓ expression levels of α-SMA, CD31, VEGFA and HGF. | Ma et al. (2022) [56] |

| In vitro: prostate CAF and PC-3. In vivo: tumor (RM-1 cells)-bearing C57BL/6 mice and TLR4−/− mice. | In vitro: 0.146 mM (IC50, CAF); 0.01, 0.02, 0.04, 0.08, 0.16, 0.24 and 0.32 mM, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, and 24 h. In vivo: 5 mg/kg (intraperitoneal injection). | In vitro: ┴ cell proliferation, ↑ apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. In vivo: ┴ tumor growth. | In vitro: modulation of p21, cyclin B1 and cyclin D1, ↑ phosphorylation of p53, ↑ Bax, cytochrome C and cleaved caspase-3/-9, downregulation of Bcl-2, modulation of TLR4. In vivo: modulation of TLR4. | Ma et al. (2020) [57] |

| In vitro: prostate CAF. | In vitro: 15, 20, 30 and 45 µM, 24 h and 4 days. | In vitro: reversion of the immunosuppressive function of CAF and restoration of T-cell proliferation. | In vitro: activation of the NF-κB pathway, modulation of TLR4, ↓ α-SMA. | Ma et al. (2019) [58] |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | ||||

| In vitro: HepG2. | In vitro: 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100 and 200 µM, 24 h. | In vitro: ┴ cell viability and migration, ↓ cancer cell malignancy. | In vitro: ┴ YAP activation, ↓ IL-6 release, ┴ IL-6R/STAT3 signaling activation, ┴ cancer cells’ ability to recruit and skew macrophages toward M2 phenotype. | Yang & Xing (2021) [59] |

| Osteoblastoma | ||||

| In vitro: MG63. | In vitro: 0.294 mM (IC50). | In vitro: ┴ cell proliferation, ↑ apoptosis, arrested the cell cycle in G2-M phase. | In vitro: modulation of TLR4, upregulation of p-p53, p21, cyclin D1, p-Tak1, p-ERK and Bax, downregulation of p53, cyclin B1, Tak1 and ERK, activation of Caspase family. | Zhang et al. (2022) [60] |

| Cell Line (s)/Animal Model (s) | IC50/EC50/Concentration and Duration | Effects Demonstrated | Mechanisms of Action | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute myeloid leukemia | ||||

| In vitro: HL-60, MV-4-11 and primary AML cells. In vivo: HL-60 cells injected in BALB/c-nu nude mice. | In vitro: 28.58 ± 2.53 µM (IC50—HL-60 cells); 25.37 ± 2.70 µM (IC50—MV-4-11 cells); 6.25, 12.5, 25, 30, 50, 70 and 100 µM, 6, 24, 48 and 72 h. In vivo: 40 mg/kg/2 days (intraperitoneal injection) for 12 days. | In vitro: ┴ cell viability, promotion of iron metabolism disorder, ↑ cell death and ferroptosis. In vivo: ↓ tumor growth, ↓ white blood cell counts in the peripheral blood of mice, improved inflammatory cell infiltration into the liver and hepatic sinusoidal contraction. | In vitro: modulation of Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, ↑ ROS and lipid peroxidation, ↓ IRP2 protein and TRF1 expression, ↑FTH1 expression, ↑ ACSL4 and PTGS2 protein levels, ↓ GPX4 levels. In vivo: ↑ Nrf2 and HO-1 proteins. | Chen et al. (2024) [16] |

| In vitro: HL-60, Kasumi-1 and MV-4-11. In vivo: HL-60 cells injected in NOD/SCID mice. | In vitro: 23.5 µM, 72 h (IC50—HL-60 cells); 36.1 µM, 72 h (IC50—Kasumi-1 cells); 11.9 µM, 72 h (IC50—MV-4-11 cells). In vivo: 80 mg/kg (intraperitoneal injection) once every other day for 2 weeks. | In vitro: ┴ cell viability, ↑ apoptosis (at higher concentrations of Z-Ligustilide) and cell differentiation (at lower concentrations of Z-Ligustilide). In vivo: ↑ mice survival rate, ↓ splenomegaly, ↓ white blood cell and lymphocyte counts in mice. | In vitro: restoration of Nur77 and NOR-1 expression through histone acetylation, ↑ recruitment of p300, ↓ recruitment of HDAC1, HDAC4/5/7 and MTA1 in the Nur77 promoter region, ↓ HDAC1 and HDAC3 in the NOR-1 promoter region. In vivo: restoration of Nur77 and NOR-1. | Wang et al. (2021) [61] |

| Lung cancer | ||||

| In vitro: A549, A549/DDP (cisplatin-resistant), H460 and H460/DDP (cisplatin-resistant). | In vitro: 15, 30, 60, 120, 180 and 240 µM, 24 h. | In vitro: ┴ cell viability, ↓ cisplatin resistance of A549/DDP and H460/DDP. | In vitro: (Z)-Ligustilide plus cisplatin induced ↑ PLPP1 expression and ┴ PIP3/Akt axis. | Geng et al. (2023) [17] |

| In vitro: H1299 and A549. In vivo: BALB/c nude mice with orthotopic tumor (A549 cells). | In vitro: 15, 30, 60, 120 and 180 µM, 12, 24 and 48 h. In vivo: 5 mg/kg (intraperitoneal injection). | In vitro: ┴ cell proliferation, ↑ apoptosis, ↓ aerobic glycolysis of the cells. In vivo: ↓ tumor size, volume and weight. | In vitro: upregulation of PTEN, ┴ phosphorylation of Akt, ↑ caspase-3/-7 activity, downregulation of GLUT1, HK1/2, LDHA and PDK1. In vivo: ↓ percentage of Ki-67-positive cells in tumor tissues, modulation of PTEN/Akt signaling pathway. | Jiang et al. (2021) [62] |

| Oral cancer | ||||

| In vitro: TW2.6, OML1 and SCC-25. | In vitro: 25, 50, 100 and 200 µM, 6, 16 and 24 h. | In vitro: ↑ apoptosis, ┴ cell migration, ↑ cancer’s radiosensitivity. | In vitro: activation of endoplasmic reticulum-stress signaling, modulation of HIF-1α, ↑ c-Myc protein levels and cleaved caspase-3, ↑ γ-H2AX expression. | Hsu et al. (2022) [63] |

| Ovarian cancer | ||||

| In vitro: OVCAR-3. | In vitro: 50, 100 and 200 µM. | In vitro: ↑ apoptosis and total cell death, ↑ oxidative stress. | In vitro: ↑ mitochondrial superoxide formation, ↓ mitochondrial polarization, ↑ ROS, ↑ nuclear level of Nrf2 and its downstream target genes (HO-1, NQO-1, UGT1A1, GCL). | Lang et al. (2018) [64] |

| Breast cancer | ||||

| In vitro: MCF-7, MCF-7TR5 (TAM-resistant), T47D and T47DTR5 (TAM-resistant). | In vitro: 25, 50, 100 and 200 µM, 3, 6, 12, 24 and 48 h. | In vitro: sensitizes TAM-resistant cells to apoptosis, ┴ autophagy and autophagosome-lysosome fusion in MCF-7TR5. | In vitro: restoration of the interaction between Nur77 and Ku80, ↑ LC3-II/LC3-I ratio and accumulation of RFP-LC3 puncta, ↑ p62 protein level, downregulation of CTSD. | Qi et al. (2017) [65] |

| In vitro: MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-453 and HS578t. | In vitro: 10, 25, 50 µM, 12, 24, 36, 48 and 72 h. 133.6 µM (IC50—MDA-MB-231 cells). | In vitro: reactivation of ERα protein expression and restoration of cells’ sensitivity to TAM. | In vitro: ↑ Ace-H3 (lys9/14) level in the ERα promoter region, ↓ MTA1, IFI16 and HDAC expression. | Ma et al. (2017) [66] |

| Glioblastoma | ||||

| In vitro: T98G. | In vitro: 2.5, 5, 10 and 25 µM, 14 and 20 h. | In vitro: ↓ cell mobility, single cell migration and wound-like gap closure capacity. | In vitro: ↓ expression levels of the Rho GTPases (RhoA, Rac1, Cdc42). | Yin et al. (2013) [67] |

| Prostate cancer | ||||

| In vitro: TRAMP C1. | In vitro: 6.25, 12.5, 20, 25, 40, 50, 60, 80 and 100 µM, 1, 3 and 5 days. IC50: 1055 µM (specific for inhibition of M.SssI activity). | In vitro: ↓ cell viability. | In vitro: ↑ Nrf2 and Nrf2-mediated enzymes (HO-1, NQO1, UGT1A1), ┴ DNMT activity of M.SssI, ↓ methylated CpG ratio in the Nrf2 gene promoter region. | Su et al. (2013) [68] |

| Cancer Type | Model Type | Model Used | Dose/Exposure | Primary Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastric cancer | In vitro/In vivo | MKN74, AGS; xenograft mice | 5–300 µM; 5 mg/kg i.p. | Apoptosis induction; ↓ tumor volume | Liu et al. (2025) [15] |

| Bile duct cancer | In vitro/In vivo | HuccT1, RBE; NOG mice | ~5 µg/mL; 5 mg/kg i.p. | ┴ proliferation and migration; ↓ tumor volume | Wu et al. (2025) [14] |

| Mammary tumor | In vivo | Sprague-Dawley rats | 20 mg/kg oral | ↓ tumor weight/volume | Alshehri et al. (2023) [54] |

| Bladder cancer | In vitro/In vivo | T24, EJ-1; xenograft mice | ~209–240 µM; 10 mg/kg i.p. | ↑ apoptosis; ↓ tumor size | Yin et al. (2023) [55] |

| Prostate cancer | In vitro/In vivo | CAF, PC-3; C57BL/6 and TLR4−/− mice | 10–45 µM and 0.01–0.32 mM; 5 mg/kg i.p. | Anti-angiogenic; ↓ tumor growth; immunomodulation | Ma et al. (2022; 2020; 2019) [56,57,58] |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | In vitro | HepG2 | 2.5–200 µM | ┴ viability and migration | Yang & Xing (2021) [59] |

| Osteoblastoma | In vitro | MG63 | ~0.3 mM | ↑ apoptosis | Zhang et al. (2022) [60] |

| Lung cancer | In vitro/In vivo | A549, H1299; nude mice with orthotopic tumor | 15–180 µM; 5 mg/kg i.p. | ┴ proliferation; ↓ tumor growth | Jiang et al. (2021) [62] |

| AML | In vitro/In vivo | HL-60, MV-4-11, primary AML cells, Kasumi-1; BALB/c mice, NOD/SCID mice | 6.25–100 µM; 40–80 mg/kg | Ferroptosis induction; ↓ leukemic burden | Chen et al. (2024); Wang et al. (2021) [16,61] |

| Lung cancer (cisplatin-resistant) | In vitro | A549/DDP, H460/DDP | 15–240 µM | ↓ cisplatin resistance | Geng et al. (2023) [17] |

| Oral cancer | In vitro | TW2.6, OML1, SCC-25 | 25–200 µM | ↑ apoptosis; ↑ radiosensitivity | Hsu et al. (2022) [63] |

| Ovarian cancer | In vitro | OVCAR-3 | 50–200 µM | ↑ apoptosis; ↑ oxidative stress | Lang et al. (2018) [64] |

| Breast cancer | In vitro | MCF-7, T47D, and TAM-resistant lines; MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-453, and HS578t | 10–200 µM | Restores TAM sensitivity; ↑ ERα expression | Qi et al. (2017); Ma et al. (2017) [65,66] |

| Glioblastoma | In vitro | T98G | 2.5–25 µM | ↓ migration | Yin et al. (2013) [67] |

| Prostate cancer | In vitro | TRAMP C1 | 6.25–100 µM | ↑ Nrf2 signaling; ┴ DNMT activity | Su et al. (2013) [68] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dogani Rodrigues, V.; Longui Cabrini, M.; de Souza Bastos Mazuqueli Pereira, E.; dos Santos Bueno, M.; Catharin, V.M.; dos Santos Haber, J.F.; Gomes Eleutério, R.; Indiani, L.; Cavallari Strozze Catharin, V.; Cristina Ferraroni Sanches, R.; et al. Ligustilide: A Phytochemical with Potential in Combating Cancer Development and Progression—A Comprehensive and Critical Review. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010036

Dogani Rodrigues V, Longui Cabrini M, de Souza Bastos Mazuqueli Pereira E, dos Santos Bueno M, Catharin VM, dos Santos Haber JF, Gomes Eleutério R, Indiani L, Cavallari Strozze Catharin V, Cristina Ferraroni Sanches R, et al. Ligustilide: A Phytochemical with Potential in Combating Cancer Development and Progression—A Comprehensive and Critical Review. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010036

Chicago/Turabian StyleDogani Rodrigues, Victória, Mayara Longui Cabrini, Eliana de Souza Bastos Mazuqueli Pereira, Manuela dos Santos Bueno, Virgínia Maria Catharin, Jesselina Francisco dos Santos Haber, Rachel Gomes Eleutério, Lidiane Indiani, Vitor Cavallari Strozze Catharin, Raquel Cristina Ferraroni Sanches, and et al. 2026. "Ligustilide: A Phytochemical with Potential in Combating Cancer Development and Progression—A Comprehensive and Critical Review" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010036

APA StyleDogani Rodrigues, V., Longui Cabrini, M., de Souza Bastos Mazuqueli Pereira, E., dos Santos Bueno, M., Catharin, V. M., dos Santos Haber, J. F., Gomes Eleutério, R., Indiani, L., Cavallari Strozze Catharin, V., Cristina Ferraroni Sanches, R., Cristina Castilho Carácio, F., Lais Menegucci Zutin, T., Engrácia Valenti, V., Barbalho, S. M., & Laurindo, L. F. (2026). Ligustilide: A Phytochemical with Potential in Combating Cancer Development and Progression—A Comprehensive and Critical Review. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010036