Discovery of New Quinazolinone and Benzimidazole Analogs as Tubulin Polymerization Inhibitors with Potent Anticancer Activities

Abstract

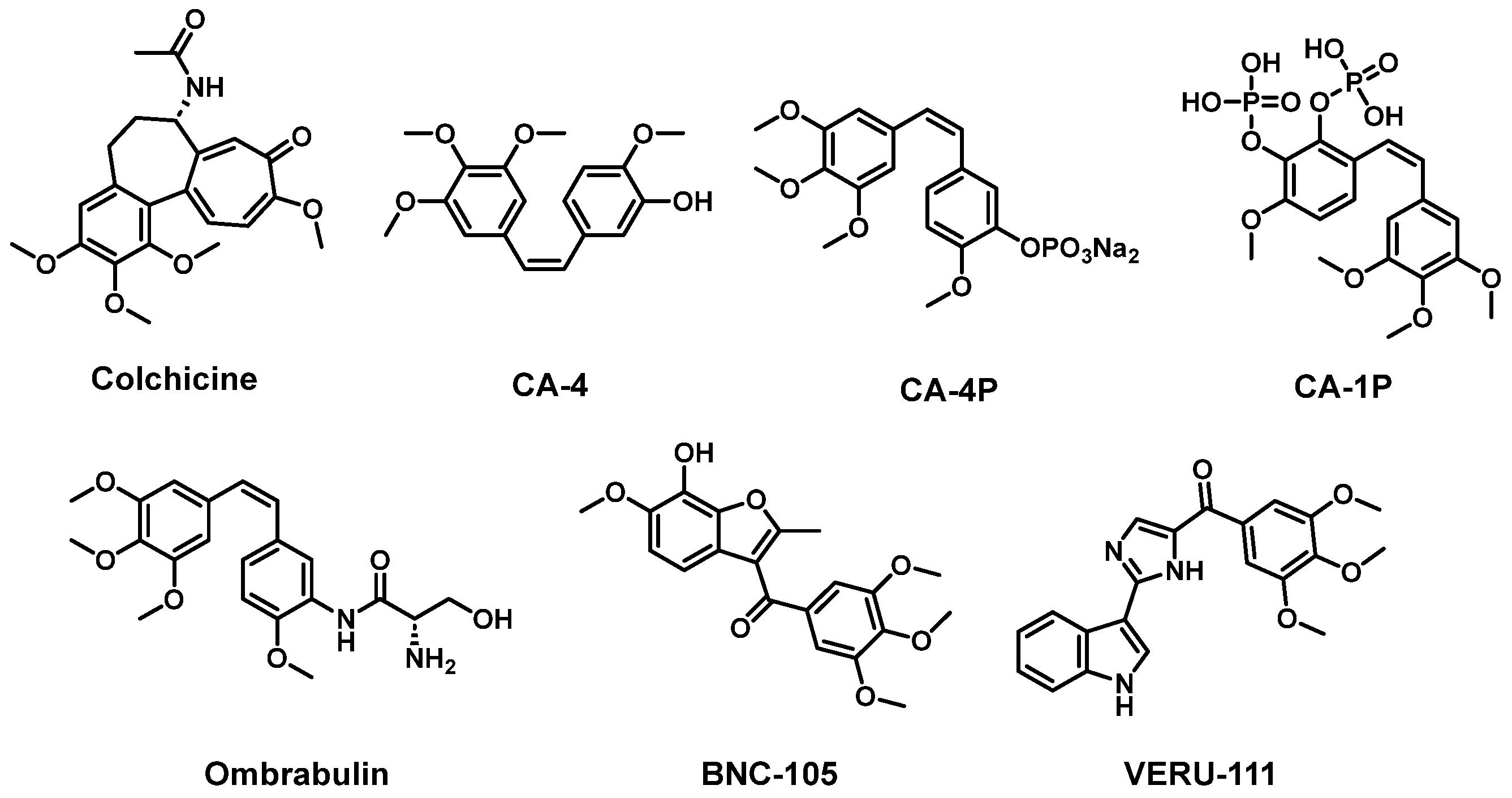

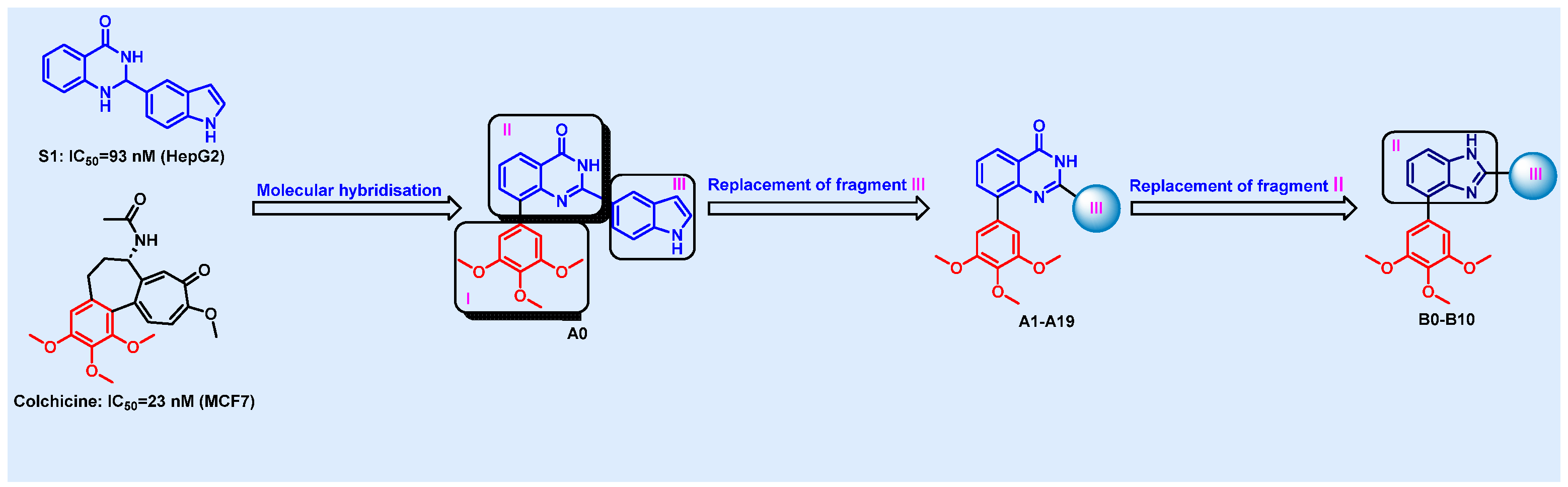

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

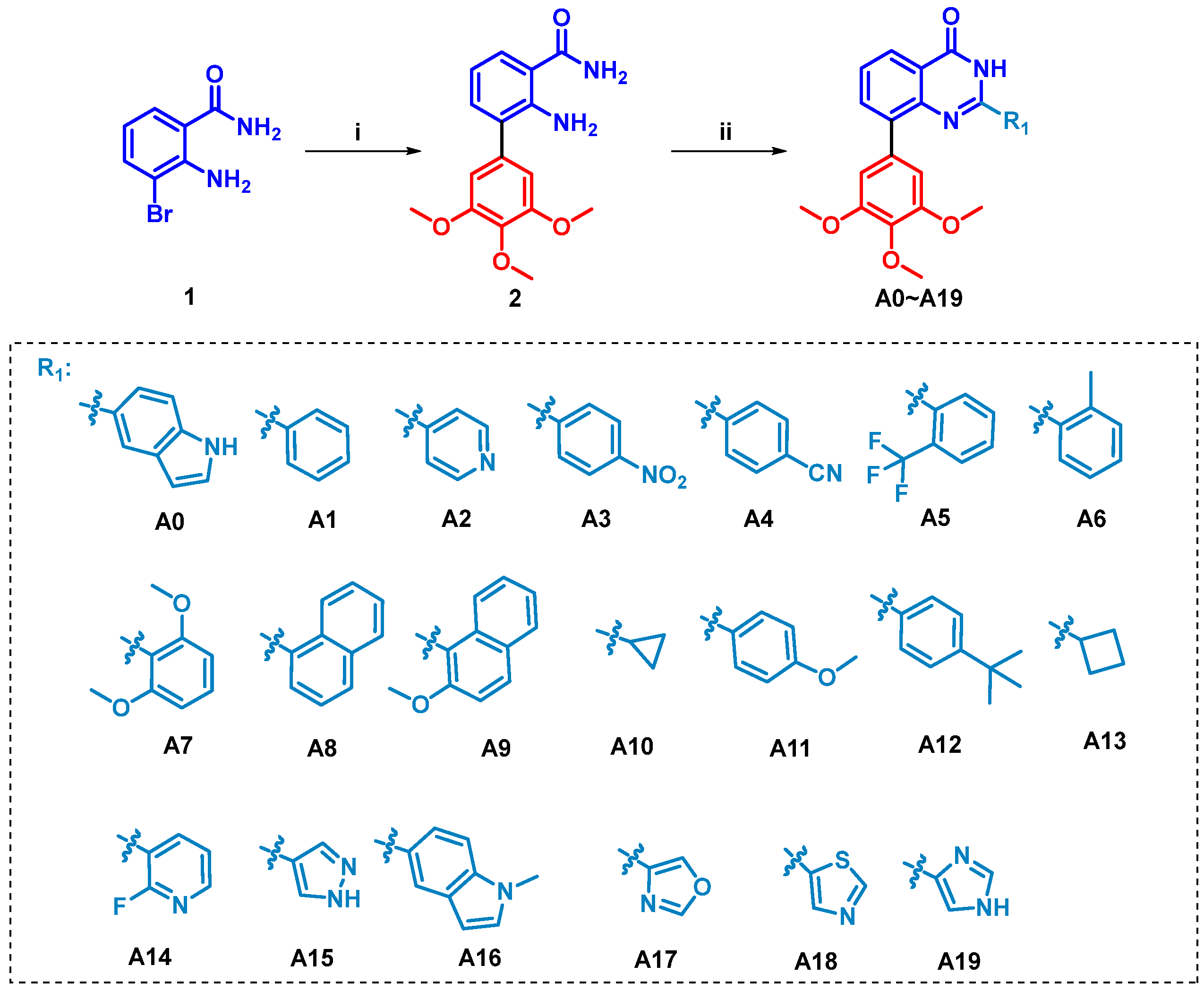

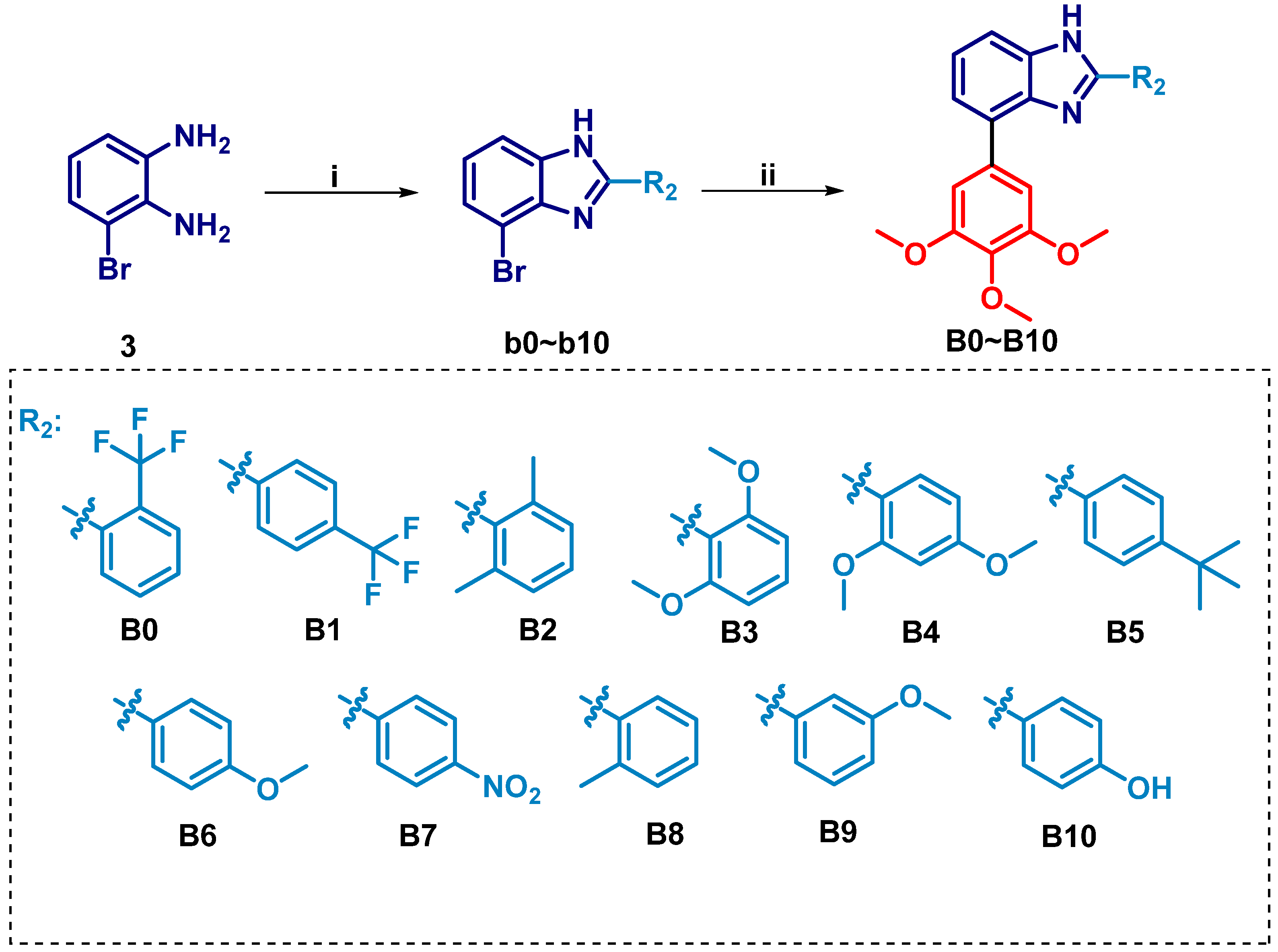

2.1. Chemistry

2.2. Biology

2.2.1. Binding Affinity to Tubulin Protein Analysis

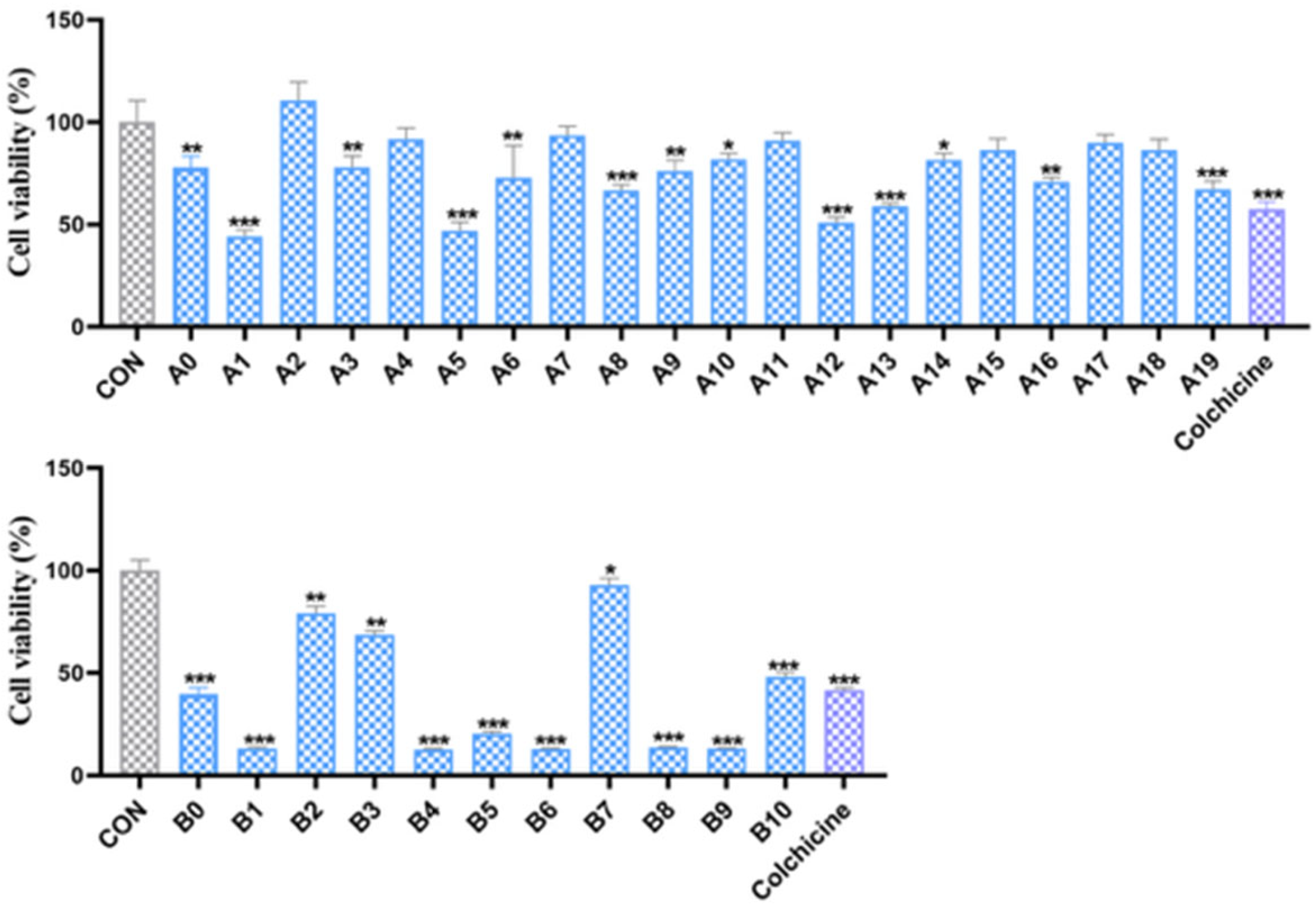

2.2.2. In Vitro Antiproliferative Activity

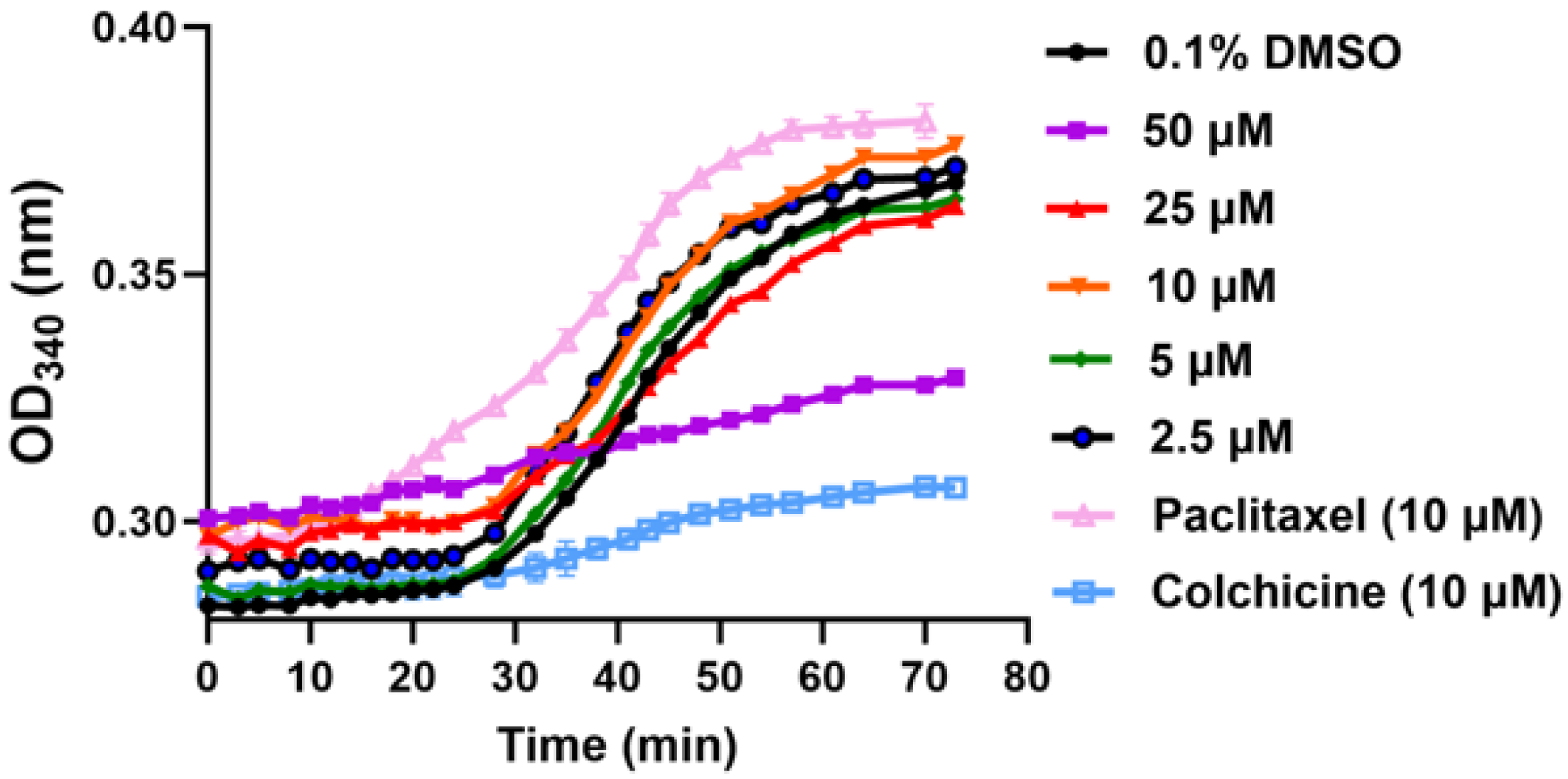

2.2.3. In Vitro Inhibition of Tubulin Polymerization

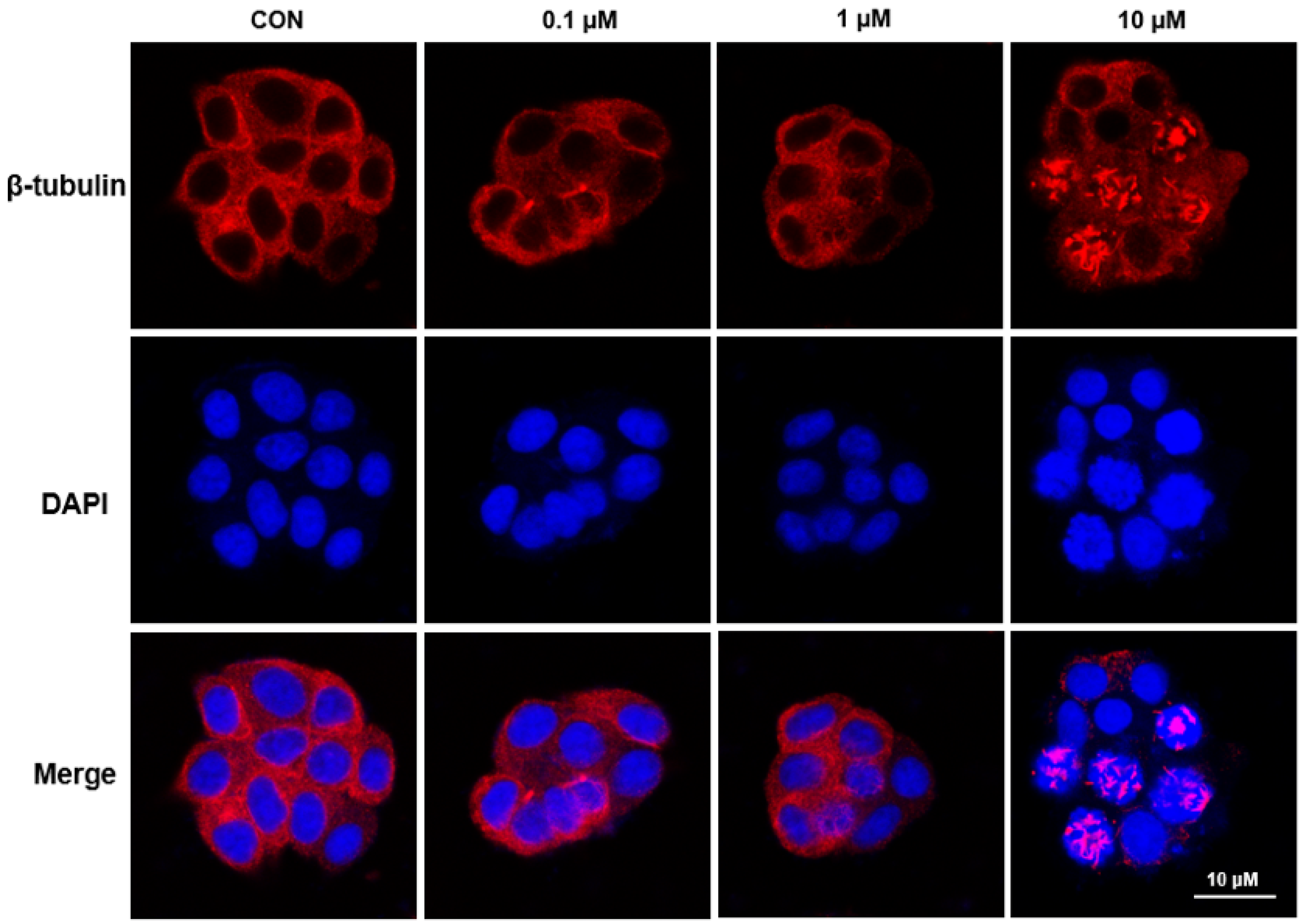

2.2.4. Immunofluorescence Analysis

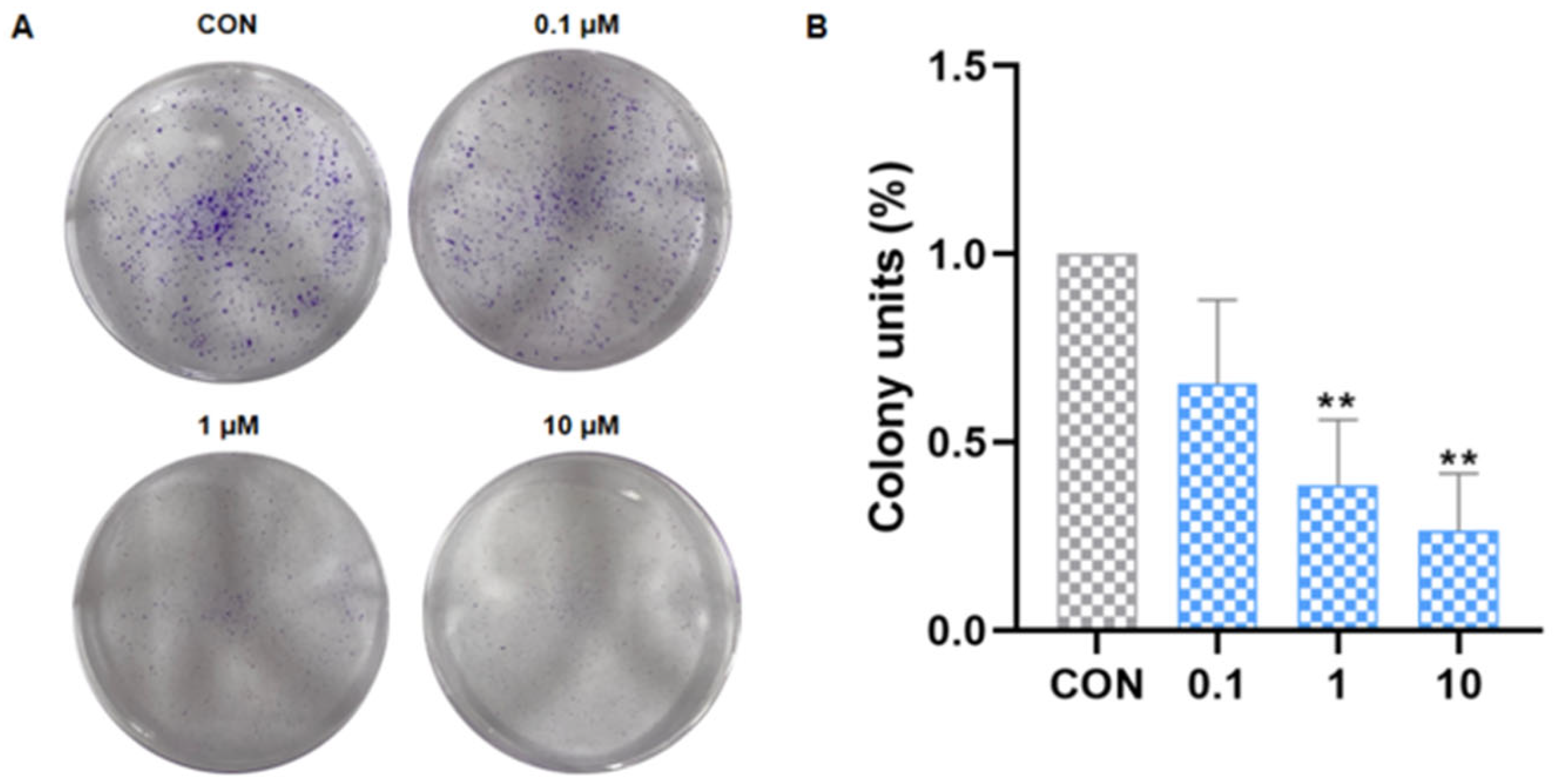

2.2.5. Inhibited the Colony Formation of Cancer Cells

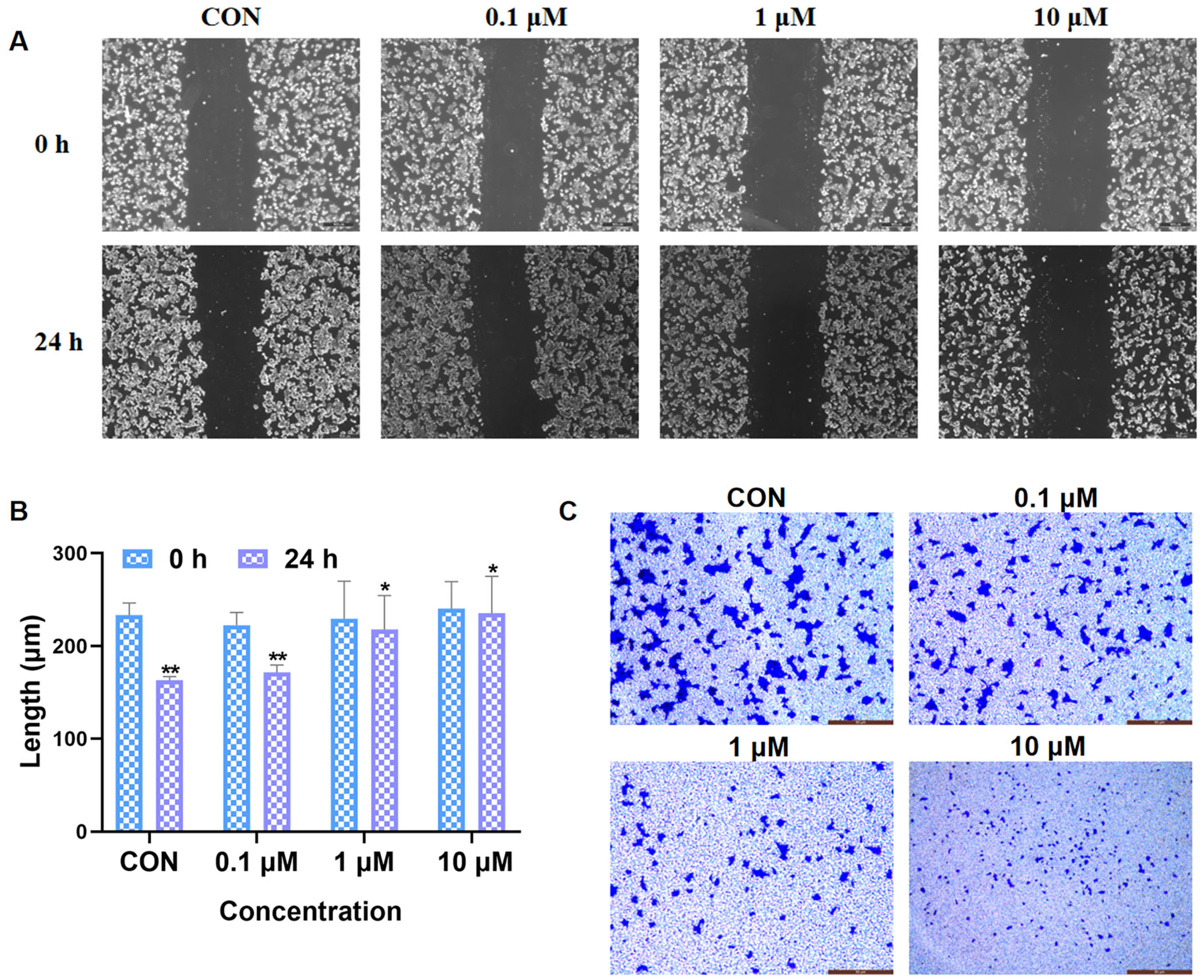

2.2.6. Inhibition of Cancer Cell Migration and Invasion

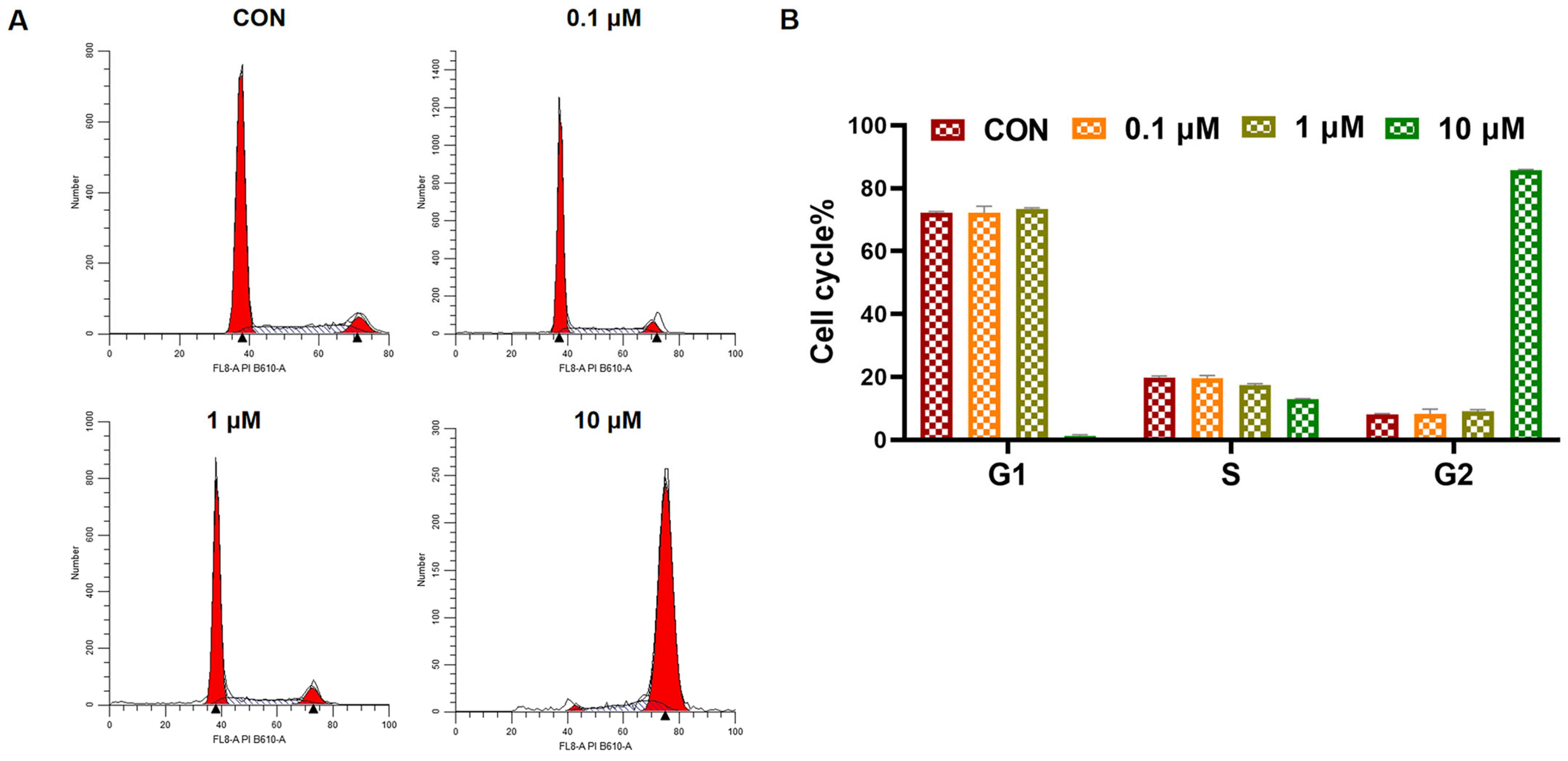

2.2.7. Cell Cycle Analysis

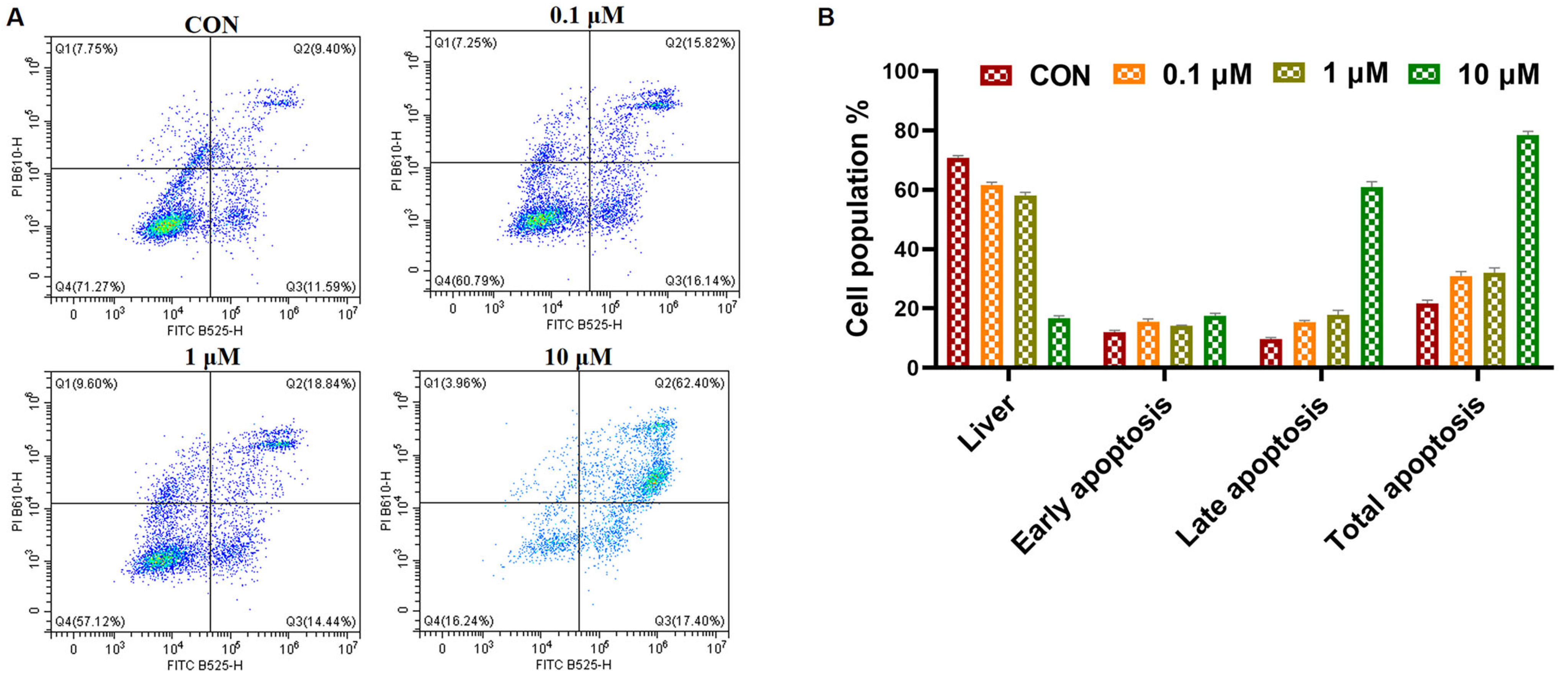

2.2.8. Cell Apoptosis Analysis

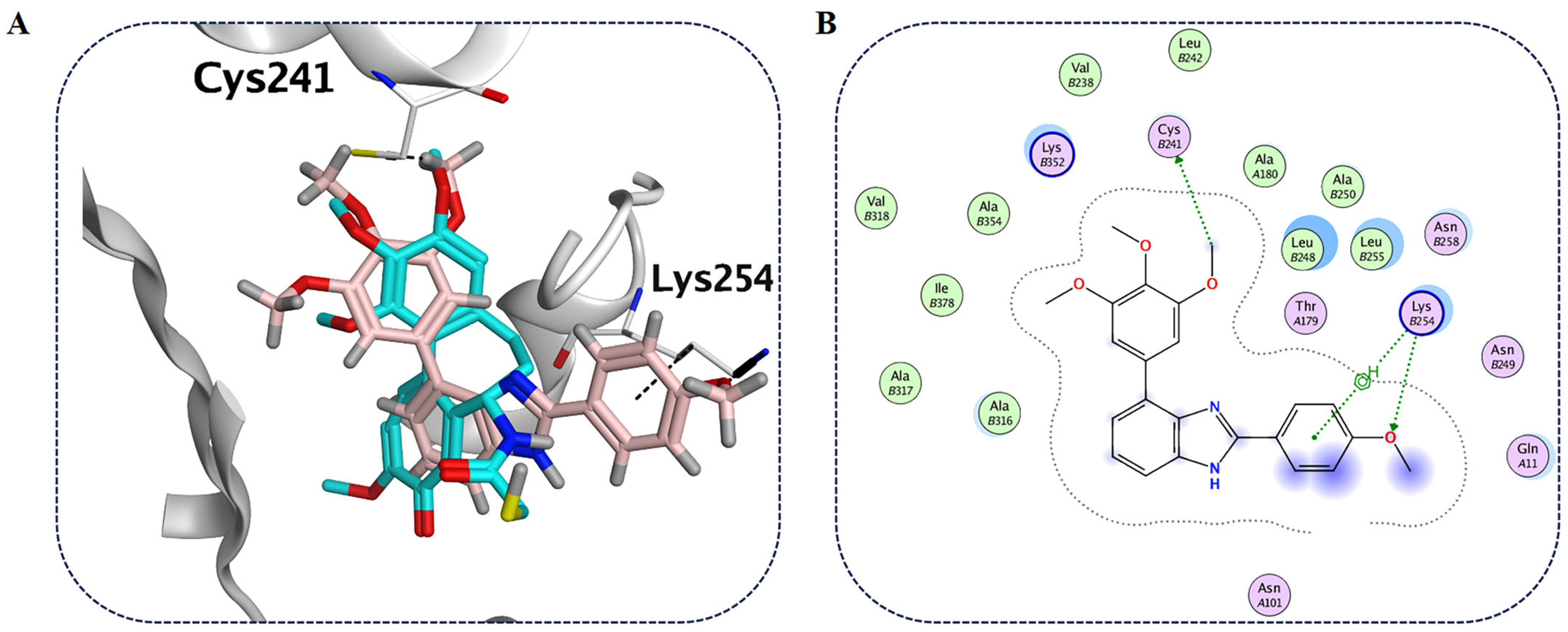

2.2.9. Molecular Modeling Studies with Compound B6 and Tubulin

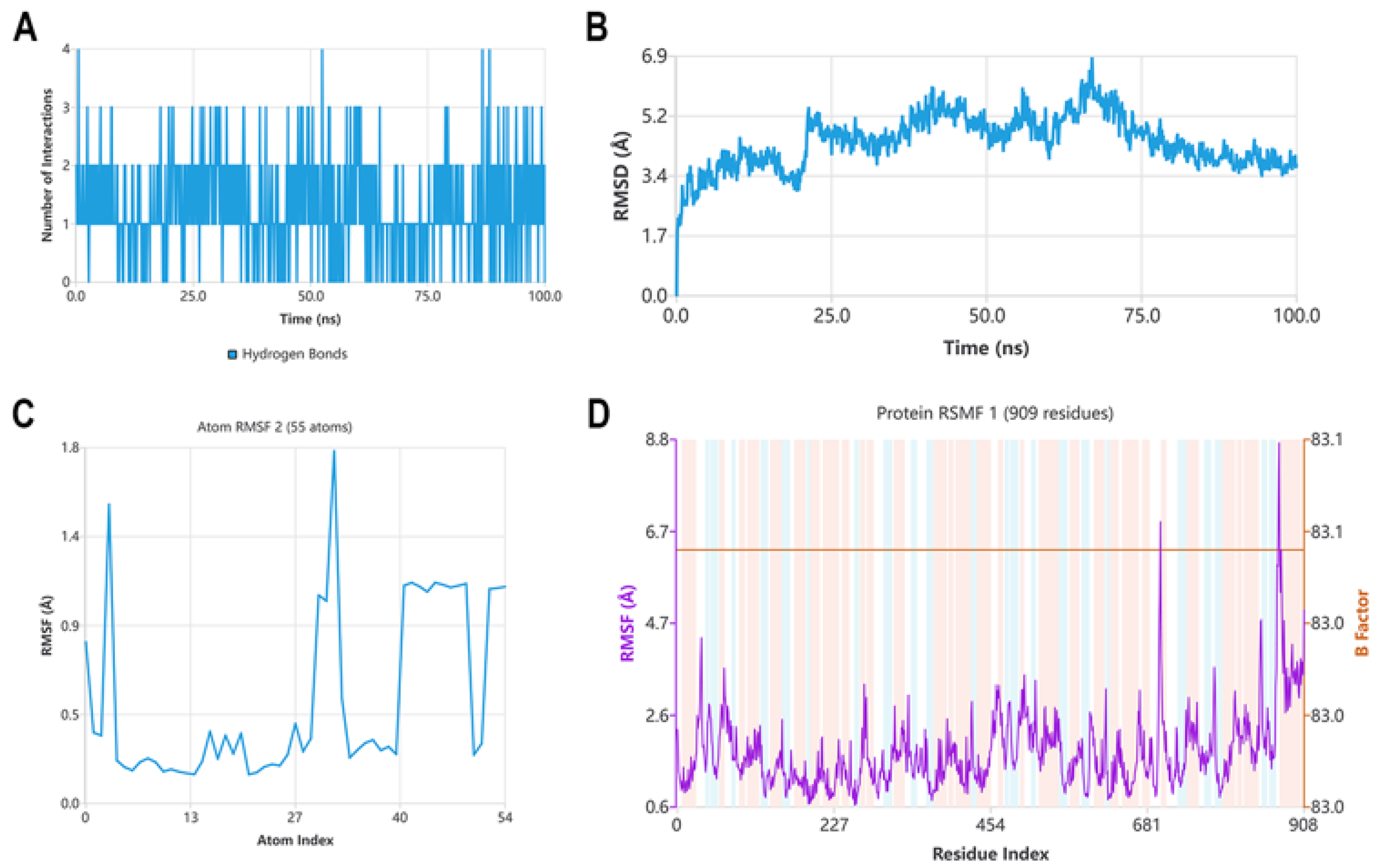

2.2.10. Molecular Dynamics Studies with Compound B6 and Tubulin

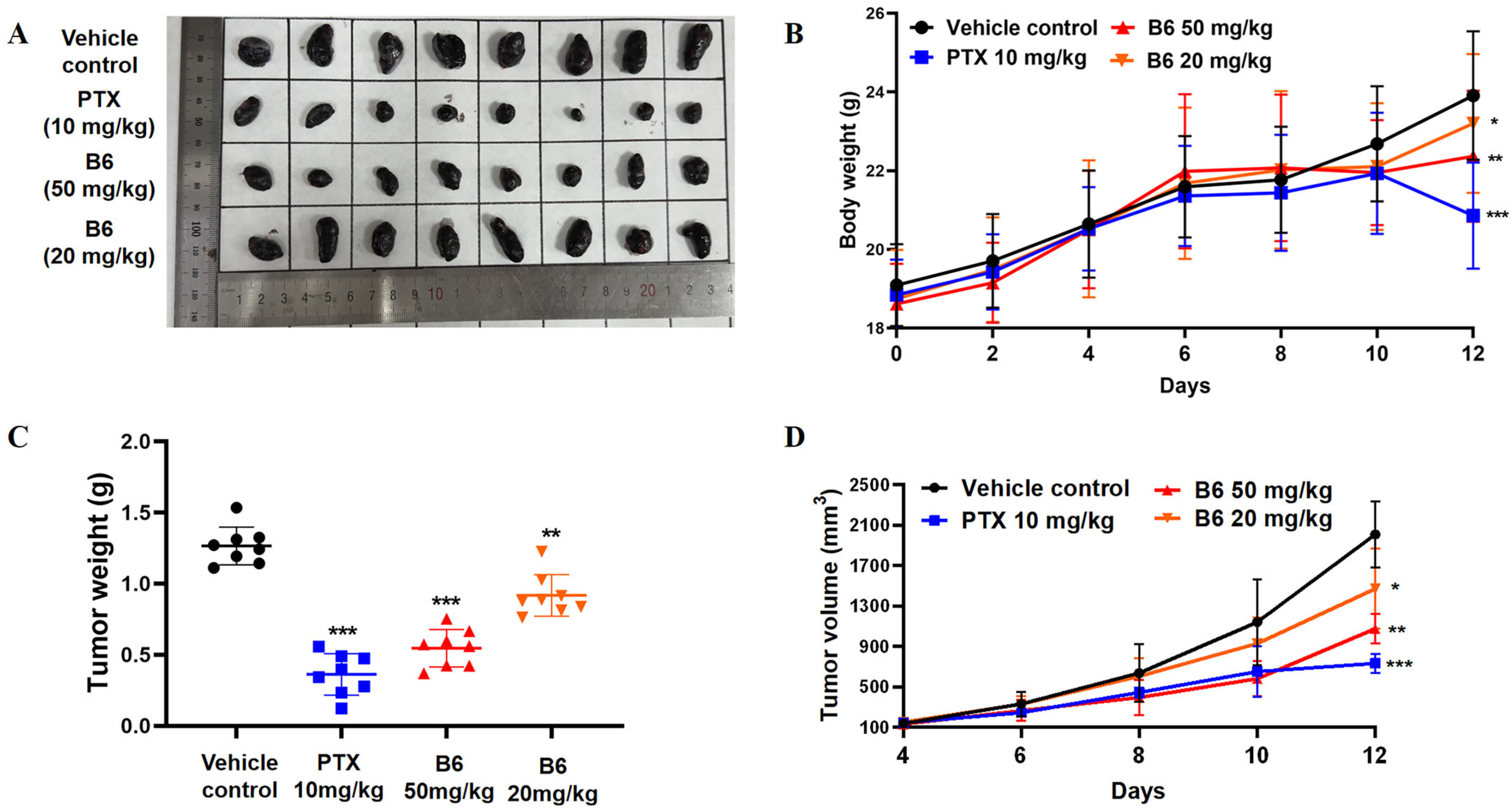

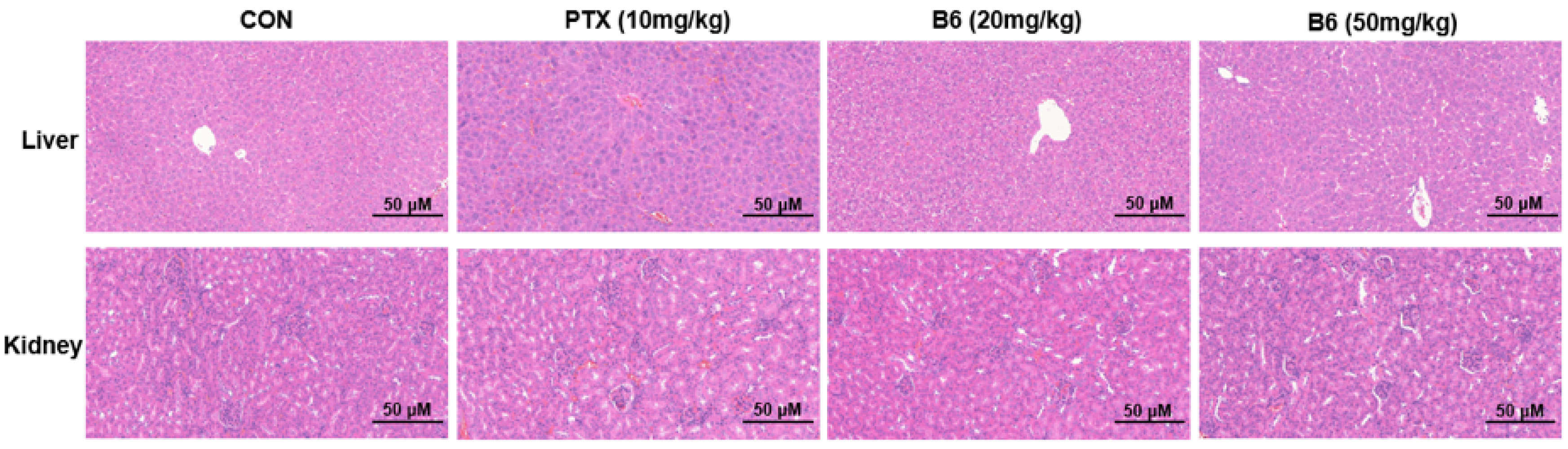

2.2.11. In Vivo Antitumor Efficacy

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Chemistry Methods

3.1.1. General Procedures for the Preparation of Compounds A0–A19

3.1.2. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Intermediates b

3.1.3. General Procedures for the Preparation of Compounds B0–B10

3.2. Biological Evaluation

3.2.1. Bio-Layer Interferometry

3.2.2. Cytotoxicity Assay

3.2.3. In Vitro Tubulin Polymerization Assay

3.2.4. Immunofluorescence Staining

3.2.5. Colony Formation Assay

3.2.6. Transwell Assay

3.2.7. Wound Healing Assay

3.2.8. Analysis of Cell Cycle

3.2.9. Analysis of Cancer Cell Apoptosis

3.2.10. Molecular Docking

3.2.11. Molecular Dynamics Studies

3.2.12. In Vivo Antitumor Evaluation

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jiramongkol, Y.; Lam, E.W.F. FOXO transcription factor family in cancer and metastasis. Cancer Metast. Rev. 2020, 39, 681–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattiuzzi, C.; Lippi, G. Current cancer epidemiology. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2019, 9, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, H.; Kim, Y.H. Cancer prevention from the perspective of global cancer burden patterns. J. Thorac. Dis. 2017, 9, 448–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA-Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA-Cancer J Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogales, E. Structural insights into microtubule function. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000, 69, 277–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Lu, X.; Feng, B. A review of research progress of antitumor drugs based on tubulin targets. Transl. Cancer Res. 2020, 9, 4020–4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Kaur, G.; Gill, R.K.; Soni, R.; Bariwal, J. Recent developments in tubulin polymerization inhibitors: An overview. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 87, 89–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmanova, A.; Steinmetz, M.O. Control of microtubule organization and dynamics: Two ends in the limelight. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 16, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wordeman, L.; Vicente, J.J. Microtubule targeting agents in disease: Classic drugs, novel roles. Cancers 2021, 13, 5650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.; Zhao, Y.; Sheng, P.; Xia, Y.; Chen, T.; Zhao, S.; Xie, S.; Yan, X.; Wang, X.; Yin, Y.; et al. Discovery of novel N-Heterocyclic-Fused deoxypodophyllotoxin analogues as tubulin polymerization inhibitors targeting the colchicine-binding site for cancer treatment. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 16774–16800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuai, W.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Bu, F.; Zhang, S.; Miller, D.D.; Li, W.; Ouyang, L.; Wang, Y. Recent progress on tubulin inhibitors with dual targeting capabilities for cancer therapy. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 7963–7990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, L.M.; O’Boyle, N.M.; Nolan, D.P.; Meegan, M.J.; Zisterer, D.M. The vascular targeting agent Combretastatin-A4 directly induces autophagy in adenocarcinoma-derived colon cancer cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012, 84, 612–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Sun, L.; Gu, Y.; Hu, L. Synthesis and structure-activity relationship study of water-soluble carbazole sulfonamide derivatives as new anticancer agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 191, 112181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujade-Lauraine, E.; Vergote, I.B.; Allard, A.; Rey, A.A.; Sessa, C.; Birrer, M.J. Opsalin: A phase II placebo-controlled randomized study of ombrabulin in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer treated with carboplatin (Cb) and paclitaxel (P). J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uckun, F.M.; Cogle, C.R.; Lin, T.L.; Qazi, S.; Trieu, V.N.; Schiller, G.; Watts, J.M. A Phase 1B clinical study of combretastatin A1 Diphosphate (OXi4503) and Cytarabine (ARA-C) in Combination (OXA) for patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Cancers 2020, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wu, C.; Wang, C.; Zhang, G.; Arnst, K.E.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Pu, D.; Li, W. Unraveling the molecular mechanism of BNC105, a phase II clinical trial vascular disrupting agent, provides insights into drug design. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 525, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Krutilina, R.; Wang, Q.; Lin, Z.; Parke, D.; Playa, H.; Chen, H.; Miller, D.; Seagroves, T.; Li, W. An orally available tubulin inhibitor, VERU-111, suppresses triple-negative breast cancer tumor growth and metastasis and bypasses taxane resistance. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2020, 19, 348–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, E.; Khajouei, M.R.; Hassanzadeh, F.; Hakimelahi, G.H.; Khodarahmi, G.A. Quinazolinone and quinazoline derivatives: Recent structures with potent antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, C.; Yang, B.; He, Z.; Yang, J.; Li, L.; Song, J.; Xu, S.; Song, W.; Yang, J. Discovery of novel 2-substituted 2, 3-dihydroquinazolin-4(1H)-one derivatives as tubulin polymerization inhibitors for anticancer therapy: The in vitro and in vivo biological evaluation. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 277, 116766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segaoula, Z.; Leclercq, J.; Verones, V.; Flouquet, N.; Lecoeur, M.; Ach, L.; Renault, N.; Barczyk, A.; Melnyk, P.; Berthelot, P.; et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of N-[2-(4-Hydroxyphenylamino)-pyridin-3-yl]-4-methoxy-benzenesulfonamide (ABT-751) tricyclic analogues as antimitotic and antivascular agents with potent in vivo antitumor activity. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 8422–8440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dohle, W.; Jourdan, F.L.; Menchon, G.; Prota, A.E.; Foster, P.A.; Mannion, P.; Hamel, E.; Thomas, M.P.; Kasprzyk, P.G.; Ferrandis, E.; et al. Quinazolinone-based anticancer agents: Synthesis, antiproliferative SAR, antitubulin activity, and tubulin co-crystal structure. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 1031–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonawane, V.; Mohd Siddique, M.U.; Jadav, S.S.; Sinha, B.N.; Jayaprakash, V.; Chaudhuri, B. Cink4T, a quinazolinone-based dual inhibitor of Cdk4 and tubulin polymerization, identified via ligand-based virtual screening, for efficient anticancer therapy. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 165, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Li, C.-M.; Ahn, S.; Barrett, C.M.; Dalton, J.T.; Li, W.; Miller, D.D. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Stable Colchicine Binding Site Tubulin Inhibitors as Potential Anticancer Agents. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 7355–7366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravelli, R.B.; Gigant, B.; Curmi, P.A.; Jourdain, I.; Lachkar, S.; Sobel, A.; Knossow, M. Insight into tubulin regulation from a complex with colchicine and a stathmin-like domain. Nature 2004, 428, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, H.; Li, J.; Zhu, H.; Carver Wong, K.F.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, J. An update on the recent advances and discovery of novel tubulin colchicine binding inhibitors. Future Med. Chem. 2023, 15, 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnoli, R.; Baraldi, P.G.; Kimatrai Salvador, M.; Preti, D.; Aghazadeh Tabrizi, M.; Bassetto, M.; Brancale, A.; Hamel, E.; Castagliuolo, I.; Bortolozzi, R.; et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 2-(alkoxycarbonyl)-3-anilinobenzo[b]thiophenes and thieno[2,3-b]pyridines as new potent anticancer agents. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 2606–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddyrajula, R.; Kathirvel, P.V.; Shankaraiah, N. Recent developments of benzimidazole based analogs as potential tubulin polymerization inhibitors: A critical review. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2025, 122, 130167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wolfe, A.; Brooks, J.; Zhu, Z.-Q.; Li, J. Modifying emission spectral bandwidth of phosphorescent platinum(II) complexes through synthetic control. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 8244–8256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, D.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, J. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of dual mTOR/HDAC6 inhibitors in MDA-MB-231 cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 47, 128204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yang, M.; Wen, Z.; Mei, F.; Chen, Q.; Ma, Y.; Lai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, R.; Yin, T.; et al. Trametinib and M17, a novel small molecule inhibitor of AKT, display a synergistic antitumor effect in triple negative breast cancer cells through the AKT/mTOR and MEK/ERK pathways. Bioorg. Chem. 2025, 154, 107981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanaussavadate, B.; Ngiwsara, L.; Lirdprapamongkol, K.; Svasti, J.; Chuawong, P. A synthetic 2,3-diarylindole induces microtubule destabilization and G2/M cell cycle arrest in lung cancer cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 30, 126777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, K.J.; Chow, E.; Xu, H.; Dror, R.O.; Eastwood, M.P.; Gregersen, B.A.; Klepeis, J.L.; Kolossvary, I.; Moraes, M.A.; Sacerdoti, F.D.; et al. Scalable algorithms for molecular dynamics simulations on commodity clusters. In Proceedings of the SC ’06: International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis, Tampa, FL, USA, 11–17 November 2006; p. 84-es. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Wu, C.; Ghoreishi, D.; Chen, W.; Wang, L.; Damm, W.; Ross, G.A.; Dahlgren, M.K.; Russell, E.; Von Bargen, C.D.; et al. OPLS4: Improving Force Field Accuracy on Challenging Regimes of Chemical Space. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 4291–4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compounds | KD (μM) | Compounds | KD (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colchicine | 3.30 ± 1.20 | A15 | 1.90 ± 0.60 |

| A0 | 10.6 ± 1.80 | A16 | ND |

| A1 | 7.50 ± 2.00 | A17 | 8.90 ± 1.00 |

| A2 | 22.00 ± 3.60 | A18 | 3.30 ± 0.70 |

| A3 | 16.00 ± 1.80 | A19 | 9.20 ± 1.60 |

| A4 | 1.40 ± 1.00 | B0 | 4.20 ± 1.02 |

| A5 | 0.72 ± 0.80 | B1 | 12.00 ± 1.20 |

| A6 | 4.90 ± 1.70 | B2 | NB |

| A7 | 56.00 ± 3.80 | B3 | 0.58 ± 0.50 |

| A8 | 17.00 ± 2.40 | B4 | 2.20 ± 1.10 |

| A9 | 3.70 ± 2.70 | B5 | 2.90 ± 1.00 |

| A10 | NB | B6 | 0.27 ± 0.30 |

| A11 | 79.00 ± 2.30 | B7 | 14.00 ± 1.60 |

| A12 | ND | B8 | 7.50 ± 0.80 |

| A13 | 22.00 ± 1.10 | B9 | 9.70 ± 1.20 |

| A14 | 13.00 ± 1.90 | B10 | 3.50 ± 0.90 |

| Compounds | Structure of Fragment III | MCF-7 | MDA-MB-231 | A549 | Hela |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50/μM | IC50/μM | IC50/μM | IC50/μM | ||

| B1 |  | 3.80 ± 1.40 | 12.10 ± 1.50 | 2.40 ± 1.10 | 3.60 ± 0.80 |

| B4 |  | 7.60 ± 1.10 | 23.20 ± 1.10 | 4.80 ± 1.00 | 5.10 ± 1.20 |

| B5 |  | 6.60 ± 1.20 | 17.20 ± 1.20 | 9.60 ± 1.50 | 4.10 ± 1.40 |

| B6 |  | 1.40 ± 0.90 | 2.50 ± 0.70 | 1.80 ± 0.60 | 1.80 ± 1.10 |

| B8 |  | 4.20 ± 0.90 | 12.60 ± 1.20 | 5.80 ± 1.10 | 4.40 ± 0.90 |

| B9 |  | 3.60 ± 1.20 | 7.80 ± 0.90 | 5.50 ± 1.20 | 3.60 ± 0.90 |

| B10 |  | 32.30 ± 1.70 | 41.90 ± 1.70 | 17.30 ± 1.40 | 24.90 ± 1.50 |

| Colchicine | / | 0.023 ± 0.0090 | 0.022 ± 0.0060 | 0.080 ± 0.010 | 0.004 ± 0.0040 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jiang, B.; Zhang, J.; Shao, K.; Gai, C.; Xu, B.; Zou, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Meng, Q.; Chai, X. Discovery of New Quinazolinone and Benzimidazole Analogs as Tubulin Polymerization Inhibitors with Potent Anticancer Activities. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010161

Jiang B, Zhang J, Shao K, Gai C, Xu B, Zou Y, Song Y, Zhao Q, Meng Q, Chai X. Discovery of New Quinazolinone and Benzimidazole Analogs as Tubulin Polymerization Inhibitors with Potent Anticancer Activities. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010161

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Boye, Juan Zhang, Kai Shao, Conghao Gai, Bing Xu, Yan Zou, Yan Song, Qingjie Zhao, Qingguo Meng, and Xiaoyun Chai. 2026. "Discovery of New Quinazolinone and Benzimidazole Analogs as Tubulin Polymerization Inhibitors with Potent Anticancer Activities" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010161

APA StyleJiang, B., Zhang, J., Shao, K., Gai, C., Xu, B., Zou, Y., Song, Y., Zhao, Q., Meng, Q., & Chai, X. (2026). Discovery of New Quinazolinone and Benzimidazole Analogs as Tubulin Polymerization Inhibitors with Potent Anticancer Activities. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010161