Hitting the Target: Model-Informed Precision Dosing of Tobramycin in Pediatric Patients with Cystic Fibrosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Patients

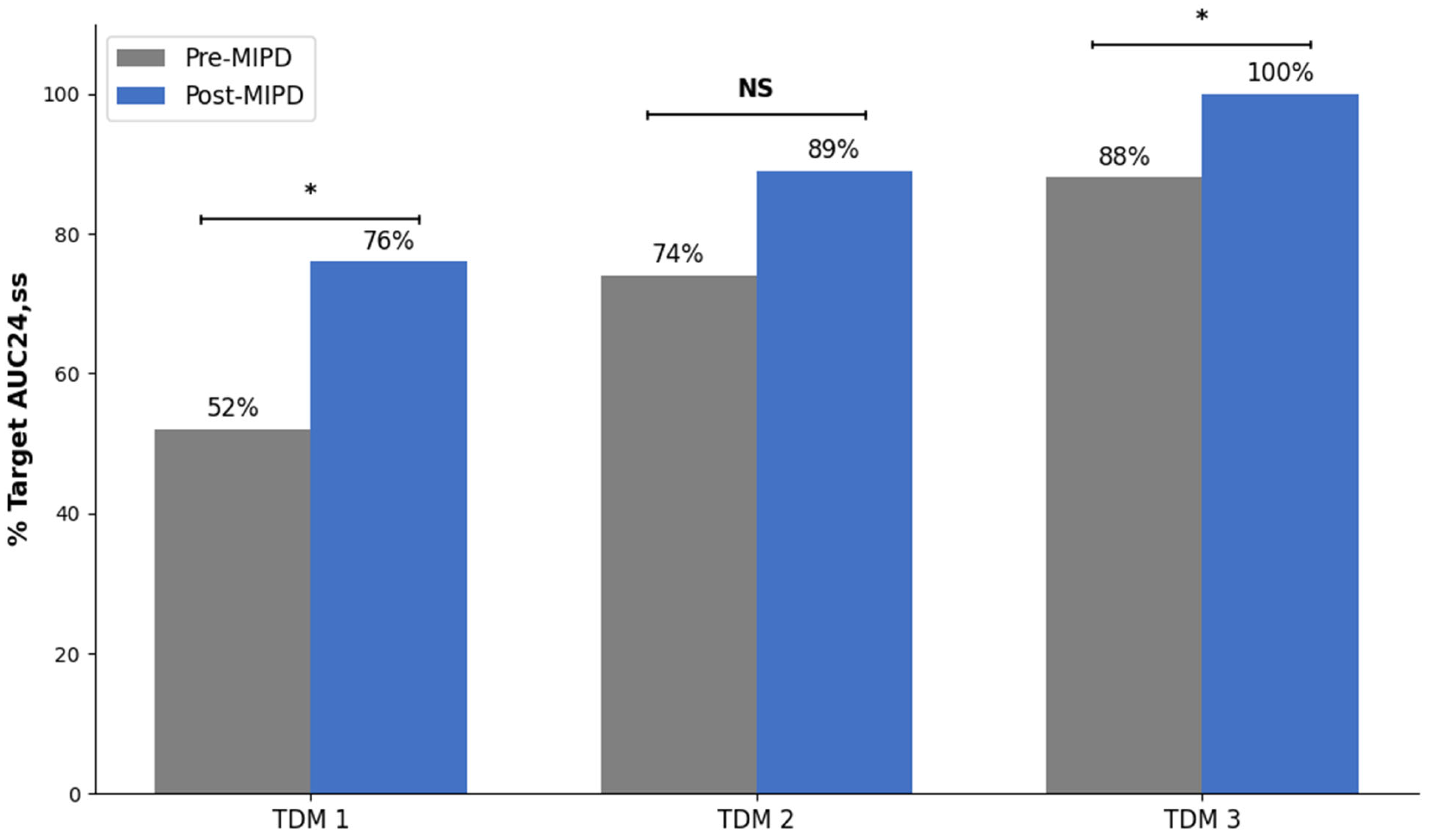

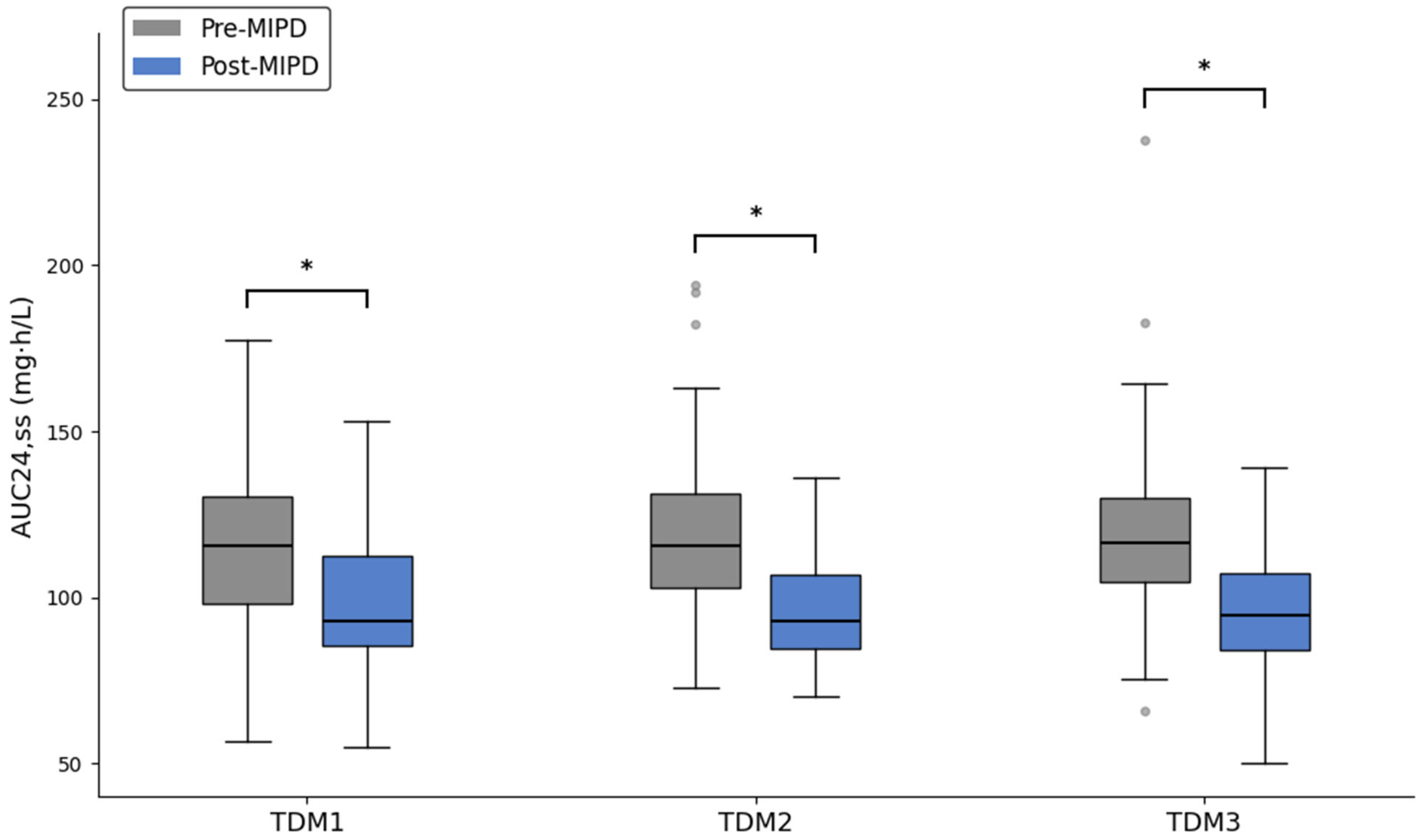

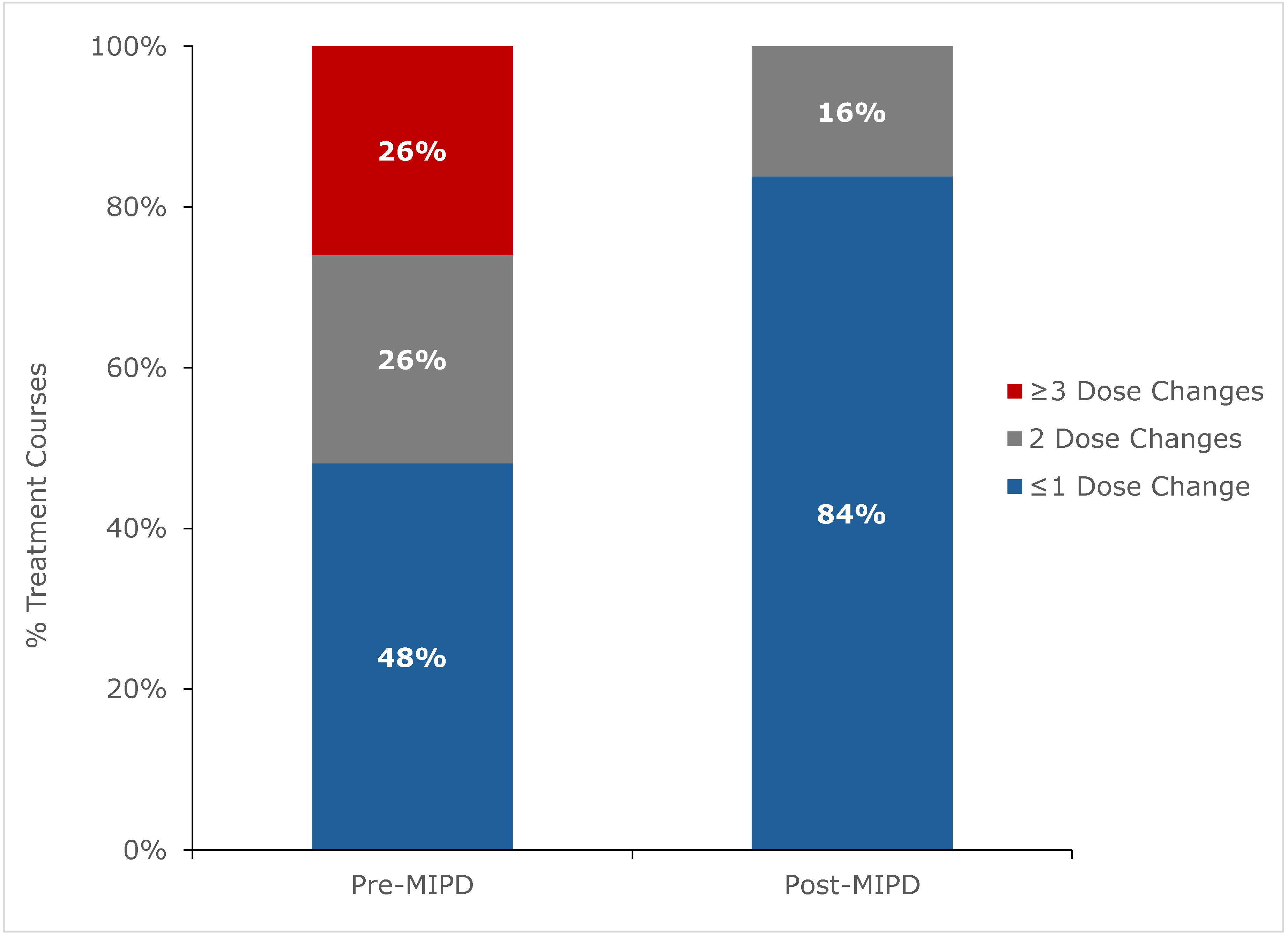

2.2. Outcomes

3. Discussion

4. Methods

4.1. Patient Population

4.2. Pre-MIPD Period

4.3. Post-MIPD Period

4.4. Study Data and Outcomes

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AKI | acute kidney injury |

| AUC | area under the concentration-time curve |

| AUC24 | area under the concentration-time curve over 24 h |

| AUC24,ss | area under the concentration-time curve over 24 h at steady state |

| BMI | body mass index |

| CDS | clinical decision support |

| CF | cystic fibrosis |

| CFTR | cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator |

| eGFR | estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| EHR | electronic health record |

| KDIGO | Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes |

| MAP | maximum a posteriori |

| MIPD | model-informed precision dosing |

| NINJA | Nephrotoxic Injury Negated by Just-in-Time Action |

| PK | pharmacokinetics |

| SCr | serum creatinine |

| TDM | therapeutic drug monitoring |

References

- Flume, P.A.; Mogayzel, P.J.; Robinson, K.A.; Goss, C.H.; Rosenblatt, R.L.; Kuhn, R.J.; Marshall, B.C. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pulmonary Therapies Committee. Cystic Fibrosis Pulmonary Guidelines: Treatment of Pulmonary Exacerbations. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 180, 802–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, A.; Tan, K.H.V.; Hyman-Taylor, P.; Mulheran, M.; Lewis, S.; Stableforth, D.; Knox, A.; TOPIC Study Group. Once versus three-times daily regimens of tobramycin treatment for pulmonary exacerbations of cystic fibrosis--the TOPIC study: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005, 365, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, J.; Jahnke, N.; Smyth, A.R. Once-daily versus multiple-daily dosing with intravenous aminoglycosides for cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 9, CD002009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arends, A.; Pettit, R. Safety of Extended Interval Tobramycin in Cystic Fibrosis Patients Less Than 6 Years Old. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 23, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, K.J.; Grim, A.; Shanley, L.; Rubenstein, R.C.; Zuppa, A.F.; Gastonguay, M.R. A Pharmacokinetic Analysis of Tobramycin in Patients Less than Five Years of Age with Cystic Fibrosis: Assessment of Target Attainment with Extended-Interval Dosing through Simulation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e0237721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imburgia, T.A.; Seagren, R.M.; Christensen, H.; Lasarev, M.R.; Bogenschutz, M.C. Review of Tobramycin Dosing in Pediatric Patients With Cystic Fibrosis. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. JPPT Off. J. PPAG 2023, 28, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harwood, K.H.; Duffull, S.; Shanthikumar, S.; Lei, A.; Ranganathan, S.; Robinson, P.; Sandaradura, I.; Lai, T.; Gwee, A. Personalized tobramycin dosing in children with cystic fibrosis: An AUC24-guided approach. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2025, 69, e0027825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennig, S.; Standing, J.F.; Staatz, C.E.; Thomson, A.H. Population Pharmacokinetics of Tobramycin in Patients With and Without Cystic Fibrosis. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2013, 52, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouton, J.W.; Jacobs, N.; Tiddens, H.; Horrevorts, A.M. Pharmacodynamics of tobramycin in patients with cystic fibrosis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2005, 52, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt, O.; Lehmann, C.; Madabushi, R.; Kumar, V.; Derendorf, H.; Welte, T. Once-daily tobramycin in cystic fibrosis: Better for clinical outcome than thrice-daily tobramycin but more resistance development? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 58, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashiguchi, Y.; Matsumoto, N.; Oda, K.; Jono, H.; Saito, H. Population Pharmacokinetics and AUC-Guided Dosing of Tobramycin in the Treatment of Infections Caused by Glucose-Nonfermenting Gram-Negative Bacteria. Clin. Ther. 2023, 45, 400–414.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paviour, S.; Hennig, S.; Staatz, C.E. Usage and monitoring of intravenous tobramycin in cystic fibrosis in Australia and the UK. J. Pharm. Pr. Res. 2016, 46, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drusano, G.L.; Louie, A. Optimization of aminoglycoside therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 2528–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pai, M.P.; Neely, M.; Rodvold, K.A.; Lodise, T.P. Innovative approaches to optimizing the delivery of vancomycin in individual patients. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2014, 77, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockmeyer, J.M.; Wise, R.T.; Burgener, E.B.; Milla, C.; Frymoyer, A. Area under the curve achievement of once daily tobramycin in children with cystic fibrosis during clinical care. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2020, 55, 3343–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinks, A.A.; Peck, R.W.; Neely, M.; Mould, D.R. Development and Implementation of Electronic Health Record-Integrated Model-Informed Clinical Decision Support Tools for the Precision Dosing of Drugs. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 107, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwich, A.S.; Polasek, T.M.; Aronson, J.K.; Ogungbenro, K.; Wright, D.F.B.; Achour, B.; Reny, J.-L.; Daali, Y.; Eiermann, B.; Cook, J.; et al. Model-Informed Precision Dosing: Background, Requirements, Validation, Implementation, and Forward Trajectory of Individualizing Drug Therapy. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2021, 61, 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frymoyer, A.; Schwenk, H.T.; Zorn, Y.; Bio, L.; Moss, J.D.; Chasmawala, B.; Faulkenberry, J.; Goswami, S.; Keizer, R.J.; Ghaskari, S. Model-Informed Precision Dosing of Vancomycin in Hospitalized Children: Implementation and Adoption at an Academic Children’s Hospital. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Valle-Moreno, P.; Suarez-Casillas, P.; Mejías-Trueba, M.; Ciudad-Gutiérrez, P.; Guisado-Gil, A.B.; Gil-Navarro, M.V.; Herrera-Hidalgo, L. Model-Informed Precision Dosing Software Tools for Dosage Regimen Individualization: A Scoping Review. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frymoyer, A.; Schwenk, H.T.; Brockmeyer, J.M.; Bio, L. Impact of model-informed precision dosing on achievement of vancomycin exposure targets in pediatric patients with cystic fibrosis. Pharmacotherapy 2023, 432, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, C.H.; Heltshe, S.L.; West, N.E.; Skalland, M.; Sanders, D.B.; Jain, R.; Barto, T.L.; Fogarty, B.; Marshall, B.C.; VanDevanter, D.R.; et al. A Randomized Clinical Trial of Antimicrobial Duration for Cystic Fibrosis Pulmonary Exacerbation Treatment. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 204, 1295–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bio, L.; Gaskari, S.; Schwenk, H.T.; Moss, J.; Frymoyer, A. Implementation of the VancomycIn per Pharmacy Education tRaining (VIPER) program for pharmacists at a children’s hospital. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2026, 83, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, C.D.; Nicolau, D.P.; Belliveau, P.P.; Nightingale, C.H. Once-daily dosing of aminoglycosides: Review and recommendations for clinical practice. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1997, 39, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, J.; Smith, A.L.; Koup, J.R.; Williams-Warren, J.; Ramsey, B. Disposition of tobramycin in patients with cystic fibrosis: A prospective controlled study. J. Pediatr. 1984, 105, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sutter, P.; Van Haeverbeke, M.; Van Braeckel, E.; Van Biervliet, S.; Van Bocxlaer, J.; Vermeulen, A.; Gasthuys, E. Altered intravenous drug disposition in people living with cystic fibrosis: A meta-analysis integrating top-down and bottom-up data. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2022, 11, 951–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagnola, E.; Cangemi, G.; Mesini, A.; Castellani, C.; Martelli, A.; Cattaneo, D.; Mattioli, F. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antibiotics in cystic fibrosis: A narrative review. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2021, 58, 106381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beringer, P.M.; Vinks, A.A.; Jelliffe, R.W.; Shapiro, B.J. Pharmacokinetics of tobramycin in adults with cystic fibrosis: Implications for once-daily administration. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 809–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmann, B.; Woods, E.; Makhlouf, T.; Gillette, C.; Perry, C.; Subramanian, M.; Hanes, H. Impact of Patient-Specific Aminoglycoside Monitoring for Treatment of Pediatric Cystic Fibrosis Pulmonary Exacerbations. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. JPPT 2022, 27, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, K.J.; Patil, N.R.; Rao, M.B.; Koralkar, R.; Harris, W.T.; Clancy, J.P.; Goldstein, S.L.; Askenazi, D.J. Risk factors for acute kidney injury during aminoglycoside therapy in patients with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2015, 30, 1879–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, E.S.; Kurzen, E.A.; Linnemann, R.W.; Shin, H.S. Use of the NINJA (Nephrotoxic Injury Negated by Just-in-Time Action) Program to Identify Nephrotoxicity in Pediatric Patients with Cystic Fibrosis. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. JPPT 2021, 26, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.H.-V.; Mulheran, M.; Knox, A.J.; Smyth, A.R. Aminoglycoside Prescribing and Surveillance in Cystic Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 167, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, A.; Young, M.R.; Studtmann, A.E.; Autry, E.B.; Schadler, A.; Beckman, E.J.; Gardner, B.M.; Wurth, M.A.; Kuhn, R.J. Incidence of nephrotoxicity with prolonged aminoglycoside exposure in patients with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2020, 55, 3384–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibbets, A.C.; Koldeweij, C.; Osinga, E.P.; Scheepers, H.C.J.; de Wildt, S.N. Barriers and Facilitators for Bringing Model-Informed Precision Dosing to the Patient’s Bedside: A Systematic Review. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 117, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claus, B.O.M.; De Smedt, D.; De Cock, P.A. Therapeutic drug monitoring versus Bayesian AUC-based dosing for vancomycin in routine practice: A cost–benefit analysis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2025, 80, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.V.; Fong, G.; Bolaris, M.; Neely, M.; Minejima, E.; Kang, A.; Lee, G.; Gong, C.L. Cost–benefit analysis comparing trough, two-level AUC and Bayesian AUC dosing for vancomycin. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 1346.e1–1346.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zobell, J.T.; Epps, K.; Kittell, F.; Sema, C.; McDade, E.J.; Peters, S.J.; Duval, M.A.; Pettit, R.S. Tobramycin and Beta-Lactam Antibiotic Use in Cystic Fibrosis Exacerbations: A Pharmacist Approach. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. JPPT 2016, 21, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Hennig, S.; Barras, M. Monitoring of Tobramycin Exposure: What is the Best Estimation Method and Sampling Time for Clinical Practice? Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2019, 58, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barras, M.A.; Serisier, D.; Hennig, S.; Jess, K.; Norris, R.L.G. Bayesian Estimation of Tobramycin Exposure in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 6698–6702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pre-MIPD (n = 77) | Post-MIPD (n = 37) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 12.7 ± 5.0 | 13.5 ± 5.2 | NS |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 18.4 ± 3.4 | 18.8 ± 3.8 | NS |

| Female, n (%) | 44 (57%) | 20 (54%) | NS |

| Baseline eGFR a, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 140 ± 55 | 145 ± 54 | NS |

| Duration of therapy, days | 13.5 ± 6.2 | 11 ± 3.5 | NS |

| Concomitant antibiotics b, n (%) | |||

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 53 (69%) | 9 (24%) | <0.001 |

| Cefepime | 12 (16%) | 16 (43%) | 0.002 |

| Ceftazidime | 9 (12%) | 8 (22%) | NS |

| Meropenem | 13 (17%) | 3 (8%) | NS |

| Fluoroquinolone c | 21 (27%) | 5 (14%) | NS |

| Number of concomitant nephrotoxic medications d, n (%) | NS | ||

| 0 | 18 (23%) | 15 (41%) | |

| 1 | 47 (61%) | 17 (46%) | |

| 2 | 11 (14%) | 5 (14%) | |

| 3 | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Brockmeyer, J.M.; Bio, L.; Milla, C.; Frymoyer, A. Hitting the Target: Model-Informed Precision Dosing of Tobramycin in Pediatric Patients with Cystic Fibrosis. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010150

Brockmeyer JM, Bio L, Milla C, Frymoyer A. Hitting the Target: Model-Informed Precision Dosing of Tobramycin in Pediatric Patients with Cystic Fibrosis. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):150. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010150

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrockmeyer, Jake M., Laura Bio, Carlos Milla, and Adam Frymoyer. 2026. "Hitting the Target: Model-Informed Precision Dosing of Tobramycin in Pediatric Patients with Cystic Fibrosis" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010150

APA StyleBrockmeyer, J. M., Bio, L., Milla, C., & Frymoyer, A. (2026). Hitting the Target: Model-Informed Precision Dosing of Tobramycin in Pediatric Patients with Cystic Fibrosis. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010150