Advances in Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Gender and Sex Differences in Biomarkers and Their Perspectives for Novel Biosensing Detection Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Epidemiology and Risk Factors

3. CRC Staging

3.1. Polyps of the Colon

3.2. Adenomatous Polyps

3.3. Tubular Adenomas

3.4. Villous Adenomas

4. Biomarkers of CRC

4.1. Genetic Markers

4.2. Inflammatory Markers

4.3. Sex-Specific Biomarkers

| Biomarker | Biological Role | Sex Association | Age of Diagnosis | CRC Stage Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KDM5D [45] | Y-linked histone demethylase; regulates chromatin and immune evasion | Male-specific (Y chromosome) | Frequently <60 years (early-onset CRC) | Advanced stages (III–IV); linked to metastasis |

| Estrogen Receptor β (ERβ) [63] | Tumor suppressor; maintains epithelial homeostasis | Higher in females | Protective in premenopausal women | Downregulated in CRC; more suppressed in males |

| MLH1 (Methylation) [64] | Mismatch repair gene; silencing leads to microsatellite instability | More common in females >60 | Later onset (>60 years) | Frequently stage II–III in right-sided tumors |

| CDKN2A (p16) Methylation [65] | Tumor suppressor; involved in cell cycle arrest | Slightly higher in males | >50 years | Often in early-stage tumors; associated with serrated pathway |

| APC Mutations [66] | Wnt pathway regulator; initiates adenoma-carcinoma sequence | Present in both sexes | 40–70 years | Early stage (I–II); key in adenoma formation |

| IL-6/CRP [67] | Inflammatory cytokines; reflect tumor-promoting inflammation | Elevated more in males | Often associated with advanced age | Correlates with advanced stage and poor prognosis |

| TILs (Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes) [68] | Reflect host immune response | More abundant in females | Variable | Associated with better outcomes in early to intermediate stages |

4.4. Biomarkers Affected by Lifestyle and Environmental Factors

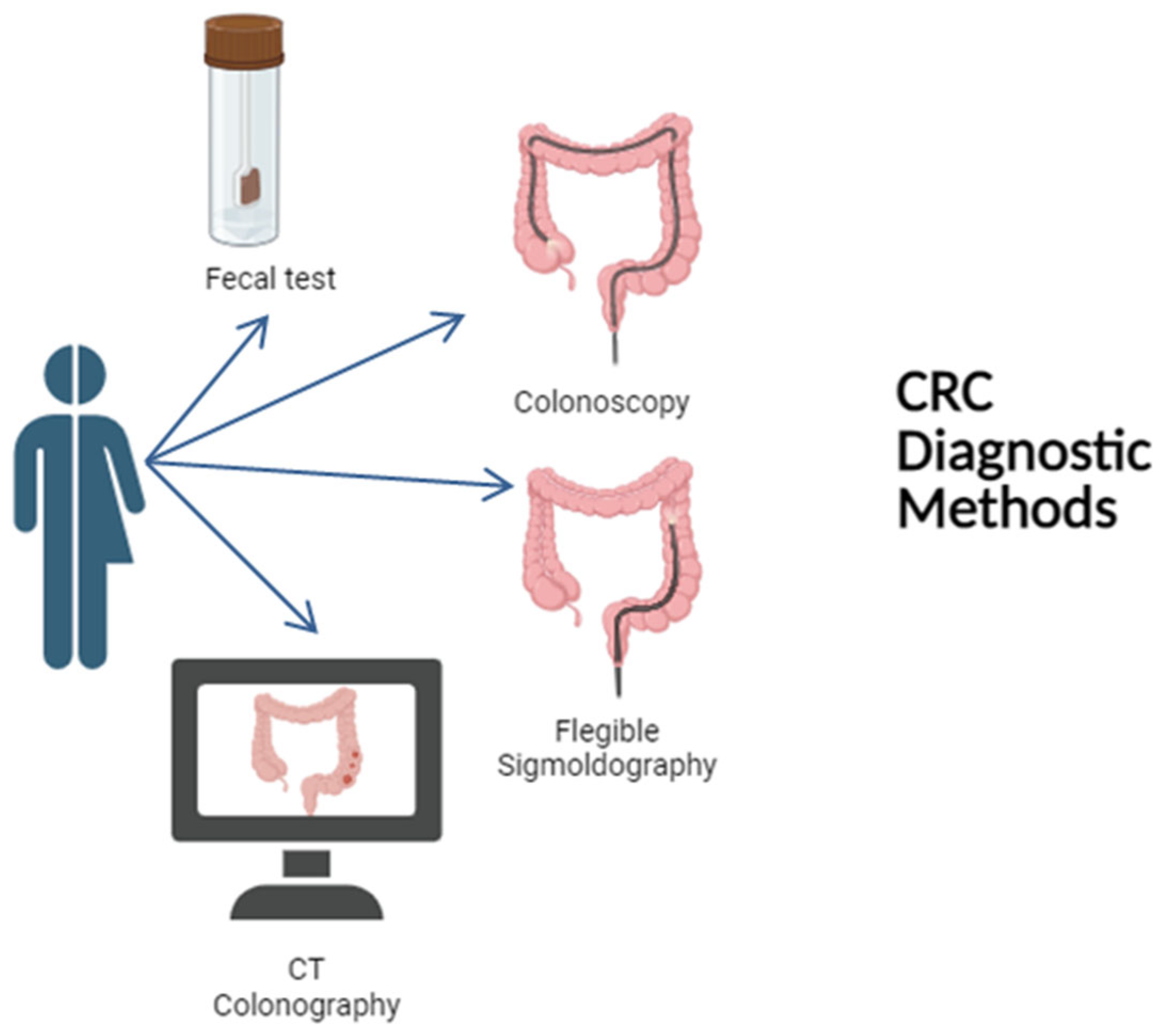

5. CRC Diagnostic Methodologies

5.1. FOBT and FIT

5.2. Colonoscopy

5.3. Flexible Sigmoidoscopy

5.4. CT Colonography

5.5. Stool DNA Tests

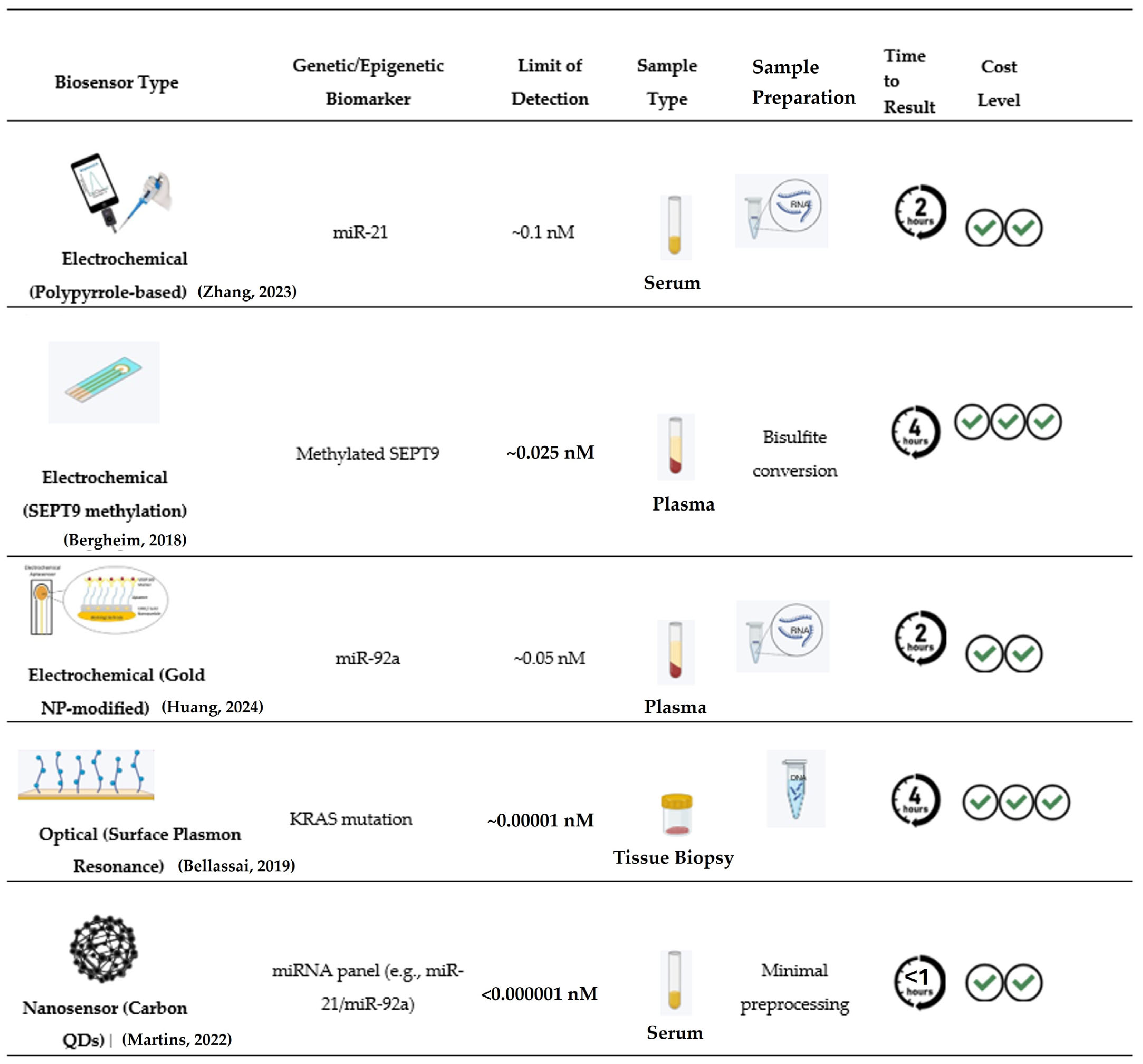

6. Biosensors as Alternatives to Traditional Diagnostic Methods

6.1. Electrochemical Biosensors

6.1.1. Amperometric Biosensors

6.1.2. Potentiometric Biosensors

6.1.3. Impedimetric Biosensors

6.1.4. Novel Multiplexed and Integrated Electrochemical Biosensing Platforms

6.2. Optical Biosensors

6.2.1. Fluorescence-Based Biosensors

6.2.2. Plasmonic and Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Biosensors

6.2.3. Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) Biosensors

6.2.4. Optical Imaging and Endoscopic Biosensing

6.3. Piezoelectric Biosensors

6.4. Electronic (FET-Based) Biosensors

6.5. Nanomaterials for Sensor-Based Applications

6.6. VOC-Based Biosensors

6.7. Microfluidic and Lab-on-a-Chip Biosensors

6.8. Integration with Liquid Biopsy

6.9. Advantages and Limitations of Biosensors in CRC Diagnosis

7. Biosensors in CRC Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM)

7.1. Early Detection of Therapeutic Resistance and Drug Metabolites to Assess Drug Efficacy and Toxicity

7.2. Detection of Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA), Exosomes, or Protein Biomarkers as Indicators of Treatment Response

7.3. Assessment of Targeted Therapy: Drugs That Target Specific Molecular Changes in Cancer Cells

8. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADR | Adenoma Detection Rate |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AJCC | American Joint Committee on Cancer |

| APC | Adenomatous Polyposis Coli |

| AuNPs | Gold Nanoparticles |

| Au@SiO2 | Gold-Coated Silica Nanoparticles |

| BRAF | v-Raf Murine Sarcoma Viral Oncogene Homolog B1 |

| CA | Carbohydrate Antigen |

| CA19-9 | Carbohydrate Antigen 19-9 |

| CEA | Carcinoembryonic Antigen |

| CFU | Colony Forming Unit |

| CLIA | Chemiluminescent Immunoassay |

| CNT | Carbon Nanotube |

| CNTs | Carbon Nanotubes |

| CuO | Copper Oxide |

| CRC | Colorectal Cancer |

| CRISPR | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| ctDNA | Circulating Tumor DNA |

| CTCs | Circulating Tumor Cells |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| DTBP | Dimethyl Dithiobispropionimidate |

| EGFR | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor |

| EIS | Electrolyte–Insulator–Semiconductor |

| EpCAM | Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule |

| ERβ | Estrogen Receptor Beta |

| EV | Extracellular Vesicle |

| FAP | Familial Adenomatous Polyposis |

| FET | Field-Effect Transistor |

| FFF | Field-Flow Fractionation |

| FIT | Fecal Immunochemical Test |

| FITC | Fluorescein Isothiocyanate |

| FOBT | Fecal Occult Blood Test |

| GC | Gas Chromatography |

| GFET | Graphene Field-Effect Transistor |

| GO | Graphene Oxide |

| HER | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Family |

| HER2 | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 |

| HER3 | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 3 |

| HER4 | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 4 |

| HEMT | High Electron Mobility Transistor |

| HNPCC | Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer |

| HRP | Horseradish Peroxidase |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| IDME | Interdigitated Microelectrode |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| ISFET | Ion-Sensitive Field-Effect Transistor |

| KRAS | Kirsten Rat Sarcoma Viral Oncogene Homolog |

| Kd | Dissociation Constant |

| LAMP | Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification |

| LED | Light Emitting Diode |

| LNA | Locked Nucleic Acid |

| LoC | Lab-on-a-Chip |

| LSPR | Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance |

| LSCF | Lanthanum Strontium Cobalt Ferrite |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| MMR | Mismatch Repair |

| MOX | Metal Oxide (Sensor) |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MSI | Microsatellite Instability |

| MSI-H | Microsatellite Instability High |

| MT | Microtubule |

| MXene | Transition Metal Carbide/Nitride (2D Material) |

| NIR | Near-Infrared |

| NK | Natural Killer (Cell) |

| NMOF | Nanoscale Metal–Organic Framework |

| PDMS | Polydimethylsiloxane |

| PEG | Polyethylene Glycol |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| PIK3CA | Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-Bisphosphate 3-Kinase Catalytic Subunit Alpha |

| QCM | Quartz Crystal Microbalance |

| qPCR | Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| RAS | Rat Sarcoma (Oncogene Family) |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| rGO | Reduced Graphene Oxide |

| SCENT B2 | Metal-Oxide Nanosensor Platform (Product Name) |

| SERS | Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering |

| SNP | Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism |

| SPCE | Screen-Printed Carbon Electrode |

| SPR | Surface Plasmon Resonance |

| TDM | Therapeutic Drug Monitoring |

| TGF | Transforming Growth Factor |

| TILs | Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes |

| TNM | Tumor Node Metastasis |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| VOC | Volatile Organic Compound |

| VTSB | Vision-Based Tactile Sensing Balloon |

| ZIF-8 | Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework-8 |

| c-Met | Mesenchymal–Epithelial Transition Factor (Receptor Tyrosine Kinase) |

References

- Weitz, J.; Koch, M.; Debus, J.; Höhler, T.; Galle, P.R.; Büchler, M.W. Colorectal cancer. Lancet 2005, 365, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballinger, A.B.; Anggiansah, C. Colorectal cancer. BMJ 2007, 335, 715–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lech, G.; Słotwiński, R.; Słodkowski, M.; Krasnodębski, I.W. Colorectal cancer tumour markers and biomarkers: Recent therapeutic advances. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 1745–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, M.; Pace, U.; Rega, D.; Costabile, V.; Duraturo, F.; Izzo, P.; Delrio, P. Genetics, diagnosis and management of colorectal cancer (Review). Oncol. Rep. 2015, 34, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait Ouakrim, D.; Pizot, C.; Boniol, M.; Malvezzi, M.; Negri, E.; Bota, M.; Jenkins, M.A.; Bleiberg, H.; Autier, P. Trends in colorectal cancer mortality in Europe: Retrospective analysis of the WHO mortality database. BMJ 2015, 351, h4970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C.E.; Hu, C.Y.; You, Y.N.; Bednarski, B.K.; Rodriguez-Bigas, M.A.; Skibber, J.M.; Cantor, S.B.; Chang, G.J. Increasing disparities in the age-related incidences of colon and rectal cancers in the United States, 1975–2010. JAMA Surg. 2015, 150, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, A.M.D.; Fontham, E.T.H.; Church, T.R.; Flowers, C.R.; Guerra, C.E.; LaMonte, S.J.; Etzioni, R.; McKenna, M.T.; Oeffinger, K.C.; Shih, Y.T.; et al. Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 250–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasi, P.M.; Shahjehan, F.; Cochuyt, J.J.; Li, Z.; Colibaseanu, D.T.; Merchea, A. Rising Proportion of Young Individuals with Rectal and Colon Cancer. Clin. Color. Cancer 2019, 18, e87–e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Fedewa, S.A.; Anderson, W.F.; Miller, K.D.; Ma, J.; Rosenberg, P.S.; Jemal, A. Colorectal Cancer Incidence Patterns in the United States, 1974–2013. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017, 109, djw322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, M.; Sierra, M.S.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut 2017, 66, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Meng, K.; Wang, Y.; Yu, X.; Wang, P.; Zhang, X. The clinical features, management, and survival of elderly patients with colorectal cancer. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2021, 12, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keum, N.; Giovannucci, E. Global burden of colorectal cancer: Emerging trends, risk factors and prevention strategies. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 713–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawla, P.; Sunkara, T.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of colorectal cancer: Incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Prz. Gastroenterol. 2019, 14, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.A.; Lee, J.; Oh, J.H.; Chang, H.J.; Sohn, D.K.; Shin, A.; Kim, J. Genetic Risk Score, Combined Lifestyle Factors and Risk of Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 51, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. Risk factors for advanced colorectal neoplasm in young adults: A meta-analysis. Future Oncol. 2023, 19, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meester, R.G.; Doubeni, C.A.; Lansdorp-Vogelaar, I.; Goede, S.L.; Levin, T.R.; Quinn, V.P.; Ballegooijen, M.; Corley, D.A.; Zauber, A.G. Colorectal cancer deaths attributable to nonuse of screening in the United States. Ann. Epidemiol. 2015, 25, 208–213.e201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henrikson, N.B.; Webber, E.M.; Goddard, K.A.; Scrol, A.; Piper, M.; Williams, M.S.; Zallen, D.T.; Calonge, N.; Ganiats, T.G.; Janssens, A.C.; et al. Family history and the natural history of colorectal cancer: Systematic review. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 702–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoen, R.E.; Razzak, A.; Yu, K.J.; Berndt, S.I.; Firl, K.; Riley, T.L.; Pinsky, P.F. Incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer in individuals with a family history of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2015, 149, 1438–1445.e1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czene, K.; Lichtenstein, P.; Hemminki, K. Environmental and heritable causes of cancer among 9.6 million individuals in the Swedish Family-Cancer Database. Int. J. Cancer 2002, 99, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenstein, P.; Holm, N.V.; Verkasalo, P.K.; Iliadou, A.; Kaprio, J.; Koskenvuo, M.; Pukkala, E.; Skytthe, A.; Hemminki, K. Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer—Analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 343, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, S.; Peters, U.; Berndt, S.; Brenner, H.; Butterbach, K.; Caan, B.J.; Carlson, C.S.; Chan, A.T.; Chang-Claude, J.; Chanock, S.; et al. Estimating the heritability of colorectal cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 3898–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syngal, S.; Brand, R.E.; Church, J.M.; Giardiello, F.M.; Hampel, H.L.; Burt, R.W. ACG clinical guideline: Genetic testing and management of hereditary gastrointestinal cancer syndromes. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 110, 223–262; quiz 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jess, T.; Rungoe, C.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Risk of colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis: A meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 10, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, H.; Chang-Claude, J.; Seiler, C.M.; Rickert, A.; Hoffmeister, M. Protection from colorectal cancer after colonoscopy: A population-based, case-control study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 154, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottet, V.; Jooste, V.; Fournel, I.; Bouvier, A.M.; Faivre, J.; Bonithon-Kopp, C. Long-term risk of colorectal cancer after adenoma removal: A population-based cohort study. Gut 2012, 61, 1180–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, M.S.; Chung, D.C. Application of molecular diagnostics for the detection of Lynch syndrome. Expert. Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2010, 10, 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellcross, C.A.; Bedrosian, S.R.; Daniels, E.; Duquette, D.; Hampel, H.; Jasperson, K.; Joseph, D.A.; Kaye, C.; Lubin, I.; Meyer, L.J.; et al. Implementing screening for Lynch syndrome among patients with newly diagnosed colorectal cancer: Summary of a public health/clinical collaborative meeting. Genet. Med. 2012, 14, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lier, M.G.; Wagner, A.; van Leerdam, M.E.; Biermann, K.; Kuipers, E.J.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Dubbink, H.J.; Dinjens, W.N. A review on the molecular diagnostics of Lynch syndrome: A central role for the pathology laboratory. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2010, 14, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, C.R.; Goel, A. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, 2073–2087.e2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasen, H.F.; Blanco, I.; Aktan-Collan, K.; Gopie, J.P.; Alonso, A.; Aretz, S.; Bernstein, I.; Bertario, L.; Burn, J.; Capella, G.; et al. Revised guidelines for the clinical management of Lynch syndrome (HNPCC): Recommendations by a group of European experts. Gut 2013, 62, 812–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.S.; Lau, R.; Aune, D.; Vieira, R.; Greenwood, D.C.; Kampman, E.; Norat, T. Red and processed meat and colorectal cancer incidence: Meta-analysis of prospective studies. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, B.; Brierley, J.; Byrd, D.; Bosman, F.; Kehoe, S.; Kossary, C.; Piñeros, M.; Van Eycken, E.; Weir, H.K.; Gospodarowicz, M. The TNM classification of malignant tumours-towards common understanding and reasonable expectations. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 849–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.B.; Greene, F.L.; Edge, S.B.; Compton, C.C.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Brookland, R.K.; Meyer, L.; Gress, D.M.; Byrd, D.R.; Winchester, D.P. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiser, M.R. AJCC 8th Edition: Colorectal Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 25, 1454–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zauber, A.G.; Winawer, S.J.; O’Brien, M.J.; Lansdorp-Vogelaar, I.; van Ballegooijen, M.; Hankey, B.F.; Shi, W.; Bond, J.H.; Schapiro, M.; Panish, J.F.; et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, M.; Ravula, S.; Tatishchev, S.F.; Wang, H.L. Colorectal carcinoma: Pathologic aspects. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2012, 3, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, J.; Atlas, S.; Enno, A.; Santos, L.; Humphries, J.; Kirwan, A. Giant villous adenoma of the sigmoid colon: An unusual cause of homogeneous, segmental bowel wall thickening. BJR Case Rep. 2020, 6, 20200016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelstein, B.; Papadopoulos, N.; Velculescu, V.E.; Zhou, S.; Diaz, L.A.; Kinzler, K.W. Cancer genome landscapes. Science 2013, 339, 1546–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fearon, E.R. Molecular genetics of colorectal cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2011, 6, 479–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dienstmann, R.; Vermeulen, L.; Guinney, J.; Kopetz, S.; Tejpar, S.; Tabernero, J. Consensus molecular subtypes and the evolution of precision medicine in colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, H.T.; de la Chapelle, A. Hereditary colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 919–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, I.A.; Lewis, P.D.; Mattos, C. A comprehensive survey of Ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 2457–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lan, Z.; Liao, W.; Horner, J.W.; Xu, X.; Liu, J.; Yoshihama, Y.; Jiang, S.; Shim, H.S.; Slotnik, M.; et al. Histone demethylase KDM5D upregulation drives sex differences in colon cancer. Nature 2023, 619, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zheng, C.; You, F.; Wang, M.; Xiao, C.; Li, X. Sex differences in colorectal cancer: With a focus on sex hormone-gut microbiome axis. Cell Commun. Signal 2024, 22, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhan, K.; Liu, K. Epigenetics and colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Cancers 2013, 5, 676–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spolverato, G.; Fassan, M.; Capelli, G.; Scarpa, M.; Negro, S.; Chiminazzo, V.; Kotsafti, A.; Angriman, I.; Campi, M.; De Simoni, O.; et al. IMMUNOREACT 5: Female patients with rectal cancer have better immune editing mechanisms than male patients—A cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 2023, 109, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Flores, E.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Élez, E.; Redondo-Cerezo, E.; Safont, M.J.; Vera García, R. Gender and sex differences in colorectal cancer screening, diagnosis and treatment. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2025, 27, 2825–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetzler, K.L.; Hardee, J.P.; Puppa, M.J.; Narsale, A.A.; Sato, S.; Davis, J.M.; Carson, J.A. Sex differences in the relationship of IL-6 signaling to cancer cachexia progression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1852, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Hua, X.; Labadie, J.D.; Harrison, T.A.; Dai, J.Y.; Lindstrom, S.; Lin, Y.; Berndt, S.I.; Buchanan, D.D.; Campbell, P.T.; et al. Genetic variants associated with circulating C-reactive protein levels and colorectal cancer survival: Sex-specific and lifestyle factors specific associations. Int. J. Cancer 2022, 150, 1447–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimptsch, K.; Aleksandrova, K.; Fedirko, V.; Jenab, M.; Gunter, M.J.; Siersema, P.D.; Wu, K.; Katzke, V.; Kaaks, R.; Panico, S.; et al. Pre-diagnostic C-reactive protein concentrations, CRP genetic variation and mortality among individuals with colorectal cancer in Western European populations. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wankhede, D.; Yuan, T.; Kloor, M.; Halama, N.; Brenner, H.; Hoffmeister, M. Clinical significance of combined tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and microsatellite instability status in colorectal cancer: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 9, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yager, S.S.; Chen, L.; Cheung, W.Y. Sex-based disparities in colorectal cancer screening. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 37, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Geng, S.; Luo, H.; Wang, W.; Mo, Y.-Q.; Luo, Q.; Wang, L.; Song, G.-B.; Sheng, J.-P.; Xu, B. Signaling pathways involved in colorectal cancer: Pathogenesis and targeted therapy. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2024, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzwieser, M.; Entfellner, E.; Werner, B.; Pulverer, W.; Pfeiler, G.; Hacker, S.; Cichna-Markl, M. Hypermethylation of CDKN2A exon 2 in tumor, tumor-adjacent and tumor-distant tissues from breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisenberger, D.J.; Siegmund, K.D.; Campan, M.; Young, J.; Long, T.I.; Faasse, M.A.; Kang, G.H.; Widschwendter, M.; Weener, D.; Buchanan, D.; et al. CpG island methylator phenotype underlies sporadic microsatellite instability and is tightly associated with BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vogel, S.; Weijenberg, M.P.; Herman, J.G.; Wouters, K.A.; de Goeij, A.F.; van den Brandt, P.A.; de Bruïne, A.P.; van Engeland, M. MGMT and MLH1 promoter methylation versus APC, KRAS and BRAF gene mutations in colorectal cancer: Indications for distinct pathways and sequence of events. Ann. Oncol. 2009, 20, 1216–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppedè, F.; Migheli, F.; Lopomo, A.; Failli, A.; Legitimo, A.; Consolini, R.; Fontanini, G.; Sensi, E.; Servadio, A.; Seccia, M.; et al. Gene promoter methylation in colorectal cancer and healthy adjacent mucosa specimens: Correlation with physiological and pathological characteristics, and with biomarkers of one-carbon metabolism. Epigenetics 2014, 9, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccon, C.; Borga, C.; Angerilli, V.; Bergamo, F.; Munari, G.; Sabbadin, M.; Gasparello, J.; Schiavi, F.; Zovato, S.; Scarpa, M.; et al. MLH1 gene promoter methylation status partially overlaps with CpG methylator phenotype (CIMP) in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2025, 266, 155786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Huang, G.; Cong, Y.; Yu, Y.; Li, Y. Sex-related Differences in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: The Potential Role of Sex Hormones. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2022, 28, 1766–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, N.; Loh, K.P.; Liposits, G.; Arora, S.P.; Vertino, P.; Janelsins, M. Epigenetic and inflammatory markers in older adults with cancer: A Young International Society of Geriatric Oncology narrative review. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2024, 15, 101655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refaat, B.; Aslam, A.; Idris, S.; Almalki, A.H.; Alkhaldi, M.Y.; Asiri, H.A.; Almaimani, R.A.; Mujalli, A.; Minshawi, F.; Alamri, S.A.; et al. Profiling estrogen, progesterone, and androgen receptors in colorectal cancer in relation to gender, menopausal status, clinical stage, and tumour sidedness. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1187259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deycmar, S.; Johnson, B.J.; Ray, K.; Schaaf, G.W.; Ryan, D.P.; Cullin, C.; Dozier, B.L.; Ferguson, B.; Bimber, B.N.; Olson, J.D.; et al. Epigenetic MLH1 silencing concurs with mismatch repair deficiency in sporadic, naturally occurring colorectal cancer in rhesus macaques. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Cai, W.; Shi, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Jiao, J.; Chen, M. The prognostic value of CDKN2A hypermethylation in colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 108, 2542–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Ying, J.; Zang, J.; Lu, H.; Zhao, X.; Yang, P.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Gong, Z.; Zhang, D.; et al. Specific Mutations in APC, with Prognostic Implications in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Res. Treat. 2023, 55, 1270–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajka-Francuz, P.; Cisoń-Jurek, S.; Czajka, A.; Kozaczka, M.; Wojnar, J.; Chudek, J.; Francuz, T. Systemic Interleukins’ Profile in Early and Advanced Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 23, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, A.T.; Saqi, I.K.; Justesen, T.F.; Madsen, M.T.; Gögenur, I.; Orhan, A. The prognostic impact of tumor mutations and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with localized pMMR colorectal cancer—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2025, 211, 104714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veettil, S.K.; Wong, T.Y.; Loo, Y.S.; Playdon, M.C.; Lai, N.M.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Chaiyakunapruk, N. Role of Diet in Colorectal Cancer Incidence: Umbrella Review of Meta-analyses of Prospective Observational Studies. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2037341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanella, G.; Archibugi, L.; Stigliano, S.; Capurso, G. Alcohol and gastrointestinal cancers. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2019, 35, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, H.J.; Lee, H.S.; Jang, B.I.; Kim, D.B.; Kim, J.H.; Park, J.J.; Kim, H.G.; Baek, I.H.; Lee, J.; Kim, B. Sex-specific differences in colorectal cancer: A multicenter retrospective cohort study. Cancer Rep. 2023, 6, e1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, W.; Jung, S.Y.; Jang, Y.; Lee, K. Lifestyle factors and colorectal cancer prediction: A nomogram-based model. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, E.; Tanis, P.J.; Vleugels, J.L.A.; Kasi, P.M.; Wallace, M.B. Colorectal cancer. Lancet 2019, 394, 1467–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.S.; Piper, M.A.; Perdue, L.A.; Rutter, C.; Webber, E.M.; O’Connor, E.; Smith, N.; Whitlock, E.P. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force; NBK373584; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2016.

- Rex, D.K.; Boland, C.R.; Dominitz, J.A.; Giardiello, F.M.; Johnson, D.A.; Kaltenbach, T.; Levin, T.R.; Lieberman, D.; Robertson, D.J. Colorectal Cancer Screening: Recommendations for Physicians and Patients from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 112, 1016–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.A.; Barkun, A.N.; Cohen, L.B.; Dominitz, J.A.; Kaltenbach, T.; Martel, M.; Robertson, D.J.; Boland, C.R.; Giardello, F.M.; Lieberman, D.A.; et al. Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: Recommendations from the U.S. multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2014, 80, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutter, M.D.; Beintaris, I.; Valori, R.; Chiu, H.M.; Corley, D.A.; Cuatrecasas, M.; Dekker, E.; Forsberg, A.; Gore-Booth, J.; Haug, U.; et al. World Endoscopy Organization Consensus Statements on Post-Colonoscopy and Post-Imaging Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 909–925.e903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkin, W.; Wooldrage, K.; Parkin, D.M.; Kralj-Hans, I.; MacRae, E.; Shah, U.; Duffy, S.; Cross, A.J. Long term effects of once-only flexible sigmoidoscopy screening after 17 years of follow-up: The UK Flexible Sigmoidoscopy Screening randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 1299–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickhardt, P.J.; Kim, D.H. Colorectal cancer screening with CT colonography: Key concepts regarding polyp prevalence, size, histology, morphology, and natural history. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2009, 193, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golfinopoulou, R.; Hatziagapiou, K.; Mavrikou, S.; Kintzios, S. Unveiling Colorectal Cancer Biomarkers: Harnessing Biosensor Technology for Volatile Organic Compound Detection. Sensors 2024, 24, 4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Orazio, P. Biosensors in clinical chemistry. Clin. Chim. Acta 2003, 334, 41–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.P. Biosensors: Sense and sensibility. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 3184–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieshaber, D.; MacKenzie, R.; Vörös, J.; Reimhult, E. Electrochemical Biosensor—Sensor Principles and Architectures. Sensors 2008, 8, 1400–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Aamri, M.; Yammouri, G.; Mohammadi, H.; Amine, A.; Korri-Youssoufi, H. Electrochemical Biosensors for Detection of MicroRNA as a Cancer Biomarker: Pros and Cons. Biosensors 2020, 10, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tan, X.; Wang, P.; Qin, J. Application of Polypyrrole-Based Electrochemical Biosensor for the Early Diagnosis of Colorectal Cancer. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrero-Martín, A.; Santiago, S.; Serafín, V.; Montero-Calle, A.; Pingarrón, J.M.; Barderas, R.; Campuzano, S. Gold-silica hybrid nanolabels decorated with recognition and signaling bioreagents for enhanced electrochemical immunodetection of chemokine ligand-12 in colorectal cancer early diagnosis and monitoring. Mikrochim. Acta 2025, 192, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Povedano, E.; Ruiz-Valdepeñas Montiel, V.; Sebuyoya, R.; Torrente-Rodríguez, R.M.; Garranzo-Asensio, M.; Montero-Calle, A.; Pingarrón, J.M.; Barderas, R.; Bartosik, M.; Campuzano, S. Bringing to Light the Importance of the miRNA Methylome in Colorectal Cancer Prognosis Through Electrochemical Bioplatforms. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 4580–4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xiao, G.; Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Hu, Q.; Wu, J.; Song, M.; Qiao, J.; Xu, C. Electrochemical biosensors for measurement of colorectal cancer biomarkers. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2021, 413, 2407–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Jin, L.; Wang, F. Applications and development trend of biosensors in the detection and diagnosis of gastrointestinal tumors. BioMed. Eng. OnLine 2025, 24, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikaeeli Kangarshahi, B.; Naghib, S.M.; Rabiee, N. DNA/RNA-based electrochemical nanobiosensors for early detection of cancers. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2024, 61, 473–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girigoswami, K.; Girigoswami, A. A Review on the Role of Nanosensors in Detecting Cellular miRNA Expression in Colorectal Cancer. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2021, 21, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Zhang, J.Q.; Li, L.; Guo, M.M.; He, Y.F.; Dong, Y.M.; Meng, H.; Yi, F. Advanced Glycation End Products in the Skin: Molecular Mechanisms, Methods of Measurement, and Inhibitory Pathways. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 837222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štukovnik, Z.; Bren, U. Recent Developments in Electrochemical-Impedimetric Biosensors for Virus Detection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, R.; Morales-Lozada, Y.; Sánchez Colón, B.J.; Hernandez, A.R.; Roy, S.; Cabrera, C.R. Colorectal Cancer Label-Free Impedimetric Immunosensor for Blood-Based Biomarker CCSP-2. ACS Meas. Sci. Au 2025, 5, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, P.; Cha, B.S.; Kim, S.; Lee, E.S.; Yoon, T.; Woo, J.; Park, K.S. T7 Endonuclease I-mediated voltammetric detection of KRAS mutation coupled with horseradish peroxidase for signal amplification. Mikrochim. Acta 2022, 189, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tertis, M.; Leva, P.I.; Bogdan, D.; Suciu, M.; Graur, F.; Cristea, C. Impedimetric aptasensor for the label-free and selective detection of Interleukin-6 for colorectal cancer screening. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 137, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.B.C.; Reut, J.; Rappich, J.; Hinrichs, K.; Syritski, V. Molecularly Imprinted Polymer-Based Electrochemical Sensor for the Detection of Azoxystrobin in Aqueous Media. Polymers 2024, 16, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejerina-Miranda, S.; Blázquez-García, M.; Serafín, V.; Montero-Calle, A.; Garranzo-Asensio, M.; Reviejo, A.J.; Pedrero, M.; Pingarrón, J.M.; Barderas, R.; Campuzano, S. Electrochemical biotool for the dual determination of epithelial mucins associated to prognosis and minimal residual disease in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 248, 125996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Povedano, E.; Pérez-Ginés, V.; Torrente-Rodríguez, R.M.; Rejas-González, R.; Montero-Calle, A.; Peláez-García, A.; Feliú, J.; Pedrero, M.; Pingarrón, J.M.; Barderas, R.; et al. Tracking Globally 5-Methylcytosine and Its Oxidized Derivatives in Colorectal Cancer Epigenome Using Bioelectroanalytical Technologies. ACS Sens. 2025, 10, 2049–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Nie, Y.; Liang, Z.; Peilin, W.; Ma, Q. Ag3PO4 NP@MoS2 nanosheet enhanced F, S-doped BN quantum dot electrochemiluminescence biosensor for K-ras tumor gene detection. Talanta 2021, 228, 122221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astolfi, M.; Zonta, G.; Malagù, C.; Anania, G.; Rispoli, G. MOX Nanosensors to Detect Colorectal Cancer Relapses from Patient’s Blood at Three Years Follow-Up, and Gender Correlation. Biosensors 2025, 15, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naresh, V.; Lee, N. A Review on Biosensors and Recent Development of Nanostructured Materials-Enabled Biosensors. Sensors 2021, 21, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, J. Optical biosensors: An exhaustive and comprehensive review. Analyst 2020, 145, 1605–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; White, I.M.; Shopova, S.I.; Zhu, H.; Suter, J.D.; Sun, Y. Sensitive optical biosensors for unlabeled targets: A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2008, 620, 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, B.; Kumar, S.; Kaushik, B.K. Recent advancements in optical biosensors for cancer detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 197, 13805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Si, Y.; Lee, H.J. Electrochemical and Optical Biosensors for Colorectal Cancer Protein Biomarkers: A Review. Appl. Chem. Eng. 2021, 32, 253–259. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Han, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, M.; Liu, P.; Li, G. Sensor Array Fabricated with Nanoscale Metal-Organic Frameworks for the Histopathological Examination of Colon Cancer. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 10772–10778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadzadeh-Raji, M.; Ghafar-Zadeh, E.; Amoabediny, G. An Optically-Transparent Aptamer-Based Detection System for Colon Cancer Applications Using Gold Nanoparticles Electrodeposited on Indium Tin Oxide. Sensors 2016, 16, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuddin, S.H.; Jayne, D.G.; Tomlinson, D.C.; McPherson, M.J.; Millner, P.A. Selection and characterisation of Affimers specific for CEA recognition. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avram, L.; Stefancu, A.; Crisan, D.; Leopold, N.; Donca, V.; Buzdugan, E.; Craciun, R.; Andras, D.; Coman, I. Recent advances in surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy based liquid biopsy for colorectal cancer (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, R.; Mulana, F.; Cavallotti, C.; Tortora, G.; Vigliar, M.; Vatteroni, M.; Menciassi, A. An Innovative Wireless Endoscopic Capsule with Spherical Shape. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2017, 11, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerald, A.; Na Ayuddhaya, K.P.; McCandless, M.; Hsu, P.; Pang, J.; Mankad, A.; Chu, A.; Aihara, H.; Russo, S. Ex Vivo Evaluation of a Soft Optical Blood Sensor for Colonoscopy. Device 2024, 2, 100422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorthy, D.N.; Dhinasekaran, D.; Rebecca, P.N.B.; Rajendran, A.R. Optical Biosensors for Detection of Cancer Biomarkers: Current and Future Perspectives. J. Biophotonics 2024, 17, e202400243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, J.; Fan, S.; Ding, S.; Ren, L. Gold Nanoparticles Based Optical Biosensors for Cancer Biomarker Proteins: A Review of the Current Practices. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 877193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azab, M.Y.; Hameed, M.F.O.; Obayya, S.S.A. Overview of Optical Biosensors for Early Cancer Detection: Fundamentals, Applications and Future Perspectives. Biology 2023, 12, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, H.-Y.; Jia, Z.-R.; Qiao, P.-P.; Pi, X.-T.; Chen, J.; Deng, L.-H. Advances in the Early Detection of Lung Cancer using Analysis of Volatile Organic Compounds: From Imaging to Sensors. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP 2014, 15, 4377–4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascini, M.; Tombelli, S. Biosensors for biomarkers in medical diagnostics. Biomarkers 2008, 13, 637–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenet, A.; Mahadevan, E.; Elangovan, S.; Yan, J.; Siddiq, K.; Liu, S.; Ladwa, A.; Narayanan, R.; Dakkak, J.; Benassi, T.; et al. Flexible piezoelectric sensor for real-time image-guided colonoscopies: A solution to endoscopic looping challenges in clinic. In Proceedings of the SPIE, Medical Imaging 2020: Image-Guided Procedures, Robotic Interventions, and Modeling, Huston, TX, USA, 16 March 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, O.C.; Kim, H.; Xue, J.; Mohanraj, T.G.; Hirata, Y.; Ikoma, N.; Alambeigi, F. Design and Development of a Novel Soft and Inflatable Tactile Sensing Balloon for Early Diagnosis of Colorectal Cancer Polyps. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.09651v1. Erratum in IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 26564–26573. https://doi.org/10.1109/jsen.2024.3423773. PMID: 37791107; PMCID: PMC10543017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, L.; Xu, C.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Tang, D.; Xue, F. amplified QCM immunoassay for carcinoembryonic antigen with colorectal cancer using horseradish peroxidase nanospheres and enzymatic biocatalytic precipitation. Analyst 2020, 145, 6111–6118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandas, P.J.; Luo, J.; Quan, A.; Li, C.; Fu, C.; Fu, Y.Q. Graphene oxide-Au nano particle coated quartz crystal microbalance biosensor for the real time analysis of carcinoembryonic antigen. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 4118–4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Zheng, S.R.; Fan, J.; Cai, S.L.; Dai, Z.; Zou, X.Y.; Teng, S.H.; Zhang, W.G. A new QCM signal enhancement strategy based on streptavidin@metal-organic framework complex for miRNA detection. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1095, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayleigh, L. On Waves Propagated along the Plane Surface of an Elastic Solid. Proc. Lond. Math. Soc. 1885, 1, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Wu, W.; Yang, P.; Luo, J.; Fu, C.; Han, J.-C.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Y. A review of surface acoustic wave sensors: Mechanisms, stability and future prospects. Sens. Rev. 2024, 44, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergheim, J.; Semaan, A.; Gevensleben, H.; Groening, S.; Knoblich, A.; Dietrich, J.; Weber, J.; Kalff, J.C.; Bootz, F.; Kristiansen, G.; et al. Potential of quantitative SEPT9 and SHOX2 methylation in plasmatic circulating cell-free DNA as auxiliary staging parameter in colorectal cancer: A prospective observational cohort study. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 118, 1217–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, D.; Banerjee, S. Surface Acoustic Wave (SAW) Sensors: Physics, Materials, and Applications. Sensors 2022, 22, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallil, H.; Omar-Aouled, N.; Plano, B.; Delépée, R.; Agrofoglio, L.A.; Dejous, C.; Rebière, D. Love Wave Sensor Based on Thin Film Molecularly Imprinted Polymer: Study of VOCs Adsorption. J. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2014, 9, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, S.; Bhethanabotla, V.R. Integrating Metal-Enhanced Fluorescence and Surface Acoustic Waves for Sensitive and Rapid Quantification of Cancer Biomarkers from Real Matrices. ACS Sens. 2018, 3, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poghossian, A.; Schöning, M.J. Capacitive Field-Effect EIS Chemical Sensors and Biosensors: A Status Report. Sensors 2020, 20, 5639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulikkathodi, A.K.; Sarangadharan, I.; Chen, Y.H.; Lee, G.Y.; Chyi, J.I.; Lee, G.B.; Wang, Y.L. Dynamic monitoring of transmembrane potential changes: A study of ion channels using an electrical double layer-gated FET biosensor. Lab. Chip 2018, 18, 1047–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeun, M.; Lee, H.J.; Park, S.; Do, E.J.; Choi, J.; Sung, Y.N.; Hong, S.M.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, D.H.; Kang, J.Y.; et al. A Novel Blood-Based Colorectal Cancer Diagnostic Technology Using Electrical Detection of Colon Cancer Secreted Protein-2. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1802115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, T.-M.; Liao, P.-Y. High sensitivity and rapid detection of KRAS and BRAF gene mutations in colorectal cancer using YbTixOy electrolyte-insulator-semiconductor biosensors. Mater. Today Chem. 2022, 25, 100979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, P.; Kaur, G.; Singh, N.K. Nanotechnology for colorectal cancer detection and treatment. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 6497–6511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, F.; Khan, M.H.; Jilani, S.; Jafry, A.T.; Yaqub, A.; Ajab, H. Revolutionary Advances in Nanomaterial-Based Electrochemical Biosensors for Precise Cancer Biomarker Analysis. Talanta Open 2025, 12, 100509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, C.; Rouhi, J. A biosensor based on graphene oxide nanocomposite for determination of carcinoembryonic antigen in colorectal cancer biomarker. Environ. Res. 2023, 238, 117113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, Z.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, Z.; Mo, G.; Xia, Y.; et al. A Gold Nanoparticles and MXene Nanocomposite Based Electrochemical Sensor for Point-of-Care Monitoring of Serum Biomarkers. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 16980–16994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergengren, O.; Pekala, K.R.; Matsoukas, K.; Fainberg, J.; Mungovan, S.F.; Bratt, O.; Bray, F.; Brawley, O.; Luckenbaugh, A.N.; Mucci, L.; et al. 2022 Update on Prostate Cancer Epidemiology and Risk Factors—A Systematic Review. Eur. Urol. 2023, 84, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, W.; Wan, S.; Qu, B.; Liao, F.; Cheng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, Z.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, Q. Spatially Selective MicroRNA Imaging in Human Colorectal Cancer Tissues Using a Multivariate-Gated Signal Amplification Nanosensor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 6679–6687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, F.; Yun, B.; Ming, J.; Yu, T.; Li, B.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, Z.H.; Song, C.; Zhao, M.; et al. Non-Invasive Diagnosis of Early Colorectal Cancerization via Amplified Sensing of MicroRNA-21 in NIR-II Window. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2501378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Zheng, J.; Bu, J.; Li, R.; Li, X.; Fan, S.; Ling, K.; Jiang, H. Mn2+-modified black phosphorus nanosensor for detection of exosomal microRNAs and exosomes. Microchim. Acta 2023, 190, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishwar, D.; Venkatakrishnan, K.; Tan, B.; Haldavnekar, R. DNA Methylation Signatures of Tumor-Associated Natural Killer Cells with Self-Functionalized Nanosensor Enable Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis. Nano Lett. 2023, 23, 4142–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, B.; Zhou, J.; Li, Z.; Song, J.; An, P.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Lan, F.; Ying, B.; Wu, Y. Ultrasensitive DNA Methylation Ratio Detection Based on the Target-Induced Nanoparticle-Coupling and Site-Specific Base Oxidation Damage for Colorectal Cancer. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 6261–6270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadian-Ghazvini, S.; Dashtestani, F.; Hakimian, F.; Ghourchian, H. An electrochemical genosensor for differentiation of fully methylated from fully unmethylated states of BMP3 gene. Bioelectrochemistry 2021, 142, 107924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, B.A.; Mac, Q.D.; Kwong, G.A. Nanosensors to Detect Protease Activity In Vivo for Noninvasive Diagnostics. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 307, 57937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heest, A.E.; Deng, F.; Zhao, R.T.; Harzallah, N.S.; Fleming, H.E.; Bhatia, S.N.; Hao, L. CRISPR-Cas-mediated Multianalyte Synthetic Urine Biomarker Test for Portable Diagnostics. J. Vis. Exp. 2023, 202, e66189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Rohani, N.; Zhao, R.T.; Pulver, E.M.; Mak, H.; Kelada, O.J.; Ko, H.; Fleming, H.E.; Gertler, F.B.; Bhatia, S.N. Microenvironment-triggered multimodal precision diagnostics. Nat. Mater. 2021, 20, 1440–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Zhang, P.; Chen, H.; Zhou, B.; Qin, Y.; Fan, T.; Sun, Q.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y. Au@Fe3O4 Nanoparticle-Based Colorimetric Aptasensor for Noninvasive Screening of Colorectal Cancer via Detection of Parvimonas micra. ACS Sens. 2025, 10, 1053–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, D.; Han, S.; Zhang, H.; He, Y.; Li, Y. Predictive biomarkers of colorectal cancer. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2019, 83, 107106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poļaka, I.; Mežmale, L.; Anarkulova, L.; Kononova, E.; Vilkoite, I.; Veliks, V.; Ļeščinska, A.M.; Stonāns, I.; Pčolkins, A.; Tolmanis, I.; et al. The Detection of Colorectal Cancer through Machine Learning-Based Breath Sensor Analysis. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Bae, H.; Pal, Y.; Panigrahi, P.; Nazir, S.; Naher, M.; Assen, A.; Lee, H. Atomistic Insights into Detection of Volatile Organic Compounds Using Transition Metal Dichalcogenides-Based Nanosensors. Langmuir 2025, 41, 13134–13143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astolfi, M.; Rispoli, G.; Anania, G.; Zonta, G.; Malagù, C. Chemoresistive Nanosensors Employed to Detect Blood Tumor Markers in Patients Affected by Colorectal Cancer in a One-Year Follow Up. Cancers 2023, 15, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, H.; Daulton, E.; Bannaga, A.S.; Arasaradnam, R.P.; Covington, J.A. Non-Invasive Detection and Staging of Colorectal Cancer Using a Portable Electronic Nose. Sensors 2021, 21, 5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasaradnam, R.P.; Krishnamoorthy, A.; Hull, M.A.; Wheatstone, P.; Kvasnik, F.; Persaud, K.C. The Development and Optimisation of a Urinary Volatile Organic Compound Analytical Platform Using Gas Sensor Arrays for the Detection of Colorectal Cancer. Sensors 2025, 25, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, C.M.D.; Gómez, J.K.C.; Bautista Gómez, G.A.; Carrero Carrero, J.L.; Ramírez, R.F. Colorectal Cancer Detection Through Sweat Volatilome Using an Electronic Nose System and GC-MS Analysis. Cancers 2025, 17, 2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armakolas, A.; Kotsari, M.; Koskinas, J. Liquid Biopsies, Novel Approaches and Future Directions. Cancers 2023, 15, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghjooy Javanmard, S.; Rafiee, L.; Bahri Najafi, M.; Khorsandi, D.; Hasan, A.; Vaseghi, G.; Makvandi, P. Microfluidic-based technologies in cancer liquid biopsy: Unveiling the role of horizontal gene transfer (HGT) materials. Environ. Res. 2023, 238, 117083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yapeter, C.A.; Mantikas, K.-T.; Gulli, C.; Moser, N.; Simillis, C.; Melpomeni, K. Electrochemical Sensing of the Colorectal Cancer BRAF p.V600E Mutation Using a Lab-on-Chip Integrated DNA Amplification Analysis Method. In Proceedings of the IEEE SENSORS, Kobe, Japan, 20–23 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Fang, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Teng, F.; Li, C. Nanozyme-Based Pump-free Microfluidic Chip for Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis via Circulating Cancer Stem Cell Detection. ACS Sens. 2024, 9, 5090–5098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, W.; Duan, H.; Xiao, F. Bimetal-organic framework-integrated electrochemical sensor for on-chip detection of H. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2024, 260, 116463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, C.E.; Koo, B.; Lee, T.Y.; Han, K.; Lim, S.B.; Park, I.J.; Shin, Y. Simple and Low-Cost Sampling of Cell-Free Nucleic Acids from Blood Plasma for Rapid and Sensitive Detection of Circulating Tumor DNA. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1800614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Liu, S.; Jiang, J.; Shen, G.; Yu, R. A sensitive electrochemical biosensor for detection of DNA methyltransferase activity by combining DNA methylation-sensitive cleavage and terminal transferase-mediated extension. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 6280–6282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, Y.; Kosaka, N.; Konishi, Y.; Ohta, H.; Okamoto, H.; Sonoda, H.; Nonaka, R.; Yamamoto, H.; Ishii, H.; Mori, M.; et al. Ultra-sensitive liquid biopsy of circulating extracellular vesicles using ExoScreen. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marassi, V.; Giordani, S.; Placci, A.; Punzo, A.; Caliceti, C.; Zattoni, A.; Reschiglian, P.; Roda, B.; Roda, A. Emerging Microfluidic Tools for Simultaneous Exosomes and Cargo Biosensing in Liquid Biopsy: New Integrated Miniaturized FFF-Assisted Approach for Colon Cancer Diagnosis. Sensors 2023, 23, 9432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temperini, M.E.; Di Giacinto, F.; Romanò, S.; Di Santo, R.; Augello, A.; Polito, R.; Baldassarre, L.; Giliberti, V.; Papi, M.; Basile, U.; et al. Antenna-enhanced mid-infrared detection of extracellular vesicles derived from human cancer cell cultures. J. Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyano, A.; Serrano-Pertierra, E.; Duque, J.M.; Ramos, V.; Teruel-Barandiarán, E.; Fernández-Sánchez, M.T.; Salvador, M.; Martínez-García, J.C.; Sánchez, L.; García-Flórez, L.; et al. Magnetic Lateral Flow Immunoassay for Small Extracellular Vesicles Quantification: Application to Colorectal Cancer Biomarker Detection. Sensors 2021, 21, 3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haldavnekar, R.; Venkatakrishnan, K.; Tan, B. Cancer Stem Cell Derived Extracellular Vesicles with Self-Functionalized 3D Nanosensor for Real-Time Cancer Diagnosis: Eliminating the Roadblocks in Liquid Biopsy. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 12226–12243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Gopalan, V.; Lam, A.K.; Shiddiky, M.J.A. Current advances in detecting genetic and epigenetic biomarkers of colorectal cancer. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 239, 115611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, P.-T.; Chen, Y.-L.; Lin, Y.-H.; Wang, C.-C.; Chang, H.-T. Functional gold nanoparticles for analysis and delivery of nucleic acids. J. Food Drug Anal. 2024, 32, 252–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellassai, N.; D’AGata, R.; Jungbluth, V.; Spoto, G. Surface Plasmon Resonance for Biomarker Detection: Advances in Non-invasive Cancer Diagnosis. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.S.M.; LaGrow, A.P.; Prior, J.A.V. Quantum Dots for Cancer-Related miRNA Monitoring. ACS Sens. 2022, 7, 1269–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominitz, J.A. Beyond the Scope: The Promise and Limitations of Blood-Based Colorectal Cancer Screening. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 21, 397–399. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Shen, X.; Chen, G.; Du, J. Drug Resistance in Colorectal Cancer: From Mechanism to Clinic. Cancers 2022, 14, 2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.N.; Tian, Q.; Teng, Q.X.; Wurpel, J.N.D.; Zeng, L.; Pan, Y.; Chen, Z.S. Understanding and targeting resistance mechanisms in cancer. MedComm 2023, 4, e265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salame, N.; Fooks, K.; El-Hachem, N.; Bikorimana, J.P.; Mercier, F.E.; Rafei, M. Recent Advances in Cancer Drug Discovery Through the Use of Phenotypic Reporter Systems, Connectivity Mapping, and Pooled CRISPR Screening. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 852143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgour, E.; Rothwell, D.G.; Brady, G.; Dive, C. Liquid Biopsy-Based Biomarkers of Treatment Response and Resistance. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemdan, M.; Ali, M.A.; Doghish, A.S.; Mageed, S.S.A.; Elazab, I.M.; Khalil, M.M.; Mabrouk, M.; Das, D.B.; Amin, A.S. Innovations in Biosensor Technologies for Healthcare Diagnostics and Therapeutic Drug Monitoring: Applications, Recent Progress, and Future Research Challenges. Sensors 2024, 24, 5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón, V.; Pinacho, D.G.; Bustos, R.H.; Garzón, G.; Bustamante, S. Optical Biosensors for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. Biosensors 2019, 9, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Pan, P.; Huang, H.; Liu, H. Cr-MOF-Based Electrochemical Sensor for the Detection of P-Nitrophenol. Biosensors 2022, 12, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.N.; Lin, Y.L.; Chiou, Y.E.; Leung, W.H.; Weng, W.H. Urinary MicroRNA Sensing Using Electrochemical Biosensor to Evaluate Colorectal Cancer Progression. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, R.; Lakshmipriya, T.; Gopinath, S.C.; Ismail, I.; Subramaniam, S.; Chen, Y. La0.6Sr0.4Co0.2Fe0.8O3-∝ (LSCF) biosensor for diagnosing colorectal cancer: A quaternary alloy on an interdigitated electrode. Arab. J. Chemistry 2025, 18, 1232024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, L.A.; Bardelli, A. Liquid biopsies: Genotyping circulating tumor DNA. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, T.; Matsuda, A.; Koizumi, M.; Shinji, S.; Takahashi, G.; Iwai, T.; Takeda, K.; Ueda, K.; Yokoyama, Y.; Hara, K.; et al. Liquid Biopsy for the Management of Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Digestion 2019, 99, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; He, W.; Wang, N.; Xi, Z.; Deng, R.; Liu, X.; Kang, R.; Xie, L. Application of Microfluidics in Detection of Circulating Tumor Cells. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 907232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, S.G.; Ahmad, M.R.; Koloor, S.S.R.; Petrů, M. Separation of ctDNA by superparamagnetic bead particles in microfluidic platform for early cancer detection. J. Adv. Res. 2021, 33, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velpula, T.; Buddolla, V. Enhancing detection and monitoring of circulating tumor cells: Integrative approaches in liquid biopsy advances. J. Liq. Biopsy 2025, 8, 100297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalligosfyri, P.M.; Nikou, S.; Karteri, S.; Kalofonos, H.P.; Bravou, V.; Kalogianni, D.P. Rapid Multiplex Strip Test for the Detection of Circulating Tumor DNA Mutations for Liquid Biopsy Applications. Biosensors 2022, 12, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, M.; Ahmed, R.; Das, D.K.; Pramanik, D.D.; Dash, S.K.; Pramanik, A. Recent Advancements in the Application of Circulating Tumor DNA as Biomarkers for Early Detection of Cancers. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 10, 4740–4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.C.M.; Massie, C.; Garcia-Corbacho, J.; Mouliere, F.; Brenton, J.D.; Caldas, C.; Pacey, S.; Baird, R.; Rosenfeld, N. Liquid biopsies come of age: Towards implementation of circulating tumour DNA. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The biology The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367, eaau6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, K.; Chen, Y.; Wu, X.; Chen, Z.; Cao, K.; Tao, Y.; Chen, X.; Liao, J.; Zhou, J. Exosomes and Their Role in Cancer Progression. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 639159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Luo, X.; Huang, Y.; Xie, T.; Pilarsky, C.; Dang, Y.; Zhang, J. Microfluidic Technology for the Isolation and Analysis of Exosomes. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zhu, H.; Li, X. Advances in electrochemical biosensors for the detection of tumor-derived exosomes. Front. Chem. 2025, 13, 1556595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Li, Z.; Ge, S.; Mao, Y.; Cao, X.; Lu, D. A microfluidic chip using Au@SiO2 array–based highly SERS-active substrates for ultrasensitive detection of dual cervical cancer–related biomarkers. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2022, 414, 7659–7673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khonyoung, S.; Mangkronkaew, P.; Klayprasert, P.; Puangpila, C.; Palanisami, M.; Arivazhagan, M.; Jakmunee, J. Point-of-Care Detection of Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA) Using a Smartphone-Based, Label-Free Electrochemical Immunosensor with Multilayer CuONPs/CNTs/GO on a Disposable Screen-Printed Electrode. Biosensors 2024, 14, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.; Cai, G.; Gao, Z.; Liang, C.; Yang, F.; Dou, X.; Jia, C.; Zhao, J.; Feng, S.; Li, B. A microfluidic immunosensor for automatic detection of carcinoembryonic antigen based on immunomagnetic separation and droplet arrays. Analyst 2023, 148, 1939–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Wang, T.; Gao, Y.; Tao, Q.; Ye, W.; Jia, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Z. Multiplexed immunosensing of cancer biomarkers on a split-float-gate graphene transistor microfluidic biochip. Lab Chip 2024, 24, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, M.A.; Schlessinger, J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell 2010, 141, 1117–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.H.; Williams, G.A.; Sridhara, R.; Chen, G.; Pazdur, R. FDA drug approval summary: Gefitinib (ZD1839) (Iressa) tablets. Oncologist 2003, 8, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, R.M.; Shastri, K.A.; Cohen, M.H.; Keegan, P.; Pazdur, R. FDA drug approval summary: Panitumumab (Vectibix). Oncologist 2007, 12, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, D.; Humblet, Y.; Siena, S.; Khayat, D.; Bleiberg, H.; Santoro, A.; Bets, D.; Mueser, M.; Harstrick, A.; Verslype, C.; et al. Cetuximab monotherapy and cetuximab plus irinotecan in irinotecan-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.H.; Johnson, J.R.; Chen, Y.F.; Sridhara, R.; Pazdur, R. FDA drug approval summary: Erlotinib (Tarceva) tablets. Oncologist 2005, 10, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folprecht, G.; Gruenberger, T.; Bechstein, W.O.; Raab, H.R.; Lordick, F.; Hartmann, J.T.; Lang, H.; Frilling, A.; Stoehlmacher, J.; Weitz, J.; et al. Tumour response and secondary resectability of colorectal liver metastases following neoadjuvant chemotherapy with cetuximab: The CELIM randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weickhardt, A.J.; Price, T.J.; Chong, G.; Gebski, V.; Pavlakis, N.; Johns, T.G.; Azad, A.; Skrinos, E.; Fluck, K.; Dobrovic, A.; et al. Dual targeting of the epidermal growth factor receptor using the combination of cetuximab and erlotinib: Preclinical evaluation and results of the phase II DUX study in chemotherapy-refractory, advanced colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, R.D.; Adams, V.R.; Beardslee, T.; Medina, P. Afatinib for the treatment of. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2020, 26, 1461–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khelwatty, S.A.; Essapen, S.; Bagwan, I.; Green, M.; Seddon, A.M.; Modjtahedi, H. Co-expression of HER family members in patients with Dukes’ C and D colon cancer and their impacts on patient prognosis and survival. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, A.; Takehana, T.; Li, X.; Suzuki, S.; Kunitomo, K.; Iino, H.; Fujii, H.; Takeda, Y.; Dobashi, Y. Protein overexpression and gene amplification of HER-2 and EGFR in colorectal cancers: An immunohistochemical and fluorescent in situ hybridization study. Mod. Pathol. 2004, 17, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruszewski, W.J.; Rzepko, R.; Ciesielski, M.; Szefel, J.; Zieliński, J.; Szajewski, M.; Jasiński, W.; Kawecki, K.; Wojtacki, J. Expression of HER2 in colorectal cancer does not correlate with prognosis. Dis. Markers 2010, 29, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, D.O.; Chambers, G.; O’Grady, L.; Barry, K.M.; Waldron, R.P.; Bennani, F.; Eustace, P.W.; Tobbia, I. Is overexpression of HER-2 a predictor of prognosis in colorectal cancer? BMC Cancer 2009, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Guo, K.; Feng, G.; Shan, F.; Sun, L.; Zhang, K.; Shen, F.; Shen, M.; Ruan, S. Association between the overexpression of Her3 and clinical pathology and prognosis of colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis. Medicine 2018, 97, e12317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kountourakis, P.; Pavlakis, K.; Psyrri, A.; Rontogianni, D.; Xiros, N.; Patsouris, E.; Pectasides, D.; Economopoulos, T. Prognostic significance of HER3 and HER4 protein expression in colorectal adenocarcinomas. BMC Cancer 2006, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegra, C.J.; Rumble, R.B.; Hamilton, S.R.; Mangu, P.B.; Roach, N.; Hantel, A.; Schilsky, R.L. Extended RAS Gene Mutation Testing in Metastatic Colorectal Carcinoma to Predict Response to Anti-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Monoclonal Antibody Therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Provisional Clinical Opinion Update 2015. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Abbas, N.; Park, Y.; Park, K.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Shin, S. Ultrasensitive and highly selective detection of PIK3CA single point mutations in cell-free DNA with LNA-modified hairpin-shaped probe. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 2022, 355, 131309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Tu, Y.; Liu, P.; Tang, Y.; Wang, F.; Li, Z.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Ma, Y.; Gu, Y. Detection of colorectal cancer using a small molecular fluorescent probe targeted against c-Met. Talanta 2021, 226, 122128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobor, S.; Van Emburgh, B.O.; Crowley, E.; Misale, S.; Di Nicolantonio, F.; Bardelli, A. TGFα and amphiregulin paracrine network promotes resistance to EGFR blockade in colorectal cancer cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 6429–6438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gini, A.; Jansen, E.E.L.; Zielonke, N.; Meester, R.G.S.; Senore, C.; Anttila, A.; Segnan, N.; Mlakar, D.N.; de Koning, H.J.; Lansdorp-Vogelaar, I.; et al. Impact of colorectal cancer screening on cancer-specific mortality in Europe: A systematic review. Eur. J. Cancer 2020, 127, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, K. Colorectal cancer development and advances in screening. Clin. Interv. Aging 2016, 11, 967–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.G.; Boland, C.R. Colorectal Cancer in Persons Under Age 50: Seeking Causes and Solutions. Gastrointest. Endosc. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 30, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Ma, X.; Chakravarti, D.; Shalapour, S.; DePinho, R.A. Genetic and biological hallmarks of colorectal cancer. Genes. Dev. 2021, 35, 787–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, A.; Kumar, H.; Yazji, K.; Wireko, A.A.; Sivanandan Nagarajan, J.; Ghosh, B.; Nahas, A.; Morales Ojeda, L.; Anand, A.; Sharath, M.; et al. Effectiveness of artificial intelligence-assisted colonoscopy in early diagnosis of colorectal cancer: A systematic review. Int. J. Surg. 2023, 109, 946–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galoș, D.; Gorzo, A.; Balacescu, O.; Sur, D. Clinical Applications of Liquid Biopsy in Colorectal Cancer Screening: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Cells 2022, 11, 3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Fu, B.; Li, P.; Xu, W. Label-free MIP-SERS biosensor for sensitive detection of colorectal cancer biomarker. Talanta 2023, 258, 124461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakerian, N.; Darzi-Eslam, E.; Afsharnoori, F.; Bana, N.; Noorabad Ghahroodi, F.; Tarin, M.; Mard-Soltani, M.; Khalesi, B.; Hashemi, Z.S.; Khalili, S. Therapeutic and diagnostic applications of exosomes in colorectal cancer. Med. Oncol. 2024, 41, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksakhina, S.N.; Imyanitov, E.N. Cancer Therapy Guided by Mutation Tests: Current Status and Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemiwal, M.; Zhang, T.C.; Kumar, D. Enzyme immobilized nanomaterials as electrochemical biosensors for detection of biomolecules. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2022, 156, 110006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coker, O.O.; Liu, C.; Wu, W.K.K.; Wong, S.H.; Jia, W.; Sung, J.J.Y.; Yu, J. Altered gut metabolites and microbiota interactions are implicated in colorectal carcinogenesis and can be non-invasive diagnostic biomarkers. Microbiome 2022, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavakoli, H.; Mohammadi, S.; Li, X.; Fu, G. Microfluidic platforms integrated with nano-sensors for point-of-care bioanalysis. Trends Anal. Chem. 2022, 157, 116806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noreen, S.; Ishaq, I.; Saleem, M.H.; Ali, B.; Muhammad Ali, S.; Iqbal, J. Electrochemical biosensing in oncology: A review advancements and prospects for cancer diagnosis. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2025, 26, 2475581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kownacka, A.E.; Vegelyte, D.; Joosse, M.; Anton, N.; Toebes, B.J.; Lauko, J.; Buzzacchera, I.; Lipinska, K.; Wilson, D.A.; Geelhoed-Duijvestijn, N.; et al. Clinical Evidence for Use of a Noninvasive Biosensor for Tear Glucose as an Alternative to Painful Finger-Prick for Diabetes Management Utilizing a Biopolymer Coating. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 4504–4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildizhan, Y.; Driessens, K.; Tsao, H.S.K.; Boiy, R.; Thomas, D.; Geukens, N.; Hendrix, A.; Lammertyn, J.; Spasic, D. Detection of Breast Cancer-Specific Extracellular Vesicles with Fiber-Optic SPR Biosensor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Nesakumar, N.; Gopal, J.; Sivasubramanian, S.; Vedantham, S.; Rayappan, J.B.B. Clinical validation of electrochemical biosensor for the detection of methylglyoxal in subjects with type-2 diabetes mellitus. Bioelectrochemistry 2024, 155, 108601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.-H.; Chiang, C.-C.; Ren, F.; Tsai, C.-T.; Chou, Y.-S.; Chiu, C.-W.; Liao, Y.-T.; Neal, D.; Heldermon, C.D.; Rocha, M.G.; et al. A High-Sensitivity, Bluetooth-Enabled PCB Biosensor for HER2 and CA15-3 Protein Detection in Saliva: A Rapid, Non-Invasive Approach to Breast Cancer Screening. Biosensors 2025, 15, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Lozano, O.; García-Aparicio, P.; Raduly, L.-Z.; Estévez, M.C.; Berindan-Neagoe, I.; Ferracin, M.; Lechuga, L.M. One-Step and Real-Time Detection of microRNA-21 in Human Samples for Lung Cancer Biosensing Diagnosis. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 14659–14665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagdeve, S.N.; Suganthan, B.; Ramasamy, R.P. An electrochemical biosensor for the detection of microRNA-31 as a potential oral cancer biomarker. J. Biol. Eng. 2025, 19, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zonta, G.; Malagù, C.; Gherardi, S.; Giberti, A.; Pezzoli, A.; Togni, A.; Palmonari, C. Clinical Validation Results of an Innovative Non-Invasive Device for Colorectal Cancer Preventive Screening through Fecal Exhalation Analysis. Cancers 2020, 12, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Pan, Y.; Wu, S.; Sun, Z.; Wang, L.; Yang, J.; Yin, Y.; Li, G. Detection of colorectal cancer-derived exosomes based on covalent organic frameworks. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 169, 112638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Keulen, K.E.; Jansen, M.E.; Schrauwen, R.W.M.; Kolkman, J.J.; Siersema, P.D. Volatile organic compounds in breath can serve as a non-invasive diagnostic biomarker for the detection of advanced adenomas and colorectal cancer. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 51, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Shi, H.; Mu, B. Application of a Novel One-Side Cell Quartz Crystal Microbalance Immunosensor in the Determination of Alpha-Fetoprotein from Human Serum. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari Nakhjavani, S.; Mirzajani, H.; Carrara, S.; Onbaşlı, M.C. Advances in biosensor technologies for infectious diseases detection. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 180, 117979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, O.; Shamsi, M.H. Transformative biomedical devices to overcome biomatrix effects. Biosens Bioelectron 2025, 279, 117373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasser, L.R. Leveraging biosensors in clinical and research settings: A guide to device selection. NPP—Digit. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2025, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harms, R.L.; Ferrari, A.; Meier, I.B.; Martinkova, J.; Santus, E.; Marino, N.; Cirillo, D.; Mellino, S.; Catuara Solarz, S.; Tarnanas, I.; et al. Digital biomarkers and sex impacts in Alzheimer’s disease management-potential utility for innovative 3P medicine approach. EPMA J. 2022, 13, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenović, M.; Jarić, S.; Mundžić, M.; Pavlović, A.; Bobrinetskiy, I.; Knežević, N. Biosensors for Cancer Biomarkers Based on Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles. Biosensors 2024, 14, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Song, Y.; Deng, D.; Zhang, W.; Wang, T.; Luo, L. The Application of Functional Nanomaterials-Based Electrochemical Biosensors in Detecting Cancer Biomarkers: A Review. Molecules 2025, 30, 2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lino, C.; Barrias, S.; Chaves, R.; Adega, F.; Martins-Lopes, P.; Fernandes, J.R. Biosensors as diagnostic tools in clinical applications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2022, 1877, 188726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan Nair Sudha Kumari, S.; Thankappan Suryabai, X. Sensing the Future-Frontiers in Biosensors: Exploring Classifications, Principles, and Recent Advances. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 48918–48987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Alton, L.; Souto, D.; Punyadeera, C.; Abbey, B.; Voelcker, N.; Hogan, C.; Silva, S. A holistic pathway to biosensor translation. Sens. Diagn. 2024, 3, 1234–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Rai, S.; Bandopadhyay, A.; Das, M. From detection to drug delivery: Innovations in cancer biosensors from concept to clinical impact. Biotechnol. Sustain. Mater. 2025, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotan, D.; Eliahou, O.; Cohen, S. Serial and syntactic processing in the visual analysis of multi-digit numbers. Cortex 2021, 134, 162–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, M. Editorial. J. Anal. Psychol. 2020, 65, 257–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, J.; Xie, W.; Wan, B.; Huo, T.B.; Lin, W.P.; Liu, J.; Jin, C.H. Heat-induced tolerance to browning of fresh-cut lily bulbs (Lilium lancifolium Thunb.) under cold storage. J. Food Biochem. 2019, 43, e12816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasilewski, T.; Kamysz, W.; Gębicki, J. AI-Assisted Detection of Biomarkers by Sensors and Biosensors for Early Diagnosis and Monitoring. Biosensors 2024, 14, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poona, N.K.; van Niekerk, A.; Nadel, R.L.; Ismail, R. Random Forest (RF) Wrappers for Waveband Selection and Classification of Hyperspectral Data. Appl. Spectrosc. 2016, 70, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Wagle, N.S.; Cercek, A.; Smith, R.A.; Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 233–254. [Google Scholar]

- Ladabaum, U.; Dominitz, J.A.; Kahi, C.; Schoen, R.E. Strategies for Colorectal Cancer Screening. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 418–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperiale, T.F.; Ransohoff, D.F.; Itzkowitz, S.H.; Levin, T.R.; Lavin, P.; Lidgard, G.P.; Ahlquist, D.A.; Berger, B.M. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1287–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayanthi, V.S.P.K.; Das, A.B.; Saxena, U. Recent advances in biosensor development for the detection of cancer biomarkers. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 91, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leemans, C.R.; Snijders, P.J.F.; Brakenhoff, R.H. The molecular landscape of head and neck cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Non Modifiable Risk Factors | Modifiable Risk Factors |

|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Sedentary lifestyle |

| Sex | Obesity |

| Age | Diet |

| Hereditary mutations | Smoking |

| Inflammatory bowel diseases | Alcohol consumption |

| Cystic fibrosis | Diabetes and insulin resistance |

| Acromegaly | Gut microbiota |

| Cholecystectomy | |

| Treatment with androgen derivatives |

| Stage | Tumor (T) | Lymph Nodes (N) | Metastasis (M) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 | Early cancer limited to the innermost lining (carcinoma in situ). |

| I | T1 or T2 | N0 | M0 | Tumor has penetrated the inner layers of the bowel wall but not the lymph nodes or distant organs. |

| IIA | T3 | N0 | M0 | Tumor has extended into the outer layers of the colon/rectum without breaking through. |

| IIB | T4a | N0 | M0 | Tumor has broken through the outer wall but has not invaded nearby organs. |

| IIC | T4b | N0 | M0 | Tumor has grown into or adhered to nearby structures or organs. |

| IIIA | T1–T2 or T1 | N1/N1c or N2a | M0 | Tumor has invaded inner layers and spread to a few nearby lymph nodes or surrounding fat. |

| IIIB | T3–T4a or T2–T3 or T1–T2 | N1/N1c or N2a or N2b | M0 | Tumor extends through outer layers and has spread to multiple nearby lymph nodes. |

| IIIC | T4a or T3–T4a or T4b | N2a or N2b or N1/N2 | M0 | Advanced local tumor spread and significant lymph node involvement, but no distant metastasis. |

| IVA | Any T | Any N | M1a | Cancer has spread to a single distant organ or lymph node group. |

| IVB | Any T | Any N | M1b | Cancer has spread to more than one distant organ or lymph node group. |

| IVC | Any T | Any N | M1c | Cancer has spread to the lining of the abdominal cavity (peritoneum), possibly with other distant spread. |

| Method | Description | Time to Result | Purpose | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fecal Occult Blood Test (FOBT) [75] | A stool-based test detecting heme in hemoglobin via guaiac resin reaction. Requires dietary restrictions to reduce false positives. | 1–7 days | Early detection of hidden (occult) blood indicating possible CRC or polyps. | Annual screening; limited sensitivity multiple samples needed. |

| Fecal Immunochemical Test (FIT) [9] | Uses antibodies to detect human hemoglobin; more specific to lower GI bleeding. No dietary restrictions required. | 1–3 days | Preferred stool-based test for early CRC detection. | Annual screening; higher specificity than gFOBT; single sample sufficient. |

| Colonoscopy [75] | Direct visualization of colon via a flexible scope. Allows detection and removal of polyps and biopsy. High-definition imaging and chromoendoscopy can enhance detection. | Immediate (preliminary); biopsy results: 3–7 days | Gold standard for both screening and diagnosis of CRC and colonic diseases. | Every 10 years for average risk; requires bowel prep and sedation; risks include perforation and bleeding. |

| Flexible Sigmoidoscopy [9] | Endoscopic exam of rectum and lower colon (up to ~60 cm). No sedation is typically required. Can remove polyps and biopsy tissue. | Immediate (preliminary); biopsy results: 3–7 days | Screening tool especially for distal colon lesions. | Less invasive than colonoscopy; performed every 5 years. Limited to lower colon. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Georgoulia, K.K.; Tsekouras, V.; Mavrikou, S. Advances in Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Gender and Sex Differences in Biomarkers and Their Perspectives for Novel Biosensing Detection Methods. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010013

Georgoulia KK, Tsekouras V, Mavrikou S. Advances in Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Gender and Sex Differences in Biomarkers and Their Perspectives for Novel Biosensing Detection Methods. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeorgoulia, Konstantina K., Vasileios Tsekouras, and Sofia Mavrikou. 2026. "Advances in Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Gender and Sex Differences in Biomarkers and Their Perspectives for Novel Biosensing Detection Methods" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010013

APA StyleGeorgoulia, K. K., Tsekouras, V., & Mavrikou, S. (2026). Advances in Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Gender and Sex Differences in Biomarkers and Their Perspectives for Novel Biosensing Detection Methods. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010013