Cytopenias as Adverse Drug Reactions: A 10-Year Analysis of Reporting Structure, Rate, and Trend

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Adverse Reaction Reporting Structure

2.1.1. Leucopenia

2.1.2. Anemia

2.1.3. Thrombocytopenia

2.1.4. Cytopenias in Total

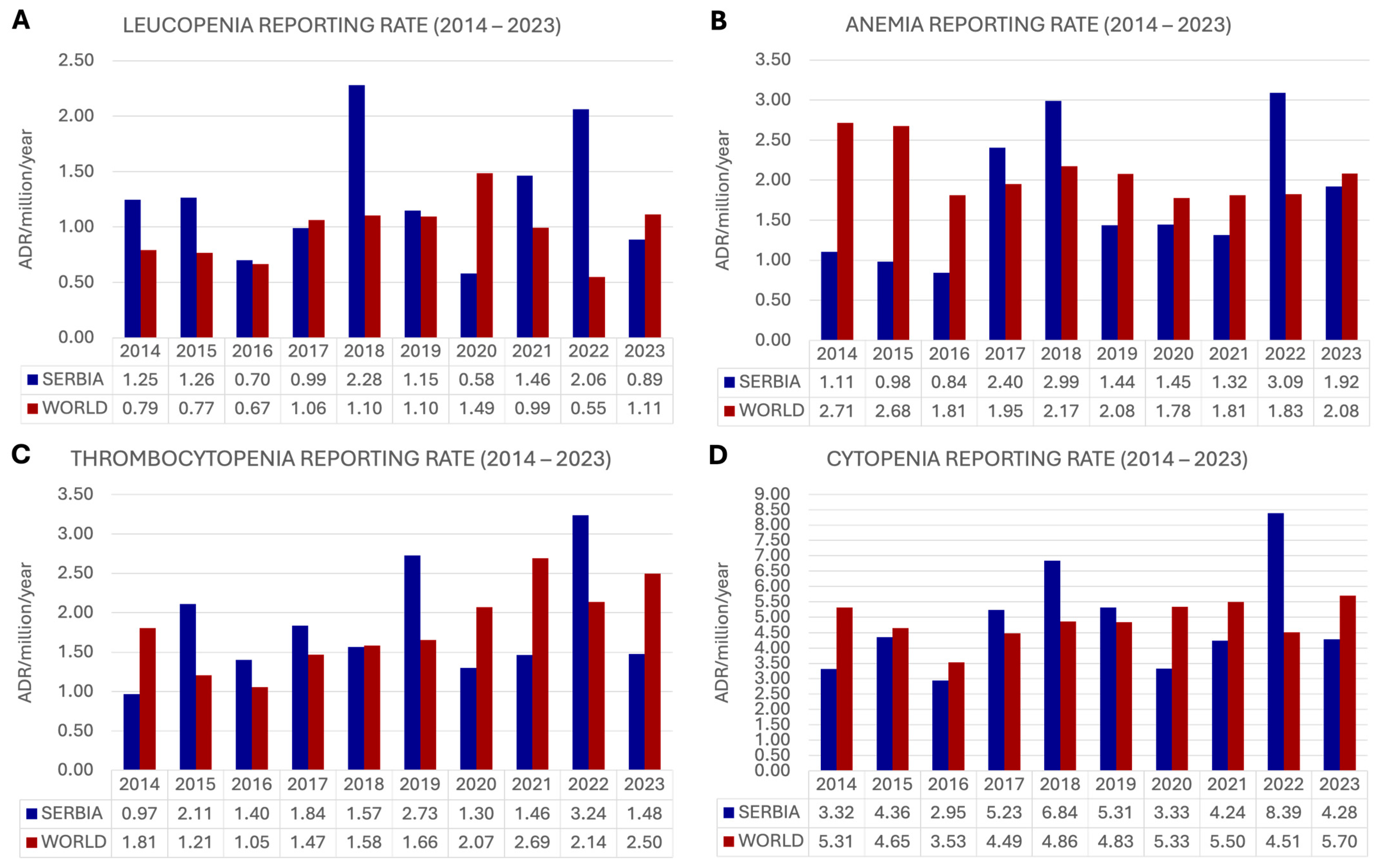

2.2. Adverse Reaction Reporting Rate

2.2.1. Leucopenia

2.2.2. Anemia

2.2.3. Thrombocytopenia

2.2.4. Cytopenia in Total

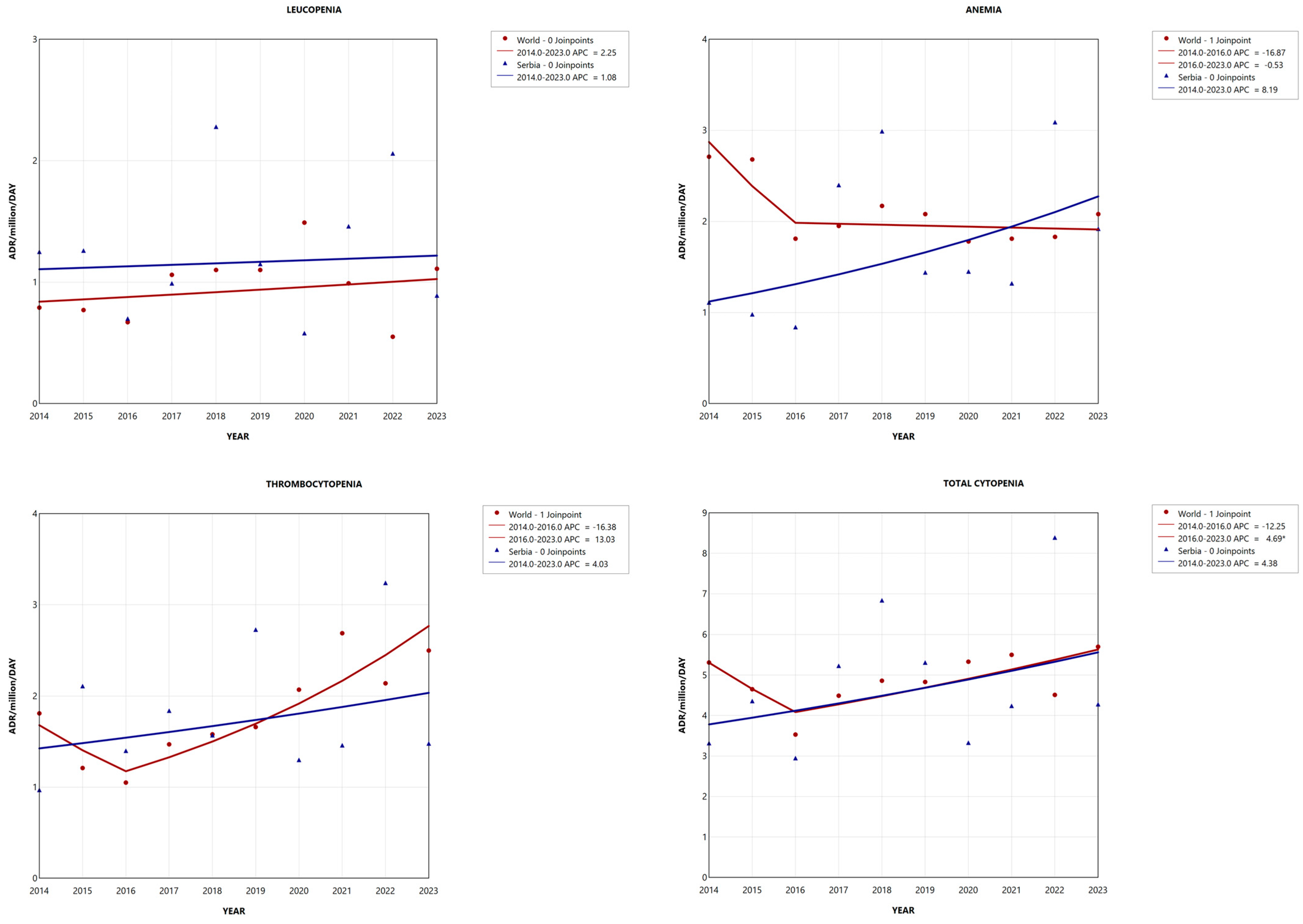

2.3. Adverse Reaction Reporting Trend

2.3.1. Leucopenia

2.3.2. Anemia

2.3.3. Thrombocytopenia

2.3.4. Cytopenia in Total

3. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Term Cytopenia. NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/cytopenia (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Guideline on Haemoglobin Cutoffs to Define Anaemia in Individuals and Populations; World Health Organization: Geneva, Swizerland, 2024.

- Dean, L. Blood Groups and Red Cell Antigens. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2005. Table 1, Complete Blood Count. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2263/table/ch1.T1/ (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Cytopenia. Available online: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/24864-cytopenia (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Onuoha, C.; Arshad, J.; Astle, J.; Xu, M.; Halene, S. Novel Developments in Leukopenia and Pancytopenia. Prim Care 2016, 43, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ing, V.W. The etiology and management of leukopenia. Can. Fam. Physician 1984, 30, 1835–1839. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tisdale, J.E.; Miller, D.A. (Eds.) Drug-Induced Diseases, 3rd ed.; American Society of Health-System Pharmacists: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2018.

- Bakchoul, T.; Marini, I. Drug-associated thrombocytopenia. Hematol. ASH Educ. Program 2018, 2018, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, B.R. Non-chemotherapy drug-induced neutropenia: Key points to manage the challenges. Hematol. ASH Educ. Program 2017, 2017, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camitta, B.M.; Thomas, E.D.; Nathan, D.G.; Gale, R.P.; Kopecky, K.J.; Rappeport, J.M.; Santos, G.; Gordon-Smith, E.C.; Storb, R. A prospective study of androgens and bone marrow transplantation for treatment of severe aplastic anemia. Blood 1979, 53, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, B.; Bartolmäs, T.; Yürek, S.; Salama, A. Variability of Findings in Drug-Induced Immune Haemolytic Anaemia: Experience over 20 Years in a Single Centre. Transfus. Med. Hemotherapy 2015, 42, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, J.; Cutroneo, P.; Trifirò, G. Clinical and economic burden of adverse drug reactions. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2013, 4, S73–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.A.; Bootman, J.L. Drug-related morbidity and mortality. A cost-of-illness model. Arch. Intern. Med. 1995, 155, 1949–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu, S.F.; Shafie, A.A.; Chandriah, H. Cost Estimations of Managing Adverse Drug Reactions in Hospitalized Patients: A Systematic Review of Study Methods and Their Influences. Pharmacoepidemiology 2023, 2, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elalamy, I.; Le Gal, G.; Nachit-Ouinekh, F.; Lafuma, A.; Emery, C.; Le-Fur, C.; Chapuis, F. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: An estimate of the average cost in the hospital setting in France. Clin. Appl. Thromb./Hemost. 2009, 15, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottenkolber, D.; Hasford, J.; Stausberg, J. Costs of Adverse Drug Events in German Hospitals—A Microcosting Study. Value Heal. 2012, 15, 868–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, P.G.M.; Arnardottir, A.H.; Motola, D.; Vrijlandt, P.J.; Duijnhoven, R.G.; Haaijer-Ruskamp, F.M.; de Graeff, P.A.; Denig, P.; Straus, S.M.J.M. Post-Approval Safety Issues with Innovative Drugs: A European Cohort Study. Drug Saf. 2013, 36, 1105–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medicines Approval System. Available online: https://www.hma.eu/about-hma/medicines-approval-system/medicines-approval-system.html (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Crescioli, G.; Bonaiuti, R.; Corradetti, R.; Mannaioni, G.; Vannacci, A.; Lombardi, N. Pharmacovigilance and Pharmacoepidemiology as a Guarantee of Patient Safety: The Role of the Clinical Pharmacologist. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Gonzalez, E.; Herdeiro, M.T.; Figueiras, A. Determinants of under-reporting of adverse drug reactions: A systematic review. Drug Saf. 2009, 32, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herdeiro, M.T.; Figueiras, A.; Polónia, J.; Gestal-Otero, J.J. Physicians’ attitudes and adverse drug reaction reporting. Drug Saf. 2005, 28, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Abeijon, P.; Costa, C.; Taracido, M.; Herdeiro, M.T.; Torre, C.; Figueiras, A. Factors Associated with Underreporting of Adverse Drug Reactions by Health Care Professionals: A Systematic Review Update. Drug Saf. 2023, 46, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIOMS Cumulative Glossary with a Focus on Pharmacovigilance, Version 2.3; Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS): Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Guideline on Good Pharmacovigilance Practices (GVP) Module I—Pharmacovigilance Systems and Their Quality Systems; European Medicines Agency: London, UK, 2012.

- The Importance of Pharmacovigilance: Safety Monitoring of Medicinal Products; World Health Organization: Geneva, Swizerland, 2002.

- Thiessard, F.; Roux, E.; Miremont-Salamé, G.; Fourrier-Réglat, A.; Haramburu, F.; Tubert-Bitter, P.; Bégaud, B. Trends in Spontaneous Adverse Drug Reaction Reports to the French Pharmacovigilance System (1986–2001). Drug Saf. 2005, 28, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Yousef, N.; Yenugadhati, N.; Alqahtani, N.; Alshahrani, A.; Alshahrani, M.; Al Jeraisy, M.; Badri, M. Patterns of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm. J. 2021, 30, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubrall, D.; Just, K.S.; Schmid, M.; Stingl, J.C.; Sachs, B. Adverse drug reactions in older adults: A retrospective comparative analysis of spontaneous reports to the German Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2020, 21, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakare, V.; Patil, A.; Jain, M.; Rai, V.; Langade, D. Adverse drug reactions reporting: Five years analysis from a teaching hospital. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 7316–7321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, P.; Dubrall, D.; Schmid, M.; Sachs, B. Comparative Analysis of Information Provided in German Adverse Drug Reaction Reports Sent by Physicians, Pharmacists and Consumers. Drug Saf. 2023, 46, 1363–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.M.; Shin, W.G.; Lee, J.-Y.; Choi, S.A.; Jo, Y.H.; Youn, S.J.; Lee, M.S.; Choi, K.H. Patterns of Adverse Drug Reactions in Different Age Groups: Analysis of Spontaneous Reports by Community Pharmacists. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montané, E.; Sanz, Y.; Martin, S.; Pérez-Mañá, C.; Papaseit, E.; Hladun, O.; De la Rosa, G.; Farré, M. Spontaneous adverse drug reactions reported in a thirteen-year pharmacovigilance program in a tertiary university hospital. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1427772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Lin, Y.; Ren, W.; Fang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Tan, X.; Lv, X.; Zhang, N. Adverse drug reactions and correlations with drug–drug interactions: A retrospective study of reports from 2011 to 2020. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 923939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuka, J.T.; Khoza, S. An analysis of the trends, characteristics, scope, and performance of the Zimbabwean pharmacovigilance reporting scheme. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2020, 8, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, M.R.; Monteiro, C.; Pereira, L.; Duarte, A.P. Quality of Spontaneous Reports of Adverse Drug Reactions Sent to a Regional Pharmacovigilance Unit. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, G.; Aykac, E.; Kasap, Y.; Nemutlu, N.T.; Sen, E.; Aydinkarahaliloglu, N.D. Adverse Drug Reaction Reporting Pattern in Turkey: Analysis of the National Database in the Context of the First Pharmacovigilance Legislation. Drugs-Real World Outcomes 2016, 3, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aagaard, L.; Strandell, J.; Melskens, L.; Petersen, P.S.; Holme Hansen, E. Global patterns of adverse drug reactions over a decade: Analyses of spontaneous reports to VigiBase™. Drug Saf. 2012, 35, 1171–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademaker, M. Do Women Have More Adverse Drug Reactions? Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2001, 2, 349–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazzara, M.B.; Palmer, K.; Vetrano, D.L.; Carfì, A.; Onder, G. Adverse drug reactions in older adults: A narrative review of the literature. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 12, 463–473, Erratum in Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2022, 13, 307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-021-00591-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bégaud, B.; Martin, K.; Fourrier, A.; Haramburu, F. Does age increase the risk of adverse drug reactions? Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2002, 54, 550–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolezzi, M.; Parsotam, N. Adverse drug reaction reporting in New Zealand: Implications for pharmacists. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2005, 1, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Annual Reports of Spontaneous Adverse Drug Reactions Reporting (2014–2023). Available online: https://www.alims.gov.rs/farmakovigilanca/godisnji-izvestaji/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Lemozit, J.P.; DE LA Rhodiere, G.P.; Lapeyre-Mestre, M.; Bagheri, H.; Montastruc, J.L. A comparative study of adverse drug reactions reported through hospital and private medicine. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1996, 41, 166–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farber, A.J.; Suarez, K.; Slicker, K.; Patel, C.D.; Pope, B.; Kowal, R.; Michel, J.B. Frequency of Troponin Testing in Inpatient Versus Outpatient Settings. Am. J. Cardiol. 2017, 119, 1153–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, J.; Hefner, G.; Normann, C.; Kaier, K.; Binder, H.; Hiemke, C.; Toto, S.; Domschke, K.; Marschollek, M.; Klimke, A. Polypharmacy and the risk of drug–drug interactions and potentially inappropriate medications in hospital psychiatry. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2021, 30, 1258–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.; Terrence, J.; Vasquez, P.; Bates, D.W.; Zimlichman, E. Continuous Monitoring in an Inpatient Medical-Surgical Unit: A Controlled Clinical Trial. Am. J. Med. 2014, 127, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, J.; Tsuyuki, R.T.; Al Hamarneh, Y.N.; Bajorek, B. Barriers to a full scope of pharmacy practice in primary care: A systematic review of pharmacists’ access to laboratory testing. Can. Pharm. J./Rev. des Pharm. du Can. 2019, 152, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoro, R.N.; Nduaguba, S.O. Community pharmacists on the frontline in the chronic disease management: The need for primary healthcare policy reforms in low and middle income countries. Explor. Res. Clin. Soc. Pharm. 2021, 2, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, V.; Tharmalingam, S.; Cooper, J.; Charlebois, M. Canadian community pharmacists’ use of digital health technologies in practice. Can. Pharm. J./Rev. des Pharm. du Can. 2015, 149, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hamarneh, Y.N.; Hemmelgarn, B.; Curtis, C.; Balint, C.; Jones, C.A.; Tsuyuki, R.T. Community pharmacist targeted screening for chronic kidney disease. Can. Pharm. J./Rev. des Pharm. du Can. 2015, 149, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, S.K.; S., G.; Kamble, S. A Prospective, Observational Study of the Spontaneous Reporting Patterns of Adverse Drug Reactions in a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2022, 13, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). Available online: https://fis.fda.gov/sense/app/95239e26-e0be-42d9-a960-9a5f7f1c25ee/sheet/7a47a261-d58b-4203-a8aa-6d3021737452/state/analysis (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Rolfes, L.; Haaksman, M.; van Hunsel, F.; van Puijenbroek, E. Insight into the Severity of Adverse Drug Reactions as Experienced by Patients. Drug Saf. 2019, 43, 291–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alomar, M.; Tawfiq, A.M.; Hassan, N.; Palaian, S. Post marketing surveillance of suspected adverse drug reactions through spontaneous reporting: Current status, challenges and the future. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2020, 11, 2042098620938595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stević, I.; Janković, S.M.; Petrović, N.; Čanak-Baltić, N.; Marinković, V.; Lakić, D. Nonchemotherapy drug—induced cytopenias: A cost of illness study using the microcosting methodology based on real—world data. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindquist, M.; Edwards, I.R. Adverse drug reaction reporting in Europe: Some problems of comparison. Int. J. Risk Saf. Med. 1993, 4, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garashi, H.Y.; Steinke, D.T.; Schafheutle, E.I. A Systematic Review of Pharmacovigilance Systems in Developing Countries Using the WHO Pharmacovigilance Indicators. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 2022, 56, 717–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, S.S.; Bpharm, J.J.G.; Heaton, P.C.; Steinbuch, M. Overview and Comparison of Postmarketing Drug Safety Surveillance in Selected Developing and Well-Developed Countries. Drug Inf. J. 2010, 44, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, A.; Sridhar, S.B.; Rabbani, S.A.; Shareef, J.; Wadhwa, T. Exploring pharmacovigilance practices and knowledge among healthcare professionals: A cross-sectional multicenter study. SAGE Open Med. 2024, 12, 20503121241249908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caveat Document, Version: 2025-03-14. Available online: https://who-umc.org/media/yzpnzmdv/umc_caveat.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Guideline for Using VigiBase Data in Studies. Uppsala Monitoring Center. Available online: https://who-umc.org/media/05kldqpj/guidelineusingvigibaseinstudies.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac, version 29; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- World Population (2014–2023). Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/world-population-by-year/ (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Population in Serbia (2014–2023). Available online: https://data.stat.gov.rs/Home/Result/180107?languageCode=sr-Latn (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Joinpoint Regression Software, Version 5.4.0. Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute: Rockville, MD, USA, 2025.

- Kader, G.D.; Perry, M. Variability for Categorical Variables. J. Stat. Educ. 2007, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reporting Structure Category | World N (%) | Serbia N (%) | World N (%) | Serbia N (%) | World N (%) | Serbia N (%) | World N (%) | Serbia N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADR TYPE | Leucopenia | Anemia | Thrombocytopenia | Total Cytopenia | ||||

| Number of reported ADR | N = 74,873 | N = 88 | N = 161,631 | N = 122 | N = 141,836 | N = 126 | N = 378,340 | N = 336 |

| PATIENT AGE | χ2 = 22.606 *; p = 0.003; w = 0.02 | χ2 = 29.975 *; p < 0.001; w = 0.01 | χ2 = 27.381 *; p < 0.001; w = 0.01 | χ2 = 63.295 *; p < 0.001; w = 0.01 | ||||

| Children (<18 years) | 2612 (3.48) | 3 (3.41) | 4534 (2.81) | 2 (1.64) | 6285 (4.43) | 2 (1.59) | 13,431 (3.54) | 7 (2.08) |

| Adults (18–64 years) | 37,456 (50.03) | 56 (63.63) | 62,840 (38.87) | 74 (60.66) | 61,205 (43.15) | 71 (56.35) | 161,501 (42.69) | 201 (59.82) |

| Elderly (≥65 years) | 19,630 (26.22) | 10 (11.37) | 60,731 (37.58) | 33 (27.05) | 53,846 (37.95) | 29 (23.02) | 134,189 (35.47) | 72 (21.43) |

| Unknown | 15,175 (20.27) | 19 (21.59) | 33,526 (20.74) | 13 (10.66) | 20,518 (14.47) | 24 (19.05) | 69,219 (18.30) | 56 (16.67) |

| SEX | χ2 = 7.218; p = 0.027; w = 0.01 | χ2 = 8.606 **; p = 0.013; w = 0.01 | χ2 = 10.552 **; p = 0.005; w = 0.01 | χ2 = 15.664; p = 0.00; w = 0.01 | ||||

| Female | 43,139 (57.62) | 57 (64.77) | 88,291 (54.63) | 81 (66.39) | 62,828 (44.29) | 69 (54.76) | 194,258 (51.34) | 207 (61.61) |

| Male | 29,388 (39.25) | 25 (28.41) | 64,103 (39.66) | 39 (31.97) | 70,816 (49.92) | 56 (44.44) | 164,307 (43.43) | 120 (35.71) |

| Unknown | 2346 (3.13) | 6 (6.82) | 9237 (5.71) | 2 (1.64) | 8201 (5.78) | 1 (0.79) | 19,784 (5.23) | 9 (2.68) |

| SERIOUS | χ2 = 40.729 **; p < 0.001; w = 0.02 | χ2 = 2.175 **; p = 0.292; w = 0.00 | χ2 = 6.521 *; p = 0.034; w = 0.00 | χ2 = 27.376 *; p = 0.000; w = 0.01 | ||||

| Yes | 34,138 (45.59) | 69 (78.41) | 110,393 (68.30) | 91 (74.59) | 111,698 (78.75) | 111 (88.10) | 256,229 (67.72) | 271 (80.65) |

| No | 40,095 (53.55) | 18 (20.45) | 49,651 (30.72) | 30 (24.59) | 28,608 (20.17) | 15 (11.90) | 118,354 (31.28) | 63 (18.75) |

| Unknown | 640 (0.85) | 1 (1.14) | 1587 (0.98) | 1 (0.82) | 1530 (1.08) | 0 (0.00) | 3757 (0.99) | 2 (0.60) |

| SERIOUSNESS CRITERIA | χ2 = 2.267 *; p = 0.748; w = 0.01 | χ2 = 11.844 **; p = 0.034; w = 0.01 | χ2 = 15.371 *; p = 0.008; w = 0.01 | χ2 = 29.129 **; p = 0.000; w = 0.01 | ||||

| Death | 1563 (3.99) | 4 (4.71) | 8941 (6.31) | 7 (5.43) | 7377 (7.22) | 9 (6.57) | 17,881 (6.31) | 20 (5.70) |

| Life threatening | 2310 (5.89) | 5 (5.88) | 7701 (5.43) | 4 (3.10) | 7853 (7.68) | 6 (4.38) | 17,864 (6.31) | 15 (4.27) |

| Caused/prolonged hospitalization | 11,312 (28.84) | 21 (24.71) | 63,680 (44.92) | 46 (35.66) | 35,395 (34.64) | 31 (22.63) | 110,387 (38.98) | 98 (27.92) |

| Disabling/incapacitating | 279 (0.71) | 1 (1.18) | 2440 (1.72) | 2 (1.55) | 1229 (1.20) | 1 (0.73) | 3948 (1.39) | 4 (1.14) |

| Congenital anomaly/birth defect | 59 (0.15) | 0 (0.00) | 172 (0.12) | 1 (0.78) | 109 (0.11) | 0 (0.00) | 340 (0.12) | 1 (0.28) |

| Other medically important condition | 23,696 (60.42) | 54 (63.53) | 58,825 (41.50) | 69 (53.49) | 50,230 (49.15) | 90 (65.69) | 132,751 (46.88) | 213 (60.68) |

| REPORTER QUALIFICATION | χ2 = 190.042 *; p < 0.001; w = 0.03 | χ2 = 85.014 *; p < 0.001; w = 0.02 | χ2 = 122.737 *; p < 0.001; w = 0.02 | χ2 = 370.128 **; p < 0.001; w = 0.03 | ||||

| Physician | 28,375 (15.94) | 66 (73.33) | 75,730 (42.72) | 104 (81.89) | 57,536 (37.30) | 101 (73.19) | 161,641 (31.72) | 271 (76.34) |

| Pharmacist | 9883 (5.55) | 2 (2.22) | 18,862 (10.64) | 3 (2.36) | 16,422 (10.65) | 1 (0.72) | 45,167 (8.86) | 6 (1.69) |

| Other Health Professional | 33,238 (18.67) | 14 (15.56) | 28,999 (16.36) | 11 (8.66) | 22,429 (14.54) | 26 (18.84) | 84,666 (16.62) | 51 (14.37) |

| Lawyer | 14,080 (7.91) | 0 (0.00) | 780 (0.44) | 1 (0.79) | 173 (0.11) | 0 (0.00) | 15,033 (2.95) | 1 (0.28) |

| Consumer/Non Health Professional | 3415 (1.92) | 6 (6.67) | 41,253 (23.27) | 6 (4.72) | 16,317 (10.58) | 9 (6.52) | 60,985 (11.97) | 21 (5.92) |

| Unknown | 89,052 (50.02) | 2 (2.22) | 11,661 (6.58) | 2 (1.57) | 41,357 (26.81) | 1 (0.72) | 142,070 (27.88) | 5 (1.41) |

| ADR Type | Area | Average | Standard Deviation | Maximum | Minimum | Median | 95% CI [Lower–Upper Limits] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LEUCOPENIA | Global | 0.96 | 0.27 | 1.49 | 0.55 | 1.03 | 0.20 [0.77–1.16] |

| Serbia | 1.26 | 0.55 | 2.28 | 0.58 | 1.20 | 0.39 [0.87–1.66] | |

| ANEMIA | Global | 2.09 | 0.35 | 2.71 | 1.78 | 2.02 | 0.25 [1.84–2.34] |

| Serbia | 1.75 | 0.82 | 3.09 | 0.84 | 1.44 | 0.58 [1.17–2.34] | |

| THROMBOCYTOPENIA | Global | 1.82 | 0.53 | 2.69 | 1.05 | 1.73 | 0.38 [1.44–2.20] |

| Serbia | 1.81 | 0.70 | 3.24 | 0.97 | 1.52 | 0.50 [1.31–2.31] | |

| TOTAL CYTOPENIA | Global | 4.87 | 0.63 | 5.70 | 3.53 | 4.85 | 0.45 [4.42–5.32] |

| Serbia | 4.83 | 1.70 | 8.39 | 2.95 | 4.32 | 1.22 [3.61–6.04] |

| Criteria for Unalikeability Difference * | Area | Leucopenia | Anemia | Thrombocytopenia | Total Cytopenia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥10% | World | 0.40 | 0.32 | 0.44 | 0.28 |

| Serbia | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.44 | |

| ≥15% | World | 0.37 | 0.24 | 0.40 | 0.22 |

| Serbia | 0.41 | 0.43 | 0.38 | 0.42 | |

| ≥20% | World | 0.34 | 0.18 | 0.34 | 0.12 |

| Serbia | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.34 | 0.36 | |

| ≥25% | World | 0.31 | 0.13 | 0.29 | 0.08 |

| Serbia | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.26 | |

| ≥30% | World | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.23 | 0.04 |

| Serbia | 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.26 | |

| ≥35% | World | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.02 |

| Serbia | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.19 | 0.22 | |

| ≥40% | World | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.00 |

| Serbia | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.12 | |

| ≥45% | World | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.00 |

| Serbia | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.10 | |

| ≥50% | World | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 |

| Serbia | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Stević, I.; Janković, S.M.; Mihailović, M.; Jović, I.; Odalović, M.; Marinković, V.; Lakić, D. Cytopenias as Adverse Drug Reactions: A 10-Year Analysis of Reporting Structure, Rate, and Trend. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010014

Stević I, Janković SM, Mihailović M, Jović I, Odalović M, Marinković V, Lakić D. Cytopenias as Adverse Drug Reactions: A 10-Year Analysis of Reporting Structure, Rate, and Trend. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleStević, Ivana, Slobodan M. Janković, Marija Mihailović, Ivana Jović, Marina Odalović, Valentina Marinković, and Dragana Lakić. 2026. "Cytopenias as Adverse Drug Reactions: A 10-Year Analysis of Reporting Structure, Rate, and Trend" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010014

APA StyleStević, I., Janković, S. M., Mihailović, M., Jović, I., Odalović, M., Marinković, V., & Lakić, D. (2026). Cytopenias as Adverse Drug Reactions: A 10-Year Analysis of Reporting Structure, Rate, and Trend. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010014