Gene and Protein Profiles of CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

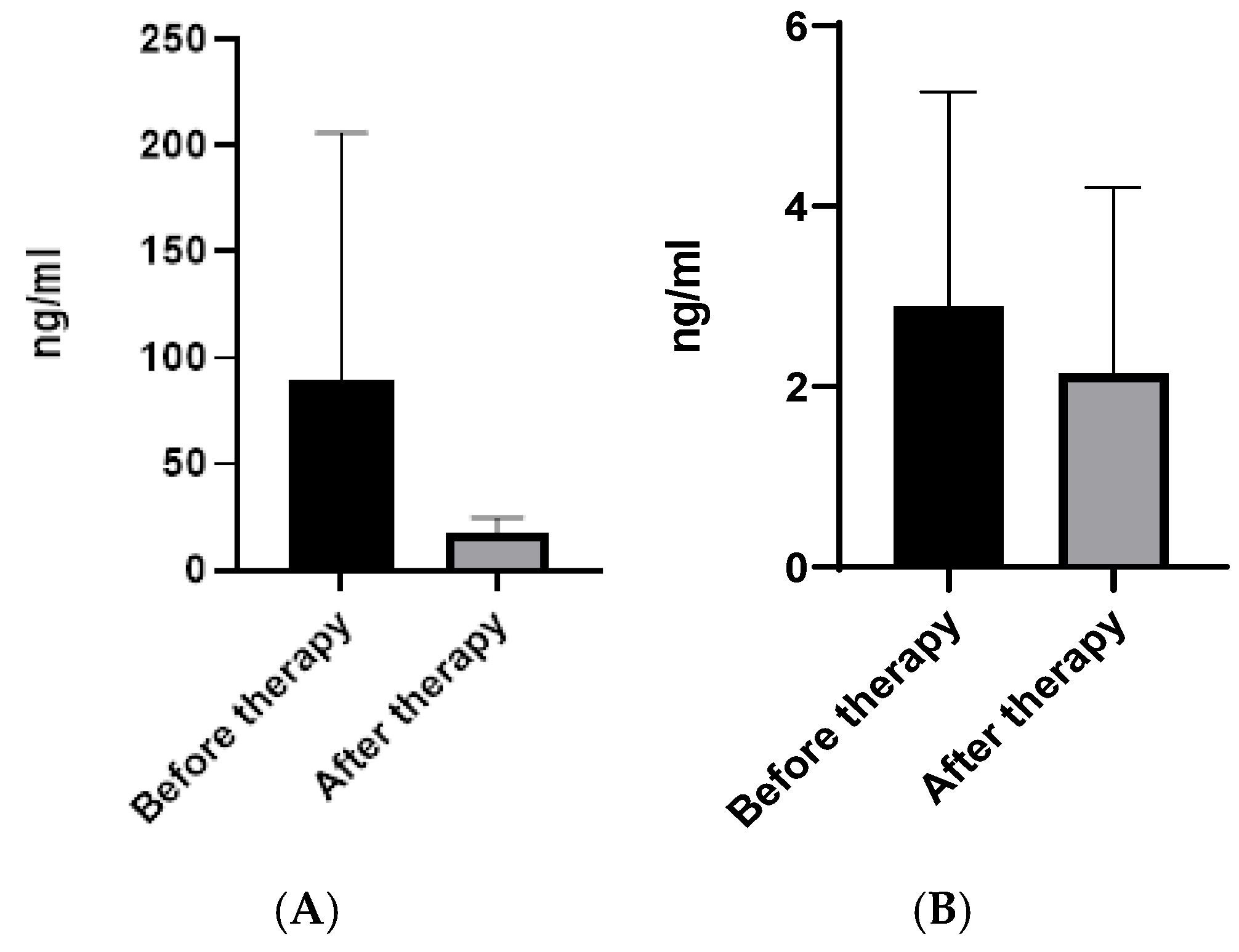

2.1. CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 Protein and Gene Levels in Patients on Different Therapy Protocols

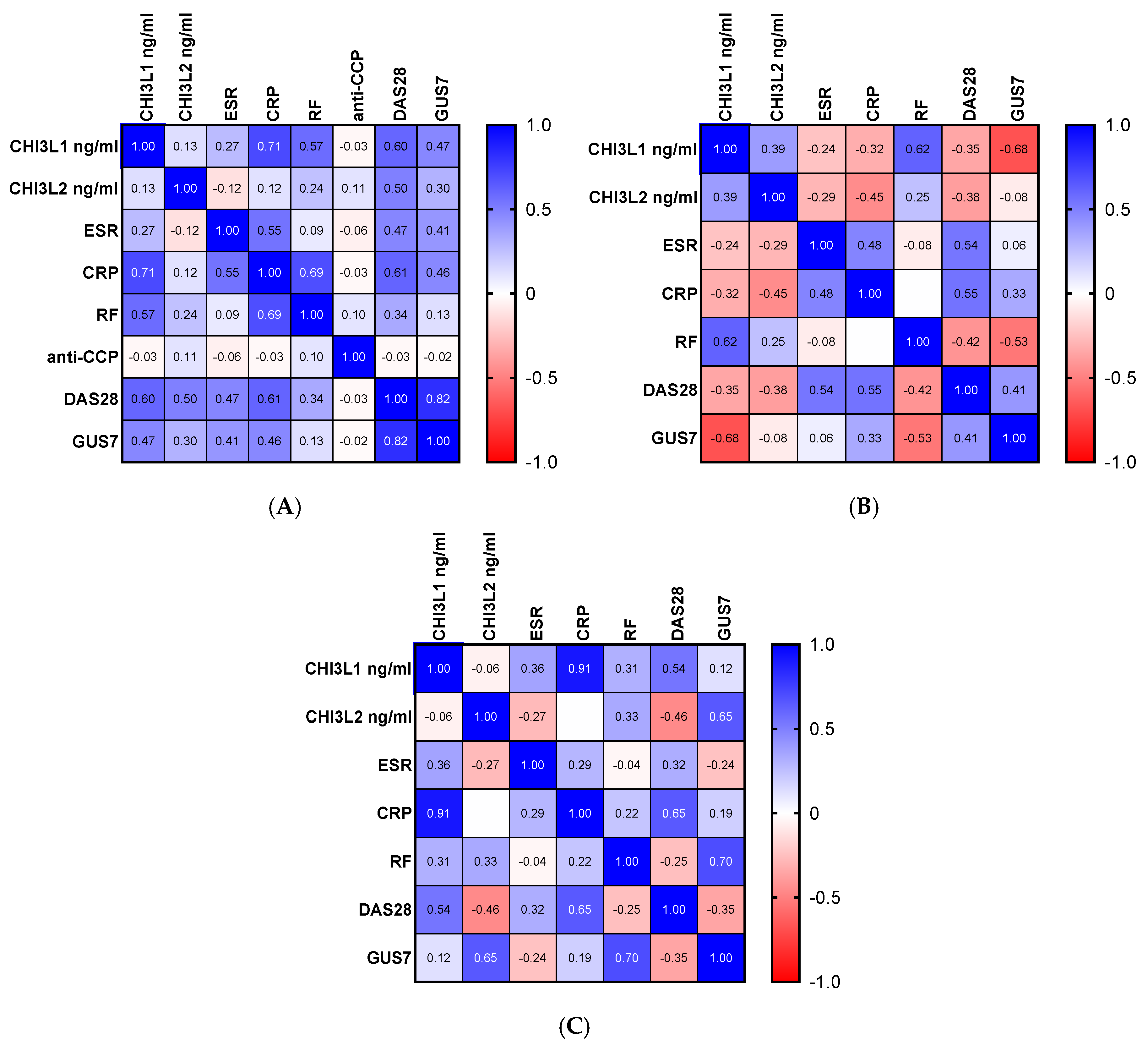

2.2. Correlation Between Chitinase-like Proteins, Ultrasonography Scores and Biochemical Markers

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients

4.2. Methods

4.3. Ultrasound Examination

4.4. qPCR Assessment of Gene CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 Expression

4.5. ELISA for Detection of Plasma Levels of CHI3L1 and CHI3L2

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diaz-Gonzalez, F.; Hernandez-Hernandez, M.V. Rheumatoid arthritis. Med. Clin. 2023, 161, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goeb, V.; Fardellone, P.; Sibilia, J.; Ponchel, F. Biomarkers in rheumatoid arthritis. Mediat. Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 379310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firestein, G.S.; McInnes, I.B. Immunopathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Immunity 2017, 46, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.M.; Weinblatt, M.E. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2001, 358, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Jiang, X.; Yang, Q. Glycoside hydrolase family 18 chitinases: The known and the unknown. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 43, 107553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renkema, G.H.; Boot, R.G.; Au, F.L.; Donker-Koopman, W.E.; Strijland, A.; Muijsers, A.O.; Hrebicek, M.; Aerts, J.M. Chitotriosidase, a chitinase, and the 39-kDa human cartilage glycoprotein, a chitin-binding lectin, are homologues of family 18 glycosyl hydrolases secreted by human macrophages. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998, 251, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, R.; Hamel, K.; Petersen, L.; Cao, Q.J.; Arenas, R.B.; Bigelow, C.; Bentley, B.; Yan, W. YKL-40, a secreted glycoprotein, promotes tumor angiogenesis. Oncogene 2009, 28, 4456–4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recklies, A.D.; White, C.; Ling, H. The chitinase 3-like protein human cartilage glycoprotein 39 (HC-gp39) stimulates proliferation of human connective-tissue cells and activates both extracellular signal-regulated kinase- and protein kinase B-mediated signalling pathways. Biochem. J. 2002, 365, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakova, M.; Batalov, A.; Deneva, T.; Mateva, N.; Kolarov, Z.; Sarafian, V. Relationship between sonographic parameters and YKL-40 levels in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol. Int. 2013, 33, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karalilova, R.; Kazakova, M.; Batalov, A.; Sarafian, V. Correlation between protein YKL-40 and ultrasonographic findings in active knee osteoarthritis. Med. Ultrason. 2018, 1, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, M.; Hasegawa, Y.; Kondo, S.; Iwata, H. Concentration and localization of YKL-40 in hip joint diseases. J. Rheumatol. 2001, 28, 341–345. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, L.D.; Smeds, J.; George, J.; Vega, V.B.; Vergara, L.; Ploner, A.; Pawitan, Y.; Hall, P.; Klaar, S.; Liu, E.T.; et al. An expression signature for p53 status in human breast cancer predicts mutation status, transcriptional effects, and patient survival. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 13550–13555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dichev, V.; Mehterov, N.; Kazakova, M.; Karalilova, R.; Batalov, A.; Sarafian, V. The lncRNAs/miR-30e/CHI3L1 Axis Is Dysregulated in Systemic Sclerosis. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyatake, K.; Tsuji, K.; Yamaga, M.; Yamada, J.; Matsukura, Y.; Abula, K.; Sekiya, I.; Muneta, T. Human YKL39 (chitinase 3-like protein 2), an osteoarthritis-associated gene, enhances proliferation and type II collagen expression in ATDC5 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 431, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conigliaro, P.; Triggianese, P.; De Martino, E.; Fonti, G.L.; Chimenti, M.S.; Sunzini, F.; Viola, A.; Canofari, C.; Perricone, R. Challenges in the treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2019, 18, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesha, S.H.; Dudics, S.; Acharya, B.; Moudgil, K.D. Cytokine-modulating strategies and newer cytokine targets for arthritis therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 16, 887–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaylova, V.; Kazakova, M.; Batalov, Z.; Karalilova, R.; Batalov, A.; Sarafian, V. JAK inhibitors improve ATP production and mitochondrial function in rheumatoid arthritis: A pilot study. Rheumatol. Int. 2024, 44, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, N.A.; Johansen, J.S. YKL-40-A Protein in the Field of Translational Medicine: A Role as a Biomarker in Cancer Patients? Cancers 2010, 2, 1453–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrozier, T.; Carlier, M.C.; Mathieu, P.; Colson, F.; Debard, A.L.; Richard, S.; Favret, H.; Bienvenu, J.; Vignon, E. Serum levels of YKL-40 and C reactive protein in patients with hip osteoarthritis and healthy subjects: A cross sectional study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2000, 59, 828–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Trinh, K.; Figueira, W.F.; Price, P.A. Isolation and sequence of a novel human chondrocyte protein related to mammalian members of the chitinase protein family. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 19415–19420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuruha, J.; Masuko-Hongo, K.; Kato, T.; Sakata, M.; Nakamura, H.; Sekine, T.; Takigawa, M.; Nishioka, K. Autoimmunity against YKL-39, a human cartilage derived protein, in patients with osteoarthritis. J. Rheumatol. 2002, 29, 1459–1466. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rusak, A.; Katnik, E.; Gornicki, T.; Schmuttermaier, C.; Kujawa, K.; Piotrowska, A.; Ratajczak-Wielgomas, K.; Kmiecik, A.; Wojnar, A.; Dziegiel, P.; et al. New insights into the role of the CHI3L2 protein in invasive ductal breast carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batalov, A.Z.; Kuzmanova, S.I.; Penev, D.P. Ultrasonographic evaluation of knee joint cartilage in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Folia Med. 2000, 42, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ponikowska, M.; Swierkot, J.; Nowak, B. The importance of ultrasound examination in early arthritis. Reumatologia 2018, 56, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steck, E.; Breit, S.; Breusch, S.J.; Axt, M.; Richter, W. Enhanced expression of the human chitinase 3-like 2 gene (YKL-39) but not chitinase 3-like 1 gene (YKL-40) in osteoarthritic cartilage. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 299, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoreschi, K.; Laurence, A.; O’Shea, J.J. Janus kinases in immune cell signaling. Immunol. Rev. 2009, 228, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.; Cohen, S. JAK Inhibitors: What Is New? Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2020, 22, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Hua, Z.; Luo, X.; Li, Y.; Yu, L.; Li, M.; Lu, C.; Zhao, T.; Liu, Y. Application and pharmacological mechanism of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 150, 113074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Song, D.; Xiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, W.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, X. Reactive oxygen species, not Ca2+, mediates methotrexate-induced autophagy and apoptosis in spermatocyte cell line. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2020, 126, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bykerk, V.P.; Massarotti, E.M. The new ACR/EULAR classification criteria for RA: How are the new criteria performing in the clinic? Rheumatology 2012, 51, vi10-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolen, J.S.; Landewe, R.B.M.; Bergstra, S.A.; Kerschbaumer, A.; Sepriano, A.; Aletaha, D.; Caporali, R.; Edwards, C.J.; Hyrich, K.L.; Pope, J.E.; et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2022 update. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 82, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevoo, M.L.; van’T Hof, M.A.; Kuper, H.H.; van Leeuwen, M.A.; van de Putte, L.B.; van Riel, P.L. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995, 38, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaylova, V.; Karalilova, R.; Batalov, Z.; Kazakova, M.; Batalov, A.; Sarafian, V. Inflammation, mitochondrial and lysosomal dysfunction as key players in rheumatoid arthritis? Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 141, 112919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruyn, G.A.; Iagnocco, A.; Naredo, E.; Balint, P.V.; Gutierrez, M.; Hammer, H.B.; Collado, P.; Filippou, G.; Schmidt, W.A.; Jousse-Joulin, S.; et al. OMERACT Definitions for Ultrasonographic Pathologies and Elementary Lesions of Rheumatic Disorders 15 Years On. J. Rheumatol. 2019, 46, 1388–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backhaus, M.; Ohrndorf, S.; Kellner, H.; Strunk, J.; Backhaus, T.M.; Hartung, W.; Sattler, H.; Albrecht, K.; Kaufmann, J.; Becker, K.; et al. Evaluation of a novel 7-joint ultrasound score in daily rheumatologic practice: A pilot project. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 61, 1194–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihaylova, V.; Batalov, Z.; Karalilova, R.; Batalov, A.; Kazakova, M.; Sarafian, V. A Pilot Study on Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Autophagy, and Inflammation in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients on Methotrexate Treatment. Orthop. Surg. Trauma 2025, 1, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Patients Before Therapy (n = 24) | Patients After Therapy with TOFA (n = 14) | Patients After Therapy with MTX (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRP mg/L, (normal range ≤ 6) | 20.45 ± 5.44 | 9.9 ± 3.6 | 10.17 ± 3.35 |

| RF IU/mL, (normal range < 10) | 172 ± 44.29 | 70 ± 11.5 | 87.18 ± 29 |

| ESR mm/h, (normal range 15–20) | 53.68 ± 4.11 | 27 ± 9 | 32.7 ± 4.9 |

| DAS28, remission (≤2.6) | 5.66 ± 0.2 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 3.9 ± 0.2 |

| GUS7, (0–108) | 26.5 ± 2.4 | 11 ± 1 | 14 ± 1.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kazakova, M.; Mihaylova, V.; Batalov, Z.; Karalilova, R.; Batalov, A.; Sarafian, V. Gene and Protein Profiles of CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010101

Kazakova M, Mihaylova V, Batalov Z, Karalilova R, Batalov A, Sarafian V. Gene and Protein Profiles of CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010101

Chicago/Turabian StyleKazakova, Maria, Valentina Mihaylova, Zguro Batalov, Rositsa Karalilova, Anastas Batalov, and Victoria Sarafian. 2026. "Gene and Protein Profiles of CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010101

APA StyleKazakova, M., Mihaylova, V., Batalov, Z., Karalilova, R., Batalov, A., & Sarafian, V. (2026). Gene and Protein Profiles of CHI3L1 and CHI3L2 in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010101