Transdiagnostic Efficacy of Cariprazine: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Efficacy Across Ten Symptom Domains

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Criteria

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Recorded Variables and Data Extraction

2.4. Outcome Measures

2.4.1. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

2.4.2. Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale

2.4.3. Young Mania Rating Scale

2.4.4. Negative Symptom Assessment-16

2.4.5. Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale

2.4.6. Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale

2.4.7. Functioning Assessment Short Test

2.4.8. Cognitive Drug Research Battery

2.4.9. Color Trail Test

2.5. Data Analyses

3. Results

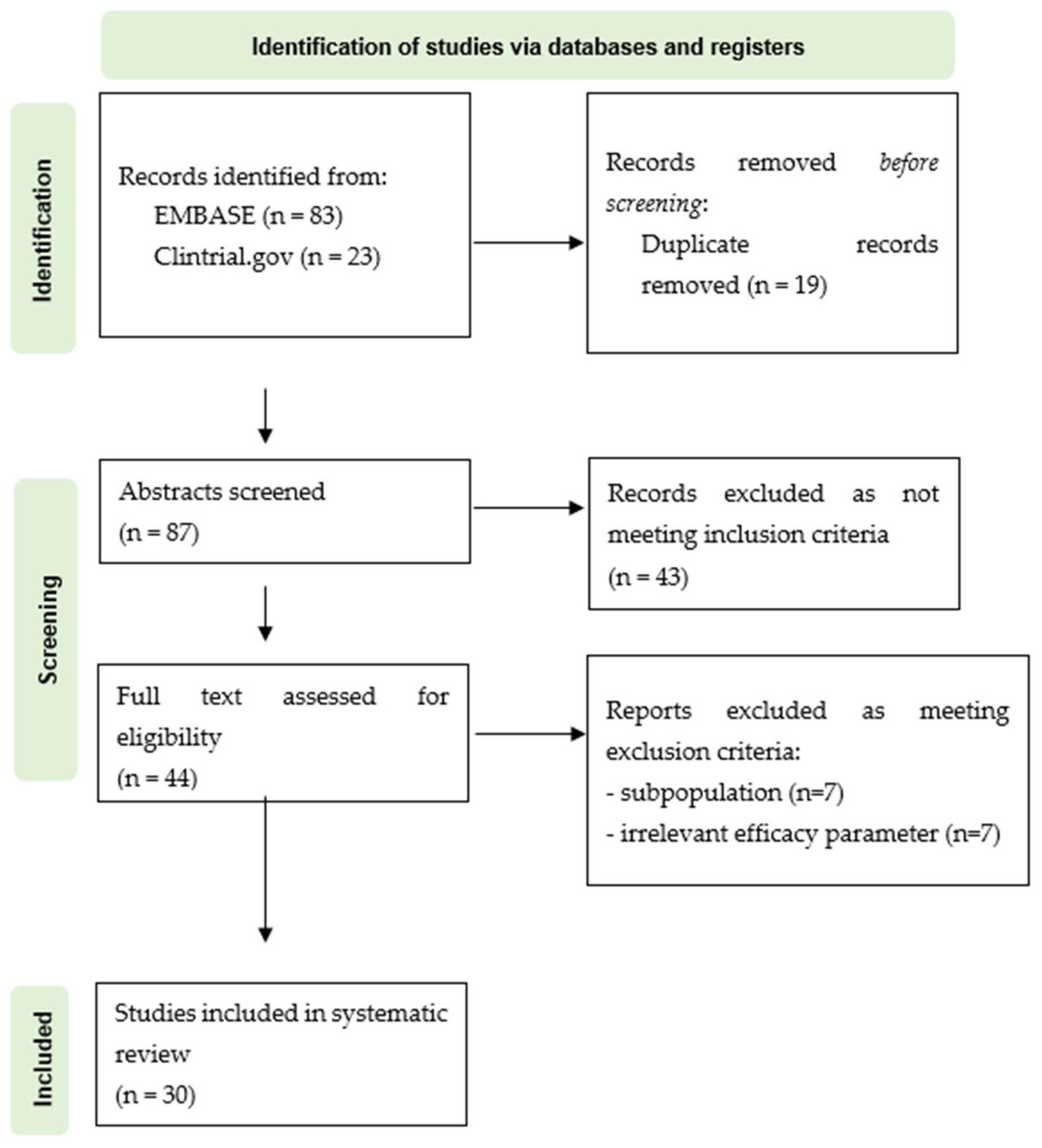

3.1. PRISMA Flowchart

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Patient Characteristics

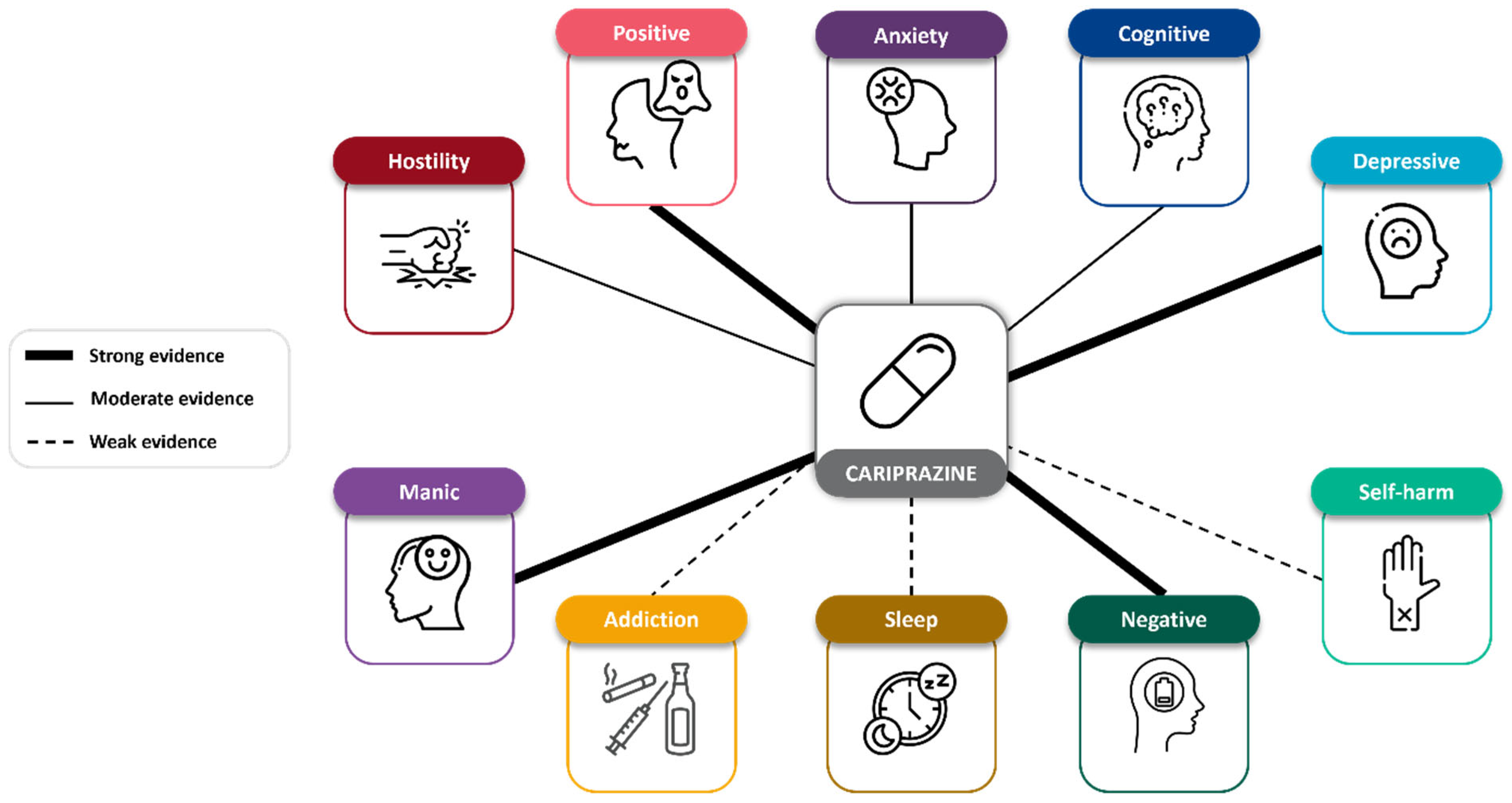

3.4. Efficacy on Transdiagnostic Symptoms

3.4.1. Positive Symptoms

3.4.2. Negative Symptoms

3.4.3. Cognitive Symptoms

3.4.4. Manic Symptoms

3.4.5. Depressive Symptoms

3.4.6. Addiction Symptoms

3.4.7. Sleep Symptoms

3.4.8. Anxiety Symptoms

3.4.9. Hostility Symptoms

3.4.10. Self-Harm Symptoms

4. Discussion

4.1. Positive, Manic, and Hostility Symptoms: The Role of Dopamine D2 Receptors

4.2. Negative, Cognitive, and Addiction Symptoms: The Role of Dopamine D3 Receptors

4.3. Depressive, Anxiety, and Self-Harm Symptoms: The Role of Serotonin 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A Receptors

4.4. Sleep Symptoms

4.5. Safety Considerations

4.6. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- The World Health Organisation. International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11) 11th Edition. 2019. Available online: https://icd.who.int/en/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Dalgleish, T.; Black, M.; Johnston, D.; Bevan, A. Transdiagnostic approaches to mental health problems: Current status and future directions. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 88, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusar-Poli, P.; Solmi, M.; Brondino, N.; Davies, C.; Chae, C.; Politi, P.; Borgwardt, S.; Lawrie, S.M.; Parnas, J.; McGuire, P. Transdiagnostic psychiatry: A systematic review. World Psychiatry 2019, 18, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansell, W. Transdiagnostic psychiatry goes above and beyond classification. World Psychiatry 2019, 18, 360–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Lee, D.; Baek, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Park, W.Y. Transdiagnostic clustering and network analysis for questionnaire-based symptom profiling and drug recommendation in the UK Biobank and a Korean cohort. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kist, J.D.; Vrijsen, J.N.; Mulders, P.C.R.; van Eijndhoven, P.F.P.; Tendolkar, I.; Collard, R.M. Transdiagnostic psychiatry: Symptom profiles and their direct and indirect relationship with well-being. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2023, 161, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leucht, S.; van Os, J.; Jäger, M.; Davis, J.M. Prioritization of psychopathological symptoms and clinical characterization in psychiatric diagnoses: A narrative review. JAMA Psychiatry 2024, 81, 1149–1158. Available online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/2823588 (accessed on 24 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Correll, C.U.; Dombi, Z.B.; Barabássy, Á.; Németh, G.; Brevig, T.; McIntyre, R.S. The Transdiagnostic Global Impression—Psychopathology scale (TGI-P): Initial development of a novel transdiagnostic tool for assessing, tracking, and visualising psychiatric symptom severity in everyday practice. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2024, 88, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMA 2017. Reagila smpc. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/reagila-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Kiss, B.; Horváth, A.; Némethy, Z.; Schmidt, É.; Laszlovszky, I.; Bugovics, G.; Fazekas, K.; Hornok, K.; Orosz, S.; Gyertyán, I.; et al. Cariprazine (RGH-188), a dopamine D3 receptor-preferring, D3/D2 dopamine receptor antagonist-partial agonist antipsychotic candidate: In vitro and neurochemical profile. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2010, 333, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabássy, Á.; Dombi, Z.B.; Németh, G. D3 Receptor-Targeted Cariprazine: Insights from Lab to Bedside. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, B.; Horti, F.; Bobok, A. Cariprazine, a D3/D2 dopamine receptor partial agonist antipsychotic, displays greater D3 receptor occupancy in vivo compared with other antipsychotics. Schizophr. Res. 2012, 136 (Suppl. 1), S190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, S.; Mamo, D. Half a century of antipsychotics and still a central role for dopamine D2 receptors. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 27, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, F.K.; Redfield Jamison, K. Manic-Depressive Illness: Bipolar Disorders and Recurrent Depression, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid, A.A.; Pettibone, J.R.; Mabrouk, O.S.; Hetrick, V.L.; Schmidt, R.; Vander Weele, C.M.; Kennedy, R.T.; Aragona, B.J.; Berke, J.D. Mesolimbic dopamine signals the value of work. Nat. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koob, G.; Caine, B.; Markou, A.; Pulvirenti, L.; Weiss, F. Role for the mesocortical dopamine system in the motivating effects of cocaine. NIDA Res. Monogr. 1994, 145, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Biesdorf, C.; Wang, A.L.; Topic, B.; Petri, D.; Milani, H.; Huston, J.; de Souza Silva, M.A. Dopamine in the nucleus accumbens core, but not shell, increases during signaled food reward and decreases during delayed extinction. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2015, 123, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Der-Avakian, A.; Markou, A. The Neurobiology of Anhedonia and Other Reward-Related Deficits. Trends Neurosci. 2012, 35, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggio, G.M.; Salomone, S.; Bucolo, C.; Platania, C.; Micale, V.; Caraci, F.; Drago, F. Dopamine D3 receptor as a new pharmacological target for the treatment of depression. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 719, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cools, R.; D’Esposito, M. Inverted-U-shaped dopamine actions on human working memory and cognitive control. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 69, e113–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, S.M. Describing an Atypical Antipsychotic: Receptor Binding and Its Role in Pathophysiology. Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry 2003, 5, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bardin, L.; Auclair, A.L.; Kleven, M.S.; Prinssen, E.P. Effects of 5-HT1A receptor agonists and antagonists in rat models of anxiety. Psychopharmacology 2007, 190, 497–508. [Google Scholar]

- Yohn, C.N.; Gergues, M.M.; Samuels, B.A. The role of 5-HT receptors in depression. Mol. Brain 2017, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millan, M.J. Serotonin 5-HT2C receptors as a target for the treatment of depressive and anxious states: Focus on novel therapeutic strategies. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2005, 1, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Altman, D.; Antes, G.; Atkins, D.; Barbour, V.; Barrowman, N.; Berlin, J.A.; et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, S.R.; Fiszbein, A.; Opler, L.A. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1987, 13, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marder, S.R.; Davis, J.M.; Chouinard, G. The effects of risperidone on the five dimensions of schizophrenia derived by factor analysis: Combined results of the North American trials. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1997, 58, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, S.A.; Asberg, M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br. J. Psychiatry 1979, 134, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.C.; Biggs, J.T.; Ziegler, V.E.; Meyer, D.A. A rating scale for mania: Reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br. J. Psychiatry 1978, 133, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 1959, 32, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, K.; Brown, G.K.; Stanley, B.; Brent, D.A.; Yershova, K.V.; Oquendo, M.A.; Currier, G.W.; Melvin, G.A.; Greenhill, L.; Shen, S.; et al. The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial Validity and Internal Consistency Findings from Three Multisite Studies with Adolescents and Adults. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011, 168, 1266–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.R.; Sánchez-Moreno, J.; Martínez-Aran, A.; Salamero, M.; Torrent, C.; Reinares, M.; Comes, M.; Colom, F.; Riel, W.V.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; et al. Validity and reliability of the Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST) in bipolar disorder. Clin. Pract. Epidemol. Ment. Health 2007, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, P.M.; Surmon, D.J.; Wesnes, K.A.; Wilcock, G.K. The cognitive drug research computerized assessment system for demented patients: A validation study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 1991, 6, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durgam, S.; Litman, R.E.; Papadakis, K.; Li, D.; Németh, G.; Laszlovszky, I. Cariprazine in the treatment of schizophrenia: A proof-of-concept trial. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 31, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durgam, S.; Cutler, A.J.; Lu, K.; Migliore, R.; Ruth, A.; Laszlovszky, I.; Németh, G.; Meltzer, H.Y. Cariprazine in acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: A fixed-dose, phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2015, 76, e1574–e1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, J.M.; Zukin, S.; Wang, Y.; Lu, K.; Ruth, A.; Nagy, K.; Laszlovszky, I.; Durgam, S. Efficacy and Safety of Cariprazine in Acute Exacerbation of Schizophrenia: Results from an International, Phase III Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2015, 35, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durgam, S.; Starace, A.; Li, D.; Migliore, R.; Ruth, A.; Németh, G.; Laszlovszky, I. An evaluation of the safety and efficacy of cariprazine in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: A phase II, randomized clinical trial. Schizophr. Res. 2014, 152, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durgam, S.; Earley, W.; Li, R.; Li, D.; Lu, K.; Laszlovszky, I.; Fleischhacker, W.W.; Nasrallah, H.A. Long-term cariprazine treatment for the prevention of relapse in patients with schizophrenia: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Schizophr. Res. 2016, 176, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, G.; Laszlovszky, I.; Czobor, P.; Szalai, E.; Szatmári, B.; Harsányi, J.; Barabássy, Á.; Debelle, M.; Durgam, S.; Bitter, I. Cariprazine versus risperidone monotherapy for treatment of predominant negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia: A randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durgam, S.; Starace, A.; Li, D.; Migliore, R.; Ruth, A.; Németh, G.; Laszlovszky, I. The efficacy and tolerability of cariprazine in acute mania associated with bipolar I disorder: A phase II trial. Bipolar Disord. 2015, 17, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, G.S.; Greenberg, W.M.; Starace, A.; Lu, K.; Ruth, A.; Laszlovszky, I.; Németh, G.; Durgam, S. Cariprazine in the treatment of acute mania in bipolar I disorder: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, Phase III trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 174, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, J.R.; Keck, P.E.; Starace, A.; Lu, K.; Ruth, A.; Laszlovszky, I.; Nemeth, G.; Durgam, S. Efficacy and safety of low- and high-dose Cariprazine in acute and mixed mania associated with bipolar I disorder: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2015, 76, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatham, L.N.; Vieta, E.; Earley, W. Evaluation of cariprazine in the treatment of bipolar I and II depression: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 35, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earley, W.R.; Burgess, M.V.; Khan, B.; Rekeda, L.; Suppes, T.; Tohen, M.; Calabrese, J.R. Efficacy and safety of cariprazine in bipolar I depression: A double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Bipolar Disord. 2020, 22, 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earley, W.; Burgess, M.V.; Rekeda, L.; Dickinson, R.; Szatmári, B.; Németh, G.; McIntyre, R.S.; Sachs, G.S.; Yatham, L.N. Cariprazine treatment of bipolar depression: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2019, 176, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durgam, S.; Earley, W.; Lipschitz, A.; Guo, H.; Laszlovszky, I.; Németh, G.; Vieta, E.; Calabrese, J.R.; Yatham, L.N. An 8-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled evaluation of the safety and efficacy of cariprazine in patients with bipolar I depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2016, 173, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntyre, R.S.; Davis, B.; Rodgers, J.; Rekeda, L.; Adams, J.; Yatham, L.N. Cariprazine as a maintenance therapy in the prevention of mood episodes in adults with bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2024, 26, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fava, M.; Durgam, S.; Earley, W.; Lu, K.; Hayes, R.; Laszlovszky, I.; Németh, G. Efficacy of adjunctive low-dose cariprazine in major depressive disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 33, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earley, W.R.; Guo, H.; Németh, G.; Harsányi, J.; Thase, M.E. Cariprazine Augmentation to Antidepressant Therapy in Major Depressive Disorder: Results of a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 2018, 48, 62–80. [Google Scholar]

- Durgam, S.; Earley, W.; Guo, H.; Li, D.; Németh, G.; Laszlovszky, I.; Fava, M.; Montgomery, S.A. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive cariprazine in inadequate responders to antidepressants: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in adult patients with major depressive disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2016, 77, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, G.S.; Yeung, P.P.; Rekeda, L.; Khan, A.; Adams, J.L.; Fava, M. Adjunctive Cariprazine for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase 3 Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2023, 180, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riesenberg, R.; Yeung, P.P.; Rekeda, L.; Sachs, G.S.; Kerolous, M.; Fava, M. Cariprazine for the Adjunctive Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder in Patients With Inadequate Response to Antidepressant Therapy: Results of a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2023, 84, 22m14643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marder, S.; Fleischhacker, W.W.; Earley, W.; Lu, K.; Zhong, Y.; Németh, G.; Laszlovszky, I.; Szalai, E.; Durgam, S. Efficacy of cariprazine across symptom domains in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: Pooled analyses from 3 phase II/III studies. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019, 29, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citrome, L.; Durgam, S.; Lu, K.; Ferguson, P.; Laszlovszky, I. The effect of Cariprazine on hostility associated with schizophrenia: Post hoc analyses from 3 randomized controlled trials. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2016, 77, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earley, W.; Guo, H.; Daniel, D.; Nasrallah, H.; Durgam, S.; Zhong, Y.; Patel, M.; Barabássy, Á.; Szatmári, B.; Németh, G. Efficacy of cariprazine on negative symptoms in patients with acute schizophrenia: A post hoc analysis of pooled data. Schizophr. Res. 2019, 204, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleischhacker, W.; Galderisi, S.; Laszlovszky, I.; Szatmári, B.; Barabássy, Á.; Acsai, K.; Szalai, E.; Harsányi, J.; Earley, W.; Patel, M. The efficacy of cariprazine in negative symptoms of schizophrenia: Post hoc analyses of PANSS individual items and PANSS-derived factors. Eur. Psychiatry 2019, 58, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citrome, L.; Li, C.; Yu, J.; Kramer, K.; Nguyen, H.B. Effects of cariprazine on reducing symptoms of irritability, hostility, and agitation in patients with manic or mixed episodes of bipolar I disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 358, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieta, E.; Durgam, S.; Lu, K.; Ruth, A.; Debelle, M.; Zukin, S. Effect of cariprazine across the symptoms of mania in bipolar I disorder: Analyses of pooled data from phase II/III trials. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015, 25, 1882–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatham, L.N.; Vieta, E.; McIntyre, R.S.; Jain, R.; Patel, M.; Earley, W. Broad Efficacy of Cariprazine on Depressive Symptoms in Bipolar Disorder and the Clinical Implications. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2020, 22, 20m02611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; McIntyre, R.S.; Cutler, A.J.; Earley, W.R.; Nguyen, H.B.; Adams, J.L.; Yatham, L.N. Efficacy of cariprazine in patients with bipolar depression and higher or lower levels of baseline anxiety: A pooled post hoc analysis. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2024, 39, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieta, E.; McIntyre, R.S.; Yu, J.; Aronin, L.C.; Kramer, K.; Nguyen, H.B. Full-spectrum efficacy of cariprazine across manic and depressive symptoms of bipolar I disorder in patients experiencing mood episodes: Post hoc analysis of pooled randomized controlled trial data. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 366, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citrome, L.; Reda, I.; Kerolous, M. Adjunctive cariprazine for the treatment of major depressive disorder: Number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 369, 1238–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, R.S.; Daniel, D.G.; Vieta, E.; Laszlovszky, I.; Goetghebeur, P.J.; Earley, W.R.; Patel, M. The efficacy of cariprazine on cognition: A post hoc analysis from phase II/III clinical trials in bipolar mania, bipolar depression, and schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. 2023, 28, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earley, W.; Durgam, S.; Lu, K.; Debelle, M.; Laszlovszky, I.; Vieta, E.; Yatham, L.N. Tolerability of cariprazine in the treatment of acute bipolar I mania: A pooled post hoc analysis of 3 phase II/III studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 215, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boland, R.; Verduin, M. Kaplan and Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 11th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Citrome, L. The ABC’s of dopamine receptor partial agonists—Aripiprazole, brexpiprazole and cariprazine: The 15-min challenge to sort these agents out. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2015, 69, 1211–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huhn, M.; Nikolakopoulou, A.; Schneider-Thoma, J.; Krause, M.; Samara, M.; Peter, N.; Arndt, T.; Bäckers, L.; Rothe, P.; Cipriani, A.; et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 32 oral antipsychotics for the acute treatment of adults with multi-episode schizophrenia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2019, 349, 934–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmassi, C.; Dell’Oste, V.; Fantasia, S.; Bordacchini, A.; Bertelloni, C.A.; Scarpellini, P.; Pedrinelli, V. A 12-month longitudinal naturalistic follow-up of cariprazine in schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1382013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, S.; Kalniunas, A.; Sharma, H.; Raza-Syed, A.; Kamal, M.; Larkin, F. Efficacy and safety of cariprazine augmentation in patients treated with clozapine: A pilot study. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 12, 20451253221132087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, S.H.; Clayton, P.J. The Medical Basis of Psychiatry; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, S.M. Drugs for psychosis and mood: Unique actions at D3, D2, and D1 dopamine receptor subtypes. CNS Spectr. 2017, 22, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, M.; Zhu, Y.; Huhn, M.; Schneider-Thoma, J.; Bighelli, I.; Nikolakopoulou, A.; Leucht, S. Antipsychotic drugs for patients with schizophrenia and predominant or prominent negative symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 268, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rancans, E.; Dombi, Z.B.; Matrai, P.; Barabassy, A.; Sebe, B.; Skrivele, I.; Nemeth, G. The effectiveness and safety of cariprazine in schizophrenia patients with negative symptoms and insufficient effectiveness of previous antipsychotic therapy: An observational study. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 36, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragasek, J.; Dombi, Z.B.; Acsai, K.; Dzurilla, V.; Barabássy, Á. The management of patients with predominant negative symptoms in Slovakia: A 1-year longitudinal, prospective, multicentric cohort study. Eur. Psychiatry 2024, 67, e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, S.; Kalniunas, A.; Maret, J. Cariprazine for negative symptoms in early psychosis: A pilot study with a 6-month follow-up. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1183912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szerman, N.; Vega, P.; Roncero, C.; Peris, L.; Grau-López, L.; Basurte-Villamor, I. Cariprazine as a maintenance treatment in dual schizophrenia: A 6-month observational study in patients with schizophrenia and cannabis use. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2024, 40, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez Cruz, J.; Sahlsten Schölin, J.; Hjorth, S. Case Report: Cariprazine in a Patient With Schizophrenia, Substance Abuse, and Cognitive Dysfunction. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 727666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montes, J.M.; Montes, P.; Hernández-Huerta, D. Cariprazine in three acute patients with schizophrenia: A real-world experience. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2021, 17, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, A.; Marini, S.; Matarazzo, I.; De Berardis, D.; Ventriglio, A. Cariprazine in the treatment of psychosis with comorbid cannabis use: A case report. Psychiatry Res. Commun. 2022, 2, 100048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmassi, C.; Dell’Oste, V.; Bertelloni, C.A.; Diadema, E.; Avella, M.T.; Simoncini, M.; Dell’Osso, L. Clinical Experiences with Cariprazine in Schizophrenic Patients with Comorbid Substance Abuse. Evid.-Based Psychiatr. Care 2019, 5 (Suppl. 3), 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Di Sciascio, G.; Palumbo, C. Experiences of Switching to Cariprazine. Evid.-Based Psychiatr. Care 2019, 5 (Suppl. 3), 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Halaris, A.; Wuest, J. Metabolic syndrome reversal with cariprazine. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 39, 413–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.T.; Li, B. Case Series: Cariprazine for treatment of methamphetamine use disorder. Am. J. Addict. 2022, 31, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, V.; Di Salvo, G.; Maina, G. Remission of persistent methamphetamine-induced psychosis after cariprazine therapy: Presentation of a case report. J. Addict. Dis. 2021, 40, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, R.A.; Hastings, C.; Della-Pietra, U.; Singh, C.; Jacome, M. A Case Report of Treatment With Cariprazine in a Recurrent Psychosis Presumably Induced by Methamphetamine. Cureus 2023, 15, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannucchi, T.; Taddeucci, C.; Tatini, L. Case Report: Functional and Symptomatic Improvement With Cariprazine in Various Psychiatric Patients: A Case Series. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 878889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, L.O.; Miller, J.J. Cariprazine May Decrease Substance Abuse in Patients with Bipolar I Disorder. Psychiatric Times 2019, 36. Available online: https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/cariprazine-may-decrease-substance-abuse-patients-bipolar-i-disorder (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Martinotti, G.; Chiappini, S.; Mosca, A.; Miuli, A.; Santovito, M.C.; Pettorruso, M.; Skryabin, V.; Sensi, S.L.; Giannantonio, M.D. Atypical Antipsychotic Drugs in Dual Disorders: Current Evidence for Clinical Practice. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2022, 28, 2241–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, F.; Cheng, Z.; Piao, J.; Cui, R.; Li, B. Dopamine Receptors: Is It Possible to Become a Therapeutic Target for Depression? Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 947785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furczyk, K.; Schutová, B.; Michel, T.M.; Thome, J.; Büttner, A. The neurobiology of suicide—A Review of post-mortem studies. J. Mol. Psychiatry 2013, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, B.; Laszlovszky, I.; Krámos, B.; Visegrády, A.; Bobok, A.; Lévay, G.; Lendvai, B.; Román, V. Neuronal Dopamine D3 Receptors: Translational Implications for Preclinical Research and CNS Disorders. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fava, M.; Masand, P.S.; Maletic, V.; Chen, C.; Adams, J.L.; Kerolous, M. Efficacy of Adjunctive Cariprazine on Anxiety Symptoms in Patients With Major Depressive Disorder: Post Hoc Analysis of a Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2025, 86, 24m15506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, R.S.; Parikh, M.; Ta, J.; Waraich, S.; Cohen-Stavi, C.; Marci, C.; Nabulsi, N. Real-world effectiveness of cariprazine in major depressive disorder and bipolar I disorder in the United States. J. Med. Econ. 2025, 28, 885–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Sol Calderon, P.; Izquierdo de la Puente, A.; Fernández Fernández, R.; García Moreno, M. Use of cariprazine as an impulsivity regulator in an adolescent with non suicidal self-injury and suicidal attempts. Case report. Eur. Psychiatry 2023, 66, S739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, J.M.; Monti, D. The involvement of dopamine in the modulation of sleep and waking. Sleep Med. Rev. 2007, 11, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieda, M.; Sakurai, T. Orexin (Hypocretin) Receptor Agonists and Antagonists for Treatment of Sleep Disorders. CNS Drugs 2013, 27, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porkka-Heiskanen, T.; Strecker, R.E.; Thakkar, M.; Bjorkum, A.A.; Greene, R.W.M.R.W. Adenosine: A Mediator of the Sleep-Inducing Effects of Prolonged Wakefulness Tarja. Science 1997, 23, 1265–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huedo-Medina, T.B.; Kirsch, I.; Middlemass, J.; Klonizakis, M.; Siriwardena, A.N. Effectiveness of non-benzodiazepine hypnotics in treatment of adult insomnia: Meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration. BMJ 2012, 345, e8343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barabássy, Á.; Sebe, B.; Acsai, K.; Laszlovszky, I.; Szatmári, B.; Earley, W.R.; Németh, G. Safety and tolerability of cariprazine in patients with schizophrenia: A pooled analysis of eight phase II/III studies. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2021, 17, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valencia Carlo, Y.E.; Saracco-Alvarez, R.A.; Valencia Carlo, V.A.; Vázquez Vega, D.; Natera Rey, G.; Escamilla Orozco, R.I. Adverse effects of antipsychotics on sleep in patients with schizophrenia. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1189768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketter, T.A.; Sachs, G.S.; Durgam, S.; Lu, K.; Starace, A.; Laszlovszky, I.; Németh, G. The safety and tolerability of cariprazine in patients with manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder: A 16-week open-label study. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 225, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalniunas, A.; Chakrabarti, I.; Mandalia, R.; Munjiza, J.; Pappa, S. The Relationship Between Antipsychotic-Induced Akathisia and Suicidal Behaviour: A Systematic Review. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2021, 17, 3489–3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| disorders | Bipolar Depression | Bipolar Mania | Major Depression | Schizophrenia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| symptoms | |||||

| Positive | - | YMRS Item 8: content PANSS Total | - | PANSS FSPS | |

| Negative | - | - | - | PANSS-FSNS NSA-16 | |

| Cognitive | MADRS Item 6: concentration difficulties FAST cognition | YMRS Item 7: language-thought disorder PANSS-disorganized factor score | - | PANSS-disorganized factor score CDR CTT | |

| Depressive | MADRS Total Score | - | MADRS Total Score | PANSS anxiety/depression Factor score Depression (G6) | |

| Mania | - | YMRS Total Score | - | - | |

| Addiction | - | - | - | - | |

| Anxiety | MADRS Item 3: inner tension HAMA | - | HAMA | PANSS anxiety/depression Factor score Anxiety (G2) | |

| Sleep | MADRS Item 4: reduced sleep | YMRS Item 4: sleep | - | - | |

| Hostility | - | YMRS Item 5: irritability, item YMRS Item 9: disruptive-aggressive behavior | - | PANSS hostility factor score Hostility item (P7) | |

| Self-harm | MADRS Item 10: suicidal thoughts C-SSRS | C-SSRS | C-SSRS | C-SSRS | |

| Factor Score for Negative Symptoms (FSNS) | Factor Score for Positive Symptoms (FSPS) | Factor Score for Disorganized Thought | Factor Score for Uncontrolled Hostility/Excitement | Factor Score for Anxiety/Depression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | Blunted affect | P1 | Delusions | N5 | Difficulty in abstract thinking | G14 | Poor impulse control | G2 | Anxiety |

| N2 | Emotional withdrawal | P3 | Hallucinatory behavior | G5 | Mannerisms and posturing | P4 | Excitement | G3 | Guilt feelings |

| N3 | Poor rapport | P5 | Grandiosity | G10 | Disorientation | P7 | Hostility | G4 | Tension |

| N4 | Passive social withdrawal | P6 | Suspiciousness | G11 | Poor attention | G8 | Uncooperative-ness | G6 | Depression |

| N6 | Lack of spontaneity | N7 | Stereotyped thinking | G13 | Disturbance of volition | ||||

| G7 | Motor retardation | G1 | Somatic concern | G15 | Preoccupation | ||||

| G16 | Active social avoidance | G9 | Unusual thought content | P2 | Conceptual disorientation | ||||

| G12 | Lack of judgement | ||||||||

| Author, Year, Internal Code Reference | Design | Title | Indication | Transdiagnostic Symptom * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Durgam, 2016 (MD-03) [35] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 6-week study | Cariprazine in the treatment of schizophrenia: A proof-of-concept trial | Schizophrenia | Positive Negative |

| 2 | Durgam, 2015 (MD-04) [36] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 6-week study | Cariprazine in acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: A fixed-dose, phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled trial | Schizophrenia | Positive Negative Cognitive Self-harm Depressive Anxiety Hostility |

| 3 | Kane, 2015 (MD-05) [37] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 6-week study | Efficacy and safety of cariprazine in acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: Results from an international, phase III clinical trial | Schizophrenia | Positive Negative Cognitive Self-harm Depressive Anxiety Hostility |

| 4 | Durgam, 2014 (MD-16) [38] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 6-week study | An evaluation of the safety and efficacy of cariprazine in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: A phase II, randomized clinical trial | Schizophrenia | Positive Negative Cognitive Depressive Anxiety Hostility |

| 5 | Durgam, 2016 (MD-06) [39] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, up to 92-week study | Long-term cariprazine treatment for the prevention of relapse in patients with schizophrenia: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Schizophrenia | Positive Negative Self-harm |

| 6 | Németh, 2017 (005) [40] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, active-controlled, 26-week study in negative symptoms | Cariprazine as monotherapy for the treatment of predominant negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia: A randomized, double-blind, active-comparator controlled trial | Schizophrenia | Negative Cognitive Self-harm |

| 7 | Durgam, 2015 (MD-31) [41] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 3-week study | The efficacy and tolerability of cariprazine in acute mania associated with bipolar I disorder: a phase II trial | Bipolar Mania | Manic Positive Cognitive Hostility Sleep |

| 8 | Sachs, 2015 (MD-32) [42] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 3-week study | Cariprazine in the treatment of acute mania in bipolar I disorder: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial | Bipolar Mania | Manic Self-harm Positive Cognitive Hostility Sleep |

| 9 | Calabrese, 2015 (MD-33) [43] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 3-week study | Efficacy and safety of low- and high-dose cariprazine in patients with acute and mixed mania associated with bipolar I disorder | Bipolar Mania | Manic Positive Cognitive Hostility Sleep Self-harm |

| 10 | Yatham, 2020 (MD-52) [44] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 8-week study | Evaluation of cariprazine in the treatment of bipolar I and II depression: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial | Bipolar Depression | Depressive Self-harm |

| 11 | Earley, 2020 (MD-53) [45] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 6-week study | Efficacy and safety of cariprazine in bipolar I depression: A double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study | Bipolar Depression | Depressive Self-harm Anxiety Sleep Cognitive |

| 12 | Earley, 2019 (MD-54) [46] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 6-week study | Cariprazine treatment of bipolar depression: A randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study | Bipolar Depression | Depressive Self-harm Anxiety Sleep Cognitive |

| 13 | Durgam, 2016 (MD-56) [47] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 8-week study | An 8-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled evaluation of the safety and efficacy of cariprazine in patients with bipolar I depression | Bipolar Depression | Cognitive Depressive Anxiety Sleep Self-harm |

| 14 | McIntyre, 2024 (MD-25) [48] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled up to 39 weeks study | Cariprazine as a maintenance therapy in the prevention of mood episodes in adults with bipolar I disorder | Bipolar Disorder both episodes | Depressive Manic Self-harm |

| 15 | Fava, 2018 MD-71 [49] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 8-week study | Efficacy of adjunctive low-dose cariprazine in major depressive disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Major Depression | Depressive Self-harm |

| 16 | Earley, 2018 MD-72 [50] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 8-week study | Cariprazine augmentation to antidepressant therapy in major depressive disorder: Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Major Depression | Depressive Self-harm |

| 17 | Durgam, 2016 (MD-75) [51] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 8-week study | Efficacy and safety of adjunctive cariprazine in inadequate responders to antidepressants: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in adult MDD patients | Major Depression | Depressive Self-harm |

| 18 | Sachs, 2023 (3111-301-001) [52] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 6-week study | Adjunctive cariprazine for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study | Major Depression | Depressive Anxiety Self-harm |

| 19 | Riesenberg, 2023 (3111-302-001) [53] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 6-week study | Cariprazine for the adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorder in patients with inadequate response to antidepressant therapy: Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study | Major Depression | Depressive Anxiety Self-harm |

| 20 | Marder, 2019 [54] | Pooled post hoc of 3 RCT | Efficacy of cariprazine across symptom domains in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: Pooled analyses from 3 phase II/III studies | Schizophrenia | Positive Negative Cognitive Depressive Anxiety Hostility |

| 21 | Citrome, 2016 [55] | Pooled post hoc of 3 RCT | The effect of cariprazine on hostility associated with schizophrenia: Post hoc analyses from 3 randomized controlled trials | Schizophrenia | Hostility |

| 22 | Earley, 2019 [56] | Pooled post hoc of 3 RCT | Efficacy of cariprazine on negative symptoms in patients with acute schizophrenia: A post hoc analysis of pooled data | Schizophrenia | Negative |

| 23 | Fleischhacker, 2019 [57] | Post hoc of the 005 study | The efficacy of cariprazine in negative symptoms of schizophrenia: Post hoc analyses of PANSS individual items and PANSS-derived factors | Schizophrenia | Negative Positive Depressive Cognitive Anxiety Hostility |

| 24 | Citrome, 2024 [58] | Post hoc of 3 RCT | Effects of cariprazine on reducing symptoms of irritability, hostility, and agitation in patients with manic or mixed episodes of bipolar I disorder | Bipolar mania | Hostility |

| 25 | Vieta, 2015 [59] | Post hoc of 3 RCT | Effect of cariprazine across the symptoms of mania in bipolar I disorder: Analyses of pooled data from phase II/III trials | Bipolar mania | Manic Positive Cognitive Sleep Hostility |

| 26 | Yatham, 2020 [60] | Pooled post hoc of 3 RCT | Broad efficacy of cariprazine on depressive symptoms in bipolar disorder and the clinical implications | Bipolar Depression | Depressive Cognitive Anxiety Sleep Self-harm |

| 27 | Jain, 2024 [61] | Pooled post hoc of 2 RCT | Efficacy of cariprazine in patients with bipolar depression and higher or lower levels of baseline anxiety: a pooled post hoc analysis | Bipolar Depression | Anxiety |

| 28 | Vieta, 2024 [62] | Pooled post hoc of 6 RCT | Full-spectrum efficacy of cariprazine across manic and depressive symptoms of bipolar I disorder in patients experiencing mood episodes: Post hoc analysis of pooled randomized controlled trial data | Bipolar Disorder both episodes | Depressive Manic |

| 29 | Citrome, 2024 [63] | Pooled post hoc of 5 RCT | Adjunctive cariprazine for the treatment of major depressive disorder: Number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed | Major Depression | Depressive |

| 30 | McIntyre, 2023 [64] | Pooled post hoc in all indications | The efficacy of cariprazine on cognition: a post hoc analysis from phase II/III clinical trials in bipolar mania, bipolar depression, and schizophrenia | Bipolar Disorder both episodes, Schizophrenia | Cognitive |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barabassy, A.; Csehi, R.; Dombi, Z.B.; Szatmári, B.; Brevig, T.; Németh, G. Transdiagnostic Efficacy of Cariprazine: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Efficacy Across Ten Symptom Domains. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 995. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18070995

Barabassy A, Csehi R, Dombi ZB, Szatmári B, Brevig T, Németh G. Transdiagnostic Efficacy of Cariprazine: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Efficacy Across Ten Symptom Domains. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(7):995. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18070995

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarabassy, Agota, Réka Csehi, Zsófia Borbála Dombi, Balázs Szatmári, Thomas Brevig, and György Németh. 2025. "Transdiagnostic Efficacy of Cariprazine: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Efficacy Across Ten Symptom Domains" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 7: 995. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18070995

APA StyleBarabassy, A., Csehi, R., Dombi, Z. B., Szatmári, B., Brevig, T., & Németh, G. (2025). Transdiagnostic Efficacy of Cariprazine: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Efficacy Across Ten Symptom Domains. Pharmaceuticals, 18(7), 995. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18070995