Efficacy and Safety of Isatuximab, Carfilzomib, and Dexamethasone (IsaKd) in Multiple Myeloma Patients at the First Relapse After Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation and Lenalidomide Maintenance: Results from the Multicenter, Real-Life AENEID Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Patients

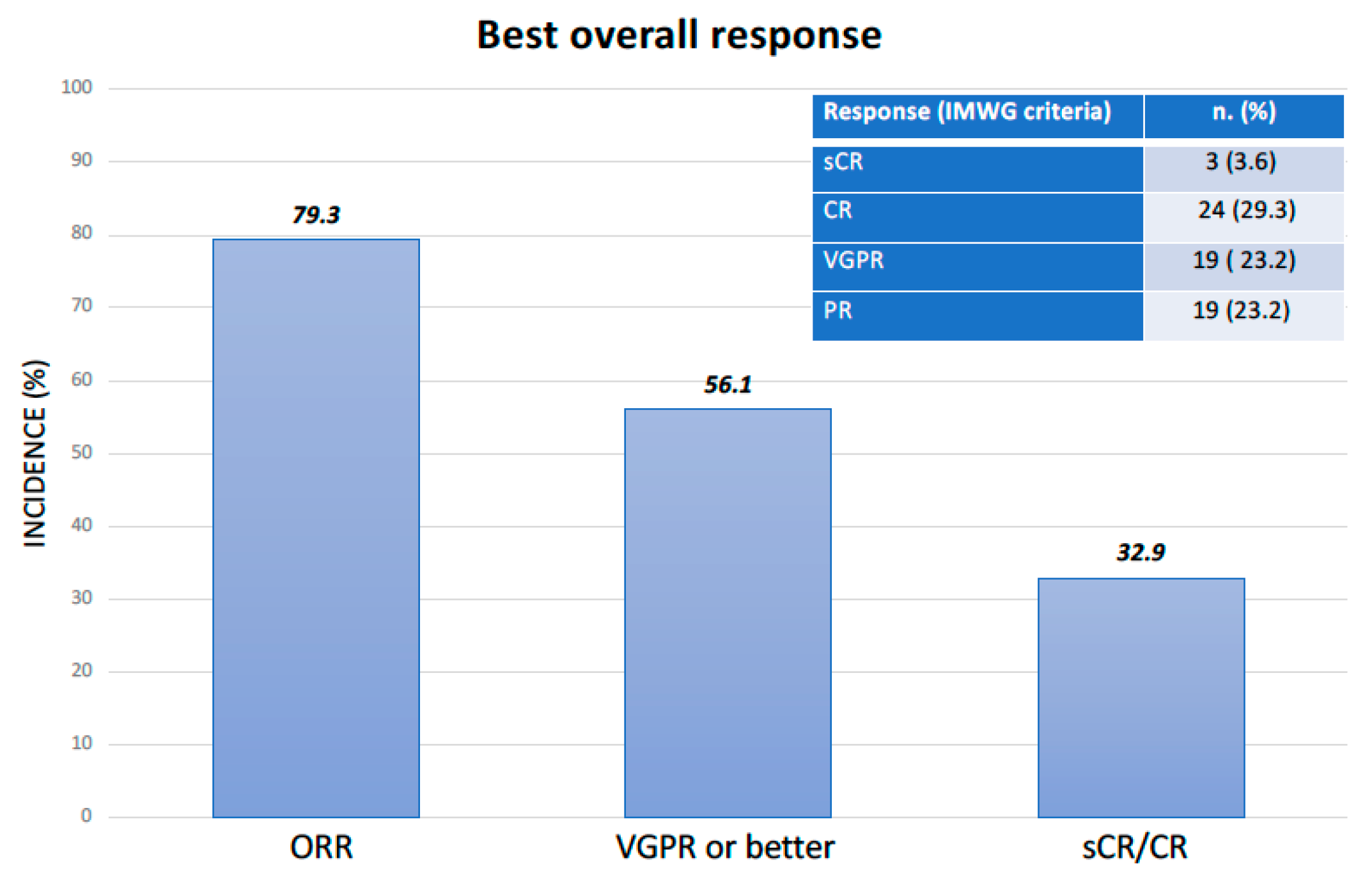

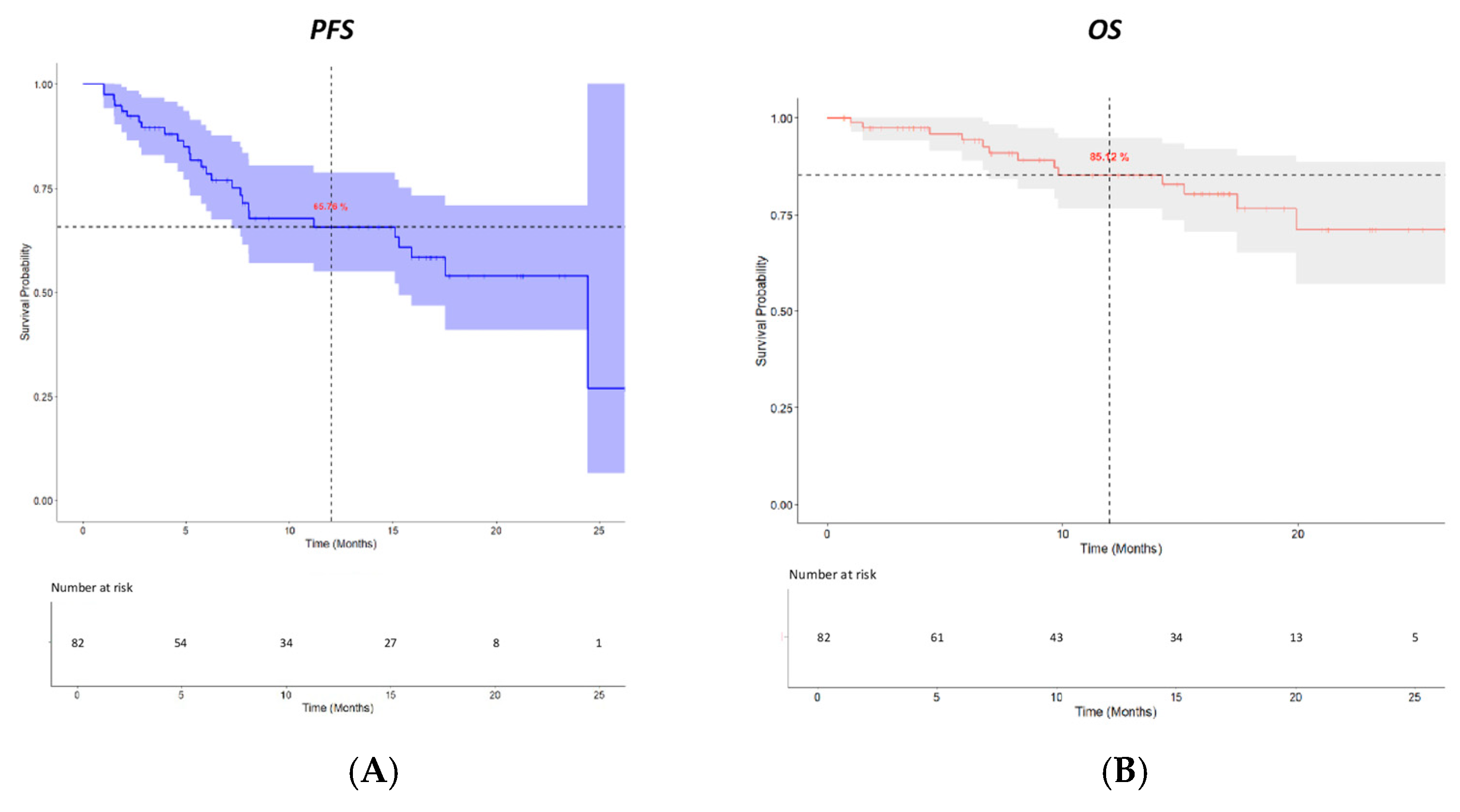

2.2. Efficacy

2.3. Safety

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients

4.2. Treatment

4.3. Endpoints

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Merz, M.; Dechow, T.; Scheytt, M.; Schmidt, C.; Hackanson, B.; Knop, S. The clinical management of lenalidomide-based therapy in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Ann. Hematol. 2020, 99, 1709–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreau, P.; Zamagni, E.; Mateos, M.V. Treatment of patients with multiple myeloma progressing on frontline-therapy with lenalidomide. Blood Cancer J. 2019, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botta, C.; Martino, E.A.; Conticello, C.; Mendicino, F.; Vigna, E.; Romano, A.; Palumbo, G.A.; Cerchione, C.; Martinelli, G.; Morabito, F.; et al. Treatment of Lenalidomide Exposed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma: Network Meta-Analysis of Lenalidomide-Sparing Regimens. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 643490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, A.; Chanan-Khan, A.; Weisel, K.; Nooka, A.K.; Masszi, T.; Beksac, M.; Spicka, I.; Hungria, V.; Munder, M.; Mateos, M.V.; et al. Daratumumab, Bortezomib, and Dexamethasone for Multiple Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.G.; Oriol, A.; Beksac, M.; Liberati, A.M.; Galli, M.; Schjesvold, F.; Lindsay, J.; Weisel, K.; White, D.; Facon, T.; et al. Pomalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma previously treated with lenalidomide (OPTIMISMM): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 781–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimopoulos, M.; Weisel, K.; Moreau, P.; Anderson, L.D., Jr.; White, D.; San-Miguel, J.; Sonneveld, P.; Engelhardt, M.; Jenner, M.; Corso, A.; et al. Pomalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma previously treated with lenalidomide (OPTIMISMM): Outcomes by prior treatment at first relapse. Leukemia 2021, 35, 1722–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, M.A.; Terpos, E.; Boccadoro, M.; Delimpasi, S.; Beksac, M.; Katodritou, E.; Moreau, P.; Baldini, L.; Symeonidis, A.; Bila, J.; et al. Daratumumab plus pomalidomide and dexamethasone versus pomalidomide and dexamethasone alone in previously treated multiple myeloma (APOLLO): An open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, P.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Mikhael, J.; Yong, K.; Capra, M.; Facon, T.; Hajek, R.; Špička, I.; Baker, R.; Kim, K.; et al. Isatuximab, carfilzomib, and dexamethasone in relapsed multiple myeloma (IKEMA): A multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 2361–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Mikhael, J.; Yong, K.; Capra, M.; Facon, T.; Hajek, R.; Špička, I.; Baker, R.; Kim, K.; et al. Isatuximab, carfilzomib, and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma: Updated results from IKEMA, a randomized Phase 3 study. Blood Cancer J. 2023, 13, 72, Erratum in Blood Cancer J. 2023, 13, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckert, J.; Wetzel, M.C.; Bartle, L.M.; Skaletskaya, A.; Goldmacher, V.S.; Vallée, F.; Zhou-Liu, Q.; Ferrari, P.; Pouzieux, S.; Lahoute, C.; et al. SAR650984, a novel humanized CD38-targeting antibody, demonstrates potent antitumor activity in models of multiple myeloma and other CD38+ hematologic malignancies. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 4574–4583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zhang, L.; Acharya, C.; An, G.; Wen, K.; Qiu, L.; Munshi, N.C.; Tai, Y.T.; Anderson, K.C. Targeting CD38 Suppresses Induction and Function of T Regulatory Cells to Mitigate Immunosuppression in Multiple Myeloma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 4290–4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perel, G.; Bliss, J.; Thomas, C.M. Carfilzomib (Kyprolis): A Novel Proteasome Inhibitor for Relapsed and/or Refractory Multiple Myeloma. Pharm. Ther. 2016, 41, 303–307. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.K.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Kastritis, E.; Terpos, E.; Nahi, H.; Goldschmidt, H.; Hillengass, J.; Leleu, X.; Beksac, M.; Alsina, M.; et al. Natural history of relapsed myeloma, refractory to immunomodulatory drugs and proteasome inhibitors: A multicenter IMWG study. Leukemia 2017, 31, 2443–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, U.H.; Cornell, R.F.; Lakshman, A.; Gahvari, Z.; McGehee, E.; Jagosky, M.H.; Gupta, R.; Varnado, W.; Fiala, M.A.; Chhabra, S.; et al. Outcomes of patients with multiple myeloma refractory to CD38-targeted monoclonal antibody therapy. Leukemia 2019, 33, 2266–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.K.; Therneau, T.M.; Gertz, M.A.; Lacy, M.Q.; Dispenzieri, A.; Rajkumar, S.V.; Fonseca, R.; Witzig, T.E.; Lust, J.A.; Larson, D.R.; et al. Clinical course of patients with relapsed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2004, 79, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majithia, N.; Rajkumar, S.V.; Lacy, M.Q.; Buadi, F.K.; Dispenzieri, A.; Gertz, M.A.; Hayman, S.R.; Dingli, D.; Kapoor, P.; Hwa, L.; et al. Early relapse following initial therapy for multiple myeloma predicts poor outcomes in the era of novel agents. Leukemia 2016, 30, 2208–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soekojo, C.Y.; Chung, T.H.; Furqan, M.S.; Chng, W.J. Genomic characterization of functional high-risk multiple myeloma patients. Blood Cancer J. 2022, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, M.A.; Moreau, P.; Terpos, E.; Mateos, M.V.; Zweegman, S.; Cook, G.; Delforge, M.; Hájek, R.; Schjesvold, F.; Cavo, M.; et al. Multiple Myeloma: EHA-ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-up. Hemasphere 2021, 5, e528, Erratum in Hemasphere 2021, 5, e567; Erratum in Hemasphere 2021, 5, e659. [Google Scholar]

- Kastritis, E.; Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, I.; Theodorakakou, F.; Migkou, M.; Roussou, M.; Malandrakis, P.; Kanellias, N.; Eleutherakis-Papaiakovou, E.; Fotiou, D.; Spiliopoulou, V.; et al. Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients with Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma After Exposure to Lenalidomide in First Line of Therapy: A Single Center Database Review in Greece. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2024, 24, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutani, M.; Foureau, D.M.; Robinson, M.; Guo, F.; Fesenkova, K.; Atrash, S.; Paul, B.; Varga, C.; Friend, R.; Pineda-Roman, M.; et al. A Clinical and Correlative Study of Elotuzumab, Carfilzomib, Lenalidomide, and Dexamethasone (Elo-KRd) for Lenalidomide Refractory Multiple Myeloma in First Relapse. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2023, 23, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzello, I.; Sacchetti, I.; Barbato, S.; Solli, V.; Stefanoni, P.; Cani, L.; Pavan, L.; Quaresima, M.; Belotti, A.; Sgherza, N.; et al. P-416 A Multicenter Observational Retrospective Study of Second-Line Treatment with Daratumumab-Bortezomib-Dexamethasone (DaraVd) in Multiple Myeloma (MM) Patients Refractory to Lenalidomide. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2024, 24, S275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Novellis, D.; Derudas, D.; Vincelli, D.; Fontana, R.; Della Pepa, R.; Palmieri, S.; Accardi, F.; Rotondo, F.; Morelli, E.; Gigliotta, E.; et al. Clinical Efficacy of Isatuximab Plus Carfilzomib and Dexamethasone in Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma Patients. Eur. J. Haematol. 2025, 114, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mele, G.; Sgherza, N.; Pastore, D.; Musto, P. Strengths and Weaknesses of Different Therapeutic Strategies for the Treatment of Patients with Multiple Myeloma Who Progress After the Frontline Use of Lenalidomide: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonneveld, P.; Zweegman, S.; Cavo, M.; Nasserinejad, K.; Broijl, A.; Troia, R.; Pour, L.; Croockewit, S.; Corradini, P.; Patriarca, F.; et al. Carfilzomib, Pomalidomide, and Dexamethasone as Second-line Therapy for Lenalidomide-refractory Multiple Myeloma. Hemasphere 2022, 6, e786, Erratum in Hemasphere 2023, 7, e856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beksac, M.; Spicka, I.; Hajek, R.; Bringhen, S.; Jelínek, T.; Martin, T.; Mikala, G.; Moreau, P.; Symeonidis, A.; Rawlings, A.M.; et al. Evaluation of isatuximab in patients with soft-tissue plasmacytomas: An analysis from ICARIA-MM and IKEMA. Leuk. Res. 2022, 122, 106948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, K.; Martin, T.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Mikhael, J.; Capra, M.; Facon, T.; Hajek, R.; Špička, I.; Baker, R.; Kim, K.; et al. Isatuximab plus carfilzomib-dexamethasone versus carfilzomib-dexamethasone in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma (IKEMA): Overall survival analysis of a phase 3, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Haematol. 2024, 11, e741–e750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaballa, M.R.; Martin, T.G.; Tsukada, N.; Suzuki, K.; Iriuchishima, H.; Chalayer, E.; Camus, V.; Alcala Peña, M.M.; Furlan, A.; Hubmann, M.C.G.; et al. Real-World Experience with Isatuximab in Patients with Relapsed and/or Refractory Multiple Myeloma (RRMM): Iona-MM Second Interim Analysis. Blood 2024, 144 (Suppl. 1), 2411.5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, K.; Fortuna, G.G.; Dahal, R.; Schmidt, T.; Fonseca, R.; Chakraborty, R.; Koehn, K.A.; Mohan, M.; Mian, H.; Costa, L.J.; et al. Alterations in chromosome 1q in multiple myeloma randomized clinical trials: A systematic review. Blood Cancer J. 2024, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, M.; Rota-Scalabrini, D.; Belotti, A.; Bertamini, L.; Arigoni, M.; De Sabbata, G.; Pietrantuono, G.; Pascarella, A.; Tosi, P.; Pisani, F.; et al. Additional copies of 1q negatively impact the outcome of multiple myeloma patients and induce transcriptomic deregulation in malignant plasma cells. Blood Cancer J. 2024, 14, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziccheddu, B.; Biancon, G.; Bagnoli, F.; De Philippis, C.; Maura, F.; Rustad, E.H.; Dugo, M.; Devecchi, A.; De Cecco, L.; Sensi, M.; et al. Integrative analysis of the genomic and transcriptomic landscape of double-refractory multiple myeloma. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 830–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.; Richardson, P.G.; Facon, T.; Moreau, P.; Perrot, A.; Spicka, I.; Bisht, K.; Inchauspé, M.; Casca, F.; Macé, S.; et al. Primary outcomes by 1q21+ status for isatuximab-treated patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: Subgroup analyses from ICARIA-MM and IKEMA. Haematologica 2022, 107, 2485–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Mahmood, S.T.; Lacy, M.Q.; Dispenzieri, A.; Hayman, S.R.; Buadi, F.K.; Dingli, D.; Rajkumar, S.V.; Litzow, M.R.; Gertz, M.A. Impact of early relapse after auto-SCT for multiple myeloma. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2008, 42, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Zepeda, V.H.; Reece, D.E.; Trudel, S.; Chen, C.; Tiedemann, R.; Kukreti, V. Early relapse after single auto-SCT for multiple myeloma is a major predictor of survival in the era of novel agents. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2015, 50, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Facon, T.; Moreau, P.; Baker, R.; Min, C.K.; Leleu, X.; Mohty, M.; Karlin, L.; Armstrong, N.M.; Tekle, C.; Schwab, S.; et al. Isatuximab plus carfilzomib and dexamethasone in patients with early versus late relapsed multiple myeloma: IKEMA subgroup analysis. Haematologica 2024, 109, 604–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavo, M.; Gay, F.; Beksac, M.; Pantani, L.; Petrucci, M.T.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Dozza, L.; van der Holt, B.; Zweegman, S.; Oliva, S.; et al. Autologous haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation versus bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone, with or without bortezomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone consolidation therapy, and lenalidomide maintenance for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (EMN02/HO95): A multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet Haematol. 2020, 7, e456–e468, Erratum in Lancet Haematol. 2020, 7, e443; Erratum in Lancet Haematol. 2020, 7, e785. [Google Scholar]

- Hari, P.N.; Pasquini, M.C.; Stadtmauer, E.A.; Fraser, R.; Fei, M.; Devine, S.M.; Efebera, Y.A.; Geller, N.L.; Horowitz, M.M.; Koreth, J.; et al. Long-term follow-up of BMT CTN 0702 (STaMINA) of postautologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (autoHCT) strategies in the upfront treatment of multiple myeloma (MM). J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 8506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durie, B.G.; Harousseau, J.L.; Miguel, J.S.; Bladé, J.; Barlogie, B.; Anderson, K.; Gertz, M.; Dimopoulos, M.; Westin, J.; Sonneveld, P.; et al. International uniform response criteria for multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2006, 20, 1467–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, S.V.; Harousseau, J.L.; Durie, B.; Anderson, K.C.; Dimopoulos, M.; Kyle, R.; Blade, J.; Richardson, P.; Orlowski, R.; Siegel, D.; et al. Consensus recommendations for the uniform reporting of clinical trials: Report of the International Myeloma Workshop Consensus Panel 1. Blood 2011, 117, 4691–4695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Median Age, Years (Range) | 62 (43–73) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 42 (51.2) |

| Female | 40 (48.8) |

| M-Protein Type, n (%) | |

| IgG | 47 (57.3) |

| IgA | 19 (23.2) |

| Light chain only | 15 (18.3) |

| Not secernent | 1 (1.2) |

| Light Chain Type, n (%) | |

| Kappa | 44 (53.7) |

| Lambda | 37 (45.1) |

| Not secreting | 1 (1.2) |

| Creatinine Clearance, n (%) | |

| <60 mL/min | 13 (15.8) |

| ≥60 mL/min | 69 (84.2) |

| LDH, n (%) | |

| Normal | 59 (72) |

| Elevated | 23 (28) |

| β2-Microglobulin (mg/L), n (%) | |

| <3.5 | 44 (53.7) |

| ≥3.5 <5.5 | 17 (20.7) |

| >5.5 | 12 (14.6) |

| Unknown or missing | 9 (11) |

| International Staging System (ISS), n (%) | |

| I | 38 (46.3) |

| II | 23 (28.1) |

| III | 12 (14.6) |

| Not available | 9 (11.0) |

| Type of Relapse, n (%) | |

| Laboratory | 15 (18.3) |

| Clinical | 67 (81.7) |

| FISH Analysis *, n (%; Considering Data Available for 50 Patients) | |

| High risk | 13 (26) |

| Standard risk | 37 (74) |

| 1q21 Abnormalities | 15 (30) |

| Gain(1q) | 9 (60) |

| Amp(1q) | 6 (40) |

| Extramedullary Disease, n (%) | 16 (19.5) |

| Induction Treatment Before ASCT, n (%) | |

| VTd | 71 (86.6) |

| D-VTd | 4 (4.9) |

| PAd | 3 (3.7) |

| VRd | 1 (1.2) |

| VCd | 3 (3.6) |

| Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation, n (%) | |

| Single | 44 (53.7) |

| Tandem | 38 (46.3) |

| Median Duration of Lenalidomide Maintenance, Months (Range) | 20 (1–61) |

| <12 months of lenalidomide maintenance; patients, n (%) | 25 (30.5) |

| <24 months of lenalidomide maintenance; patients, n (%) | 48 (58.5) |

| Cardiac Comorbidities Before Isa-Kdtreatment, n (%) | 27 (32.9) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 24 (29.3) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 3 (3.6) |

| Hematological Toxicity (Grades III and IV), n (%) | |

| Thrombocytopenia | 25 (30.5) |

| Lymphocytopenia | 16 (19.5) |

| Neutropenia | 14 (17.1) |

| Anemia | 9 (10.9) |

| Cardiac Toxicity (Grades I and II), n (%) | |

| Hypertension | 11 (13.4) |

| Infectious Events (Any Grade), n (%) | |

| Pneumonia | 11 (13.4) |

| Upper airway infection | 11 (13.4) |

| SARS-CoV-2 infection | 4 (4.9) |

| Sepsis | 3 (3.6) |

| CMV * infection | 2 (2.4) |

| HZV ** infection | 1 (1.2) |

| Conjunctivitis | 1 (1.2) |

| Cellulitis | 1 (1.2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sgherza, N.; Battisti, O.; Curci, P.; Conticello, C.; Palmieri, S.; Derudas, D.; Germano, C.; Martino, E.A.; Mele, G.; Della Pepa, R.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Isatuximab, Carfilzomib, and Dexamethasone (IsaKd) in Multiple Myeloma Patients at the First Relapse After Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation and Lenalidomide Maintenance: Results from the Multicenter, Real-Life AENEID Study. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 595. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18040595

Sgherza N, Battisti O, Curci P, Conticello C, Palmieri S, Derudas D, Germano C, Martino EA, Mele G, Della Pepa R, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Isatuximab, Carfilzomib, and Dexamethasone (IsaKd) in Multiple Myeloma Patients at the First Relapse After Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation and Lenalidomide Maintenance: Results from the Multicenter, Real-Life AENEID Study. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(4):595. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18040595

Chicago/Turabian StyleSgherza, Nicola, Olga Battisti, Paola Curci, Concetta Conticello, Salvatore Palmieri, Daniele Derudas, Candida Germano, Enrica Antonia Martino, Giuseppe Mele, Roberta Della Pepa, and et al. 2025. "Efficacy and Safety of Isatuximab, Carfilzomib, and Dexamethasone (IsaKd) in Multiple Myeloma Patients at the First Relapse After Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation and Lenalidomide Maintenance: Results from the Multicenter, Real-Life AENEID Study" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 4: 595. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18040595

APA StyleSgherza, N., Battisti, O., Curci, P., Conticello, C., Palmieri, S., Derudas, D., Germano, C., Martino, E. A., Mele, G., Della Pepa, R., Fazio, F., Mele, A., Rossini, B., Palazzo, G., Roccotelli, D., Rasola, S., Petrucci, M. T., Pastore, D., Tarantini, G., ... Musto, P. (2025). Efficacy and Safety of Isatuximab, Carfilzomib, and Dexamethasone (IsaKd) in Multiple Myeloma Patients at the First Relapse After Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation and Lenalidomide Maintenance: Results from the Multicenter, Real-Life AENEID Study. Pharmaceuticals, 18(4), 595. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18040595