Integrated Transcriptomic, Proteomic, and Network Pharmacology Analyses Unravel Key Therapeutic Mechanisms of Xuebijing Injection for Severe Acute Pancreatitis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification of Active Ingredients and Targets Prediction of XBJ

2.2. XBJ Attenuates Pancreatic and Lung Injury in SAP Mice

2.3. XBJ Reduces Inflammatory Responses in SAP Mice

2.4. XBJ Alleviates PAC Injury

2.5. Network Pharmacology Analysis of XBJ in SAP Based on Human Blood Transcriptomics

2.6. Network Pharmacology Analysis of XBJ in SAP Based on Mouse Blood Transcriptomics

2.7. Network Pharmacology Analysis of XBJ in SAP Based on Mouse Lung Tissue Transcriptomics

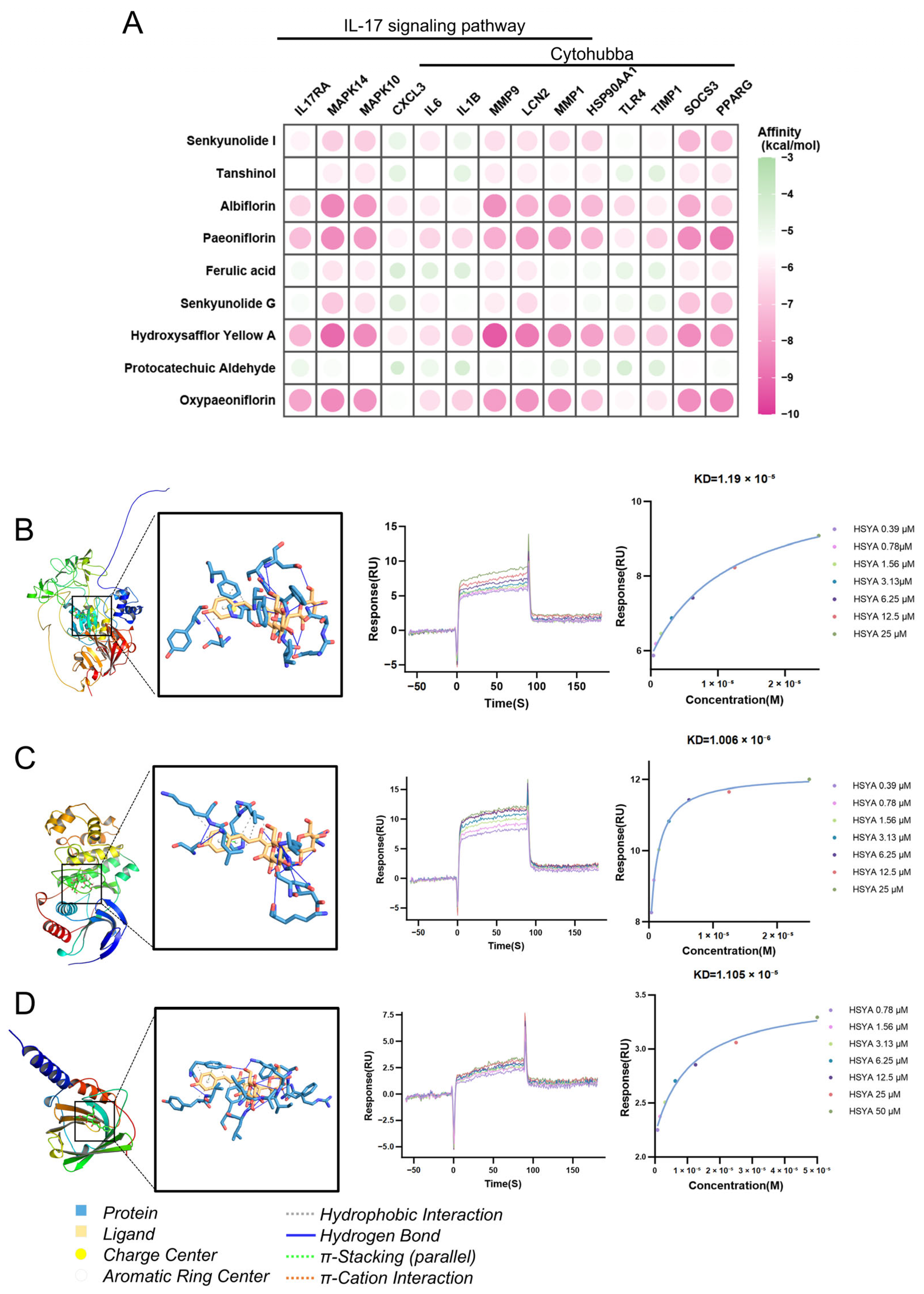

2.8. Therapeutic Effects of XBJ in SAP: Hub Targets Recognition, Molecular Docking, and Immune Cell Infiltration

2.9. XBJ Treatment Attenuates Severity of SAP Partially via Suppressing IL-17-Related Signaling Pathways

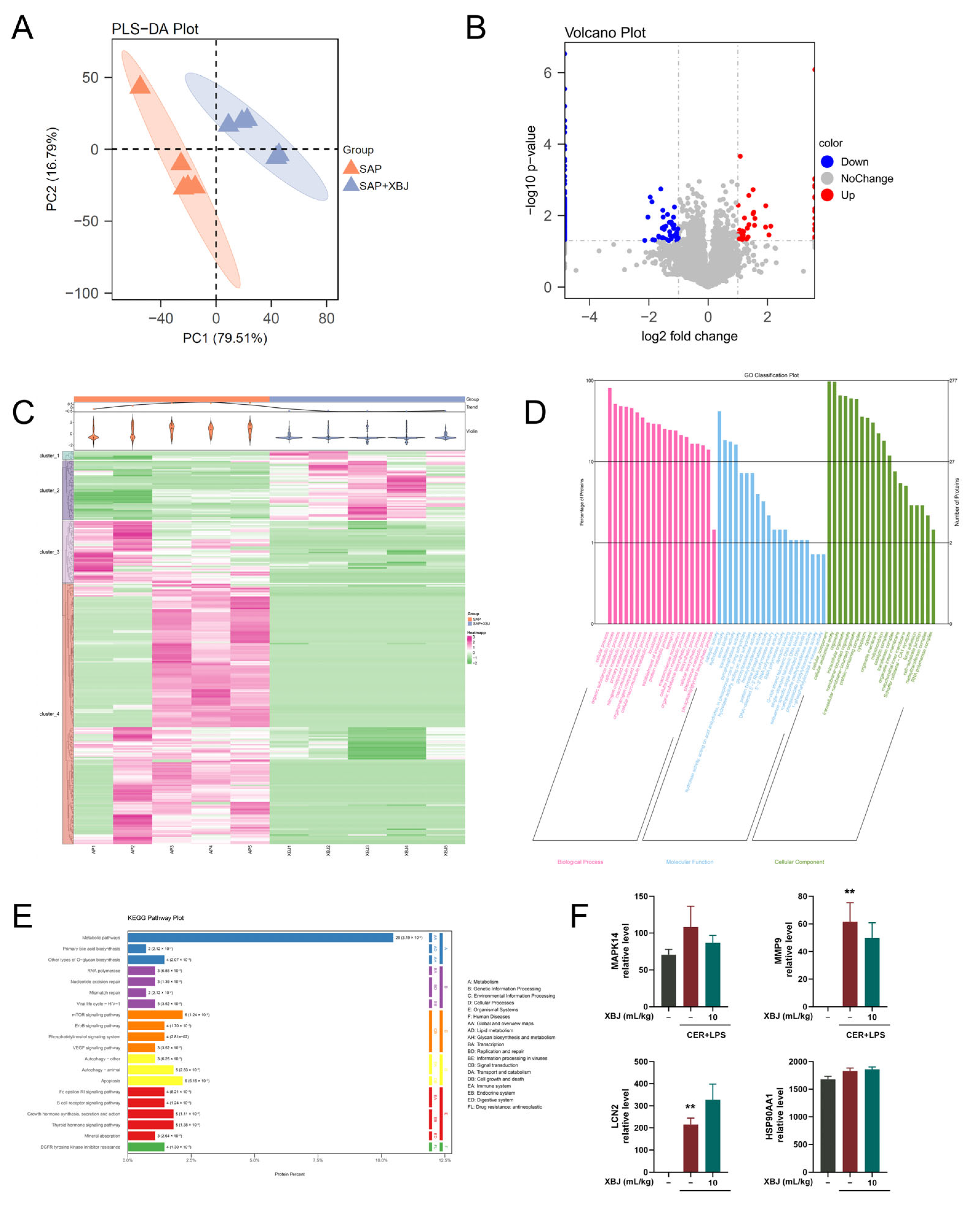

2.10. Proteomic Analysis of XBJ Treatment in SAP Mice

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethics and Animals

4.2. Materials and Reagents

4.3. UPLC-QTOF/MS Analysis of XBJ and Standards

4.4. SAP Model Induction and Treatment

4.5. Histological Analysis and Immunostaining

4.6. Serum Cytokine Profiling

4.7. RT-qPCR and Western Blotting

4.8. Necrotic Cell Death Assay

4.9. Transcriptome Analysis of Peripheral Blood from SAP Patients

4.10. Transcriptome Analysis of Blood and Lung Tissue from SAP Mice

4.11. Functional and Pathway Enrichment Analysis

4.12. Network Pharmacology Analysis

4.13. Proteomics of Pancreatic Tissue in SAP Mice

4.14. Immune Cell Infiltration Analysis in SAP Patients

4.15. Molecular Docking Analysis and Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Assay

4.16. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CHM | Chinese herbal medicine |

| DAPI | 4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| DEGs | differentially expressed genes |

| DEPs | differentially expressed proteins |

| ETCM | The Encyclopedia of Traditional Chinese Medicine |

| FC | fold change |

| GEO | Gene Expression Omnibus |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| HSYA | hydroxysafflor yellow A |

| MCODE | Molecular Complex Detection |

| PACs | Pancreatic acinar cells |

| PI | propidium iodide |

| PLS-DA | partial least squares discriminant analysis |

| PPI | protein–protein interaction |

| RCTs | randomized controlled trials |

| SAP | severe acute pancreatitis |

| STITCH | Search Tool For Interactions of Chemicals |

| TCMSP | Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database and Analysis Platform |

| TLCS | taurolithocholic acid 3-sulfate disodium salt |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| XBJ | Xuebijing Injection |

References

- Iannuzzi, J.P.; King, J.A.; Leong, J.H.; Quan, J.; Windsor, J.W.; Tanyingoh, D.; Coward, S.; Forbes, N.; Heitman, S.J.; Shaheen, A.A.; et al. Global Incidence of Acute Pancreatitis Is Increasing Over Time: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenner, S.; Vege, S.S.; Sheth, S.G.; Sauer, B.; Yang, A.; Conwell, D.L.; Yadlapati, R.H.; Gardner, T.B. American College of Gastroenterology Guidelines: Management of Acute Pancreatitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 119, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schepers, N.J.; Bakker, O.J.; Besselink, M.G.; Ahmed Ali, U.; Bollen, T.L.; Gooszen, H.G.; van Santvoort, H.C.; Bruno, M.J.; Dutch Pancreatitis Study, G. Impact of characteristics of organ failure and infected necrosis on mortality in necrotising pancreatitis. Gut 2019, 68, 1044–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szatmary, P.; Grammatikopoulos, T.; Cai, W.; Huang, W.; Mukherjee, R.; Halloran, C.; Beyer, G.; Sutton, R. Acute Pancreatitis: Diagnosis and Treatment. Drugs 2022, 82, 1251–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Huo, D.; Wu, Q.; Zhu, L.; Liao, Y. Xuebijing for paraquat poisoning. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 7, CD010109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Yin, S.; Zhou, L.; Li, Z.; Yan, H.; Zhong, Y.; Wu, X.; Luo, B.; Yang, L.; Gan, D.; et al. Chinese herbal medicine xuebijing injection for acute pancreatitis: An overview of systematic reviews. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 883729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Qian, Y.; Miao, Z.; Zheng, P.; Shi, T.; Jiang, X.; Pan, L.; Qian, F.; Yang, G.; An, H.; et al. Xuebijing Injection Alleviates Pam3CSK4-Induced Inflammatory Response and Protects Mice From Sepsis Caused by Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zheng, R.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, X.; Peng, M.; Jiang, T.; Zhang, X.; Shang, H. Therapeutic efficacy of Xuebijing injection in treating severe acute pancreatitis and its mechanisms of action: A comprehensive survey. Phytomedicine 2025, 140, 156629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkermann, A.; Stockwell, B.R.; Krautwald, S.; Anders, H.J. Regulated cell death and inflammation: An auto-amplification loop causes organ failure. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Gutierrez-Castrellon, P.; Shi, H. Cell deaths: Involvement in the pathogenesis and intervention therapy of COVID-19. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, R.; Lotze, M.T.; Zeh, H.J.; Billiar, T.R.; Tang, D. Cell death and DAMPs in acute pancreatitis. Mol. Med. 2014, 20, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.; Li, Z.; Ren, Y.; Wang, M.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Han, X.; Yao, M.; Sun, Z.; Nie, S. Xuebijing Protects Against Septic Acute Liver Injury Based on Regulation of GSK-3beta Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 627716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Lai, X.; Wang, X.; Yao, X.; Wang, W.; Li, S. Network pharmacology to explore the anti-inflammatory mechanism of Xuebijing in the treatment of sepsis. Phytomedicine 2021, 85, 153543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.D.; Zhang, X.K.; Zhu, X.Y.; Huang, F.F.; Wang, Z.; Tu, J.C. Network pharmacology and RNA-sequencing reveal the molecular mechanism of Xuebijing injection on COVID-19-induced cardiac dysfunction. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 131, 104293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, W.; Wang, L.; Wang, B.; Zhang, T.; Li, S. Network pharmacology: Towards the artificial intelligence-based precision traditional Chinese medicine. Brief. Bioinform. 2023, 25, bbad518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.J.; Papachristou, G.I.; Speake, C.; Lacy-Hulbert, A. Immune markers of severe acute pancreatitis. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2024, 40, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateu, A.; Ramudo, L.; Manso, M.A.; De Dios, I. Cross-talk between TLR4 and PPARgamma pathways in the arachidonic acid-induced inflammatory response in pancreatic acini. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2015, 69, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.J.; Lim, J.W.; Kim, H. Lutein inhibits IL-6 expression by inducing PPAR-gamma activation and SOCS3 expression in cerulein-stimulated pancreatic acinar cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2022, 26, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, K.H.G. IL-17 and IL-17-producing cells in protection versus pathology. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaubitz, J.; Wilden, A.; Frost, F.; Ameling, S.; Homuth, G.; Mazloum, H.; Ruhlemann, M.C.; Bang, C.; Aghdassi, A.A.; Budde, C.; et al. Activated regulatory T-cells promote duodenal bacterial translocation into necrotic areas in severe acute pancreatitis. Gut 2023, 72, 1355–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Xiong, H.; Li, W.; Li, B.; Cheng, Y. Upregulation of IL-6 expression in human salivary gland cell line by IL-17 via activation of p38 MAPK, ERK, PI3K/Akt, and NF-kappaB pathways. J. Oral. Pathol. Med. 2018, 47, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGeachy, M.J.; Cua, D.J.; Gaffen, S.L. The IL-17 Family of Cytokines in Health and Disease. Immunity 2019, 50, 892–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Fan, M.; Li, X.; Yu, F.; Zhou, E.; Han, X. Molecular mechanism of Xuebijing in treating pyogenic liver abscess complicated with sepsis. World J. Emerg. Med. 2024, 15, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreto, S.G.; Habtezion, A.; Gukovskaya, A.; Lugea, A.; Jeon, C.; Yadav, D.; Hegyi, P.; Venglovecz, V.; Sutton, R.; Pandol, S.J. Critical thresholds: Key to unlocking the door to the prevention and specific treatments for acute pancreatitis. Gut 2021, 70, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Dominguez, R.; de la Fuente, H.; Rodriguez, C.; Martin-Aguado, L.; Sanchez-Diaz, R.; Jimenez-Alejandre, R.; Rodriguez-Arabaolaza, I.; Curtabbi, A.; Garcia-Guimaraes, M.M.; Vera, A.; et al. CD69 expression on regulatory T cells protects from immune damage after myocardial infarction. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e152418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.Y.; Lee, A.R.; Choi, J.W.; Lee, C.R.; Cho, K.H.; Lee, J.H.; Cho, M.L. IL-17 Induces Autophagy Dysfunction to Promote Inflammatory Cell Death and Fibrosis in Keloid Fibroblasts via the STAT3 and HIF-1alpha Dependent Signaling Pathways. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 888719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.J.; Papachristou, G.I. New insights into acute pancreatitis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Cao, A.; Yao, S.; Evans-Marin, H.L.; Liu, H.; Wu, W.; Carlsen, E.D.; Dann, S.M.; Soong, L.; Sun, J.; et al. mTOR Mediates IL-23 Induction of Neutrophil IL-17 and IL-22 Production. J. Immunol. 2016, 196, 4390–4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Niu, W.; Wang, Y.Y.; Olaleye, O.E.; Wang, J.N.; Duan, M.Y.; Yang, J.L.; He, R.R.; Chu, Z.X.; Dong, K.; et al. Novel assays for quality evaluation of XueBiJing: Quality variability of a Chinese herbal injection for sepsis management. J. Pharm. Anal. 2022, 12, 664–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.T.; Peng, Z.; An, Y.Y.; Shang, T.; Xiao, G.; He, S.; Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, T.; et al. Paeoniflorin and Hydroxysafflor Yellow A in Xuebijing Injection Attenuate Sepsis-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction and Inhibit Proinflammatory Cytokine Production. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 614024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yao, L.; Yuan, M.; Zhang, X.; Jakubowska, M.A.; Ferdek, P.E.; Dai, L.; Yang, J.; Jin, T.; Deng, L.; et al. Transcriptomics and Network Pharmacology Reveal the Protective Effect of Chaiqin Chengqi Decoction on Obesity-Related Alcohol-Induced Acute Pancreatitis via Oxidative Stress and PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 896523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Yao, L.; Fu, X.; Mukherjee, R.; Xia, Q.; Jakubowska, M.A.; Ferdek, P.E.; Huang, W. Experimental Acute Pancreatitis Models: History, Current Status, and Role in Translational Research. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 614591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, P.A.; Bollen, T.L.; Dervenis, C.; Gooszen, H.G.; Johnson, C.D.; Sarr, M.G.; Tsiotos, G.G.; Vege, S.S.; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working, G. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: Revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut 2013, 62, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, J.; Li, P.; Wang, J.; Zhou, W.; Li, B.; Huang, C.; Li, P.; Guo, Z.; Tao, W.; Yang, Y.; et al. TCMSP: A database of systems pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. J. Cheminform. 2014, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Liu, Z.M.; Chen, T.; Lv, C.Y.; Tang, S.H.; Zhang, X.B.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z.Y.; Zhou, R.R.; et al. ETCM: An encyclopaedia of traditional Chinese medicine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D976–D982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Dong, L.; Liu, L.; Guo, J.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, J.; Bu, D.; Liu, X.; Huo, P.; Cao, W.; et al. HERB: A high-throughput experiment- and reference-guided database of traditional Chinese medicine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D1197–D1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Santos, A.; von Mering, C.; Jensen, L.J.; Bork, P.; Kuhn, M. STITCH 5: Augmenting protein-chemical interaction networks with tissue and affinity data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D380–D384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Lee, M.K.; Jang, H.; Lee, J.J.; Lee, S.; Jang, Y.; Jang, H.; Kim, A. TM-MC 2.0: An enhanced chemical database of medicinal materials in Northeast Asian traditional medicine. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2024, 24, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissTargetPrediction: Updated data and new features for efficient prediction of protein targets of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W357–W364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Nastou, K.C.; Lyon, D.; Kirsch, R.; Pyysalo, S.; Doncheva, N.T.; Legeay, M.; Fang, T.; Bork, P.; et al. The STRING database in 2021: Customizable protein-protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, D605–D612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adasme, M.F.; Linnemann, K.L.; Bolz, S.N.; Kaiser, F.; Salentin, S.; Haupt, V.J.; Schroeder, M. PLIP 2021: Expanding the scope of the protein-ligand interaction profiler to DNA and RNA. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, W530–W534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yao, L.; Yang, X.; Yuan, M.; Liu, S.; Wang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Luo, W.; Wu, X.; Cai, W.; Li, L.; et al. Integrated Transcriptomic, Proteomic, and Network Pharmacology Analyses Unravel Key Therapeutic Mechanisms of Xuebijing Injection for Severe Acute Pancreatitis. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1866. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121866

Yao L, Yang X, Yuan M, Liu S, Wang Q, Wu Y, Luo W, Wu X, Cai W, Li L, et al. Integrated Transcriptomic, Proteomic, and Network Pharmacology Analyses Unravel Key Therapeutic Mechanisms of Xuebijing Injection for Severe Acute Pancreatitis. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1866. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121866

Chicago/Turabian StyleYao, Linbo, Xinmin Yang, Mei Yuan, Shiyu Liu, Qiqi Wang, Yongzi Wu, Wenjuan Luo, Xueying Wu, Wenhao Cai, Lan Li, and et al. 2025. "Integrated Transcriptomic, Proteomic, and Network Pharmacology Analyses Unravel Key Therapeutic Mechanisms of Xuebijing Injection for Severe Acute Pancreatitis" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1866. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121866

APA StyleYao, L., Yang, X., Yuan, M., Liu, S., Wang, Q., Wu, Y., Luo, W., Wu, X., Cai, W., Li, L., Lin, Z., Yang, J., Liu, T., Sutton, R., Szatmary, P., Jin, T., Xia, Q., & Huang, W. (2025). Integrated Transcriptomic, Proteomic, and Network Pharmacology Analyses Unravel Key Therapeutic Mechanisms of Xuebijing Injection for Severe Acute Pancreatitis. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1866. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121866