Reinvestigating Pyrrol-2-One-Based Compounds: From Antimicrobial Agents to Promising Antitumor Candidates

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussions

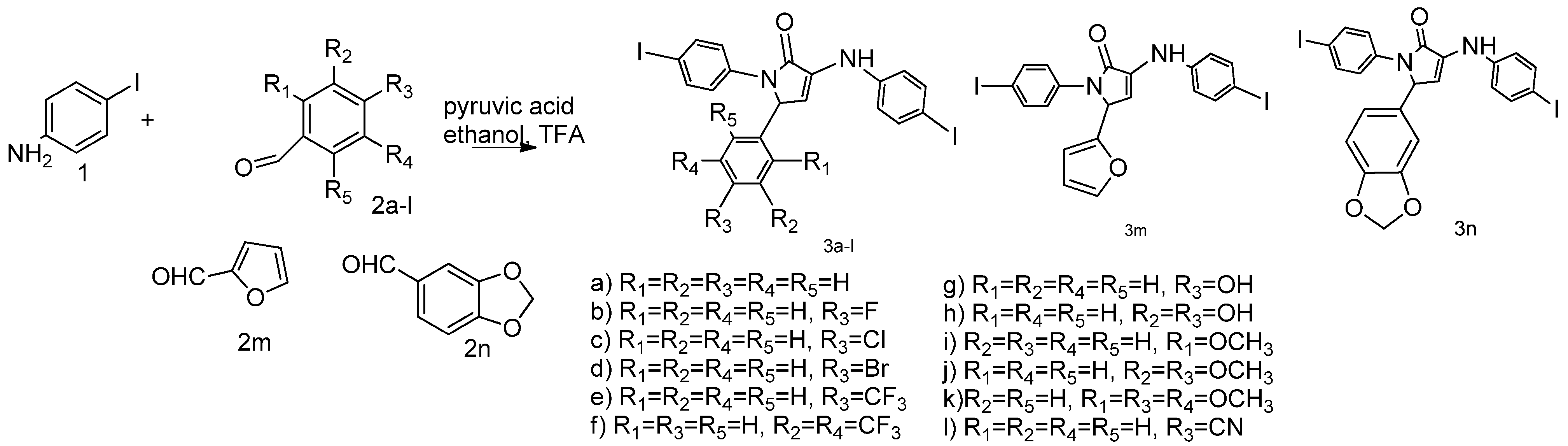

2.1. Synthesis

2.2. In Silico Adsorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion (ADME) and Toxicity Predictions

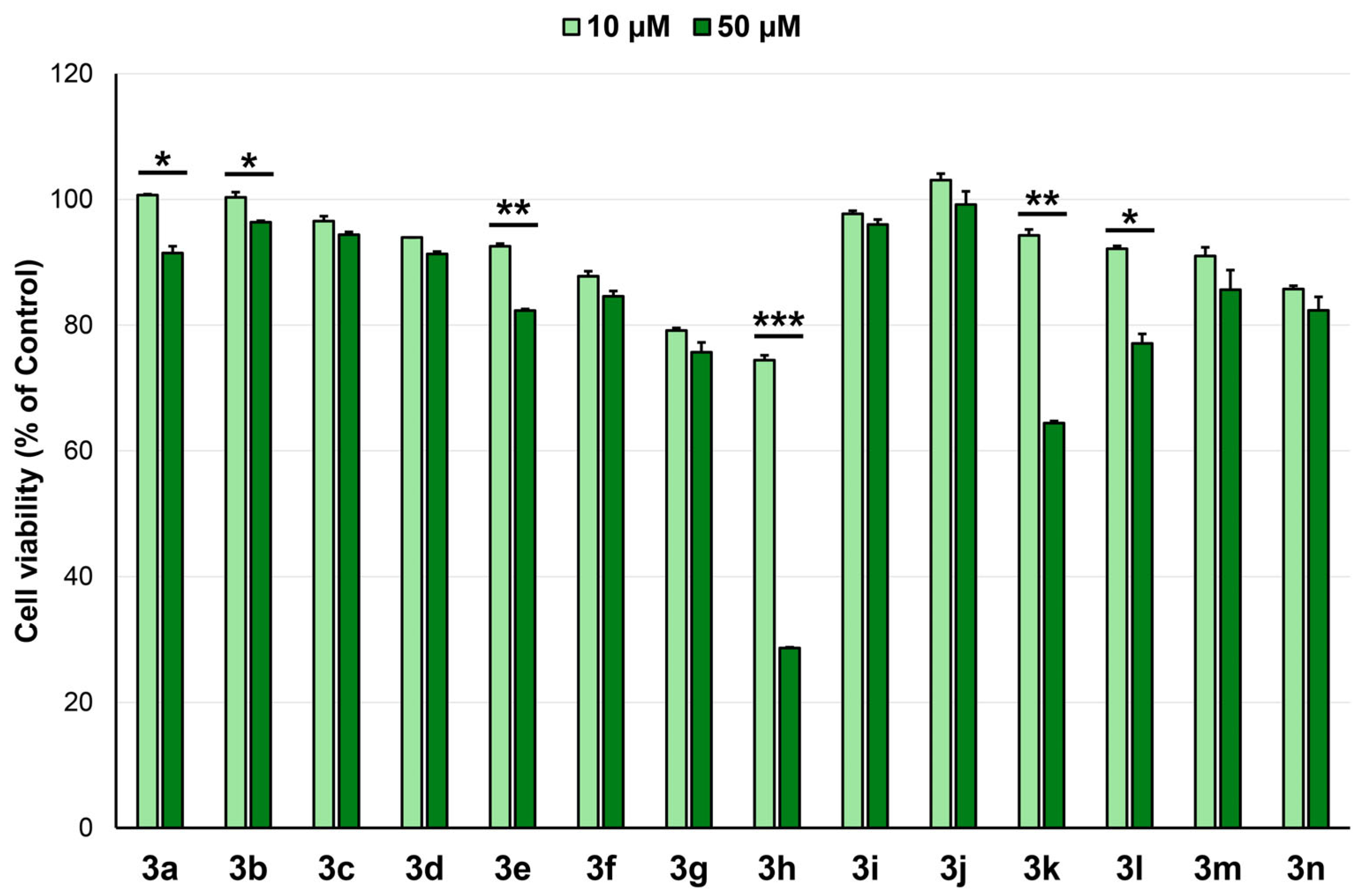

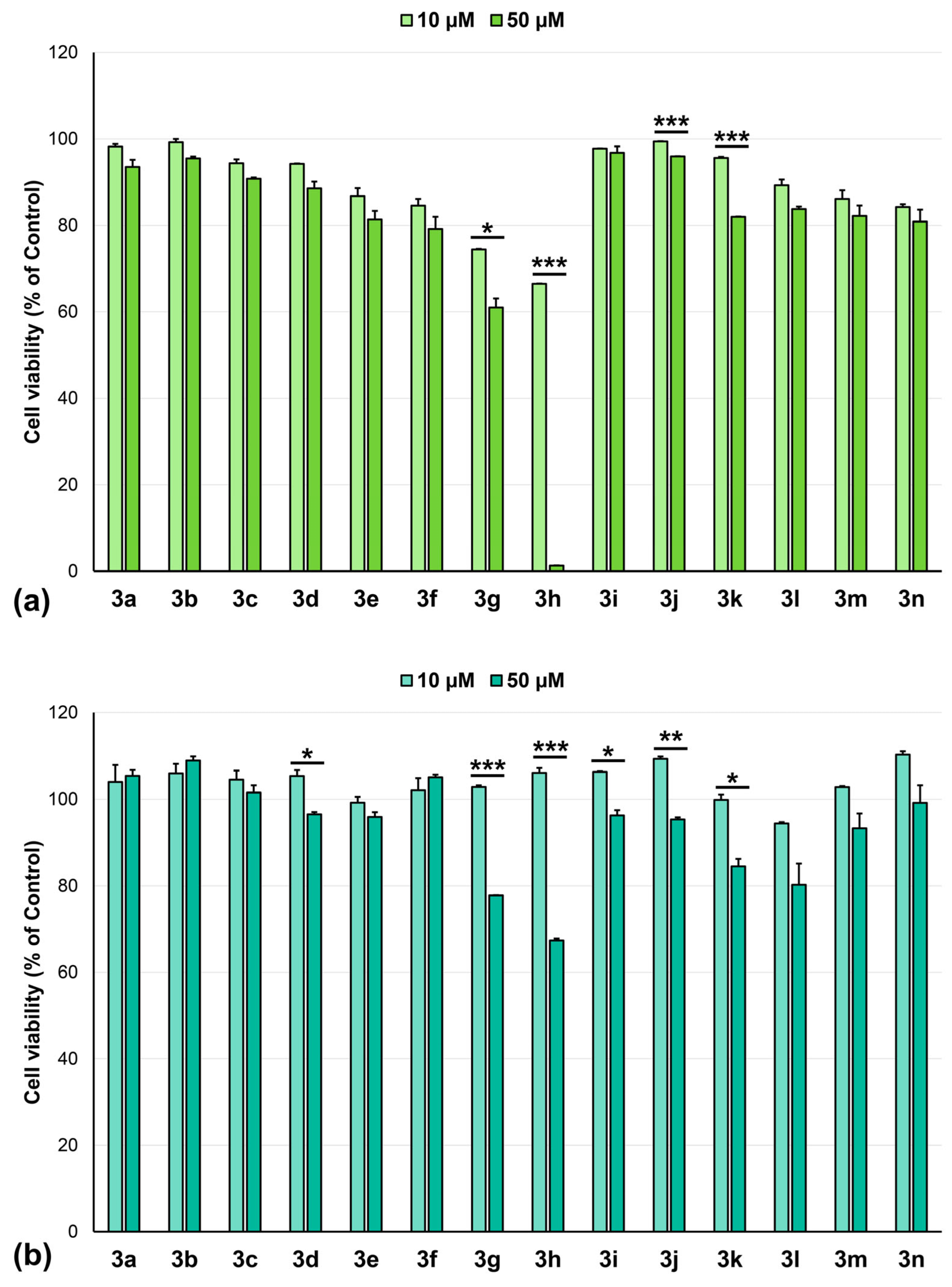

2.3. Anticancer Activity

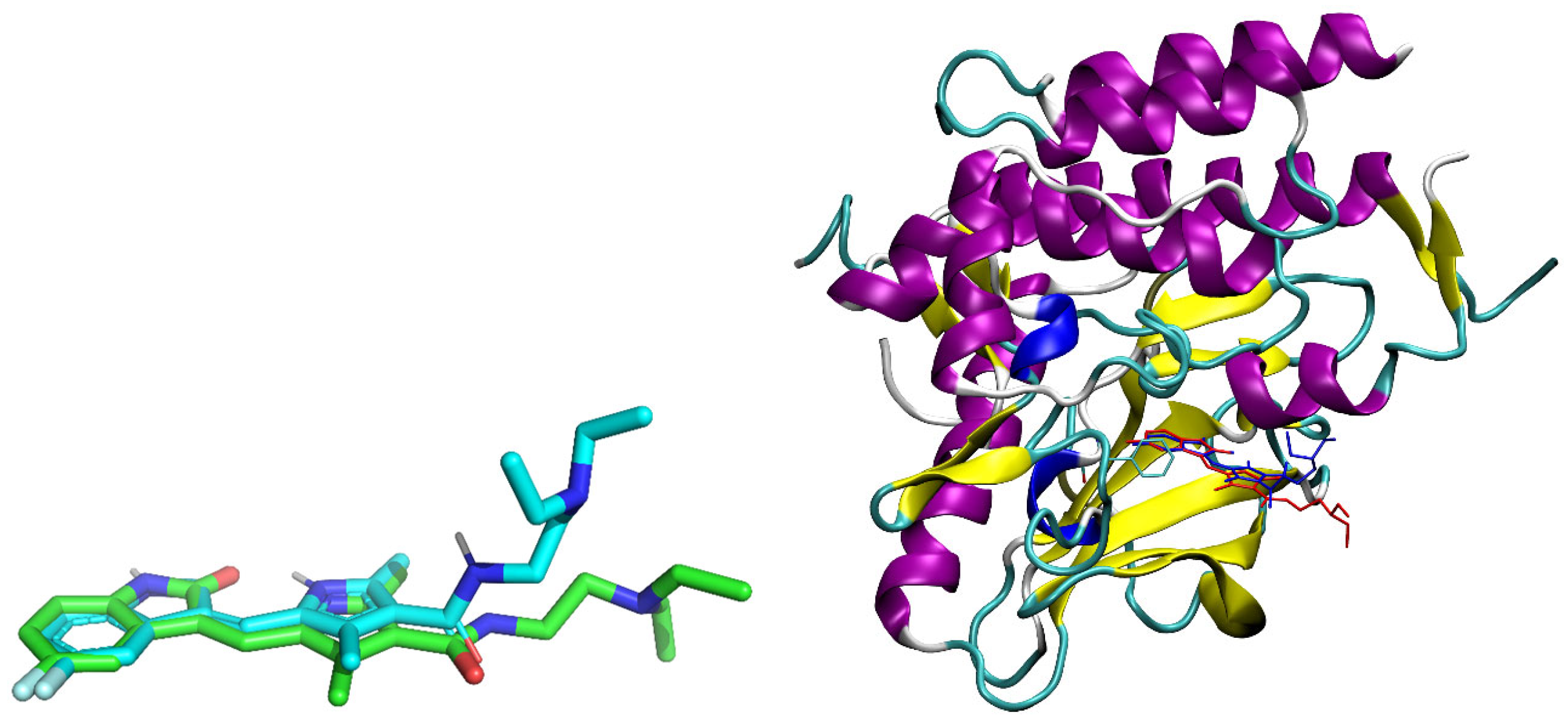

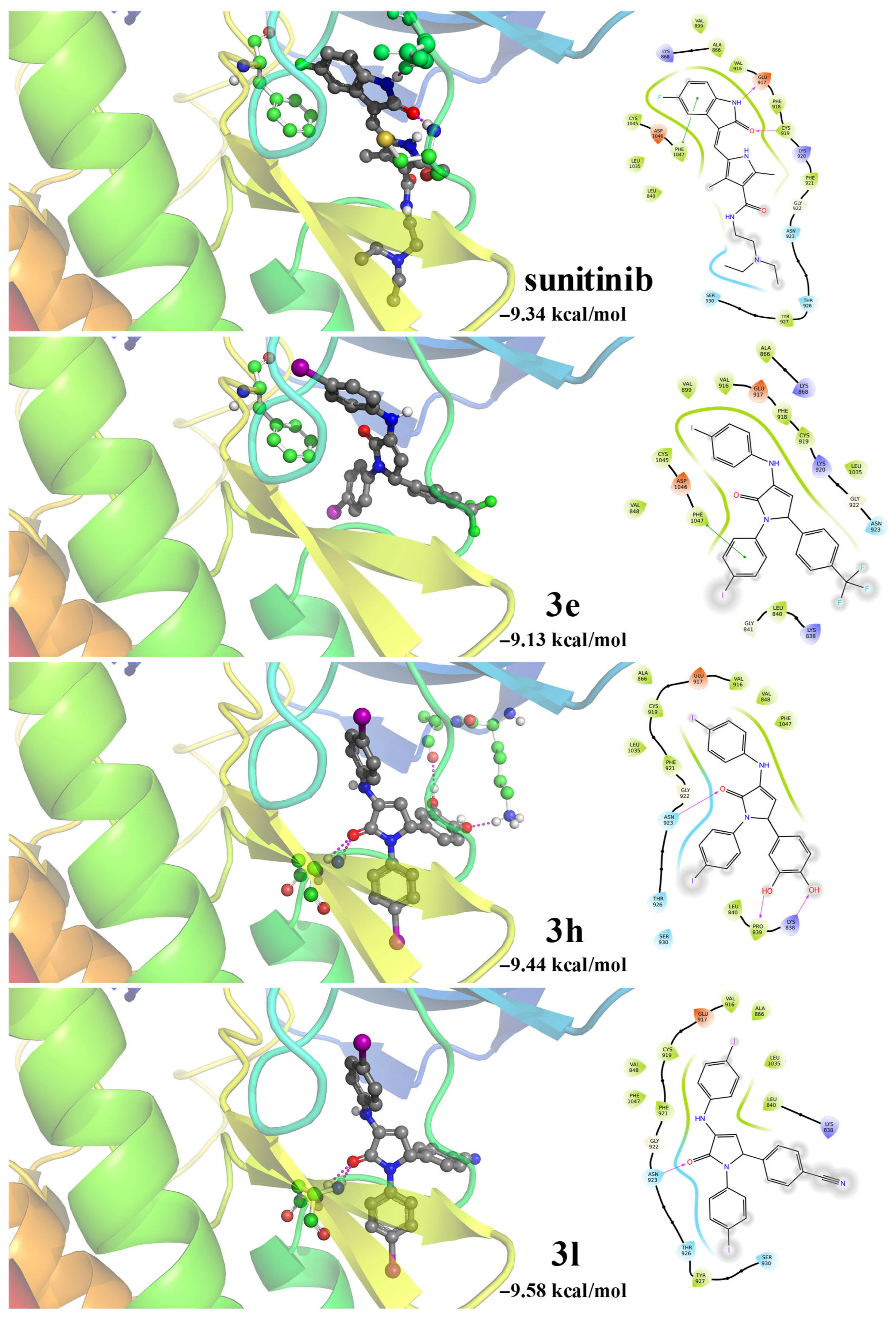

2.4. Molecular Docking

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. In Silico ADME and Toxicity Predictions

3.2. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assessment

3.3. Molecular Docking

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Available online: https://www.who.int/Health-Topics/Cancer#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Available online: https://www.iarc.who.int/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhra, M.; Akhund, S.A.; Mohammad, K.S. Advancements in Osteosarcoma Therapy: Overcoming Chemotherapy Resistance and Exploring Novel Pharmacological Strategies. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picci, P. Osteosarcoma (Osteogenic Sarcoma). Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2007, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durfee, R.A.; Mohammed, M.; Luu, H.H. Review of Osteosarcoma and Current Management. Rheumatol. Ther. 2016, 3, 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitaku, E.; Smith, D.T.; Njardarson, J.T. Analysis of the Structural Diversity, Substitution Patterns, and Frequency of Nitrogen Heterocycles among U.S. FDA Approved Pharmaceuticals. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 10257–10274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, C.M.; Federice, J.G.; Bell, C.N.; Cox, P.B.; Njardarson, J.T. An Update on the Nitrogen Heterocycle Compositions and Properties of U.S. FDA-Approved Pharmaceuticals (2013–2023). J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 11622–11655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Liu, Y.; Qin, H.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, S.; He, W.; Tang, S.; Peng, J. Nitrogen-Containing Heterocyclic Drug Products Approved by the FDA in 2023: Synthesis and Biological Activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 279, 116838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.R.; Jaiswal, S.; Kukkar, D.; Kumar, R.; Singh, T.G.; Singh, M.P.; Gaidhane, A.M.; Lakhanpal, S.; Prasad, K.N.; Kumar, B. A Decade of Pyridine-Containing Heterocycles in US FDA Approved Drugs: A Medicinal Chemistry-Based Analysis. RSC Med. Chem. 2025, 16, 12–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.A.; Farghaly, T.A.; Dawood, K.M. Recent Advances on Anticancer and Antimicrobial Activities of Directly-Fluorinated Five-Membered Heterocycles and Their Benzo-Fused Systems. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 19752–19779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.A.; Refaat, H.M. Versatile Mechanisms of 2-Substituted Benzimidazoles in Targeted Cancer Therapy. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 6, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, T.S.; Kulhari, H.; Reddy, V.G.; Bansal, V.; Kamal, A.; Shukla, R. Design, Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of 1,3-Diphenyl-1 H-Pyrazole Derivatives Containing Benzimidazole Skeleton as Potential Anticancer and Apoptosis Inducing Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 101, 790–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznietsova, H.; Dziubenko, N.; Byelinska, I.; Hurmach, V.; Bychko, A.; Lynchak, O.; Milokhov, D.; Khilya, O.; Rybalchenko, V. Pyrrole Derivatives as Potential Anti-Cancer Therapeutics: Synthesis, Mechanisms of Action, Safety. J. Drug Target. 2020, 28, 547–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeleebia, T.M.; Jasim Naser, M.; Saeed, S.M.; Abid, M.M.; Altimari, U.S.; Shaghnab, M.L.; Rasen, F.A.; Alawadi, A.; Ahmad, I.; Alsalamy, A. Multi-Component Synthesis and Invitro Biological Assessment of Novel Pyrrole Derivatives and Pyrano [2,3-c] Pyrazole Derivatives Using Co3O4 Nanoparticles as Recyclable Nanocatalyst. Front. Mater. 2024, 11, 1354560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, Y.; Erez, T.; Reynolds, I.J.; Kumar, D.; Ross, J.; Koytiger, G.; Kusko, R.; Zeskind, B.; Risso, S.; Kagan, E.; et al. Drug Repurposing from the Perspective of Pharmaceutical Companies. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohi-ud-din, R.; Chawla, A.; Sharma, P.; Mir, P.A.; Potoo, F.H.; Reiner, Ž.; Reiner, I.; Ateşşahin, D.A.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Mir, R.H.; et al. Repurposing Approved Non-Oncology Drugs for Cancer Therapy: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanisms, Efficacy, and Clinical Prospects. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2023, 28, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudrapal, M.; Khairnar, S.J.; Jadhav, G.A. Drug Repurposing (DR): An Emerging Approach in Drug Discovery. In Drug Repurposing—Hypothesis, Molecular Aspects and Therapeutic Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sajwani, N.; Suchitha, G.P.; Keshava Prasad, T.S.; Dagamajalu, S. Drug Repurposing in Oncology: A Path beyond the Bottleneck. Med. Oncol. 2025, 42, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranraj, K.; Kiran, P.U. Drug Repurposing: Clinical Practices and Regulatory Pathways. Perspect. Clin. Res. 2025, 16, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Bergeron, E.; Senta, H.; Guillemette, K.; Beauvais, S.; Blouin, R.; Sirois, J.; Faucheux, N. Sanguinarine Induces Apoptosis of Human Osteosarcoma Cells through the Extrinsic and Intrinsic Pathways. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 399, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.-C.; Liao, K.-S.; Yeh, L.-R.; Wang, Y.-K. Drug Repurposing: The Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways of Anti-Cancer Effects of Anesthetics. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischof Delaloye, A. The Role of Nuclear Medicine in the Treatment of Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (NHL). Leuk. Lymphoma 2003, 44, S29–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palot Manzil, F.F.; Kaur, H. Radioactive Iodine Therapy for Thyroid Malignancies; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cline, B.L.; Jiang, W.; Lee, C.; Cao, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhan, S.; Chong, H.; Zhang, T.; Han, Z.; Wu, X.; et al. Potassium Iodide Nanoparticles Enhance Radiotherapy against Breast Cancer by Exploiting the Sodium-Iodide Symporter. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 17401–17411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenberg, T.; Larsson, O.; Hedin, B.; Shiraki, S.; Karita, T. Iodine Loaded Nanoparticles with Commercial Applicability Increase Survival in Mice Cancer Models with Low Degree of Side Effects. Cancer Rep. 2023, 6, e1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Matarneh, C.M.; Nicolescu, A.; Marinaş, I.C.; Găboreanu, M.D.; Shova, S.; Dascălu, A.; Silion, M.; Pinteală, M. New Library of Iodo-Quinoline Derivatives Obtained by an Alternative Synthetic Pathway and Their Antimicrobial Activity. Molecules 2024, 29, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Matarneh, C.M.; Nicolescu, A.; Marinas, I.C.; Chifiriuc, M.C.; Shova, S.; Silion, M.; Pinteala, M. Novel Antimicrobial Iodo-Dihydro-Pyrrole-2-One Compounds. Future Med. Chem. 2023, 15, 1369–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amărandi, R.-M.; Al-Matarneh, M.-C.; Popovici, L.; Ciobanu, C.I.; Neamțu, A.; Mangalagiu, I.I.; Danac, R. Exploring Pyrrolo-Fused Heterocycles as Promising Anticancer Agents: An Integrated Synthetic, Biological, and Computational Approach. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Rodríguez, M.; López-Rojas, P.; Amesty, Á.; Aranda-Tavío, H.; Brito-Casillas, Y.; Estévez-Braun, A.; Fernández-Pérez, L.; Guerra, B.; Recio, C. Discovery of Highly Functionalized 5-Hydroxy-2H-Pyrrol-2-Ones That Exhibit Antiestrogenic Effects in Breast and Endometrial Cancer Cells and Potentiate the Antitumoral Effect of Tamoxifen. Cancers 2022, 14, 5174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Matarneh, C.M.; Pinteala, M.; Nicolescu, A.; Silion, M.; Mocci, F.; Puf, R.; Angeli, A.; Ferraroni, M.; Supuran, C.T.; Zara, S.; et al. Synthetic Approaches to Novel Human Carbonic Anhydrase Isoform Inhibitors Based on Pyrrol-2-One Moiety. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 3018–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairoch, A. The Cellosaurus, a Cell-Line Knowledge Resource. J. Biomol. Tech. 2018, 29, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, H.R. The NCI60 human tumor cell line anticancer drug screen. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skehan, P.; Storeng, R.; Scudiero, D.; Monks, A.; McMahon, J.; Vistica, D.; Warren, J.T.; Bokesch, H.; Kenney, S.; Boyd, M.R. Newcolorimetric cytotoxicity assay for anticancer–drug screening. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1990, 82, 1107–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, R.B. The NCI in Vitro Anticancer Drug Discovery Screen. In Anticancer Drug Development Guide; Teicher, B.A., Ed.; Cancer Drug Discovery and Development; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 1997; pp. 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Cell Lines in the in Vitro Screen. Available online: https://dtp.cancer.gov/discovery_development/nci-60/cell_list.htm (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- The Standard NCI/DTP Methodology of the in Vitro Cancer Screen. Available online: https://dtp.cancer.gov/discovery_development/nci-60/methodology.htm (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Al-Matarneh, A.; Simionescu, N.; Nicolescu, A.; Cibotariu, N.; Danac, R.; Al-Matarneh, M.; Mangalagiu, I.I. Pyrrolo-Fused Phenanthridines as Potential Anticancer Agents: Synthesis, Prediction, and Biological Evaluation. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2025, 39, e70443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holbeck, S.L.; Collins, J.M.; Doroshow, J.H. Analysis of Food and Drug Administration—Approved Anticancer Agents in the NCI60 Panel of Human Tumor Cell Lines. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010, 9, 1451–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Smith, K.M.; Chong, A.L.; Stempak, D.; Yeger, H.; Marrano, P.; Kaplan, D.R.; Baruchel, S. In Vivo Antitumor and Antimetastatic Activity of Sunitinib in Preclinical Neuroblastoma Mouse Model 1. Neoplasia 2009, 11, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McTigue, M.; Deng, Y.; Ryan, K.; Brooun, A.; Diehl, W.; Stewart, A. Crystal Structure of Vegfr2 (Juxtamembrane and Kinase domains) in Complex with Sunitinib (SU11248) (N-2-Diethylaminoethyl)-5-((Z)-(5-Fluoro-2-Oxo-1H-Indol-3-Ylidene)Methyl)-2,4-Dimethyl-1H-Pyrrole-3-Carboxamide). Worldw. Protein Data Bank 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated Docking with Selective Receptor Flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Goodsell, D.S.; Halliday, R.S.; Huey, R.; Hart, W.E.; Belew, R.K.; Olson, A.J. Automated Docking Using a Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm and an Empirical Binding Free Energy Function. J. Comput. Chem. 1998, 19, 1639–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cmp | MW (g/mol) | LogP | Solubility | GI Absorption | BBB Permeant | Log Kp (Skin Permeation (cm/s) | Bioavailability | Synthetic Accessibility | Radar |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | 578.18 | 5.06 | Poorly soluble | High | Yes | −5.47 | 0.17 | 3.68 |  |

| 3b | 596.17 | 5.41 | −5.51 | 0.17 | 3.70 |  | |||

| 3c | 612.63 | 5.63 | −5.24 | 0.17 | 3.70 |  | |||

| 3d | 657.08 | 5.72 | −5.47 | 0.17 | 3.72 |  | |||

| 3e | 646.18 | 6.12 | Low | No | −5.26 | 0.17 | 3.81 |  | |

| 3f | 714.18 | 7.13 | Insoluble | −5.05 | 0.17 | 4.00 |  | ||

| 3g | 594.18 | 4.70 | Poorly soluble | High | Yes | −5.82 | 0.17 | 3.66 |  |

| 3h | 610.18 | 4.28 | −6.17 | 0.55 | 3.71 |  | |||

| 3i | 608.21 | 5.10 | −5.68 | 0.17 | 3.81 |  | |||

| 3j | 638.24 | 5.05 | −5.88 | 0.17 | 3.92 |  | |||

| 3k | 668.26 | 4.98 | −6.08 | 0.55 | 4.18 |  | |||

| 3l | 603.19 | 4.87 | −5.83 | 0.17 | 3.75 |  | |||

| 3m | 568.15 | 4.37 | −6.05 | 0.55 | 3.89 |  | |||

| 3n | 622.19 | 4.86 | −5.88 | 0.17 | 3.84 |  |

| Cell Type | Compound Cell Line | GI (%) (10–5 M) * | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | 3b | 3c | 3d | 3e | 3f | 3g | 3h | 3i | 3j | 3k | 3l | 3m | 3n | ||

| Leukemia | CCRF-CEM | 4 | 74 | 15 | 17 | 100 c | 100 p | 94 | 100 w | 0 | 0 | 0 | 74 | 59 | 3 |

| HL-60(TB) | 0 | 35 | 0 | 0 | 51 | 59 | 75 | 100 x | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 30 | 16 | |

| K-562 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 16 | 26 | 78 | 89 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 14 | 6 | |

| MOLT-4 | 2 | 66 | 29 | 20 | 75 | 89 | 100 t | 100 y | 17 | 0 | 0 | 78 | 70 | 20 | |

| RPMI-8226 | 100 a | 35 | 30 | 34 | 60 | 43 | 100 u | 100 z | 32 | 7 | 14 | 83 | 93 | 20 | |

| SR | 44 | 92 | 41 | 0 | 99 | 47 | 100 d | 100 a1 | 23 | 0 | 7 | 87 | 76 | 27 | |

| Non-small Cell Lung Cancer | A549/ATCC | 5 | 13 | 4 | 0 | 30 | 16 | 22 | 73 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 31 | 16 | 15 |

| EKVX | 37 | 24 | 37 | 36 | 100 d | 35 | 64 | 22 | 49 | 40 | 0 | 99 | 39 | 12 | |

| HOP-62 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5 | 82 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | 50 | 0 | |

| HOP-92 | 0 | 36 | 27 | 0 | 62 | 19 | 66 | 66 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 75 | 29 | 4 | |

| NCI-H226 | 4 | 4 | 62 | 17. | 100 e | 81 | 47 | 35 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 100 i1 | 22 | 3 | |

| NCI-H23 | 6 | 8 | 13 | 3 | 11 | 12 | 45 | 73 | 30 | 8 | 0 | 36 | 19 | 18 | |

| NCI-H322M | 17 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 97 | 10 | 20 | 34 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 51 | 19 | 3 | |

| NCI-H460 | 1 | 17 | 7 | 0 | 43 | 35 | 69 | 98 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 3 | |

| NCI-H522 | 50 | 26 | 24 | 2 | 53 | 34 | 70 | 82 | 37 | 0 | 2 | 32 | 31 | 26 | |

| Colon Cancer | COLO205 | 0 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 61 | 59 | 42 | 98 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 46 | 8 | 5 |

| HCC-2998 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 53 | 98 | 21 | 0 | 5 | 50 | 10 | 6 | |

| HCT-116 | 14 | 21 | 25 | 19 | 58 | 43 | 61 | 96 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 48 | 20 | 9 | |

| HCT-15 | 19 | 9 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 17 | 84 | 84 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 16 | 9 | |

| HT-29 | 0 | 16 | 19 | 14 | 32 | 5 | 96 | 96 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 6 | 5 | |

| KM12 | 8 | 26 | 17 | 17 | 35 | 13 | 80 | 100 b1 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 52 | 48 | 19 | |

| SW-620 | 0 | 24 | 12 | 16 | 47 | 20 | 56 | 100 c1 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 16 | 9 | |

| CNS Cancer | SF-268 | 16 | 68 | 24 | 15 | 100 f | 21 | 35 | 82 | 24 | 3 | 1 | 93 | 79 | 25 |

| SF-295 | 48 | 56 | 28 | 0 | 2 | 63 | 9 | ||||||||

| SF-539 | 12 | 51 | 11 | 0 | 37 | 17 | 69 | 72 | 31 | 28 | 18 | 35 | 63 | 87 | |

| SNB-19 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 71 | 19 | 17 | 69 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 8 | 5 | |

| SNB-75 | 15 | 100 b | 12 | 3 | 100 g | 100 q | 77 | 86 | 37 | 0 | 0 | 100 j1 | 9 | 20 | |

| U251 | 29 | 58 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Melanoma | LOX IMVI | 18 | 0 | 11 | 1 | 7 | 17 | 44 | 57 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 89 | 63 | 10 |

| MALME-3M | 0 | 6 | 17 | 0 | 78 | 0 | 83 | 100 d1 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 46 | 34 | 0 | |

| M14 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 64 | 0 | 52 | 99 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 63 | 4 | 5 | |

| MDA-MB-435 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 73 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 84 | 0 | |

| SK-MEL-2 | 26 | 31 | 43 | 16 | 100 h | 35 | 56 | 100 e1 | 44 | 0 | 0 | 100 k1 | 100 p1 | 56 | |

| SK-MEL-28 | 2 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 31 | 9 | 42 | 75 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 20 | 3 | |

| SK-MEL-5 | 1 | 5 | 18 | 20 | 0 | 12 | 27 | 94 | 4 | 11 | 12 | 24 | 17 | 1 | |

| UACC-257 | 13 | 8 | 23 | 3 | 100 i | 0 | 42 | 68 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 32 | 0 | |

| UACC-62 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 33 | 62 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 61 | 0 | |

| Ovarian Cancer | IGROV1 | 16 | 7 | 16 | 16 | 12 | 0 | 27 | 26 | 57 | 0 | 2 | 54 | 8 | 5 |

| OVCAR-3 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 5 | 72 | 35 | 59 | 96 | 46 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 8 | 10 | |

| OVCAR-4 | 20 | 38 | 34 | 30 | 100 j | 69 | 85 | 100 f1 | 60 | 0 | 3 | 100 l1 | 0 | 14 | |

| OVCAR-5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 9 | 24 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | |

| OVCAR-8 | 15 | 8 | 11 | 0 | 43 | 26 | 31 | 37 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 11 | 0 | |

| NCI/ADR-RES | 0 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 35 | 7 | 44 | 35 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 15 | 0 | |

| SK-OV-3 | 8 | 12 | 13 | 0 | 50 | 10 | 25 | 64 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 75 | 67 | 13 | |

| Renal cancer | 786-0 | 17 | 27 | 18 | 6 | 76 | 29 | 52 | 0 | 3 | 55 | 36 | 9 | ||

| A498 | 16 | 21 | 19 | 5 | 100 k | 90 | 48 | 61 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 88 | 12 | 16 | |

| ACHN | 13 | 35 | 21 | 15 | 100 l | 49 | 61 | 0 | 0 | 100 m1 | 9 | 0 | |||

| CAKI-1 | 3 | 13 | 19 | 12 | 91 | 32 | 41 | 44 | 28 | 5 | 15 | 62 | 53 | 16 | |

| SN12C | 23 | 28 | 25 | 15 | 60 | 61 | 60 | 100 g1 | 20 | 0 | 2 | 59 | 27 | 16 | |

| TK-10 | 12 | 27 | 1 | 0 | 100 m | 57 | 43 | 50 | 30 | 0 | 1 | 99 | 7 | 0 | |

| UO-31 | 54 | 54 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 6 | ||||||||

| Prostate cancer | PC-3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 26 | 25 | 73 | 71 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 45 | 28 | 1 |

| DU-145 | 0 | 9 | 10 | 0 | 28 | 5 | 58 | 40 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 0 | 0 | |

| Breast cancer | MCF7 | 44 | 56 | 47 | 60 | 44 | 46 | 83 | 91 | 50 | 6 | 23 | 52 | 93 | 30 |

| MDA-MB-231/ATCC | 0 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 62 | 42 | 44 | 42 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 100 n1 | 11 | 0 | |

| HS 578T | 71 | 90 | 55 | 41 | 100 n | 100 r | 100 v | 63 | 84 | 0 | 0 | 100 o1 | 39 | 25 | |

| BT-549 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 54 | 81 | 2 | 0 | 10 | - | 17 | 3 | |

| T-47D | 34 | 32 | 48 | 49 | 100 o | 100 s | 80 | 65 | 39 | 6 | 8 | 59 | 49 | 22 | |

| MDA-MB-468 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 96 | 100 h1 | 43 | 22 | 44 | - | 100 q1 | 83 | |

| Cell Type | Compound Cell Line ↓ | 3e | 3h | 3l | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GI50 (μM) | TGI (μM) | LC50 (μM) | GI50 (μM) | TGI (μM) | LC50 (μM) | GI50 (μM) | TGI (μM) | LC50 (μM) | ||

| Leukemia | HL-60(TB) | 4.48 | >100 | >100 | 2.19 | 4.28 | 8.38 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| SR | 2.84 | >100 | >100 | 1.55 | 2.99 | 5.75 | 6.28 | >100 | >100 | |

| CCRF-CEM | 3.35 | >100 | >100 | 3.09 | >100 | 3.61 | 3.26 | >100 | >100 | |

| MOLT-4 | 2.92 | >100 | >100 | 2.08 | 4.17 | 8.35 | 2.11 | >100 | >100 | |

| RPMI-8226 | 5.38 | >100 | >100 | 2.40 | 6.01 | >100 | 3.07 | >100 | >100 | |

| Non-small Cell Lung Cancer | NCI-H226 | 8.48 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 4.42 | >100 | >100 |

| HOP-92 | 3.15 | 7.22 | >100 | 4.08 | 8.97 | >100 | 1.46 | 4.89 | >100 | |

| A549/ATCC | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 8.08 | >100 | >100 | |

| HOP-62 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 5.21 | >100 | >100 | |

| Colon Cancer | HT29 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 8.80 | >100 | >100 | 9.43 | >100 | >100 |

| SW-620 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 5.91 | >100 | >100 | |

| KM12 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 5.22 | >100 | >100 | 9.70 | >100 | >100 | |

| HCT-116 | 5.92 | >100 | >100 | 7.43 | >100 | >100 | 3.83 | >100 | >100 | |

| COLO 205 | 4.57 | >100 | >100 | 6.65 | >100 | >100 | 5.29 | >100 | >100 | |

| CNS Cancer | SF-268 | 4.66 | >100 | >100 | 6.04 | >100 | >100 | 4.69 | >100 | >100 |

| SNB-75 | 2.60 | 5.06 | 9.85 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 1.34 | 3.42 | 8.76 | |

| U251 | 8.97 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 4.17 | >100 | >100 | |

| Melanoma | MALME-3M | 2.00 | 4.32 | 9.34 | 2.68 | >100 | >100 | 2.07 | >100 | >100 |

| M14 | 8.94 | >100 | >100 | 5.34 | >100 | >100 | 7.24 | >100 | >100 | |

| SK-MEL-2 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 6.64 | >100 | >100 | 3.70 | >100 | >100 | |

| LOX IMVI | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 3.38 | >100 | >100 | |

| Ovarian Cancer | OVCAR-3 | 7.48 | >100 | >100 | 9.16 | >100 | >100 | 4.72 | >100 | >100 |

| OVCAR-4 | 1.82 | 4.41 | >100 | 3.27 | >100 | >100 | 0.422 | 1.69 | 4.82 | |

| IGROV1 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 8.67 | >100 | >100 | |

| SK-OV-3 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 7.60 | >100 | >100 | 6.41 | >100 | >100 | |

| Renal Cancer | CAKI-1 | 3.72 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 9.48 | >100 | >100 |

| A498 | 1.95 | 3.56 | 6.50 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 2.99 | >100 | >100 | |

| ACHN | 4.05 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 5.36 | >100 | >100 | |

| RXF 393 | 4.23 | >100 | >100 | 6.25 | >100 | >100 | 3.72 | >100 | >100 | |

| TK-10 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 3.85 | >100 | >100 | |

| Breast cancer | MDA-MB-231/ATCC | 5.36 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 2.50 | 9.63 | >100 |

| HS 578T | 3.45 | 9.97 | >100 | 6.65 | >100 | >100 | 2.10 | 5.64 | >100 | |

| BT-549 | 9.61 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 5.81 | >100 | >100 | |

| T-47D | 2.74 | 7.57 | >100 | 2.41 | >100 | >100 | 7.13 | >100 | >100 | |

| MDA-MB-468 | 3.24 | >100 | >100 | 3.10 | >100 | >100 | 2.70 | >100 | >100 | |

| Prostate cancer | PC-3 | 9.99 | >100 | >100 | 8.83 | >100 | >100 | 2.40 | >100 | >100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Simionescu, N.; Al-Matarneh, A.; Mangalagiu, I.I.; Cibotariu, N.; Uritu, C.M.; Al-Matarneh, C.M.; Pinteala, M. Reinvestigating Pyrrol-2-One-Based Compounds: From Antimicrobial Agents to Promising Antitumor Candidates. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1813. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121813

Simionescu N, Al-Matarneh A, Mangalagiu II, Cibotariu N, Uritu CM, Al-Matarneh CM, Pinteala M. Reinvestigating Pyrrol-2-One-Based Compounds: From Antimicrobial Agents to Promising Antitumor Candidates. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1813. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121813

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimionescu, Natalia, Ashraf Al-Matarneh, Ionel I. Mangalagiu, Narcis Cibotariu, Cristina Mariana Uritu, Cristina Maria Al-Matarneh, and Mariana Pinteala. 2025. "Reinvestigating Pyrrol-2-One-Based Compounds: From Antimicrobial Agents to Promising Antitumor Candidates" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1813. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121813

APA StyleSimionescu, N., Al-Matarneh, A., Mangalagiu, I. I., Cibotariu, N., Uritu, C. M., Al-Matarneh, C. M., & Pinteala, M. (2025). Reinvestigating Pyrrol-2-One-Based Compounds: From Antimicrobial Agents to Promising Antitumor Candidates. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1813. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121813