Docking in the Dark: Insights into Protein–Protein and Protein–Ligand Blind Docking

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Classical Blind Docking

1.2. Machine Learning (ML)-Based Blind Docking

1.3. Focus of This Review

2. Protein–Protein and Protein–Peptide Blind Docking

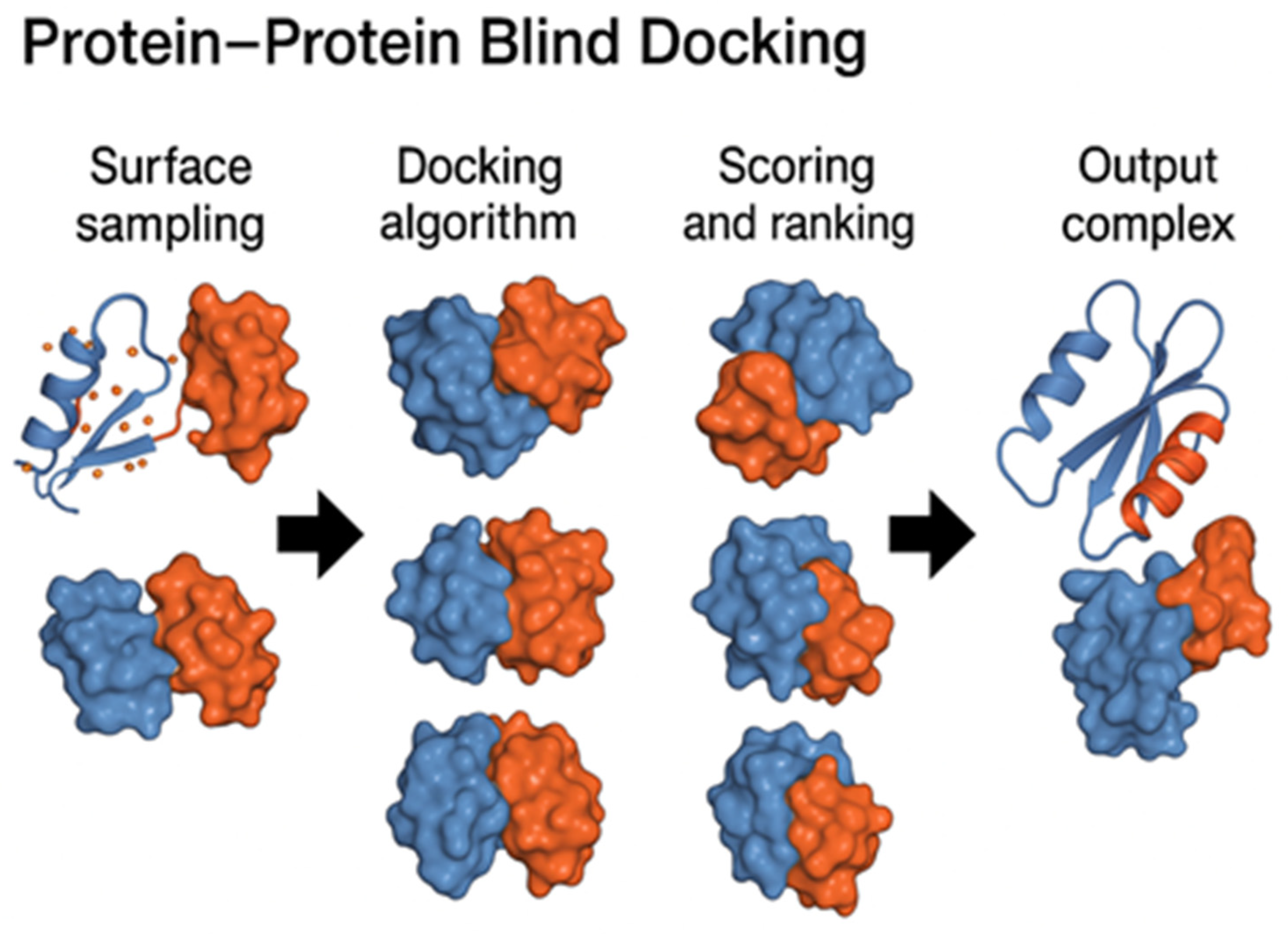

2.1. Protein–Protein Blind Docking

2.1.1. Early Rigid-Body and Geometry-Based Approaches (2001–2005)

2.1.2. Transition to Energy-Based and Reduced-Representation Models (2005–2010)

| Study (Year) | Docking Method | Working Principle | Performance & Key Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ritchie (2003, 2013) [25,26] | Hex | Spherical polar Fourier (SPF) correlation to accelerate calculation | Good results in CAPRI Rounds 1, 2, 3, 5 | No more development after 2013 |

| Weng et al. (2003) [27] | ZDOCK | New scoring functions | 90% accuracy out of 44 test cases | Not reported |

| Schneidman-Duhovny et al. (2005) [29] | PatchDock | Connolly complementary patches and transformation | High efficiency for fast transformational search | 100 solutions at most |

| Schneidman-Duhovny et al. (2005) [29] | SymmDock | Like PatchDock, but limited to symmetric cyclic transformation | High efficiency for fast transformational search | 100 solutions at most |

| Zacharias (2005) [30] | ATTRACT | Representation of e-pseudoatoms per residue, multicopy strategy conformational analysis | 3 out of 5 CAPRI target RMSD < 1.8 Å | Inaccuracies for extensive backbone conformational changes |

| Garzon et al. (2009) [31] | FRODOCK | 3D grid-based potentials with the efficiency of spherical harmonics approximations | In 4 out of 9 of the CAPRI test cases, the method predicted at least one acceptable solution within the top 10 | Slower than PatchDock |

| de Vries & Bonvin (2011) [33] | CPORT-HADDOCK (Interface prediction + blind docking) | Combined six predictors and docking for refinement | Better than ZDOCK-ZRANK; improved after post-docking analysis | Requires interface prediction first |

| Torchala et al. (2013) [34] | SwarmDock—CAPRI | 176 cases—Generates low energy poses and ranks them | 71.6% all poses; 36.4% top 10 poses | Lower accuracy on large proteins |

| Lensink et al. (2019) [35] | CAPRI round 46 | Evaluated automated predictions | High accuracy on easy target; only three models have good quality | Easy and difficult targets create a significant performance gap. Residues in protein binding interfaces were less well-predicted than in previous CAPRi rounds |

| Harmalkar & Gray (2021) [36] | Comparison of enhanced docking methods | Used MD, Monte Carlo, ML for flexibility | Notable improvement in COVID and Alzheimer targets | Conformational change prediction remains hard |

| Che et al. (2022) [12] | AutoDock Vina | ML-enhanced blind docking: uses ANN to identify true binding sites | 88.6% (top-n); 95.6% (top n + 2) for LBS (ligand binding site prediction | Still needs improvement in speed |

2.1.3. Emergence of Data-Driven and Hybrid Docking Strategies (2010–2015)

2.1.4. Integration of ML and AI-Enhanced Docking (2016–2022)

2.1.5. Future Directions and Remaining Challenges

2.2. Protein-Peptide Blind Docking

| Study (Year) | Docking Method | Working Principle | Performance & Key Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antes (2010) [37] | DynaDock | Two-step algorithm with OPMD (optimized potential molecular dynamics] | 11/15 best scoring poses featured a peptide RMSD < 2.0 Å | Time-consuming with respect to the hardware in 2010 |

| Raveh et al. (2011) [38] | Rosetta FexPepDock | Ab initio modeling and coarse-grained representation | 18/26 cases in bound form; 7/14 cases in unbound form Perform well on various classes of secondary structure | Computational intensive |

| Trellet et al. (2013) [39] | HADDOCK | Ensemble, flexible docking | high quality models: 79,4% bound/unbound; 69,4% unbound/unbound 18% better accuracy than FlexPepDock | Not able to model no-helical datasets |

| Song et al. (2014) [40] | Autodock | Two-step dipeptide blind docking (400 dipeptides), | Dipeptides are used as protein functional site recognizers. Potential role in detecting immunactive sites | limited benchmark on two proteins: human fibroblast growth factor-2 (h-FGF2) and scorpion toxin protein (BmkM1) |

| Saladin et al. (2014) [41] | PEP-SiteFinder | Scans the full protein surface with peptide conformations | 90% accuracy on 41 complexes Creation of the Propensity Index | Long computation time (30–60 min) for each structure. Limited to peptides with a maximum of 30 residues |

| Ben-Shimon et al. (2015) [42] | AnchorDock | Identifies anchoring spots and uses SA-MD for refinement | RMSD ≤ 2.2 Å; high accuracy (10 out of 13 unbound cases tested) | Relies on anchoring prediction accuracy |

| Schindler et al. (2015) [43] | pepATTRACT | Coarse-grained + flexible refinement Scans protein surface, then atomistic refinement | 70% success without prior site info | Could benefit from ML integration |

| Yan et al. (2016) [44] | MDOCKPeP | Global docking of all-atom flexible peptide on PeptiDB | 95–92.2% success (bound/unbound) | Needs flexibility modeling |

| Agrawal et al. (2018) [45] | Benchmark study: ZDOCK, FRODOCK, Hex, PatchDock, ATTRACT, and PepATTRACT | Tested six methods on 133 complexes | FRODOCK best (blind); ZDOCK best (re-docking) | Ranking methods need improvement |

| Zhou et al. (2018) [16] | HPEPDOCK | Peptide flexibility through an ensemble of conformations | 33.3% (global); 72.6% (local); 29.8 min runtime | Needs model refinement |

| Balint et al. (2019) [46] | Fragment-based blind docking | Split peptide and reassembled in complex | Correct placement of anchoring fragments | Simple force fields; no water model C-terminal weakly identified |

| Khramushin et al. (2022) [47] | PatchMan | Receptor-centric docking using motifs | 58% ≤ 2.5 Å; 84% ≤ 5 Å RMSD; 100% sampling | Closed pockets |

3. Ligand-Protein Blind Docking

| Study (Year) | Docking Method | Working Principle | Performance & Key Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ritchie (2003, 2013) [25,26] | Hex | spherical polar Fourier (SPF) correlation to accelerate calculation | Good results in CAPRI Rounds 1, 2, 3, 5 | No more development after 2013 |

| Schneidman-Duhovny et al. (2005) [29] | PatchDock | Connolly complementary patches and transformation | High efficiency for fast transformational search | 100 solutions at most |

| Schneidman-Duhovny et al. (2005) [29] | SymmDock | Like PatchDock, but limited to symmetric cyclic transformation | High efficiency for fast transformational search | 100 solutions at most |

| Hetenyi et al. (2006) [24] | Autodock | Drug-sized compounds and proteins up to 1000 residues | Performed well on the system with moderate flexibility | May prove insufficient for systems with a higher degree of induced fit upon ligand binding |

| Ghersi & Sanchez (2009) [48] | Focused docking | Predict the binding sites, reducing the search space in focused regions | Improved speed and accuracy; useful for reverse screening | Not applicable to global search |

| Grosdidier et al. (2009) [23] | EADock 2.0 | Improved blind and local docking with new seeding and scoring | 65–76% (blind), 75–83% (local) success on 260 structures | Sensitive to structure quality; lacks metal interaction handling |

| Hetényi et al. (2011) [49] | Blind docking + pocket search | Analyzed ligand-free proteins & hydration effect | Performed well on complex cases | Limitations due to multiple pockets |

| Lee and Zhang (2011) [50] | BSP-SLIM | Template-based blind docking for low-resolution models | RMSD 3.99 Å; better than Autodock and LIGSITE; 25–50% enrichment | Needs improved ligand flexibility modeling |

| Grosdidier et al. (2011) [51] | SwissDock | Web server based on the engine EADock | 251 test complexes: 77% correct Binding Mode | Depends on the number of rotatable bonds of the ligands |

| Sánchez-Linares et al. (2012) [52] | BINDSURF | GPU-based scan of the whole protein for multiple binding sites | Rapid screening and accurate site prediction for repurposing | Not mentioned |

| Labbé et al. (2015) [15] | MTIOpen Autodock 4.2 | Blind docking and screening via MTiAu-toDock and MTi-OpenScreen | Docked 24/27 proteins accurately; 80% VS ac-curacy | Not mentioned |

| Saadi et al. (2017) [18] | Parallel blind docking | Used GPU acceleration for large-scale targets | 225x/62x faster than CPU; large dataset support | Accuracy of the desolvation energy needs improvement |

| Pérez-Sánchez et al. (2017) [21] and (2021) [20] | Blind Docking (HPC) | Full surface scanning with HPC; business-oriented | Good industrial potential; positive feedback. Used to identify influenza virus polymerase inhibitors | Data privacy concerns for cloud systems |

| Sharmar et al. (2018) [54] | AutoDock Vina Blind Docking | Examined exhaustiveness settings on FXa targets | Higher values improved accuracy but reduced speed | Needs parameter optimization and validation |

| Liu et al. (2019) [17] | CB-Dock | Cavity-based binding site prediction + AutoDock Vina | 70% success; better than traditional tools Applied by Ranade et al. (2023) [14] to Dengue Virus protease inhibitors | High computational cost; weak apo performance |

| Liao et al. (2019) [61] | DeepDock | Universal deep neural network method | Outperform > 4% competing methods | NA |

| Zhang et al. (2020) [58] | EDock | REMC-based with no prior info or high-res input | RMSD 2.03 Å; better than Dock6/Vina; 67% success | Long run times (~2 h); high resource demand |

| Guedes et al. (2021) [11] | DockTScore | Scoring functions via ML and physics-based descriptors | Strong results on DUD-E for affinity prediction and VS | Struggles with diverse protein classes |

| Mohammad et al. (2021) [59] | InstaDock | GUI-based AutoDock Vina (Quick Vina-W) tool | Easy for beginners; large-scale screening is enabled | Lacks ADMET/QSAR, planned for future updates |

| Jofily et al. (2021) [9] | BLinDPyPr | Combines blind and cavity-guided docking using DOCK6 and FTMap | Achieved 45.2–54.3% pose prediction; 2x faster than traditional DOCK6 blind docking | Needs a GUI/web version; lacks scoring refinement |

| Grasso et al. (2022) [60] | FRAD | Docking with MM/GBSA re-scoring for pose accuracy | Better performance than traditional docking on >300 complexes | Needs ML integration for larger datasets |

| Stärk et al. (2022) [62] | EQUIBIND | An SE(3)-equivariant geometric DL model | Better performance than traditional docking methods | Only implicitly models the atom positions of side chains |

| Lu et al. (2022) [63] | TANKBIND | Trigonometry constraint as a vigorous inductive bias into the model, all possible binding sites | Outperform EQUIBIND, 22% increase in the fraction of prediction below 5 Å; 42% increase with proteins out of the training set | NA |

| Corso et al. (2023) [64] | DiffDock | Diffusion generative model over the non-Euclidean manifold of ligand poses | Outperform TANKBIND and EQUIBIND with high selective accuracy | NA |

| Huang et al. (2023) [10] | DSDP | ML-based site prediction + AutoDock Vina pose sampling | 29.8% top-1 success rate (1.2 s/run); 57.2% (DUD-E), 41.8% (PDBBind) success rates | Needs improved scoring functions |

| Yu et al. (2023) [13] | Hybrid: DL + Traditional | DL for site prediction, traditional for ligand docking | DL excels in site prediction; traditional docking is better for pose accuracy | Blind docking alone is unreliable; a hybrid suggested |

| Zhang et al. (2022) [65] | E3Bind | Equivariant DL model refining ligand pose iteratively | Outperforms traditional and DL tools in docking accuracy | High computational cost; needs diverse datasets |

| Buttenschoen et al. (2024) [66] | PoseBusters (evaluation tool) | Evaluates docking poses using chemical/physical plausibility | Found conventional tools outperform DL methods on physical accuracy | DL methods fail to match physical realism despite low RMSD |

| Ugurlu et al. (2024) [8] | CoBDock | Consensus-based blind docking using multi-tool + ML pipeline | Binding site prediction accuracy 0.50–0.88; pose RMSD < 2 Å in 40–67% cases; outperforms other tools | Modular improvements needed for large-scale use |

4. Conclusions and Future Perspective

4.1. Advances

4.2. Challenges

4.3. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sahu, M.K.; Nayak, A.K.; Hailemeskel, B.; Eyupoglu, O.E. Exploring Recent Updates on Molecular Docking: Types, Method, Application, Limitation & Future Prospects. Int. J. Pharm. Res. Allied Sci. 2024, 13, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klebe, G. Protein Modeling and Structure-Based Drug Design. In Drug Design: From Structure and Mode-of-Action to Rational Design Concepts; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 309–321. [Google Scholar]

- de Angelo, R.M.; de Sousa, D.S.; da Silva, A.P.; Chiari, L.P.A.; da Silva, A.B.F.; Honorio, K.M. Molecular Docking: State-of-the-Art Scoring Functions and Search Algorithms. In Computer-Aided and ML-Driven Drug Design: From Theory to Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 163–198. [Google Scholar]

- Jilla, T. The Role of Molecular Docking in Drug Discovery: Current Approaches and Innovations. Int. J. Zool. Environ. Life Sci. 2025, 21, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammed, M.T.; Aki-Yalcin, E. Molecular Docking: Principles, Advances, and Its Applications in Drug Discovery. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 2024, 21, 480–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S.S.; Niranjan, V.; Bandikatte, S.A.; Govindappa, S.; Vishal, A. Structure-Based Drug Discovery. In Molecular Modeling and Docking Techniques for Drug Discovery and Design; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 435–472. [Google Scholar]

- Culletta, G.; Almerico, A.M.; Tutone, M. Comparing Molecular Dynamics-Derived Pharmacophore Models with Docking: A Study on CDK-2 Inhibitors. Chem. Data Collect. 2020, 28, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugurlu, S.Y.; McDonald, D.; Lei, H.; Jones, A.M.; Li, S.; Tong, H.Y.; Butler, M.S.; He, S. Cobdock: An Accurate and Practical ML-Based Consensus Blind Docking Method. J. Cheminform. 2024, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jofily, P.; Pascutti, P.G.; Torres, P.H.M. Improving Blind Docking in DOCK6 through an Automated Preliminary Fragment ff Probing Strategy. Molecules 2021, 26, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, S.; Yue, D.; Lin, X.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Y.Q. Dsdp: A Blind Docking Strategy Accelerated by Gpus. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 4355–4363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, I.A.; Barreto, A.M.S.; Marinho, D.; Krempser, E.; Kuenemann, M.A.; Sperandio, O.; Dardenne, L.E.; Miteva, M.A. New ML and Physics-Based Scoring Functions for Drug Discovery. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, X.; Chai, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L. Prediction of Ligand Binding Sites Using Improved Blind Docking Method with a ML-Based Scoring Function. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 261, 117962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Lu, S.; Gao, Z.; Zheng, H.; Ke, G. Do DL Models Really Outperform Traditional Approaches in Molecular Docking? arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.07134. [Google Scholar]

- Ranade, P.B.; Navale, D.N.; Zote, S.W.; Kulal, D.K.; Wagh, S.J. Blind Docking of 4-Amino-7-Chloroquinoline Analogs as Potential Dengue Virus Protease Inhibitor Using CB Dock a Web Server. Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. 2023, 60, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labbé, C.M.; Rey, J.; Lagorce, D.; Vavruša, M.; Becot, J.; Sperandio, O.; Villoutreix, B.O.; Tufféry, P.; Miteva, M.A. MTiOpenScreen: A Web Server for Structure-Based Virtual Screening. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W448–W454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Jin, B.; Li, H.; Huang, S.-Y. HPEPDOCK: A Web Server for Blind Peptide–Protein Docking Based on a Hierarchical Algorithm. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W443–W450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Grimm, M.; Dai, W.; Hou, M.; Xiao, Z.-X.; Cao, Y. CB-Dock: A Web Server for Cavity Detection-Guided Protein–Ligand Blind Docking. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 41, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadi, H.; Nouali-Taboudjemat, N.; Rahmoun, A.; Imbernón, B.; Pérez-Sánchez, H.; Cecilia, J.M. Parallel Desolvation Energy Term Calculation for Blind Docking on GPU Architectures. In Proceedings of the 2017 46th International Conference on Parallel Processing Workshops (ICPPW), Bristol, UK, 14–17 August 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, N.M.; Alhossary, A.A.; Mu, Y.; Kwoh, C.-K. Protein-Ligand Blind Docking Using QuickVina-W with Inter-Process Spatio-Temporal Integration. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Sanchez, H.; Kumar, D.T.; Doss, C.G.P.; Rodríguez-Schmidt, R.; Cerón-Carrasco, J.P.; Peña-García, J.; Ye, Z.-W.; Yuan, S.; Günther, S. Prediction and Characterization of Influenza Virus Polymerase Inhibitors through Blind Docking and Ligand-Based Virtual Screening. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 321, 114784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sánchez, H.; Cerón-Carrasco, J.P.; Cecilia, J.M. Implementation of an Efficient Blind Docking Technique on HPC Architectures for the Discovery of Allosteric Inhibitors. In Proceedings of the 2017 46th International Conference on Parallel Processing Workshops (ICPPW), Bristol, UK, 14–17 August 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Cerón-Carrasco, J.P.; Cerezo, J.; Zuniga, J.; Requena, A.; Contreras-Garcia, J.; Chavan, S.; Manrubia-Cobo, M.; Imbernón, B.; Cecilia, J.M.; Sánchez, H.E.P. Application of Parallel Blind Docking with BINDSURF for the Study of Platinum Derived Compounds as Anticancer Drugs. In Proceedings of the IWBBIO, Granada, Spain, 7–9 April 2014; pp. 972–976. [Google Scholar]

- Grosdidier, A.; Zoete, V.; Michielin, O. Blind Docking of 260 Protein–Ligand Complexes with EADock 2.0. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2021–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetényi, C.; van der Spoel, D. Blind Docking of Drug-Sized Compounds to Proteins with up to a Thousand Residues. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 1447–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, D.W. Evaluation of protein docking predictions using Hex 3.1 in CAPRI rounds 1 and 2. Proteins 2003, 52, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoorah, A.W.; Devignes, M.-D.; Smaïl-Tabbone, M.; Ritchie, D.W. Protein docking using case-based reasoning. Proteins 2013, 81, 2150–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Li, L.; Weng, Z. ZDOCK: An initial-stage protein-docking algorithm. Proteins 2003, 52, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, B.G.; Wiehe, K.; Hwang, H.; Kim, B.-Y.; Vreven, T.; Weng, Z. ZDOCK server: Interactive docking prediction of protein–protein complexes and symmetric multimers. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1771–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneidman-Duhovny, D.; Inbar, Y.; Nussinov, R.; Wolfson, H.J. PatchDock and SymmDock: Servers for rigid and symmetric docking. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33 (Suppl. 2), W363–W367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zacharias, M. ATTRACT: Protein-protein docking in CAPRI using a reduced protein model. Proteins 2005, 60, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garzon, J.I.; Lopéz-Blanco, J.R.; Pons, C.; Kovacs, J.; Abagyan, R.; Fernandez-Recio, J.; Chacon, P. FRODOCK: A new approach for fast rotational protein–protein docking. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2544–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Aportela, E.; López-Blanco, J.R.; Chacón, P. FRODOCK 2.0: Fast protein–protein docking server. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 2386–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, S.J.; Bonvin, A.M.J.J. CPORT: A Consensus Interface Predictor and Its Performance in Prediction-Driven Docking with HADDOCK. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torchala, M.; Moal, I.H.; Chaleil, R.A.G.; Fernandez-Recio, J.; Bates, P.A. SwarmDock: A Server for Flexible Protein–Protein Docking. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 807–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lensink, M.F.; Brysbaert, G.; Nadzirin, N.; Velankar, S.; Chaleil, R.A.G.; Gerguri, T.; Bates, P.A.; Laine, E.; Carbone, A.; Grudinin, S. Blind Prediction of Homo-and Hetero-protein Complexes: The CASP13-CAPRI Experiment. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2019, 87, 1200–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmalkar, A.; Gray, J.J. Advances to Tackle Backbone Flexibility in Protein Docking. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2021, 67, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antes, I. DynaDock: A new molecular dynamics-based algorithm for protein-peptide docking including receptor flexibility. Proteins 2010, 78, 1084–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raveh, B.; London, N.; Zimmerman, L.; Schueler-Furman, O. Rosetta FlexPepDock ab-initio: Simultaneous Folding, Docking and Refinement of Peptides onto Their Receptors. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e18934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trellet, M.; Melquiond, A.S.J.; Bonvin, A.M.J.J. A Unified Conformational Selection and Induced Fit Approach to Protein-Peptide Docking. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.-H.; Yang, B.; Lu, F.-Y.; Li, C.-L.; Zhang, J.-H.; Song, Y.-B. A Molecular Modeling Method for Protein Functional Site Recognition with Dipeptide Blind Docking. Gene Ther. Mol. Biol. 2014, 16, 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Saladin, A.; Rey, J.; Thévenet, P.; Zacharias, M.; Moroy, G.; Tufféry, P. PEP-SiteFinder: A Tool for the Blind Identification of Peptide Binding Sites on Protein Surfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, W221–W226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Shimon, A.; Niv, M.Y. AnchorDock: Blind and Flexible Anchor-Driven Peptide Docking. Structure 2015, 23, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, C.E.M.; de Vries, S.J.; Zacharias, M. Fully Blind Peptide-Protein Docking with PepATTRACT. Structure 2015, 23, 1507–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Xu, X.; Zou, X. Fully Blind Docking at the Atomic Level for Protein-Peptide Complex Structure Prediction. Structure 2016, 24, 1842–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, P.; Singh, H.; Srivastava, H.K.; Singh, S.; Kishore, G.; Raghava, G.P.S. Benchmarking of Different Molecular Docking Methods for Protein-Peptide Docking. BMC Bioinform. 2019, 19, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bálint, M.; Horváth, I.; Mészáros, N.; Hetényi, C. Towards Unraveling the Histone Code by Fragment Blind Docking. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khramushin, A.; Ben-Aharon, Z.; Tsaban, T.; Varga, J.K.; Avraham, O.; Schueler-Furman, O. Matching Protein Surface Structural Patches for High-Resolution Blind Peptide Docking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2121153119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghersi, D.; Sanchez, R. Improving Accuracy and Efficiency of Blind Protein-Ligand Docking by Focusing on Predicted Binding Sites. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2009, 74, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetényi, C.; Spoel, D. van der Toward Prediction of Functional Protein Pockets Using Blind Docking and Pocket Search Algorithms. Protein Sci. 2011, 20, 880–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Zhang, Y. BSP-SLIM: A Blind Low-resolution Ligand-protein Docking Approach Using Predicted Protein Structures. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2012, 80, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosdidier, A.; Zoete, V.; Michielin, O. SwissDock, a protein-small molecule docking web service based on EADock DSS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, W270–W277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Linares, I.; Pérez-Sánchez, H.; Cecilia, J.M.; García, J.M. High-Throughput Parallel Blind Virtual Screening Using BINDSURF. BMC Bioinform. 2012, 13, S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carollo, P.S.; Tutone, M.; Culletta, G.; Fiduccia, I.; Corrao, F.; Pibiri, I.; Di Leonardo, A.; Zizzo, M.G.; Melfi, R.; Pace, A.; et al. Investigating the Inhibition of FTSJ1, a Tryptophan TRNA-Specific 2′-O-Methyltransferase by NV TRIDs, as a Mechanism of Readthrough in Nonsense Mutated CFTR. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmar, S.; Garg, I.; Kumar, B.; Ashraf, M.Z. Comparative Analysis of Blind Docking Reproducibility. Res. J. Life Sci. Bioinform. Pharm. Chem. Sci. 2018, 4, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Muzio, E.; Toti, D.; Polticelli, F. DockingApp: A user-friendly interface for facilitated docking simulations with AutoDock Vina. J. Comput. Mol. Des. 2017, 31, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Carmona, S.; Alvarez-Garcia, D.; Foloppe, N.; Garmendia-Doval, A.B.; Juhos, S.; Schmidtke, P.; Barril, X.; Hubbard, R.E.; Morley, S.D. rDock: A Fast, Versatile and Open Source Program for Docking Ligands to Proteins and Nucleic Acids. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014, 10, e1003571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugnon, M.; Röhrig, U.F.; Goullieux, M.; Perez, M.A.S.; Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissDock 2024: Major enhancements for small-molecule docking with Attracting Cavities and AutoDock Vina. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W324–W332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Bell, E.W.; Yin, M.; Zhang, Y. EDock: Blind Protein–Ligand Docking by Replica-Exchange Monte Carlo Simulation. J. Cheminform. 2020, 12, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammad, T.; Mathur, Y.; Hassan, M.I. InstaDock: A Single-Click Graphical User Interface for Molecular Docking-Based Virtual High-Throughput Screening. Brief Bioinform. 2021, 22, bbaa279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grasso, G.; Di Gregorio, A.; Mavkov, B.; Piga, D.; Labate, G.F.D.; Danani, A.; Deriu, M.A. Fragmented Blind Docking: A Novel Protein–Ligand Binding Prediction Protocol. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 40, 13472–13481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; You, R.; Huang, X.; Yao, X.; Huang, T.; Zhu, S. DeepDock: Enhancing Ligand-protein Interaction Prediction by a Combination of Ligand and Structure Information. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), San Diego, CA, USA, 18–21 November 2019; pp. 311–317. [Google Scholar]

- Stärk, H.; Ganea, O.-E.; Pattanaik, L.; Barzilay, R.; Jaakkola, T. EquiBind: Geometric DL for Drug Binding Structure Prediction. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.05146. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Rao, J.; Li, C.; Zheng, S. TANKBind: Trigonometry-Aware Neural NetworKs for Drug-Protein Binding Structure Prediction. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, G.; Stärk, H.; Jing, B.; Barzilay, R.; Jaakkola, T. DiffDock: Diffusion Steps, Twists, and Turns for Molecular Docking. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.01776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cai, H.; Shi, C.; Zhong, B.; Tang, J. E3bind: An End-to-End Equivariant Network for Protein-Ligand Docking. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.06069. [Google Scholar]

- Buttenschoen, M.; Morris, G.M.; Deane, C.M. PoseBusters: AI-Based Docking Methods Fail to Generate Physically Valid Poses or Generalise to Novel Sequences. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 3130–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.E.; Zhang, Y. Can DL Blind Docking Methods be Used to Predict Allosteric Compounds? J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025, 65, 3737–3748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, X.; Zhang, L. Blind docking methods have been inappropriately used in most network pharmacology analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1566772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roomi, M.S.; Culletta, G.; Longo, L.; Filgueira de Azevedo, W., Jr.; Perricone, U.; Tutone, M. Docking in the Dark: Insights into Protein–Protein and Protein–Ligand Blind Docking. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1777. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121777

Roomi MS, Culletta G, Longo L, Filgueira de Azevedo W Jr., Perricone U, Tutone M. Docking in the Dark: Insights into Protein–Protein and Protein–Ligand Blind Docking. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1777. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121777

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoomi, Muhammad Sohaib, Giulia Culletta, Lisa Longo, Walter Filgueira de Azevedo, Jr., Ugo Perricone, and Marco Tutone. 2025. "Docking in the Dark: Insights into Protein–Protein and Protein–Ligand Blind Docking" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1777. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121777

APA StyleRoomi, M. S., Culletta, G., Longo, L., Filgueira de Azevedo, W., Jr., Perricone, U., & Tutone, M. (2025). Docking in the Dark: Insights into Protein–Protein and Protein–Ligand Blind Docking. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1777. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121777