Recent Advances in the Biological Activity of s-Triazine Core Compounds

Abstract

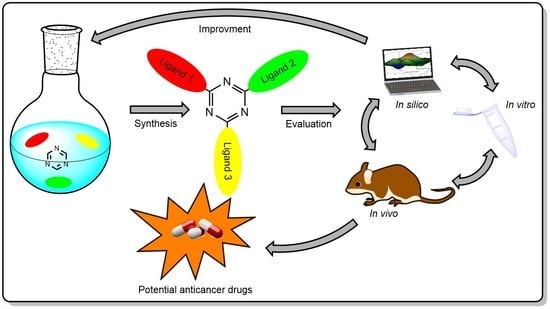

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Topoisomerase Inhibitors

2.2. Dual Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase and Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Inhibitors

2.3. Dihydrofolate Reductase Inhibitors

2.4. Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors

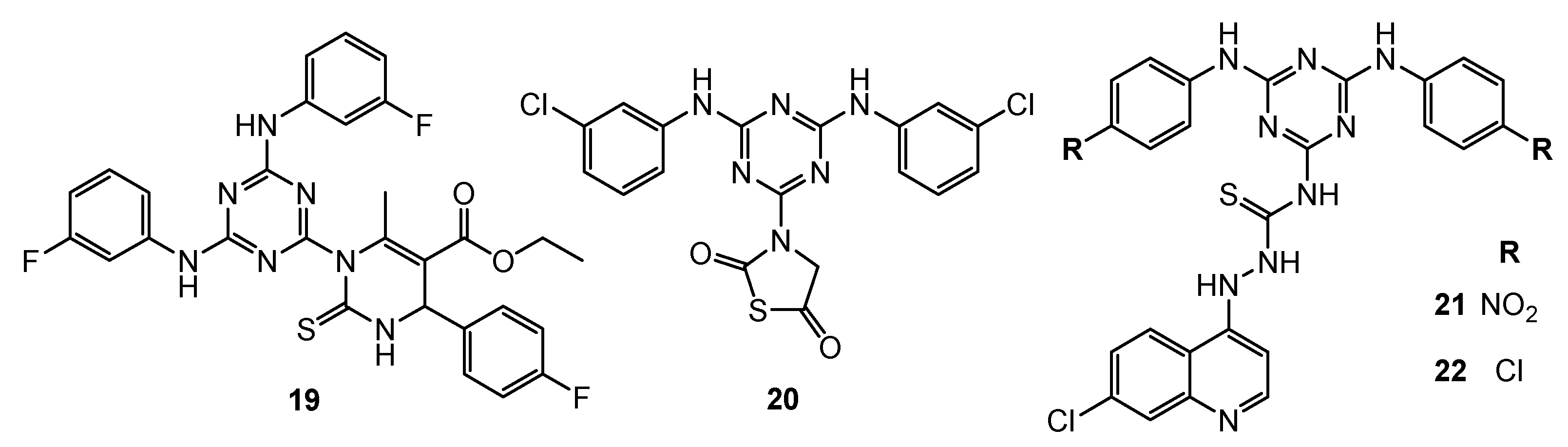

2.5. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitors

2.6. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

2.7. Focal Adhesion Kinase Inhibitors

2.8. Ubiquitin Conjugating Enzyme Inhibitors

2.9. Primary Anticancer Studies

3. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO, Regional Office for Europe. World Cancer Report: Cancer Research for Cancer Development; IARC: Lyon, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pathak, A.; Tanwar, S.; Kumar, V.; Banarjee, B.D. Present and Future Prospect of Small Molecule & Related Targeted Therapy Against Human Cancer. Vivechan Int. J. Res. 2018, 9, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

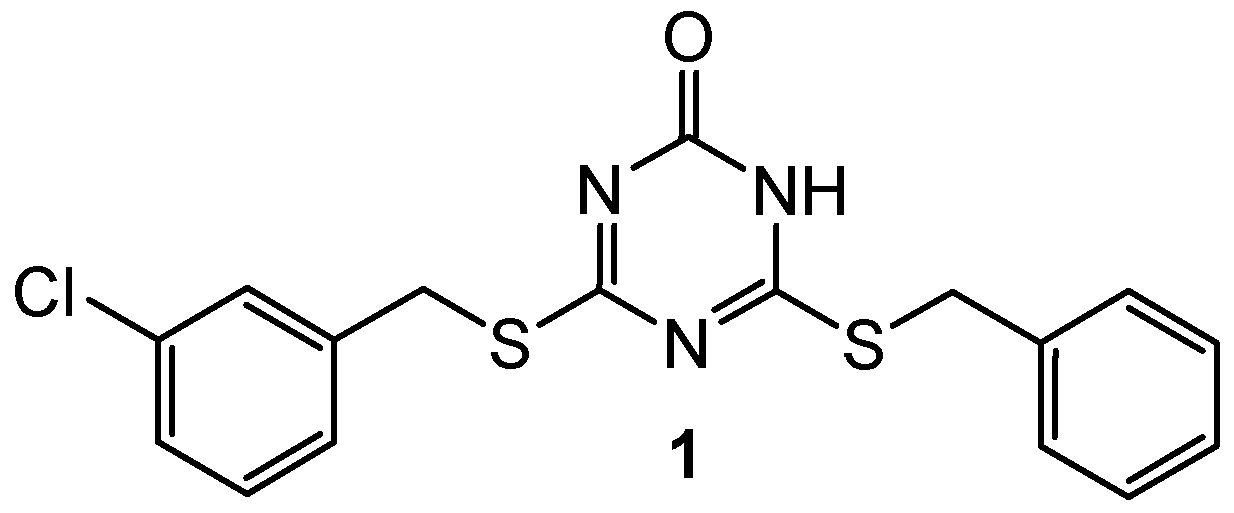

- Pogorelčnik, B.; Janežič, M.; Sosič, I.; Gobec, S.; Solmajer, T.; Perdih, A. 4,6-Substituted-1,3,5-Triazin-2(1H)-Ones as Monocyclic Catalytic Inhibitors of Human DNA Topoisomerase IIα Targeting the ATP Binding Site. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 4218–4229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

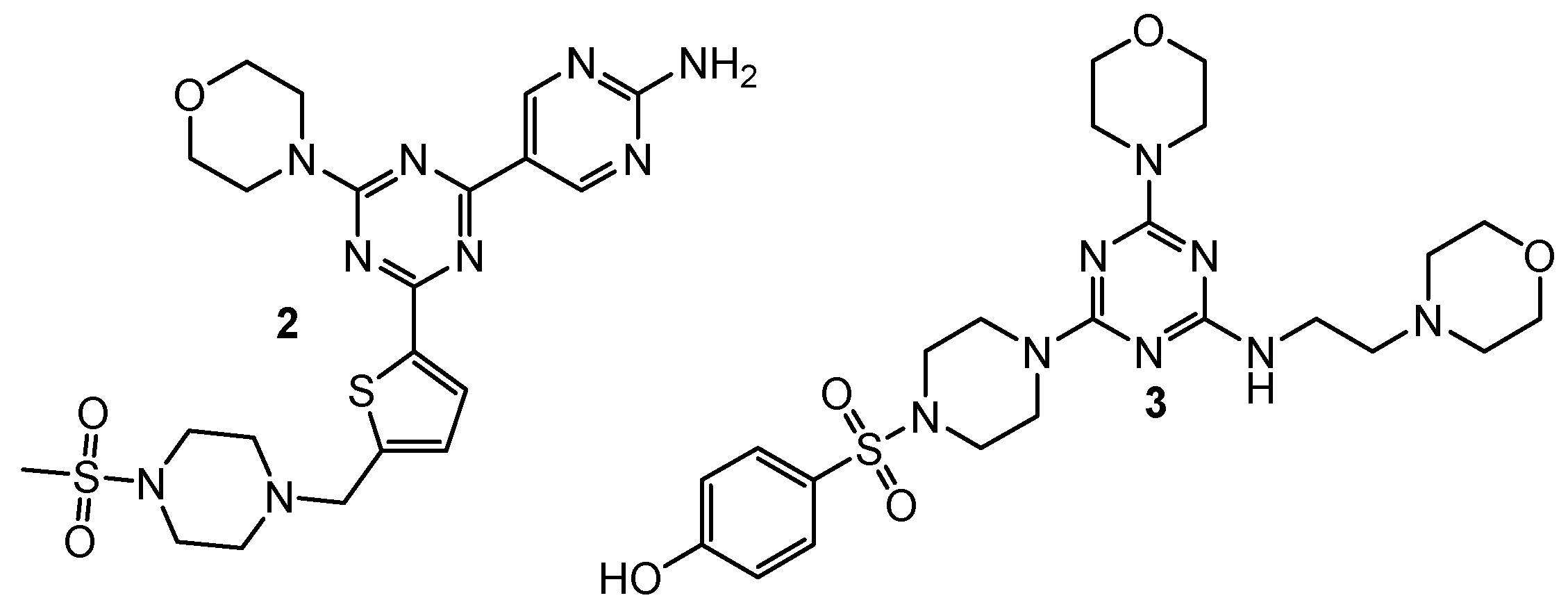

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, Q.; Xiao, Z.; Sun, X.; Yang, Z.; Gu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Xie, T.; Jin, Q.; Zheng, P.; et al. Design, Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Substituted 2-(Thiophen-2-Yl)-1,3,5-Triazine Derivatives as Potential Dual PI3Kα/MTOR Inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 95, 103525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, N.; Lu, Y.; Guo, P.; Huang, Z. Discovery of Novel 1,3,5-Triazine Derivatives as Potent Inhibitor of Cervical Cancer via Dual Inhibition of PI3K/MTOR. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 32, 115997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

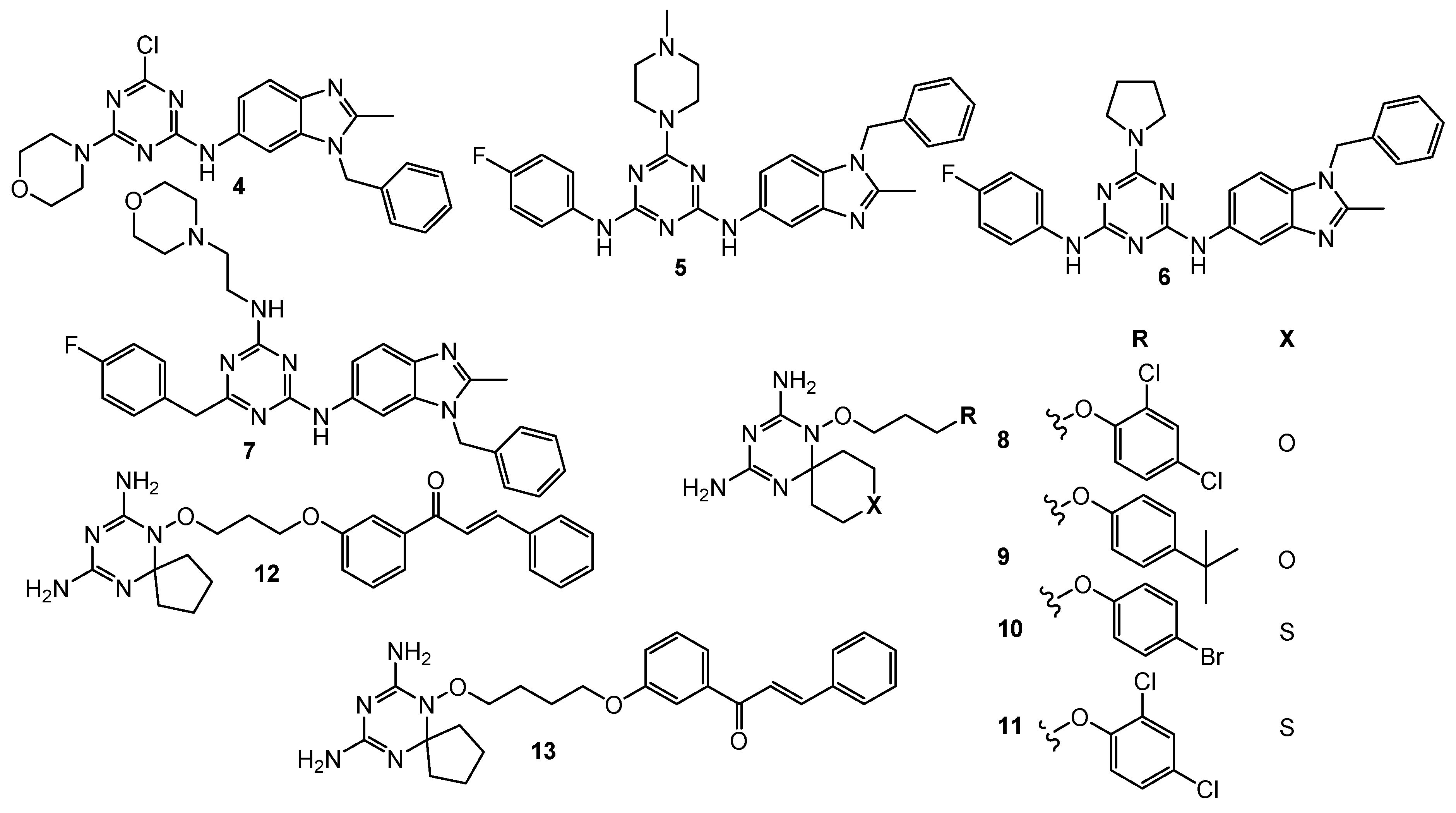

- Singla, P.; Luxami, V.; Paul, K. Synthesis, in Vitro Antitumor Activity, Dihydrofolate Reductase Inhibition, DNA Intercalation and Structure–Activity Relationship Studies of 1,3,5-Triazine Analogues. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Lin, K.; Ma, X.; Chui, W.-K.; Zhou, W. Design, Synthesis, Docking Studies and Biological Evaluation of Novel Dihydro-1,3,5-Triazines as Human DHFR Inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 125, 1279–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, H.-L.; Ma, X.; Chew, E.-H.; Chui, W.-K. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Coupled Bioactive Scaffolds as Potential Anticancer Agents for Dual Targeting of Dihydrofolate Reductase and Thioredoxin Reductase. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 1734–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żołnowska, B.; Sławiński, J.; Szafrański, K.; Angeli, A.; Supuran, C.T.; Kawiak, A.; Wieczór, M.; Zielińska, J.; Bączek, T.; Bartoszewska, S. Novel 2-(2-Arylmethylthio-4-Chloro-5-Methylbenzenesulfonyl)-1-(1,3,5-Triazin-2-Ylamino) Guanidine Derivatives: Inhibition of Human Carbonic Anhydrase Cytosolic Isozymes I and II and the Transmembrane Tumor-Associated Isozymes IX and XII, Anticancer Activity, and Molecular Modeling Studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 143, 1931–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havránková, E.; Csöllei, J.; Vullo, D.; Garaj, V.; Pazdera, P.; Supuran, C.T. Novel Sulfonamide Incorporating Piperazine, Aminoalcohol and 1,3,5-Triazine Structural Motifs with Carbonic Anhydrase I, II and IX Inhibitory Action. Bioorg. Chem. 2018, 77, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lolak, N.; Akocak, S.; Bua, S.; Supuran, C.T. Design, Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Novel Ureido Benzenesulfonamides Incorporating 1,3,5-Triazine Moieties as Potent Carbonic Anhydrase IX Inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 82, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lolak, N.; Akocak, S.; Bua, S.; Sanku, R.K.K.; Supuran, C.T. Discovery of New Ureido Benzenesulfonamides Incorporating 1,3,5-Triazine Moieties as Carbonic Anhydrase I, II, IX and XII Inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2019, 27, 1588–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, J.K.; Pillai, G.G.; Bhat, H.R.; Verma, A.; Singh, U.P. Design and Discovery of Novel Monastrol-1,3,5-Triazines as Potent Anti-Breast Cancer Agent via Attenuating Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Tyrosine Kinase. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, W.; Zhao, Y.; He, J. Anti-breast Cancer Activity of Selected 1,3,5-triazines via Modulation of EGFR-TK. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 18, 4175–4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhat, H.R.; Masih, A.; Shakya, A.; Ghosh, S.K.; Singh, U.P. Design, Synthesis, Anticancer, Antibacterial, and Antifungal Evaluation of 4-aminoquinoline-1,3,5-triazine Derivatives. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2020, 57, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, P.; Smith, N.; Tomkiewicz-Raulet, C.; Yen-Pon, E.; Camacho-Artacho, M.; Lietha, D.; Herbeuval, J.-P.; Coumoul, X.; Garbay, C.; Chen, H. Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of Novel Imidazo[1,2-a][1,3,5] Triazines and Their Derivatives as Focal Adhesion Kinase Inhibitors with Antitumor Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kothayer, H.; Spencer, S.M.; Tripathi, K.; Westwell, A.D.; Palle, K. Synthesis and in Vitro Anticancer Evaluation of Some 4,6-Diamino-1,3,5-Triazine-2-Carbohydrazides as Rad6 Ubiquitin Conjugating Enzyme Inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 2030–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- El Malah, T.; Nour, H.F.; Nayl, A.A.; Elkhashab, R.A.; Abdel-Megeid, F.M.E.; Ali, M.M. Anticancer Evaluation of Tris (Triazolyl)Triazine Derivatives Generated via Click Chemistry. Aust. J. Chem. 2016, 69, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.J.; Kumar, S.N.; Thummuri, D.; Adari, L.B.S.; Naidu, V.G.M.; Srinivas, K.; Rao, V.J. Synthesis and Characterization of New S-Triazine Bearing Benzimidazole and Benzothiazole Derivatives as Anticancer Agents. Med. Chem. Res. 2015, 24, 3991–4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Sharma, A.; Almarhoon, Z.; Al-Dhfyan, A.; El-Faham, A.; Taha, N.A.; Wadaan, M.A.M.; de la Torre, B.G.; Albericio, F. Design and Synthesis of Mono-and Di-Pyrazolyl-s-Triazine Derivatives, Their Anticancer Profile in Human Cancer Cell Lines, and in Vivo Toxicity in Zebrafish Embryos. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 87, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malebari, A.M.; Abd Alhameed, R.; Almarhoon, Z.; Farooq, M.; Wadaan, M.A.M.; Sharma, A.; de la Torre, B.G.; Albericio, F.; El-Faham, A. The Antiproliferative and Apoptotic Effect of a Novel Synthesized S-Triazine Dipeptide Series, and Toxicity Screening in Zebrafish Embryos. Molecules 2021, 26, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla, P.; Luxami, V.; Paul, K. Synthesis and in Vitro Evaluation of Novel Triazine Analogues as Anticancer Agents and Their Interaction Studies with Bovine Serum Albumin. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 117, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolnikov, S.; Gorgopina, E.; Lezhnyova, V.; Ong, G.; Chui, W.-K.; Dolzhenko, A. 4-Phenethylthio-2-Phenylpyrazolo[1,5-a][1,3,5]Triazin-7(6H)-One. Molbank 2017, 2017, M970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Makowska, A.; Sączewski, F.; Bednarski, P.; Sączewski, J.; Balewski, Ł. Hybrid Molecules Composed of 2,4-Diamino-1,3,5-Triazines and 2-Imino-Coumarins and Coumarins. Synthesis and Cytotoxic Properties. Molecules 2018, 23, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moreno, L.; Quiroga, J.; Abonia, R.; Ramírez-Prada, J.; Insuasty, B. Synthesis of New 1,3,5-Triazine-Based 2-Pyrazolines as Potential Anticancer Agents. Molecules 2018, 23, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.; Yi, Y.; Lv, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wu, K.; Wu, W.; Zhang, W. Novel 1,3,5-Triazine Derivatives Exert Potent Anti-Cervical Cancer Effects by Modulating Bax, Bcl2 and Caspases Expression. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2018, 91, 728–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharie, B.; Abbott, S.D.; Duceppe, J.; Gagnon, L.; Grouix, B.; Geerts, L.; Gervais, L.; Sarra-Bournet, F.; Perron, V.; Wilb, N.; et al. Design and Synthesis of New 1,3,5-Trisubstituted Triazines for the Treatment of Cancer and Inflammation. ChemistryOpen 2018, 7, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junaid, A.; Lim, F.P.L.; Tiekink, E.R.T.; Dolzhenko, A.V. New One-Pot Synthesis of 1,3,5-Triazines: Three-Component Condensation, Dimroth Rearrangement, and Dehydrogenative Aromatization. ACS Comb. Sci. 2019, 21, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junaid, A.; Lim, F.P.L.; Chuah, L.H.; Dolzhenko, A.V. 6, N 2 -Diaryl-1,3,5-Triazine-2,4-Diamines: Synthesis, Antiproliferative Activity and 3D-QSAR Modeling. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 12135–12144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaid, A.; Lim, F.P.L.; Tiekink, E.R.T.; Dolzhenko, A.V. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of New 6, N 2 -Diaryl-1,3,5-Triazine-2,4-Diamines as Anticancer Agents Selectively Targeting Triple Negative Breast Cancer Cells. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 25517–25528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, P.; Naumovich, V.; Grishina, M.; Shukla, P.K.; Verma, A.; Potemkin, V. Quinazoline Based 1,3,5-triazine Derivatives as Cancer Inhibitors by Impeding the Phosphorylated RET Tyrosine Kinase Pathway: Design, Synthesis, Docking, and QSAR Study. Arch. Pharm. 2019, 352, 1900053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krętowski, R.; Drozdowska, D.; Kolesińska, B.; Kamiński, Z.; Frączyk, J.; Cechowska-Pasko, M. The Cellular Effects of Novel Triazine Nitrogen Mustards in Glioblastoma LBC3, LN-18 and LN-229 Cell Lines. Investig. New Drugs 2019, 37, 984–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wróbel, A.; Kolesińska, B.; Frączyk, J.; Kamiński, Z.J.; Tankiewicz-Kwedlo, A.; Hermanowicz, J.; Czarnomysy, R.; Maliszewski, D.; Drozdowska, D. Synthesis and Cellular Effects of Novel 1,3,5-Triazine Derivatives in DLD and Ht-29 Human Colon Cancer Cell Lines. Investng. New Drugs 2020, 38, 990–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oudah, K.H.; Najm, M.A.A.; Samir, N.; Serya, R.A.T.; Abouzid, K.A.M. Design, Synthesis and Molecular Docking of Novel Pyrazolo[1,5-a][1,3,5]Triazine Derivatives as CDK2 Inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 92, 103239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorot, R.; Westphal, R.; Lemos, B.; Romagna, R.; Gonçalves, P.; Fernandes, M.; Ferreira, C.; Taranto, A.; Greco, S. Synthesis, Molecular Modelling and Anticancer Activities of New Molecular Hybrids Containing 1,4-Naphthoquinone, 7-Chloroquinoline, 1,3,5-Triazine and Morpholine Cores as PI3K and AMPK Inhibitors in the Metastatic Melanoma Cells. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2019, 30, 1860–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velihina, Y.S.; Pil’o, S.G.; Zyabrev, V.S.; Moskvina, V.S.; Shablykina, O.V.; Brovarets, V.S. 2-(Dichloromethyl)Pyrazolo[1,5-a][1,3,5]Triazines: Synthesis and Anticancer Activity. Biopolym. Cell 2020, 36, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Chang, Q.; Liang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Meng, Y.; Yi, Q. Preparation and Antitumor Effects of 4-Amino-1,2,4-Triazole Schiff Base Derivative. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 030006052090387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moreno, L.M.; Quiroga, J.; Abonia, R.; Lauria, A.; Martorana, A.; Insuasty, H.; Insuasty, B. Synthesis, Biological Evaluation, and in Silico Studies of Novel Chalcone- and Pyrazoline-Based 1,3,5-Triazines as Potential Anticancer Agents. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 34114–34129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champoux, J.J. DNA Topoisomerases: Structure, Function, and Mechanism. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001, 70, 369–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maheshwari, S.; Miller, M.S.; O’Meally, R.; Cole, R.N.; Amzel, L.M.; Gabelli, S.B. Kinetic and Structural Analyses Reveal Residues in Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase α That Are Critical for Catalysis and Substrate Recognition. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 13541–13550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hua, H.; Kong, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Luo, T.; Jiang, Y. Targeting MTOR for Cancer Therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarantelli, C.; Lupia, A.; Stathis, A.; Bertoni, F. Is There a Role for Dual PI3K/MTOR Inhibitors for Patients Affected with Lymphoma? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Osborne, M.J.; Schnell, J.; Benkovic, S.J.; Dyson, H.J.; Wright, P.E. Backbone Dynamics in Dihydrofolate Reductase Complexes: Role of Loop Flexibility in the Catalytic Mechanism. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 9846–9859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wróbel, A.; Drozdowska, D. Recent Design and Structure-Activity Relationship Studies on the Modifications of DHFR Inhibitors as Anticancer Agents. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021, 28, 910–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla, P.; Luxami, V.; Paul, K. Triazine–Benzimidazole Hybrids: Anticancer Activity, DNA Interaction and Dihydrofolate Reductase Inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 1691–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supuran, C.T.; Scozzafava, A.; Casini, A. Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors. Med. Res. Rev. 2003, 23, 146–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, F.; Abramowitz, L.; Benabderrahmane, D.; Duval, X.; Descatoire, V.; Hénin, D.; Lehy, T.; Aparicio, T. Growth Factor Receptor Expression in Anal Squamous Lesions: Modifications Associated with Oncogenic Human Papillomavirus and Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Hum. Pathol. 2009, 40, 1517–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Abbas, A.K.; Aster, J.C.; Robbins, S.L. Robbins Basic Pathology, 9th ed.; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, B.F.; Clegg, D.J. Oxygen Sensing and Metabolic Homeostasis. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2014, 397, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkkainen, M.J.; Petrova, T.V. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptors in the Regulation of Angiogenesis and Lymphangiogenesis. Oncogene 2000, 19, 5598–5605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Muller, Y.A.; Li, B.; Christinger, H.W.; Wells, J.A.; Cunningham, B.C.; de Vos, A.M. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor: Crystal Structure and Functional Mapping of the Kinase Domain Receptor Binding Site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 7192–7197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pathak, P.; Shukla, P.K.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, A.; Verma, A. Quinazoline Clubbed 1,3,5-Triazine Derivatives as VEGFR2 Kinase Inhibitors: Design, Synthesis, Docking, in Vitro Cytotoxicity and in Ovo Antiangiogenic Activity. Inflammopharmacology 2018, 26, 1441–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehlen, P.; Puisieux, A. Metastasis: A Question of Life or Death. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Cancer Cells/Effects | Targets/Effects | Reference Substance | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N/A | DNA topoisomerase IIα (IC50 = 57.6 µM) | Etoposide: DNA topoisomerase IIα (IC50 = 59.2 µM) | [3] |

| 2 | A549 (IC50 = 0.20 µM) MCF-7 (IC50 = 1.25 µM) Hela (IC50 = 1.03 µM) | PI3Kα (IC50 = 7.0 nM) mTOR (IC50 = 48 nM) | GDC-0941: A549 (IC50 = 1.21 µM), MCF-7 (IC50 = 1.47 µM), Hela (IC50 = 3.72 µM), PI3Kα (IC50 = 6.0 nM), mTOR (IC50 = 525 nM); PI-103: PI3Kα (IC50 = 5.1 nM), mTOR (IC50 = 21 nM) | [4] |

| 3 | MDA-MB321 (IC50 = 15.83 µM) MCF-7 (IC50 = 16.32 µM) Hela (IC50 = 2.21 µM) HepG2 (IC50 = 12.21 µM) | mTOR (IC50 = 8.45 nM) PI3Kα (IC50 = 3.41 nM) | Gedatolisib: mTOR (IC50 = 2.5 nM) PI3Kα (IC50 = 6.04 nM) | [5] |

| 7 | leukemia (GI50 = 1.96 µM) colon cancer (GI50 = 2.60 µM) CNS (GI50 = 2.72 µM) melanoma (GI50 = 1.91 µM) ovarian (GI50 = 4.01 µM) renal (GI50 = 3.03 µM) prostate (GI50 = 4.40 µM) breast (GI50 = 2.04 µM) | hDHFR (IC50 = 0.002 µM) | Triazine–Benzimidazole: leukemia (GI50 = 3.71 µM) colon cancer (GI50 = 2.76 µM) CNS (GI50 = 1.86 µM) melanoma (GI50 = 2.70 µM) ovarian (GI50 = 2.41 µM) renal (GI50 = 1.89 µM) prostate (GI50 = 2.75 µM) breast (GI50 = 2.58 µM) MTX: hDHFR (IC50 = 0.02 µM) | [6] |

| 8 | HCT116 (IC50 = 0.88 µM) A549 (IC50 = 0.07 µM) HL-60 (IC50 = 0.33 µM) | hDHFR (IC50 = 0.00746 µM) | MTX: HCT116 (IC50 = 0.75 µM) A549 (IC50 = 0.25 µM) HL-60 (IC50 = 1.09 µM) HepG2 (IC50 = 0.41 µM) MDA-MB-234 (IC50 = 9.49 µM) hDHFR (IC50 = 0.00667 µM) | [7] |

| 9 | HCT116 (IC50 = 1.61 µM) A549 (IC50 = 0.5 µM) HL-60 (IC50 = 0.87 µM) | hDHFR (IC50 = 0.00372 µM) | ||

| 10 | HCT116 (IC50 = 0.02 µM) A549 (IC50 = 0.74 µM) HL-60 (IC50 = 0.35 µM) HepG2 (IC50 = 1.4 µM) MDA-MB-234 (IC50 = 0.44 µM) | hDHFR (IC50 = 0.00646 µM) | ||

| 11 | HCT116 (IC50 = 0.001 µM) A549 (IC50 = 0.21 µM) HL-60 (IC50 = 0.33 µM) HepG2 (IC50 = 1.38 µM) MDA-MB-234 (IC50 = 0.06 µM) | hDHFR (IC50 = 0.00408 µM) | ||

| 12 | HCT116 (GI50 = 0.026 µM) MCF-7 (GI50 = 0.08 µM) | hDHFR (IC50 = 0.0061 µM) rat TrxR (IC50 = 4.6 µM) | MTX: hDHFR (IC50 = 0.0079 µM) HCT116 (GI50 = 0.015 µM) MCF-8 (GI50 = 0.024 µM) | [8] |

| 13 | HCT116 (GI50 = 0.116 µM) MCF-8 (GI50 = 0.127 µM) | hDHFR (IC50 = 0.0026 µM) rat TrxR (IC50 = 5.9 µM) | ||

| 14 | HeLa (IC50 = 16 µM) HaCaT (IC50 = 61 µM) | hCAI (KI = 733.3 nM) hCAII (KI = 160.8 nM) hCAIX (KI = 41.1 nM) hCAXII (KI = 77.6 nM) | AAZ: hCAI (KI = 250 nM) hCAII (KI = 12.1 nM) hCAIX (KI = 25.8 nM) hCAXII (KI = 5.7 nM) MZA: hCAI (KI = 780 nM) hCAII (KI = 14 nM) hCAIX (KI = 27 nM) hCAXII (KI = 3.4 nM) EZA: hCAI (KI = 25 nM) hCAII (KI = 8 nM) hCAIX (KI = 34 nM) hCAXII (KI = 22 nM) DCP: hCAI (KI = 1200 nM) hCAII (KI = 38 nM) hCAIX (KI = 50 nM) hCAXII (KI = 50 nM) | [9] |

| 15 | N/A | hCAI (KI = 16.7 nM) hCAII (KI = 7.4 nM) hCAIX (KI = 0.4 nM) | [10] | |

| 16 | N/A | hCAI (KI = 2679.1 nM) hCAII (KI = 380.5 nM) hCAIX (KI = 27.0 nM) | ||

| 17 | N/A | hCAI (KI = 394.9 nM) hCAII (KI = 3.1 nM) hCAIX (KI = 0.91 nM) | [11] | |

| 18 | N/A | hCAI (KI = 441.7 nM) hCAII (KI = 152.9 nM) hCAIX (K = 14.6 nM) hCAXII (KI = 44.4 nM) | [12] | |

| 19 | HeLa (IC50 = 39.7 µM) MCF-7 (IC50 = 41.5 µM) HL-60 (IC50 = 23.1 µM) HepG2 (IC50 = 31.2 µM) | EGFR-TK (Inhibition rate = 94.3%; C = 10 µM) | Cisplatin: HeLa (IC50 = 32.5 µM) MCF-7 (IC50 = 24.4 µM) HL-60 (IC50 = 12.3 µM) HepG2 (IC50 = 25.9 µM) Erlotinib: EGFR-TK (Inhibition rate = 100%; C = 10 µM); | [13] |

| 20 | N/A | EGFR-TK (IC50 = 2.54 µM) | Dacomitinib: EGFR-TK (IC50 = 0.06 µM) | [14] |

| 21 | HeLa (IC50 = 44.5 µM) MCF-7 (IC50 = 52.2 µM) HL-60 (IC50 = 40.3 µM) HepG2 (IC50 = 56.4 µM) | EGFR-TK (Inhibition rate = 96.3%; C = 10 µM) | Cisplatin: HeLa (IC50 = 31.3 µM) MCF-7 (IC50 = 22.5 µM) HL-60 (IC50 = 14.3 µM) HepG2 (IC50 = 26.4 µM) Erlotinib: EGFR-TK (Inhibition rate = 100%; C = 10 µM) | [15] |

| 22 | HeLa (IC50 = 32.4 µM) MCF-7 (IC50 = 32.3 µM) HL-60 (IC50 = 26.3 µM) HepG2 (IC50 = 45.3 µM) | EGFR-TK (Inhibition rate = 90.5%; C = 10 µM) | ||

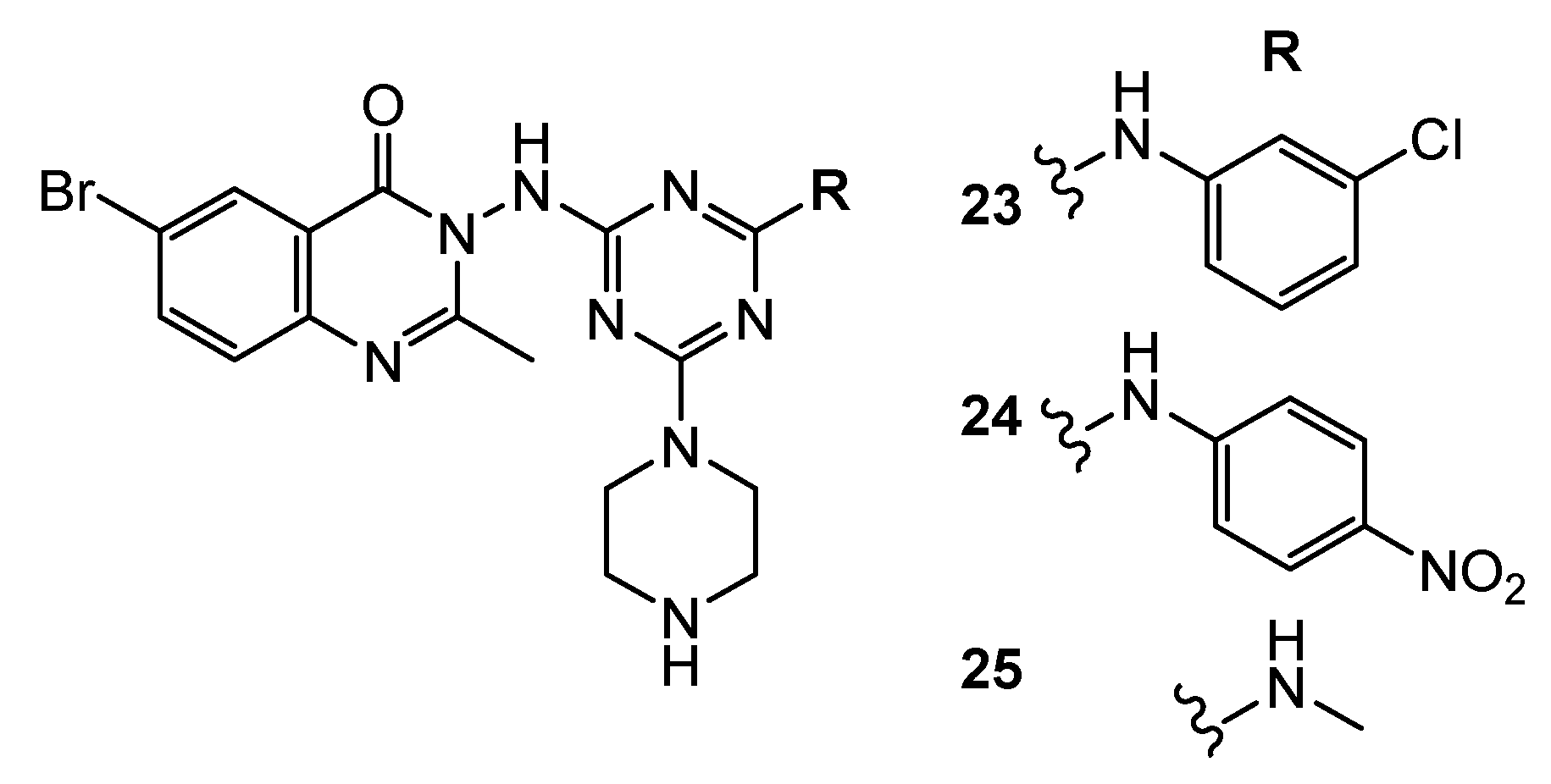

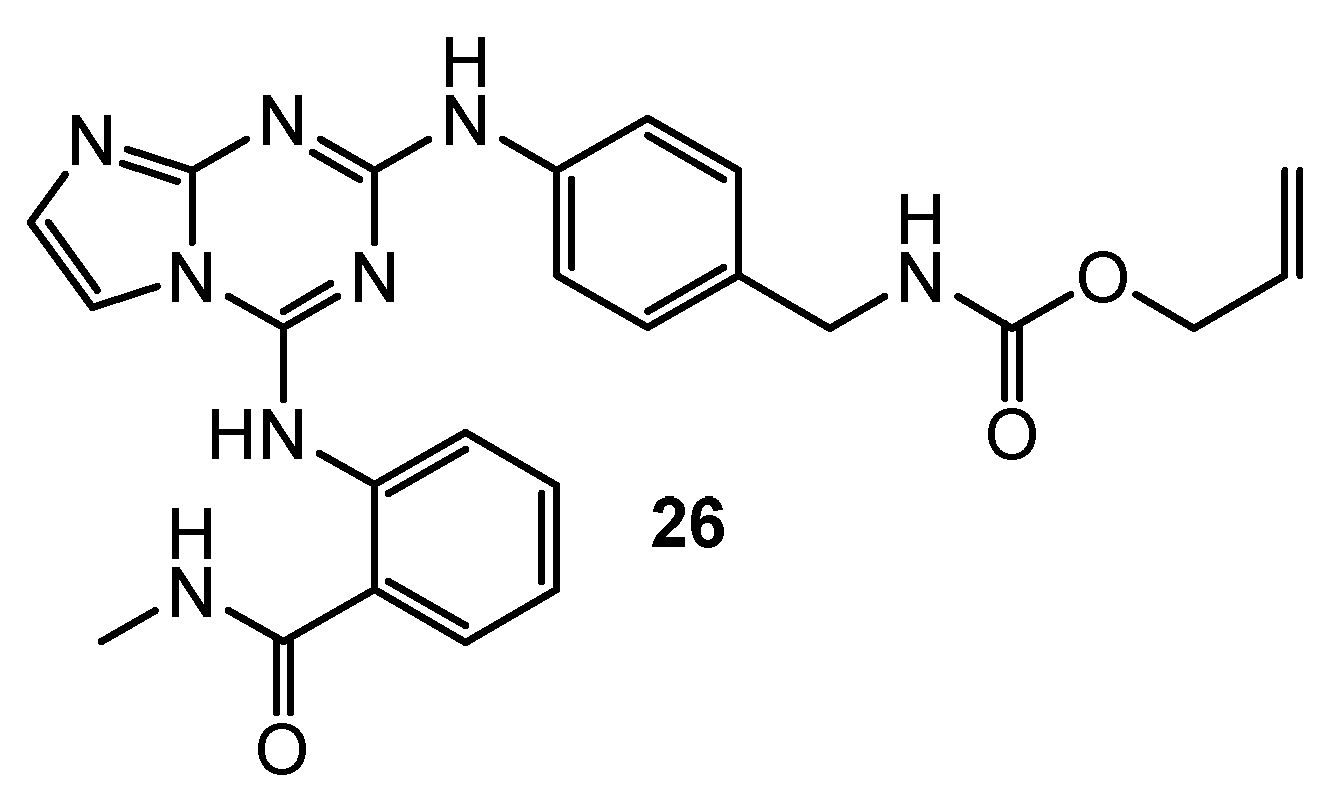

| 26 | U-87MG (IC50 = 0.42 µM) HCT-116 (IC50 = 0.13 µM) MDA-MB-231 (IC50 = 0.14 µM) PC-3 (IC50 = 0.63 µM) | FAK (IC50 = 50 nM) | TAE-226: U-87MG (IC50 = 0.19 µM) HCT-116 (IC50 = 0.23 µM) MDA-MB-231 (IC50 = 1.9 µM) PC-3 (IC50 = 0.26 µM) FAK (IC50 = 7 nM) | [16] |

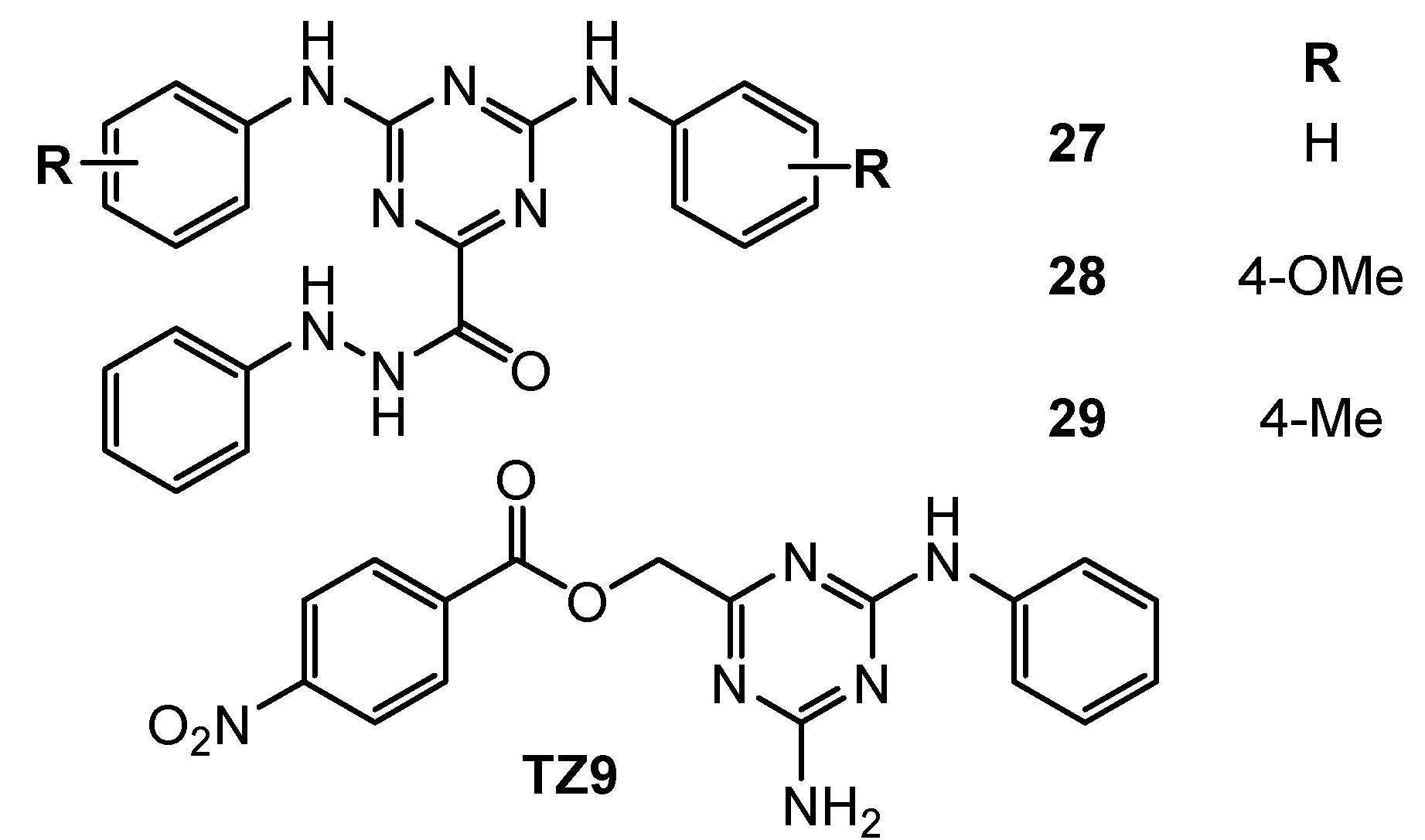

| 27 | HT-29 (IC50 = 9.5 µM) H1299 (IC50 = 11 µM) A549 (IC50 = 14.6 µM) MDA-MB-231 (IC50 = 2.5 µM) OV90 (IC50 = 8 µM) A2780 (IC50 = 7.1 µM) MCF-7 (IC50 = 6 µM) | Rad6 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme (nd) | TZ9: HT-29 (IC50 = 8.3 µM) H1299 (IC50 = 45 µM) A549 (IC50 = 7.2 µM) MDA-MB-231 (IC50 = 4.6 µM) OV90 (IC50 = 60 µM) A2780 (IC50 = 7.8 µM) MCF-7 (IC50 = 5 µM) | [17] |

| 28 | HT-29 (IC50 = 5.8 µM) H1299 (IC50 = 5 µM) A549 (IC50 = 10.8 µM) MDA-MB-231 (IC50 = 4.2 µM) OV90 (IC50 = 12 µM) A2750 (IC50 = 6.3 µM) MCF-7 (IC50 = 7.2 µM) | |||

| 29 | HT-29 (IC50 = 5.2 µM) H1299 (IC50 = 22 µM) A549 (IC50 = 11.6 µM) MDA-MB-231 (IC50 = 3.5 µM) OV90 (IC50 = 5 µM) A2750 (IC50 = 3.6 µM) MCF-7 (IC50 = 4.2 µM) | |||

| 30 | MCF-7 (IC50 = 2.95 µg/mL) HepG2 (IC50 = 3.7 µg/mL) | N/A | Doxorubicin: MCF-7 (IC50 = 2.98 µg/mL) HepG2 (IC50 = 3.82 µg/mL) | [18] |

| 31 | MCF-7 (IC50 = 4.8 µM) MDA-MB-231 (IC50 = 48.3 µM) HT-29 (IC50 = 9.8 µM) HGC-27 (IC50 = 15.1 µM) | N/A | ZSTK474: MDA-MB-231 (IC50 = 10.8 µM) HT-29 (IC50 = 25.1 µM) HGC-27 (IC50 = 1.11 µM) | [19] |

| 32 | MCF7 (IC50 = 5 µM) MDA-MB-231 (IC50 = 15 µM) HepG2 (IC50 = 21.1 µM) LoVo (IC50 = 8.4 µM) K-562 (IC50 = 5.9 µM) | Arrest cell proliferation in S and G2/M phase. None lethal for zebrafish embryos. | N/A | [20] |

| 33 | MCF7 (IC50 = 7.5 µM) MDA-MB-231 (IC50 = 14 µM) HepG2 (IC50 = 17.5 µM) LoVo (IC50 = 6.1 µM) K-562 (IC50 = 9.8 µM) | |||

| 34 | MCF-7 (IC50 = 0.82 µM) MDA-MB-231 (IC50 = 9.36 µM) HCT-116 (IC50 = 17.89 µM) | Arrest of MCF-7 cells in the G2/M stage(36.8%). Mortality response of zebrafish embryos—na. | Tamoxifen: MCF-7 (IC50 = 5.12 µM) MDA-MB-231 (IC50 = 15.01 µM) HCT-116 (IC50 = 26.41 µM) | [21] |

| 35 | MG-MID (GI50 = 2.68 µM; TGI = 11 µM; LC50 = 32.3 µM) | BSA (distance in complex = 7.9 nm) | N/A | [22] |

| 36 | MG-MID (GI50 = 1.38 µM; TGI = 3.15 µM; LC50 = 8.63 µM) | BSA (distance in complex = 6.61 nm) | ||

| 37 | MG-MID (GI50 = 2.37 µM; TGI = 7.16 µM; LC50 = 7.88 µM) | BSA (distance in complex = 7.62 nm) | ||

| 38 | MG-MID (GI50 = 0.72 µM; TGI = 1.8 µM; LC50 = 4.88 µM) | BSA (distance in complex = 7.98 nm) | ||

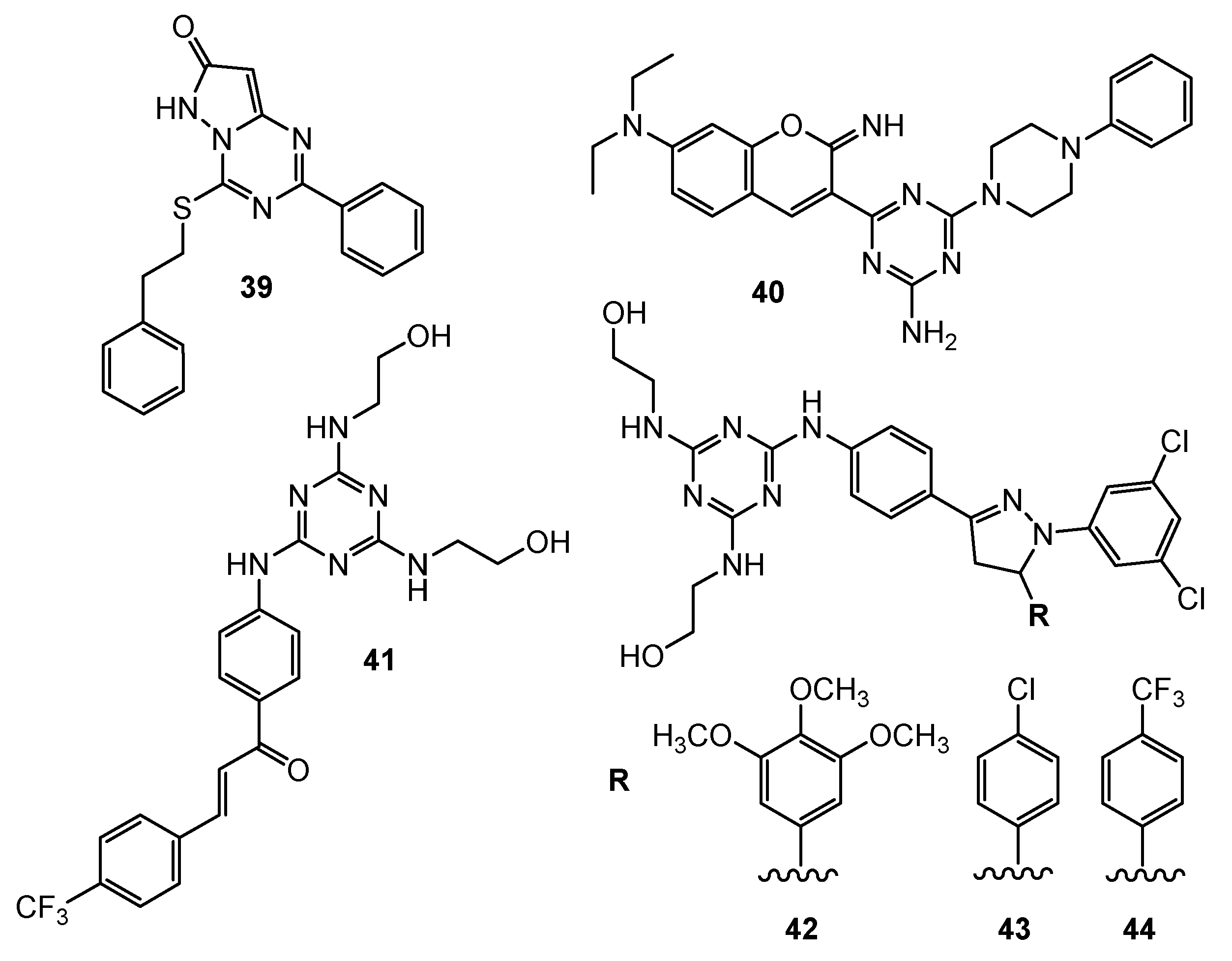

| 39 | A549 (IC50 = 53 µM) | N/A | Floxuridine: A549 (IC50 = 5.8 µM) | [23] |

| 40 | DAN-G (IC50 = 2.14 µM) A-427 (IC50 = 1.51 µM) LCLC-103H (IC50 = 2.21 µM) SISO (IC50 = 2.6 µM) RT-4 (IC50 = 1.66 µM) | Ct-DNA (potencial target) | Cisplatin: DAN-G (IC50 = 0.73 µM)A-427 (IC50 = 1.96 µM) LCLC-103H (IC50 = 0.90 µM) SISO (IC50 = 0.24 µM) RT-4 (IC50 = 1.61 µM) | [24] |

| 41 | UO-31 (GI50 = 1.54 µM) | N/A | N/A | [25] |

| 42 | RXF 393 (GI50 = 0.569 µM) HS 578 (GI50 = 0.644 µM) | |||

| 43 | SF-539 (GI50 = 1.35 µM) | |||

| 44 | SF-539 (GI50 = 1.18 µM) | |||

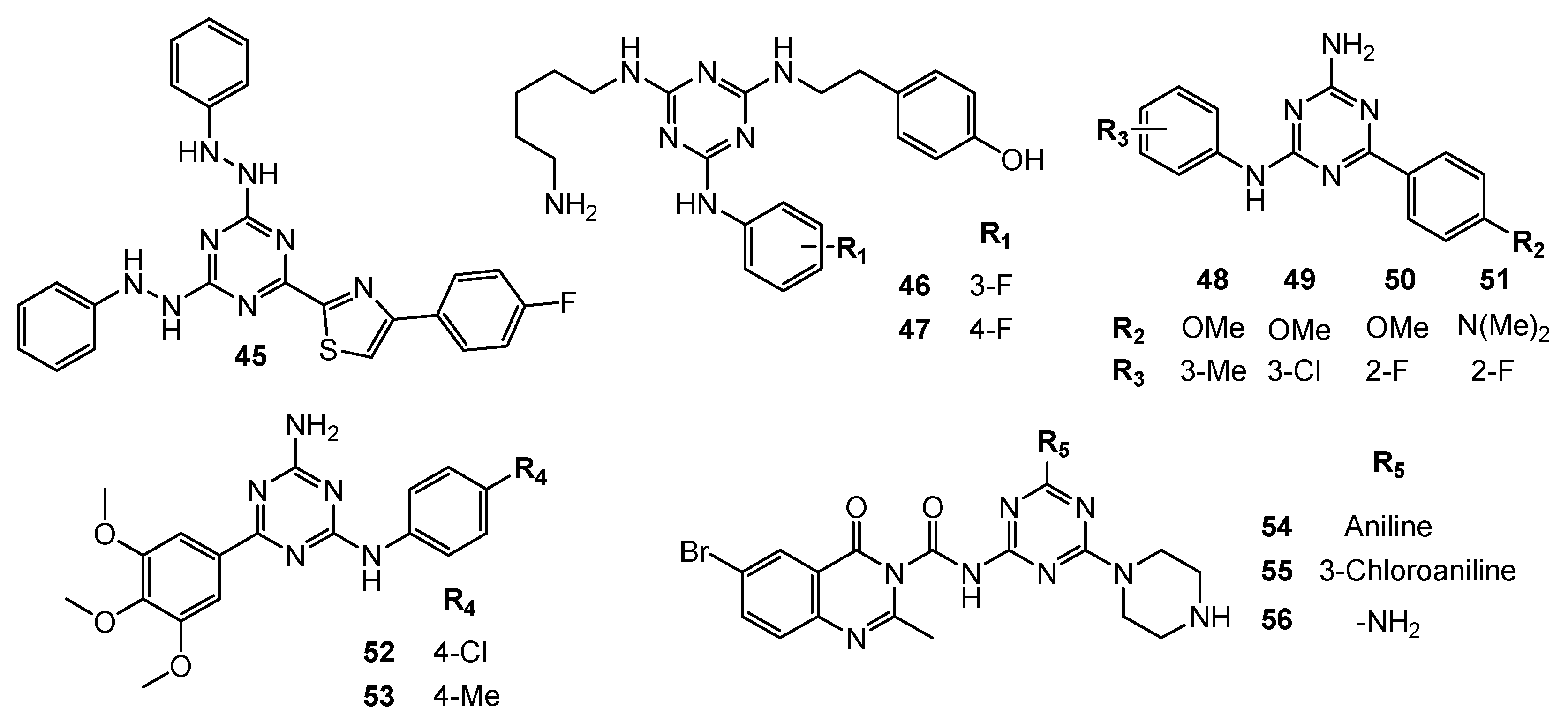

| 45 | MDA-MB-231 (IC50 = 4.3 µg/mL) HeLa (IC50 = 2.21 µg/mL) KG1a (IC50 = 6.45 µg/mL) Jurkat (IC50 = 28.33 µg/mL) SiHa (IC50 = 1.34 µg/mL) CaSki (IC50 = 4.56 µg/mL) DoTc2 (IC50 = 2.15 µg/mL) | Increase concentration of C-caspase-3, C-caspase-9 and Bcl-2. Decrease of Bax. Tumor reduction in nude mouse (C = 10 µM). | Erlotinib: MDA-MB-231 (IC50 = 0.16 µg/mL) HeLa (IC50 = 0.21 µg/mL) KG1a (IC50 = 0.18 µg/mL) Jurkat (IC50 = 22.43 µg/mL) SiHa (IC50 = 0.25 µg/mL) CaSki (IC50 = 0.34 µg/mL) DoTc2 (IC50 = 0.28 µg/mL) | [26] |

| 46 | N/A | TNF-α (IC50 = 29 µM) | N/A | [27] |

| 47 | PC-3 (IC50 = 43.3 µM) | TNF-α (IC50 = 13 µM), inducing cell-cycle arrest at the G0/G1 phase (J774 cell line). | ||

| 48 | DU145 (GI50 = 3.43 µM) | N/A | Nilotinib: DU145 (GI50 = 6.35 µM) | [28] |

| 49 | DU145 (GI50 = 4.01 µM) | |||

| 50 | DU145 (GI50 = 2.38 µM) | |||

| 51 | DU145 (GI50 = 0.67 µM) | |||

| 52 | MDA-MB231 (GI50 = 0.007 µM) SKBR-3 (GI50 = 0.3 µM) MCF-7 (GI50 = 12.5 µM) | N/A | MTX: MDA-MB231 (GI50 = 0.01 µM) MCF-7 (GI50 = 5.79 µM) Nilotinib: MDA-MB231 (GI50 = 0.04 µM) SKBR-3 (GI50 = 9.6 µM) | [29,30] |

| 53 | MDA-MB231 (GI50 = 0.001 µM) SKBR-3 (GI50 = 0.21 µM) | |||

| 54 | MCF-7 (IC50 = 14.85 µM) TPC-1 (IC50 = 9.23 µM) | Phosphorylated TK (Inhibition rate = 94.4%; C = 10 µM) | Vandatinib: MCF-7 (IC50 = 10.42 µM) TPC-1 (IC50 = 7.63 µM) Phosphorylated TK (Inhibition rate = 98.6%; C = 10 µM) | [31] |

| 55 | MCF-7 (IC50 = 12.5 µM) TPC-1 (IC50 = 7.16 µM) | Phosphorylated TK (Inhibition rate = 96.4%; C = 10 µM) | ||

| 56 | MCF-7 (IC50 = 14.43 µM) TPC-1 (IC50 = 8.8 µM) | Phosphorylated TK (Inhibition rate = 94.3%; C = 10 µM) | ||

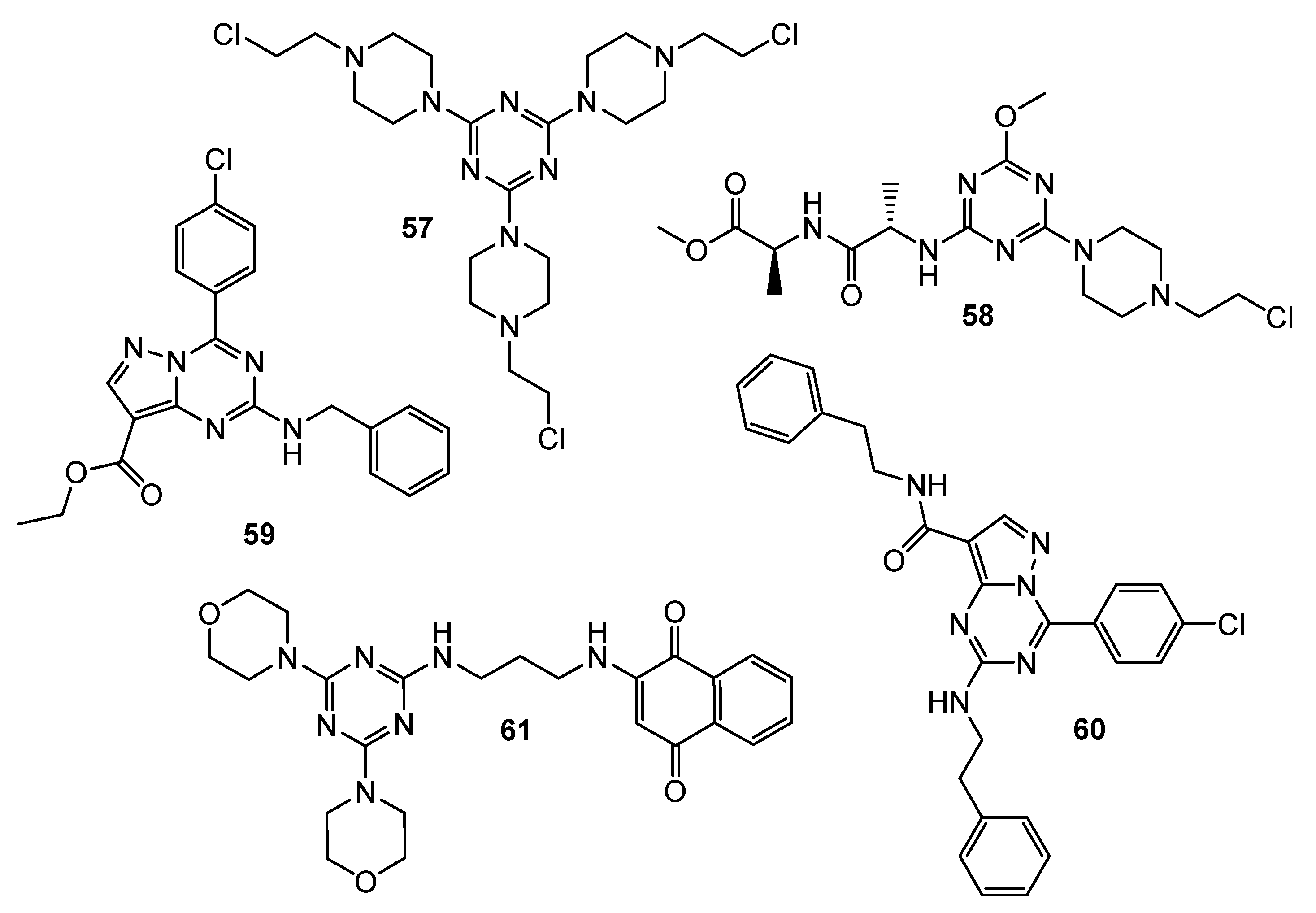

| 57 | LN-18 (IC50 = 46 µM) LN-229 (IC50 = 50 µM) LBC3 (IC50 = 40 µM) | N/A | N/A | [32] |

| 58 | DLD-1 (IC50 = 13.71 µM) HT-29 (IC50 = 17.78 µM) | BAX (increase); Bcl-2 (decrease) | 5-FU: DLD-1 (IC50 = 27.22 µM) HT-29 (IC50 = 21.72 µM) | [33] |

| 59 | HCT-116 (Inhibition = 115.53%) SW-620 (Inhibition = 95.06%) SF-539 (Inhibition = 89.27%) OVCAR-4 (Inhibition = 94.39%) PC786-0 (Inhibition = 93.76%) ACHN (Inhibition = 86.27%) MCF-7 (Inhibition = 94.82%) | CDK2 (Inhibition rate = 82.38%; C = 10 µM; IC50 = 1.85 µM) | Roscovitine: CDK2 (Inhibition rate = 89.6%; C = 10 µM) | [34] |

| 60 | ATCC (Inhibition = 90.02%) NCI-H460 (Inhibition = 83.66%) OVCAR-4 (Inhibition = 92.27%) | CDK2 (Inhibition rate = 81.96%; C = 10 µM; IC50 = 2.09 µM) | ||

| 61 | SKMEL-103 (IC50 = 25 µM) | PI3K (decrease)AMPK (decrease) | N/A | [35] |

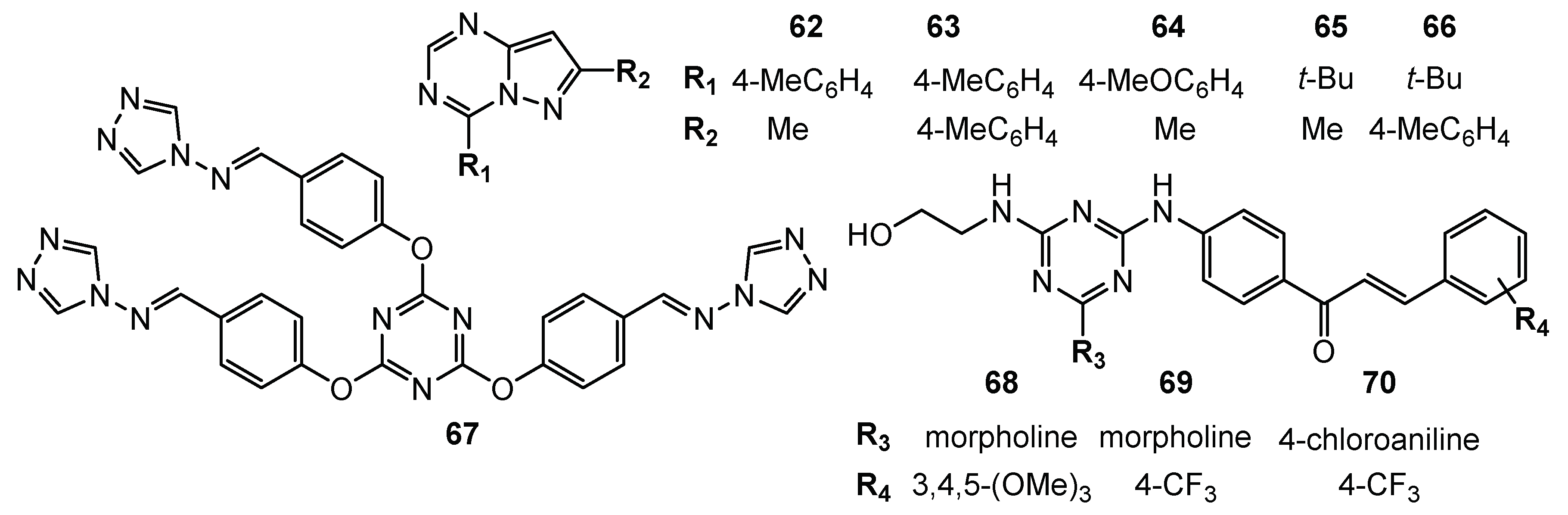

| 62 | NCI-H460 (Growth Percent = −50%) MDA-MB468 (Growth Percent = −20.7%) | N/A | N/A | [36] |

| 63 | HCC-2998 (Growth Percent = −82.1%) RXF 393 (Growth Percent = −68%) NCI-H460 (Growth Percent = −58.3%) ACHN (Growth Percent = −57%) MDA-MB-468 (Growth Percent = −52.3%) | |||

| 64 | HCC-2998 (Growth Percent = −69.3%) RXF 393 (Growth Percent = −66%) NCI-H460 (Growth Percent = −64.8%) ACHN (Growth Percent = −45%) | |||

| 65 | HCC-2998 (Growth Percent = −77%) RXF 393 (Growth Percent = −74.4%) NCI-H460 (Growth Percent = −49.4%) MDA-MB-468 (Growth Percent = −47%) | |||

| 66 | HCC-2998 (Growth Percent = −53.7%) RXF 393 (Growth Percent = −55%) NCI-H460 (Growth Percent = −54.7%) ACHN (Growth Percent = −52.8%) NCI-H322M (Growth Percent = −50.5%) | |||

| 67 | A549 (IC50 = 144.1 µg/mL) Bel7402 (IC50 = 195.6 µg/mL) | N/A | N/A | [37] |

| 68 | leukemia (Mean GI50 = 0.96 µM) colon cancer (Mean GI50 = 1.64 µM) CNS (Mean GI50 = 1.80 µM) melanoma (Mean GI50 = 1.62 µM) ovarian (Mean GI50 = 2.12 µM) renal (Mean GI50 = 1.66 µM) prostate (Mean GI50 = 1.75 µM) breast (Mean GI50 = 1.59 µM) | N/A | N/A | [38] |

| 69 | leukemia (Mean GI50 = 2.55 µM) colon cancer (Mean GI50 = 1.92 µM) CNS (Mean GI50 = 2.09 µM) melanoma (Mean GI50 = 3.4 µM) ovarian (Mean GI50 = 2.67 µM) renal (Mean GI50 = 1.80 µM) prostate (Mean GI50 = 1.2.22 µM) breast (Mean GI50 = 2.03 µM) | |||

| 70 | leukemia (Mean GI50 = = 4.14 µM) colon cancer (Mean GI50 = 1.92 µM) CNS (Mean GI50 = 3.13 µM) melanoma (Mean GI50 = 7.84 µM) ovarian (Mean GI50 = 6.05 µM) renal (Mean GI50 = 3.28 µM) prostate (Mean GI50 = 4.54 µM) breast (Mean GI50 = 3.42 µM) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maliszewski, D.; Drozdowska, D. Recent Advances in the Biological Activity of s-Triazine Core Compounds. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15020221

Maliszewski D, Drozdowska D. Recent Advances in the Biological Activity of s-Triazine Core Compounds. Pharmaceuticals. 2022; 15(2):221. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15020221

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaliszewski, Dawid, and Danuta Drozdowska. 2022. "Recent Advances in the Biological Activity of s-Triazine Core Compounds" Pharmaceuticals 15, no. 2: 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15020221

APA StyleMaliszewski, D., & Drozdowska, D. (2022). Recent Advances in the Biological Activity of s-Triazine Core Compounds. Pharmaceuticals, 15(2), 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15020221