Antioxidant Properties of Second-Generation Antipsychotics: Focus on Microglia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Schizophrenia and Oxidative Stress

2.1. The Neurobiological Link between Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Schizophrenia

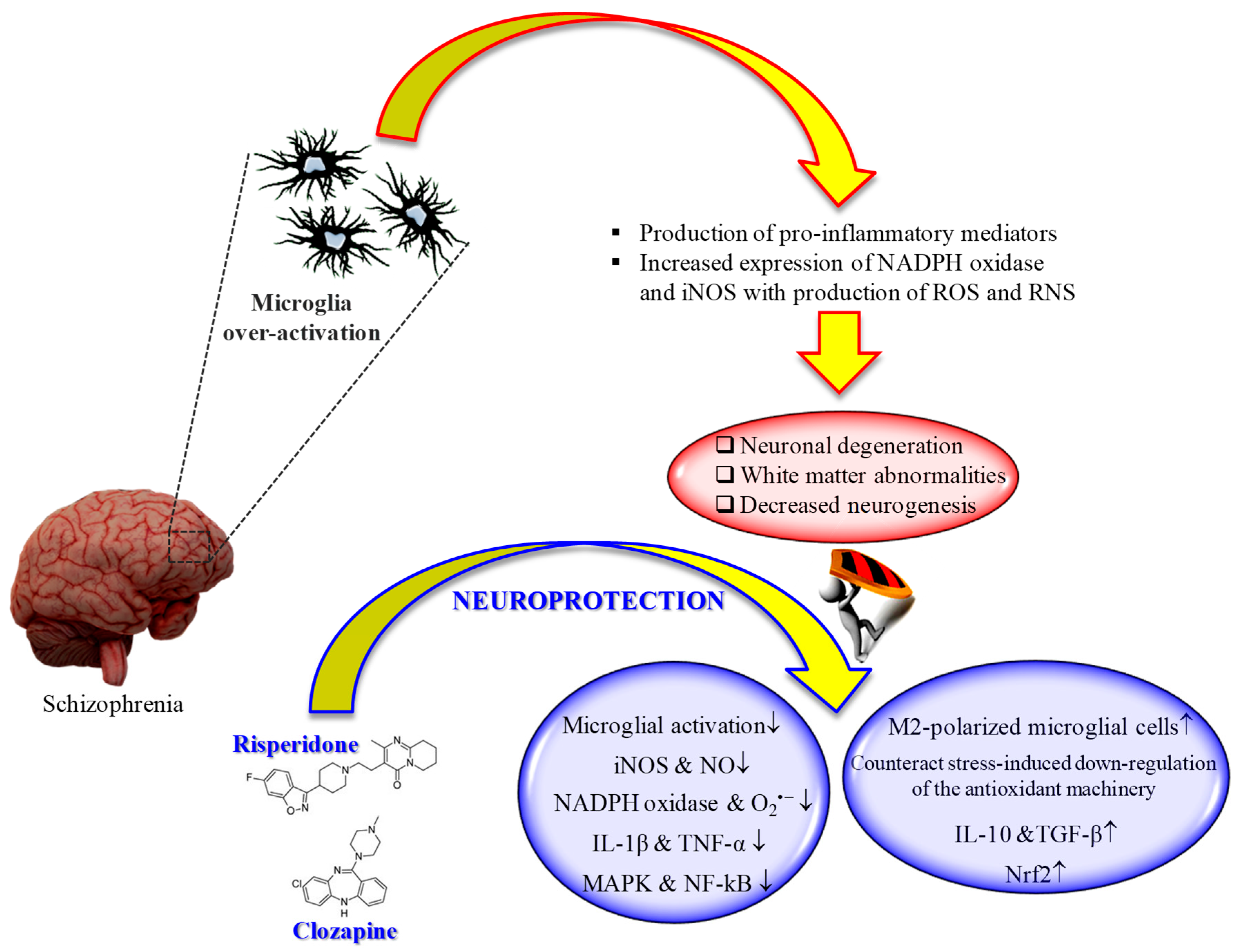

2.2. Oxidative Stress in Schizophrenic Patients: Role of the Antioxidant Machinery

3. First-Generation Antipsychotics (FGAs) and Oxidative Stress: The Strange Case of Haloperidol

4. Second-Generation Antipsychotics: Can They Exert an Antioxidant Activity?

Antioxidant Treatments in Schizophrenia

5. Effects of Second-Generation Antipsychotics on Microglia: Therapeutic Potential for the Treatment of Schizophrenia

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Landek-Salgado, M.A.; Faust, T.E.; Sawa, A. Molecular substrates of schizophrenia: Homeostatic signaling to connectivity. Mol. Psychiatry 2016, 21, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1789–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, D.R. The pathogenesis of schizophrenia: A neurodevelopmental theory. In Neurol. Schizophr; Nasrallah, H.A., Weinberger, D.R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1986; pp. 397–406. [Google Scholar]

- Möller, M.; Swanepoel, T.; Harvey, B.H. Neurodevelopmental animal models reveal the convergent role of neurotransmitter systems, inflammation, and oxidative stress as biomarkers of schizophrenia: Implications for novel drug development. Acs Chem. Neurosci. 2015, 6, 987–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, T.L.; Sachdeva, S.; Stahl, S.M. Glutamate neurocircuitry: Theoretical underpinnings in schizophrenia. Front. Pharmacol. 2012, 3, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brisch, R.; Saniotis, A.; Wolf, R.; Bielau, H.; Bernstein, H.G.; Steiner, J.; Bogerts, B.; Braun, K.; Jankowski, Z.; Kumaratilake, J.; et al. The role of dopamine in schizophrenia from a neurobiological and evolutionary perspective: Old fashioned, but still in vogue. Front. Psychiatry 2014, 5, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Schiavone, S.; Colaianna, M.; Curtis, L. Impact of early life stress on the pathogenesis of mental disorders: Relation to brain oxidative stress. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015, 21, 1404–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Fresta, C.G.; Musso, N.; Giambirtone, M.; Grasso, M.; Spampinato, S.F.; Merlo, S.; Drago, F.; Lazzarino, G.; Sortino, M.A.; et al. Carnosine prevents Aβ-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in microglial cells: A key role of TGF-β1. Cells 2019, 8, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Benatti, C.; Blom, J.M.C.; Caraci, F.; Tascedda, F. The many faces of mitochondrial dysfunction in depression: From pathology to treatment. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emiliani, F.E.; Sedlak, T.W.; Sawa, A. Oxidative stress and schizophrenia: Recent breakthroughs from an old story. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2014, 27, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, E.M.; O’Donnell, P. Inhibitory interneurons, oxidative stress, and schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2012, 38, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homayoun, H.; Moghaddam, B. Nmda receptor hypofunction produces opposite effects on prefrontal cortex interneurons and pyramidal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 11496–11500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabinovic, A.D.; Lewis, D.A.; Hastings, T.G. Role of oxidative changes in the degeneration of dopamine terminals after injection of neurotoxic levels of dopamine. Neuroscience 2000, 101, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masserano, J.M.; Baker, I.; Venable, D.; Gong, L.; Zullo, S.J.; Merril, C.R.; Wyatt, R.J. Dopamine induces cell death, lipid peroxidation and DNA base damage in a catecholaminergic cell line derived from the central nervous system. Neurotox. Res. 2000, 1, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.R.; Petronilho, F.C.; Gomes, K.M.; Dal-Pizzol, F.; Streck, E.L.; Quevedo, J. Antipsychotic-induced oxidative stress in rat brain. Neurotox. Res. 2008, 13, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillai, A.; Parikh, V.; Terry, A.V., Jr.; Mahadik, S.P. Long-term antipsychotic treatments and crossover studies in rats: Differential effects of typical and atypical agents on the expression of antioxidant enzymes and membrane lipid peroxidation in rat brain. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2007, 41, 372–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garay, R.P.; Citrome, L.; Samalin, L.; Liu, C.C.; Thomsen, M.S.; Correll, C.U.; Hameg, A.; Llorca, P.M. Therapeutic improvements expected in the near future for schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: An appraisal of phase iii clinical trials of schizophrenia-targeted therapies as found in us and eu clinical trial registries. Expert Opin. Pharm. 2016, 17, 921–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodward, N.D.; Purdon, S.E.; Meltzer, H.Y.; Zald, D.H. A meta-analysis of neuropsychological change to clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in schizophrenia. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005, 8, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caraci, F.; Enna, S.J.; Zohar, J.; Racagni, G.; Zalsman, G.; van den Brink, W.; Kasper, S.; Koob, G.F.; Pariante, C.M.; Piazza, P.V.; et al. A new nomenclature for classifying psychotropic drugs. Br. J. Clin. Pharm. 2017, 83, 1614–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmi, M.; Murru, A.; Pacchiarotti, I.; Undurraga, J.; Veronese, N.; Fornaro, M.; Stubbs, B.; Monaco, F.; Vieta, E.; Seeman, M.V.; et al. Safety, tolerability, and risks associated with first- and second-generation antipsychotics: A state-of-the-art clinical review. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2017, 13, 757–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, L.; Yang, J.; Bresee, L.; Jette, N.; Patten, S.; Pringsheim, T. Second-generation antipsychotics and metabolic side effects: A systematic review of population-based studies. Drug Saf. 2017, 40, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancampfort, D.; Stubbs, B.; Mitchell, A.J.; De Hert, M.; Wampers, M.; Ward, P.B.; Rosenbaum, S.; Correll, C.U. Risk of metabolic syndrome and its components in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 2015, 14, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vancampfort, D.; Correll, C.U.; Galling, B.; Probst, M.; De Hert, M.; Ward, P.B.; Rosenbaum, S.; Gaughran, F.; Lally, J.; Stubbs, B. Diabetes mellitus in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: A systematic review and large scale meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pringsheim, T.; Lam, D.; Ching, H.; Patten, S. Metabolic and neurological complications of second-generation antipsychotic use in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Drug Saf. 2011, 34, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianfrancesco, F.D.; Grogg, A.L.; Mahmoud, R.A.; Wang, R.H.; Nasrallah, H.A. Differential effects of risperidone, olanzapine, clozapine, and conventional antipsychotics on type 2 diabetes: Findings from a large health plan database. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2002, 63, 920–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leucht, S.; Cipriani, A.; Spineli, L.; Mavridis, D.; Orey, D.; Richter, F.; Samara, M.; Barbui, C.; Engel, R.R.; Geddes, J.R.; et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: A multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 2013, 382, 951–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakhale, G.; Khanzode, S.; Khanzode, S.; Saoji, A.; Khobragade, L.; Turankar, A. Oxidative damage and schizophrenia: The potential benefit by atypical antipsychotics. Neuropsychobiology 2004, 49, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Désaméricq, G.; Schurhoff, F.; Meary, A.; Szöke, A.; Macquin-Mavier, I.; Bachoud-Lévi, A.C.; Maison, P. Long-term neurocognitive effects of antipsychotics in schizophrenia: A network meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Pharm. 2014, 70, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Liu, F.; Zu, Q.; Xu, Z.; Zheng, H.; Li, X.; Wang, W. Chronic administration of quetiapine attenuates the phencyclidine-induced recognition memory impairment and hippocampal oxidative stress in rats. Neuroreport 2018, 29, 1099–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aringhieri, S.; Carli, M.; Kolachalam, S.; Verdesca, V.; Cini, E.; Rossi, M.; McCormick, P.J.; Corsini, G.U.; Maggio, R.; Scarselli, M. Molecular targets of atypical antipsychotics: From mechanism of action to clinical differences. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 192, 20–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendouei, N.; Farnia, S.; Mohseni, F.; Salehi, A.; Bagheri, M.; Shadfar, F.; Barzegar, F.; Hoseini, S.D.; Charati, J.Y.; Shaki, F. Alterations in oxidative stress markers and its correlation with clinical findings in schizophrenic patients consuming perphenazine, clozapine and risperidone. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 103, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, M.J.; Sawa, A.; Mortensen, P.B. Schizophrenia. Lancet 2016, 388, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.R.; Cherian, J.; Gohil, K.; Atkinson, D. Schizophrenia: Overview and treatment options. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 39, 638–645. [Google Scholar]

- Mhillaj, E.; Morgese, M.G.; Trabace, L. Early life and oxidative stress in psychiatric disorders: What can we learn from animal models? Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015, 21, 1396–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, N.; Schwarz, M.J. Immune system and schizophrenia. Curr. Immunol. Rev. 2010, 6, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, K.; Egerton, A.; Kempton, M.J.; Taylor, M.J.; McGuire, P.K. Nature of glutamate alterations in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poels, E.M.; Kegeles, L.S.; Kantrowitz, J.T.; Slifstein, M.; Javitt, D.C.; Lieberman, J.A.; Abi-Dargham, A.; Girgis, R.R. Imaging glutamate in schizophrenia: Review of findings and implications for drug discovery. Mol. Psychiatry 2014, 19, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinton, S.M.; Meador-Woodruff, J.H. Abnormalities of the nmda receptor and associated intracellular molecules in the thalamus in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2004, 29, 1353–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiansen, L.V.; Beneyto, M.; Haroutunian, V.; Meador-Woodruff, J.H. Changes in nmda receptor subunits and interacting psd proteins in dorsolateral prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortex indicate abnormal regional expression in schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry 2006, 11, 705, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, C.; Deakin, J.F. Nmda receptor subunit nri and postsynaptic protein psd-95 in hippocampus and orbitofrontal cortex in schizophrenia and mood disorder. Schizophr. Res. 2005, 80, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasetti, C.; Iasevoli, F.; Buonaguro, E.F.; De Berardis, D.; Fornaro, M.; Fiengo, A.L.; Martinotti, G.; Orsolini, L.; Valchera, A.; Di Giannantonio, M.; et al. Treating the synapse in major psychiatric disorders: The role of postsynaptic density network in dopamine-glutamate interplay and psychopharmacologic drugs molecular actions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnuma, T.; Kato, H.; Arai, H.; Faull, R.L.; McKenna, P.J.; Emson, P.C. Gene expression of psd95 in prefrontal cortex and hippocampus in schizophrenia. Neuroreport 2000, 11, 3133–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dracheva, S.; Marras, S.A.; Elhakem, S.L.; Kramer, F.R.; Davis, K.L.; Haroutunian, V. N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor expression in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of elderly patients with schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 1400–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinton, S.M.; Haroutunian, V.; Meador-Woodruff, J.H. Up-regulation of nmda receptor subunit and post-synaptic density protein expression in the thalamus of elderly patients with schizophrenia. J. Neurochem. 2006, 98, 1114–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinton, S.M.; Haroutunian, V.; Davis, K.L.; Meador-Woodruff, J.H. Altered transcript expression of nmda receptor-associated postsynaptic proteins in the thalamus of subjects with schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 2003, 160, 1100–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, A.A. Dysregulation of the dopamine system in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and depression. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeman, P. Schizophrenia and dopamine receptors. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013, 23, 999–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, Y.; Kanahara, N.; Iyo, M. Alterations of dopamine d2 receptors and related receptor-interacting proteins in schizophrenia: The pivotal position of dopamine supersensitivity psychosis in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 30144–30163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Snyder, G.L.; Vanover, K.E. Dopamine targeting drugs for the treatment of schizophrenia: Past, present and future. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 3385–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo, A.N.; de Sena, E.P.; de Oliveira, I.R.; Juruena, M.F. Antipsychotic agents: Efficacy and safety in schizophrenia. Drug Healthc. Patient Saf. 2012, 4, 173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Caraci, F.; Leggio, G.M.; Salomone, S.; Drago, F. New drugs in psychiatry: Focus on new pharmacological targets. F1000Research 2017, 6, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitanihirwe, B.K.; Woo, T.U. Oxidative stress in schizophrenia: An integrated approach. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2011, 35, 878–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, H.G.; Keilhoff, G.; Steiner, J.; Dobrowolny, H.; Bogerts, B. Nitric oxide and schizophrenia: Present knowledge and emerging concepts of therapy. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2011, 10, 792–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallak, J.E.; Maia-de-Oliveira, J.P.; Abrao, J.; Evora, P.R.; Zuardi, A.W.; Crippa, J.A.; Belmonte-de-Abreu, P.; Baker, G.B.; Dursun, S.M. Rapid improvement of acute schizophrenia symptoms after intravenous sodium nitroprusside: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 668–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaulieu, J.M.; Gainetdinov, R.R. The physiology, signaling, and pharmacology of dopamine receptors. Pharm. Rev 2011, 63, 182–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishnoi, M.; Chopra, K.; Kulkarni, S.K. Co-administration of nitric oxide (no) donors prevents haloperidol-induced orofacial dyskinesia, oxidative damage and change in striatal dopamine levels. Pharm. Biochem. Behav. 2009, 91, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Valk, P.G.; Hollema, H.; van Voorst Vander, P.C.; Brinker, M.G.; Poppema, S. Sjögren’s syndrome with specific cutaneous manifestations and multifocal clonal t-cell populations progressing to a cutaneous pleomorphic t-cell lymphoma. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1989, 92, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapenna, A.; De Palma, M. Perivascular macrophages in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 689–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, N. Inflammation in schizophrenia: Pathogenetic aspects and therapeutic considerations. Schizophr. Bull. 2018, 44, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, J.; Nutma, E.; van der Valk, P.; Amor, S. Inflammation in CNS neurodegenerative diseases. Immunology 2018, 154, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Réus, G.Z.; Fries, G.R.; Stertz, L.; Badawy, M.; Passos, I.C.; Barichello, T.; Kapczinski, F.; Quevedo, J. The role of inflammation and microglial activation in the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders. Neuroscience 2015, 300, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.J.; Buckley, P.; Seabolt, W.; Mellor, A.; Kirkpatrick, B. Meta-analysis of cytokine alterations in schizophrenia: Clinical status and antipsychotic effects. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 70, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orsolini, L.; Sarchione, F.; Vellante, F.; Fornaro, M.; Matarazzo, I.; Martinotti, G.; Valchera, A.; Di Nicola, M.; Carano, A.; Di Giannantonio, M.; et al. Protein-c reactive as biomarker predictor of schizophrenia phases of illness? A systematic review. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 16, 583–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacomb, I.; Stanton, C.; Vasudevan, R.; Powell, H.; O’Donnell, M.; Lenroot, R.; Bruggemann, J.; Balzan, R.; Galletly, C.; Liu, D.; et al. C-reactive protein: Higher during acute psychotic episodes and related to cortical thickness in schizophrenia and healthy controls. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fond, G.; Lançon, C.; Auquier, P.; Boyer, L. C-reactive protein as a peripheral biomarker in schizophrenia. An updated systematic review. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.K.; Keshavan, M.S. Antioxidants, redox signaling, and pathophysiology in schizophrenia: An integrative view. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 15, 2011–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bounous, G.; Sukkar, S.; Molson, J. The antioxidant system. Anticancer Res. 2003, 23, 1411–1416. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Caruso, G.; Spampinato, S.F.; Cardaci, V.; Caraci, F.; Sortino, M.A.; Merlo, S. Β-amyloid and oxidative stress: Perspectives in drug development. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2019, 25, 4771–4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffa, M.; Mechri, A.; Othman, L.B.; Fendri, C.; Gaha, L.; Kerkeni, A. Decreased glutathione levels and antioxidant enzyme activities in untreated and treated schizophrenic patients. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 33, 1178–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawryluk, J.W.; Wang, J.F.; Andreazza, A.C.; Shao, L.; Young, L.T. Decreased levels of glutathione, the major brain antioxidant, in post-mortem prefrontal cortex from patients with psychiatric disorders. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011, 14, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabungcal, J.H.; Counotte, D.S.; Lewis, E.; Tejeda, H.A.; Piantadosi, P.; Pollock, C.; Calhoon, G.G.; Sullivan, E.; Presgraves, E.; Kil, J.; et al. Juvenile antioxidant treatment prevents adult deficits in a developmental model of schizophrenia. Neuron 2014, 83, 1073–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.K.; Leonard, S.; Reddy, R. Altered glutathione redox state in schizophrenia. Dis. Markers 2006, 22, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nucifora, L.G.; Tanaka, T.; Hayes, L.N.; Kim, M.; Lee, B.J.; Matsuda, T.; Nucifora, F.C., Jr.; Sedlak, T.; Mojtabai, R.; Eaton, W.; et al. Reduction of plasma glutathione in psychosis associated with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in translational psychiatry. Transl. Psychiatry 2017, 7, e1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.K.; Reddy, R.; van Kammen, D.P. Abnormal age-related changes of plasma antioxidant proteins in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2000, 97, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, R.; Keshavan, M.; Yao, J.K. Reduced plasma antioxidants in first-episode patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2003, 62, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakhale, G.; Khanzode, S.; Khanzode, S.; Saoji, A. Supplementation of vitamin c with atypical antipsychotics reduces oxidative stress and improves the outcome of schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology 2005, 182, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCreadie, R.G.; MacDonald, E.; Wiles, D.; Campbell, G.; Paterson, J.R. The nithsdale schizophrenia surveys. Xiv: Plasma lipid peroxide and serum vitamin e levels in patients with and without tardive dyskinesia, and in normal subjects. Br. J. Psychiatry 1995, 167, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Chen, D.C.; Xiu, M.H.; Wang, F.; Qi, L.Y.; Sun, H.Q.; Chen, S.; He, S.C.; Wu, G.Y.; Haile, C.N.; et al. The novel oxidative stress marker thioredoxin is increased in first-episode schizophrenic patients. Schizophr. Res. 2009, 113, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bas, A.; Gultekin, G.; Incir, S.; Bas, T.O.; Emul, M.; Duran, A. Level of serum thioredoxin and correlation with neurocognitive functions in patients with schizophrenia using clozapine and other atypical antipsychotics. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 247, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, T.M.; Thome, J.; Martin, D.; Nara, K.; Zwerina, S.; Tatschner, T.; Weijers, H.G.; Koutsilieri, E. Cu, Zn- and Mn-superoxide dismutase levels in brains of patients with schizophrenic psychosis. J. Neural Transm. (Vienna) 2004, 111, 1191–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Andreazza, A.C.; Yeung, P.Y.; Isaacs-Trepanier, C.; Young, L.T. Oxidation and nitration in dopaminergic areas of the prefrontal cortex from patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2014, 39, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First-Generation Antipsychotics: An Introduction. Available online: https://psychopharmacologyinstitute.com/publication/first-generation-antipsychotics-an-introduction-2110 (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Trollor, J.N.; Chen, X.; Chitty, K.; Sachdev, P.S. Comparison of neuroleptic malignant syndrome induced by first- and second-generation antipsychotics. Br. J. Psychiatry 2012, 201, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chackupurakal, R.; Wild, U.; Kamm, M.; Wappler, F.; Reske, D.; Sakka, S.G. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: Rare cause of fever of unknown origin. Anaesthesist 2015, 64, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadet, J.L.; Lohr, J.B. Possible involvement of free radicals in neuroleptic-induced movement disorders. Evidence from treatment of tardive dyskinesia with vitamin e. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1989, 570, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, K.; Reid, A.; White, T.; Henderson, T.; Hukin, S.; Johnstone, C.; Glen, A. Vitamin e, lipids, and lipid peroxidation products in tardive dyskinesia. Biol. Psychiatry 1998, 43, 863–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropp, S.; Kern, V.; Lange, K.; Degner, D.; Hajak, G.; Kornhuber, J.; Rüther, E.; Emrich, H.M.; Schneider, U.; Bleich, S. Oxidative stress during treatment with first- and second-generation antipsychotics. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2005, 17, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Muñoz, F.; Alamo, C. The consolidation of neuroleptic therapy: Janssen, the discovery of haloperidol and its introduction into clinical practice. Brain Res. Bull. 2009, 79, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dold, M.; Samara, M.T.; Li, C.; Tardy, M.; Leucht, S. Haloperidol versus first-generation antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev 2015, 1, Cd009831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanyam, B.; Rollema, H.; Woolf, T.; Castagnoli, N., Jr. Identification of a potentially neurotoxic pyridinium metabolite of haloperidol in rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1990, 166, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrallah, H.A.; Chen, A.T. Multiple neurotoxic effects of haloperidol resulting in neuronal death. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 2017, 29, 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Gassó, P.; Mas, S.; Molina, O.; Bernardo, M.; Lafuente, A.; Parellada, E. Neurotoxic/neuroprotective activity of haloperidol, risperidone and paliperidone in neuroblastoma cells. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2012, 36, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, I.J.; Cooper, A.C.; Griffiths, M.R.; Cooper, A.J. Acute administration of haloperidol induces apoptosis of neurones in the striatum and substantia nigra in the rat. Neuroscience 2002, 109, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, A.; Veeranan-Karmegam, R.; Dhandapani, K.M.; Mahadik, S.P. Cystamine prevents haloperidol-induced decrease of bdnf/trkb signaling in mouse frontal cortex. J. Neurochem. 2008, 107, 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Salam, O.M.; El-Sayed El-Shamarka, M.; Salem, N.A.; El-Mosallamy, A.E.; Sleem, A.A. Amelioration of the haloperidol-induced memory impairment and brain oxidative stress by cinnarizine. EXCLI J. 2012, 11, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Trevizol, F.; Benvegnú, D.M.; Barcelos, R.C.; Pase, C.S.; Segat, H.J.; Dias, V.T.; Dolci, G.S.; Boufleur, N.; Reckziegel, P.; Bürger, M.E. Comparative study between two animal models of extrapyramidal movement disorders: Prevention and reversion by pecan nut shell aqueous extract. Behav. Brain Res. 2011, 221, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samad, N.; Haleem, D.J. Antioxidant effects of rice bran oil mitigate repeated haloperidol-induced tardive dyskinesia in male rats. Metab. Brain Dis. 2017, 32, 1099–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, T.; Maruoka, N.; Omata, N.; Takashima, Y.; Igarashi, K.; Kasuya, F.; Fujibayashi, Y.; Wada, Y. Effects of haloperidol and its pyridinium metabolite on plasma membrane permeability and fluidity in the rat brain. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2007, 31, 848–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bošković, M.; Vovk, T.; Kores Plesničar, B.; Grabnar, I. Oxidative stress in schizophrenia. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2011, 9, 301–312. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenska, M.; Gumulec, J.; Babula, P.; Stracina, T.; Sztalmachova, M.; Polanska, H.; Adam, V.; Kizek, R.; Novakova, M.; Masarik, M. Haloperidol cytotoxicity and its relation to oxidative stress. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2013, 13, 1993–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quincozes-Santos, A.; Bobermin, L.D.; Tonial, R.P.; Bambini-Junior, V.; Riesgo, R.; Gottfried, C. Effects of atypical (risperidone) and typical (haloperidol) antipsychotic agents on astroglial functions. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2010, 260, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukai, W.; Ozawa, H.; Tateno, M.; Hashimoto, E.; Saito, T. Neurotoxic potential of haloperidol in comparison with risperidone: Implication of akt-mediated signal changes by haloperidol. J. Neural Transm. (Vienna) 2004, 111, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, C.; Lezoualc’h, F.; Widmann, M.; Rupprecht, R.; Holsboer, F. Oxidative stress-resistant cells are protected against haloperidol toxicity. Brain Res. 1996, 717, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, A.; Holsboer, F.; Behl, C. Induction of nf-κb activity during haloperidol-induced oxidative toxicity in clonal hippocampal cells: Suppression of nf-κb and neuroprotection by antioxidants. J. Neurosci. 1998, 18, 8236–8246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Lee, J.-H.; El-Fakahany, E.E. Inhibition of neuronal nitric oxide synthase by antipsychotic drugs. Psychopharmacology 1994, 114, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinke, A.; Martins, M.R.; Lima, M.S.; Moreira, J.C.; Dal-Pizzol, F.; Quevedo, J. Haloperidol and clozapine, but not olanzapine, induces oxidative stress in rat brain. Neurosci. Lett. 2004, 372, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, K.S.; Prakash, A.; Bisht, R.; Bansal, P.K. Beneficial effect of candesartan and lisinopril against haloperidol-induced tardive dyskinesia in rat. J. Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2015, 16, 917–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiser, P.; Sommer, O.; Schmidt, A.J.; Clement, H.W.; Hoinkes, A.; Hopt, U.T.; Schulz, E.; Krieg, J.C.; Dobschütz, E. Effects of antipsychotics and vitamin c on the formation of reactive oxygen species. J. Psychopharmacol. 2010, 24, 1499–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumulec, J.; Raudenska, M.; Hlavna, M.; Stracina, T.; Sztalmachova, M.; Tanhauserova, V.; Pacal, L.; Ruttkay-Nedecky, B.; Sochor, J.; Zitka, O.; et al. Determination of oxidative stress and activities of antioxidant enzymes in guinea pigs treated with haloperidol. Exp. Med. 2013, 5, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreazza, A.C.; Barakauskas, V.E.; Fazeli, S.; Feresten, A.; Shao, L.; Wei, V.; Wu, C.H.; Barr, A.M.; Beasley, C.L. Effects of haloperidol and clozapine administration on oxidative stress in rat brain, liver and serum. Neurosci. Lett. 2015, 591, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvindakshan, M.; Sitasawad, S.; Debsikdar, V.; Ghate, M.; Evans, D.; Horrobin, D.F.; Bennett, C.; Ranjekar, P.K.; Mahadik, S.P. Essential polyunsaturated fatty acid and lipid peroxide levels in never-medicated and medicated schizophrenia patients. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 53, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamińska, T.; Szuster-Ciesielska, A.; Wysocka, A.; Marmurowska-Michałowska, H.; Dubas-Slemp, H.; Kandefer-Szerszeń, M. Serum cytokine level and production of reactive oxygen species (ros) by blood neutrophils from a schizophrenic patient with hypersensitivity to neuroleptics. Med. Sci. Monit. 2003, 9, Cs71–Cs75. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, O.P.; Chakraborty, I.; Dasgupta, A.; Datta, S. A comparative study of oxidative stress and interrelationship of important antioxidants in haloperidol and olanzapine treated patients suffering from schizophrenia. Indian J. Psychiatry 2008, 50, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, J.A.; Tollefson, G.D.; Charles, C.; Zipursky, R.; Sharma, T.; Kahn, R.S.; Keefe, R.S.; Green, A.I.; Gur, R.E.; McEvoy, J. Antipsychotic drug effects on brain morphology in first-episode psychosis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strungas, S.; Christensen, J.D.; Holcomb, J.M.; Garver, D.L. State-related thalamic changes during antipsychotic treatment in schizophrenia: Preliminary observations. Psychiatry Res. 2003, 124, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dazzan, P.; Morgan, K.D.; Orr, K.; Hutchinson, G.; Chitnis, X.; Suckling, J.; Fearon, P.; McGuire, P.K.; Mallett, R.M.; Jones, P.B.; et al. Different effects of typical and atypical antipsychotics on grey matter in first episode psychosis: The aesop study. Neuropsychopharmacology 2005, 30, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, E.J.; Wolkin, A.; Brodie, J.D.; Laska, E.M.; Wolf, A.P.; Sanfilipo, M. Importance of pharmacologic control in pet studies: Effects of thiothixene and haloperidol on cerebral glucose utilization in chronic schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1991, 40, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.D.; Andreasen, N.C.; O’Leary, D.S.; Watkins, G.L.; Boles Ponto, L.L.; Hichwa, R.D. Comparison of the effects of risperidone and haloperidol on regional cerebral blood flow in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 2001, 49, 704–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Zhou, D.F.; Shen, Y.C.; Zhang, P.Y.; Zhang, W.F.; Liang, J.; Chen, D.C.; Xiu, M.H.; Kosten, T.A.; Kosten, T.R. Effects of risperidone and haloperidol on superoxide dismutase and nitric oxide in schizophrenia. Neuropharmacology 2012, 62, 1928–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Tan, Y.L.; Cao, L.Y.; Wu, G.Y.; Xu, Q.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, D.F. Antioxidant enzymes and lipid peroxidation in different forms of schizophrenia treated with typical and atypical antipsychotics. Schizophr. Res. 2006, 81, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeman, P. Atypical antipsychotics: Mechanism of action. Can. J. Psychiatry 2002, 47, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jann, M.W. Implications for atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: Neurocognition effects and a neuroprotective hypothesis. Pharmacotherapy 2004, 24, 1759–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandra, K.S.; Agius, M. The differences between typical and atypical antipsychotics: The effects on neurogenesis. Psychiatr. Danub. 2012, 24 (Suppl. 1), S95–S99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Amin, M.M.; Nasir Uddin, M.M.; Mahmud Reza, H. Effects of antipsychotics on the inflammatory response system of patients with schizophrenia in peripheral blood mononuclear cell cultures. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2013, 11, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noto, C.; Ota, V.K.; Gouvea, E.S.; Rizzo, L.B.; Spindola, L.M.; Honda, P.H.; Cordeiro, Q.; Belangero, S.I.; Bressan, R.A.; Gadelha, A.; et al. Effects of risperidone on cytokine profile in drug-naïve first-episode psychosis. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tendilla-Beltrán, H.; Meneses-Prado, S.; Vázquez-Roque, R.A.; Tapia-Rodríguez, M.; Vázquez-Hernández, A.J.; Coatl-Cuaya, H.; Martín-Hernández, D.; MacDowell, K.S.; Garcés-Ramírez, L.; Leza, J.C.; et al. Risperidone ameliorates prefrontal cortex neural atrophy and oxidative/nitrosative stress in brain and peripheral blood of rats with neonatal ventral hippocampus lesion. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 8584–8599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casquero-Veiga, M.; García-García, D.; MacDowell, K.S.; Pérez-Caballero, L.; Torres-Sánchez, S.; Fraguas, D.; Berrocoso, E.; Leza, J.C.; Arango, C.; Desco, M.; et al. Risperidone administered during adolescence induced metabolic, anatomical and inflammatory/oxidative changes in adult brain: A pet and mri study in the maternal immune stimulation animal model. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019, 29, 880–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojković, T.; Radonjić, N.V.; Velimirović, M.; Jevtić, G.; Popović, V.; Doknić, M.; Petronijević, N.D. Risperidone reverses phencyclidine induced decrease in glutathione levels and alterations of antioxidant defense in rat brain. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2012, 39, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flatow, J.; Buckley, P.; Miller, B.J. Meta-analysis of oxidative stress in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 74, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Zhou, D.F.; Cao, L.Y.; Zhang, P.Y.; Wu, G.Y.; Shen, Y.C. The effect of risperidone treatment on superoxide dismutase in schizophrenia. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2003, 23, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerin Khan, F.; Sultana, S.P.; Akhter, N.; Mosaddek, A.S.M. Effect of olanzapine and risperidone on oxidative stress in schizophrenia patients. Int. Biol. Biomed. J. 2018, 4, 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich-Muszalska, A.; Kopka, J.; Kwiatkowska, A. The effects of ziprasidone, clozapine and haloperidol on lipid peroxidation in human plasma (in vitro): Comparison. Neurochem. Res. 2013, 38, 1490–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, O.; Chlan-Fourney, J.; Bowen, R.; Keegan, D.; Li, X.M. Expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mrna in rat hippocampus after treatment with antipsychotic drugs. J. Neurosci. Res. 2003, 71, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedrini, M.; Chendo, I.; Grande, I.; Lobato, M.I.; Belmonte-de-Abreu, P.S.; Lersch, C.; Walz, J.; Kauer-Sant’anna, M.; Kapczinski, F.; Gama, C.S. Serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor and clozapine daily dose in patients with schizophrenia: A positive correlation. Neurosci. Lett. 2011, 491, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.T.; Nasrallah, H.A. Neuroprotective effects of the second generation antipsychotics. Schizophr. Res. 2019, 208, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fumagalli, F.; Frasca, A.; Racagni, G.; Riva, M.A. Antipsychotic drugs modulate arc expression in the rat brain. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009, 19, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freyberg, Z.; Ferrando, S.J.; Javitch, J.A. Roles of the akt/gsk-3 and wnt signaling pathways in schizophrenia and antipsychotic drug action. Am. J. Psychiatry 2010, 167, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Bai, O.; Richardson, J.S.; Mousseau, D.D.; Li, X.M. Olanzapine protects pc12 cells from oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide. J. Neurosci. Res. 2003, 73, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Chalabi, B.M.; Thanoon, I.A.; Ahmed, F.A. Potential effect of olanzapine on total antioxidant status and lipid peroxidation in schizophrenic patients. Neuropsychobiology 2009, 59, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinholi, F.F.; Farias, C.C.; Bonifácio, K.L.; Higachi, L.; Casagrande, R.; Moreira, E.G.; Barbosa, D.S. Clozapine and olanzapine are better antioxidants than haloperidol, quetiapine, risperidone and ziprasidone in in vitro models. Biomed. Pharm. 2016, 81, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribaudo, G.; Bortoli, M.; Pavan, C.; Zagotto, G.; Orian, L. Antioxidant potential of psychotropic drugs: From clinical evidence to in vitro and in vivo assessment and toward a new challenge for in silico molecular design. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowska-Bartosz, I.; Galiniak, S.; Bartosz, G.; Zuberek, M.; Grzelak, A.; Dietrich-Muszalska, A. Antioxidant properties of atypical antipsychotic drugs used in the treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2016, 176, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, V.; Khan, M.M.; Mahadik, S.P. Differential effects of antipsychotics on expression of antioxidant enzymes and membrane lipid peroxidation in rat brain. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2003, 37, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich-Muszalska, A.; Kolińska-Łukaszuk, J. Comparative effects of aripiprazole and selected antipsychotic drugs on lipid peroxidation in plasma. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 72, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mailman, R.B.; Murthy, V. Third generation antipsychotic drugs: Partial agonism or receptor functional selectivity? Curr. Pharm. Des. 2010, 16, 488–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eren, I.; Naziroğlu, M.; Demirdaş, A. Protective effects of lamotrigine, aripiprazole and escitalopram on depression-induced oxidative stress in rat brain. Neurochem. Res. 2007, 32, 1188–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huh, L.; Lee, B.J. Efficacy of low-dose aripiprazole to treat clozapine-associated tardive dystonia in a patient with schizophrenia. Turk Psikiyatr. Derg. 2017, 28, 208–211. [Google Scholar]

- Machado-Vieira, R.; Andreazza, A.C.; Viale, C.I.; Zanatto, V.; Cereser, V., Jr.; da Silva Vargas, R.; Kapczinski, F.; Portela, L.V.; Souza, D.O.; Salvador, M.; et al. Oxidative stress parameters in unmedicated and treated bipolar subjects during initial manic episode: A possible role for lithium antioxidant effects. Neurosci. Lett. 2007, 421, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.H.; Yan, B.C.; Park, J.H.; Ahn, J.H.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, I.H.; Cho, J.-H.; Lee, J.-C.; Kim, S.K.; Lee, B. Aripiprazole, an atypical antipsychotic drug, improves maturation and complexity of neuroblast dendrites in the mouse dentate gyrus via increasing superoxide dismutases. Neurochem. Res. 2013, 38, 1980–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, N.; Vernuccio, F.; Costantino, C.; Imburgia, C.; Gregoretti, C.; Salomone, S.; Drago, F.; Lo Bianco, G. An italian guidance model for the management of suspected or confirmed covid-19 patients in the primary care setting. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baqi, H.R.; Farag, H.A.M.; El Bilbeisi, A.H.H.; Askandar, R.H.; El Afifi, A.M. Oxidative stress and its association with covid-19: A narrative review. Kurd. J. Appl. Res. 2020, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossù, P.; Toppi, E.; Sterbini, V.; Spalletta, G. Implication of aging related chronic neuroinflammation on covid-19 pandemic. J. Pers. Med. 2020, 10, 102. [Google Scholar]

- Martinotti, G.; Barlati, S.; Prestia, D.; Palumbo, C.; Giordani, M.; Cuomo, A.; Miuli, A.; Paladini, C.; Amore, M.; Bondi, E.; et al. Psychomotor agitation and hyperactive delirium in covid-19 patients treated with aripiprazole 9.75 mg/1.3 mL immediate release. Psychopharmacolology (Berl) 2020, 237, 3497–3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostuzzi, G.; Gastaldon, C.; Papola, D.; Fagiolini, A.; Dursun, S.; Taylor, D.; Correll, C.U.; Barbui, C. Pharmacological treatment of hyperactive delirium in people with covid-19: Rethinking conventional approaches. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 10, 2045125320942703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiavone, S.; Trabace, L. The use of antioxidant compounds in the treatment of first psychotic episode: Highlights from preclinical studies. CNS Neurosci. 2018, 24, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanepoel, T.; Möller, M.; Harvey, B.H. N-acetyl cysteine reverses bio-behavioural changes induced by prenatal inflammation, adolescent methamphetamine exposure and combined challenges. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2018, 235, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phensy, A.; Driskill, C.; Lindquist, K.; Guo, L.; Jeevakumar, V.; Fowler, B.; Du, H.; Kroener, S. Antioxidant treatment in male mice prevents mitochondrial and synaptic changes in an nmda receptor dysfunction model of schizophrenia. eNeuro 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, P.V.; Dean, O.; Andreazza, A.C.; Berk, M.; Kapczinski, F. Antioxidant treatments for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2, Cd008919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firth, J.; Rosenbaum, S.; Ward, P.B.; Curtis, J.; Teasdale, S.B.; Yung, A.R.; Sarris, J. Adjunctive nutrients in first-episode psychosis: A systematic review of efficacy, tolerability and neurobiological mechanisms. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2018, 12, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.L.; Bennett, F.C. The influence of environment and origin on brain resident macrophages and implications for therapy. Nat. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solleiro-Villavicencio, H.; Rivas-Arancibia, S. Effect of chronic oxidative stress on neuroinflammatory response mediated by cd4(+)t cells in neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, H.; Hafizi, S.; Andreazza, A.C.; Mizrahi, R. Neuroinflammation and oxidative stress in psychosis and psychosis risk. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monji, A.; Kato, T.; Kanba, S. Cytokines and schizophrenia: Microglia hypothesis of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2009, 63, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howes, O.D.; McCutcheon, R. Inflammation and the neural diathesis-stress hypothesis of schizophrenia: A reconceptualization. Transl. Psychiatry 2017, 7, e1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDowell, K.S.; Caso, J.R.; Martín-Hernández, D.; Moreno, B.M.; Madrigal, J.L.M.; Micó, J.A.; Leza, J.C.; García-Bueno, B. The atypical antipsychotic paliperidone regulates endogenous antioxidant/anti-inflammatory pathways in rat models of acute and chronic restraint stress. Neurotherapeutics 2016, 13, 833–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, T.A.; Monji, A.; Yasukawa, K.; Mizoguchi, Y.; Horikawa, H.; Seki, Y.; Hashioka, S.; Han, Y.H.; Kasai, M.; Sonoda, N.; et al. Aripiprazole inhibits superoxide generation from phorbol-myristate-acetate (pma)-stimulated microglia in vitro: Implication for antioxidative psychotropic actions via microglia. Schizophr. Res. 2011, 129, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Mizoguchi, Y.; Monji, A.; Horikawa, H.; Suzuki, S.O.; Seki, Y.; Iwaki, T.; Hashioka, S.; Kanba, S. Inhibitory effects of aripiprazole on interferon-gamma-induced microglial activation via intracellular ca2+ regulation in vitro. J. Neurochem. 2008, 106, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasyrova, R.F.; Ivashchenko, D.V.; Ivanov, M.V.; Neznanov, N.G. Role of nitric oxide and related molecules in schizophrenia pathogenesis: Biochemical, genetic and clinical aspects. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Monji, A.; Hashioka, S.; Kanba, S. Risperidone significantly inhibits interferon-gamma-induced microglial activation in vitro. Schizophr. Res. 2007, 92, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDowell, K.S.; García-Bueno, B.; Madrigal, J.L.; Parellada, M.; Arango, C.; Micó, J.A.; Leza, J.C. Risperidone normalizes increased inflammatory parameters and restores anti-inflammatory pathways in a model of neuroinflammation. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013, 16, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Zheng, Y.; Ding, Y.Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wu, R.; Guo, X.; Zhao, J. Minocycline and risperidone prevent microglia activation and rescue behavioral deficits induced by neonatal intrahippocampal injection of lipopolysaccharide in rats. PloS ONE 2014, 9, e93966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandes, M.S.; Britto, L.R. Nadph oxidase and neurodegeneration. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2012, 10, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Kim, J.; Song, J.H. Clozapine and olanzapine inhibit proton currents in bv2 microglial cells. Eur. J. Pharm. 2015, 755, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Möller, M.; Du Preez, J.L.; Emsley, R.; Harvey, B.H. Isolation rearing-induced deficits in sensorimotor gating and social interaction in rats are related to cortico-striatal oxidative stress, and reversed by sub-chronic clozapine administration. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011, 21, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, D.; Yang, S.; Qian, L.; Wu, H.M.; Chen, P.S.; Wilson, B.; Gao, H.M.; Lu, R.B.; et al. Clozapine protects dopaminergic neurons from inflammation-induced damage by inhibiting microglial overactivation. J. Neuroimmune Pharm. 2012, 7, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Wu, X.; Wang, S.; Chen, S.H.; Zhou, H.; Wilson, B.; Jin, C.Y.; Lu, R.B.; Xie, K.; Wang, Q.; et al. Clozapine metabolites protect dopaminergic neurons through inhibition of microglial nadph oxidase. J. Neuroinflammation 2016, 13, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, B.M.; do Carmo, M.R.; Freire, R.S.; Rocha, N.F.; Borella, V.C.; de Menezes, A.T.; Monte, A.S.; Gomes, P.X.; de Sousa, F.C.; Vale, M.L.; et al. Evidences for a progressive microglial activation and increase in inos expression in rats submitted to a neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia: Reversal by clozapine. Schizophr. Res. 2013, 151, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caruso, G.; Grasso, M.; Fidilio, A.; Tascedda, F.; Drago, F.; Caraci, F. Antioxidant Properties of Second-Generation Antipsychotics: Focus on Microglia. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph13120457

Caruso G, Grasso M, Fidilio A, Tascedda F, Drago F, Caraci F. Antioxidant Properties of Second-Generation Antipsychotics: Focus on Microglia. Pharmaceuticals. 2020; 13(12):457. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph13120457

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaruso, Giuseppe, Margherita Grasso, Annamaria Fidilio, Fabio Tascedda, Filippo Drago, and Filippo Caraci. 2020. "Antioxidant Properties of Second-Generation Antipsychotics: Focus on Microglia" Pharmaceuticals 13, no. 12: 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph13120457

APA StyleCaruso, G., Grasso, M., Fidilio, A., Tascedda, F., Drago, F., & Caraci, F. (2020). Antioxidant Properties of Second-Generation Antipsychotics: Focus on Microglia. Pharmaceuticals, 13(12), 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph13120457