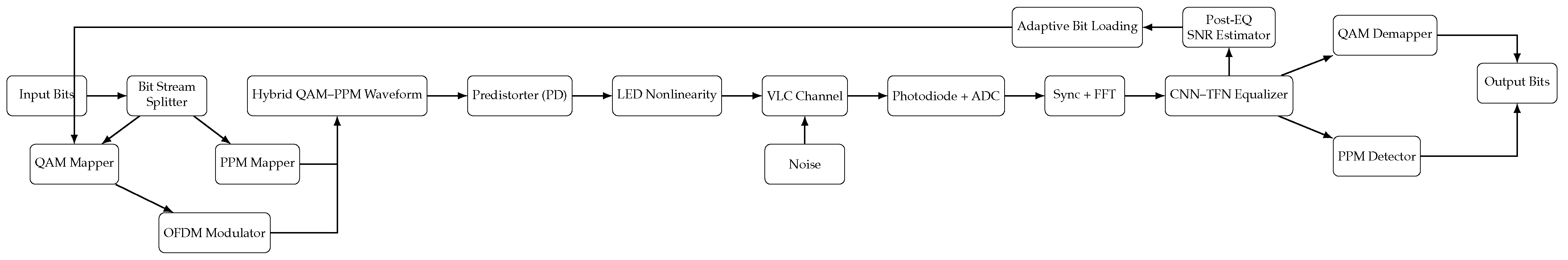

Figure 1.

System-level block diagram of the proposed hybrid QAM–PPM VLC–OFDM framework. Hybrid modulation and predistortion are applied at the transmitter, CNN–TFN equalization compensates channel and hardware impairments at the receiver, and adaptive bit loading adjusts the QAM modulation order based on post-equalization SNR estimates.

Figure 1.

System-level block diagram of the proposed hybrid QAM–PPM VLC–OFDM framework. Hybrid modulation and predistortion are applied at the transmitter, CNN–TFN equalization compensates channel and hardware impairments at the receiver, and adaptive bit loading adjusts the QAM modulation order based on post-equalization SNR estimates.

Figure 2.

System architecture and hybrid modulation processing.

Figure 2.

System architecture and hybrid modulation processing.

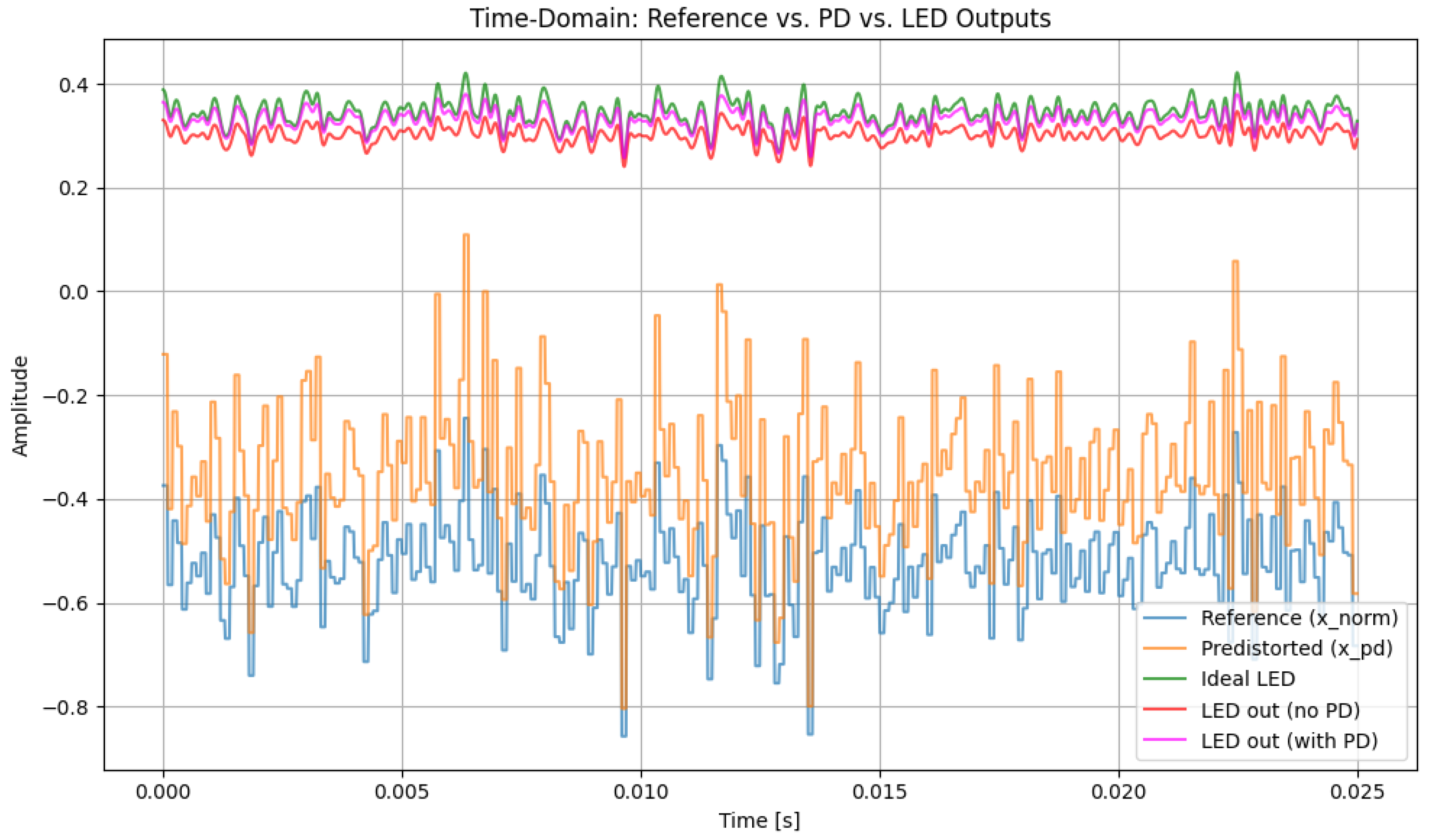

Figure 3.

Time-domain waveform analysis of the hybrid signal with 3rd-order PD and , illustrating the signal behavior under nonlinear distortion mitigation.

Figure 3.

Time-domain waveform analysis of the hybrid signal with 3rd-order PD and , illustrating the signal behavior under nonlinear distortion mitigation.

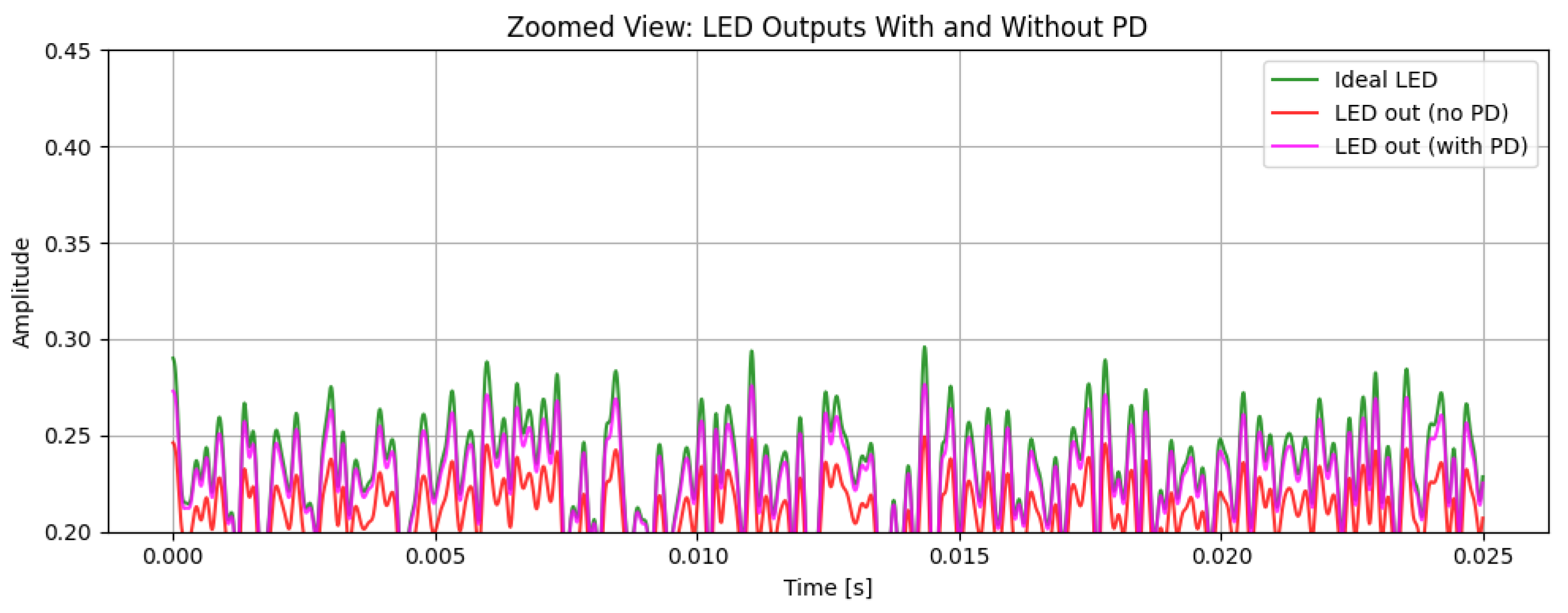

Figure 4.

Magnified image of the LED hybrid signal with 3rd-order PD and , illustrating the signal behavior under nonlinear distortion mitigation.

Figure 4.

Magnified image of the LED hybrid signal with 3rd-order PD and , illustrating the signal behavior under nonlinear distortion mitigation.

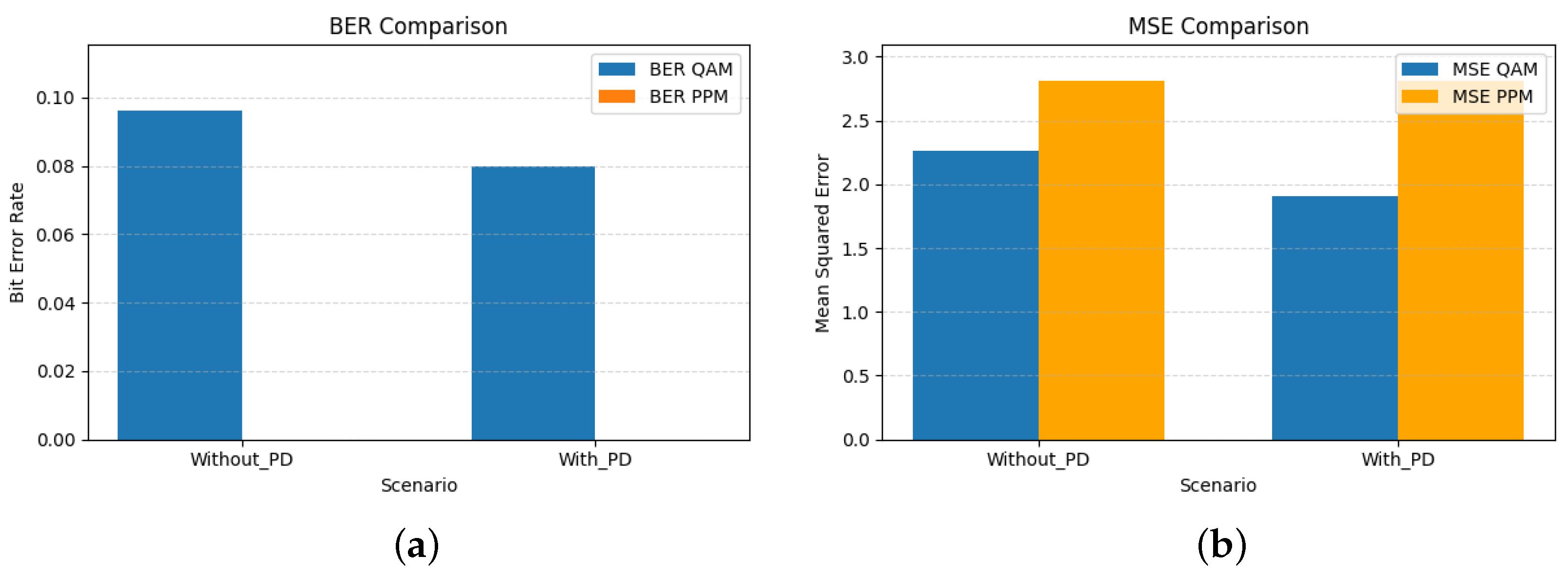

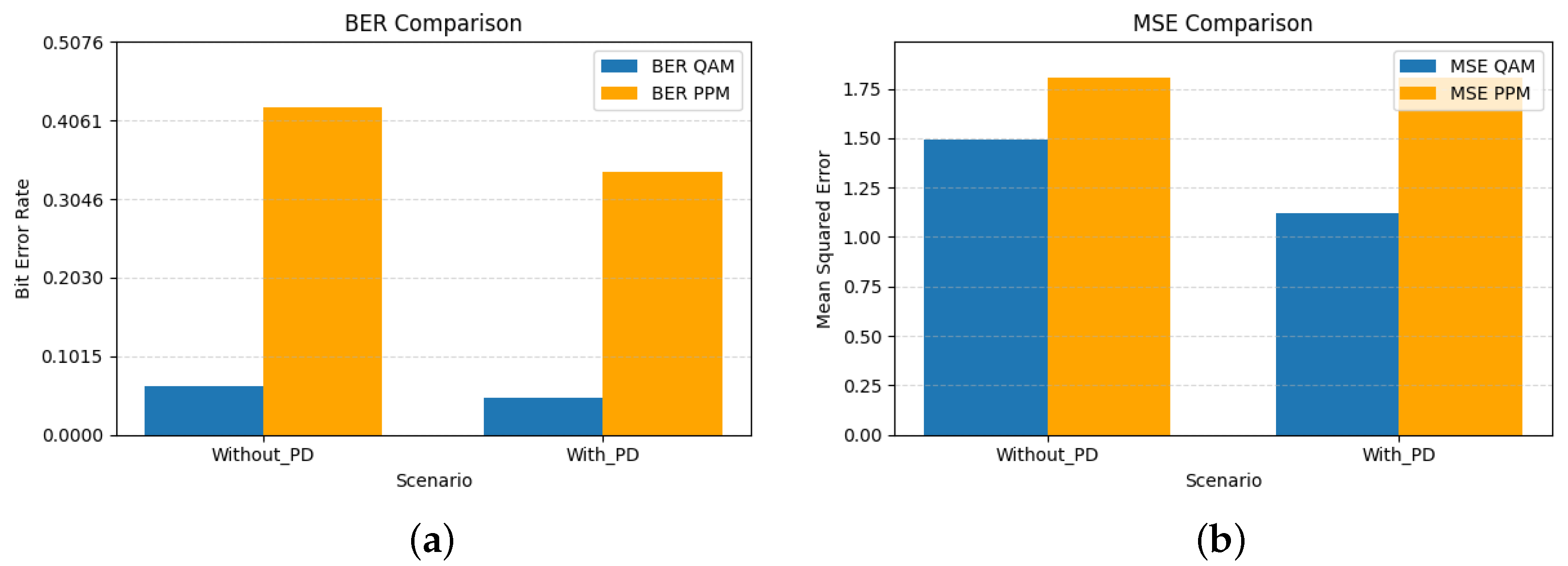

Figure 5.

(a) BER comparison and (b) MSE comparison for QAM and PPM signals with 3rd-order PD and . The results demonstrate the effectiveness of PD for nonlinear distortion mitigation in QAM signals, while PPM remains largely unaffected.

Figure 5.

(a) BER comparison and (b) MSE comparison for QAM and PPM signals with 3rd-order PD and . The results demonstrate the effectiveness of PD for nonlinear distortion mitigation in QAM signals, while PPM remains largely unaffected.

Figure 6.

Time-domain waveform analysis of the hybrid signal with 5th-order PD and . The increased PD order closely tracks the reference signal, improving QAM signal linearity.

Figure 6.

Time-domain waveform analysis of the hybrid signal with 5th-order PD and . The increased PD order closely tracks the reference signal, improving QAM signal linearity.

Figure 7.

Magnified image of the LED hybrid signal with 5th-order PD and , illustrating the signal behavior under nonlinear distortion mitigation.

Figure 7.

Magnified image of the LED hybrid signal with 5th-order PD and , illustrating the signal behavior under nonlinear distortion mitigation.

Figure 8.

(a) BER comparison and (b) MSE comparison for QAM and PPM signals with 5th-order PD and . Higher PD order improves QAM signal performance, while PPM remains unaffected.

Figure 8.

(a) BER comparison and (b) MSE comparison for QAM and PPM signals with 5th-order PD and . Higher PD order improves QAM signal performance, while PPM remains unaffected.

Figure 9.

Time-domain waveform analysis of the hybrid signal with 7th-order PD and , showing how the higher-order PD mitigates nonlinear distortions for both QAM and PPM signals.

Figure 9.

Time-domain waveform analysis of the hybrid signal with 7th-order PD and , showing how the higher-order PD mitigates nonlinear distortions for both QAM and PPM signals.

Figure 10.

Magnified image of the LED hybrid signal with 7th-order PD and , illustrating the signal behavior under nonlinear distortion mitigation.

Figure 10.

Magnified image of the LED hybrid signal with 7th-order PD and , illustrating the signal behavior under nonlinear distortion mitigation.

Figure 11.

(a) 16-QAM BER comparison and (b) MSE comparison for QAM and PPM signals with 7th-order PD and . The results demonstrate improvements in both QAM and PPM signal performance due to higher-order PD.

Figure 11.

(a) 16-QAM BER comparison and (b) MSE comparison for QAM and PPM signals with 7th-order PD and . The results demonstrate improvements in both QAM and PPM signal performance due to higher-order PD.

Figure 12.

Impact of PD order on the BER performance of the hybrid VLC system under strong LED nonlinearity (). Higher PD orders yield progressively lower BER for the QAM branch, with diminishing performance gains beyond the 5th order.

Figure 12.

Impact of PD order on the BER performance of the hybrid VLC system under strong LED nonlinearity (). Higher PD orders yield progressively lower BER for the QAM branch, with diminishing performance gains beyond the 5th order.

Figure 13.

BER performance for the QAM branch with pilot spacing of 8. Dense pilot insertion improves channel estimation accuracy, resulting in significantly lower BER compared to the no-pilot scenario both with and without predistortion.

Figure 13.

BER performance for the QAM branch with pilot spacing of 8. Dense pilot insertion improves channel estimation accuracy, resulting in significantly lower BER compared to the no-pilot scenario both with and without predistortion.

Figure 14.

MSE performance for the QAM branch with pilot spacing of 8. Pilot-assisted estimation substantially reduces symbol estimation error relative to the no-pilot case, demonstrating enhanced robustness with and without predistortion.

Figure 14.

MSE performance for the QAM branch with pilot spacing of 8. Pilot-assisted estimation substantially reduces symbol estimation error relative to the no-pilot case, demonstrating enhanced robustness with and without predistortion.

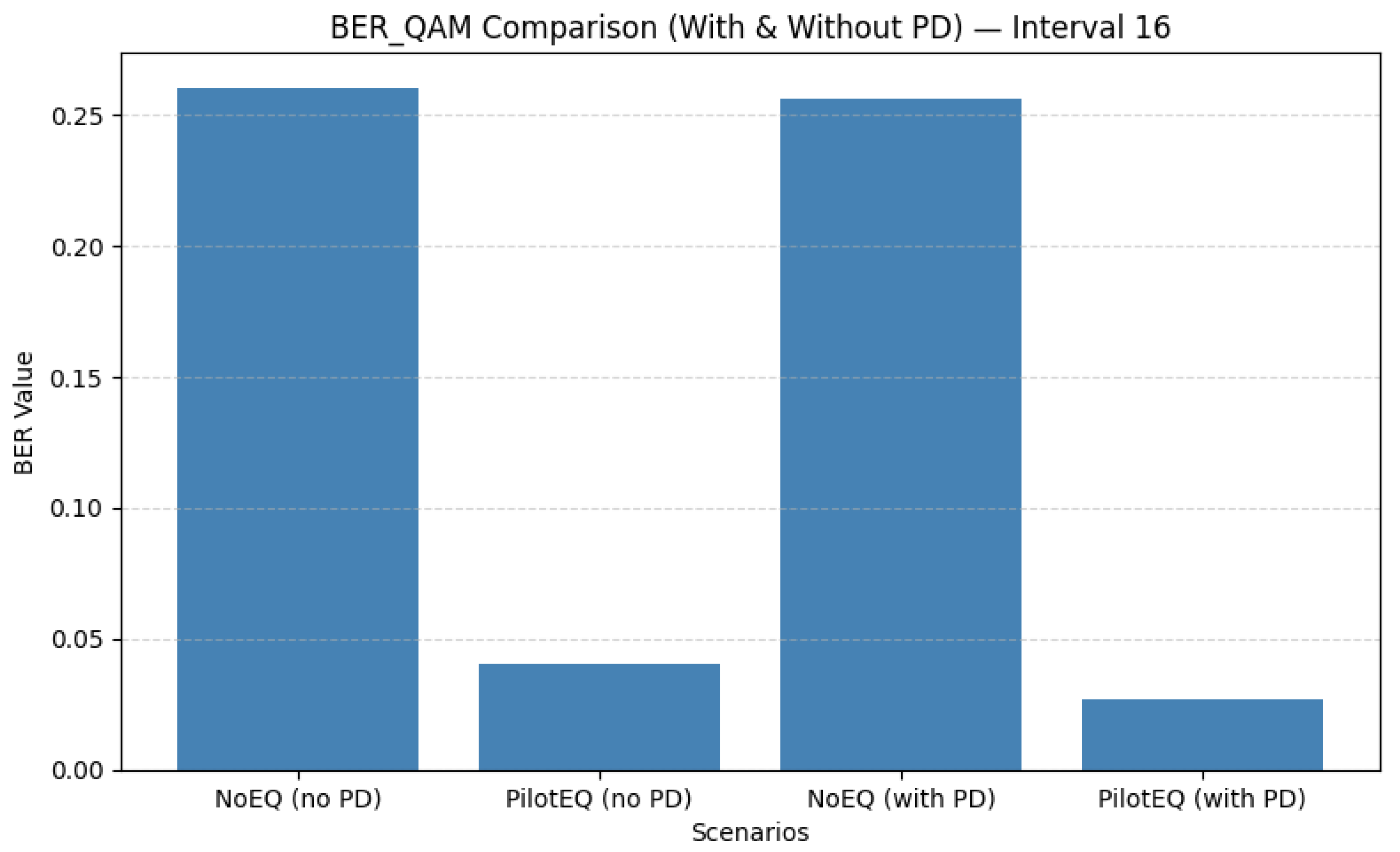

Figure 15.

BER performance for the QAM branch with pilot spacing of 16. Dense pilot insertion improves channel estimation accuracy, resulting in significantly lower BER compared to the no-pilot scenario both with and without predistortion.

Figure 15.

BER performance for the QAM branch with pilot spacing of 16. Dense pilot insertion improves channel estimation accuracy, resulting in significantly lower BER compared to the no-pilot scenario both with and without predistortion.

Figure 16.

MSE performance for the QAM branch with pilot spacing of 16. Pilot-assisted estimation substantially reduces symbol estimation error relative to the no-pilot case, demonstrating enhanced robustness with and without predistortion.

Figure 16.

MSE performance for the QAM branch with pilot spacing of 16. Pilot-assisted estimation substantially reduces symbol estimation error relative to the no-pilot case, demonstrating enhanced robustness with and without predistortion.

Figure 17.

BER performance for the QAM branch with pilot spacing of 24. Dense pilot insertion improves channel estimation accuracy, resulting in significantly lower BER compared to the no-pilot scenario both with and without predistortion.

Figure 17.

BER performance for the QAM branch with pilot spacing of 24. Dense pilot insertion improves channel estimation accuracy, resulting in significantly lower BER compared to the no-pilot scenario both with and without predistortion.

Figure 18.

MSE performance for the QAM branch with pilot spacing of 24. Pilot-assisted estimation substantially reduces symbol estimation error relative to the no-pilot case, demonstrating enhanced robustness with and without predistortion.

Figure 18.

MSE performance for the QAM branch with pilot spacing of 24. Pilot-assisted estimation substantially reduces symbol estimation error relative to the no-pilot case, demonstrating enhanced robustness with and without predistortion.

Figure 19.

Training and validation loss and accuracy curves for the QAM CNN–TFN equalizer. The model exhibits stable convergence and strong generalization, with validation accuracy approaching 98%.

Figure 19.

Training and validation loss and accuracy curves for the QAM CNN–TFN equalizer. The model exhibits stable convergence and strong generalization, with validation accuracy approaching 98%.

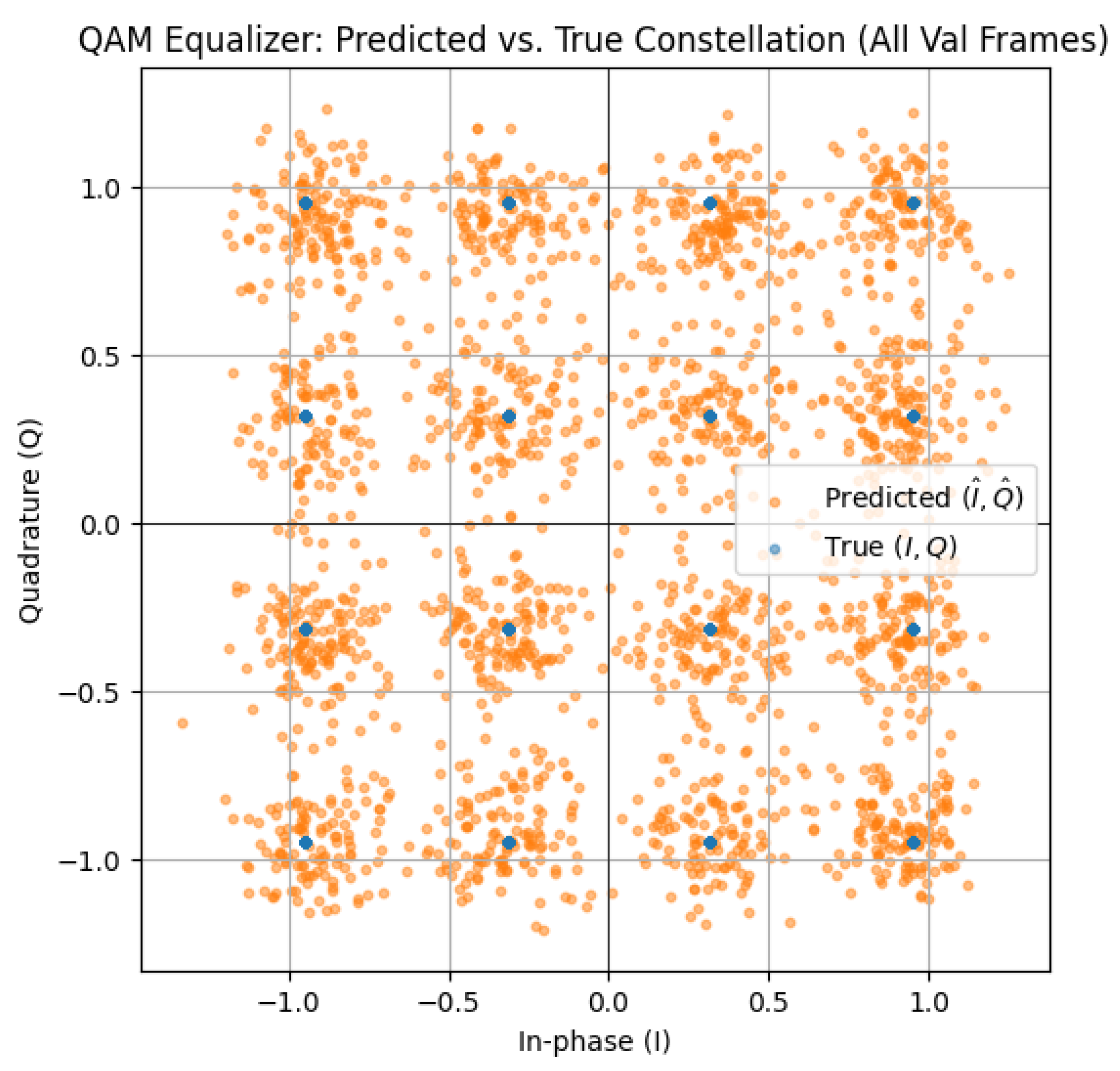

Figure 20.

Predicted vs. true 16-QAM constellation points after CNN–TFN equalization. The tight clustering around the ideal symbol positions demonstrates effective compensation of LED and channel distortions.

Figure 20.

Predicted vs. true 16-QAM constellation points after CNN–TFN equalization. The tight clustering around the ideal symbol positions demonstrates effective compensation of LED and channel distortions.

Figure 21.

Training and validation loss and accuracy curves for the PPM CNN–TFN equalizer. The model converges rapidly and achieves stable generalization, with accuracy approaching 97%.

Figure 21.

Training and validation loss and accuracy curves for the PPM CNN–TFN equalizer. The model converges rapidly and achieves stable generalization, with accuracy approaching 97%.

Figure 22.

BER performance of the PPM-based VLC system versus SNR with 95% confidence intervals. The BER decreases monotonically with increasing SNR, demonstrating improved detection reliability and near-error-free performance at high SNR.

Figure 22.

BER performance of the PPM-based VLC system versus SNR with 95% confidence intervals. The BER decreases monotonically with increasing SNR, demonstrating improved detection reliability and near-error-free performance at high SNR.

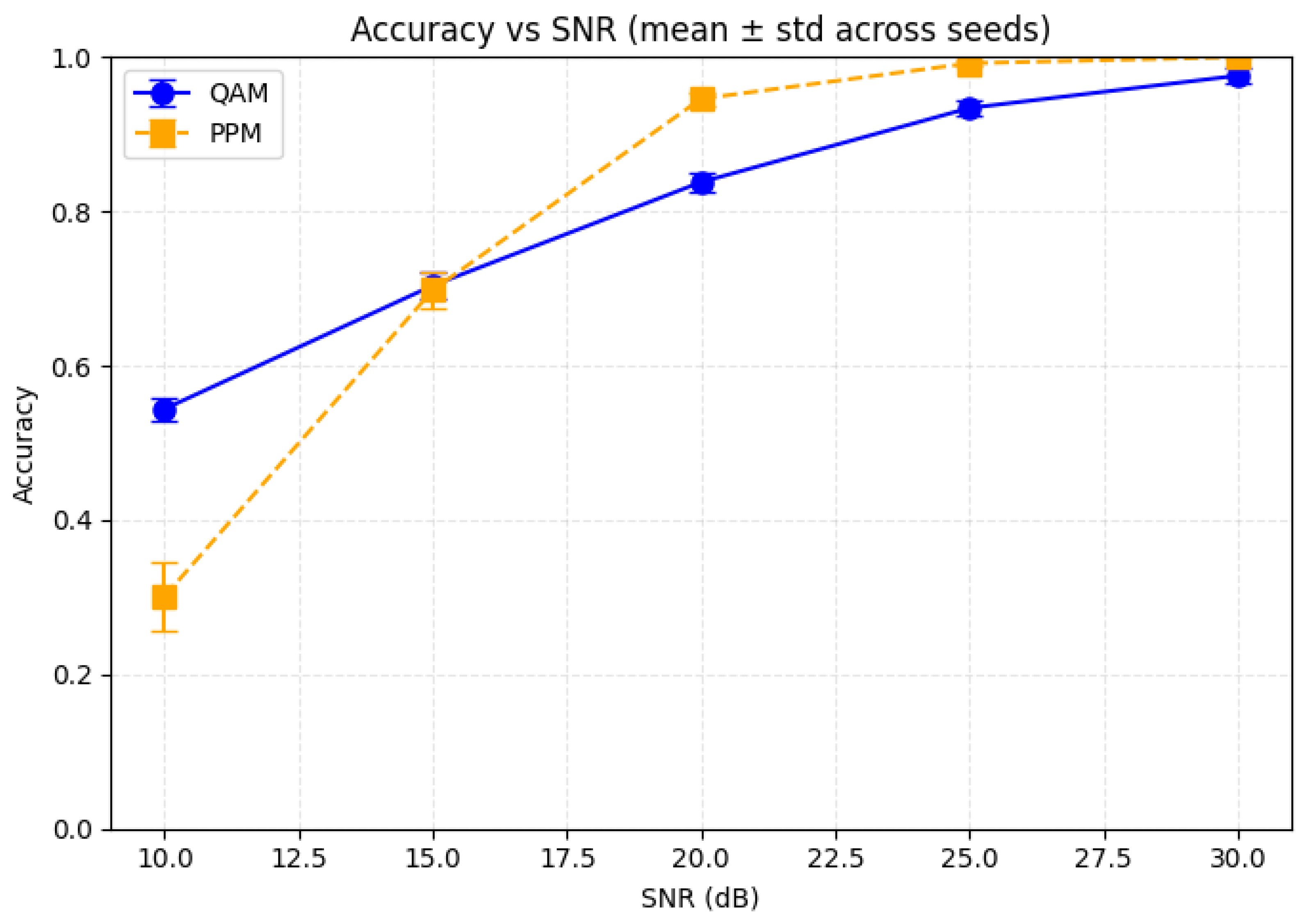

Figure 23.

Accuracy of the QAM and PPM CNN–TFN equalizers across different SNR values and random seeds. Both models show stable performance with reduced variability at higher SNRs.

Figure 23.

Accuracy of the QAM and PPM CNN–TFN equalizers across different SNR values and random seeds. Both models show stable performance with reduced variability at higher SNRs.

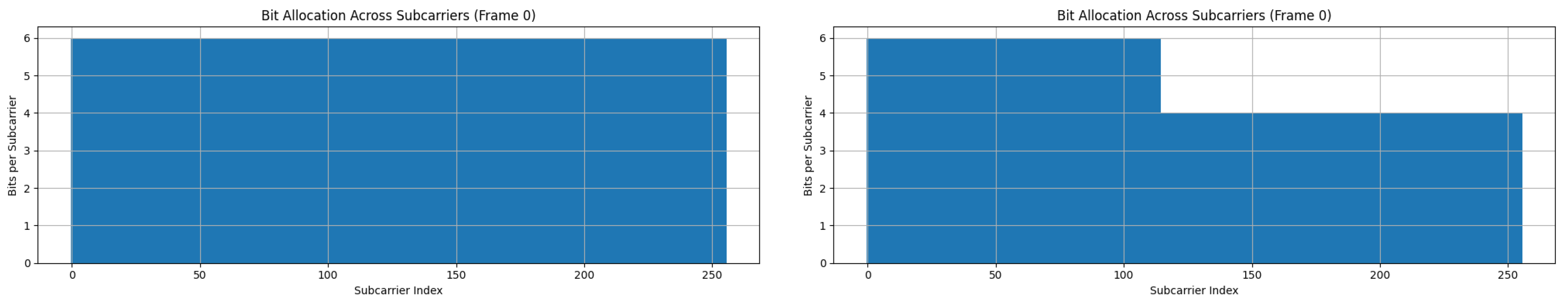

Figure 24.

Illustration of uniform bit loading (left) and adaptive bit loading (right). UBL assigns the same modulation order to all subcarriers, while ABL adapts the bit allocation according to the instantaneous SNR of each subcarrier to improve spectral efficiency.

Figure 24.

Illustration of uniform bit loading (left) and adaptive bit loading (right). UBL assigns the same modulation order to all subcarriers, while ABL adapts the bit allocation according to the instantaneous SNR of each subcarrier to improve spectral efficiency.

Figure 25.

Throughput achieved using adaptive bit loading compared with uniform bit loading. ABL increases average throughput by 16.23% by adapting the modulation order to the instantaneous SNR of each subcarrier.

Figure 25.

Throughput achieved using adaptive bit loading compared with uniform bit loading. ABL increases average throughput by 16.23% by adapting the modulation order to the instantaneous SNR of each subcarrier.

Table 1.

Optical channel gains for LOS, NLOS, and total paths.

Table 1.

Optical channel gains for LOS, NLOS, and total paths.

| Component | Gain |

|---|

| |

| |

| |

| Signal power | |

| Noise power | |

| SNR (dB) | |

Table 2.

System and channel parameters used in the VLC simulation model, including LED characteristics, receiver configuration, physical environment settings, and noise-related values.

Table 2.

System and channel parameters used in the VLC simulation model, including LED characteristics, receiver configuration, physical environment settings, and noise-related values.

| Parameter | Value | Rationale |

|---|

| Distance | 2.0 m | Represents typical indoor LOS scenarios |

| Lambertian order | 1.0 | Moderately wide LED emission pattern for realistic coverage |

| Photodetector area () | | Typical area for indoor VLC photodetector |

| Filter gain | 1.0 | Neutral filter for simplicity |

| Concentrator gain | 1.0 | Unity gain to isolate other effects |

| Reflectivity | 0.7 | Typical indoor wall/ceiling reflectivity |

| Reflector distance | [3.0 m, 4.0 m] | Models multipath reflection distance |

| Reflector angle | [45°, 60°] | Reflects common indoor surface angles |

| SNR | 30 dB | High-quality link while allowing measurable degradation |

| Noise bandwidth (B) | Hz | Represents typical photodetector bandwidth |

| Temperature (T) | 300 K | Standard room temperature |

| Load resistance () | 50 | Common in electronics for impedance matching |

| Ambient irradiance () | | Simulates low-level ambient light interference |

| Responsivity (r) | 0.7 A/W | Typical photodetector responsivity |

Table 3.

Transformer–CNN hybrid model architecture.

Table 3.

Transformer–CNN hybrid model architecture.

| Layer Type | Output Shape | Params | Remarks |

|---|

| Conv1d | (16, 64, 119) | 704 | First convolution for initial feature extraction |

| ReLU | (16, 64, 119) | 0 | Nonlinearity |

| Conv1d | (16, 128, 119) | 24,704 | Deeper feature representation |

| ReLU | (16, 128, 119) | 0 | Activation |

| Conv1d | (16, 128, 119) | 258 | Convolution with same channels |

| Dropout | (16, 128, 119) | 0 | Regularization |

| PositionalEncoding | (16, 128, 119) | 0 | Adds temporal context |

| LayerNorm | (16, 119, 128) | 256 | Normalization before attention |

| MultiheadAttention | (–1, 119, 128) → (–1, 119, 128) | 0 | Self-attention layer |

| Dropout | (16, 119, 128) | 0 | Regularization after attention |

| LayerNorm | (16, 119, 128) | 256 | Stabilizes FFN input |

| Linear | (16, 119, 256) | 33,024 | Expands dimensionality |

| ReLU | (16, 119, 256) | 0 | Nonlinearity |

| Dropout | (16, 119, 256) | 0 | Prevents overfitting |

| Linear | (16, 119, 128) | 32,896 | Compresses feature back |

| Dropout | (16, 119, 128) | 0 | Further regularization |

| TransformerEncoderBlock | (16, 119, 128) | 0 | End of 1st transformer encoder block |

| LayerNorm | (16, 119, 128) | 256 | Normalization for 2nd encoder |

| MultiheadAttention | (–1, 119, 128) → (–1, 119, 128) | 0 | Self-attention layer |

| Dropout | (16, 119, 128) | 0 | Regularization |

| LayerNorm | (16, 119, 128) | 256 | Normalization |

| Linear | (16, 119, 256) | 33,024 | FFN expansion |

| ReLU | (16, 119, 256) | 0 | Nonlinearity |

| Dropout | (16, 119, 256) | 0 | Prevents overfitting |

| Linear | (16, 119, 128) | 32,896 | Reduces dimensionality |

| Dropout | (16, 119, 128) | 0 | Dropout |

| TransformerEncoderBlock | (16, 119, 128) | 0 | End of 2nd transformer encoder block |

| Linear | (16, 119, 2) | 258 | Maps to symbol space |

| Linear | (16, 119, 2) | 6 | Final projection for output |

Table 4.

Model architecture summary for PPM classifier.

Table 4.

Model architecture summary for PPM classifier.

| Layer (Type) | Output Shape | Params | Remarks |

|---|

| Conv1D-1 | [16, 64, 128] | 384 | Initial convolution for local temporal feature extraction. |

| ReLU-2 | [16, 64, 128] | 0 | Nonlinear activation improving feature separability. |

| PositionalEncoding-3 | [16, 128, 64] | 0 | Adds temporal-order information via sinusoidal encoding. |

| MultiHeadAttention-4 | [16, 128, 64] | 0 | Captures long-range temporal dependencies. |

| Dropout-5 | [16, 128, 64] | 0 | Regularization to reduce overfitting. |

| LayerNorm-6 | [16, 128, 64] | 128 | Normalizes activations before FFN for stability. |

| Linear-7 | [16, 128, 128] | 8320 | FFN expansion increasing representation capacity. |

| ReLU-8 | [16, 128, 128] | 0 | Nonlinearity inside the feed-forward network. |

| Linear-9 | [16, 128, 64] | 8256 | FFN compression projecting features back to 64 dims. |

| Dropout-10 | [16, 128, 64] | 0 | Regularization after FFN to prevent overfitting. |

| LayerNorm-11 | [16, 128, 64] | 128 | Layer normalization before the next encoder block. |

| TransformerEncoderBlock-12 | [16, 128, 64] | 0 | Second encoder block refining temporal representations. |

| GlobalAvgPool-13 | [16, 64] | 0 | Pools temporal features into a global embedding. |

| Linear-14 (Output) | [16, 128] | 8320 | Final classifier projecting features to PPM symbol logits. |

Table 5.

BER and MSE comparison for QAM and PPM signals with and without PD. Case and 3rd-order PD.

Table 5.

BER and MSE comparison for QAM and PPM signals with and without PD. Case and 3rd-order PD.

| Scenario | | | | |

|---|

| Without PD | 0.0962 | 0 | 2.269 | 2.811 |

| With PD | 0.0800 | 0 | 1.909 | 2.811 |

Table 6.

BER and MSE comparison for QAM and PPM signals with 5th-order PD and , showing improvements due to predistortion.

Table 6.

BER and MSE comparison for QAM and PPM signals with 5th-order PD and , showing improvements due to predistortion.

| Scenario | | | | |

|---|

| Without PD | 0.0629 | <0.00602 | 1.395 | 2.811 |

| With PD | 0.0456 | <0.00602 | 1.051 | 2.811 |

Table 7.

BER and MSE comparison for 7th-order PD and . Higher-order PD improves performance for both QAM and PPM.

Table 7.

BER and MSE comparison for 7th-order PD and . Higher-order PD improves performance for both QAM and PPM.

| Scenario | | | | |

|---|

| Without PD | 0.0625 | 0.4230 | 0.1306 | 1.806 |

| With PD | 0.0472 | 0.3406 | 0.1350 | 1.806 |

Table 8.

BER and MSE performance of the hybrid VLC system using the conventional polynomial predistorter (simple PD).

Table 8.

BER and MSE performance of the hybrid VLC system using the conventional polynomial predistorter (simple PD).

| Scenario | | | | |

|---|

| With Simple PD | 0.0483 | 0.3516 | 1.138 | 1.806 |

Table 9.

Evolution of BER and MSE for QAM and PPM across training epochs of the CNN-based predistorter. Results show the convergence behavior and the modest performance gains achieved by the neural PD.

Table 9.

Evolution of BER and MSE for QAM and PPM across training epochs of the CNN-based predistorter. Results show the convergence behavior and the modest performance gains achieved by the neural PD.

| Epoch | | | | |

|---|

| 10 | 0.0524 | 0.3417 | 1.163 | 1.806 |

| 20 | 0.0495 | 0.3406 | 1.163 | 1.806 |

| 30 | 0.0489 | 0.3406 | 1.160 | 1.806 |

| 40 | 0.0508 | 0.3406 | 1.155 | 1.806 |

| 50 | 0.0502 | 0.3406 | 1.152 | 1.806 |

| 60 | 0.0487 | 0.3510 | 1.135 | 1.806 |

| 70 | 0.0483 | 0.3570 | 1.132 | 1.806 |

| 80 | 0.0480 | 0.3510 | 1.133 | 1.806 |

| 90 | 0.0493 | 0.3400 | 1.157 | 1.806 |

| 100 | 0.0475 | 0.3500 | 1.137 | 1.806 |

Table 10.

BER and MSE values for QAM and PPM under different PD orders at . The results show that increasing the PD order significantly improves QAM accuracy, while PPM exhibits only minor changes due to its robustness to amplitude distortion.

Table 10.

BER and MSE values for QAM and PPM under different PD orders at . The results show that increasing the PD order significantly improves QAM accuracy, while PPM exhibits only minor changes due to its robustness to amplitude distortion.

| PD Order | | | | |

|---|

| 1st | 0.0643 | 0.357 | 1.4520 | 1.806 |

| 3rd | 0.0524 | 0.357 | 1.2030 | 1.806 |

| 5th | 0.0483 | 0.352 | 1.2380 | 1.806 |

| 7th | 0.0472 | 0.345 | 1.1200 | 1.806 |

Table 11.

BER and MSE comparison for the QAM branch under a pilot spacing of 8. Pilot-assisted equalization greatly improves accuracy but introduces notable overhead, reducing spectral efficiency.

Table 11.

BER and MSE comparison for the QAM branch under a pilot spacing of 8. Pilot-assisted equalization greatly improves accuracy but introduces notable overhead, reducing spectral efficiency.

| Method | | |

|---|

| NoEQ (no PD) | 0.267 | 9.954 |

| PilotEQ (no PD) | 0.067 | 1.492 |

| NoEQ (with PD) | 0.262 | 9.956 |

| PilotEQ (with PD) | 0.048 | 1.133 |

Table 12.

BER and MSE comparison for the QAM branch under a pilot spacing of 16. Results show that moderate pilot density maintains effective equalization with less overhead than dense pilot insertion.

Table 12.

BER and MSE comparison for the QAM branch under a pilot spacing of 16. Results show that moderate pilot density maintains effective equalization with less overhead than dense pilot insertion.

| Method | | |

|---|

| NoEQ (no PD) | 0.2606 | 9.9431 |

| PilotEQ (no PD) | 0.0406 | 0.871 |

| NoEQ (with PD) | 0.256 | 9.943 |

| PilotEQ (with PD) | 0.0266 | 0.667 |

Table 13.

BER and MSE comparison for the QAM branch under a pilot spacing of 24. Sparse pilot insertion improves throughput while maintaining accurate equalization and low BER.

Table 13.

BER and MSE comparison for the QAM branch under a pilot spacing of 24. Sparse pilot insertion improves throughput while maintaining accurate equalization and low BER.

| Method | | |

|---|

| NoEQ (no PD) | 0.2606 | 10.0143 |

| PilotEQ (no PD) | 0.037 | 0.931 |

| NoEQ (with PD) | 0.257 | 10.0143 |

| PilotEQ (with PD) | 0.0248 | 0.667 |

Table 14.

Summary of QAM BER and MSE for pilot spacings of 8, 16, 24, and 25 subcarriers. The optimal performance–efficiency balance is obtained at a spacing of 24, while larger spacings (e.g., 25) begin to introduce interpolation errors.

Table 14.

Summary of QAM BER and MSE for pilot spacings of 8, 16, 24, and 25 subcarriers. The optimal performance–efficiency balance is obtained at a spacing of 24, while larger spacings (e.g., 25) begin to introduce interpolation errors.

| Pilot Spacing | BERQAM | MSEQAM |

|---|

| 8 | 0.048 | 1.13 |

| 16 | 0.0266 | 0.667 |

| 24 | 0.0248 | 0.693 |

| 25 | 0.0264 | 0.693 |

Table 15.

BER and MSE of the PPM branch with and without PD under strong LED nonlinearity (). PD improves pulse-detection accuracy, reducing BER, while MSE remains unchanged due to the amplitude-insensitive nature of PPM.

Table 15.

BER and MSE of the PPM branch with and without PD under strong LED nonlinearity (). PD improves pulse-detection accuracy, reducing BER, while MSE remains unchanged due to the amplitude-insensitive nature of PPM.

| Method | BERPPM | MSEPPM |

|---|

| Without PD | 0.4231 | 1.8064 |

| With PD | 0.3516 | 1.8064 |

Table 16.

Ablation study evaluating the contributions of key system components under identical channel and SNR conditions.

Table 16.

Ablation study evaluating the contributions of key system components under identical channel and SNR conditions.

| Configuration | PD | CNN | Transformer | ABL | BERQAM | Throughput Gain |

|---|

| Baseline (no AI, no PD) | × | × | × | × | High | – |

| PD only | ✓ | × | × | × | ↓ | – |

| CNN equalizer (no TFN) | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | ↓↓ | – |

| CNN–TFN equalizer | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | ↓↓↓ | – |

| CNN–TFN + ABL (full system) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Lowest | +16% |

Table 17.

Accuracy of the QAM and PPM CNN–TFN equalizers across different SNR values and random seeds. Results show consistent performance trends and reduced variability at higher SNR.

Table 17.

Accuracy of the QAM and PPM CNN–TFN equalizers across different SNR values and random seeds. Results show consistent performance trends and reduced variability at higher SNR.

| Case | Modulation | 10 dB | 15 dB | 20 dB | 25 dB | 30 dB |

|---|

| 1 | QAM | 0.55 | 0.72 | 0.85 | 0.94 | 0.98 |

| 2 | QAM | 0.54 | 0.70 | 0.84 | 0.94 | 0.98 |

| 3 | QAM | 0.55 | 0.70 | 0.83 | 0.93 | 0.98 |

| 4 | QAM | 0.52 | 0.68 | 0.82 | 0.92 | 0.96 |

| 5 | QAM | 0.56 | 0.72 | 0.85 | 0.94 | 0.98 |

| 1 | PPM | 0.275 | 0.68 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 1.00 |

| 2 | PPM | 0.27 | 0.70 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 1.00 |

| 3 | PPM | 0.37 | 0.71 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 1.00 |

| 4 | PPM | 0.32 | 0.73 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 1.00 |

| 5 | PPM | 0.27 | 0.67 | 0.94 | 1.00 | 1.00 |