AGL-UNet: Adaptive Global–Local Modulated U-Net for Multitask Sea Ice Mapping

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A multi-task automated sea ice mapping network is developed to meet practical requirements for simultaneously estimating multiple sea ice parameters, substantially improving operational efficiency.

- (2)

- The ARC block and the GLCM block are introduced to better utilize correlations among multi source inputs and feature associations across different sea ice types, thereby improving the accuracy of sea ice parameter retrieval.

- (3)

- An adaptive loss weighting strategy is proposed, which adjusts task weights based on the gradient norms of shared parameters with respect to each task loss, ensuring more balanced multi-task training.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset and Preprocessing

2.2. Methods

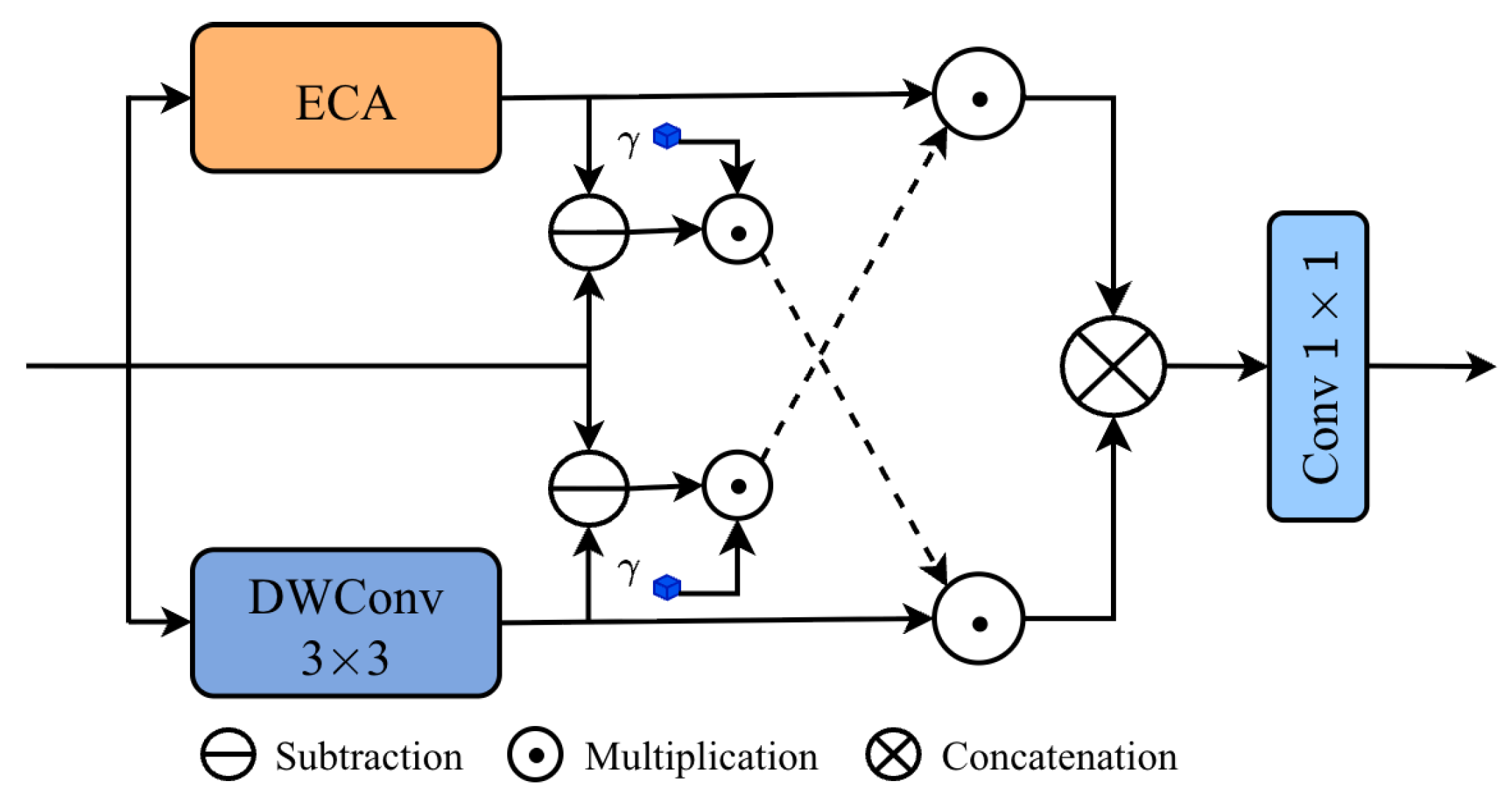

2.2.1. ARC Block

2.2.2. GLCM Block

2.2.3. U-Net Decoder

2.2.4. Adaptive Loss Weighting Method

3. Experiments

3.1. Experimental Details

3.2. Evaluation Metrics

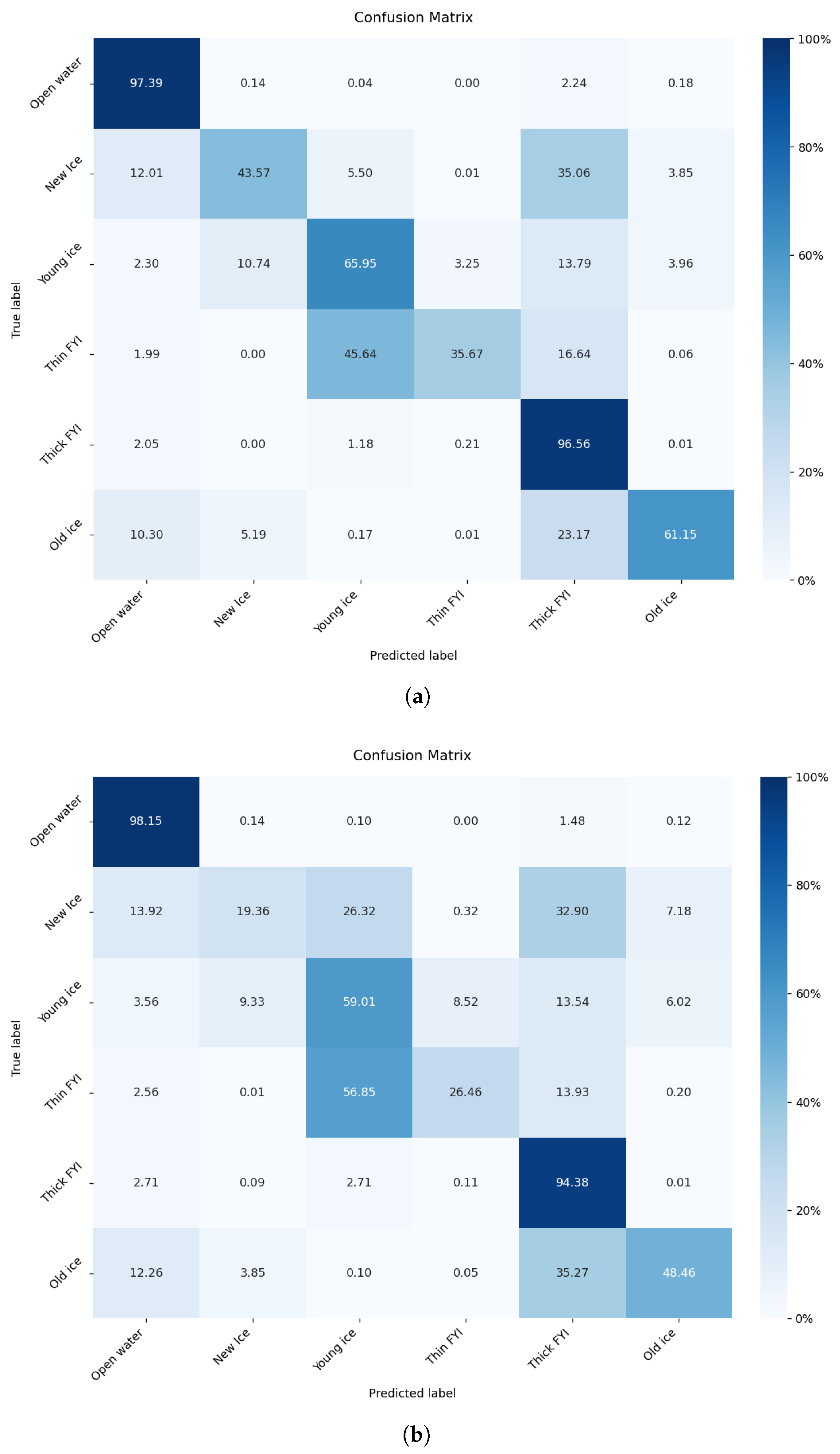

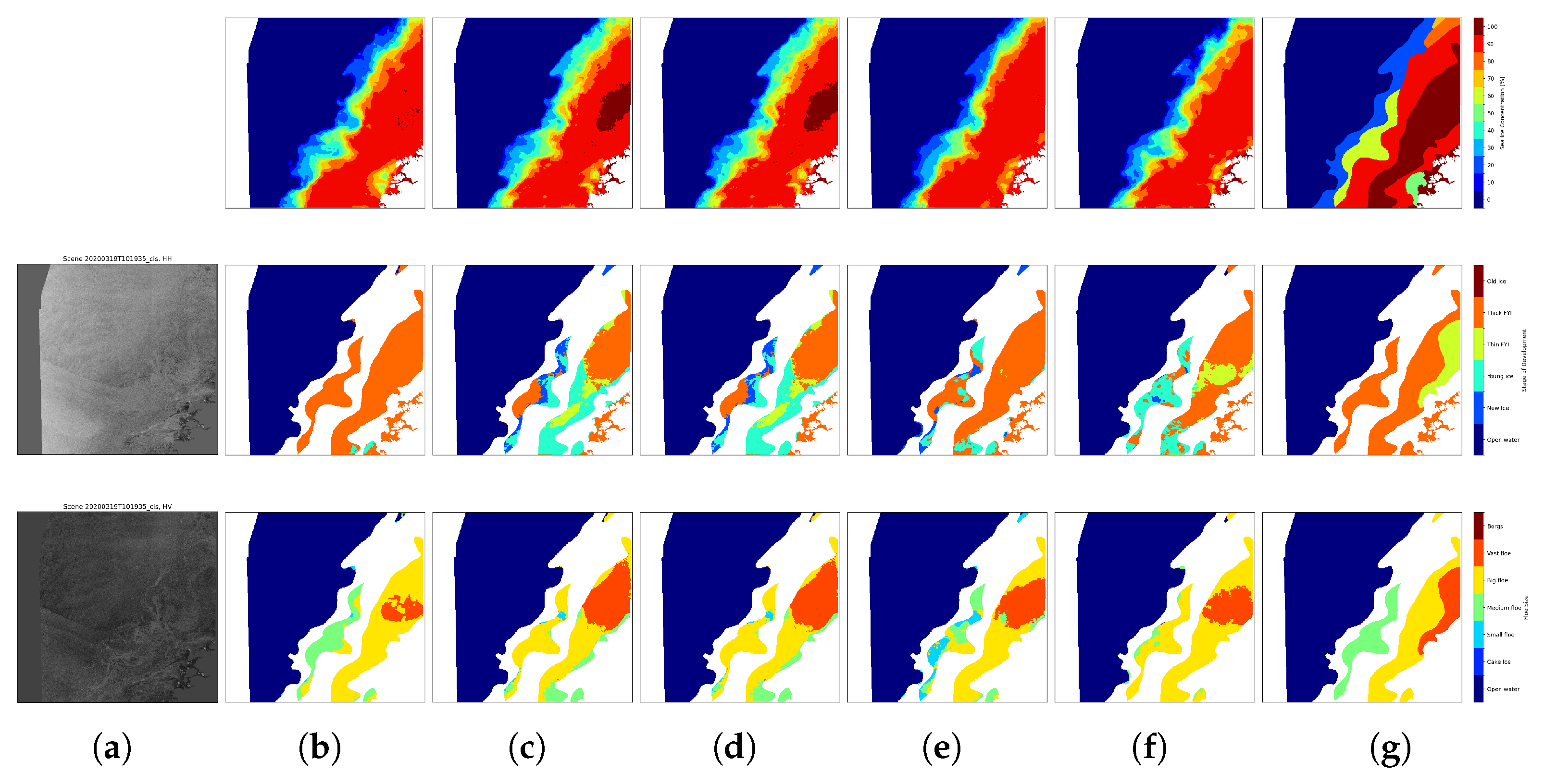

3.3. Experimental Results

3.4. Ablation Experiments

3.5. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vihma, T. Effects of Arctic sea ice decline on weather and climate: A review. Surv. Geophys. 2014, 35, 1175–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, P.M.; Hughes, N.; Bourbonnais, P.; Stroeve, J.; Rabenstein, L.; Bhatt, U.; Little, J.; Wiggins, H.; Fleming, A. Sea-ice information and forecast needs for industry maritime stakeholders. Polar Geogr. 2020, 43, 160–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serreze, M.C.; Francis, J.A. The Arctic amplification debate. Clim. Change 2006, 76, 241–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.R.; Roushdi, M.; Aboelkhear, M. Potential benefits of climate change on navigation in the northern sea route by 2050. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Wang, C.; Li, J.; Sui, Y. DF-UHRNet: A modified CNN-based deep learning method for automatic sea ice classification from Sentinel-1A/B SAR images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, M.D.; Lannuzel, D.; Else, B.; Angot, H.; Campbell, K.; Crabeck, O.; Delille, B.; Hayashida, H.; Lizotte, M.; Loose, B.; et al. Polar oceans and sea ice in a changing climate. Elem. Sci. Anth. 2023, 11, 00056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Hsu, C.Y.; Tedesco, M. Advancing Arctic Sea Ice Remote Sensing with AI and Deep Learning: Opportunities and Challenges. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gelis, I.; Colin, A.; Longépé, N. Prediction of categorized sea ice concentration from Sentinel-1 SAR images based on a fully convolutional network. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 5831–5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamber, M.S.; Scott, K.A.; Pedersen, L.T. Accounting for label errors when training a convolutional neural network to estimate sea ice concentration using operational ice charts. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 1502–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, C.L.; Scott, K.A. Estimating sea ice concentration from SAR: Training convolutional neural networks with passive microwave data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 4735–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Patel, M.; Xu, L.; Chen, Y.; Scott, K.A.; Clausi, D.A. A Weakly Supervised Learning Approach for Sea Ice Stage of Development Classification From AI4Arctic Sea Ice Challenge Dataset. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhong, W.; Jin, C.; Liu, B.; Li, F. A Spatio-Temporal Deep Learning Model for Automatic Arctic Sea Ice Classification with Sentinel-1 SAR Imagery. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Gao, W.; He, Q.; Liotta, A.; Guo, W. Si-stsar-7: A large sar images dataset with spatial and temporal information for classification of winter sea ice in hudson bay. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagi, A.S.; Kumar, D.; Sola, D.; Scott, K.A. RUF: Effective sea ice floe segmentation using end-to-end RES-UNET-CRF with dual loss. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Shokr, M.; Li, X.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Hui, F.; Cheng, X. MYI floes identification based on the texture and shape feature from dual-polarized Sentinel-1 imagery. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Cai, J.; Ding, S. The identification of ice floes and calculation of sea ice concentration based on a deep learning method. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokholm, A.; Buus-Hinkler, J.; Wulf, T.; Korosov, A.; Saldo, R.; Pedersen, L.T.; Arthurs, D.; Dragan, I.; Modica, I.; Pedro, J.; et al. The AutoICE Challenge. Cryosphere 2024, 18, 3471–3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buus-Hinkler, J.; Wulf, T.; Stokholm, A.; Korosov, A.; Saldo, R.; Pedersen, L.T.; Arthurs, D.; Solberg, R.; Longépé, N.; Kreiner, M.B. AI4Arctic Sea Ice Challenge Dataset. Dataset, Danish Meteorological Institute. 2022. Available online: https://www.eotdl.com/datasets/ai4arctic-sea-ice-challenge-ready-to-train (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Chen, X.; Patel, M.; Cantu, F.J.P.; Park, J.; Turnes, J.N.; Xu, L.; Scott, K.A.; Clausi, D.A. MMSeaIce: A collection of techniques for improving sea ice mapping with a multi-task model. Cryosphere 2024, 18, 1621–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cantu, F.J.P.; Patel, M.; Xu, L.; Brubacher, N.C.; Scott, K.A.; Clausi, D.A. A comparative study of data input selection for deep learning-based automated sea ice mapping. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 131, 103920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.06521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrycks, D. Gaussian Error Linear Units (Gelus). arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.08415. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, B.; Zhu, P.; Li, P.; Zuo, W.; Hu, Q. ECA-Net: Efficient Channel Attention for Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1910.03151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Su, J. Multitasking Learning Ramblings (I): In the Name of Loss. 2022. Available online: https://spaces.ac.cn/archives/8870 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Sgdr: Stochastic gradient descent with warm restarts. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1608.03983. [Google Scholar]

- Jalayer, S.; Taleghan, S.A.; Lima, R.P.d.; Vahedi, B.; Hughes, N.; Banaei-Kashani, F.; Karimzadeh, M. Enhancing and Interpreting Deep Learning for Sea Ice Charting using the AutoICE Benchmark. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2025, 38, 101538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, P.; Liu, X.; An, L. A Dual-Branch Architecture for Adaptive Loss Multitask Mapping Based on AI4Arctic Sea Ice Challenge Dataset. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2025, 22, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Obervation Group | Variable Description | Number of Channels |

|---|---|---|

| SAR | HH, HV, incidence angle | 3 |

| AMSR2 | Dual-polarized AMSR2 brightness temperature data in 18.7 and 36.5 GHz | 4 |

| ERA5 | 10-m wind speed, 2-m air temperature, total column water vapor, total column cloud liquid water | 5 |

| Location, time | Latitude/longitude of each pixel, distance map and scene acquisition month | 4 |

| Optimizer | Stochastic Gradient Descent with Momentum (SGDM) |

|---|---|

| Learning rate | |

| Weight decay | |

| Scheduler | Cosine annealing with warm restarts |

| Batch size | 16 |

| Number of iterations per epoch | 500 |

| Total epoch | 200 |

| Number of epochs for the first restart | 20 |

| Downscaling ratio | 10 |

| Data augmentation | Rotation, flip, random scale, CutMix |

| Patch size | 256 |

| ARC Block Lengths | |

| ARC Block Kernel Size | |

| Loss functions | Mean square error loss for SIC, cross entropy loss for SOD and FLOE |

| Sea Ice Parameter | Metric (%) | Weight in Combined Score |

|---|---|---|

| SIC | ||

| SOD | ||

| FLOE |

| Method | SIC (%) | SOD (%) | FLOE (%) | Combined Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [19] | ||||

| [27] | ||||

| [28] | ||||

| AGL-UNet |

| Model Number | Modifications Compared to Model 1 | SIC (%) | SOD (%) | FLOE (%) | Combined Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N/A (full model) | ||||

| 2 | Remove ARC block | ||||

| 3 | Remove GLCM block | ||||

| 4 | Remove CBAM block | ||||

| 5 | Remove adaptive loss weighting method |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, D.; Zheng, F. AGL-UNet: Adaptive Global–Local Modulated U-Net for Multitask Sea Ice Mapping. Sensors 2026, 26, 959. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030959

Chen D, Zheng F. AGL-UNet: Adaptive Global–Local Modulated U-Net for Multitask Sea Ice Mapping. Sensors. 2026; 26(3):959. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030959

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Deyang, and Fuqiang Zheng. 2026. "AGL-UNet: Adaptive Global–Local Modulated U-Net for Multitask Sea Ice Mapping" Sensors 26, no. 3: 959. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030959

APA StyleChen, D., & Zheng, F. (2026). AGL-UNet: Adaptive Global–Local Modulated U-Net for Multitask Sea Ice Mapping. Sensors, 26(3), 959. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030959