2.1. Dataset

The dataset utilized in this algorithm comprises public medical data obtained from the Helsinki University Hospital [

12]. This dataset comprises multi-channel electroencephalograms from 79 term neonates admitted to the NICU at Helsinki University Hospital. The study involving this dataset has received the necessary ethical approvals. The EEG signals were acquired using the NicoletOne vEEG System (Natus Medical, Middleton, WI, USA) at a sampling frequency of 256 Hz, with a recording duration of approximately 60 min per subject. Specifically, the duration of each window was set to 2 s. Although the raw EEG signals were sampled at 256 Hz, we downsampled them to 128 Hz during preprocessing to reduce computational complexity and filter out high-frequency artifacts. Consequently, each 2-s window corresponds to 256 sampling points in the time domain.

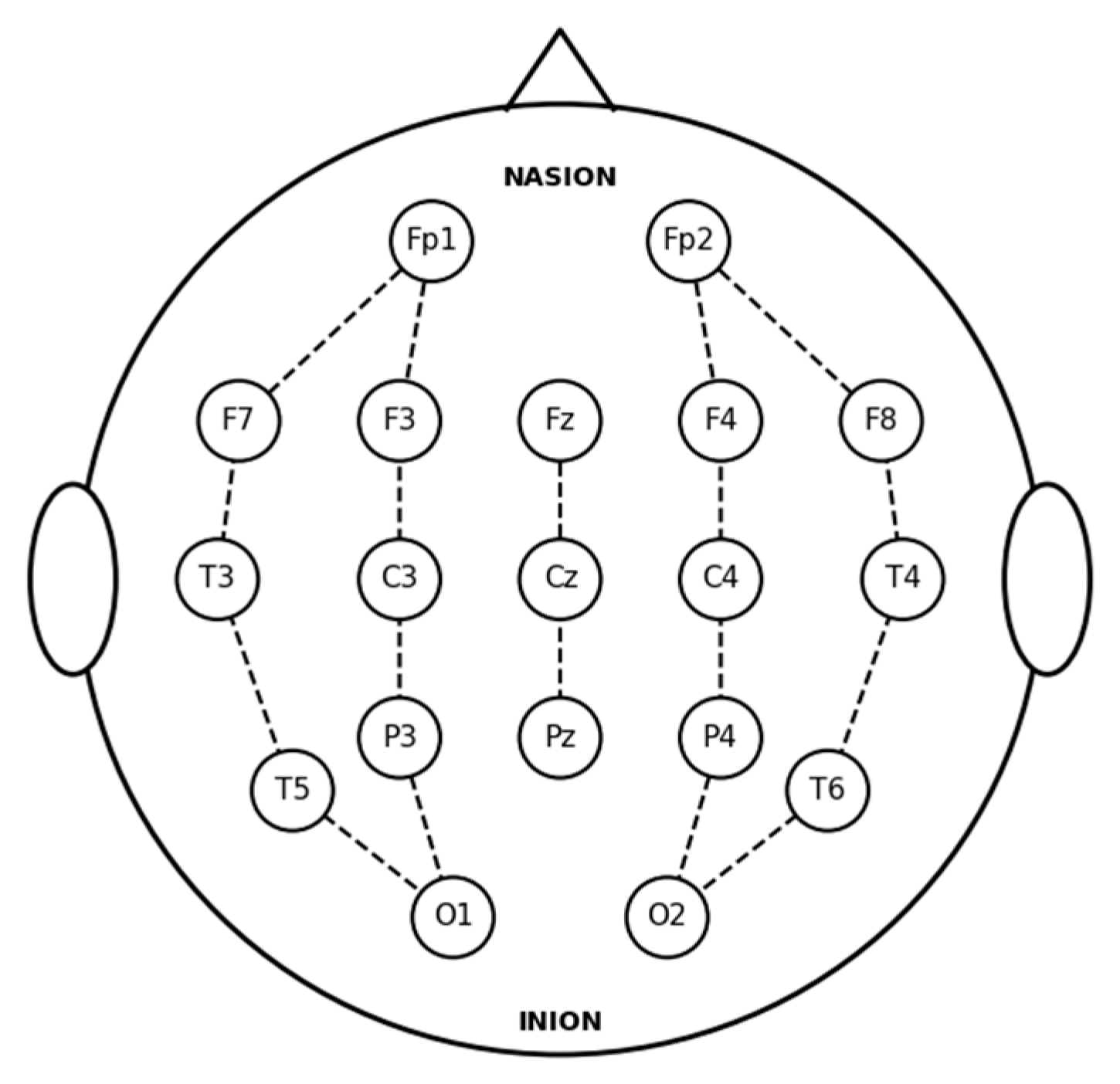

Each recording file contains potential data from 19 electrodes, all positioned and labeled in accordance with the international 10–20 system.

Figure 1 illustrates the standard 10–20 electrode layout utilized for the EEG recordings. The 18 bipolar channels derived from these electrodes are defined as follows: Fp2-F4, F4-C4, C4-P4, P4-O2, Fp1-F3, F3-C3, C3-P3, P3-O1, Fp2-F8, F8-T4, T4-T6, T6-O2, Fp1-F7, F7-T3, T3-T5, T5-O1, Fz-Cz, and Cz-Pz.

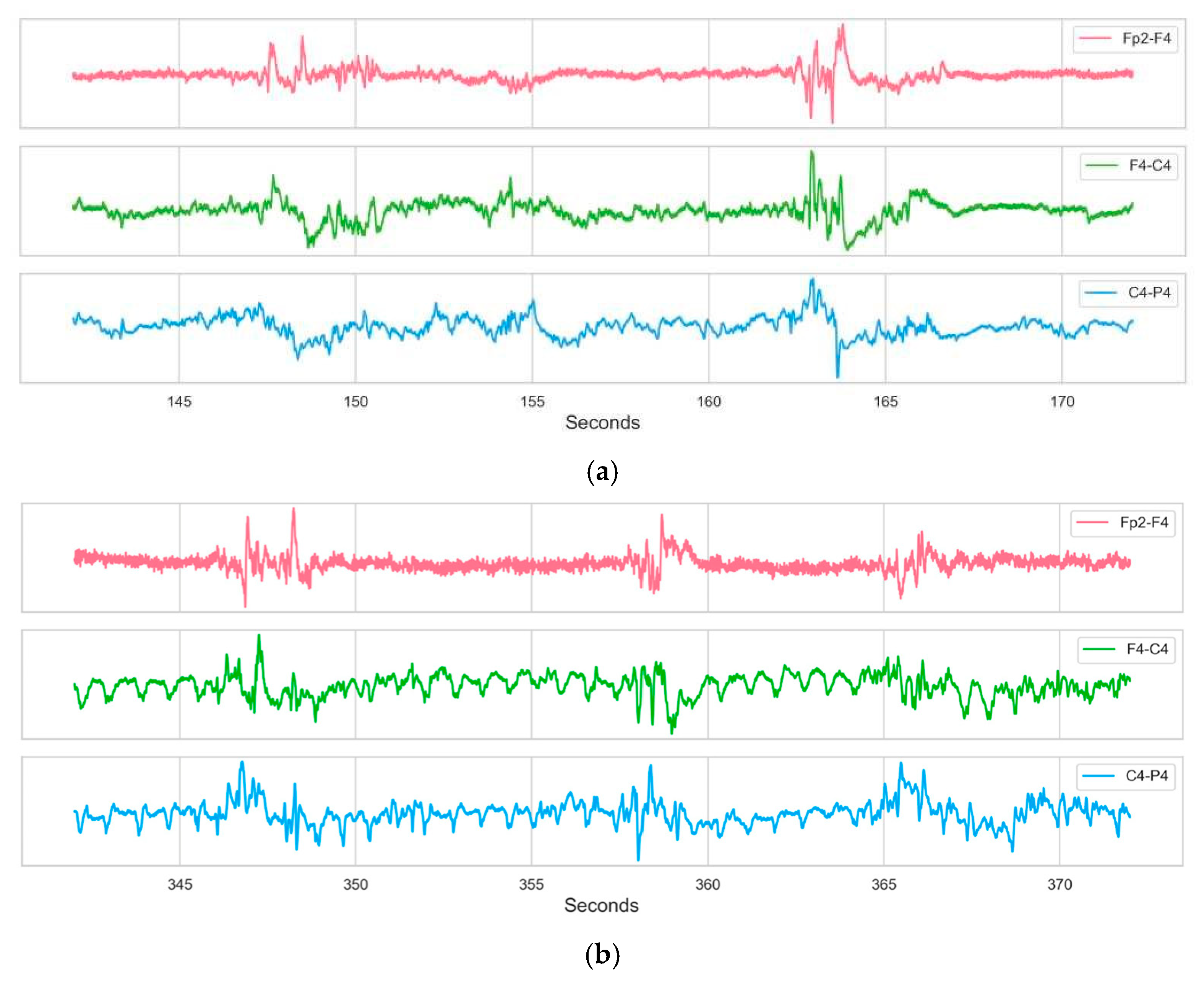

Figure 2 displays the EEG activity from Subject 9, highlighting specific segments corresponding to non-seizure and seizure periods.

2.2. Data Preprocessing

The dataset was annotated on a second-by-second basis (1 s temporal resolution) by three independent clinical experts. A label value of 0 indicates that the expert did not observe a seizure during that second, whereas a label value of 1 indicates that the expert observed a seizure. Given the discrepancies in seizure identification among experts, this study established a Majority Voting Protocol applied to the raw annotations provided by the three independent clinical experts to construct robust supervisory signals. According to this protocol, for any given 1 s time window, a segment is confirmed as a seizure sample if at least two experts simultaneously classify it as abnormal (label 1); otherwise, the segment is uniformly rectified as a non-seizure sample (label 0). Consequently, the following definitions are provided: Let

denote the index of the sliding window (

). To ensure label consistency, the ground truth label

for the

-th window is determined by the expert consensus at the window’s central time point. The label generation rule is formalized as follows:

where

represents the annotation of the

-th expert at the central second of the window (1 for seizure, 0 for normal).

Specifically, a sample is designated as positive only if a minimum of two experts concur on the seizure classification; otherwise, it is labeled as negative. To quantify label uncertainty and minimize the impact of label noise on model training, this study introduces the Annotation Disagreement Rate (ADR) as a metric for sample quality assessment. For a given subject, the ADR is defined as the ratio of the total duration of disagreement to the total duration of the raw recording:

where

represents the cumulative duration (in seconds) of all epochs where the expert consensus was not unanimous (i.e.,

). Based on this metric, a rigorous data selection strategy was implemented. To construct a class-balanced and high-quality experimental subset, 15 subjects exhibiting the highest annotation consistency were selected from the “Seizure Group” and the “Non-Seizure Group”, respectively, by ranking them in ascending order of ADR. This resulted in a total cohort of 30 subjects. This strategy effectively eliminated marginal samples with ambiguous labels, ensuring that the model was trained on data characterized by high clinical consensus. This selection strategy prioritizes label certainty. By filtering out subjects with high inter-rater disagreement (high ADR), we aim to minimize the impact of label noise on model training, ensuring the model learns from high-confidence consensus labels rather than ambiguous annotations. It is important to note that this selection criterion filters for label certainty rather than biological homogeneity. The selected subjects retain significant physiological heterogeneity in terms of gestational age and seizure morphology, ensuring that the model learns robust pathological features applicable to diverse populations rather than overfitting to ambiguous annotations.

The original dataset inherently categorizes subjects based on clinical annotations. Specifically, the 39 infants identified as having experienced at least one seizure event constituted the candidate ‘Seizure Group’, whereas the 22 infants unanimously classified as seizure-free formed the ‘Non-Seizure Group’.

Table 1 presents the annotation data for representative infant EEG samples.

Given that data exhibiting significant inter-expert disagreement may compromise model performance, we selected subjects 9, 11, 13, 21, 31, 34, 36, 44, 47, 50, 52, 62, 66, 68, and 75 from the group identified as having seizures, as these subjects demonstrated minimal discrepancies in expert annotation. Concurrently, subjects 3, 10, 18, 27, 28, 29, 30, 32, 35, 37, 45, 48, 49, 53, and 55 were selected from the seizure-free group to jointly constitute the final dataset. This strategy not only enriches the diversity of the dataset but also enhances the generalization performance of the model.

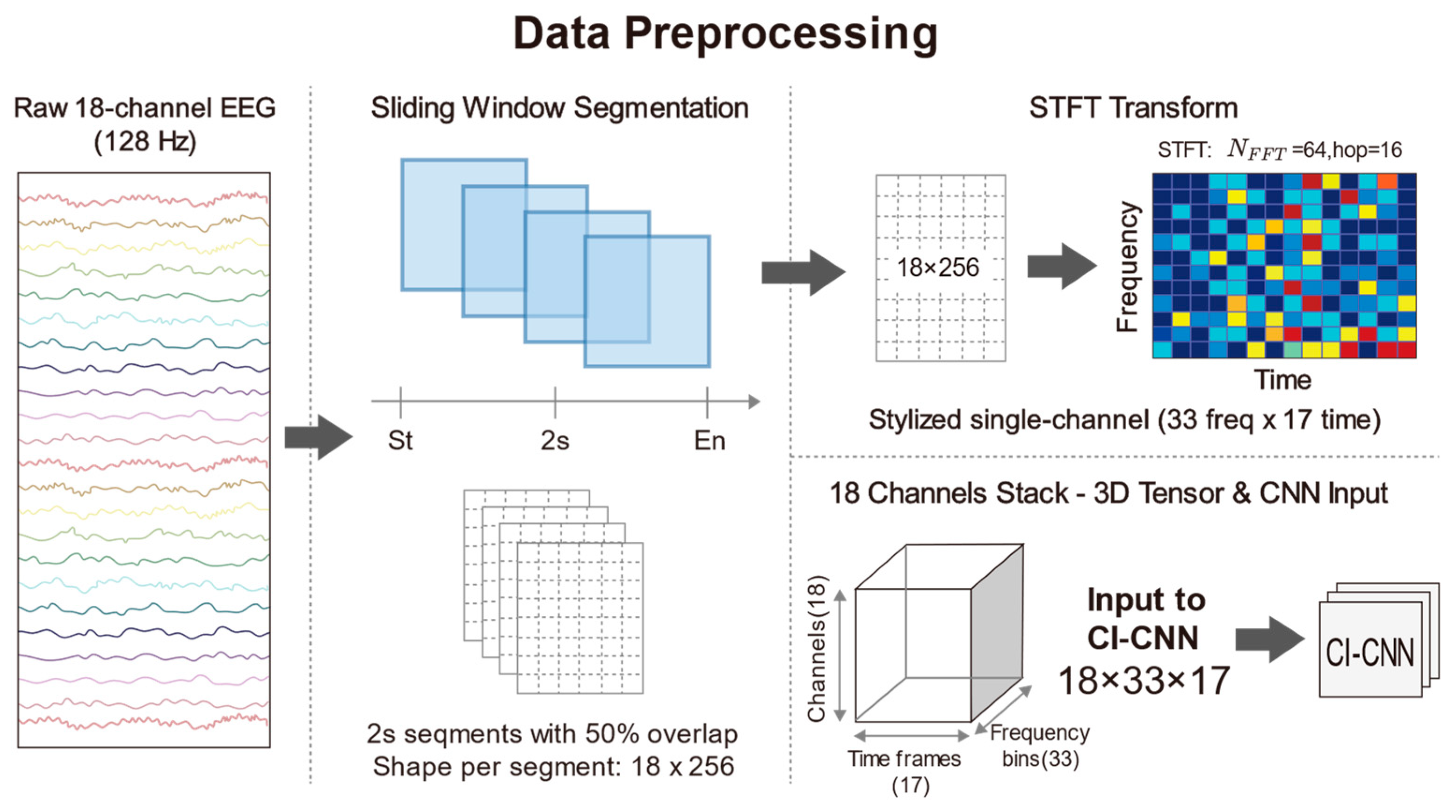

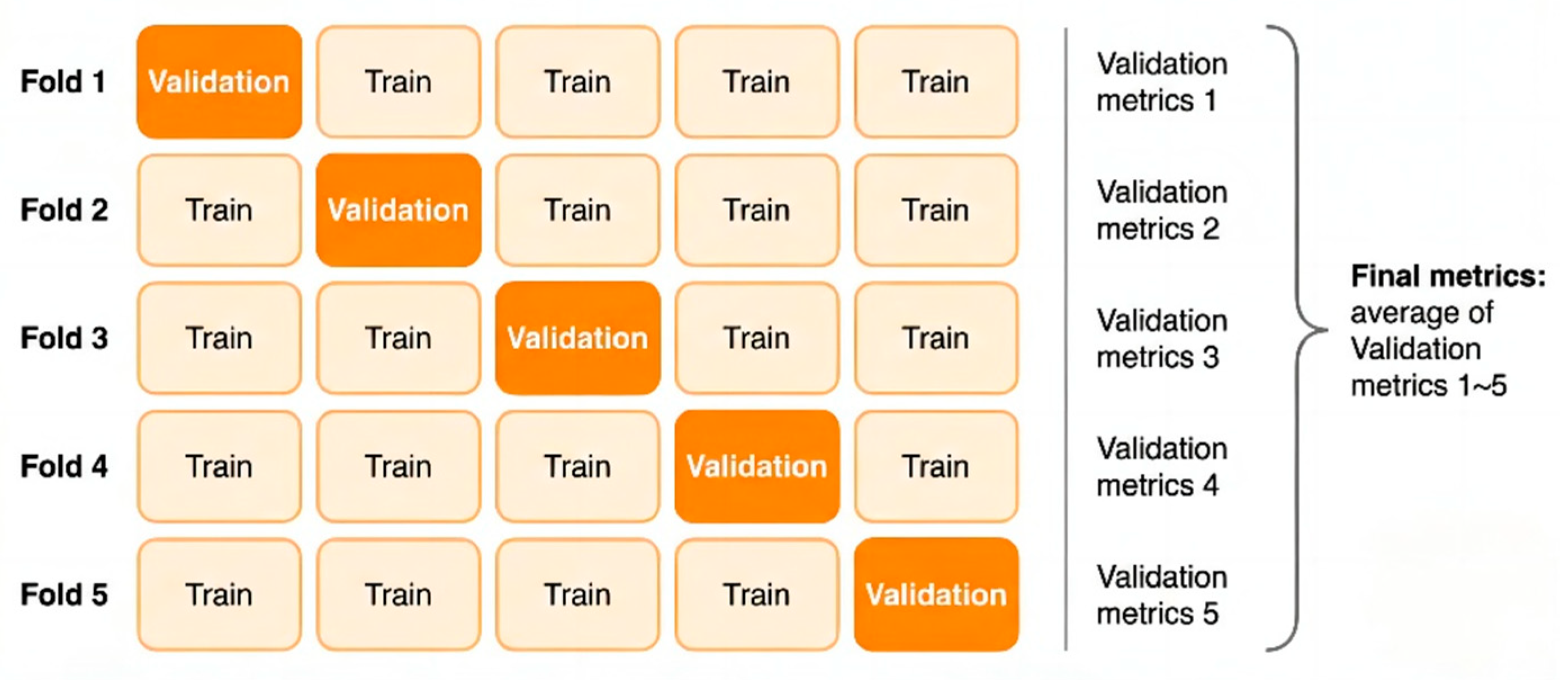

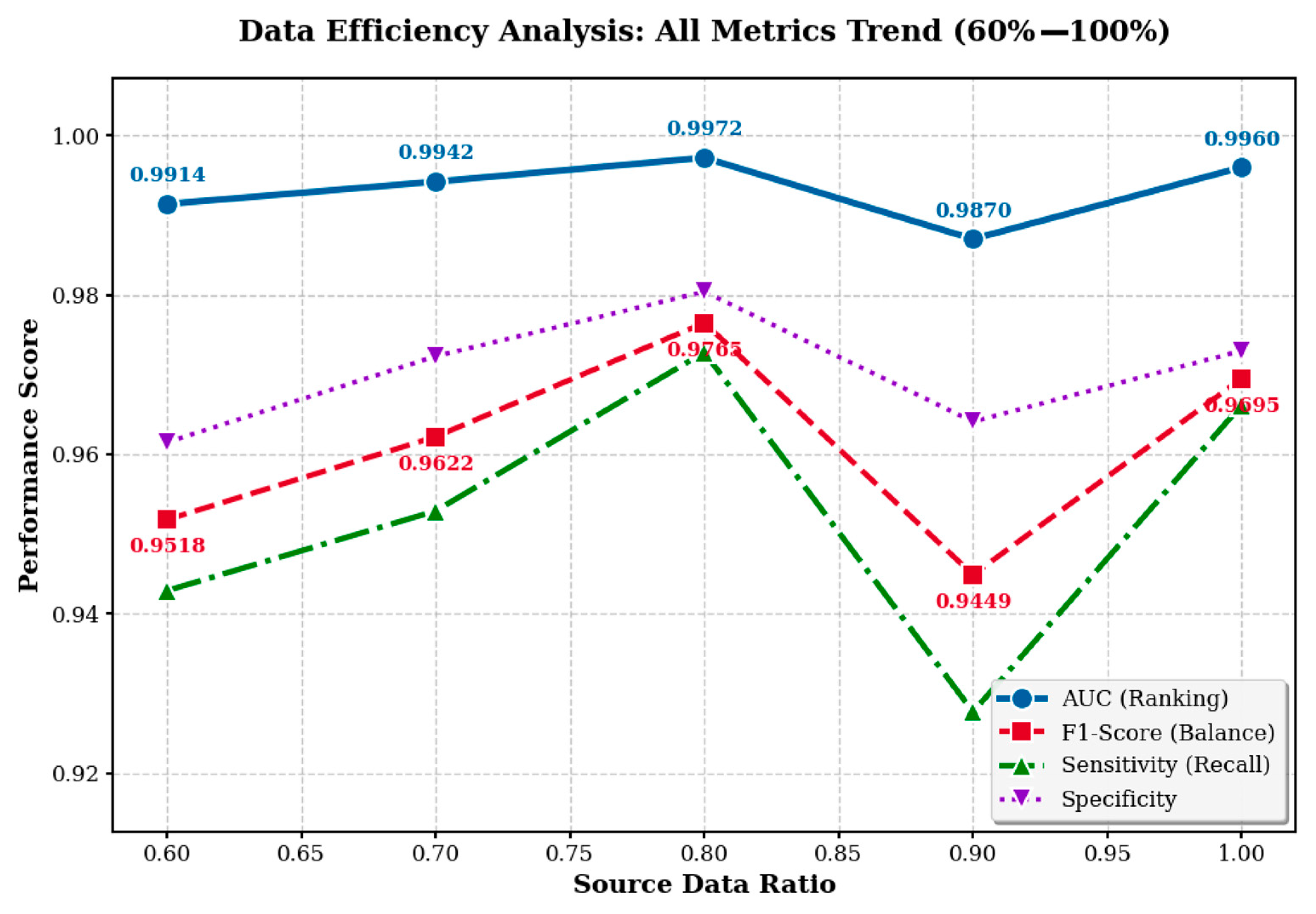

To construct the standardized input tensors required by deep CNNs and to capture the transient seizure features inherent in neonatal EEG signals, continuous multi-channel EEG recordings were segmented into fixed-length time windows. Given that neonatal seizures typically manifest as short-duration, paroxysmal rhythmic discharges and that the signals exhibit high non-stationarity, a sliding window technique was employed to segment the preprocessed 18-channel EEG signals. Specifically, the duration of each window was set to 2 s, which corresponds to 256 sampling points in the time domain at a sampling rate of 128 Hz. To mitigate the risk of overfitting on limited medical data, we applied a 50% overlap to the sliding windows specifically as a data augmentation strategy during the training phase. Crucially, the subsequent 5-fold cross-validation is strictly subject-independent, ensuring that no correlated overlapping segments exist between the training and validation sets, thereby preventing data leakage. This short-window design also ensures that the statistical properties of the signal remain relatively stable within a localized time scale, thus satisfying the fundamental assumptions of subsequent spectral analysis. Following the subject selection and sliding window segmentation processes, the final experimental dataset comprised a total of 16,514 samples. This substantial data volume provides a robust foundation for deep model training. Furthermore, to guarantee label consistency, the class label

for each window was determined exclusively by the expert consensus at the central time point of the window. This rule explicitly resolves the classification of windows straddling seizure onset or offset boundaries: the label is strictly dictated by the state of the central second, regardless of the boundary position. This ensures that the label corresponds to the core content of the segment. We acknowledge that this central-point labeling strategy effectively acts as a duration filter. While it may exclude extremely short events (<2 s) that do not overlap with the window center, this trade-off is intentional. It prioritizes label specificity, ensuring that the model is trained on high-confidence pathological patterns rather than ambiguous transient artifacts. In the feature extraction phase, traditional time-domain analysis often fails to fully reveal the complex evolutionary patterns of seizure signals in the frequency domain. Conversely, while Power Spectral Density (PSD) estimation effectively reduces noise, it sacrifices critical temporal information through time-averaging operations, rendering it incapable of reflecting dynamic frequency changes during seizure events. In light of this, this study employed the STFT to convert one-dimensional time series into two-dimensional Time-Frequency Spectrograms, thereby simultaneously preserving both spectral characteristics and temporal evolution information. STFT was applied to each 2-s EEG segment using a Hann window to minimize spectral leakage. The number of Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) points (

) was set to 64, and the sliding hop length was set to 16. No manual zero-padding was applied; boundaries were handled via standard centering. Given the sampling rate of 128 Hz, this configuration yields a frequency resolution of 2 Hz. This choice explicitly favors temporal resolution over fine-grained spectral detail, enabling the effective capture of transient high-frequency spikes while maintaining sufficient resolution for low-frequency (0.5–30 Hz) pathological slow waves. Following the STFT transformation, the complex spectrum was obtained, and the natural logarithm of its magnitude was computed to compress the immense dynamic range of EEG signals and ameliorate data distribution skewness. Consequently, each EEG window was transformed into a 3D tensor with dimensions of 18 × 33 × 17, where 18 represents the number of spatial electrode channels, 33 denotes the frequency components, and 17 indicates the time steps. This time-frequency representation not only filters out a portion of background noise but also accentuates the regions of energy concentration associated with seizure onset. To accelerate neural network convergence and eliminate amplitude discrepancies between patients, Z-score normalization was further applied to the generated spectrograms, standardizing them to a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. Through the aforementioned processing pipeline, raw physiological signals were converted into feature maps encapsulating three-dimensional information—space, frequency, and time—providing high-quality input data for the subsequent deep feature extraction based on ResNet. The detailed data preprocessing procedure is illustrated in

Figure 3.

2.3. Domain-Adversarial Spatiotemporal Network’s Entire Structure

2.3.1. Model Overview

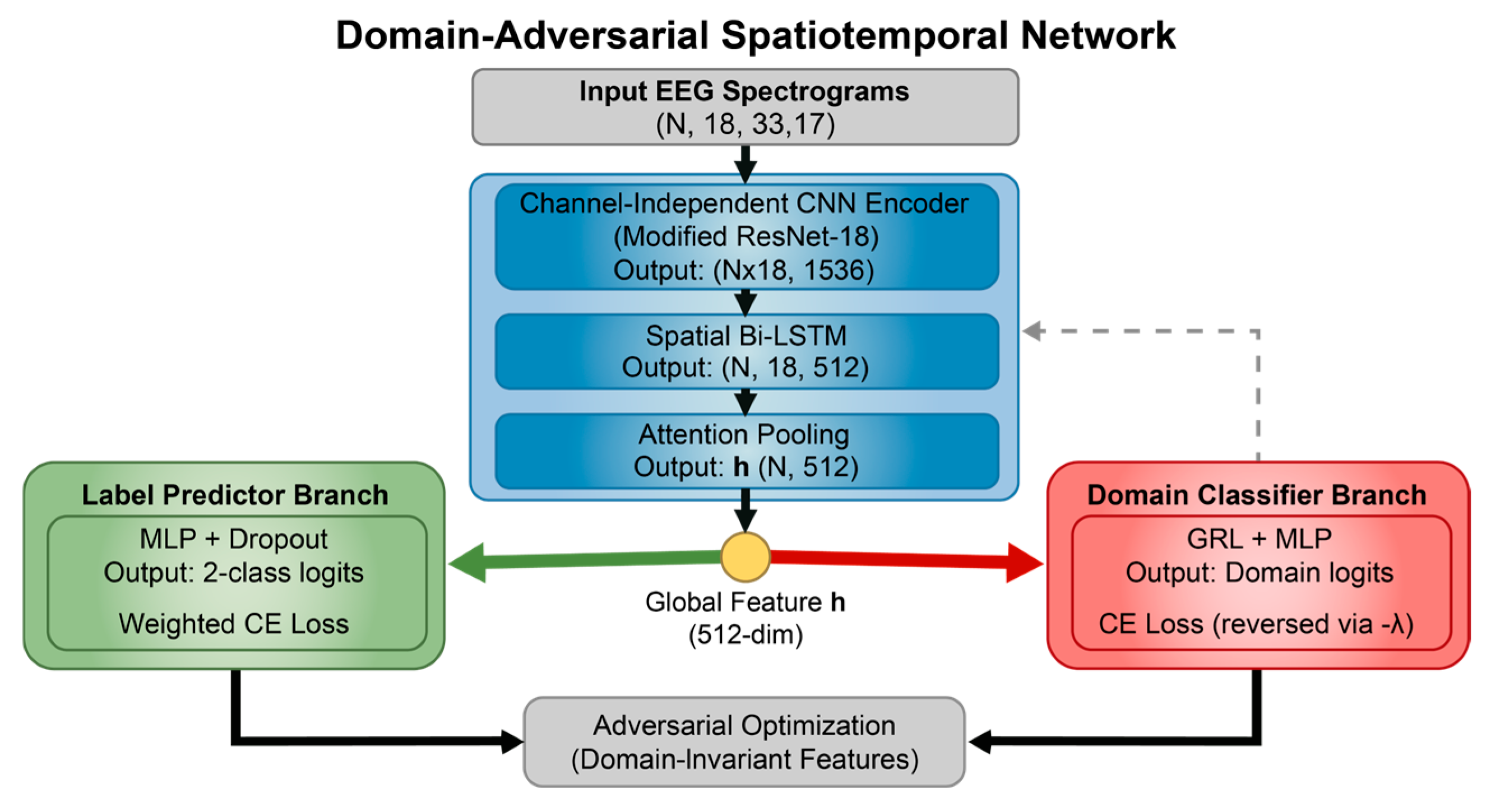

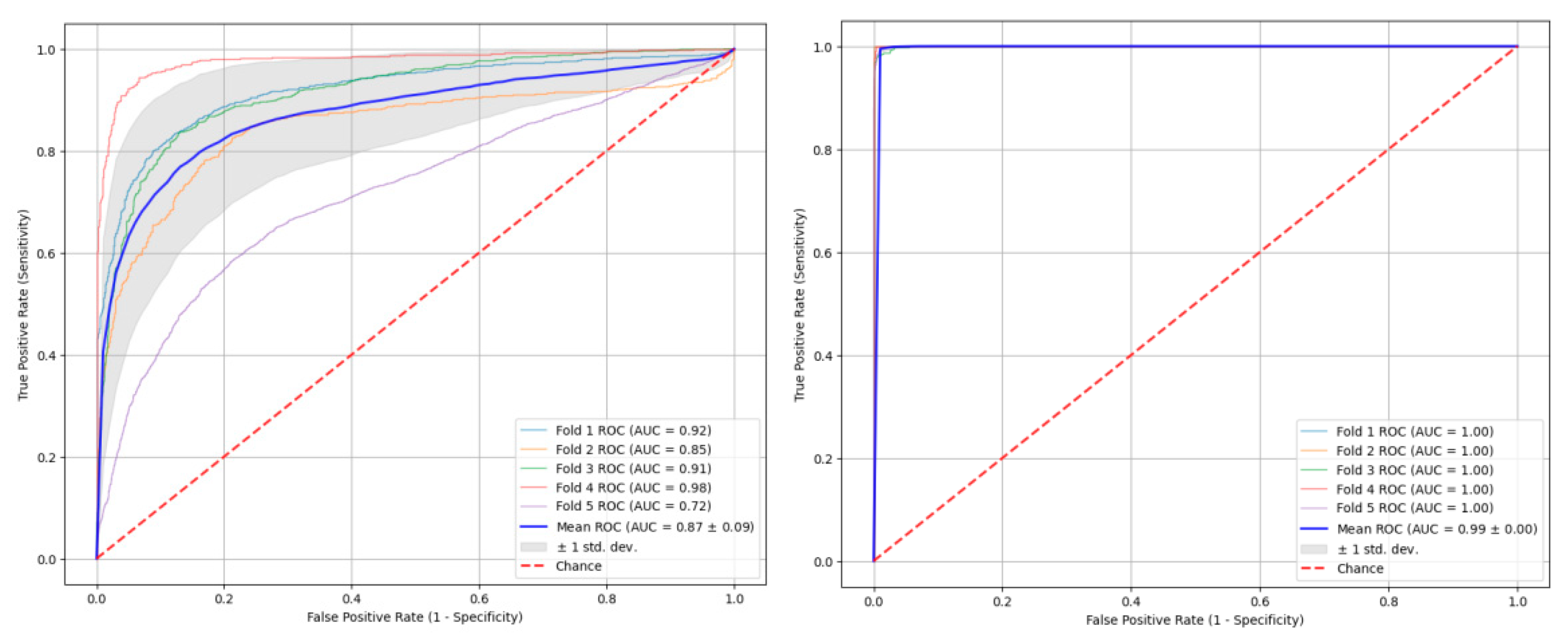

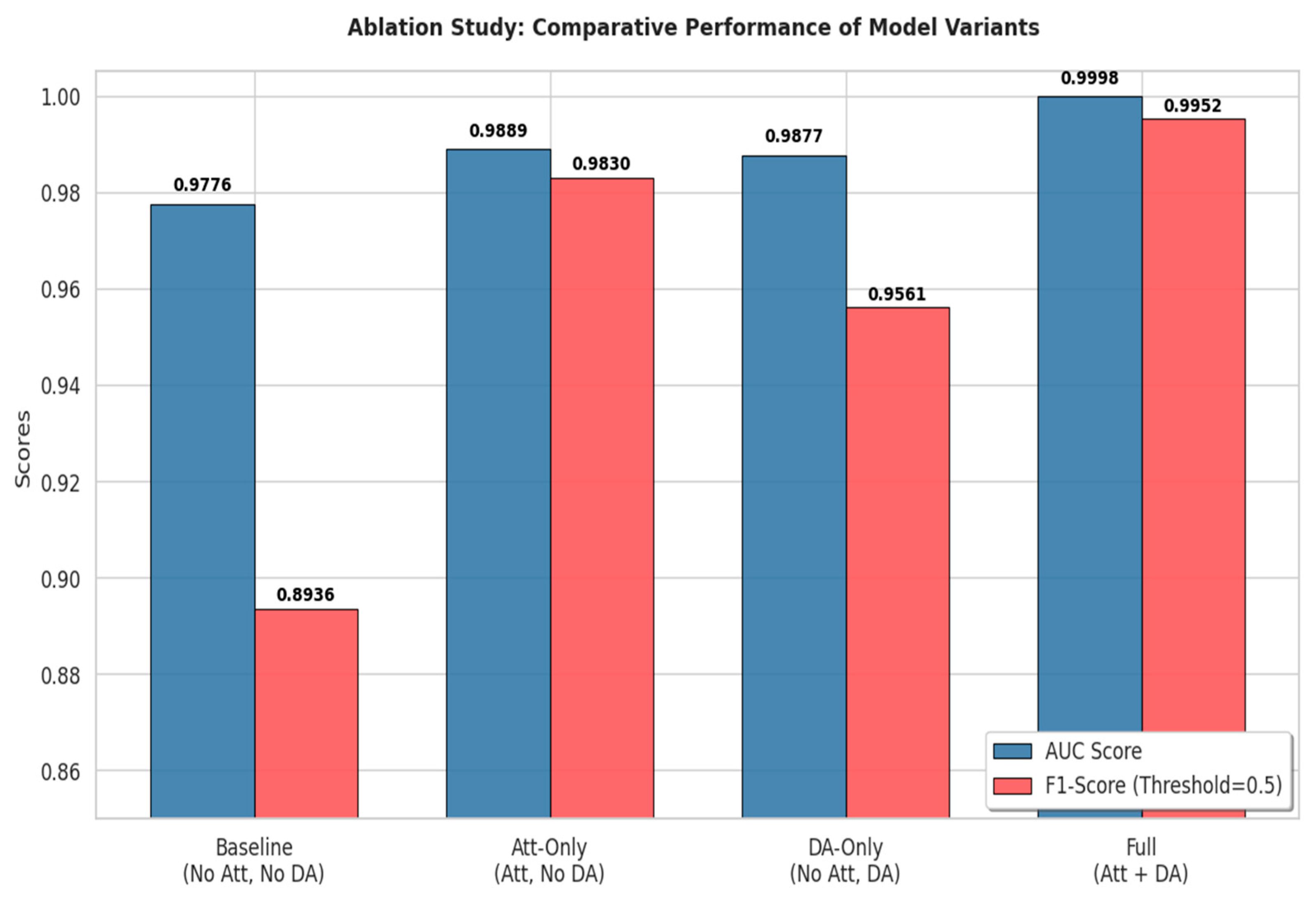

The DA-STNet constructed in this study is a deep neural network explicitly designed for cross-subject neonatal seizure detection. The network adopts a “shared backbone-dual branch” topology, aiming to concurrently process the recognition of seizure pathology and the obfuscation of subject identity. The model first utilizes a cascaded spatiotemporal feature extractor to map multi-channel EEG signals into a high-dimensional feature space. Subsequently, it introduces an adversarial mechanism via a GRL, establishing a competitive interplay between the main branch for label prediction and the adversarial branch for domain classification. This design effectively strips away individual identity information from the features while maintaining efficient feature extraction capabilities, thereby realizing a calibration-free, “plug-and-play” diagnostic solution.

Figure 4 illustrates the overall structure of the proposed DA-STNet.

The backbone network of the proposed model serves as the core feature extractor for the entire system, undertaking the task of transforming raw time-frequency spectrograms into highly abstract semantic vectors. Addressing the unique “time-frequency-spatial” composite structure of EEG signals, this backbone does not employ a monolithic network structure; instead, it utilizes a cascaded fusion of CNN and Attention mechanisms [

13].

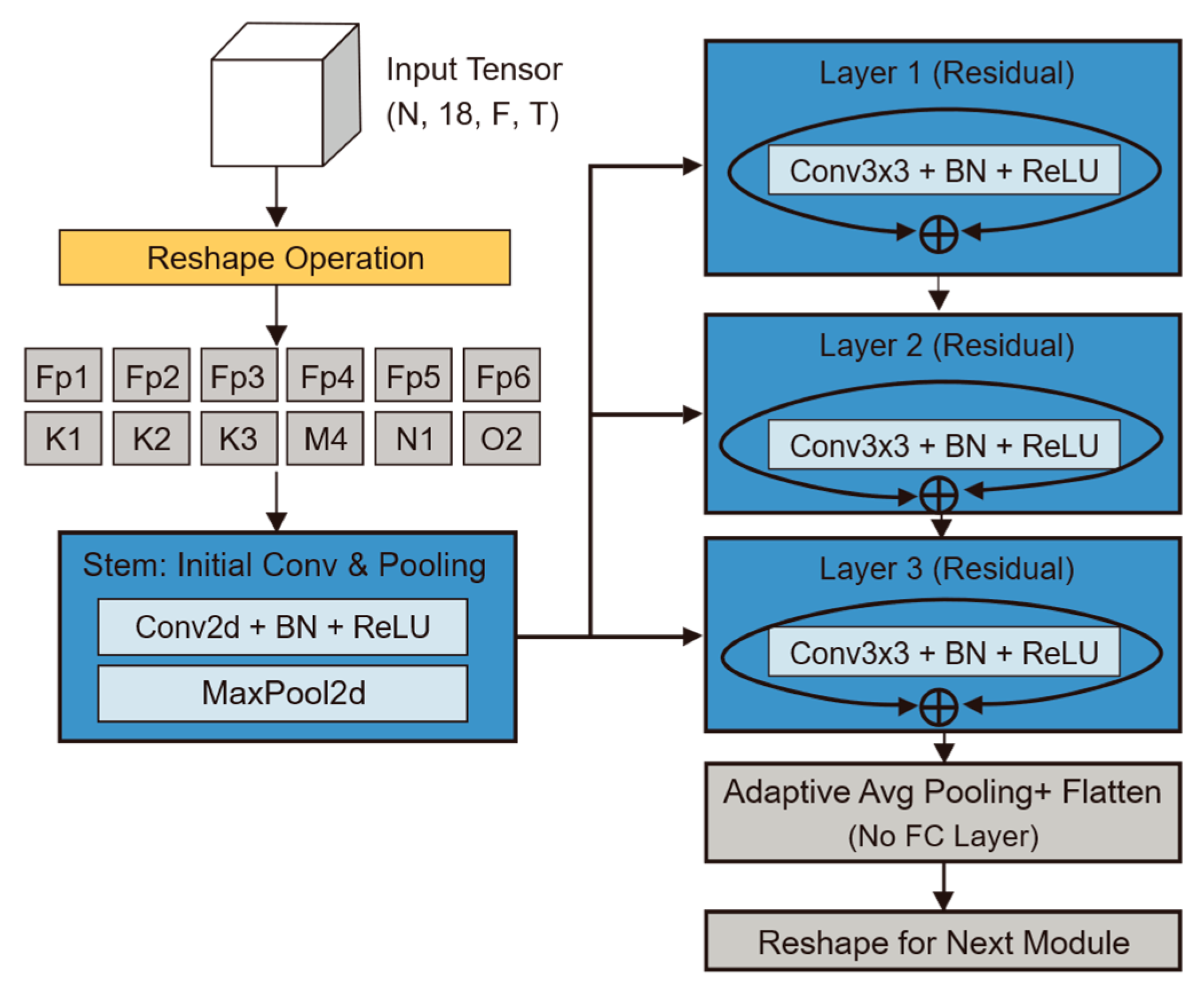

CI-CNN Encoder: Considering the batch training mechanism of deep learning, the model input is a four-dimensional tensor incorporating the batch dimension. The model first reshapes the input four-dimensional tensor into , dismantling the 18 electrode channels of each patient into 18 independent samples stacked along the batch dimension. The subsequent CNN shares weights across these independent single-channel spectrograms. The output of this stage is a tensor of shape , representing the independent local feature representations for each of the 18 channels.

Spatial Bi-LSTM: Following the extraction of local features for each electrode, the model arranges the 18 electrodes according to a specific topological order, treating them as a sequence of length 18. A Bi-LSTM module is employed to scan across this spatial sequence. Through this processing module, the feature dimension is reduced from 1536 to 512. This operation not only compresses information but also integrates global spatial topological knowledge.

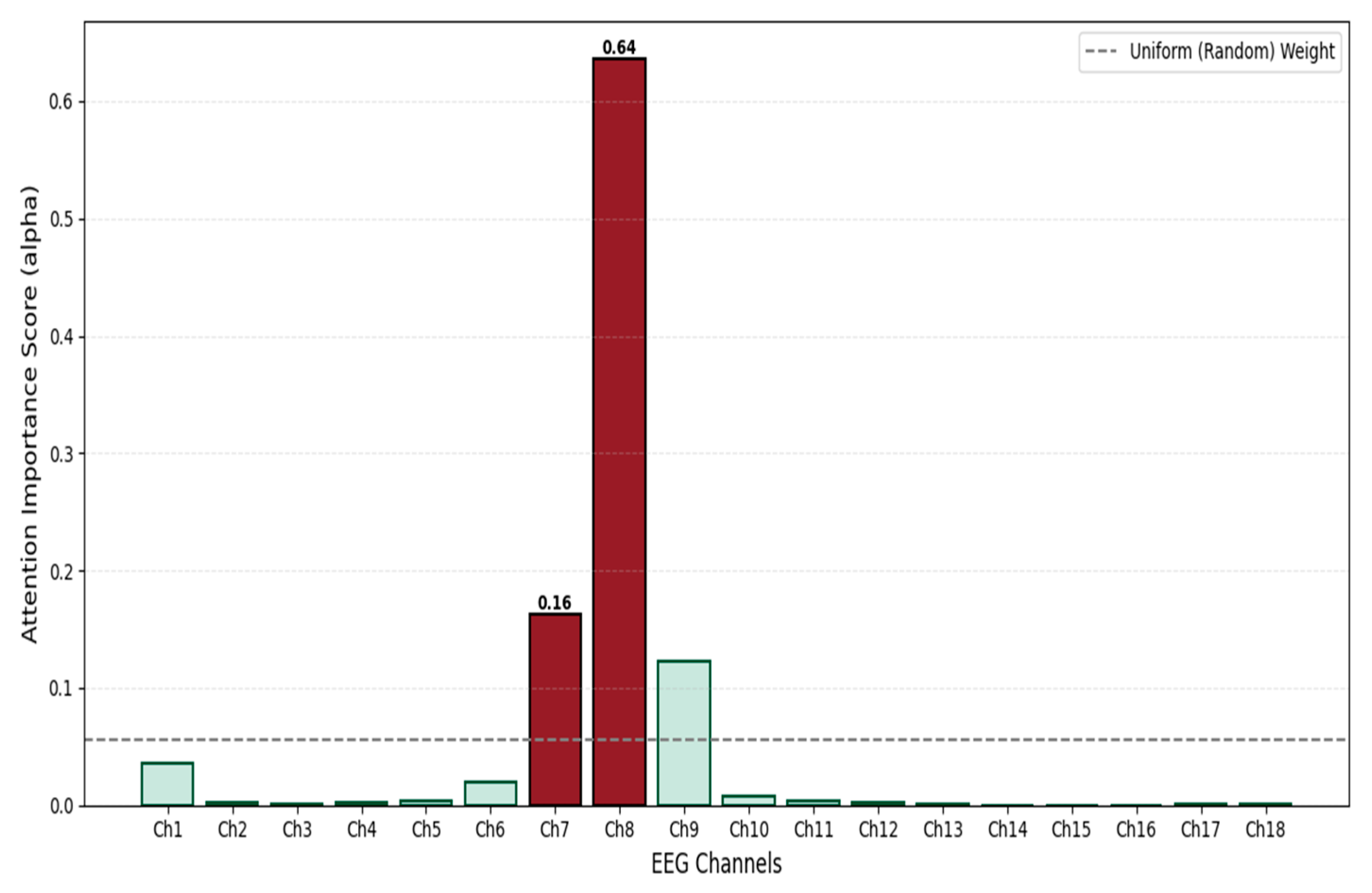

Attention Pooling: For the feature of each channel output by the Bi-LSTM, the attention module calculates a scalar score via a fully connected layer and normalizes it into a weight using a Softmax function. The model then aggregates information from all channels through weighted summation to generate a unique global feature vector. This 512-dimensional vector represents a high-level condensation of the entire EEG sample, providing the purest input for subsequent classification decisions.

The global feature vector output by the backbone network is immediately fed into two parallel task branches. The Label Predictor branch maps abstract features to the final “Seizure/Non-Seizure” diagnostic probability via a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP). Conversely, the Domain Classifier branch embeds a GRL at its input. This branch aims to strip away the subject identity information implicit in the features through gradient adversarial learning during backpropagation, ensuring that the model learns pathological representations that are universal across subjects rather than the specific “EEG fingerprints” of individuals.

2.3.2. Channel-Independent Convolutional Neural Network (CI-CNN)

The CI-CNN Encoder module plays the critical role of a “sensory frontend” within the overall architecture. By processing each electrode channel independently via a weight-sharing convolutional network, it decouples spatial information from time-frequency textures, compelling the model to focus on learning universal pathological morphological features rather than the electrode spatial distribution patterns specific to individual patients. Its core task is to extract high-dimensional texture features from the EEG time-frequency spectrograms processed by Short-Time Fourier Transform [

14].

To fully preserve the spatiotemporal-frequency characteristics of EEG signals, the model input is defined as a four-dimensional tensor

. Here,

represents the Batch Size during training; the spatial dimension

corresponds to the standard scalp electrode leads in the international 10–20 system, designed to capture spatial dependencies across different brain regions; the spectral dimension

covers the physiological frequency band of 0.5–30 Hz, aiming to encompass rhythm features with diagnostic significance; and the temporal dimension

represents the number of signal evolution frames within the short time window, preserving subtle temporal dynamics. To achieve “Channel-Independent” processing, a critical tensor reshaping operation is first executed to “fold” the spatial dimension

into the batch dimension

. The transformation

is defined as follows:

The geometric significance of this operation lies in the fact that the model no longer treats a sample as “one 18-channel image,” but rather as “18 independent single-channel images.” This design fundamentally severs the ability of the convolution operation to perceive spatial correlations at this stage, ensuring that feature extraction is based purely on local time-frequency textures.

The main body of the backbone network adopts the classic ResNet-18 architecture [

15]. However, tailored to the low resolution and single-channel characteristics of neonatal EEG spectrograms, we performed specific lightweight modifications. First, the number of input channels in the initial convolutional kernel was adjusted to 1 to accommodate grayscale time-frequency spectrograms. Second, to prevent overfitting or gradient disappearance when processing relatively simple EEG texture features, we removed the deeper Layer 4 and the fully connected layer from the original architecture, retaining only Layer 1 through Layer 3 for hierarchical feature extraction. Building on this, this study introduces a Channel-wise Weight Sharing mechanism. Let

denote the mapping function of the improved ResNet-18 with parameters

. For the input of the

-th electrode channel of the

-th sample, denoted as

, the feature extraction process can be formally expressed as

. Since all

channels share the same set of parameters

, this mechanism is not only equivalent to expanding the training data volume by a factor of

, thereby enhancing the model’s generalization capability on small-sample medical data, but also endows the model with Spatial Translation Invariance. Regarding the computational scaling capability, this ‘folding’ strategy implies that the computational complexity scales linearly (

) with the number of electrode channels. Unlike spatial-mixing architectures, where complexity often grows quadratically (

), our design ensures efficient scalability. Crucially, although folding increases the effective batch size by a factor of 18, the removal of the computationally intensive Layer 4 and fully connected layers effectively offsets this load, ensuring that the model’s resource consumption remains within a lightweight range suitable for clinical deployment.

Through layer-by-layer abstraction via ResNet residual blocks, the original two-dimensional spectrograms are mapped into high-dimensional feature maps. Subsequently, through adaptive average pooling and flattening operations, each channel outputs a high-dimensional vector. Specifically, the feature tensor output at the end of the backbone network contains 512 feature channels and retains 3 units of spatial information in the frequency domain. To align the features for input into the subsequent temporal module, a flattening operation is executed to unroll this tensor into a one-dimensional vector, the dimension of which is derived from the product of the channel count and the spatial dimension (

). Therefore, for the

-th channel of the

-th sample, its feature representation can be formally defined as:

The 1536-dimensional vector here serves as a highly condensed representation of the signal state for that channel within the current time window. Before transmitting the data to the subsequent module, we need to execute the inverse reshaping operation

to restore the spatial structure of the data:

At this stage, although the output tensor

contains features from all channels; these features remain isolated from one another. The CNN encoder is exclusively responsible for discerning the local details of each electrode, while disregarding the connections between electrodes. This establishes the foundation for the subsequent module, namely the Bi-LSTM. The detailed structure/results of this module are presented in

Figure 5.

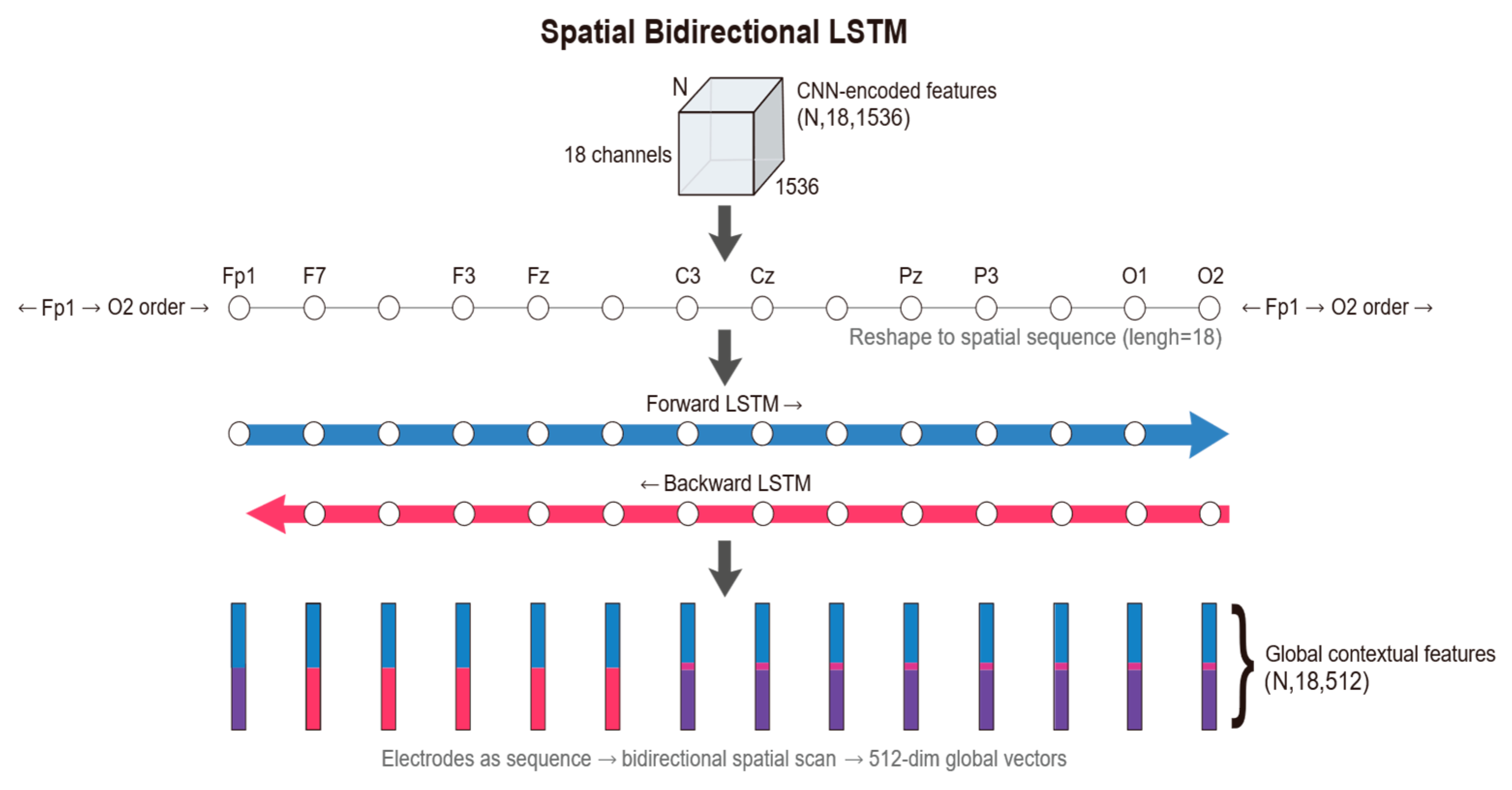

2.3.3. Spatial Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM)

While the CNN encoder in the previous stage effectively extracted the microscopic time-frequency textures within each electrode, its “Channel-Independent” processing paradigm physically severed the inherent spatial continuity of EEG signals. Given that a seizure is essentially a global event involving abnormal synchronization and propagation across widespread brain networks, relying solely on local features makes it difficult to distinguish isolated artifacts from genuine pathological discharges [

16]. To reconstruct the topological dependencies and functional coupling between electrodes, this study introduces the Spatial Bi-LSTM [

17] module, aiming to fuse discrete local features into a spatial representation equipped with global context. The Spatial Bi-LSTM uses

as the sequence length to scan

, thereby rebuilding the brain’s topological connectivity network among the independent local features [

18].

First, regarding input reshaping and sequence definition, we perform a view reshaping operation on the flattened tensor output by the CNN, denoted as

, to restore it to the sequence format

In this representation, the dimension

is redefined as the sequence length. Based on the “Space-as-Sequence” modeling hypothesis, we treat the electrodes arranged according to the international 10–20 system as a fixed spatial sequence. This strategy is biologically inspired by the clinical ‘Double Banana Montage’ reading protocol, where neurologists scan EEG channels in specific longitudinal chains to identify propagation. Unlike Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) that require calculating dense adjacency matrices (

), this sequence-based approach maintains linear complexity (

) while effectively capturing inter-hemispheric symmetry. It is important to note that while RNNs are sensitive to sequence order, ‘Permutation Invariance’ is not a requirement for standard EEG montages. Since the physical locations of electrodes are fixed under the 10–20 system, fixing the input sequence ensures consistent spatial feature extraction, analogous to how CNNs process fixed pixel grids in images. Secondly, based on the bidirectional spatial scanning mechanism [

19], as well as the symmetry of the brain’s hemispheric anatomical structure and volume conduction effects, the dependencies between electrodes are inherently undirected. Therefore, we adopt a bidirectional structure to conduct a panoramic scan along the spatial axis. For the input sequence of the

-th sample,

, the model simultaneously maintains hidden state updates in two directions:

Here,

captures the forward spatial dependency from the frontal lobe to the occipital lobe, while

captures the backward contextual information. The gating mechanism internal to the LSTM unit plays a key role in this process, capable of adaptively suppressing spatial background noise during cross-hemisphere transmission. Finally, for feature fusion and output, the module generates the output vector

for the

-th electrode by concatenating the hidden states from both directions. In this study, we set the hidden layer dimension to 256; thus, the output feature dimension is 512. The output tensor generated through this process achieves a qualitative leap: each channel ve

ctor

is no longer confined to a local receptive field but instead integrates global information regarding the whole-brain topological structure. These compact contextual features not only resolve the limitations of the local perspective but also provide a solid foundation for robust channel weighting in the subsequent attention pooling layer.

Figure 6 illustrates the schematic of the Spatial Bi-LSTM.

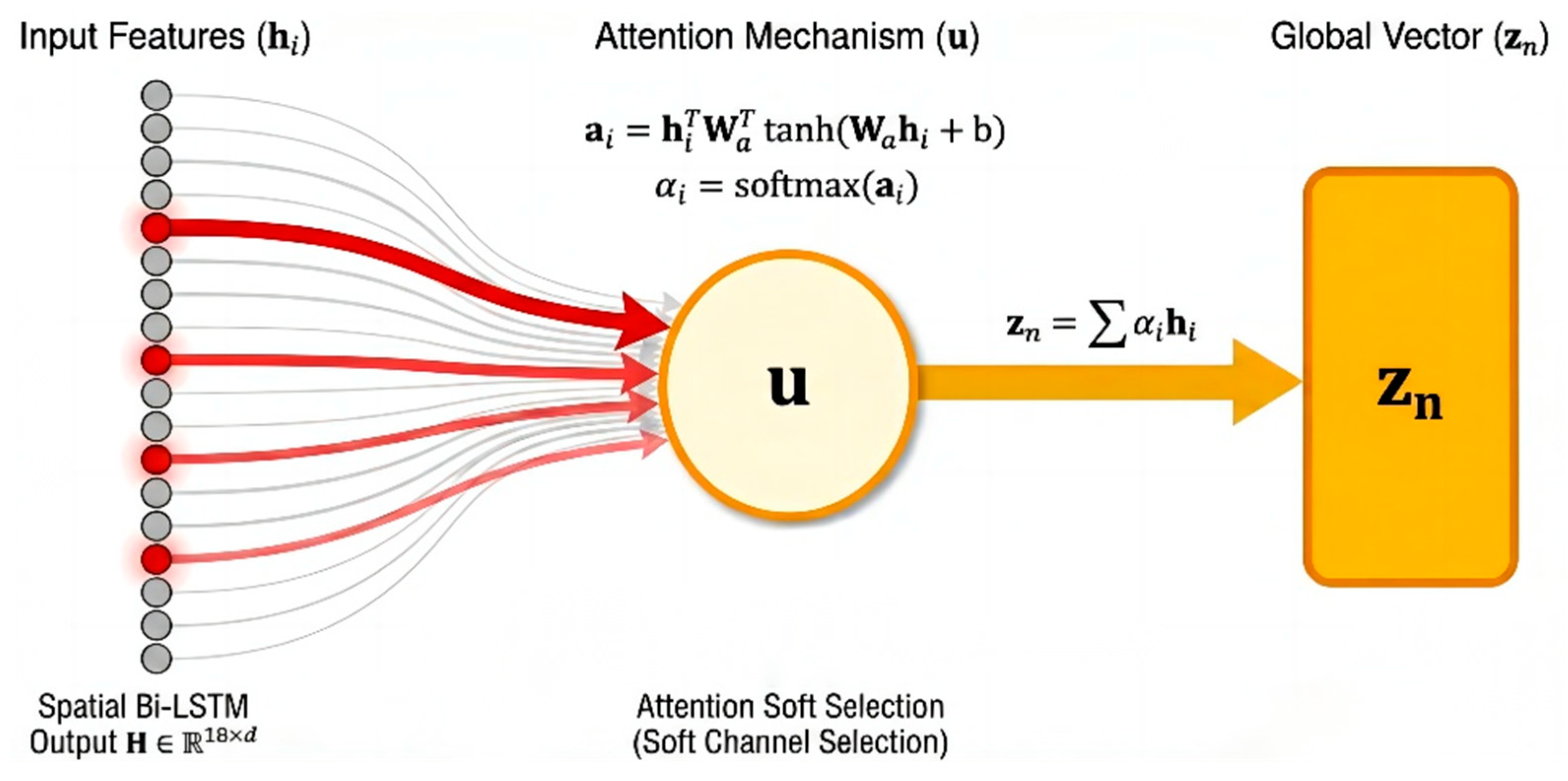

2.3.4. Attention Pooling Layer

Although the Spatial Bi-LSTM effectively captures the topological dependencies between electrodes, the contribution of different channels to seizure detection often varies significantly. Given that neonatal seizures frequently manifest as focal onsets, and EEG signals are susceptible to local interference from electrode detachment or motion artifacts, directly applying average pooling to all channels may dilute critical pathological information. To achieve dynamic signal-to-noise separation and global semantic compression, this study introduces an Attention Pooling Layer [

20] based on the philosophy of Multiple Instance Learning (MIL). This module empowers the model to autonomously evaluate channel importance, aiming to fuse the variable-length spatial sequence features into a compact global representation through weighted integration. Attention scoring [

21] and weight assignment are set as follows: The feature tensor output by the Spatial Bi-LSTM is

. For the feature vector

of the

-th electrode in the

-th sample, we first calculate its attention score via a gating mechanism-based non-linear function:

In this formula,

and

are learnable projection parameters used to map features into the hidden attention space;

serves as the context vector, acting as a “pathological pattern expert” to evaluate the degree of matching between local features and seizure patterns. Subsequently, the Softmax function is utilized to normalize the scores, generating attention weights in the form of a probability distribution:

The weight

directly quantifies the relative contribution of the

-th channel to the final diagnosis. This mechanism realizes a “soft channel selection” strategy: the model is capable of adaptively assigning higher weights to channels containing pathological characteristics, such as spike-and-wave discharges [

22], while simultaneously suppressing those containing background noise or artifacts. This capability significantly enhances the system’s robustness within complex clinical environments. Finally, regarding global feature generation, we produce a unique global feature vector by performing a weighted summation over all channel features:

This operation compresses the sequence data containing spatial dimensions into a fixed 512-dimensional global semantic vector.

no longer contains explicit electrode location information but instead integrates the most salient pathological features of the whole brain. As the final output of the backbone network, it serves as the shared input for the subsequent Label Predictor branch and Domain Classifier branch, constituting the core vehicle for feature purification and adversarial learning within the DA-STNet architecture [

23].

Figure 7 illustrates the principle of the attention aggregation mechanism.

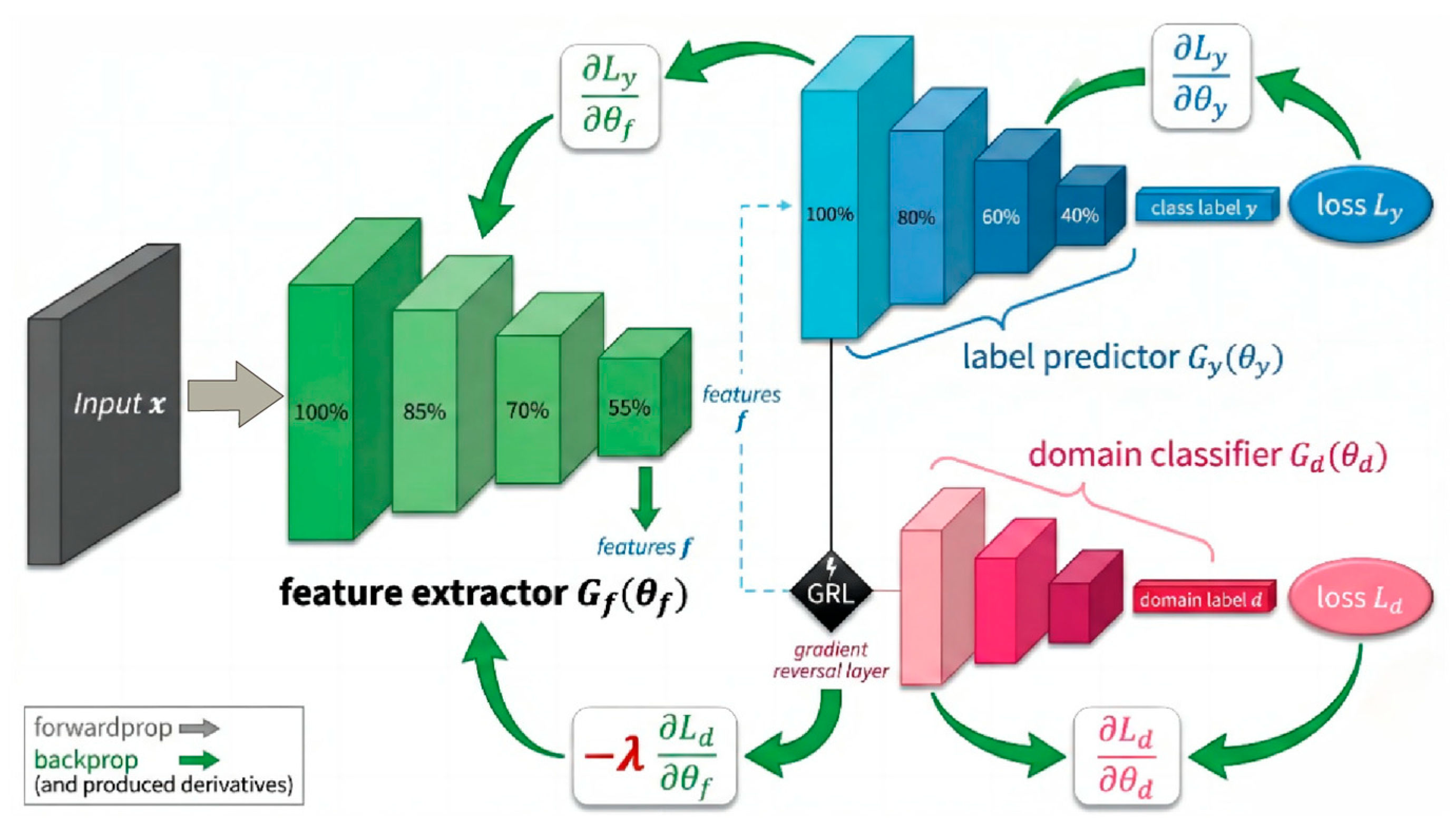

2.3.5. Label Prediction and Domain Classification Branch

At this stage, the network bifurcates into two parallel task branches: the Label Predictor (

) and the Domain Classifier (

). These two components collaboratively guide the parameter updates of the feature extractor

via an adversarial mechanism. The Label Predictor branch (parameterized by

) functions analogously to a “clinician,” designed to map high-level abstract features into a diagnostic decision space. Structurally, this branch is composed of a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP). It employs fully connected layers coupled with ReLU activation functions to perform non-linear transformations, and incorporates a Dropout layer to mitigate the risk of overfitting. The branch ultimately yields the classification label

, distinguishing between seizure and non-seizure states. Accounting for the inherent sparsity of seizure events in neonatal EEG monitoring (i.e., class imbalance), we adopt a weighted cross-entropy loss function, denoted as

, as the primary optimization objective:

Specifically, the weight parameter

is set to 2.5 to assign higher gradient importance to positive samples (seizures). This strategy compels the model to maintain high sensitivity towards subtle seizure signals during backpropagation, thereby effectively mitigating the bias introduced by class imbalance. Simultaneously, the Domain Classifier branch (parameterized by

) acts as an “identity detective,” dedicated to identifying the subject identity (domain label

) based on the extracted features

. To achieve cross-subject feature generalization, we embed a GRL at the input of this branch. During the forward propagation phase, the GRL performs an identity transformation, passing the feature

losslessly to the domain classifier to compute the domain discrimination loss

. Conversely, during the backpropagation phase, the GRL reverses the sign of the gradients flowing through it. As illustrated in

Figure 8, the update of the backbone parameters

is driven by the joint influence of two distinct gradient flows: the gradient from the Label Predictor,

, seeks to minimize diagnostic error; while the gradient from the Domain Classifier,

, is multiplied by a negative coefficient

as it passes through the GRL. This effectively converts the objective into a gradient ascent direction (

), forcing the encoder to generate subject-invariant features that confuse the domain classifier. This mechanism constructs a Min-Max Game: the domain classifier attempts to accurately distinguish subjects by minimizing

, whereas the feature extractor, under the influence of the GRL’s reverse gradients, is forced to update parameters in a direction that maximizes the domain classification error. As training progresses, the network eventually converges to a Nash Equilibrium: the extracted features

encompass pathological information capable of minimizing diagnostic error, while simultaneously stripping away identity-specific information that distinguishes individuals. This realizes true Domain Invariance and cross-subject generalization [

24].

Figure 8 illustrates the operational mechanism of the label prediction and domain classification branches.