MFPNet: A Semantic Segmentation Network for Regular Tunnel Point Clouds Based on Multi-Scale Feature Perception

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A Kernel Point Convolution (KPConv) architecture integrating multi-scale spatial features is designed, which unifies standard KPConv, Strided KPConv, and Multi-Scale KPConv into a bottom-up feature extraction framework combining dense and sparse representations. This enhances semantic modeling capabilities for structurally diverse targets across scales.

- (2)

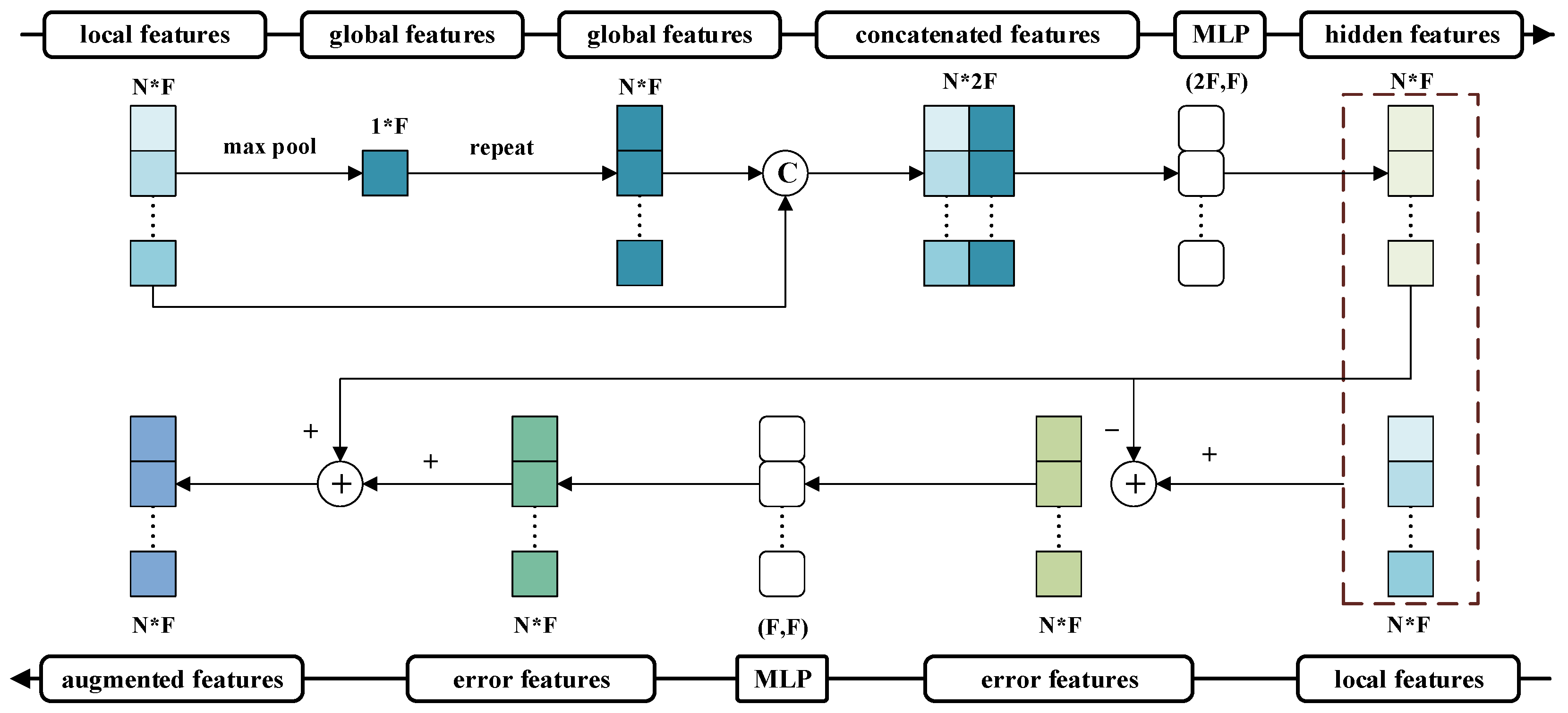

- A local-global feature fusion module based on error feedback was constructed. By introducing global context information to explicitly compensate and constrain the local features, it effectively alleviated the problems such as blurred boundaries and difficulty in distinguishing small-scale categories in tunnel scenarios, and improved the consistency and discriminability of multi-layer feature representations.

- (3)

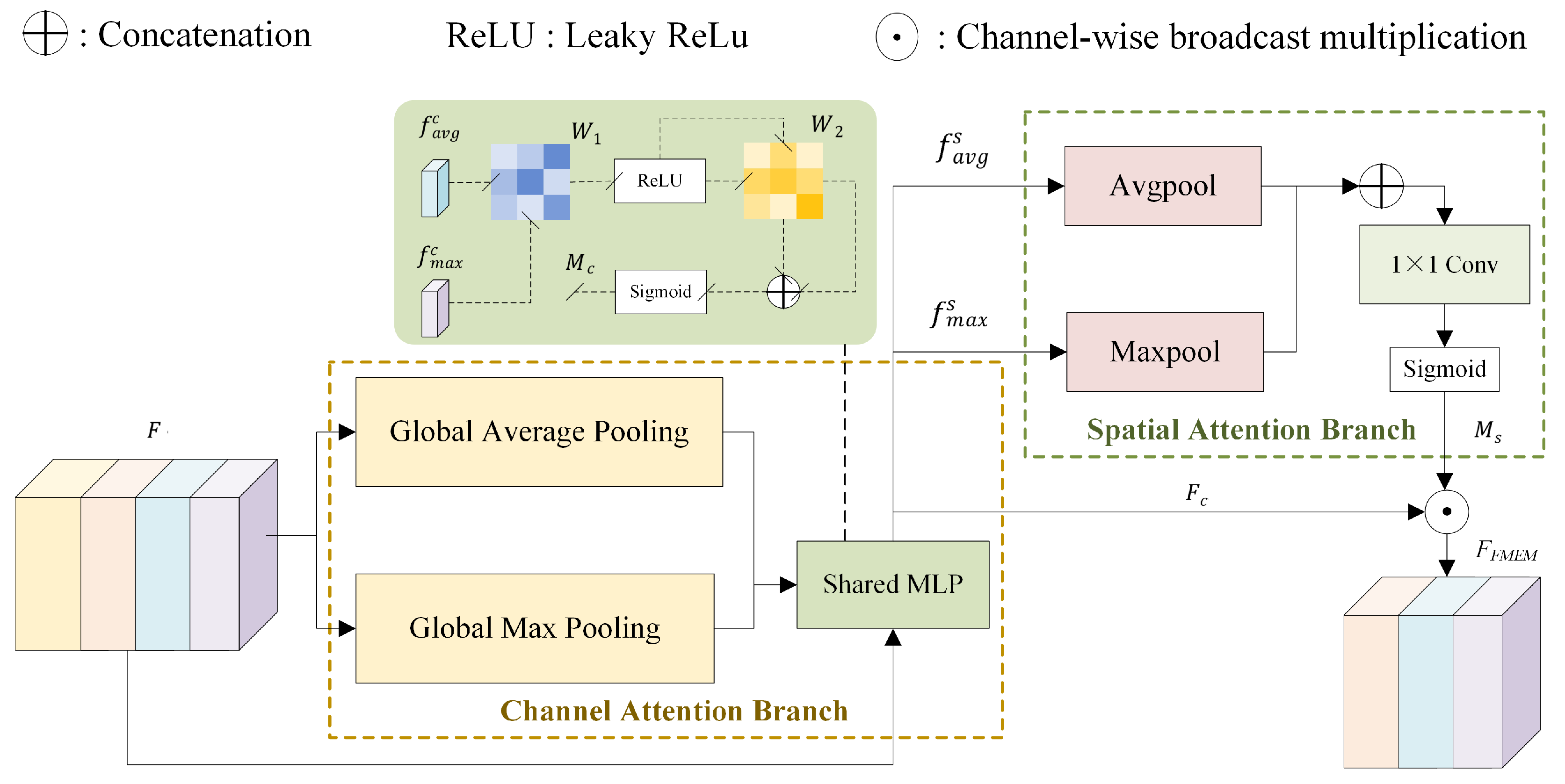

- Introduce a dual-branch enhancement mechanism based on feature modulation. By jointly modeling the semantic correlation of the channels and the spatial response distribution, the multi-scale fused features are adaptively re-calibrated and structurally enhanced, thereby further strengthening the discriminative semantic expression of key components.

2. Related Work

2.1. Projection-Based or Voxel-Based Methods

2.2. Point-Based Methods

3. Materials and Methods

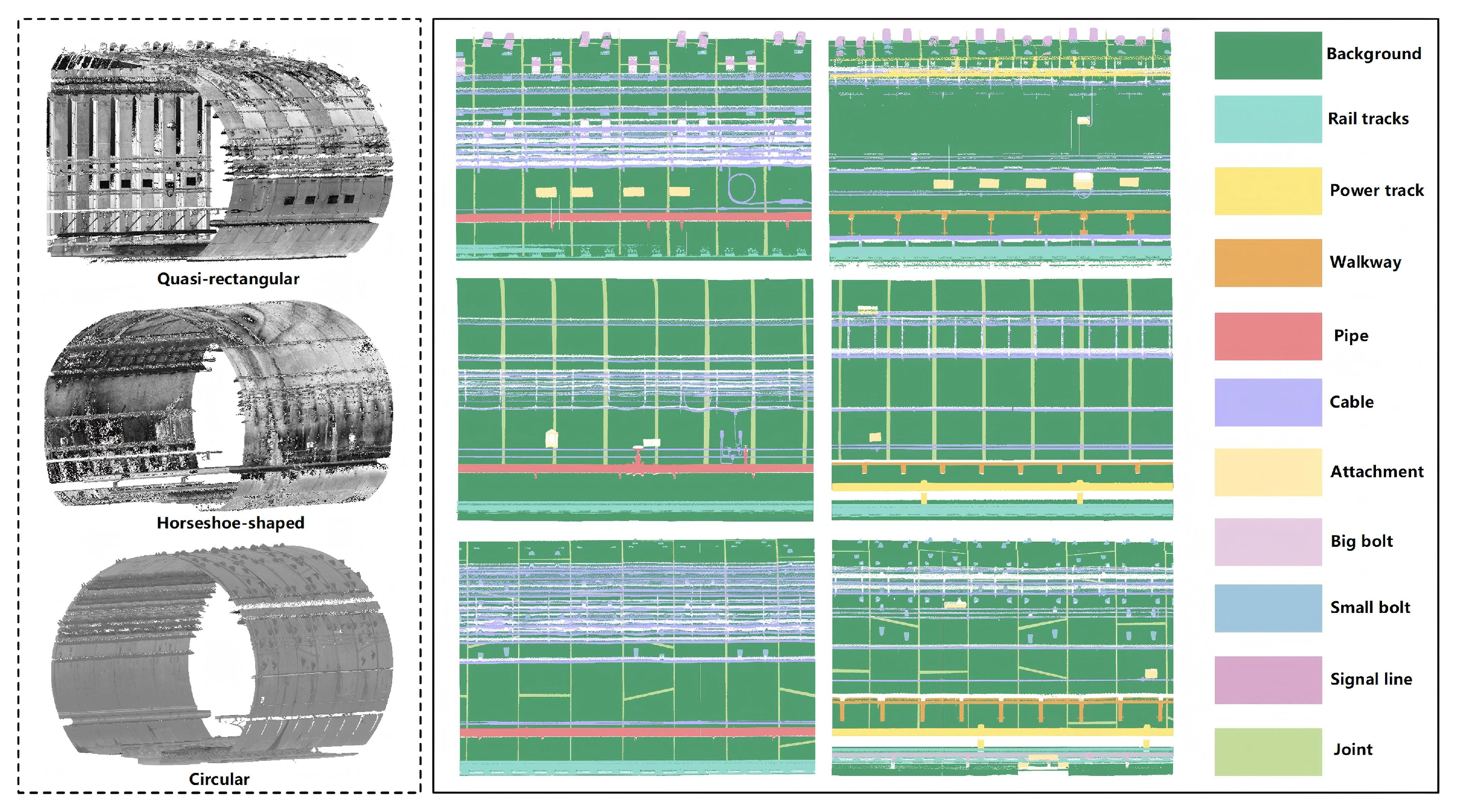

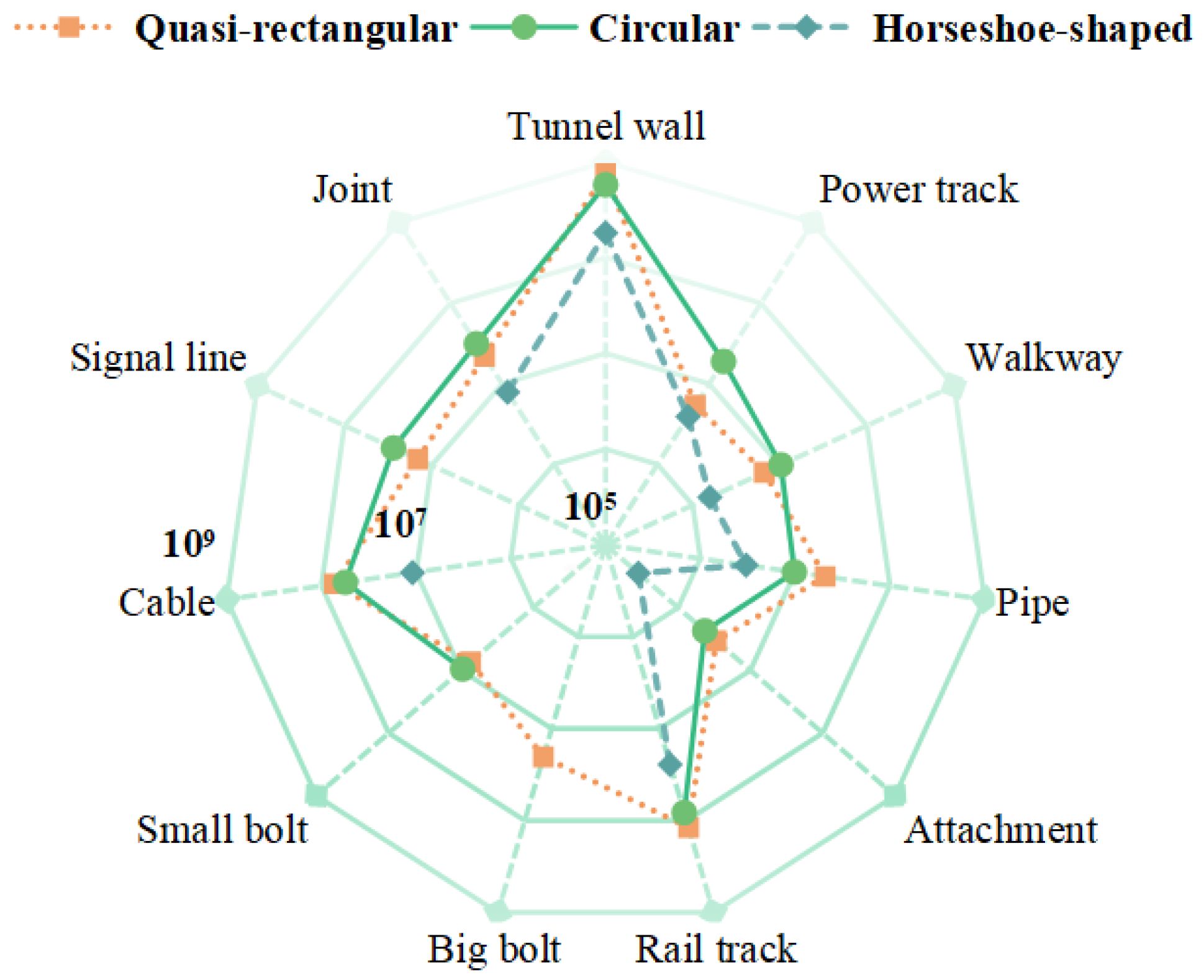

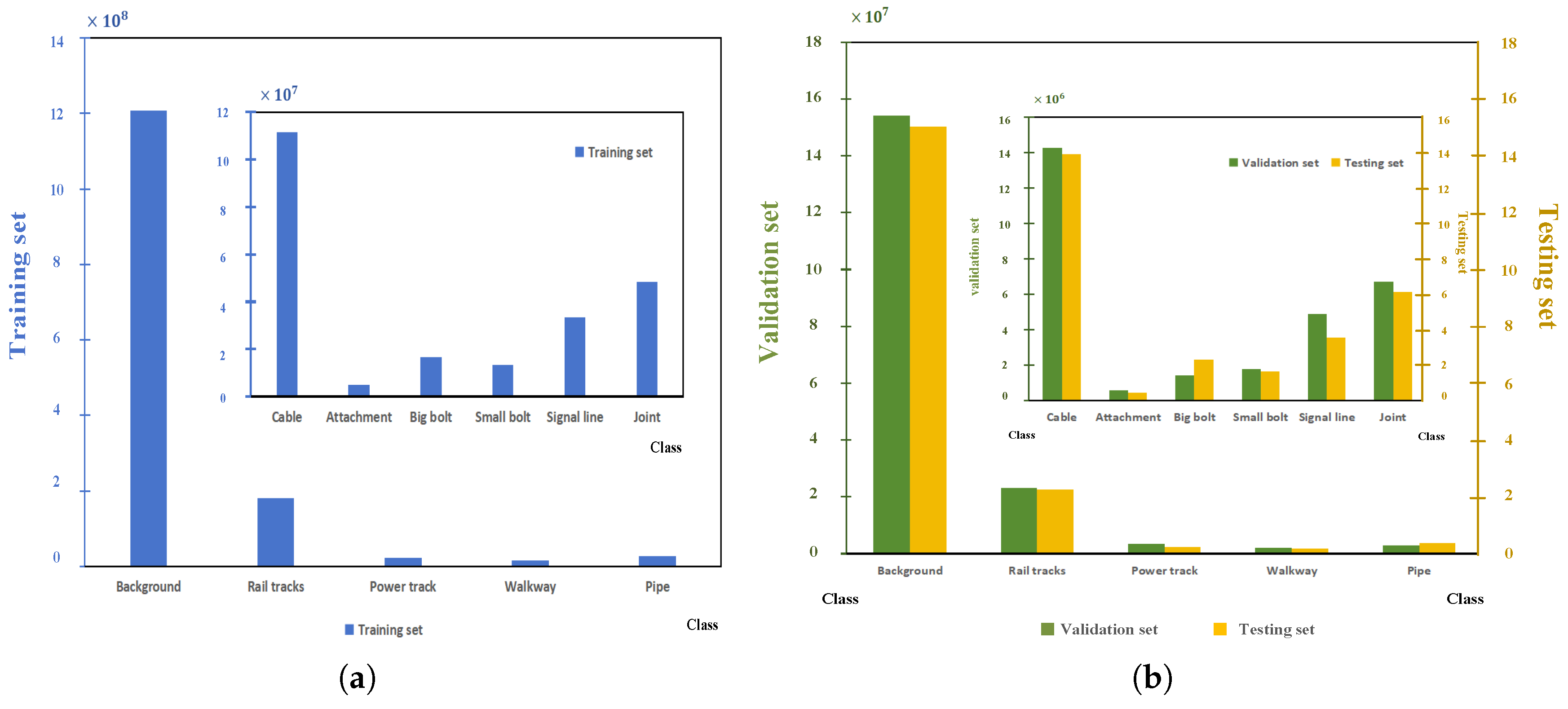

3.1. Dataset

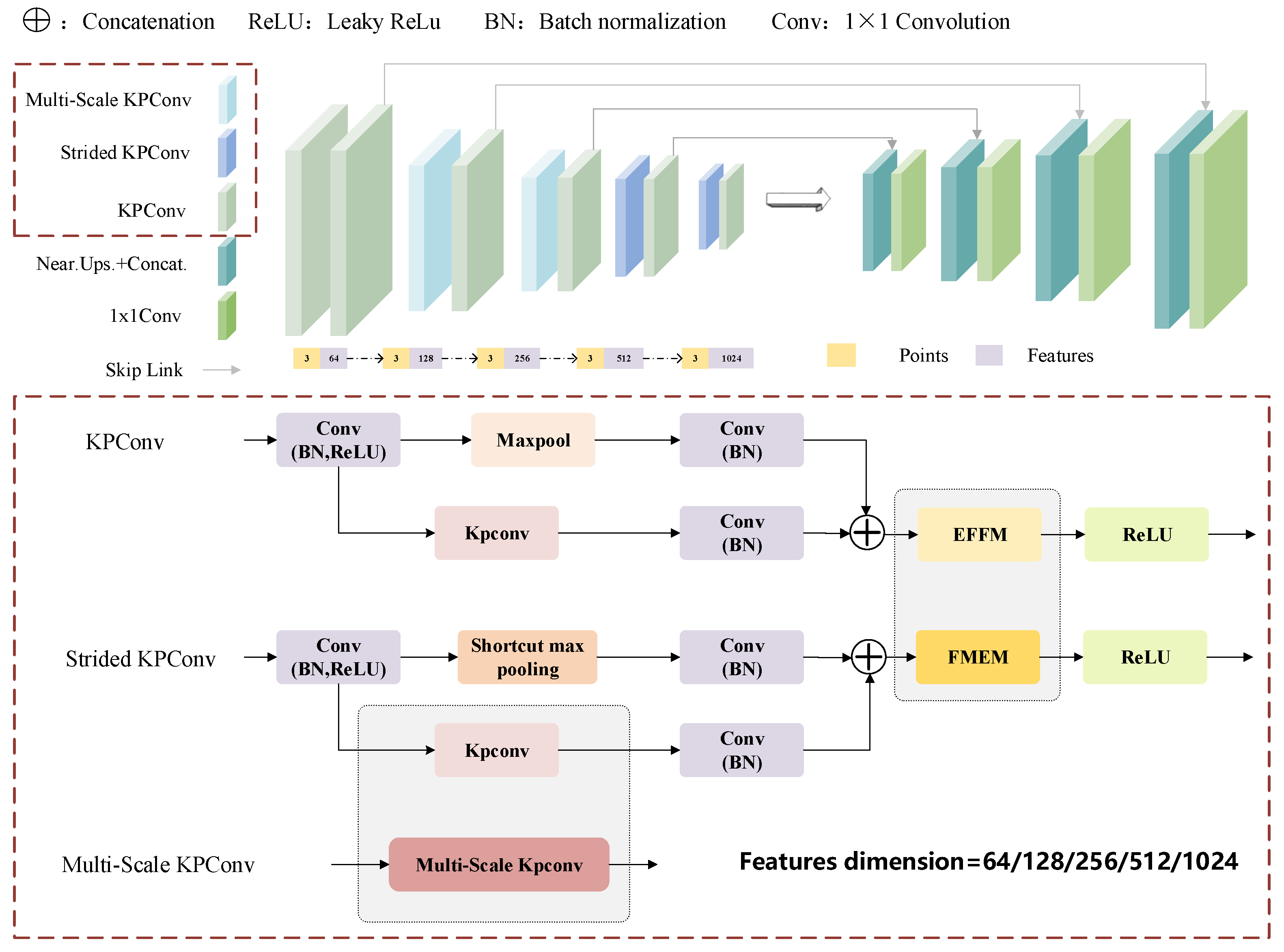

3.2. MFPNet Network Architecture

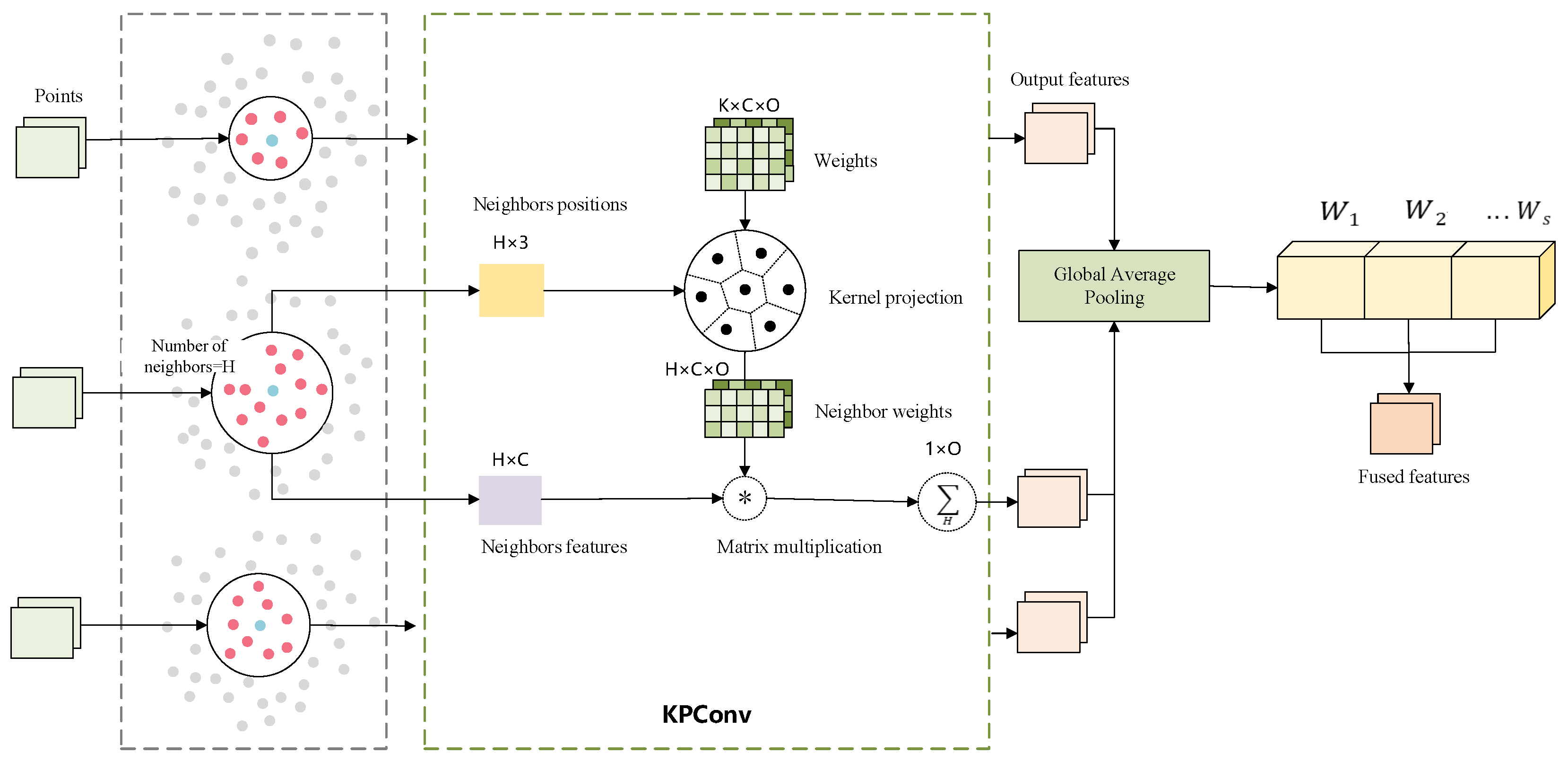

3.2.1. Multi-Scale Kernel Point Convolution

3.2.2. Error Feedback Fusion Module

3.2.3. Feature Modulation and Enhancement Module

4. Experiments and Evaluation

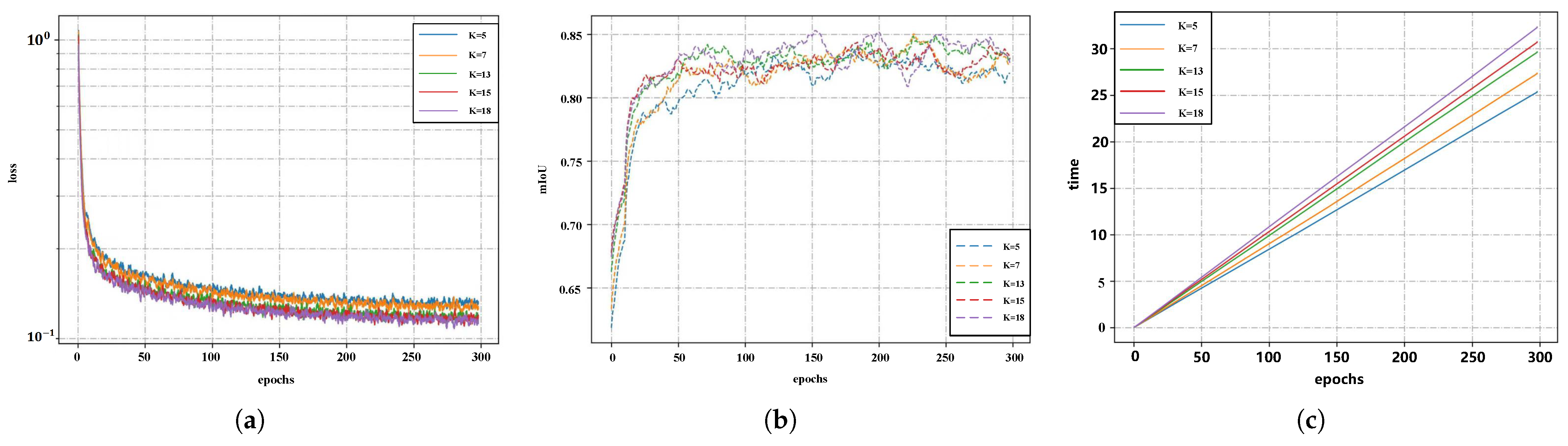

4.1. Environment and Data

4.2. Evaluation Criteria

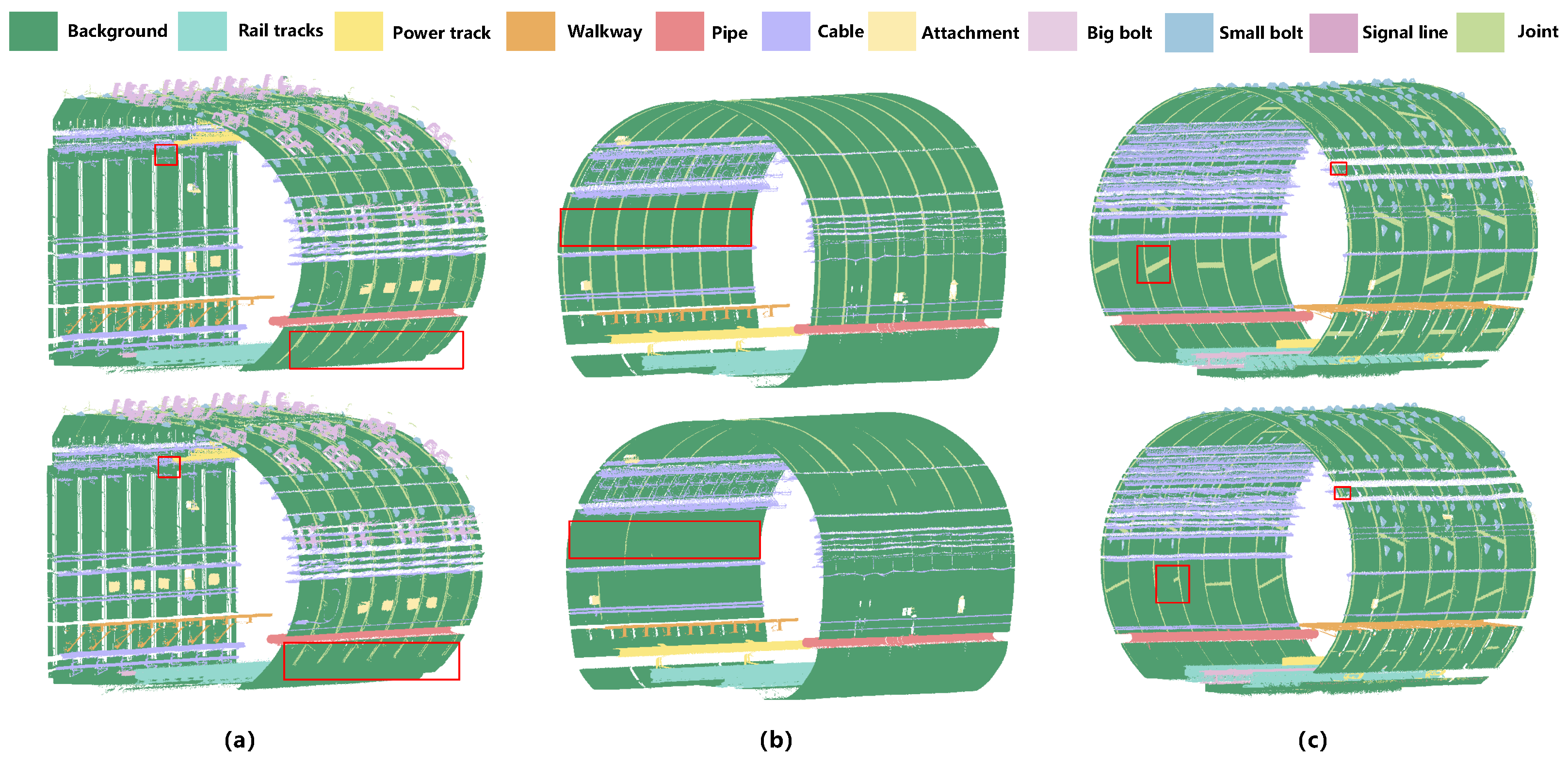

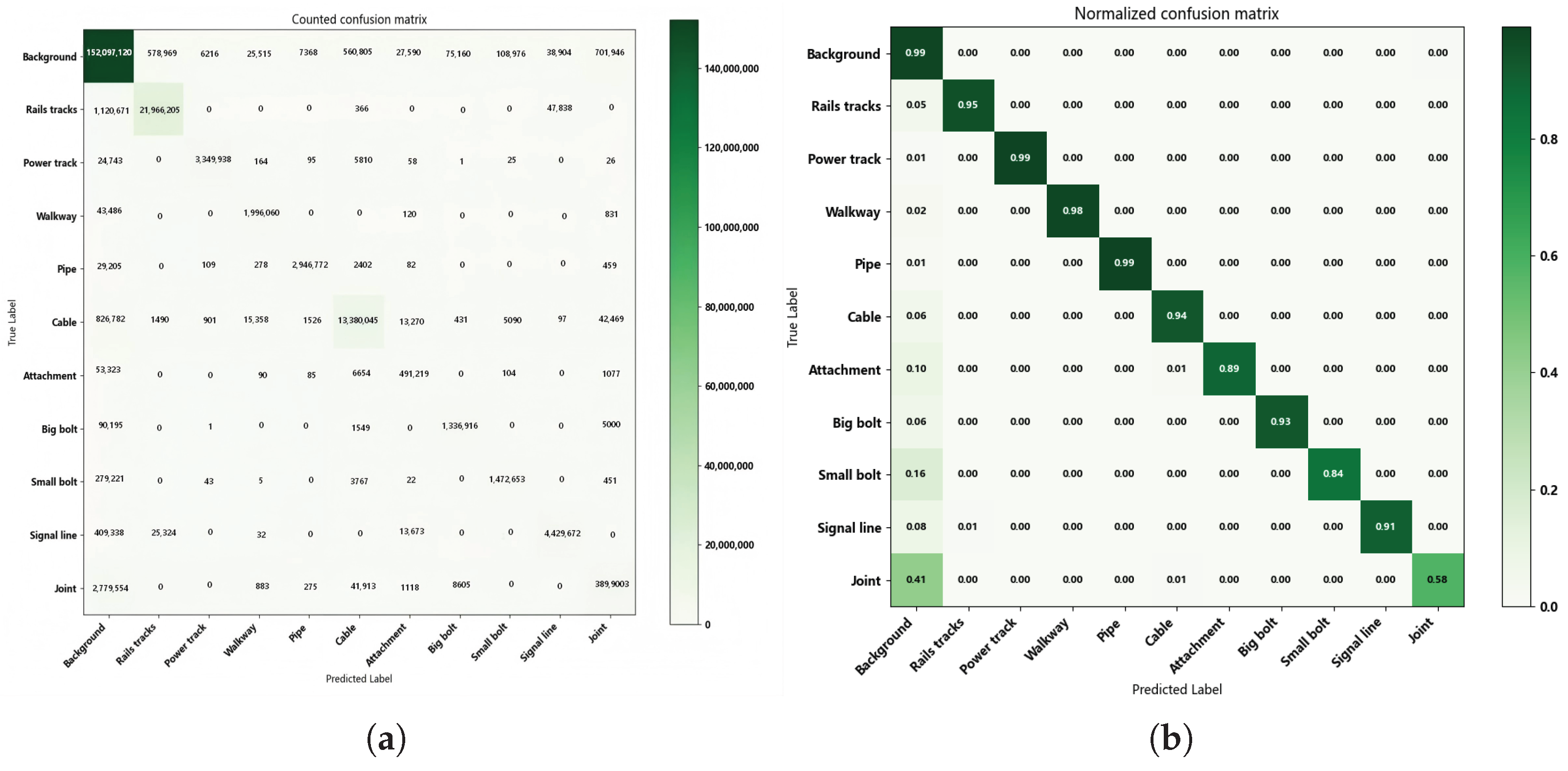

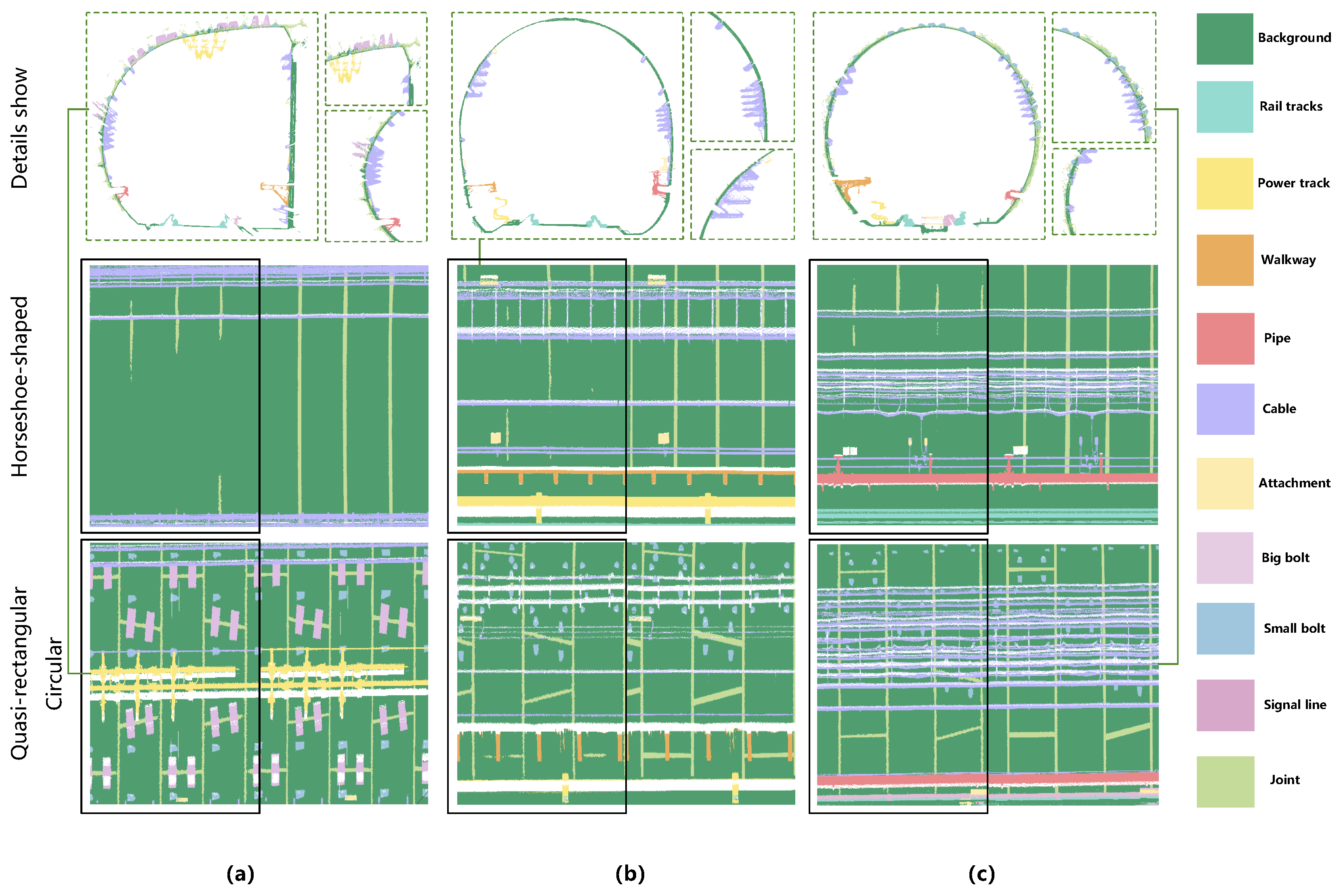

4.3. Results and Analysis

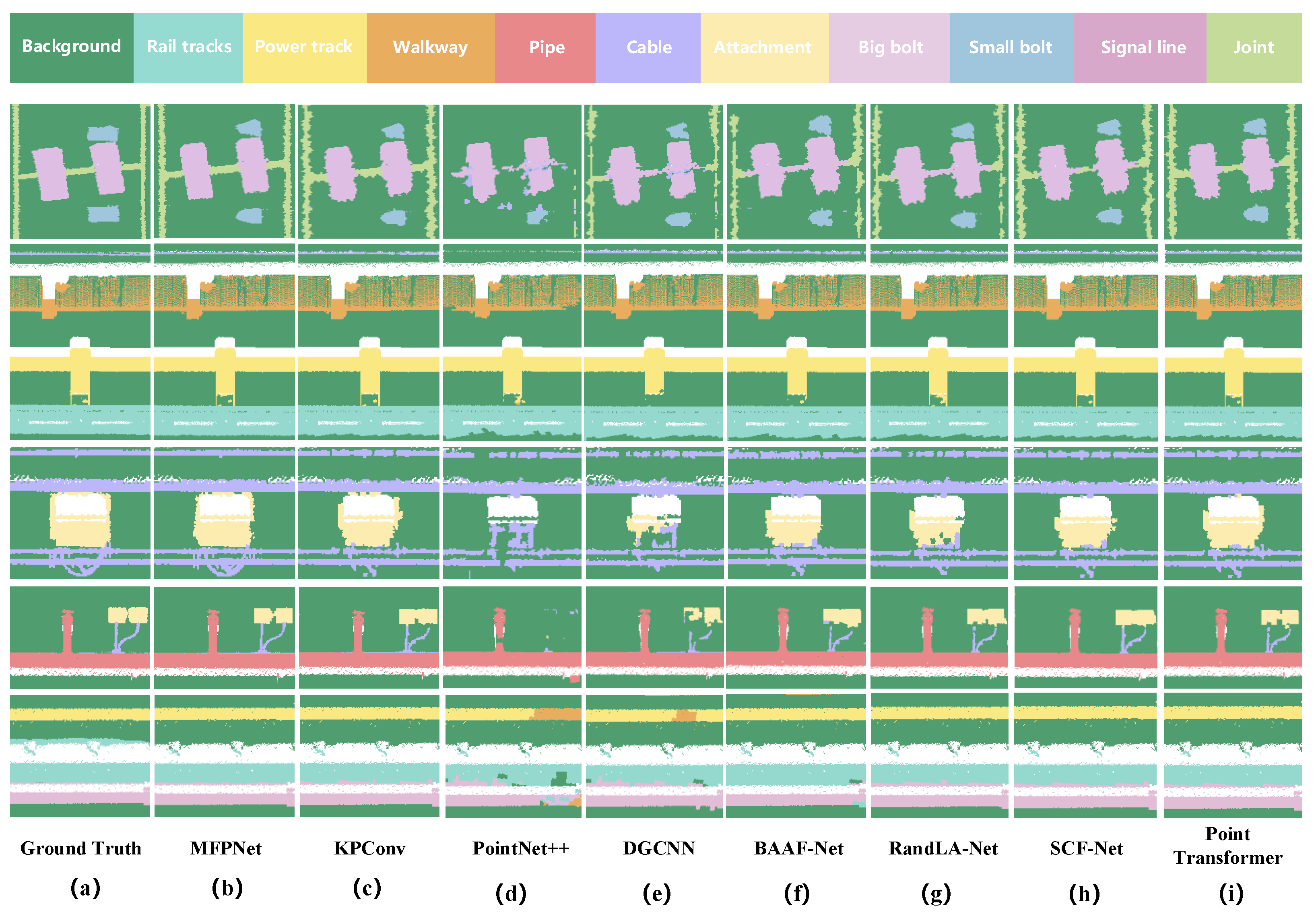

4.4. Comparative Experiment

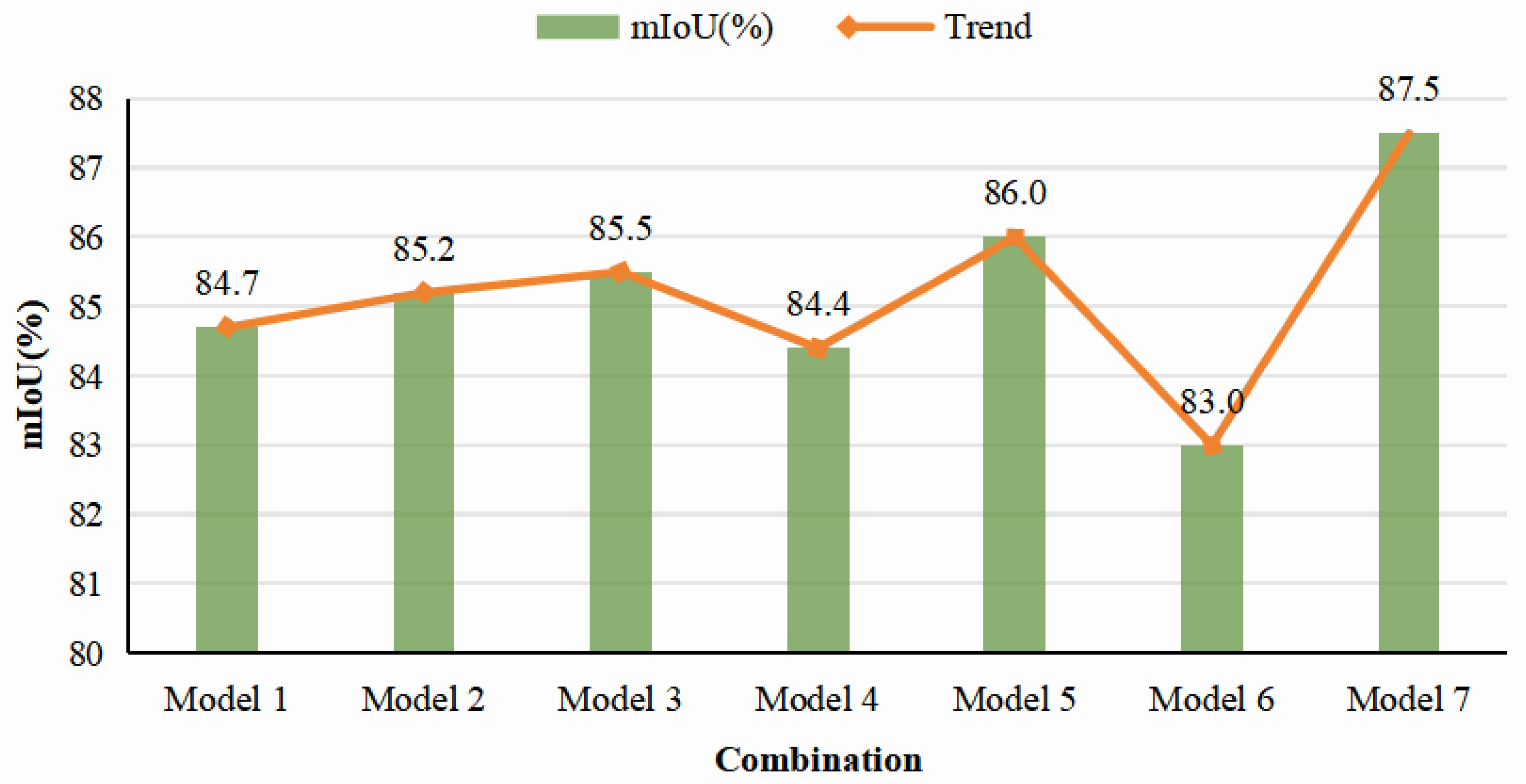

4.5. Ablation Experiment

5. Discussion

5.1. Joint Omission in Horseshoe-Shaped Tunnel Structures

5.2. Mis-Segmentation of Power Track as Cable in Quasi-Rectangular Tunnels

5.3. Analysis of Model Complexity and Engineering Practicality

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tan, L.; Hu, X.; Tang, T.; Yuan, D. A Lightweight Metro Tunnel Water Leakage Identification Algorithm via Machine Vision. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 150, 107327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Tan, L.; Xie, S.; Ma, B. Development and Applications of Common Utility Tunnels in China. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 76, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, K.; Zhang, G.; Sun, H. Construction Practice of Water Conveyance Tunnel among Complex Geotechnical Conditions: A Case Study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhan, K. Intelligent Mining Technology for an Underground Metal Mine Based on Unmanned Equipment. Engineering 2018, 4, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Zhao, J.W.; Zhou, H.W.; Ren, S.H.; Zhang, R.X. Secondary Utilizations and Perspectives of Mined Underground Space. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 96, 103129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, F.; Bai, Q. Underground Space Utilization of Coalmines in China: A Review of Underground Water Reservoir Construction. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 107, 103657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Togo, R.; Ogawa, T.; Haseyama, M. Defect Detection of Subway Tunnels Using Advanced U-Net Network. Sensors 2022, 22, 2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Liu, G.; Leng, B.; Ahmed, A.; Zhang, Z. Multispectral Water Leakage Detection Based on a One-Stage Anchor-Free Modality Fusion Network for Metro Tunnels. Autom. Constr. 2022, 140, 104345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Broere, W.; Cui, J. Metro Systems and Urban Development: Impacts and Implications. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 125, 104509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, H.; Xie, S.; Zou, J.; Ji, C.; Lu, Y.; Ren, X.; Wang, L. GL-Net: Semantic Segmentation for Point Clouds of Shield Tunnel via Global Feature Learning and Local Feature Discriminative Aggregation. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 199, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attard, L.; Debono, C.J.; Valentino, G.; Di Castro, M. Tunnel Inspection Using Photogrammetric Techniques and Image Processing: A Review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 144, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Taniguchi, T. Quantitative Condition Inspection and Assessment of Tunnel Lining. Autom. Constr. 2019, 102, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, L.M.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Park, Y.; Oh, C.; Nguyen, T.N.; Moon, H. Automatic Tunnel Lining Crack Evaluation and Measurement Using Deep Learning. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 124, 104472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xie, X.; Li, H.; Zhou, B.; Wang, Q.; Shahrour, I. Subway Tunnel Damage Detection Based on In-Service Train Dynamic Response, Variational Mode Decomposition, Convolutional Neural Networks and Long Short-Term Memory. Autom. Constr. 2022, 139, 104293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Sun, Y.; Xue, Y.; Wang, F. Inspection Equipment Study for Subway Tunnel Defects by Grey-Scale Image Processing. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2017, 32, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Li, Q.; Zhang, D. Deep Learning Based Image Recognition for Crack and Leakage Defects of Metro Shield Tunnel. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 77, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xie, Q.; Gong, X.; Yu, Z.; Xu, J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, J. Automatic Defect Detection of Metro Tunnel Surfaces Using a Vision-Based Inspection System. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2021, 47, 101206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, D.; Xie, Q.; Wu, Q.; Wang, J. Automatic Defect Detection and Segmentation of Tunnel Surface Using Modified Mask R-CNN. Measurement 2021, 178, 109316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yu, X.; Liu, S.; Chen, T.; Wang, W.; Jeon, G.; He, B. Tunnel SAM Adapter: Adapting Segment Anything Model for Tunnel Water Leakage Inspection. Geohazard Mech. 2024, 2, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Qiu, W.; Duan, D. Automatic Creation of As-Is Building Information Model from Single-Track Railway Tunnel Point Clouds. Autom. Constr. 2019, 106, 102911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, H.; Hu, Q.; Liu, H.; Liu, L.; Bennamoun, M. Deep Learning for 3D Point Clouds: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 4338–4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Z.; Chen, D.; Peethambaran, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xia, S.; Zhang, L. Tunnel Reconstruction with Block Level Precision by Combining Data-Driven Segmentation and Model-Driven Assembly. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 8853–8872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Ren, X.; Mao, Q.; Hu, Q.; Wang, W. Shield Subway Tunnel Deformation Detection Based on Mobile Laser Scanning. Autom. Constr. 2019, 106, 102889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Kim, M. Applications of 3D Point Cloud Data in the Construction Industry: A Fifteen-Year Review from 2004 to 2018. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2019, 39, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Vosselman, G.; Cao, Y.; Yang, M. LGENet: Local and Global Encoder Network for Semantic Segmentation of Airborne Laser Scanning Point Clouds. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.10192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Zhang, L.; Lin, X.; Gilani, S.Z.; Mian, A. Point Attention Network for Semantic Segmentation of 3D Point Clouds. Pattern Recognit. 2020, 107, 107446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Ji, A.; Zhang, L. Sewer Defect Detection from 3D Point Clouds Using a Transformer-Based Deep Learning Model. Autom. Constr. 2022, 136, 104163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, K.; Arashpour, M.; Asadi, E.; Masoumi, H.; Bai, Y.; Behnood, A. 3D Point Cloud Data Processing with Machine Learning for Construction and Infrastructure Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 51, 101501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, X.; Chen, Z.; Lu, Z. A Review of Deep Learning-Based Semantic Segmentation for Point Cloud. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 179118–179133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Xue, B.; Xu, Z.; Ruan, X.; Nie, P.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, Z. PointPPE: A Precise Recognition Method for Complex Machining Features Based on Point Cloud Analysis Network with Polynomial Positional Encoding. Displays 2026, 91, 103214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, A.; Chew, A.W.Z.; Xue, X.; Zhang, L. An Encoder–Decoder Deep Learning Method for Multi-Class Object Segmentation from 3D Tunnel Point Clouds. Autom. Constr. 2022, 137, 104187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Li, T.; Yang, Y.; Horng, S. Multivariate Time Series Forecasting via Attention-Based Encoder–Decoder Framework. Neurocomputing 2020, 388, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, A.W.Z.; Ji, A.; Zhang, L. Large-Scale 3D Point-Cloud Semantic Segmentation of Urban and Rural Scenes Using Data Volume Decomposition Coupled with Pipeline Parallelism. Autom. Constr. 2022, 133, 103995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ji, A.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, Q. Deep Learning for Large-Scale Point Cloud Segmentation in Tunnels Considering Causal Inference. Autom. Constr. 2023, 152, 104915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, X.; Hu, X.; Chen, F.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Tang, T. LCJ-Seg: Tunnel Lining Construction Joint Segmentation via Global Perception. In Proceedings of the IEEE 27th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Edmonton, AB, Canada, 24–27 September 2024; pp. 993–998. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, C.R.; Su, H.; Mo, K.; Guibas, L.J. PointNet: Deep Learning on Point Sets for 3D Classification and Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8099499 (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Qi, C.R.; Yi, L.; Su, H.; Guibas, L. PointNet++: Deep Hierarchical Feature Learning on Point Sets in a Metric Space. In Proceedings of the NIPS’17: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Q.; Yang, B.; Xie, L.; Rosa, S.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Trigoni, N.; Markham, A. RandLA-Net: Efficient Semantic Segmentation of Large-Scale Point Clouds. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11105–11114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Z.; Sarma, S.; Bronstein, M.; Solomon, J. Dynamic Graph CNN for Learning on Point Clouds. ACM Trans. Graph. 2019, 38, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Wang, B.; Gan, V.; Wang, M.; Cheng, J. Automated Semantic Segmentation of Industrial Point Clouds Using ResPointNet++. Autom. Constr. 2021, 130, 103874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, B. Point Cloud Semantic Segmentation Network Based on Graph Convolution and Attention Mechanism. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 141, 109790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, E.E.; Baci, S.; Cavdar, S. SalsaNet: Fast Road and Vehicle Segmentation in LiDAR Point Clouds for Autonomous Driving. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 19 October–13 November 2020; pp. 926–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Tian, S.; Lu, B.; Zhang, L.; Ning, X.; Bai, X. Deep Learning-Based 3D Point Cloud Classification: A Systematic Survey and Outlook. Displays 2023, 79, 102456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Cheng, L.; Wang, G.; Hu, M.; Yu, Z.; Du, M.; Ning, X. Fusing Differentiable Rendering and Language–Image Contrastive Learning for Superior Zero-Shot Point Cloud Classification. Displays 2024, 84, 102773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Dong, Z.; Yang, B. A Point-Based Deep Learning Network for Semantic Segmentation of MLS Point Clouds. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 175, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Li, J.; Mao, Q.; Hu, Q.; Dong, C.; Tao, Y. STSD: A Large-Scale Benchmark for Semantic Segmentation of Subway Tunnel Point Cloud. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 150, 105829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ji, A.; Wang, K.; Zhang, L. UnrollingNet: An Attention-Based Deep Learning Approach for the Segmentation of Large-Scale Point Clouds of Tunnels. Autom. Constr. 2022, 142, 104456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, H.; Qi, C.R.; Deschaud, J.-E.; Marcotegui, B.; Goulette, F.; Guibas, L. KPConv: Flexible and Deformable Convolution for Point Clouds. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.08889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, F.; Tan, Z. EB-LG Module for 3D Point Cloud Classification and Segmentation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Dong, Q.; Zhu, F.; Lv, Y.; Ye, P.; Wang, F.-Y. SCF-Net: Learning Spatial Contextual Features for Large-Scale Point Cloud Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Virtual, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 14499–14508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Anwar, S.; Barnes, N. Semantic Segmentation for Real Point Cloud Scenes via Bilateral Augmentation and Adaptive Fusion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Virtual, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 1757–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Jiang, L.; Jia, J.; Torr, P.H.S.; Koltun, V. Point Transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 16259–16268. [Google Scholar]

| Sets | Background | Rails Tracks | Power Track | Walkway | Pipe | Cable | Attachment | Big Bolt | Small Bolt | Signal Line | Joint |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision (%) | 98.5 | 95.4 | 99.3 | 97.9 | 98.9 | 93.6 | 90.9 | 93.2 | 83.6 | 90.9 | 61.3 |

| Recall (%) | 96.6 | 97.0 | 99.6 | 97.9 | 99.7 | 95.6 | 89.0 | 94.2 | 92.8 | 98.1 | 82.6 |

| F1 Score (%) | 97.5 | 96.2 | 99.4 | 97.9 | 99.3 | 94.6 | 89.9 | 93.7 | 87.9 | 94.4 | 70.4 |

| IoU (%) | 95.2 | 92.7 | 98.9 | 95.9 | 98.6 | 89.7 | 81.7 | 88.2 | 78.5 | 89.3 | 54.3 |

| Class | PointNet++ | DGCNN | SCF-Net | RandLA-Net | BAAF-Net | Point-Transformer | KPConv | MFP-Net |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background | 72.0 | 74.0 | 82.3 | 80.3 | 80.5 | 81.0 | 93.6 | 95.2 |

| Rails tracks | 60.0 | 66.0 | 88.5 | 87.3 | 87.2 | 90.0 | 91.0 | 92.7 |

| Power track | 59.0 | 65.0 | 93.6 | 92.5 | 92.8 | 92.5 | 96.6 | 98.9 |

| Walkway | 68.5 | 73.0 | 84.6 | 84.5 | 83.0 | 85.0 | 94.3 | 95.9 |

| Pipe | 68.0 | 72.0 | 87.5 | 86.9 | 87.0 | 88.0 | 97.4 | 98.6 |

| Cable | 55.0 | 58.0 | 82.2 | 80.2 | 80.8 | 83.0 | 85.4 | 89.7 |

| Attachment | 36.7 | 48.0 | 62.0 | 53.9 | 57.1 | 69.0 | 76.6 | 81.7 |

| Big Bolt | 52.2 | 60.0 | 76.3 | 79.5 | 79.5 | 81.0 | 84.4 | 88.2 |

| Small bolt | 35.9 | 52.0 | 59.7 | 57.9 | 57.9 | 70.0 | 68.8 | 78.5 |

| Signal line | 62.0 | 70.0 | 77.7 | 75.0 | 76.3 | 78.5 | 84.0 | 89.3 |

| Joint | 26.5 | 32.0 | 37.6 | 34.7 | 34.6 | 38.0 | 34.3 | 54.3 |

| mIoU(%) | 54.5 | 61.8 | 75.6 | 73.9 | 74.2 | 77.8 | 82.4 | 87.5 |

| Module | Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Multi-Scale KPConv | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| EFFM | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| FMEM | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| mIoU (%) | 84.7 | 85.2 | 85.5 | 84.4 | 86.0 | 83.0 | 87.5 |

| Accuracy (%) | 93.7 | 94.1 | 84.8 | 93.5 | 95.4 | 93.0 | 96.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tong, J.; Ji, M.; Song, P.; Chen, Q.; Chen, C. MFPNet: A Semantic Segmentation Network for Regular Tunnel Point Clouds Based on Multi-Scale Feature Perception. Sensors 2026, 26, 848. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030848

Tong J, Ji M, Song P, Chen Q, Chen C. MFPNet: A Semantic Segmentation Network for Regular Tunnel Point Clouds Based on Multi-Scale Feature Perception. Sensors. 2026; 26(3):848. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030848

Chicago/Turabian StyleTong, Junwei, Min Ji, Pengfei Song, Qiang Chen, and Chun Chen. 2026. "MFPNet: A Semantic Segmentation Network for Regular Tunnel Point Clouds Based on Multi-Scale Feature Perception" Sensors 26, no. 3: 848. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030848

APA StyleTong, J., Ji, M., Song, P., Chen, Q., & Chen, C. (2026). MFPNet: A Semantic Segmentation Network for Regular Tunnel Point Clouds Based on Multi-Scale Feature Perception. Sensors, 26(3), 848. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030848