Image Quality Standardization in Radiomics: A Systematic Review of Artifacts, Variability, and Feature Stability

Abstract

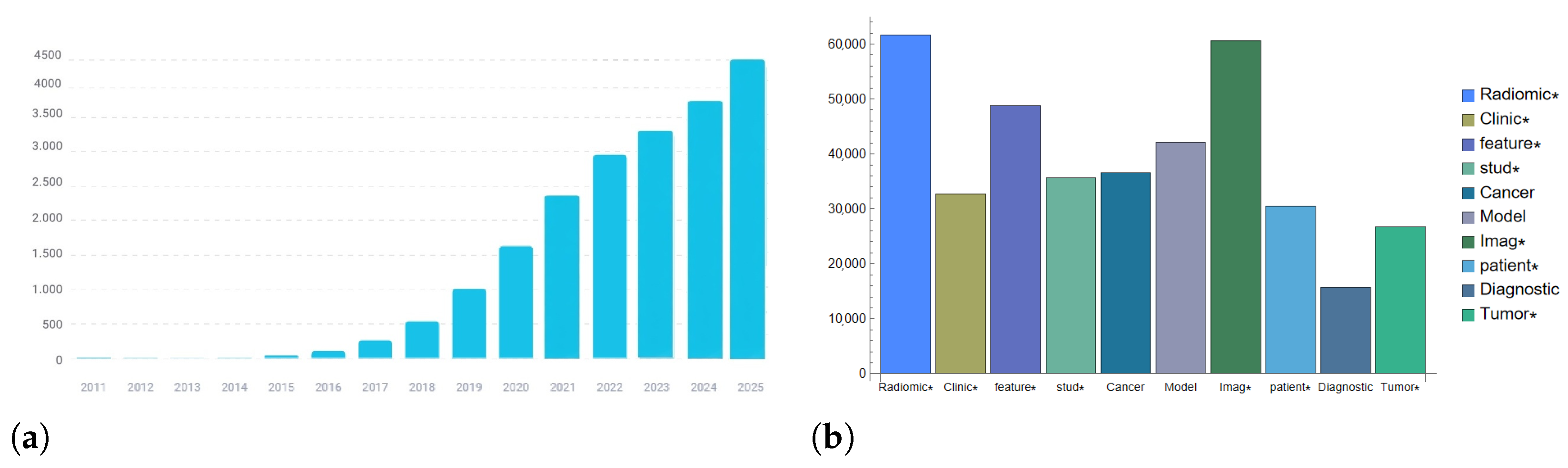

1. Introduction

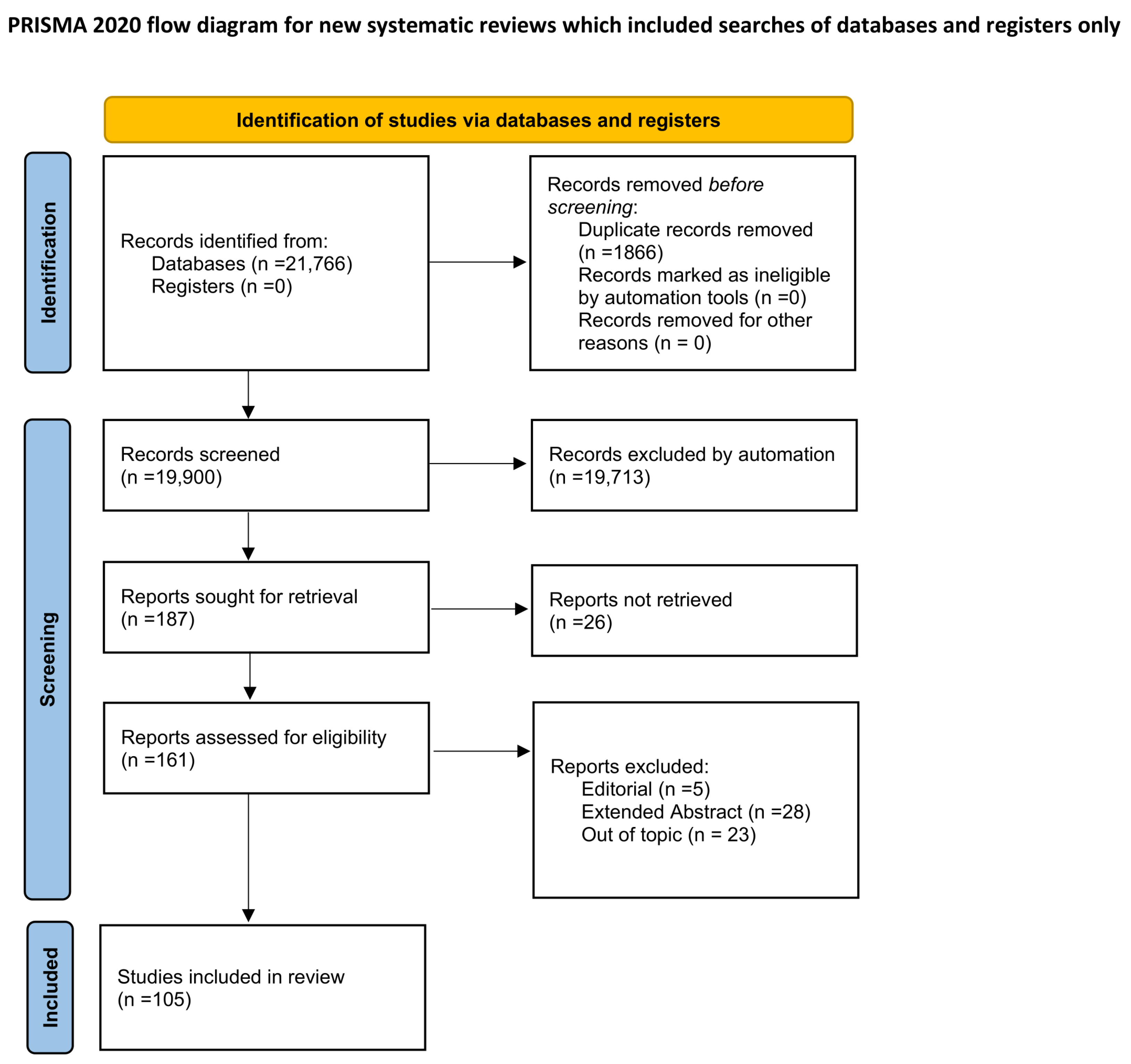

2. Materials and Methods

- Scopus:TITLE-ABS-KEY (radiomics) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY (noise)OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (artifact)OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (blur) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“image perturbation”)OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“image quality metrics”))

- PubMed:(Radiomics) AND ((Noise) OR (Blur) OR (artifact)OR (“image perturbation”) OR (“image quality metrics”))

- IEEE Xplore:((“Document Title”:“radiomics”) OR (“Abstract”:“radiomics”))AND (“noise” OR “blur” OR “artifact” OR “image perturbation”OR “image quality metrics”)

- Population: Imaging studies (CT, MRI, PET, or hybrid modalities) employing radiomic feature extraction.

- Intervention/Exposure: Image quality variations or artifacts, whether simulated, measured, or induced experimentally (e.g., noise, blur, motion, beam hardening, or acquisition parameters).

- Comparator: Reference or baseline imaging conditions, or different levels of degradation.

- Outcome: Quantitative assessment of feature variability, robustness, or reproducibility in relation to IQA metrics.

3. Methodological and Scope Limitations

4. Radiomics and Image Quality

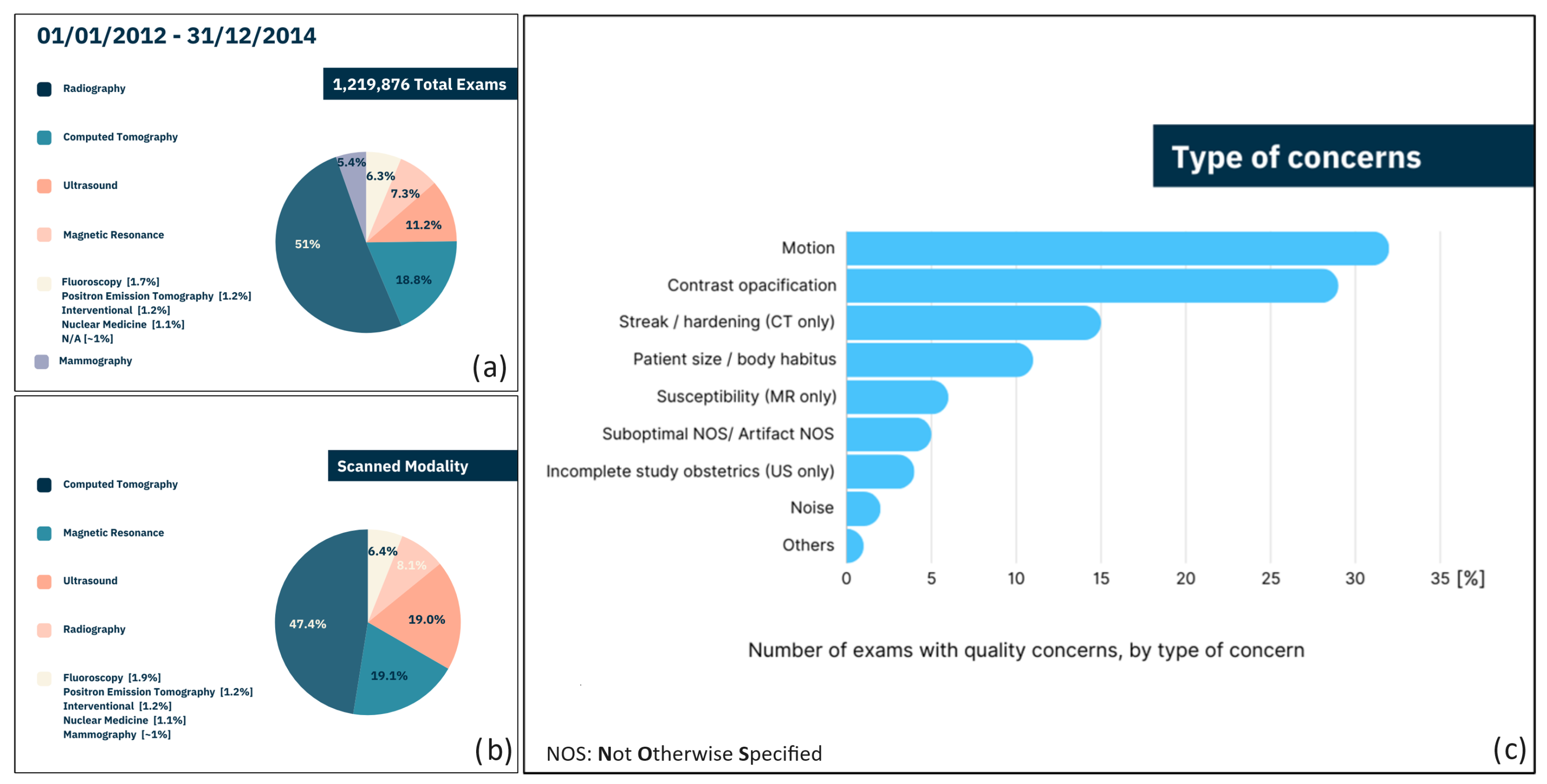

5. Image Quality Assessment Tools: A Need

- In 2.4% of cases, operators who assessed the images asserted the importance of highlighting defects potentially leading to data misinterpretation. However, it is impossible to determine the number of examiners who did not identify potential defects.

- Reporting of defects may have been omitted by experienced operators relying on their personal expertise.

- Reporting of defects may have been omitted by less experienced operators who were unable to recognize the problem.

- Although 2.4% may appear to be a small percentage, it is important to emphasize that this percentage, within a sample of over 1,200,000 cases, translates to approximately 30,000 potential misdiagnoses, with all the associated consequences.

- If only Positron Emission Tomography (PET), CT, and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) are considered, the percentage of defects potentially leading to data misinterpretation highlighted by the operators increases up to 6%. This means that these last techniques, typically adopted for automatic cancer detection, are more prone to being affected by alterations during acquisition.

6. Main Concerns in Clinical Practice

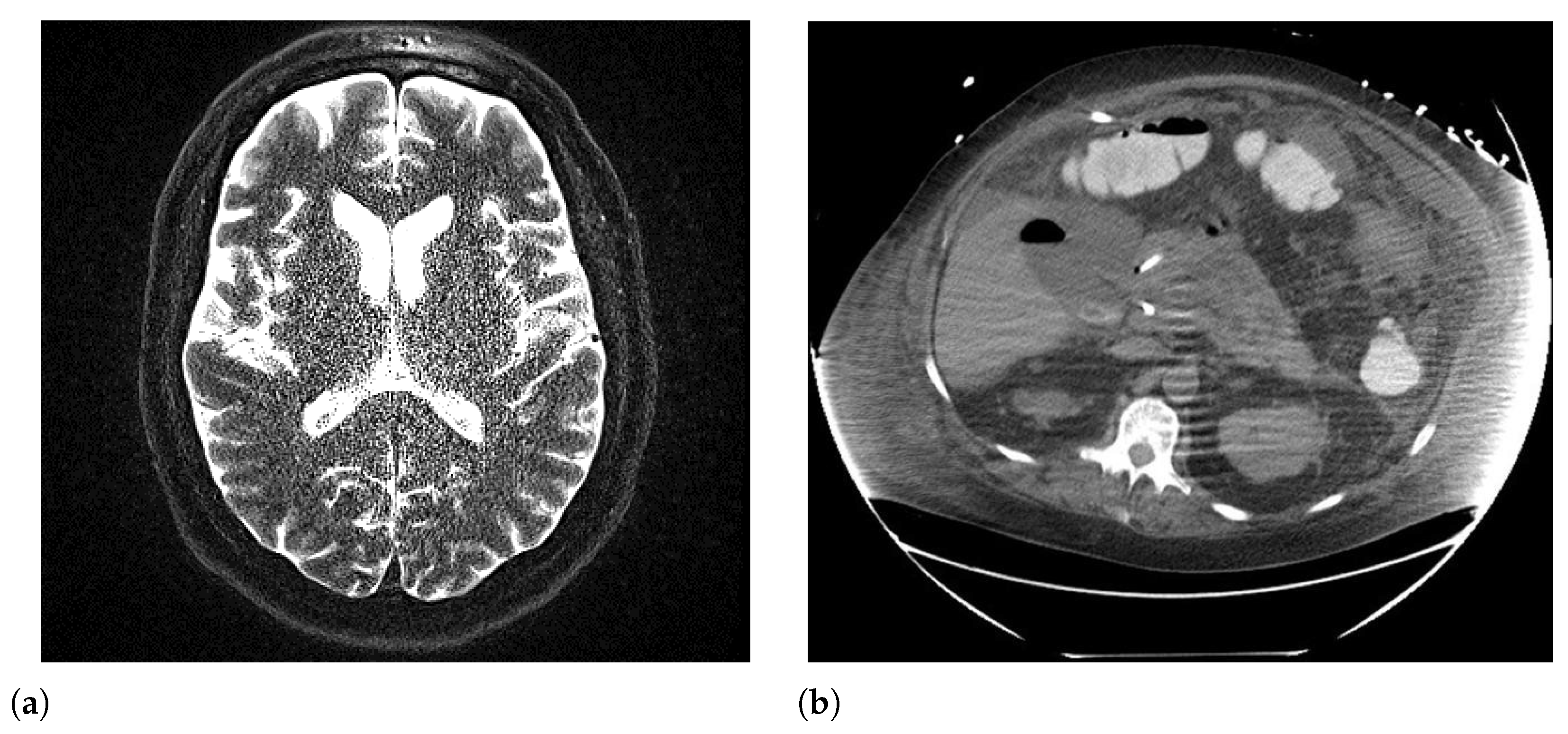

6.1. Motion

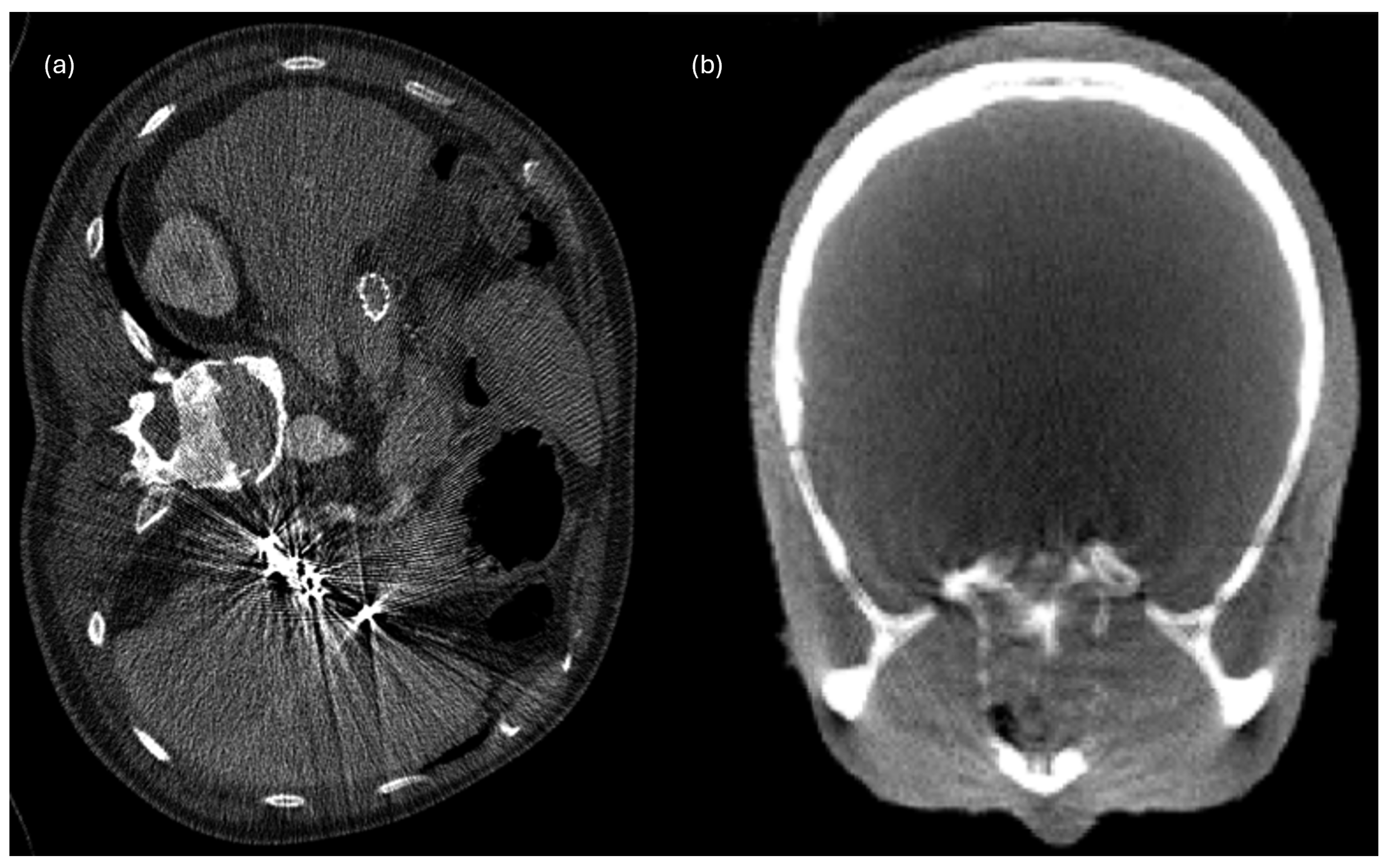

6.2. Beam Hardening Streaks and Cupping Artifacts

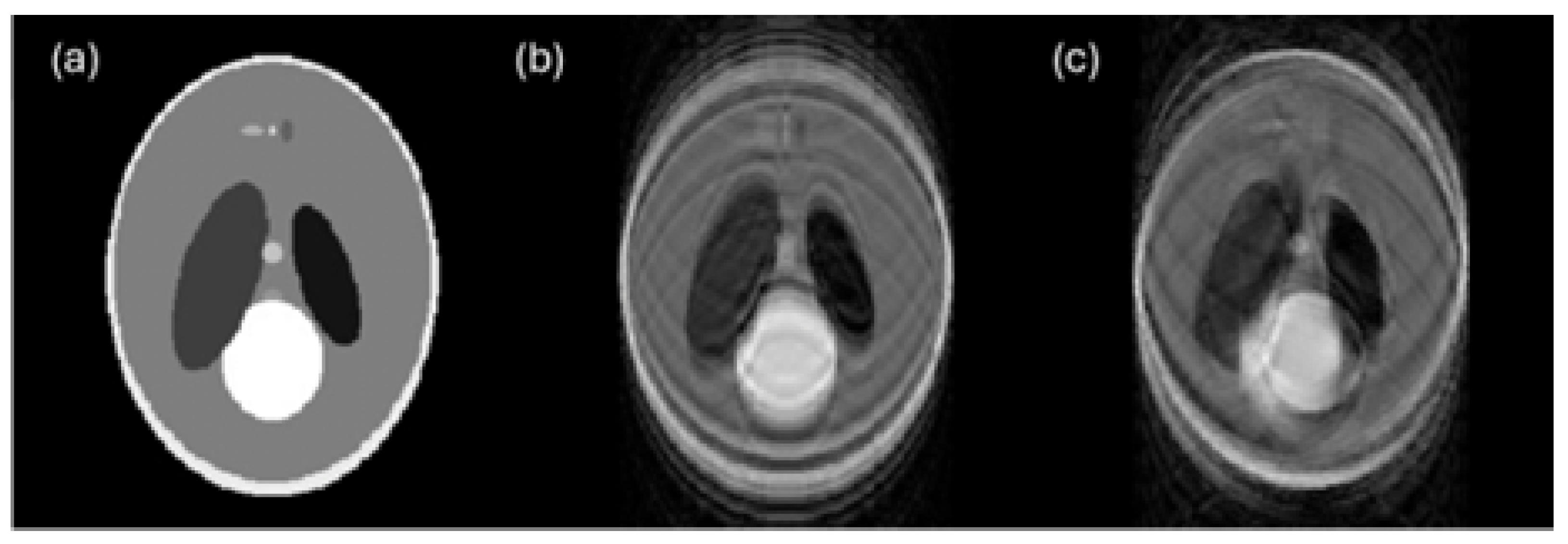

6.3. Noise

6.4. Blur

6.5. Body Habitus/Patient Size

7. The Impact of Image Quality on Segmentation

8. Image Quality Improves Radiomic Biomarker Extraction

9. Image Quality Metrics

Full-Reference vs. No-Reference Metrics

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IQA | Image Quality Assessment |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| VAE | Variational Autoencoder |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| CNR | Contrast-to-Noise Ratio |

| SSIM | Structural Similarity Index |

| LPIPS | Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity |

| BRISQUE | Blind/Referenceless Image Spatial Quality Evaluator |

| IBSI | Image Biomarker Standardization Initiative |

| TRIPOD | Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for |

| Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis | |

| CLAIM | Checklist for Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging |

| ALARA | As Low As Reasonably Achievable |

| FR | Full-Reference |

| NR | No-Reference |

| ICC | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| GLCM | Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix |

| GLRLM | Gray-Level Run-Length Matrix |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| QUADAS-2 | Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies, 2nd edition |

| GRADE | Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation |

References

- Yip, S.S.; Aerts, H.J. Applications and limitations of radiomics. Phys. Med. Biol. 2016, 61, R150–R166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, F.; Agostini, A.; Borgheresi, A.; Marchegiani, M.; Zannotti, A.; Giacomelli, G.; Pierpaoli, L.; Tola, E.; Galiffa, E.; Giovagnoni, A. Insights into radiomics: A comprehensive review for beginners. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2025, 27, 4091–4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avanzo, M.; Stancanello, J.; El Naqa, I. Beyond imaging: The promise of radiomics. Phys. Medica 2017, 38, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCague, C.; Ramlee, S.; Reinius, M.; Selby, I.; Hulse, D.; Piyatissa, P.; Bura, V.; Crispin-Ortuzar, M.; Sala, E.; Woitek, R. Introduction to radiomics for a clinical audience. Clin. Radiol. 2023, 78, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shur, J.D.; Doran, S.J.; Kumar, S.; ap Dafydd, D.; Downey, K.; O’Connor, J.P.B.; Papanikolaou, N.; Messiou, C.; Koh, D.-M.; Orton, M.R. Radiomics in Oncology: A Practical Guide. RadioGraphics 2021, 41, 1717–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.E.; Kim, D.; Kim, H.S.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Cho, S.J.; Shin, J.H.; Kim, J.H. Quality of science and reporting of radiomics in oncologic studies: Room for improvement according to radiomics quality score and TRIPOD statement. Eur. Radiol. 2020, 30, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fass, L. Imaging and cancer: A review. Mol. Oncol. 2008, 2, 115–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Giger, M.L.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, W.; Horsch, K.; Lan, L.; Jamieson, A.R.; Sennett, C.A.; Jansen, S.A. Evaluation of Computer-Aided Diagnosis on a Large Clinical Full-Field Digital Mammographic Dataset. Acad. Radiol. 2008, 15, 1437–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Naqa, I.; Grigsby, P.; Apte, A.; Kidd, E.; Donnelly, E.; Khullar, D.; Chaudhari, S.; Yang, D.; Schmitt, M.; Laforest, R.; et al. Exploring feature-based approaches in PET images for predicting cancer treatment outcomes. Pattern Recognit. 2009, 42, 1162–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Gu, Y.; Basu, S.; Berglund, A.; Eschrich, S.A.; Schabath, M.B.; Forster, K.; Aerts, H.J.W.L.; Dekker, A.; Fenstermacher, D.; et al. Radiomics: The process and the challenges. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2012, 30, 1234–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Timmeren, J.; Cester, D.; Tanadini-Lang, S.; Alkadhi, H.; Baessler, B. Radiomics in medical imaging—“how-to” guide and critical reflection. Insights Imaging 2020, 11, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Tan, Y.; Tsai, W.Y.; Qi, J.; Xie, C.; Lu, L.; Schwartz, L.H. Reproducibility of radiomics for deciphering tumor phenotype with imaging. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Yin, F.F. Impact of image quality on radiomics applications. Phys. Med. Biol. 2022, 67, 15TR03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traverso, A.; Wee, L.; Dekker, A.; Gillies, R. Repeatability and Reproducibility of Radiomic Features: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2018, 102, 1143–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, R.J.; Kinahan, P.E.; Hricak, H. Radiomics: Images Are More than Pictures, They Are Data. Radiology 2016, 278, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvie, S.; Mazzoni, L.N.; O’Doherty, J. A review on the use of imaging biomarkers in oncology clinical trials: Quality assurance strategies for technical validation. Tomography 2023, 9, 1876–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanshahi, A.; Soleymani, Y.; Fazel Ghaziani, M.; Khezerloo, D. Radiomics reproducibility challenge in computed tomography imaging as a nuisance to clinical generalization: A mini-review. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 2023, 54, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwanenburg, A.; Vallières, M.; Abdalah, M.A.; Aerts, H.J.W.L.; Andrearczyk, V.; Apte, A.; Ashrafinia, S.; Bakas, S.; Beukinga, R.J.; Boellaard, R.; et al. The Image Biomarker Standardization Initiative: Standardized Quantitative Radiomics for High-Throughput Image-based Phenotyping. Radiology 2020, 295, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, D.; Wu, G.; Suk, H.-I. Deep learning in medical image analysis. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 19, 221–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B. Understanding sources of variation to improve the reproducibility of radiomics. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 633176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aerts, H.J.W.L.; Velazquez, E.R.; Leijenaar, R.T.H.; Parmar, C.; Grossmann, P.; Carvalho, S.; Bussink, J.; Monshouwer, R.; Haibe-Kains, B.; Rietveld, D.; et al. Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depeursinge, A.; Andréarczyk, V.; Whybra, P.; van Griethuysen, J.J.; Müller, H.; Schaer, R.; Vallières, M.; Zwanenburg, A. Standardised convolutional filtering for radiomics. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.05470. [Google Scholar]

- Pfaehler, E.; Zhovannik, I.; Wei, L.; Boellaard, R.; Dekker, A.; Monshouwer, R.; El Naqa, I.; Bussink, J.; Gillies, R.; Wee, L.; et al. A systematic review and quality of reporting checklist for repeatability and reproducibility of radiomic features. Phys. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 2021, 20, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Walia, E.; Babyn, P. Generative Adversarial Network in Medical Imaging: A Review. Med. Image Anal. 2019, 58, 101552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, H.; Xie, G.; Zhang, Y. Image Denoising Using an Improved Generative Adversarial Network with Wasserstein Distance. In Proceedings of the 2021 40th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Shanghai, China, 26–28 July 2021; pp. 7027–7032. [Google Scholar]

- Wolterink, J.M.; Leiner, T.; Viergever, M.A.; Išgum, I. Generative Adversarial Networks for Noise Reduction in Low-Dose CT. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2017, 36, 2536–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalare, K.; Bajpai, M.; Sarkar, S.; Dubey, S.R. Deep neural network for beam hardening artifacts removal in image reconstruction. Appl. Intell. 2022, 52, 6037–6056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mali, S.A.; Ibrahim, A.; Woodruff, H.C.; Andrearczyk, V.; Müller, H.; Primakov, S.; Salahuddin, Z.; Chatterjee, A.; Lambin, P. Making Radiomics More Reproducible across Scanner and Imaging Protocol Variations: A Review of Harmonization Methods. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kállos-Balogh, Z.; Egri, Á.; Sera, A.; Horváth, I.K.; Trencsényi, E.; Garai, I. Multicentric study on the reproducibility and robustness of PET-based radiomics features with a realistic activity painting phantom. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0309540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvat, N.; Papanikolaou, N.; Koh, D.-M. Radiomics Beyond the Hype: A Critical Evaluation Toward Oncologic Clinical Use. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2024, 6, e230437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiavo, J.H. PROSPERO: An International Register of Systematic Review Protocols. Med. Ref. Serv. Q. 2019, 38, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiting, P.F.; Rutjes, A.W.; Westwood, M.E.; Mallett, S.; Deeks, J.J.; Reitsma, J.B.; Leeflang, M.M.; Sterne, J.A.; Bossuyt, P.M. QUADAS-2: A revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minozzi, S.; Cinquini, M.; Arienti, C.; Battain, P.C.; Brigadoi, G.; Del Vicario, M.; Di Domenico, G.; Farma, T.; Federico, S.; Innocenti, T.; et al. Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation and Confidence in Network Meta-Analysis showed moderate to substantial concordance in the evaluation of certainty of the evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2025, 184, 111811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambin, P.; Rios-Velazquez, E.; Leijenaar, R.T.H.; Carvalho, S.; van Stiphout, R.G.P.M.; Granton, P.; Zegers, C.M.L.; Gillies, R.J.; Boellard, R.; Dekker, A.; et al. Radiomics: Extracting more information from medical images using advanced feature analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammirato, S.; Felicetti, A.M.; Rogano, D.; Linzalone, R.; Corvello, V. Digitalising the Systematic Literature Review process: The MySLR platform. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2022, 21, 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabotuwana, T.; Bhandarkar, V.S.; Hall, C.S.; Gunn, M.L. Detecting Technical Image Quality in Radiology Reports. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2018, 2018, 780–788. [Google Scholar]

- Krupa, K.; Bekiesińska-Figatowska, M. Artifacts in magnetic resonance imaging. Pol. J. Radiol. 2015, 80, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, T.B.; Nayak, K.S. MRI artifacts and correction strategies. Imaging Med. 2010, 2, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budrys, T.; Veikutis, V.; Lukosevicius, S.; Gleizniene, R.; Monastyreckiene, E.; Kulakiene, I. Artifacts in magnetic resonance imaging: How it can really affect diagnostic image quality and confuse clinical diagnosis? J. Vibroengineering 2018, 20, 1202–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Wong, K.P.; Wardak, M.; Dahlbom, M.; Kepe, V.; Barrio, J.R.; Nelson, L.D.; Small, G.W.; Huang, S.C. Automated movement correction for dynamic PET/CT images: Evaluation with phantom and patient data. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommer, K.; Saalbach, A.; Brosch, T.; Hall, C.; Cross, N.M.; Andre, J.B. Correction of Motion Artifacts Using a Multiscale Fully Convolutional Neural Network. AJNR. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2020, 41, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebbian, M.R.; Walia, E.; Wahid, K.A. Which K-Space Sampling Schemes is good for Motion Artifact Detection in Magnetic Resonance Imaging? arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.08516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Ackerman, J.L.; Petibon, Y.; Brady, T.J.; El Fakhri, G.; Ouyang, J. MR-based motion correction for PET imaging using wired active MR microcoils in simultaneous PET-MR: Phantom study. Med. Phys. 2014, 41, 041910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev, M.; Maclaren, J.; Herbst, M. Motion artifacts in MRI: A complex problem with many partial solutions. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2015, 42, 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küstner, T.; Armanious, K.; Yang, J.; Yang, B.; Schick, F.; Gatidis, S. Retrospective correction of motion-affected MR images using deep learning frameworks. Magn. Reson. Med. 2019, 82, 1527–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadah, Y.M. Motion artifact suppression in MRI using registration of segmented acquisitions. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2007, 54, 673–688. [Google Scholar]

- Pessis, E.; Campagna, R.; Sverzut, J.-M.; Bach, F.; Rodallec, M.; Guerini, H.; Feydy, A.; Drapé, J.-L. Virtual monochromatic spectral imaging with fast kilovoltage switching: Reduction of metal artifacts at CT. Radiographics 2013, 33, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revision Radiology. Revision Radiology—Radiology Education Resources. Available online: http://www.revisionrads.com/ (accessed on 30 January 2026).

- Xie, S.; Li, C.; Li, H.; Ge, Q. A level set method for cupping artifact correction in cone-beam CT. Med. Phys. 2015, 42, 4888–4895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Man, B.; Nuyts, J.; Dupont, P.; Marchal, G.; Suetens, P. Reduction of metal streak artifacts in X-ray computed tomography using a transmission maximum a posteriori algorithm. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2000, 47, 977–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Leng, S.; McCollough, C.H. Dual-energy CT-based monochromatic imaging. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2012, 199, S9–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stowe, J. Suppression of the CT beam hardening streak artifact using predictive correction on detector data. Univers. J. Med. Sci. 2016, 4, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, H. Convolutional neural network based metal artifact reduction in X-ray computed tomography. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2018, 37, 1370–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackin, D.; Fave, X.; Zhang, L.; Fried, D.; Yang, J.; Taylor, B.; Rodriguez-Rivera, E.; Dodge, C.; Jones, A.K.; Court, L. Measuring Computed Tomography Scanner Variability of Radiomics Features. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2015, 39, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.; Ronald, J.; Vernuccio, F.; Nelson, R.C.; Ramirez-Giraldo, J.C.; Solomon, J.; Patel, B.N.; Samei, E.; Marin, D. Reproducibility of CT Radiomic Features within the Same Patient: Influence of Radiation Dose and CT Reconstruction Settings. Radiology 2020, 294, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, J.P.B.; Aboagye, E.; Adams, J.E.; Aerts, H.J.W.L.; Barrington, S.F.; Beer, A.J.; Boellaard, R.; Bohndiek, S.E.; Brady, M.; Brown, G.; et al. Imaging biomarker roadmap for cancer studies. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiri, I.; Rahmim, A.; Ghaffarian, P.; Geramifar, P.; Abdollahi, H.; Bitarafan-Rajabi, A. The impact of image reconstruction settings on 18F-FDG PET radiomic features: Multi-scanner phantom and patient studies. Eur. Radiol. 2020, 30, 4498–4509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umehara, K.; Ota, J.; Ishida, T. Application of super-resolution convolutional neural network for enhancing image resolution in chest CT. J. Digit. Imaging 2018, 31, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Hu, Y.-C.; Liu, C.; Halpenny, D.; Hellmann, M.D.; Deasy, J.O.; Mageras, G.; Veeraraghavan, H. Multiple resolution residually connected feature streams for automatic lung tumor segmentation from CT images. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2021, 40, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juntu, J.; Sijbers, J.; Van Dyck, D.; Gielen, J. Machine learning study of several classifiers trained with texture analysis features to differentiate benign from malignant soft-tissue tumors in T1-MRI images. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2010, 31, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, L.L.; Schoepf, U.J.; Meinel, F.G.; Nance, J.W., Jr.; Bastarrika, G.; Leipsic, J.A.; Paul, N.S.; Rengo, M.; Laghi, A.; De Cecco, C.N. State of the art: Iterative CT reconstruction techniques. Radiology 2015, 276, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misko, O.; Veseliak, V. Singular Value Decomposition in Image Noise Filtering; Ukrainian Catholic University: Lviv, Ukraine, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Uppot, R.N. Technical Challenges of Imaging and Image-Guided Interventions in Obese Patients. Br. J. Radiol. 2018, 91, 20170931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumakov, D.; Kayumov, Z.; Zhumaniezov, A.; Chikrin, D.; Galimyanov, D. Elimination of Defects in Mammograms Caused by a Malfunction of the Device Matrix. J. Imaging 2022, 8, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gang, G.J.; Deshpande, R.; Stayman, J.W. Standardization of Histogram- and Gray-Level Co-Occurrence Matrices-Based Radiomics in the Presence of Blur and Noise. Phys. Med. Biol. 2021, 66, 074004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.H.; Yun, C.S.; Kim, K.; Lee, Y.; Alzheimer Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Image Restoration Algorithm Incorporating Methods to Remove Noise and Blurring from Positron Emission Tomography Imaging for Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis. Phys. Medica 2022, 103, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmane, I.; Gampp, C.; Hausmann, D.; Mavridis, S.; Euler, A.; Hefermehl, L.J.; Knoth, F.; Kubik-Huch, R.A.; Nocito, A.; Niemann, T. Evaluation of image quality of overweight and obese patients in CT using high data rate detectors. In Vivo 2023, 37, 1186–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindera, S.T.; Nelson, R.C.; Toth, T.L.; Nguyen, G.T.; Toncheva, G.I.; DeLong, D.M.; Yoshizumi, T.T. Effect of patient size on radiation dose for abdominal MDCT with automatic tube current modulation: Phantom study. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2008, 190, W100–W105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.J.; Goldsmith, Z.G.; Wang, C.; Nguyen, G.; Astroza, G.M.; Neisius, A.; Iqbal, M.W.; Neville, A.M.; Lowry, C.; Toncheva, G.; et al. Obesity triples the radiation dose of stone protocol computerized tomography. J. Urol. 2013, 189, 2142–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginde, A.A.; Foianini, A.; Renner, D.M.; Valley, M.; Camargo, C.A., Jr. The challenge of CT and MRI imaging of obese individuals who present to the emergency department: A national survey. Obesity 2008, 16, 2549–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, G.; Robinson, J.; Punch, A.; Jimenez, Y.; Lewis, S. Understanding radiographic decision-making when imaging obese patients: A Think-Aloud study. J. Med. Radiat. Sci. 2022, 69, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppot, R.N.; Sahani, D.V.; Hahn, P.F.; Kalra, M.K.; Saini, S.S.; Mueller, P.R. Effect of obesity on image quality: Fifteen-year longitudinal study for evaluation of dictated radiology reports. Radiology 2006, 240, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, J.D.; Forsythe, A.V.; Brady, Z.; Butler, M.W.; Goergen, S.K.; Byrnes, G.B.; Giles, G.G.; Wallace, A.B.; Anderson, P.R.; Guiver, T.A.; et al. Cancer risk in 680,000 people exposed to computed tomography scans in childhood or adolescence: Data linkage study of 11 million Australians. BMJ 2013, 346, f2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israel, G.M.; Cicchiello, L.; Brink, J.; Huda, W. Patient Size and Radiation Exposure in Thoracic, Pelvic, and Abdominal CT Examinations Performed with Automatic Exposure Control. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2010, 195, 1340–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pednekar, G.V.; Udupa, J.K.; McLaughlin, D.J.; Wu, X.; Tong, Y.; Simone, C.B.; Camaratta, J.; Torigian, D.A. Image Quality and Segmentation. Proc. SPIE—Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 2018, 10576, 105762N. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Soewondo, W.; Haji, S.O.; Eftekharian, M.; Marhoon, H.A.; Dorofeev, A.E.; Jalil, A.T.; Jawad, M.A.; Jabbar, A.H. Noise reduction and mammography image segmentation optimization with novel QIMFT-SSA method. Comput. Opt. 2022, 46, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, B.; Yüzkan, S.; Mutlu, S.; Karagülle, M.; Kala, A.; Kadıoğlu, M. Influence of image preprocessing on the segmentation-based reproducibility of radiomic features: In vivo experiments on discretization and resampling parameters. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 2024, 30, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluim, J.P.W.; Maintz, J.B.A.; Viergever, M.A. Mutual-information-based registration of medical images: A survey. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2003, 22, 986–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- deSouza, N.M.; van der Lugt, A.; Deroose, C.M.; Alberich-Bayarri, A.; Bidaut, L.; Fournier, L.; Costaridou, L.; Oprea-Lager, D.E.; Kotter, E.; Smits, M.; et al. Standardised lesion segmentation for imaging biomarker quantitation: A consensus recommendation from ESR and EORTC. Insights Imaging 2022, 13, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chupetlovska, K.; Akinci D’Antonoli, T.; Bodalal, Z.; Abdelatty, M.A.; Erenstein, H.; Santinha, J.; Huisman, M.; Visser, J.J.; Trebeschi, S.; Lipman, G. ESR Essentials: A step-by-step guide of segmentation for radiologists—practice recommendations by the European Society of Medical Imaging Informatics. Eur. Radiol. 2025, 35, 6894–6904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Nadeem, M.; Abrar, M.; Amin, F.; Salam, A.; Khan, S. Enhancing Brain Tumor Segmentation Accuracy through Scalable Federated Learning with Advanced Data Privacy and Security Measures. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Whitehead, T.D.; Quirk, J.D.; Salter, A.; Ademuyiwa, F.O.; Li, S.; An, H.; Shoghi, K.I. Optimal co-clinical radiomics: Sensitivity of radiomic features to tumour volume, image noise and resolution in co-clinical T1-weighted and T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. eBioMedicine 2020, 59, 102963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Balestrieri, E.; Daponte, P.; Imperatore, R.; Lamonaca, F.; Paolucci, M.; Picariello, F. Morphometric measurement of fish blood cell: An image processing and ellipse fitting technique. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 5011712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccarelli, M.; Speranza, A.; Grimaldi, D.; Lamonaca, F. Automatic detection and surface measurements of micronucleus by a computer vision approach. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2010, 59, 2383–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M.; Menéndez Fernández-Miranda, P.; Bastarrika, G.; Iglesias, L.L. Enhancing radiomics and Deep Learning systems through the standardization of medical imaging workflows. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soliman, M.A.S.; Kelahan, L.C.; Magnetta, M.; Savas, H.; Agrawal, R.; Avery, R.J.; Aouad, P.; Liu, B.; Xue, Y.; Chae, Y.K.; et al. A Framework for Harmonization of Radiomics Data for Multicenter Studies and Clinical Trials. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2022, 6, e2200023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trojani, V.; Bassi, M.C.; Verzellesi, L.; Bertolini, M. Impact of Preprocessing Parameters in Medical Imaging-Based Radiomic Studies: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, G.S.; Reitsma, J.B.; Altman, D.G.; Moons, K.G. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): The TRIPOD statement. BMJ 2015, 350, g7594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongan, J.; Moy, L.; Kahn, C.E., Jr. Checklist for Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging (CLAIM): A guide for authors and reviewers. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2020, 2, e200029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larue, R.T.H.M.; van Timmeren, J.E.; de Jong, E.E.C.; Feliciani, G.; Leijenaar, R.T.H.; Schreurs, W.M.J.; Sosef, M.N.; Raat, F.H.P.J.; van der Zande, F.H.R.; Das, M.; et al. Influence of gray level discretization on radiomic feature stability for different CT scanners, tube currents and slice thicknesses: A comprehensive phantom study. Acta Oncol. 2017, 56, 1544–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Turangan, A.; Han, H.; Lei, X.; Hwang, D.H.; Cen, S.; Levy, J.; Jensen, K.; Goodenough, D.J.; Varghese, B.A. Systematic Approach to Identifying Sources of Variation in CT Radiomics: A Phantom Study. In Proceedings of the 20th International Symposium on Medical Information Processing and Analysis (SIPAIM), Antigua, Guatemala, 13–15 November 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, X.; Song, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Shao, Z. Enhancing the Clinical Utility of Radiomics: Addressing Key Challenges in Repeatability and Reproducibility. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertel, A.; Tharmaseelan, H.; Rotkopf, L.T.; Nörenberg, D.; Riffel, P.; Nikolaou, K.; Weiss, J.; Bamberg, F.; Schoenberg, S.O.; Froelich, M.F. Phantom-based radiomics feature test–retest stability analysis on photon-counting detector CT. Eur. Radiol. 2023, 33, 4905–4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flouris, K.; Jimenez-del-Toro, O.; Aberle, C.; Bach, M.; Schaer, R.; Obmann, M.; Stieltjes, B.; Müller, H.; Depeursinge, A.; Konukoglu, E. Assessing radiomics feature stability with simulated CT acquisitions. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Fleiss, J.L. Intraclass correlation coefficient. In Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences; Kotz, S., Johnson, N.L., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1982; Volume 4, pp. 213–217. [Google Scholar]

- Limkin, E.J.; Sun, R.; Dercle, L.; Zacharaki, E.I.; Robert, C.; Reuzé, S.; Schernberg, A.; Paragios, N.; Deutsch, E.; Ferté, C. Promises and challenges for the implementation of computational medical imaging (radiomics) in oncology. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 1191–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felicetti, F.; Carnì, D.L.; Lamonaca, F. Fish blood cell as biological dosimeter: In between measurements, radiomics, preprocessing, and artificial intelligence. In Innovations in Computational Intelligence and Computer Vision; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Singapore, 2024; Volume 1117. [Google Scholar]

- Perniciano, A.; Loddo, A.; Di Ruberto, C.; Pes, B. Insights into radiomics: Impact of feature selection and classification. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2025, 84, 31695–31721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadipally, M. Optimization of Methods for Image-Texture Segmentation Using Ant Colony Optimization. In Intelligent Data Analysis for Biomedical Applications; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 21–47. [Google Scholar]

- Welvaert, M.; Rosseel, Y. On the definition of signal-to-noise ratio and contrast-to-noise ratio for FMRI data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raunig, D.L.; McShane, L.M.; Pennello, G.; Gatsonis, C.; Carson, P.L.; Voyvodic, J.T.; Wahl, R.L.; Kurland, B.F.; Schwarz, A.J.; Gönen, M.; et al. Quantitative imaging biomarkers: A review of statistical methods for technical performance assessment. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2015, 24, 27–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A.; Shechtman, E.; Wang, O. The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Deep Features as a Perceptual Metric. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 586–595. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal, A.; Moorthy, A.K.; Bovik, A.C. No-Reference Image Quality Assessment in the Spatial Domain. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2012, 21, 4695–4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, L.S.; Rajagopal, H. Modified-BRISQUE as no reference image quality assessment for structural MR images. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2017, 43, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bovik, A.C.; Sheikh, H.R.; Simoncelli, E.P. Image quality assessment: From error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2004, 13, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antonoli, T.A.; Cavallo, A.U.; Vernuccio, F.; Stanzione, A.; Klontzas, M.E.; Cannella, R.; Ugga, L.; Baran, A.; Fanni, S.C.; Petrash, E.; et al. Reproducibility of radiomics quality score: An intra- and inter-rater reliability study. Eur. Radiol. 2024, 34, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayerhoefer, M.A.; Papanikolaou, N.; Aerts, H.J.W.L. Introduction to Radiomics. J. Nucl. Med. 2020, 61, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Patón, M.; Cerdá Alberich, L.; Sangüesa Nebot, C.; Martínez de Las Heras, B.; Veiga Canuto, D.; Cañete Nieto, A.; Martí-Bonmatí, L. MR Denoising Increases Radiomic Biomarker Precision and Reproducibility in Oncologic Imaging. J. Digit. Imaging 2021, 34, 1134–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koçak, B.; Baessler, B.; Bakas, S.; Cuocolo, R.; Fedorov, A.; Maier-Hein, L.; Mercaldo, N.; Müller, H.; Orlhac, F.; dos Santos, D.P.; et al. CheckList for EvaluAtion of Radiomics research (CLEAR): A step-by-step reporting guideline for authors and reviewers endorsed by ESR and EuSoMII. Insights Imaging 2023, 14, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocak, B.; D’Antonoli, T.A.; Mercaldo, N.; Alberich-Bayarri, A.; Baessler, B.; Ambrosini, I.; Andreychenko, A.E.; Bakas, S.; Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; Bressem, K.; et al. METhodological RadiomICs Score (METRICS): A quality scoring tool for radiomics research endorsed by EuSoMII. Insights Imaging 2024, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Concern | CT | PET | MRI | X-Rays | Ultrasound | Typical Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motion | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Patient movement, long acquisition times |

| Beam hardening | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Polychromatic X-ray beams, high-density materials | ||

| Noise | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Low dose, acquisition settings, patient size |

| Blur | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Motion, system resolution limits, reconstruction effects |

| Patient size | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Photon attenuation, scattering, reduced signal-to-noise ratio |

| Artifact Type | Imaging Modality | Affected Feature | Reported Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motion | MRI, PET, CT | Texture, shape | Reduced reproducibility, segmentation errors |

| Beam hardening | CT | First-order, texture | Feature bias, intensity distortion |

| Noise | CT, MRI, PET | Texture (GLCM, GLSZM), first-order | Increased variance, instability |

| Blur | CT, MRI, PET | Texture, shape | Loss of edge definition, misclassification |

| Body habitus | CT, PET | First-order, texture | Contrast loss, increased noise |

| Artifact Type | Mitigation Approach | Level of Application | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motion | Motion correction, AI-based methods | Image-level | Computational cost, modality dependence |

| Beam hardening | Dual-energy CT, iterative reconstruction, deep learning | Acquisition/reconstruction | Hardware availability, training data |

| Noise | Filtering, GAN-based denoising | Image-level | Possible alteration of texture features |

| Blur | Deconvolution, sharpness enhancement | Image-level | Requires PSF estimation |

| Scanner/protocol variability | Statistical harmonization | Feature-level | Requires batch definition, possible signal masking |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Felicetti, F.; Lamonaca, F.; Carnì, D.L.; Costanzo, S. Image Quality Standardization in Radiomics: A Systematic Review of Artifacts, Variability, and Feature Stability. Sensors 2026, 26, 1039. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26031039

Felicetti F, Lamonaca F, Carnì DL, Costanzo S. Image Quality Standardization in Radiomics: A Systematic Review of Artifacts, Variability, and Feature Stability. Sensors. 2026; 26(3):1039. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26031039

Chicago/Turabian StyleFelicetti, Francesco, Francesco Lamonaca, Domenico Luca Carnì, and Sandra Costanzo. 2026. "Image Quality Standardization in Radiomics: A Systematic Review of Artifacts, Variability, and Feature Stability" Sensors 26, no. 3: 1039. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26031039

APA StyleFelicetti, F., Lamonaca, F., Carnì, D. L., & Costanzo, S. (2026). Image Quality Standardization in Radiomics: A Systematic Review of Artifacts, Variability, and Feature Stability. Sensors, 26(3), 1039. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26031039