Personalized Federated Learning with Hierarchical Two-Branch Aggregation for Few-Shot Scenarios

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We propose a novel pFL framework pFedH2A. It simulates the division of labor mechanism in different regions of the human brain when processing perception and representation information, and performs personalized aggregation of hierarchical modules in neural networks.

- We design a dual-branch hypernetwork (DHN) that moves beyond the monolithic parameter generation of conventional hypernetworks. By explicitly decoupling the generation process into perceptual and representational streams, DHN enables fine-grained, layer-adaptive aggregation that balances generalization and personalization, a capability lacking in single-stream approaches.

- We design a relation-aware module that learns an adaptive similarity function for each client. Unlike standard methods that rely on fixed distance metrics, this module constructs a learnable metric to determine class membership, enabling effective discrimination in heterogeneous few-shot scenarios.

- We conduct extensive experiments on three public image classification datasets and demonstrate that pFedH2A outperforms other baseline pFL methods in accuracy under few-shot scenarios.

2. Related Work

2.1. Few-Shot Learning

2.2. Personalized Federated Learning

2.3. Hypernetwork in Federated Learning

3. Proposed Method

3.1. Problem Formulation

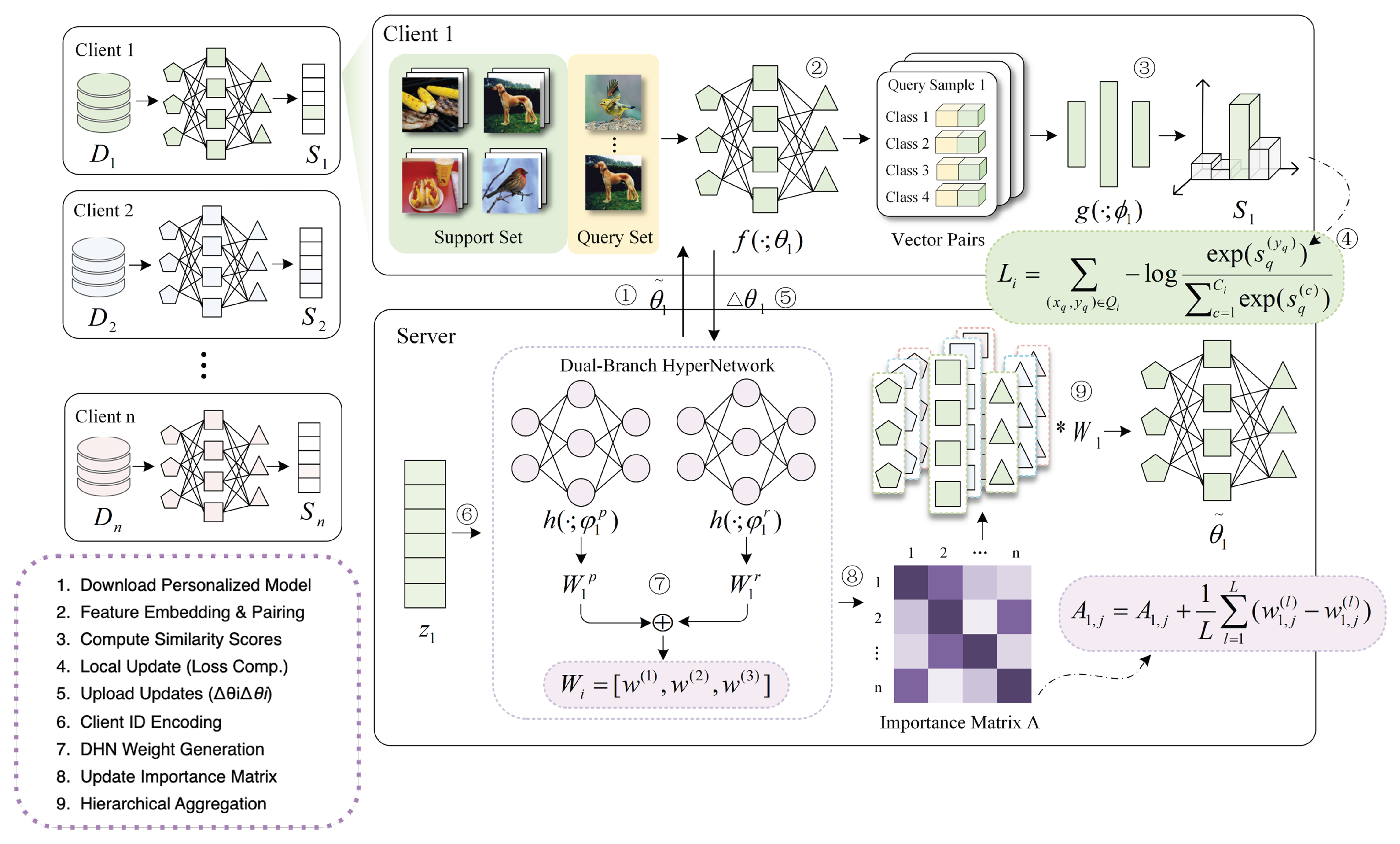

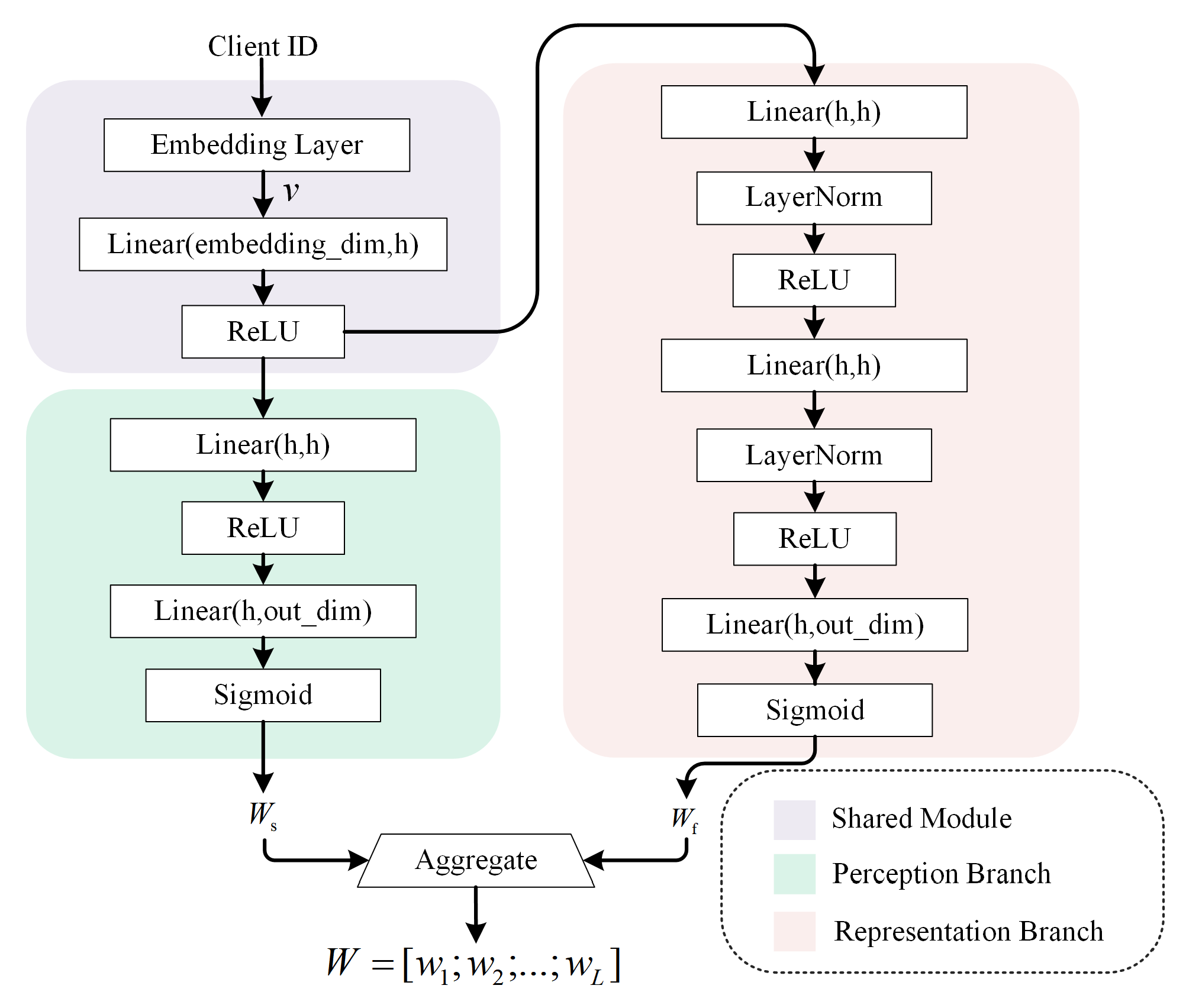

3.2. Hierarchical Personalized Aggregation via the Dual-Branch Hypernetwork

3.3. Relation-Aware Personalized Federated Learning for Few-Shot Scenarios

3.4. Overall Workflow

| Algorithm 1 pFedH2A Algorithm |

|

- 1.

- Weight Generation: The server encodes the target client identity into and feeds it into the DHN to generate perception and representation weights. These are fused via to produce the final hierarchical weight matrix .

- 2.

- Reference Selection: The importance matrix A is dynamically updated based on the generated weights to reflect the current correlation between clients. Using this updated matrix, the server identifies a set of reference clients to participate in the aggregation.

- 3.

- Hierarchical Aggregation: The personalized model is constructed by aggregating the parameters of the selected reference clients layer-by-layer, using the specific weights assigned in to distinctively combine shallow and deep features.

4. Experiment

4.1. Experimental Setup

- Dataset. We evaluate the performance of the proposed method on three public datasets: MNIST, CIFAR-10, and CIFAR-100. MNIST, a classic baseline for handwritten digit recognition, consists of 70,000 grayscale images of 28 × 28 pixels, evenly distributed across 10 digit classes (0–9). CIFAR-10 targets general object classification tasks, comprising 60,000 RGB images of 32 × 32 pixels across 10 basic categories, including airplanes, automobiles, and birds. As an extended version, CIFAR-100 maintains the same image resolution but increases the number of categories to 100, thus raising the difficulty of the classification task.

- Random heterogeneous allocation: This method constructs heterogeneous client data distributions through a randomization mechanism. Specifically, the number of classes contained in each client’s local dataset is randomly selected from . Then, the number of samples is randomly chosen from for each selected class. This method creates a unique task space for each client and enhances data heterogeneity.

- Cluster-sharing allocation: This method partitions all clients into groups, with each group assigned C target classes to ensure that clients within the same group share a similar task structure. Based on this, training samples are drawn for each client within the cluster using a Dirichlet distribution. This method enables task space sharing within clusters while preserving a certain degree of individual diversity.

- Baseline. We use a systematic comparative experimental framework to compare pFedH2A with five baseline methods, including a classic FL method (FedAvg) and four representative pFL methods (FedFomo, FedBN, pFedHN, pFedFSL).

- FedAvg [38] is a classic FL method that obtains a global model by weighted averaging the local models sent by clients.

- FedFomo [5] learns the optimal weighted combination for each personalized model by calculating the importance between client models.

- FedBN [39] proposed a scheme for cross-client parameter sharing, where each client’s Batch Normalization(BN) layer is updated locally, and other layers are aggregated based on the FedAvg.

- pFedHN [28] generates personalized models directly for each client through a hypernetwork deployed on the server.

- FedFSL [8] is a FedAvg-based method by combines meta-learning techniques such as MAML with adversarial objectives to encourage the construction of a unified and discriminative feature space across clients.

- pFedFSL [9] is a pFL framework in few-shot learning scenarios that enhances the ability to handle sparse data by constructing prototypes for local data.

- Configuration. For the above methods, we set the number of clients to 30, the communication round to 500, the local training round to 5, and the optimizer to select SGD with a learning rate of . For methods using hypernetworks (pfedhn and our method), the hypernetwork learning rate is uniformly set at . For our method, the coefficient is set to .

4.2. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.2.1. Comparison Experiment

4.2.2. Ablation Experiment

- Variant 1: Randomly select reference clients during the aggregation process instead of using the importance matrix for model selection.

- Variant 2: Remove the hierarchical aggregation structure and adopt a overall model aggregation approach.

- Variant 3: Remove the dual-branch hypernetwork design and generate aggregation weights using a single-branch hypernetwork.

- Variant 4: Replace the adaptive relation-aware similarity module with a standard fixed Euclidean distance metric (similar to Prototypical Networks) to evaluate the benefit of the learnable metric.

- Variant 5: Replace the adaptive fusion coefficient with a fixed value (set to ) to evaluate the necessity of the dynamic fusion mechanism.

4.2.3. Cluster Sensitivity Analysis

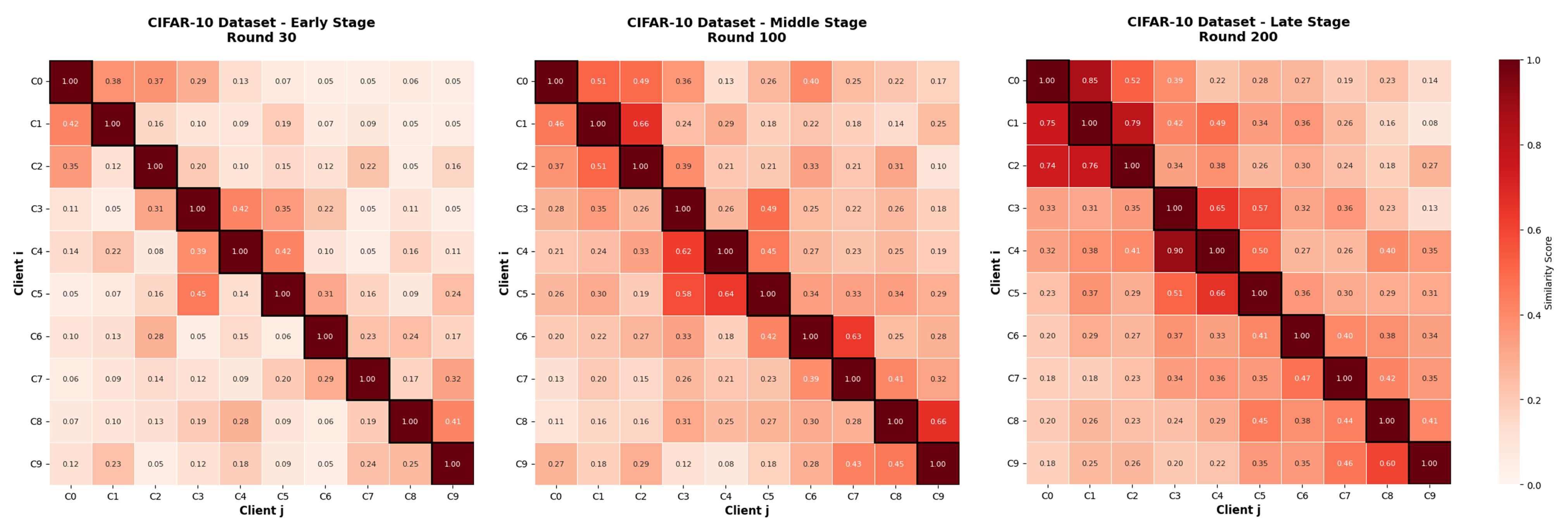

4.2.4. Importance Evolution Analysis

- Round 30: At the early stage, the importance scores between clients are relatively low, which is expected under heterogeneous data distributions. Each client’s personalized model primarily learns from its local data, resulting in significant divergence among models.

- Round 100: By the middle stage, as aggregation progresses, certain clients begin to show higher importance scores with others, indicating that the importance matrix facilitates convergence by selectively enhancing collaboration.

- Round 200: In the late stage, most clients exhibit high mutual importance scores, suggesting that their models have converged toward similar representations. Nonetheless, a few clients still maintain lower scores due to the distinctive characteristics of their local data.

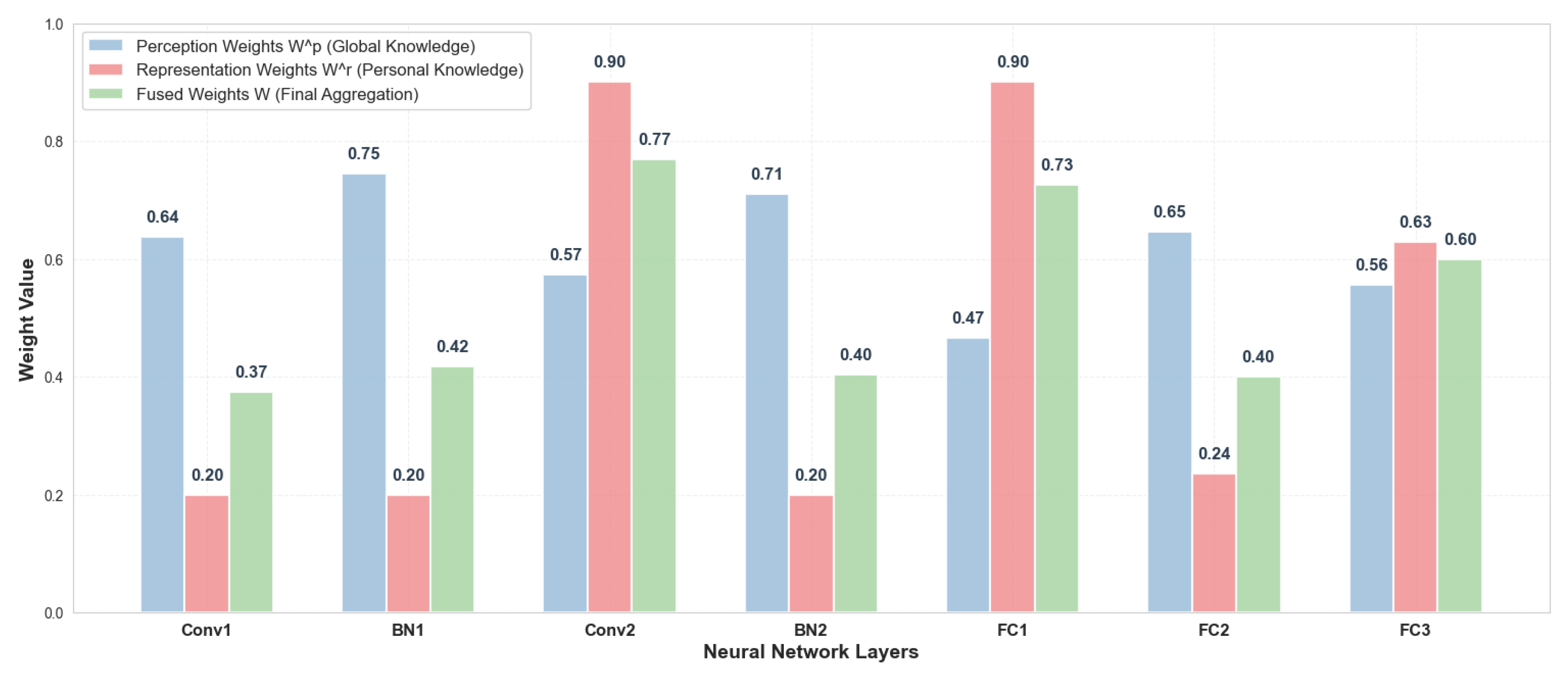

4.2.5. Hierarchical Weight Fusion Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hao, D.; Yang, Y.; Ye, H.; Chang, X. Ppfl: A personalized federated learning framework for heterogeneous population. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.14337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barch, D.M. Brain network interactions in health and disease. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2013, 17, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, L.; Ma, M.; He, P.; Geng, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, F.; Ma, W.; Yang, S.; Hou, B.; Tang, X. Brain-inspired learning, perception, and cognition: A comprehensive review. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 6, 5921–5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Chu, L.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Pei, J.; Zhang, Y. Personalized cross-silo federated learning on non-iid data. Proc. Aaai Conf. Artif. Intell. 2021, 35, 7865–7873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Sapra, K.; Fidler, S.; Yeung, S.; Alvarez, J.M. Personalized federated learning with first order model optimization. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.08565. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, J.; Guo, S.; Xu, W. Layer-wised model aggregation for personalized federated learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 10092–10101. [Google Scholar]

- Yosinski, J.; Clune, J.; Bengio, Y.; Lipson, H. How transferable are features in deep neural networks? In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 27: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2014, Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–13 December 2014; pp. 3320–3328. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, C.; Huang, J. Federated few-shot learning with adversarial learning. In 2021 19th International Symposium on Modeling and Optimization in Mobile, Ad Hoc, and Wireless Networks (WiOpt); IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Yu, G.; Wang, J.; Domeniconi, C.; Guo, M.; Zhang, X.; Cui, L. Personalized federated few-shot learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 35, 2534–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Zhang, J.; Tsang, D.H.K. Fedfa: Federated learning with feature anchors to align features and classifiers for heterogeneous data. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2023, 23, 6731–6742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, R.; Halgamuge, S. Discriminative sample-guided and parameter-efficient feature space adaptation for cross-domain few-shot learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 23794–23804. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Gu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, J.; Wei, Y. Relation networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 3588–3597. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Li, C.; Ding, P.; Li, S.; Li, T.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Hong, Z. A novel transformer-based few-shot learning method for intelligent fault diagnosis with noisy labels under varying working conditions. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 251, 110400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Wei, C. Few-shot classification for isar images of space targets by complexvalued patch graph transformer. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2024, 60, 4896–4909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xu, H.; Darrell, T.; Wang, X. Meta-baseline: Exploring simple meta-learning for few-shot learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 9062–9071. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Wang, Y.; Krishnan, D.; Tenenbaum, J.B.; Isola, P. Rethinking few-shot image classification: A good embedding is all you need? In Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Proceedings, Part XIV 16; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 266–282. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Cheng, C.-W.; He, J.; He, Z.; Schönlieb, C.-B.; Chen, Y.; Aviles-Rivero, A.I. Cross-modal few-shot learning with second-order neural ordinary differential equations. Proc. Aaai Conf. Artif. Intell. 2025, 39, 10302–10310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, A.K.; Balamurugan, G.; Kumar, D.; Kumari, S. Natural Language Processing (NLP)-Based Intelligence for Pattern Mining Using Artificial Intelligence, Robotics, and Cloud Computing; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, L.; Silven, O.; Pietikäinen, M.; Hu, D. Few-shot class-incremental learning for classification and object detection: A survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025, 47, 2924–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Kamani, M.M.; Mahdavi, M. Adaptive personalized federated learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.13461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, T.; Canh; Tran, N.; Nguyen, J. Personalized federated learning with moreau envelopes. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 21394–21405. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, L.; Hassani, H.; Mokhtari, A.; Shakkottai, S. Exploiting shared representations for personalized federated learning. In International Conference on Machine Learning; PMLR: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 2089–2099. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Hua, Y.; Wang, H.; Song, T.; Xue, Z.; Ma, R.; Guan, H. Fedala: Adaptive local aggregation for personalized federated learning. Proc. Aaai Conf. Artif. Intell. 2023, 37, 11237–11244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, A.; Mokhtari, A.; Ozdaglar, A. Personalized federated learning with theoretical guarantees: A model-agnostic meta-learning approach. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 3557–3568. [Google Scholar]

- Hanzely, F.; Hanzely, S.; Horváth, S.; Richtárik, P. Lower bounds and optimal algorithms for personalized federated learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 2304–2315. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Hu, S.; Beirami, A.; Smith, V. Ditto: Fair and robust federated learning through personalization. In International Conference on Machine Learning; PMLR: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 6357–6368. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, D.; Pawar, P.P.; Meesala, M.K.; Pareek, P.K.; Addula, S.R.; KS, S. Trustworthy iot infrastructures: Privacy-preserving federated learning with efficient secure aggregation for cybersecurity. In 2024 International Conference on Integrated Intelligence and Communication Systems (ICIICS); IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsian, A.; Navon, A.; Fetaya, E.; Chechik, G. Personalized federated learning using hypernetworks. In International Conference on Machine Learning; PMLR: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 9489–9502. [Google Scholar]

- Ridolfi, L.; Naseh, D.; Shinde, S.S.; Tarchi, D. Implementation and evaluation of a federated learning framework on raspberry pi platforms for iot 6g applications. Future Internet 2023, 15, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yin, J.; Zhang, W.; An, C.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, H. Integration of federated learning and ai-generated content: A survey of overview, opportunities, challenges, and solutions. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2025, 27, 3308–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Xia, W.; Lu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Hypernetwork-based personalized federated learning for multi-institutional ct imaging. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.03709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Zeng, S.; Chen, W.; Zhang, X.; Ren, W.; Zhou, Y.; Qu, L. A new federated learning framework against gradient inversion attacks. Proc. Aaai Conf. Artif. Intell. 2025, 39, 16969–16977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Lee, K.; Lee, S.; Choi, Y.R.; Kim, H.-S.; Ko, J. Effective heterogeneous federated learning via efficient hypernetwork-based weight generation. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM Conference on Embedded Networked Sensor Systems, Hangzhou, China, 4–7 November 2024; pp. 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Huang, H.; Wang, Z.; Fu, X.; Hong, D.; Gupta, R.K.; Shang, J. How few davids improve one goliath: Federated learning in resource-skewed edge computing environments. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2024, Singapore, 13–17 May 2024; pp. 2976–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Xia, W.; Lu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Hypernetwork-based physics-driven personalized federated learning for ct imaging. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 36, 3136–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Bao, Z.; Miao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, W. A personalized and differentially private federated learning for anomaly detection of industrial equipment. IEEE J. Radio Freq. Identif. 2024, 8, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijwel, M.M. Artificial neural networks advantages and disadvantages. Mesopotamian J. Big Data 2021, 2021, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, K.; Yang, W.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z. On the convergence of fedavg on non-iid data. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.02189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, X.; Kamp, M.; Dou, Q. Fedbn: Federated learning on non-iid features via local batch normalization. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.07623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | MNIST | CIFAR-10 | CIFAR-100 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (3, 5) | (3, 20) | (5, 5) | (5, 20) | (3, 5) | (3, 20) | (5, 5) | (5, 20) | (5, 5) | (5, 20) | (20, 5) | (20, 20) | |

| FedAvg | 0.9077 | 0.9220 | 0.8799 | 0.9485 | 0.3121 | 0.4012 | 0.2854 | 0.3669 | 0.1002 | 0.1896 | 0.1077 | 0.1371 |

| FedFomo | 0.9069 | 0.9355 | 0.9114 | 0.9451 | 0.4157 | 0.5302 | 0.3602 | 0.4101 | 0.3572 | 0.4903 | 0.2101 | 0.3016 |

| FedBN | 0.9176 | 0.9548 | 0.8956 | 0.9399 | 0.3202 | 0.4223 | 0.2988 | 0.3851 | 0.3340 | 0.4851 | 0.1365 | 0.1845 |

| pFedHN | 0.9143 | 0.9401 | 0.8959 | 0.9406 | 0.4540 | 0.5724 | 0.3933 | 0.4863 | 0.2910 | 0.3896 | 0.1480 | 0.1853 |

| FedFSL | 0.9014 | 0.9746 | 0.9096 | 0.9601 | 0.5231 | 0.6278 | 0.4003 | 0.5428 | 0.2430 | 0.4269 | 0.1874 | 0.2879 |

| pFedFSL | 0.9234 | 0.9732 | 0.9326 | 0.9747 | 0.5757 | 0.7310 | 0.4557 | 0.5890 | 0.4832 | 0.6489 | 0.2345 | 0.3968 |

| pFedH2A | 0.9494 | 0.9801 | 0.9401 | 0.9753 | 0.6656 | 0.7561 | 0.4755 | 0.6152 | 0.5362 | 0.6733 | 0.2717 | 0.4012 |

| Method | MNIST | CIFAR-10 | CIFAR-100 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (3, 5) | (3, 20) | (5, 5) | (5, 20) | (3, 5) | (3, 20) | (5, 5) | (5, 20) | (5, 5) | (5, 20) | (20, 5) | (20, 20) | |

| FedAvg | 0.9213 | 0.9495 | 0.8978 | 0.9433 | 0.3233 | 0.4085 | 0.3156 | 0.3656 | 0.2547 | 0.3946 | 0.1464 | 0.1745 |

| FedFomo | 0.9380 | 0.9708 | 0.9122 | 0.9619 | 0.5311 | 0.5922 | 0.4488 | 0.5313 | 0.4604 | 0.5670 | 0.2315 | 0.3224 |

| FedBN | 0.9326 | 0.9492 | 0.9273 | 0.9553 | 0.5044 | 0.5617 | 0.4127 | 0.5045 | 0.4304 | 0.5657 | 0.1845 | 0.2642 |

| pFedHN | 0.9367 | 0.9619 | 0.9240 | 0.9583 | 0.5881 | 0.6256 | 0.4767 | 0.5797 | 0.4480 | 0.5633 | 0.2107 | 0.2965 |

| FedFSL | 0.9130 | 0.9538 | 0.9190 | 0.9462 | 0.5547 | 0.7030 | 0.4593 | 0.6003 | 0.4458 | 0.5603 | 0.2809 | 0.3001 |

| pFedFSL | 0.9386 | 0.9740 | 0.9400 | 0.9741 | 0.6529 | 0.7388 | 0.5406 | 0.6681 | 0.5997 | 0.6746 | 0.3406 | 0.4870 |

| pFedH2A | 0.9688 | 0.9892 | 0.9569 | 0.9780 | 0.7339 | 0.8393 | 0.6180 | 0.6974 | 0.6738 | 0.7523 | 0.3866 | 0.5121 |

| Method | MNIST | CIFAR-10 | CIFAR-100 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (5, 5) | (5, 20) | (5, 5) | (5, 20) | (5, 5) | (5, 20) | |

| Variant 1 | 0.9318 | 0.9773 | 0.5231 | 0.6576 | 0.5722 | 0.7412 |

| Variant 2 | 0.9280 | 0.9680 | 0.5345 | 0.6438 | 0.5671 | 0.7239 |

| Variant 3 | 0.9025 | 0.9681 | 0.5313 | 0.6436 | 0.6028 | 0.7388 |

| Variant 4 | 0.9400 | 0.9741 | 0.5406 | 0.6681 | 0.5997 | 0.6746 |

| Variant 5 | 0.9504 | 0.9701 | 0.5820 | 0.6981 | 0.6314 | 0.6991 |

| pFedH2A | 0.9569 | 0.9780 | 0.6180 | 0.6974 | 0.6738 | 0.7523 |

| Allocation Method | Clusters | MNIST | CIFAR10 | CIFAR100 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | Avg | Max | Avg | Max | Avg | ||

| Cluster Sharing | 1 | 0.9840 | 0.9697 | 0.6549 | 0.6270 | 0.8068 | 0.7434 |

| 3 | 0.9614 | 0.9453 | 0.6326 | 0.6026 | 0.7280 | 0.6583 | |

| 5 | 0.9569 | 0.9498 | 0.6180 | 0.5758 | 0.6738 | 0.6191 | |

| 10 | 0.9391 | 0.9335 | 0.5825 | 0.5463 | 0.6179 | 0.5971 | |

| 15 | 0.9413 | 0.9288 | 0.5708 | 0.5293 | 0.5571 | 0.5407 | |

| 30 | 0.9400 | 0.9337 | 0.4773 | 0.4579 | 0.5400 | 0.5143 | |

| Random Heterogeneous | – | 0.9401 | 0.9320 | 0.4755 | 0.4583 | 0.5362 | 0.5036 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Miao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, L.; Zhang, B. Personalized Federated Learning with Hierarchical Two-Branch Aggregation for Few-Shot Scenarios. Sensors 2026, 26, 1037. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26031037

Miao Y, Zhang W, Wang Y, Liu Y, Zhang Z, Meng L, Zhang B. Personalized Federated Learning with Hierarchical Two-Branch Aggregation for Few-Shot Scenarios. Sensors. 2026; 26(3):1037. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26031037

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiao, Yifan, Weishan Zhang, Yuhan Wang, Yuru Liu, Zhen Zhang, Lingzhao Meng, and Baoyu Zhang. 2026. "Personalized Federated Learning with Hierarchical Two-Branch Aggregation for Few-Shot Scenarios" Sensors 26, no. 3: 1037. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26031037

APA StyleMiao, Y., Zhang, W., Wang, Y., Liu, Y., Zhang, Z., Meng, L., & Zhang, B. (2026). Personalized Federated Learning with Hierarchical Two-Branch Aggregation for Few-Shot Scenarios. Sensors, 26(3), 1037. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26031037