Reliable Automated Displacement Monitoring Using Robotic Total Station Assisted by a Fixed-Length Track

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

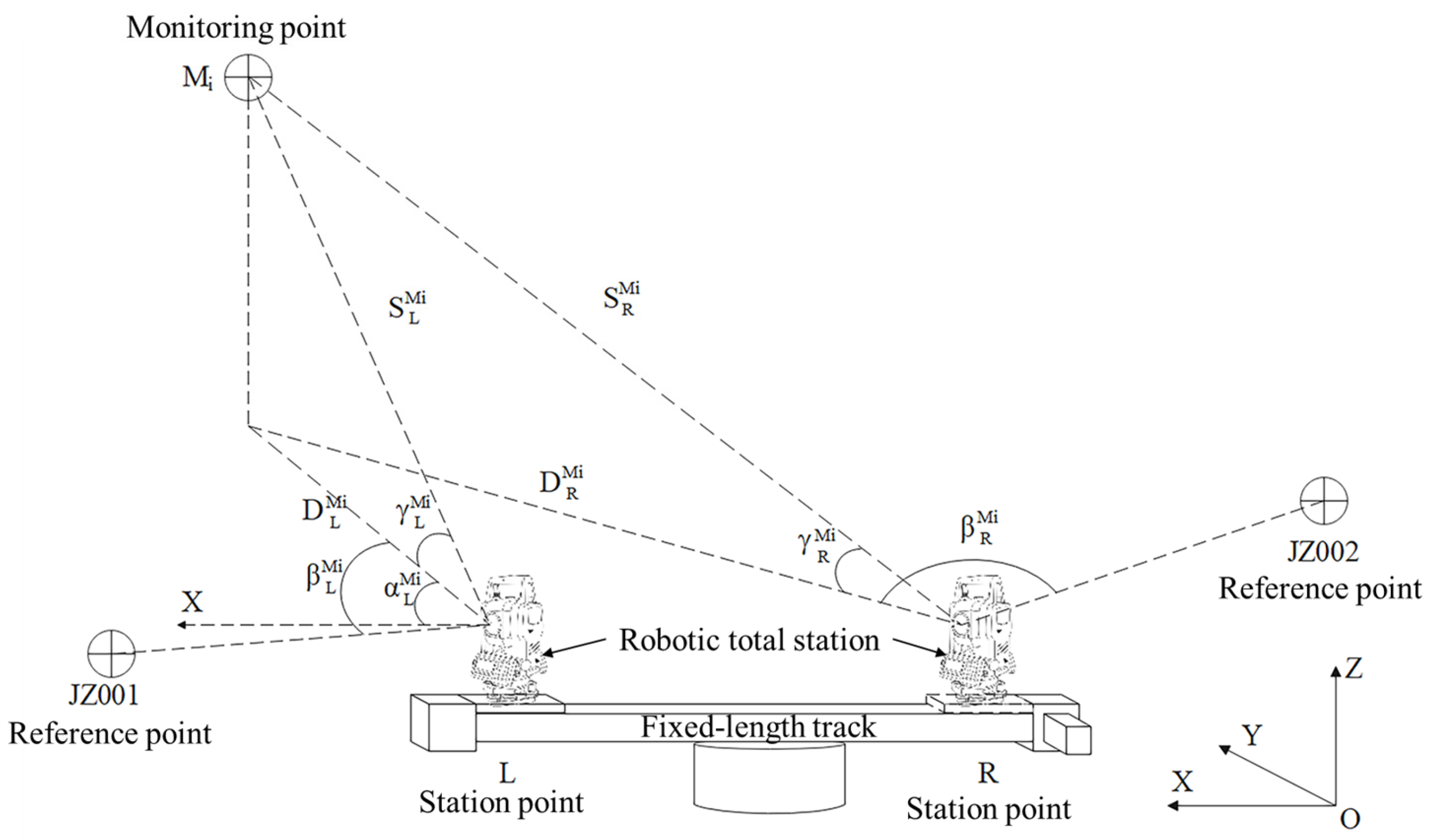

2.1. Mathematical Principles

2.1.1. Manual Training and Automated Monitoring

2.1.2. Calculation of Coordinates of Monitoring Points

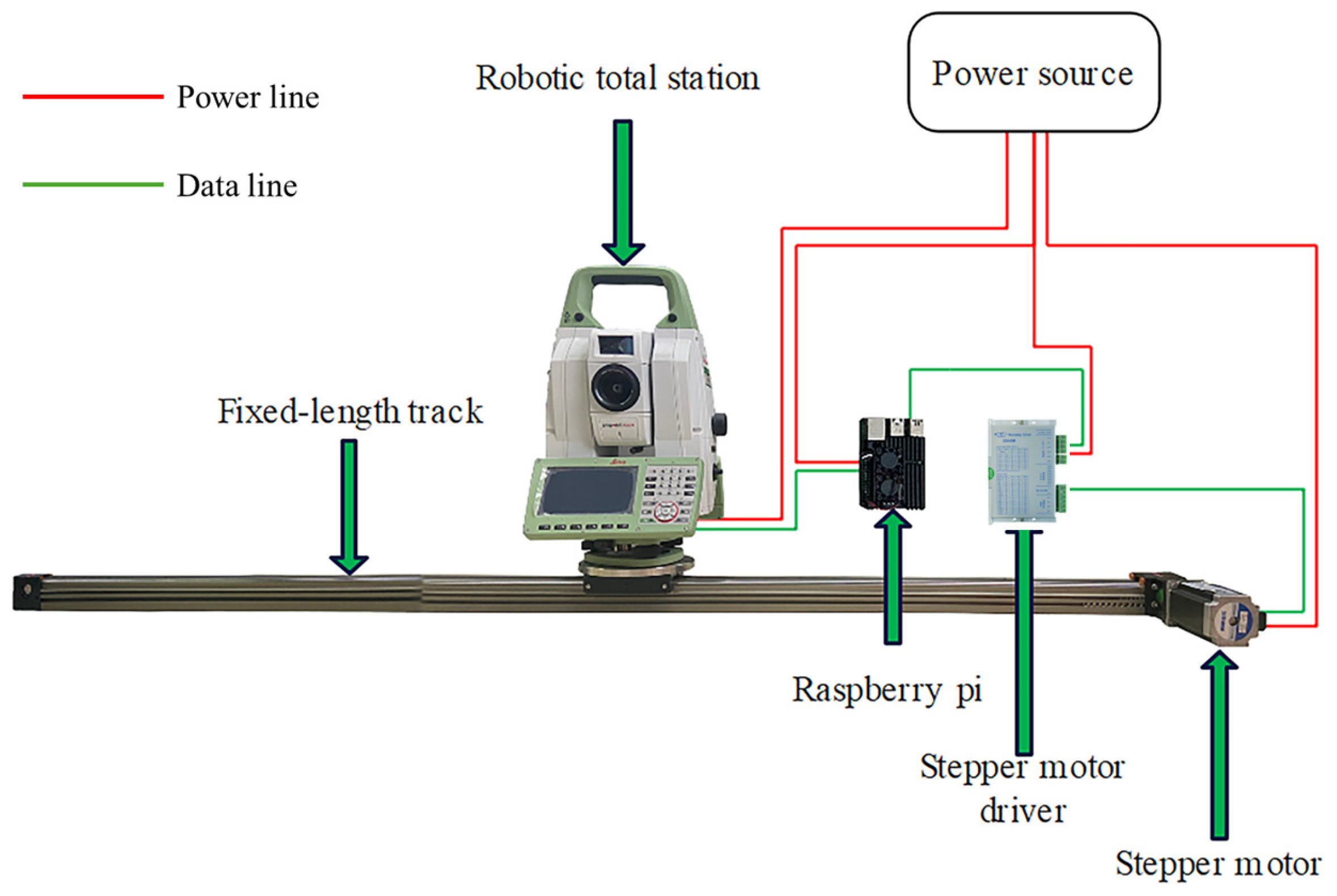

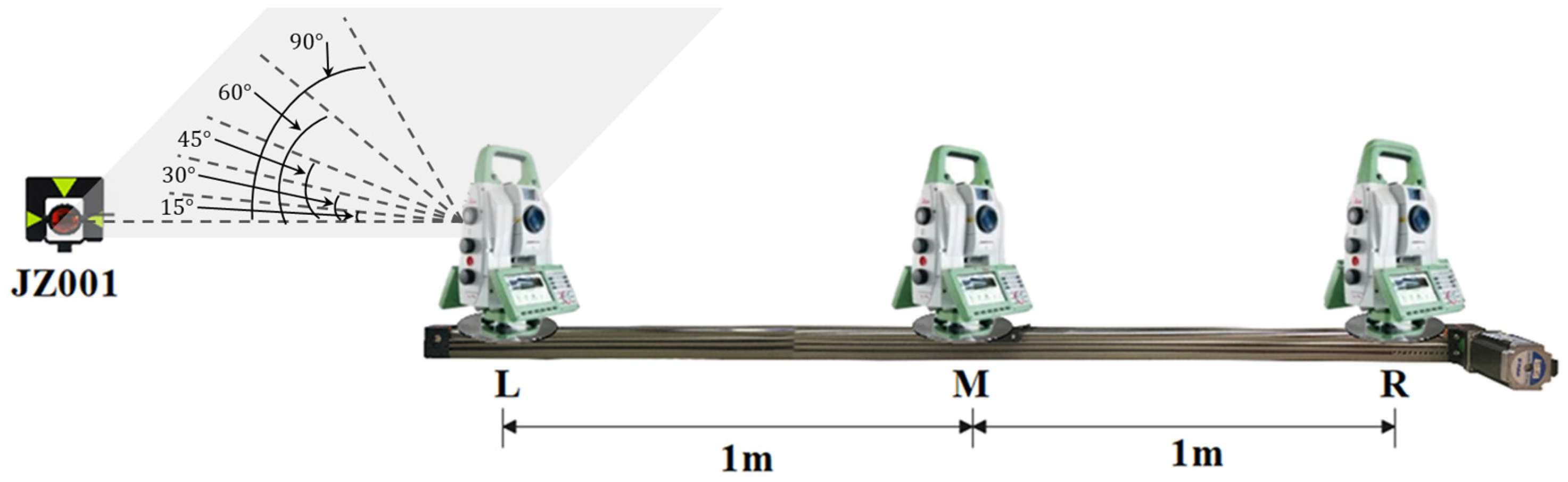

2.2. System Components

3. Experiments and Results

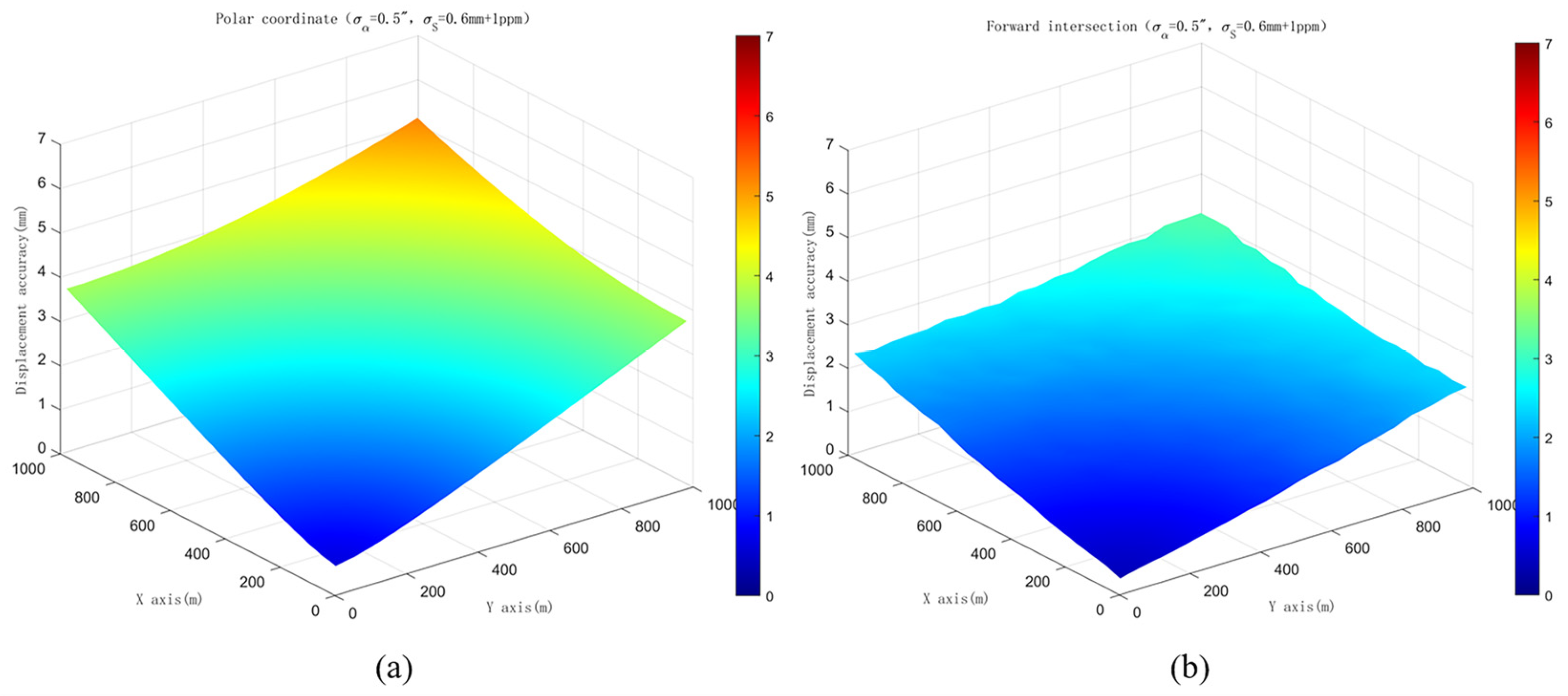

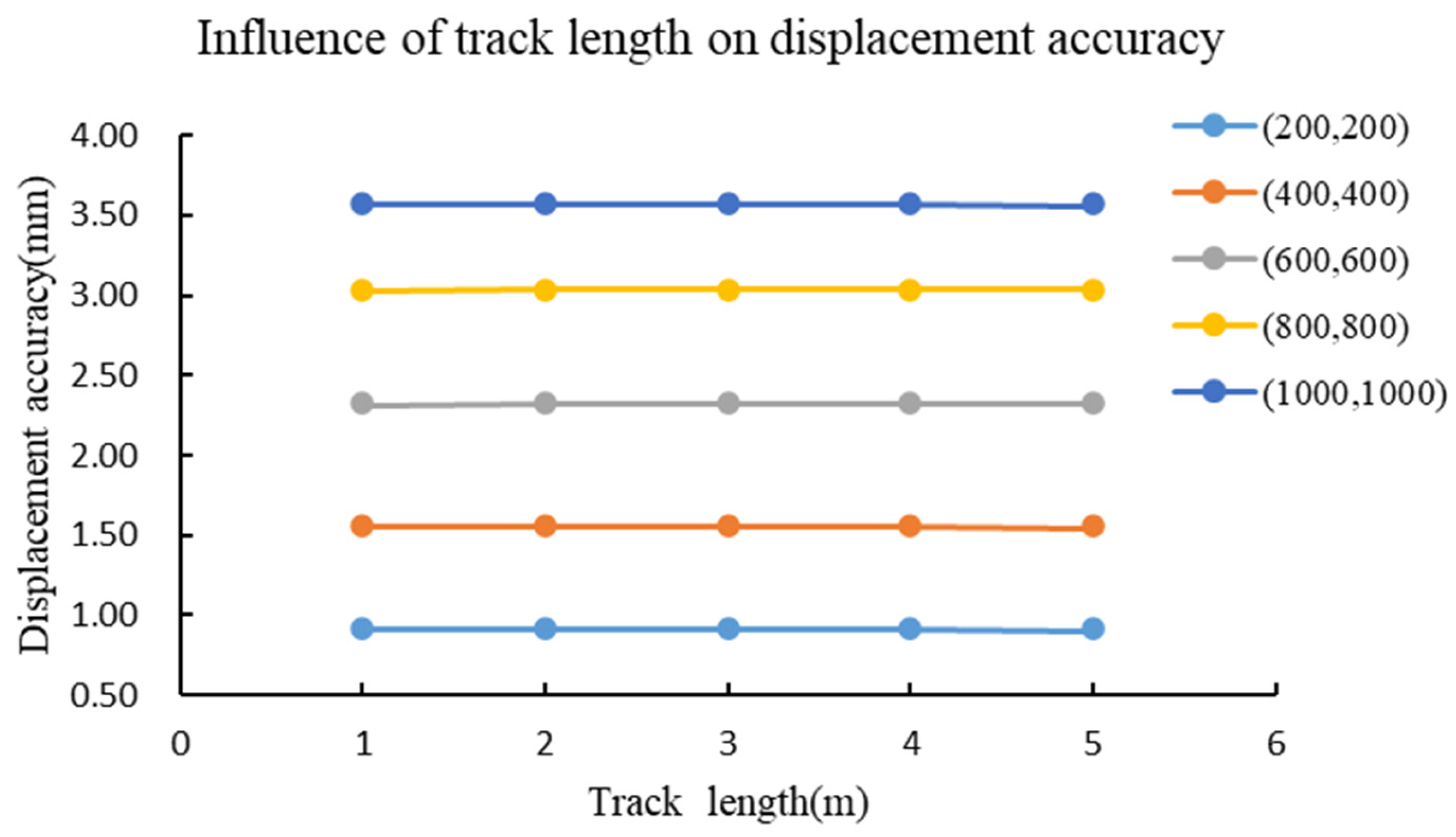

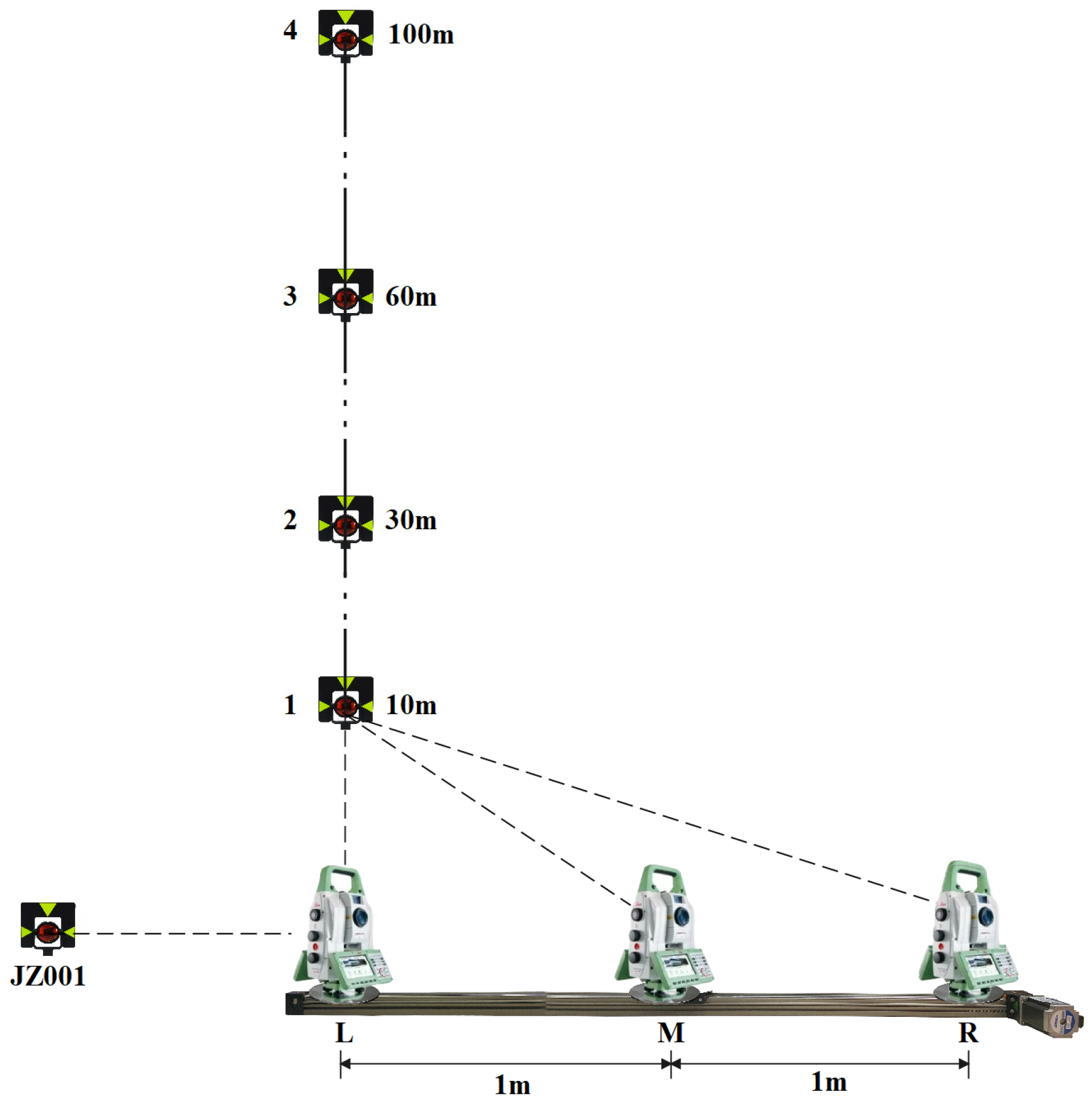

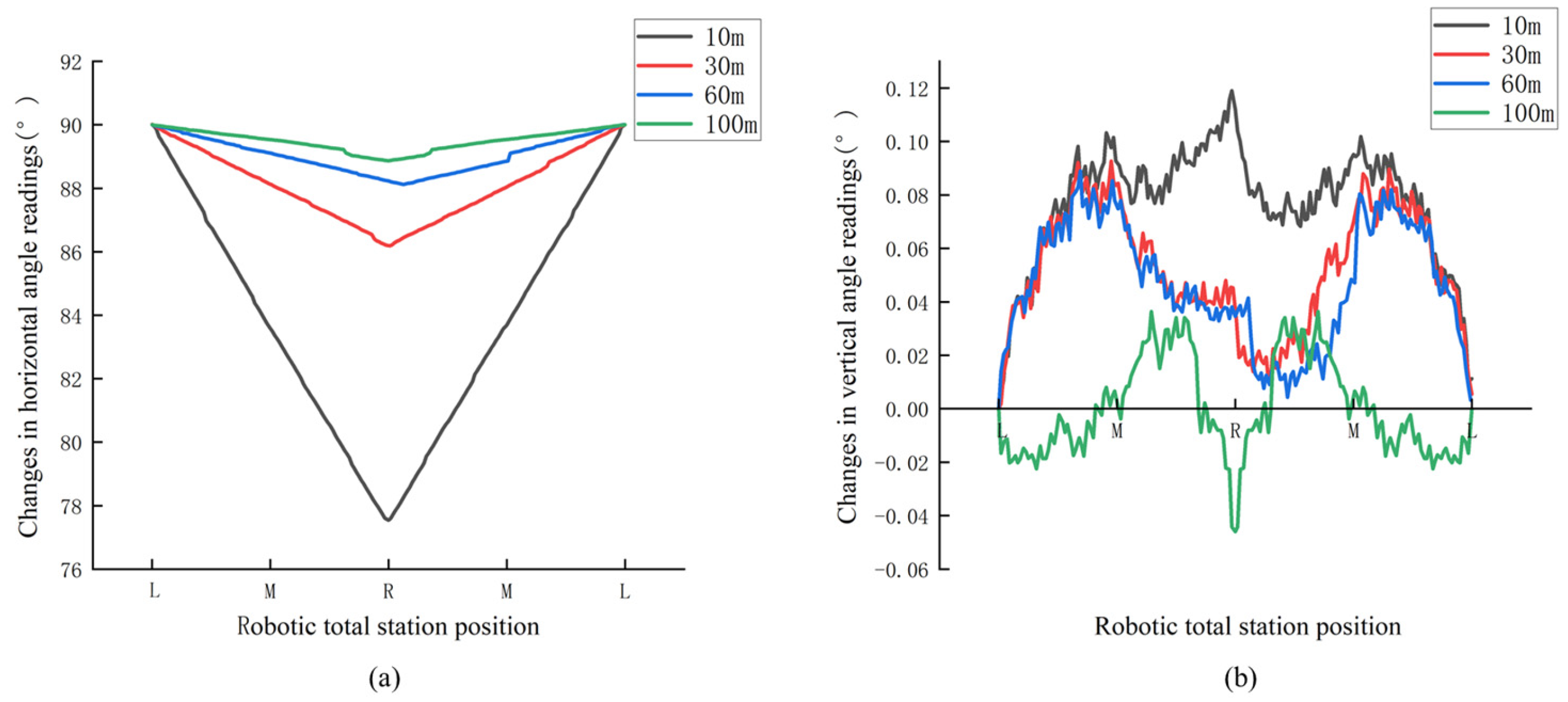

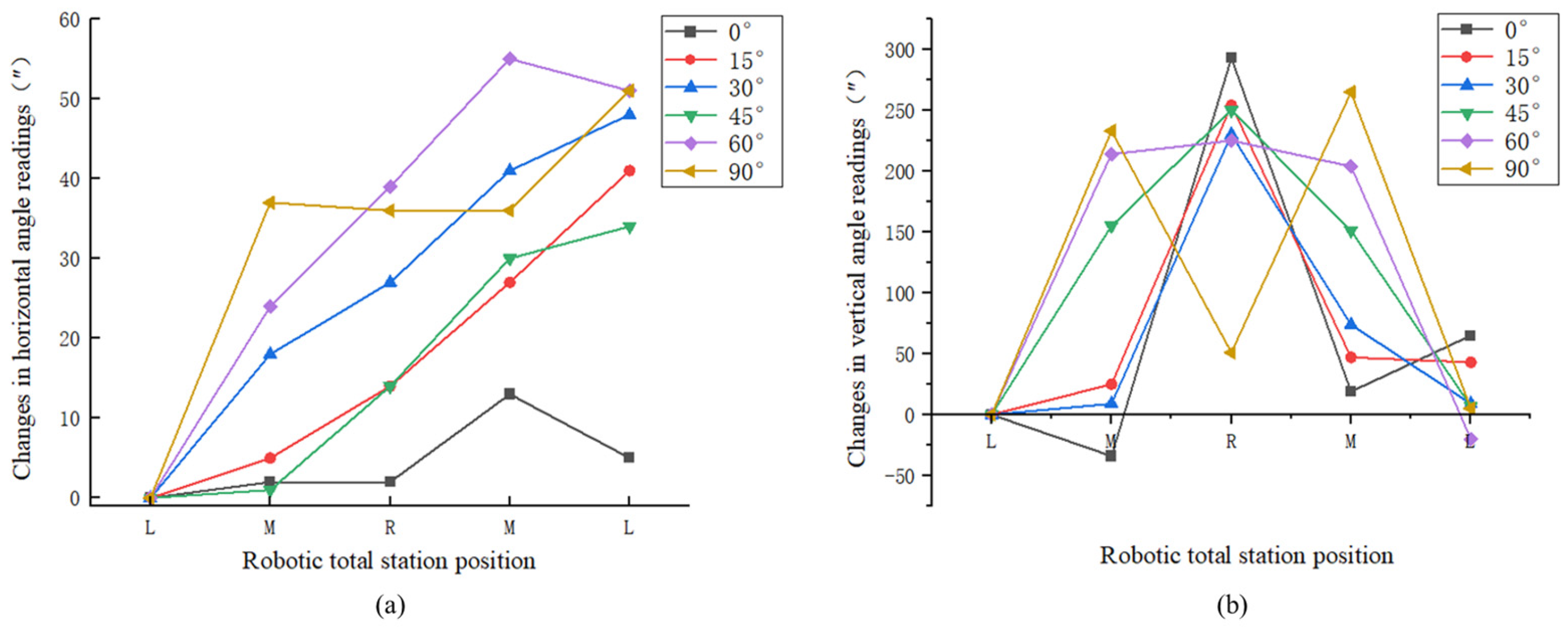

3.1. Simulations

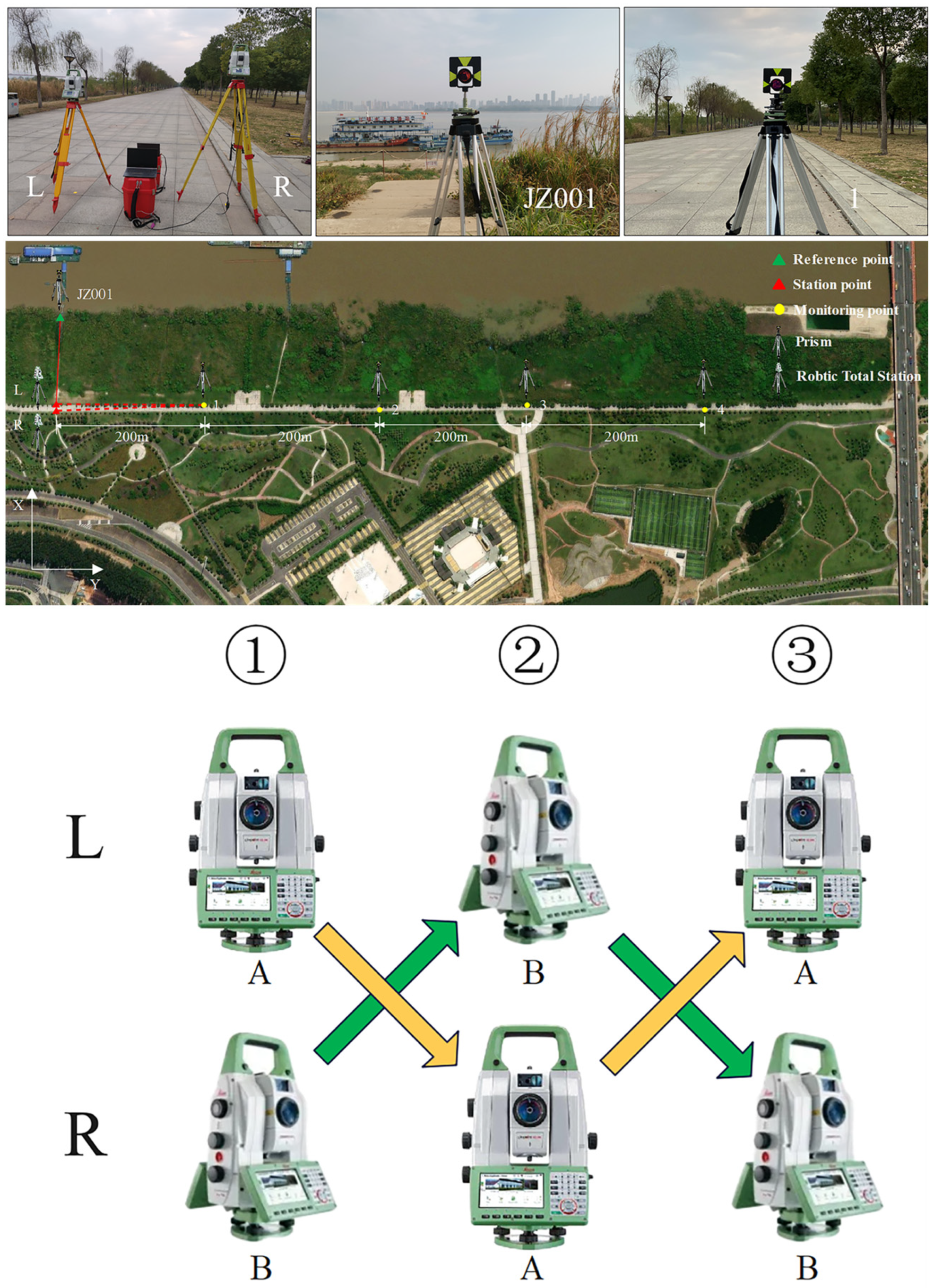

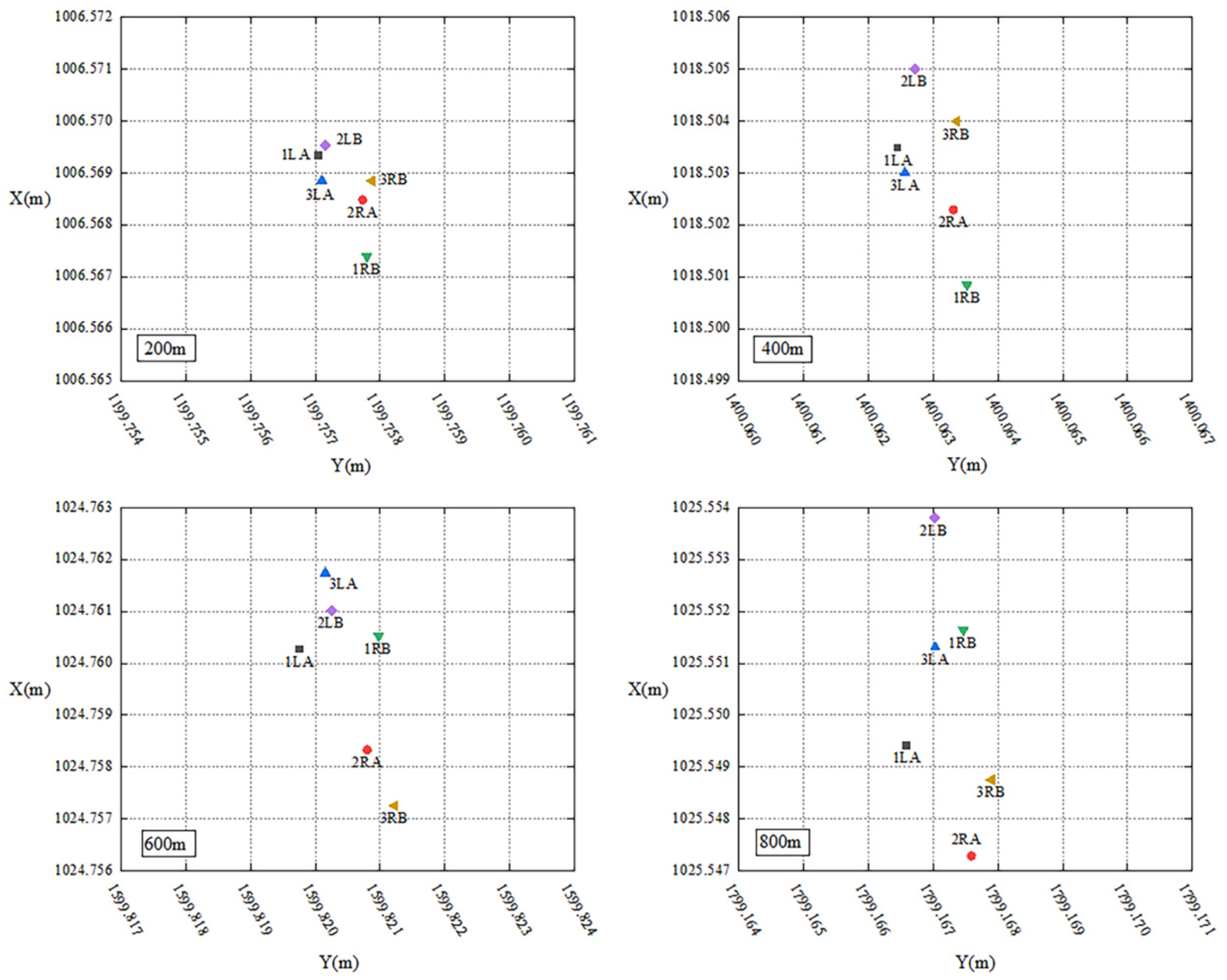

3.2. Feasibility Tests

- (1)

- Set up a robotic total station at station point and at . Utilize the automated monitoring software to obtain observations for each monitoring point and record them as and , respectively.

- (2)

- Remove and from their tribraches and exchange their positions. In other words, place robotic total station at station point and at . Run another round of automated monitoring and record the observations as and .

- (3)

- Once again, exchange the positions of robotic total station and and return to the setup in step (1). Conduct a new round of automated monitoring and record the observations as and .

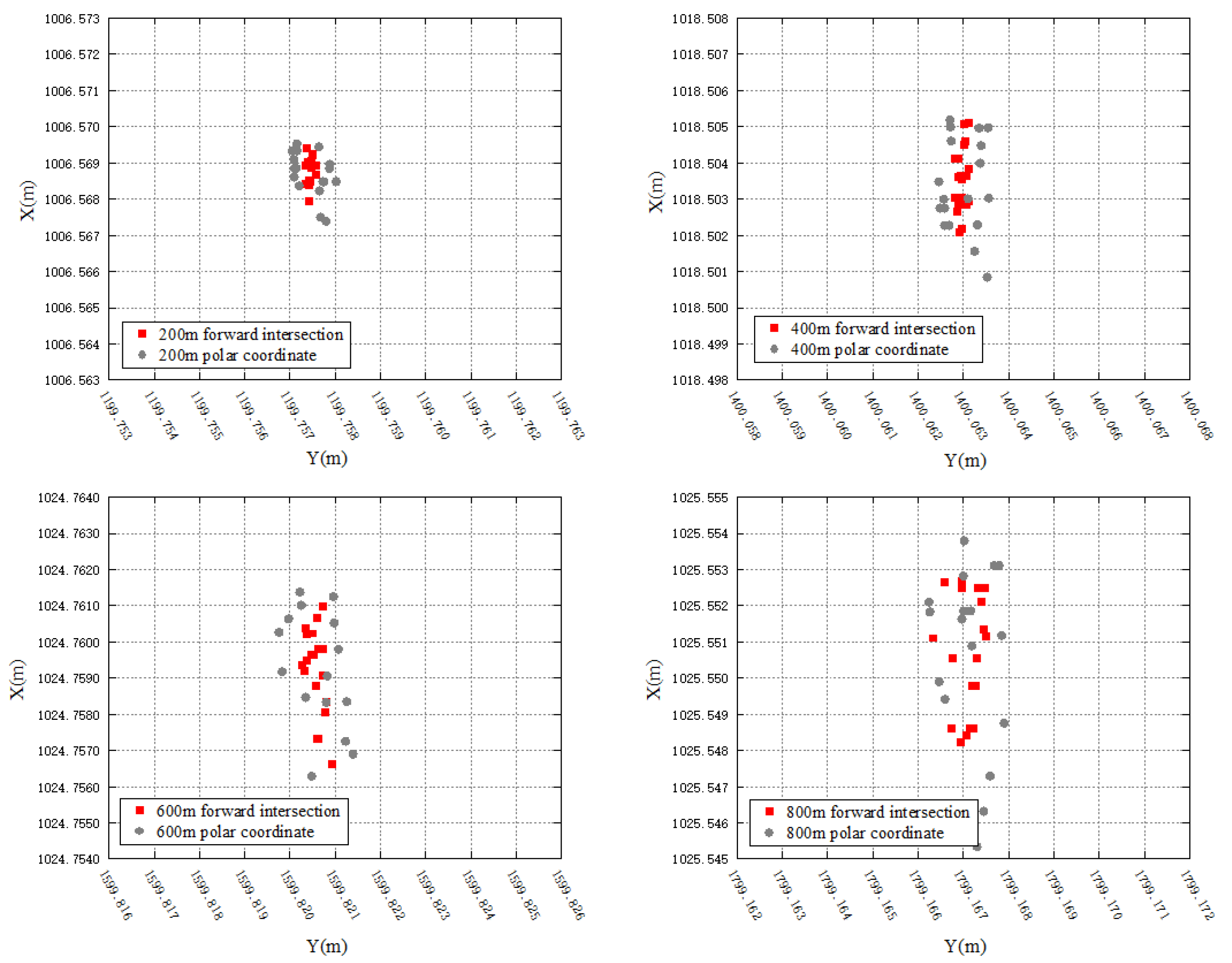

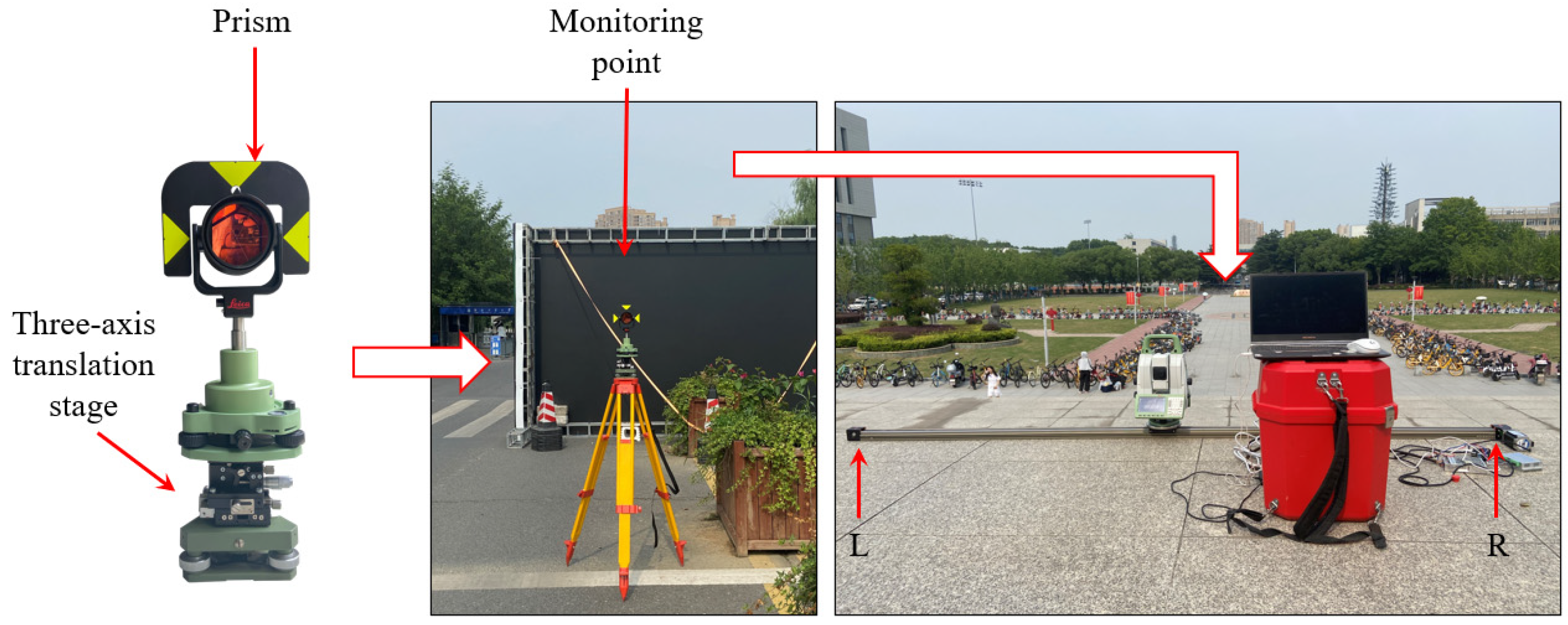

3.3. Practical Test

- (1)

- Manual training: Move the robotic total station to station point and manually sight the reference point and monitoring points to record and store the training data. The approximate coordinates of monitoring points are then calculated and the training data for station point are automatically calculated based on the spatial relationships between the robotic total station and monitoring points.

- (2)

- Automated monitoring: Control the robotic total station to perform automated double-faced observation for the monitoring points located at 150 m and 300 m based on the manually acquired training data at station point . After completing the observation at , move the robotic total station to , driven by the motor, without tracking the prism. Utilize the automatically calculated training data towards to complete automated observation.

- (3)

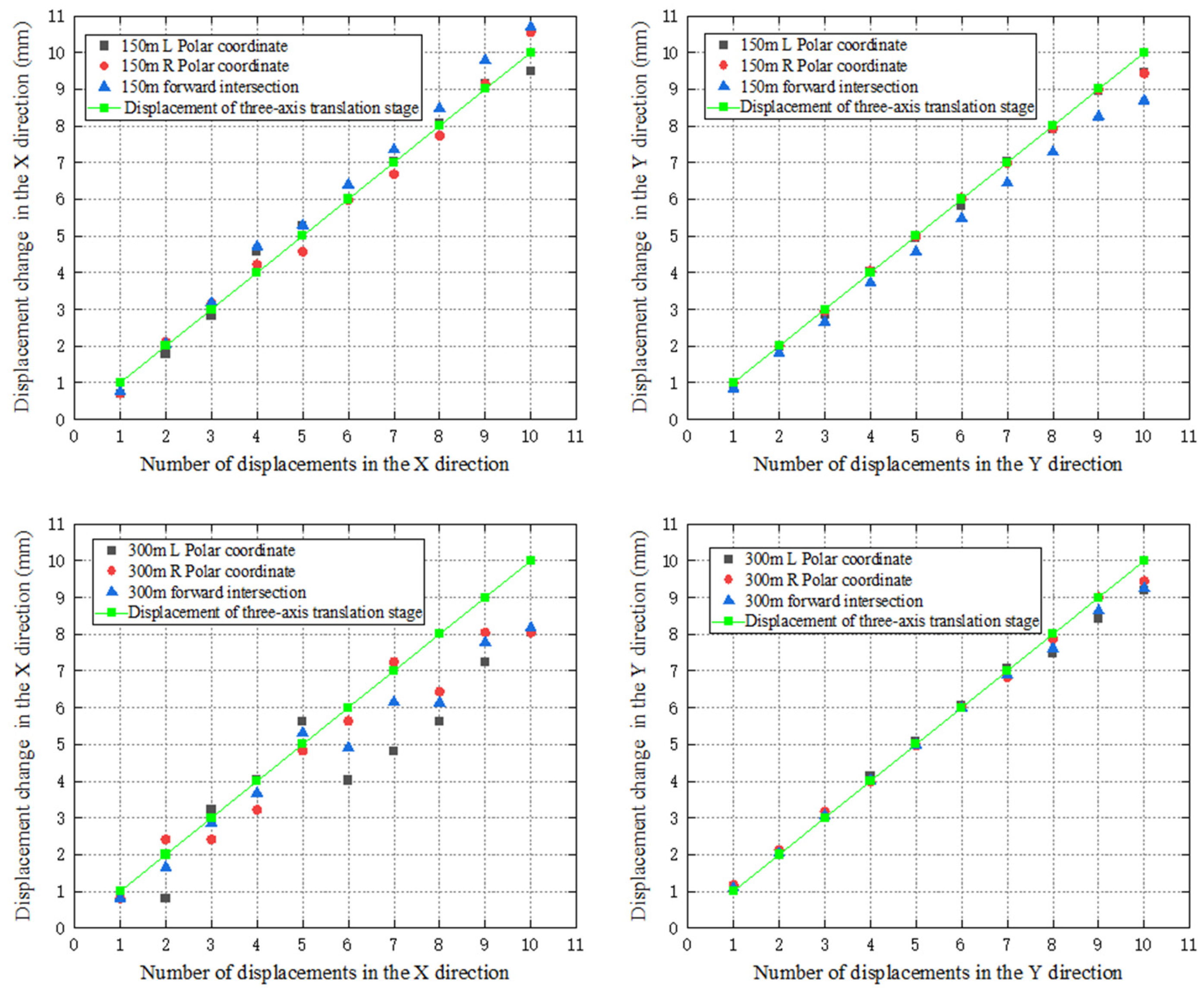

- Displacement simulation and observation: Use the three-axis translation stage to simulate the displacements of the monitoring points and carry out the automated monitoring with the robotic total station. Firstly, move the three-axis translation stages connected to the prisms along the X axis by 1 mm, and perform the automated monitoring in step (2) after each movement until the three-axis translation stages move 10 mm along the X axis. Then restore the three-axis translation stages to initial position and move them gradually along the Y axis by 1 mm until reaching their range of 10 mm. Similarly, perform the automated monitoring in step (2) for each movement.

- (4)

- Data processing: Atmospheric corrections for the distances from each observation are executed according to the weather condition during the test. The coordinates of the monitoring points after each movement are calculated with the polar coordinate system firstly using the observations at and separately. Then, the observations at and are combined and the forward intersection is used to calculate the coordinates of the monitoring points after each movement.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scherer, M.; Lerma, J.L. From the Conventional Total Station to the Prospective Image Assisted Photogrammetric Scanning Total Station: Comprehensive Review. J. Surv. Eng. 2009, 135, 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Paar, R.; Roic, M.; Marendic, A.; Miletic, S. Technological Development and Application of Photo and Video Theodolites. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xiao, H.; Jiang, W.; Bai, W.; Liu, G. Automatic subway tunnel displacement monitoring using robotic total station. Measurement 2020, 151, 107251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrhart, M.; Lienhart, W. Object tracking with robotic total stations: Current technologies and improvements based on image data. J. Appl. Geod. 2017, 11, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, M.; Jiang, R.; Xu, J.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Yu, J.; Su, P.; Liu, C.; Yang, Q.; et al. Structural deformation monitoring during tunnel construction: A review. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2024, 14, 591–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simas, H.; Di Gregorio, R.; Simoni, R.; Gatti, M. Parallel Pointing Systems Suitable for Robotic Total Stations: Selection, Dimensional Synthesis, and Accuracy Analysis. Machines 2024, 12, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Yu, J.; Pan, P.; Xiao, W. Rapid repetition survey of engineering control network based on the concept of Internet of Things. Measurement 2025, 242, 116250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Xie, R.; Liu, C.; Ye, A. Construction and Optimization Method of Large-scale Space Control Field based on Total Station. In Proceedings of the 2022 3rd International Conference on Geology, Mapping and Remote Sensing (ICGMRS), Zhoushan, China, 22–24 April 2022; pp. 139–143. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, F.; Luo, K.; Zhou, W. Measuring Railway Track Irregularities at High Accuracy and Efficiency Based on GNSS/INS/TS Integration. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 15334–15344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitelli, G.; Roncari, G.; Tini, M.A.; Vittuari, L. High-precision topographical methodology for determining height differences when crossing impassable areas. Measurement 2018, 118, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Luo, C.; Jiang, W.; Yu, X.; Wang, P. Using UAVs and robotic total stations in determining height differences when crossing obstacles. Measurement 2022, 188, 110372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Khan, T.U.; Nie, Z.; Yu, Q.; Feng, Z. Calibration and precise orientation determination of a gun barrel for agriculture and forestry work using a high-precision total station. Measurement 2021, 173, 108494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wu, Y.; Li, S.; Sun, Y. A real-time monitoring system for lift-thickness control in highway construction. Autom. Constr. 2016, 63, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.; Boorer, P. Kinematic positioning using a robotic total station as applied to small-scale UAVs. J. Spat. Sci. 2016, 61, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; He, L.; Luo, H. Real-Time Positioning Method for UAVs in Complex Structural Health Monitoring Scenarios. Drones 2023, 7, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Du, W.; Cheng, E.; Yan, Q.; Shen, X. A Noncontact Cutterhead Dynamic Coordinate Measurement Method for Double-Shield TBM Guidance Based on Photographic Imaging. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 71, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, F.; Fu, Y.; Hoang, T.; Mechitov, K.; Spencer, B.F. Estimation of Dynamic Interstory Drift in Buildings Using Wireless Smart Sensors. J. Struct. Eng. 2024, 150, 04024044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, M. Measurement of vibration frequencies of ties in masonry arches by means of a robotic total station. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2022, 21, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehlivan, H. Identification of structural displacements utilizing concurrent robotic total station and GNSS measurements. Smart Struct. Syst. 2022, 30, 411–420. [Google Scholar]

- Zieher, T.; Pfeiffer, J.; Natijne, A.V.; Lindenbergh, R. Integrated Monitoring of a Slowly Moving Landslide Based on Total Station Measurements, Multi-Temporal Terrestrial Laser Scanning and Space-Borne Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Brussels, Belgium, 11–16 July 2021; pp. 942–945. [Google Scholar]

- Emilia, G.D.; Chiominto, L.; Gaspari, A.; Natale, E. After earthquake survey of the structural state of a building by a Robotic Total Station: Metrological aspects. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference (I2MTC), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 22–25 May 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.B.; Chen, J.X.; Xi, W.Z.; Zhao, P.Y.; Qiao, X.; Deng, X.H.; Liu, Q. Analysis of tunnel displacement accuracy with total station. Measurement 2016, 83, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Chen, J.; Xi, W.; Zhao, P.; Li, J.; Qiao, X.; Liu, Q. Application of a Total Station with RDM to Monitor Tunnel Displacement. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2017, 31, 04017030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lienhart, W. Geotechnical monitoring using total stations and laser scanners: Critical aspects and solutions. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2017, 7, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, D.; Chen, J.; Pei, L.; Li, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhang, L. Research and Application of a Smart Monitoring System to Monitor the Deformation of a Dam and a Slope. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 9709417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaioni, M.; Marsella, M.; Crosetto, M.; Tornatore, V.; Wang, J. Geodetic and Remote-Sensing Sensors for Dam Deformation Monitoring. Sensors 2018, 18, 3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsini, A.; Castagnetti, C.; Bertacchini, E.; Rivola, R.; Ronchetti, F.; Capra, A. Integrating airborne and multi-temporal long-range terrestrial laser scanning with total station measurements for mapping and monitoring a compound slow moving rock slide. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2013, 38, 1330–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dematteis, N.; Wrzesniak, A.; Allasia, P.; Bertolo, D.; Giordan, D. Integration of robotic total station and digital image correlation to assess the three-dimensional surface kinematics of a landslide. Eng. Geol. 2022, 303, 106655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Shi, B.; Liu, G.; Ju, S. Accuracy analysis of dam deformation monitoring and correction of refraction with robotic total station. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251281. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Xing, C.; Pan, X. Reservoir Dam Surface Deformation Monitoring by Differential GB-InSAR Based on Image Subsets. Sensors 2020, 20, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Positions on Track (m) | Monitoring Distance (m) | Theoretical Horizontal Angle Readings | Observed Horizontal Angle Readings | Differences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | 10 | 84°17′21.9″ | 83°28′55.0″ | 0°48′26.9″ |

| M | 30 | 88°5′27.1″ | 88°6′55.0″ | 0°1′28.0″ |

| M | 60 | 89°2′42.6″ | 89°6′03.0″ | 0°3′20.4″ |

| M | 100 | 89°25′37.4″ | 89°31′56.5″ | 0°6′19.1″ |

| R | 10 | 78°41′24.2″ | 77°32′41.1″ | 1°8′43.1″ |

| R | 30 | 86°11′09.3″ | 86°11′08.4″ | 0°0′01.0″ |

| R | 60 | 88°5′27.1″ | 88°13′55.0″ | 0°8′27.9″ |

| R | 100 | 88°51′15.3″ | 88°52′00.0″ | 0°0′44.8″ |

| Direction of Displacement | X | Y | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monitoring Methods | Polar Coordinate at | Polar Coordinate at | Forward Intersection | Polar Coordinate at | Polar Coordinate at | Forward Intersection |

| Standard deviation at 150 m(mm) | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.19 |

| Standard deviation at 300 m(mm) | 1.08 | 0.81 | 0.59 | 0.32 | 0.20 | 0.26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jiang, Y.; Gao, H.; Zhou, J. Reliable Automated Displacement Monitoring Using Robotic Total Station Assisted by a Fixed-Length Track. Sensors 2026, 26, 746. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020746

Jiang Y, Gao H, Zhou J. Reliable Automated Displacement Monitoring Using Robotic Total Station Assisted by a Fixed-Length Track. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):746. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020746

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Yunhui, He Gao, and Jianguo Zhou. 2026. "Reliable Automated Displacement Monitoring Using Robotic Total Station Assisted by a Fixed-Length Track" Sensors 26, no. 2: 746. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020746

APA StyleJiang, Y., Gao, H., & Zhou, J. (2026). Reliable Automated Displacement Monitoring Using Robotic Total Station Assisted by a Fixed-Length Track. Sensors, 26(2), 746. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020746