A PI-Dual-STGCN Fault Diagnosis Model Based on the SHAP-LLM Joint Explanation Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

- Constructing a dual-graph structure based on the physical topological relationships and signal similarity derived from sensor distributions significantly reduces reliance on data volume and computational resources for relationship inference while addressing the limitations of pure physical connections in representing implicit dynamic associations.

- 2.

- Designing multi-scale differential layers that fuse differential features with residuals from the original input effectively distinguishes structural evolution patterns across different scales, mitigating the over-smoothing issue commonly observed in graph neural networks.

- 3.

- The SHAP framework based on Deep Explainer is used to quantify the impact of diagnostic model input features on specific prediction results, achieving a dual visual interpretation of the model at both the global and local levels. Building on this, an innovative quantitative evaluation metric system for SHAP interpreters is proposed, addressing the critical issue of the lack of objective assessment standards for interpretation results in existing methods.

- 4.

- Combining SHAP quantitative information with expert knowledge and fault diagnosis results, a private knowledge base for fault diagnosis is constructed. Using RAG retrieval enhancement technology and feature prompting engineering, high-dimensional SHAP values are mapped into structured semantic inputs to drive LLMs to generate credible text explanations aligned with domain knowledge, establishing a domain-knowledge-guided text generation mechanism for fault diagnosis explanations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The PI-Dual-STGCN Fault Diagnosis Framework

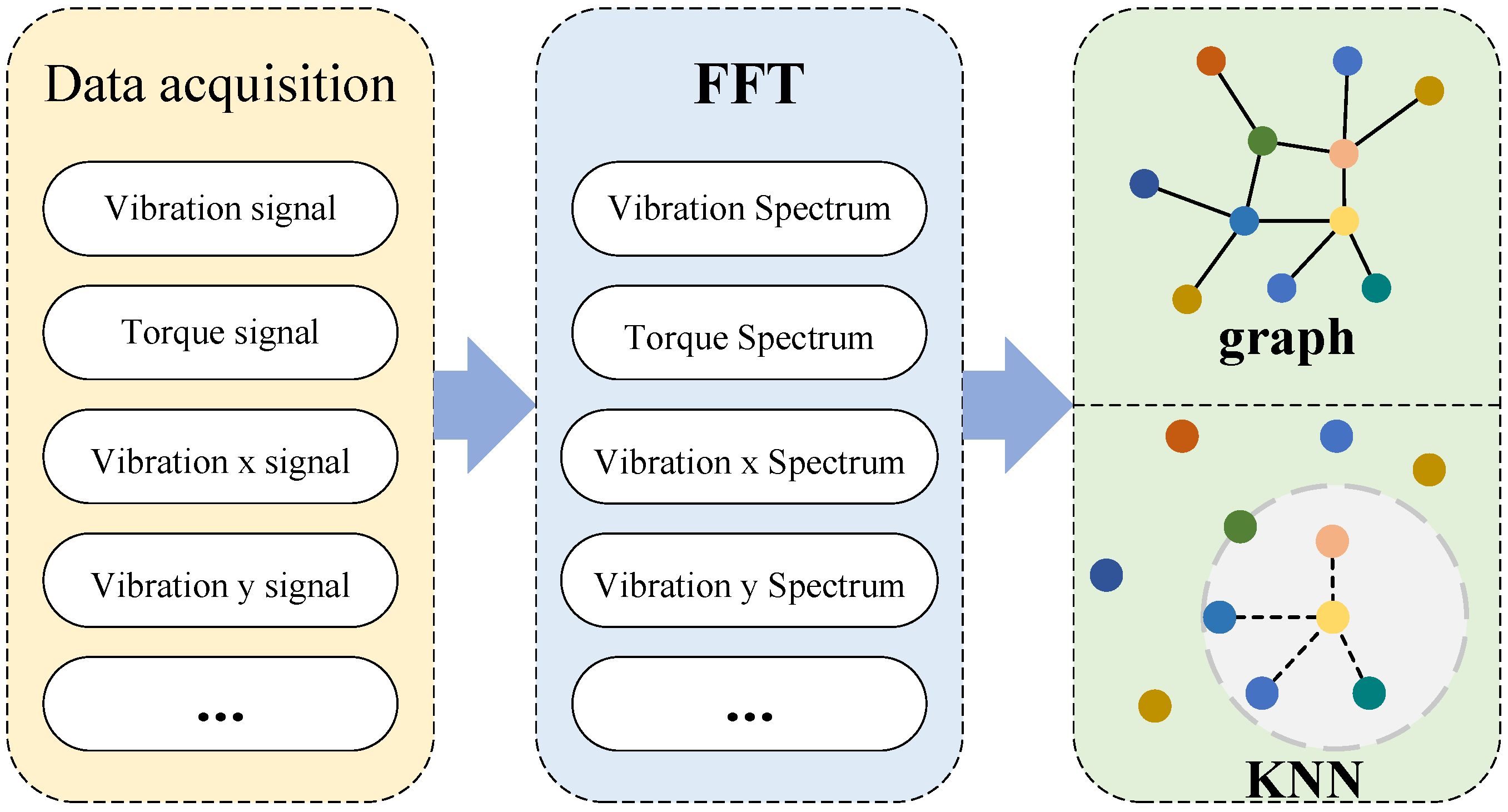

2.1.1. Dual-Graph Construction

Physical Information Graph Construction

Signal Similarity Graph Construction

2.1.2. Differential Layer

2.2. The SHAP-LLM Joint Explanation Framework

2.2.1. SHAP Interpretation Algorithm and Comprehensive Evaluation Framework

| Algorithm 1 Hierarchical Background Sampling for Deep SHAP on Spatiotemporal Graph Models | |

| Require: Training dataset with samples | |

| Require: Background dataset size | |

| Require: Number of fault classes | |

| Require: Random seed for reproducibility | |

| Ensure: Background dataset for SHAP explanation | |

| 1: Calculate target samples per class: | |

| 2: Initialize class_indices as empty dictionary | |

| ▹ Step 1: Organize samples by class | |

| 3: for to do | |

| 4: | |

| 5: class_indices class_indices | |

| 6: end for | |

| ▹ Step 2: Stratified sampling | |

| 7: | |

| 8: for to do | |

| 9: class_indices | |

| 10: if then | |

| 11: | |

| 12: else | |

| 13: | ▹ Use all available samples |

| 14: end if | |

| 15: | |

| 16: end for | |

| ▹ Step 3: Load and preprocess samples | |

| 17: | |

| 18: for each index do | |

| 19: | |

| 20: | ▹ Preprocess for model input compatibility: |

| 21: | ▹ To shape |

| 22: sensor_data | |

| 23: | ▹ To shape |

| 24: | |

| 25: end for | |

| 26: return | |

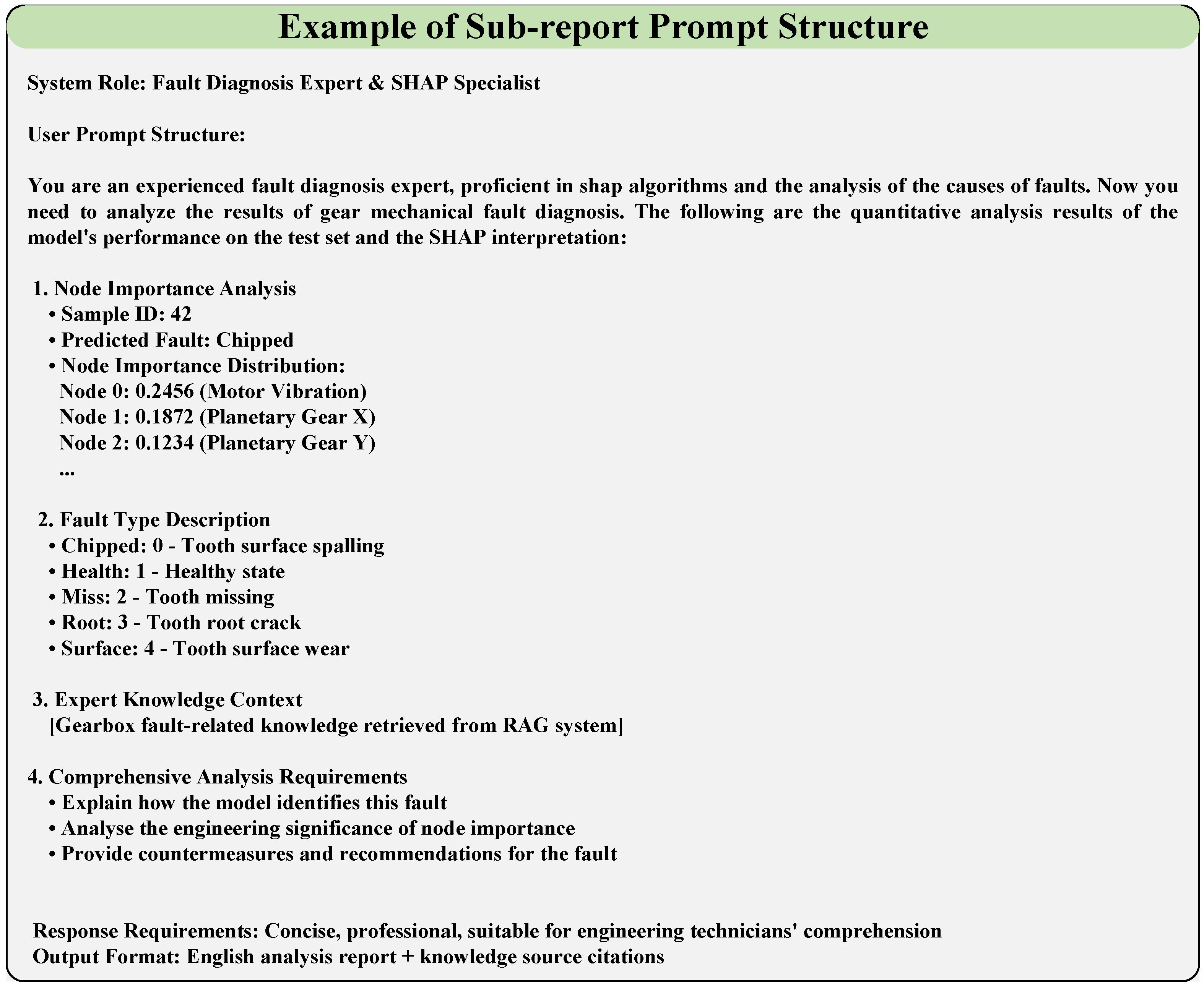

2.2.2. RAG-Based LLM Explanation Method

3. Experimental Verification of Fault Diagnosis Algorithms

3.1. Experimental Setup and Evaluation Criteria

3.2. Results and Analysis

3.3. Ablation Experiment

- Average Inter-layer Node Embedding Similarity: Mean cosine similarity of node features between consecutive model layers (higher values indicate more severe feature homogenization, i.e., over-smoothing);

- Intra-/Inter-Class Distance Ratio: Ratio of mean intra-class feature distance to mean inter-class feature distance (lower values reflect better separability of fault class representations);

- SHAP Score Stability: Standard deviation of SHAP feature importance scores across 100 test samples (smaller values correspond to more stable model decision explanations).

- The average inter-layer node embedding similarity rises from 0.63 (full model) to 0.71 (an increase of 12.7%), which directly indicates more severe feature homogenization—the core manifestation of over-smoothing.

- The intra-/inter-class distance ratio increases from 0.47 to 0.51 (an 8.2% rise), meaning the separability of feature representations between different fault classes is weakened.

- The SHAP score standard deviation expands from 0.08 to 0.10 (a 25.0% growth), reflecting that the model’s decision explanation logic becomes less consistent across test samples.

4. Experimental Verification of Model Interpretability Solutions

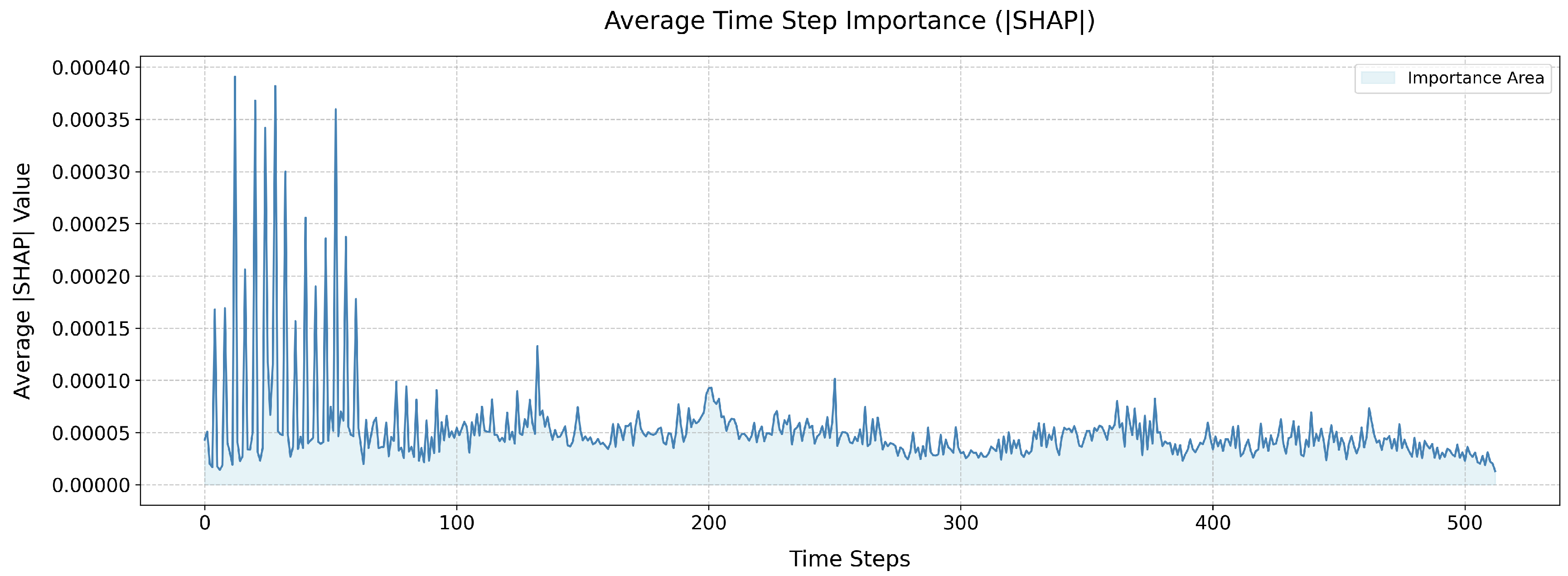

4.1. Visual Interpretation of Model Diagnostics Based on SHAP

4.2. Model Diagnosis Text Explanation Based on RAG and LLM

5. Conclusions

- While the Table 3 has confirmed the effectiveness of the designed physical prior graph (model performance decreases notably when this component is removed), this study only adopted one specific construction strategy—based on the gearbox’s motion transmission paths and component co-location—for the physical prior graph. Alternative, potentially more optimal construction schemes (e.g., incorporating finer-grained physical constraints such as gear meshing stiffness) that could enhance the graph’s physical interpretability and the model’s diagnostic performance remain unexplored.

- Due to manuscript space constraints, validation of the framework was not extended to scenarios representative of practical industrial deployments, including sensor re-layout, partial missing sensors, or cross-platform sensor configurations. The robustness of the physical prior graph (and the overall PI-Dual-STGCN model) under these non-ideal sensing conditions is thus untested.

- Although the SEU gearbox dataset used in the experiment has five types of faults, the fault data is relatively independent and does not include fault samples where multiple faults occur simultaneously. Therefore, the performance of the PI-Dual-STGCN model and the SHAP-LLM framework in the compound fault scenario (where multiple defects exist in the gearbox) has not yet been verified. This limits the direct application value of the proposed method in real industrial scenarios—where the phenomenon of multi-defect degradation is widespread.

- The current SHAP-LLM joint interpretation only focuses on data-level feature importance, and a correspondence table linking fault mechanisms (e.g., gear meshing anomalies), observable physical features (e.g., meshing frequencies, sidebands, envelope features), and SHAP high-importance regions has not been established. Additionally, we did not conduct cross-validation with alternative XAI methods (e.g., LIME), which restricts verification of the interpretability results’ physical rationality, consistency, and stability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, C.; Shen, Q.; Wang, L.; Qin, W.; Xie, M. A new adaptive interpretable fault diagnosis model for complex system based on belief rule base. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 3529111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, A.; Zeng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, P.; Li, J.; Gao, M. A fault diagnosis analysis of afterburner failure of aeroengine based on fault tree. Processes 2023, 11, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Lei, Y.; Qi, G.; Chai, Y.; Mazur, N.; An, Y.; Huang, X. A review of the application of deep learning in intelligent fault diagnosis of rotating machinery. Measurement 2023, 206, 112346. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Qi, L.; Shi, J.; Xiao, H.; Da, B.; Tang, R.; Zuo, D. Study on Few-Shot Fault Diagnosis Method for Marine Fuel Systems Based on DT-SViT-KNN. Sensors 2024, 25, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Luo, H.; Yin, S. A novel data augmentation approach to fault diagnosis with class-imbalance problem. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 243, 109832. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Ma, J.; Li, T. Diagnosisformer: An efficient rolling bearing fault diagnosis method based on improved transformer. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 124, 106507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, H.; Dai, L.; Huang, B. A parallel deep neural network for intelligent fault diagnosis of drilling pumps. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Qi, L.; Ye, S.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, H.; Li, S. Research on Fault Diagnosis Algorithm of Ship Electric Propulsion Motor. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Qi, L.; Sun, J.; Jiang, C.; Su, J.; Shu, W. Fault Diagnosis Technology for Ship Electrical Power System. Energies 2022, 15, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melluso, F.; Spirto, M.; Nicolella, A.; Malfi, P.; Tordela, C.; Cosenza, C.; Savino, S.; Niola, V. Torque fault signal extraction in hybrid electric powertrains through a wavelet-supported processing of residuals. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2026, 242, 113652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, T.; He, J.; Liu, T. An Interpretable Wavelet Kolmogorov–Arnold Convolutional LSTM for Spatial-temporal Feature Extraction and Intelligent Fault Diagnosis. J. Dyn. Monit. Diagn. 2025, 4, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misbah, I.; Lee, C.; Keung, K.L. Fault diagnosis in rotating machines based on transfer learning: Literature review. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 283, 111158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Qi, L.; Ye, S.; Li, C.; Jiang, C.; Ni, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Tong, Z.; Fei, S.; Tang, R.; et al. Intelligent Fault Diagnosis of Rolling Bearings Based on Digital Twin and Multi-Scale CNN-AT-BiGRU Model. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gompel, J.; Spina, D.; Develder, C. Cost-effective fault diagnosis of nearby photovoltaic systems using graph neural networks. Energy 2023, 266, 126444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Da, B.; Qi, L.; Xiao, H.; Li, S. Condition Monitoring of Marine Diesel Lubrication System Based on an Optimized Random Singular Value Decomposition Model. Machines 2024, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, W. Interpretability of deep convolutional neural networks on rolling bearing fault diagnosis. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2022, 33, 055005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, A.B.; Díaz-Rodríguez, N.; Del Ser, J.; Bennetot, A.; Tabik, S.; Barbado, A.; García, S.; Gil-López, S.; Molina, D.; Benjamins, R.; et al. Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI): Concepts, taxonomies, opportunities and challenges toward responsible AI. Inf. Fusion 2020, 58, 82–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.; Peng, W.; Feng, G.; Pan, M. Bayesian deep learning for fault diagnosis of induction motors with reduced data reliance and improved interpretability. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2025, 40, 2155–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Qi, L.; Shi, J.; Li, S.; Tang, R.; Zuo, D.; Da, B. Reliability Assessment of Ship Lubricating Oil Systems Through Improved Dynamic Bayesian Networks and Multi-Source Data Fusion. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.; Mubarak, A.; Waseem, S. Application of physics-informed neural networks in fault diagnosis and fault-tolerant control design for electric vehicles: A review. Measurement 2025, 246, 116728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cação, J.; Santos, J.; Antunes, M. Explainable AI for industrial fault diagnosis: A systematic review. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2025, 47, 100905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Gao, X.; Gao, H.; Han, H.; Qi, Y.; Han, H. A zero-shot fault diagnosis framework for chillers based on sentence-level text attributes. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 2878–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Chen, Q.; Yao, J.; He, Q.; Peng, Z. An interpretable deep feature aggregation framework for machinery incremental fault diagnosis. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 65, 103189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Gu, K.; Jiang, H.; Liang, W.; Zhong, S. Partial fault diagnosis for rolling bearing based on interpretable partial domain adaptation network. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 3541815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jia, Z.; Liu, Z.; Shao, H.; Zhao, W.; Liu, Z.; Wang, B. Interpretable intelligent fault diagnosis strategy for fixed-wing UAV elevator fault diagnosis based on improved cross entropy loss. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 076110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Li, M.; Wu, Z.; Gao, K.; Wang, F. Feature selection and interpretability analysis of compound faults in rolling bearings based on the causal feature weighted network. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 086201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Red Hook, NY, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- Vimbi, V.; Shaffi, N.; Mahmud, M. Interpreting artificial intelligence models: A systematic review on the application of LIME and SHAP in Alzheimer’s disease detection. Brain Inform. 2024, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaif, K.M.; Albeshri, A.A.; Khemakhem, M.A.; Eassa, F.E. Multimodal large language model-based fault detection and diagnosis in context of Industry 4.0. Electronics 2024, 13, 4912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Zhang, S.; Fu, S.; Liu, Y. FD-LLM: Large language model for fault diagnosis of complex equipment. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 65, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zheng, S.; Yang, Z.; Pan, H.; Hong, J. A knowledge-graph enhanced large language model-based fault diagnostic reasoning and maintenance decision support pipeline towards industry 5.0. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2025, 63, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, T.; Yang, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhai, W. DiagLLM: Multimodal reasoning with large language model for explainable bearing fault diagnosis. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2025, 68, 160103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, B.; Gao, D. Bearing fault diagnosis based on multi-scale CNN and LSTM model. J. Intell. Manuf. 2021, 32, 971–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veličković, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Liò, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph attention networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.10903. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Cao, H.; Xu, H.; Liu, H. A gated graph convolutional network with multi-sensor signals for remaining useful life prediction. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 252, 109340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, C.; Yan, R. Hierarchical attention graph convolutional network to fuse multi-sensor signals for remaining useful life prediction. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 215, 107878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Xu, W.; Bi, F.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, L.; Yi, L. Multi-scale neighborhood query graph convolutional network for multi-defect location in CFRP laminates. Comput. Ind. 2023, 153, 104015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, C.; Yan, R.; Chen, X. Multireceptive field graph convolutional networks for machine fault diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 12739–12749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, M.; Bo, D.; Cui, P.; Shi, C.; Pei, J. AM-GCN: Adaptive multi-channel graph convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining (KDD), Virtual Event, 6–10 July 2020; pp. 1243–1253. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, S.; McAleer, S.; Yan, R.; Baldi, P. Highly accurate machine fault diagnosis using deep transfer learning. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2019, 15, 2446–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Parameter/Component | Value/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Data Preprocessing | Window size | 1024 sampling points |

| Sliding step size | 1024 sampling points (no overlap between samples) | |

| FFT output dimension | 513 frequency-domain points | |

| Data split | 80% training/20% testing (stratified random sampling) | |

| Normalization method | Min–Max normalization | |

| Hyperparameters | Difference layers | 4 |

| Node features | 5 | |

| Number of classes | 5 | |

| Number of nodes | 8 | |

| Learning rate | ||

| Weight decay | ||

| Batch size | 64 | |

| Number of epochs | 80 | |

| Optimizer | Adam | |

| Loss function | Cross-entropy | |

| Background dataset size | 180 | |

| Number of explanation samples | 10 | |

| Background sampling strategy | Hierarchical (Algorithm 1) | |

| Hardware Specifications | CPU | Intel i7-9750H (2.6 GHz, 6 cores) |

| GPU | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2070 (8 GB VRAM) | |

| RAM | 16 GB DDR4 | |

| Software Environment | Operating system | Ubuntu 20.04 LTS |

| Python version | 3.8.10 | |

| PyTorch version | 1.9.0 | |

| CUDA version | 11.4 |

| Models | Acc (Mean ± SD,%) | P (Mean ± SD,%) | R (Mean ± SD,%) | F1 (Mean ± SD,%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCN-LSTM | 95.87 ± 0.62 | 96.10 ± 0.58 | 94.85 ± 0.67 | 95.47 ± 0.60 |

| GAT | 96.22 ± 0.51 | 97.85 ± 0.47 | 97.15 ± 0.53 | 97.50 ± 0.49 |

| GGCN | 98.15 ± 0.38 | 98.30 ± 0.35 | 97.85 ± 0.41 | 98.07 ± 0.37 |

| HAGCN | 98.34 ± 0.32 | 98.45 ± 0.29 | 98.10 ± 0.34 | 98.27 ± 0.30 |

| AM-GCN | 99.05 ± 0.18 | 99.12 ± 0.16 | 98.95 ± 0.20 | 99.03 ± 0.17 |

| MNQGN | 97.82 ± 0.43 | 98.05 ± 0.40 | 97.25 ± 0.46 | 97.64 ± 0.42 |

| MRF-GCN | 98.76 ± 0.27 | 98.85 ± 0.25 | 98.60 ± 0.29 | 98.75 ± 0.26 |

| PI-Dual-STGCN (Ours) | 99.22 ± 0.09 | 99.22 ± 0.08 | 99.2 ± 0.10 | 99.22 ± 0.08 |

| Variant Models | Acc (Mean ± SD,%) | P (Mean ± SD,%) | R(Mean ± SD,%) | F1 (Mean ± SD,%) | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Model (Ours) | 99.22 ± 0.09 | 99.22 ± 0.08 | 99.20 ± 0.10 | 99.22 ± 0.08 | - |

| w/o PI Graph | 98.65 ± 0.21 | 98.70 ± 0.20 | 98.52 ± 0.22 | 98.61 ± 0.21 | −0.61 |

| w/o Signal Graph | 98.71 ± 0.19 | 98.75 ± 0.18 | 98.63 ± 0.20 | 98.68 ± 0.19 | −0.54 |

| Single-Graph | 97.95 ± 0.33 | 98.00 ± 0.31 | 97.82 ± 0.35 | 97.91 ± 0.33 | −1.31 |

| w/o MS-Diff | 98.88 ± 0.15 | 98.90 ± 0.14 | 98.82 ± 0.16 | 98.86 ± 0.15 | −0.36 |

| Variant Models | Average Inter-Layer Node Embedding Similarity | Intra-/Inter-Class Distance Ratio | SHAP Score Stability (Standard Deviation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Model (Ours) | 0.63 | 0.47 | 0.08 |

| w/o MS-Diff | 0.71 | 0.51 | 0.10 |

| Evaluation Indicator Name | Indicator Value |

|---|---|

| Node importance consistency | 0.9666 |

| Time step importance consistency | 0.9994 |

| Interpretation stability | 0.9996 |

| Interpretation rationality | 0.8008 |

| Category discrimination | 1.4624 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhao, Z.; Ye, S.; Qi, L.; Ni, H.; Fei, S.; Tong, Z. A PI-Dual-STGCN Fault Diagnosis Model Based on the SHAP-LLM Joint Explanation Framework. Sensors 2026, 26, 723. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020723

Zhao Z, Ye S, Qi L, Ni H, Fei S, Tong Z. A PI-Dual-STGCN Fault Diagnosis Model Based on the SHAP-LLM Joint Explanation Framework. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):723. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020723

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Zheng, Shuxia Ye, Liang Qi, Hao Ni, Siyu Fei, and Zhe Tong. 2026. "A PI-Dual-STGCN Fault Diagnosis Model Based on the SHAP-LLM Joint Explanation Framework" Sensors 26, no. 2: 723. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020723

APA StyleZhao, Z., Ye, S., Qi, L., Ni, H., Fei, S., & Tong, Z. (2026). A PI-Dual-STGCN Fault Diagnosis Model Based on the SHAP-LLM Joint Explanation Framework. Sensors, 26(2), 723. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020723