SeADL: Self-Adaptive Deep Learning for Real-Time Marine Visibility Forecasting Using Multi-Source Sensor Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We propose a self-adaptive deep learning framework for real-time marine visibility forecasting that operates under dynamic and data-sparse oceanic conditions.

- We introduce a clustered modeling architecture that simultaneously forecasts visibility at a vessel’s current location and at multiple nearby remote locations.

- We develop an online, sequence-based training strategy using LSTM networks to capture both short-term fluctuations and longer-term visibility patterns.

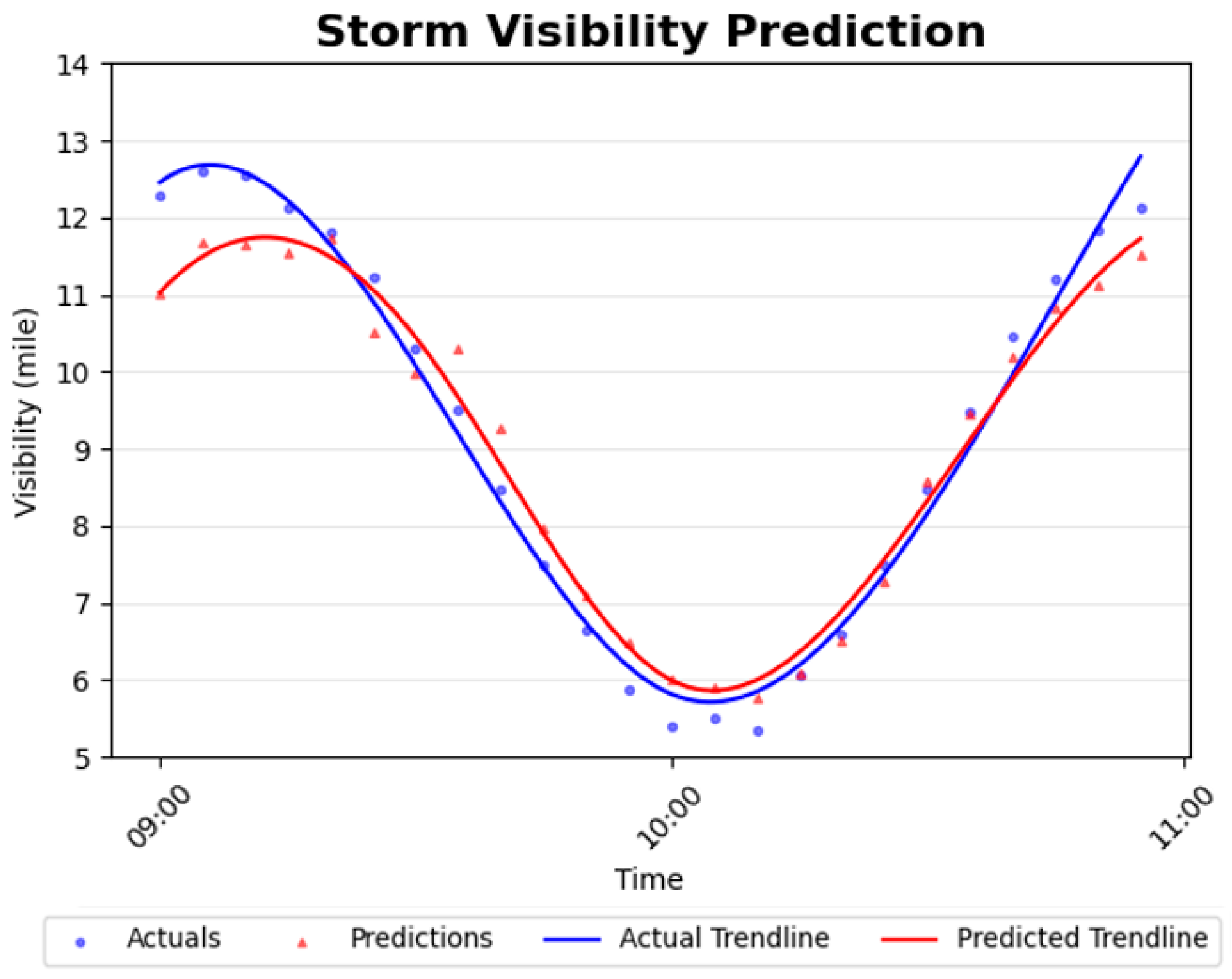

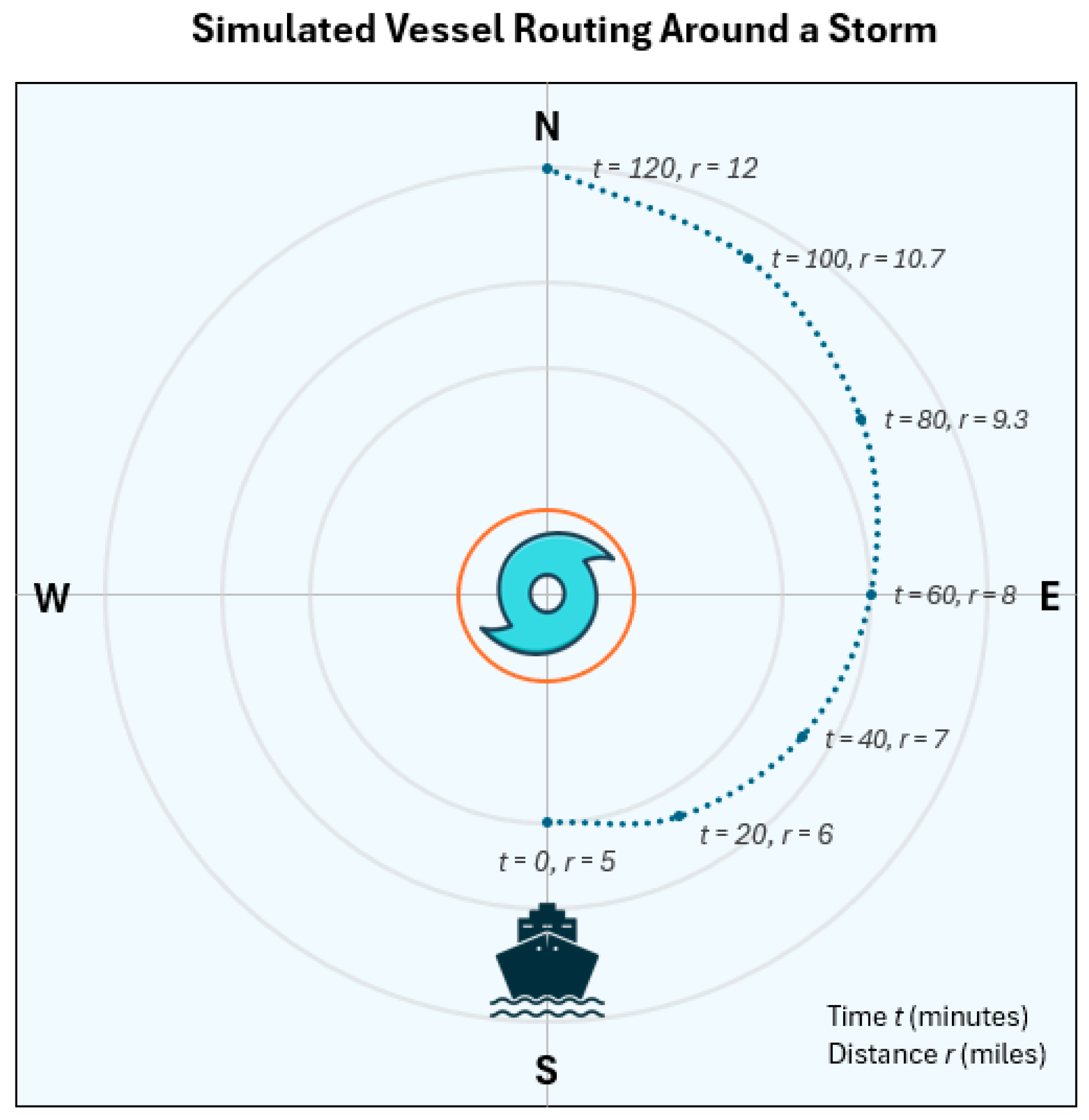

- We demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed framework through realistic diurnal and storm-driven case studies.

2. Related Work

3. Self-Adaptive Deep Learning for Marine Visibility Forecasting

3.1. Problem Formulation and Data Sources

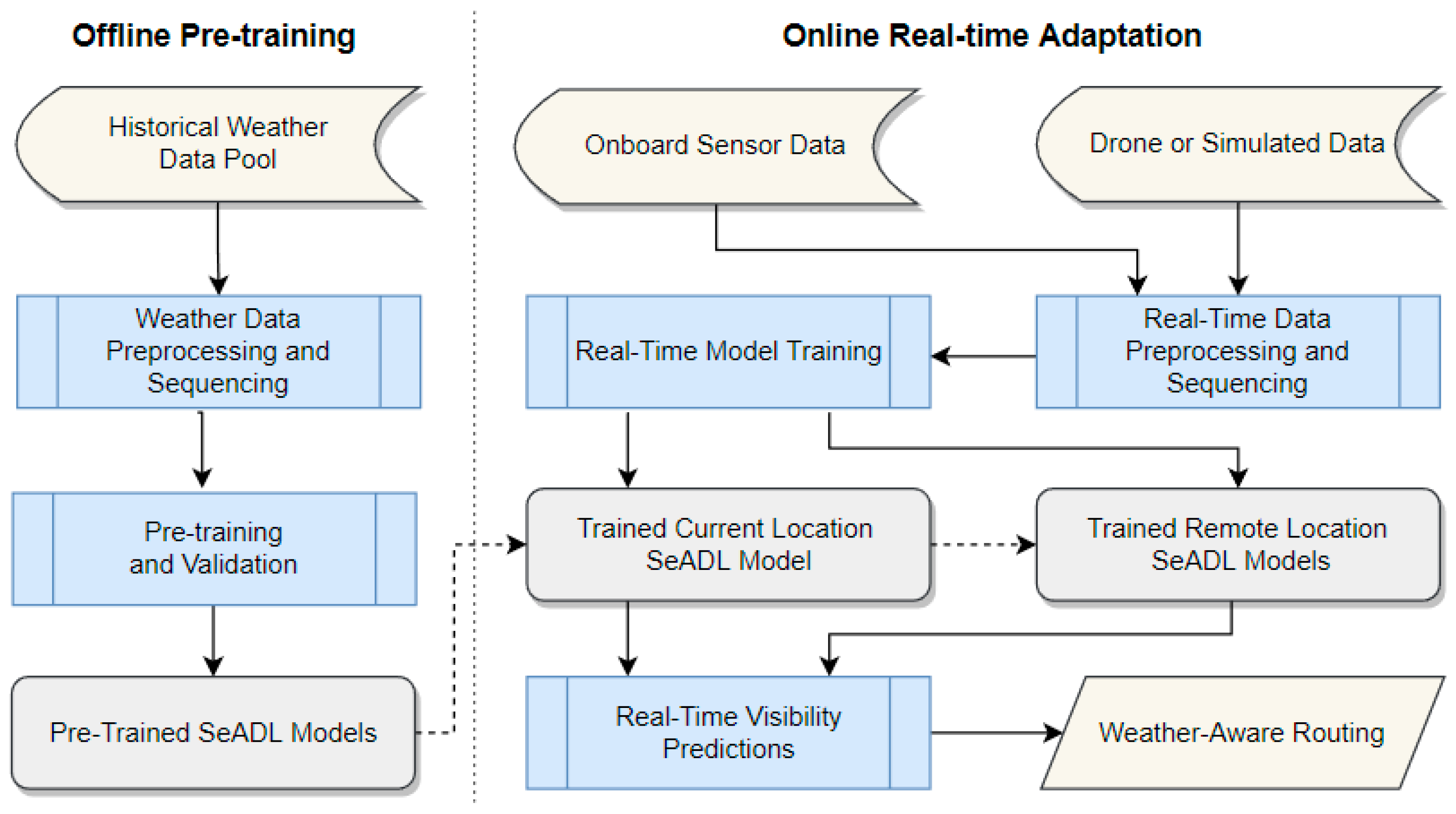

3.2. A Framework for Real-Time Visibility Prediction

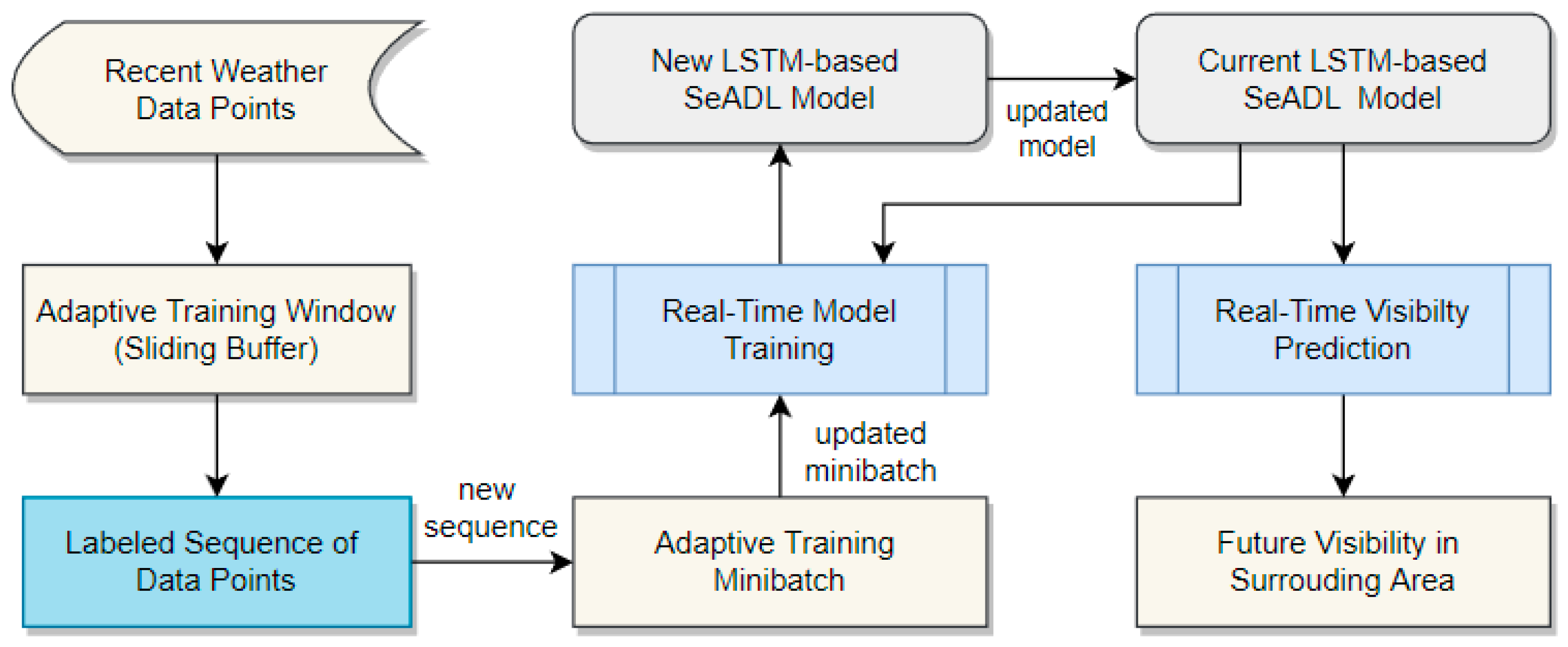

3.3. Real-Time Updating of LSTM-Based SeADL Models

4. Time-Series Dataset Design and Adaptive Training Minibatch

4.1. Temporal Structuring of Time-Series Data

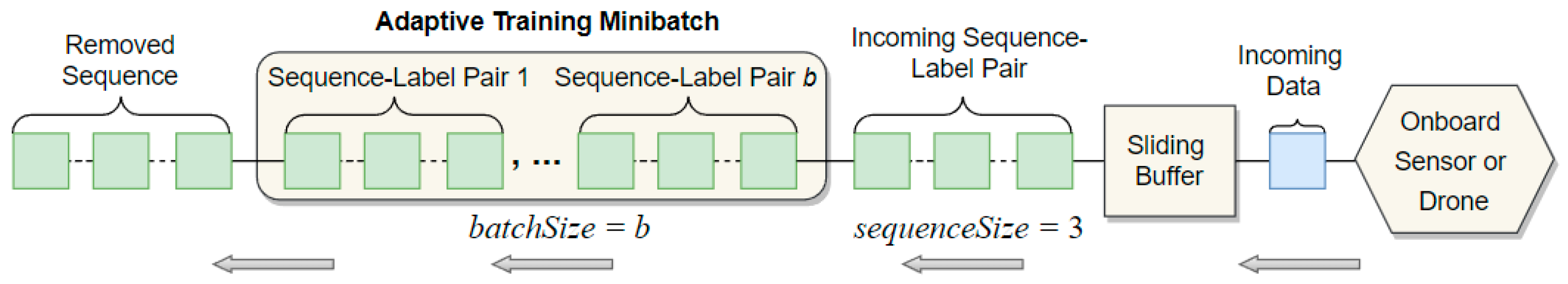

4.2. Adaptive Training Minibatch Construction for Real-Time LSTM Training

| Algorithm 1. Updating the Adaptive Training Minibatch |

| Input: Most recent feature vector observed at time t, including visibility measurement v(t); sequence length τ; minibatch size b; prediction horizon h; sliding buffer B Output: Updated adaptive training minibatch Γ |

| 1. if sliding buffer B is empty then // first invocation 2. Initialize sliding buffer B using the most recent historical data points 3. Initialize adaptive training minibatch Γ with b historical sequences of length τ, each paired with its corresponding visibility value 4. Append feature vector to the end of B 5. Remove the oldest feature vector from B 6. Let //s is the most recent time for which the -ahead label is now available 7. Construct a training sequence from the oldest τ feature vectors in B 8. Pair with visibility label = v(t) // ( is the latest sequence-label pair 9. Append the new pair ( to the end of Γ 10. Remove the oldest sequence-label pair from Γ to maintain size b 11. return updated Γ |

4.3. Sequence Length and Minibatch Size for Diurnal and Storm Models

5. Real-Time Training of SeADL Models for Visibility Forecasting

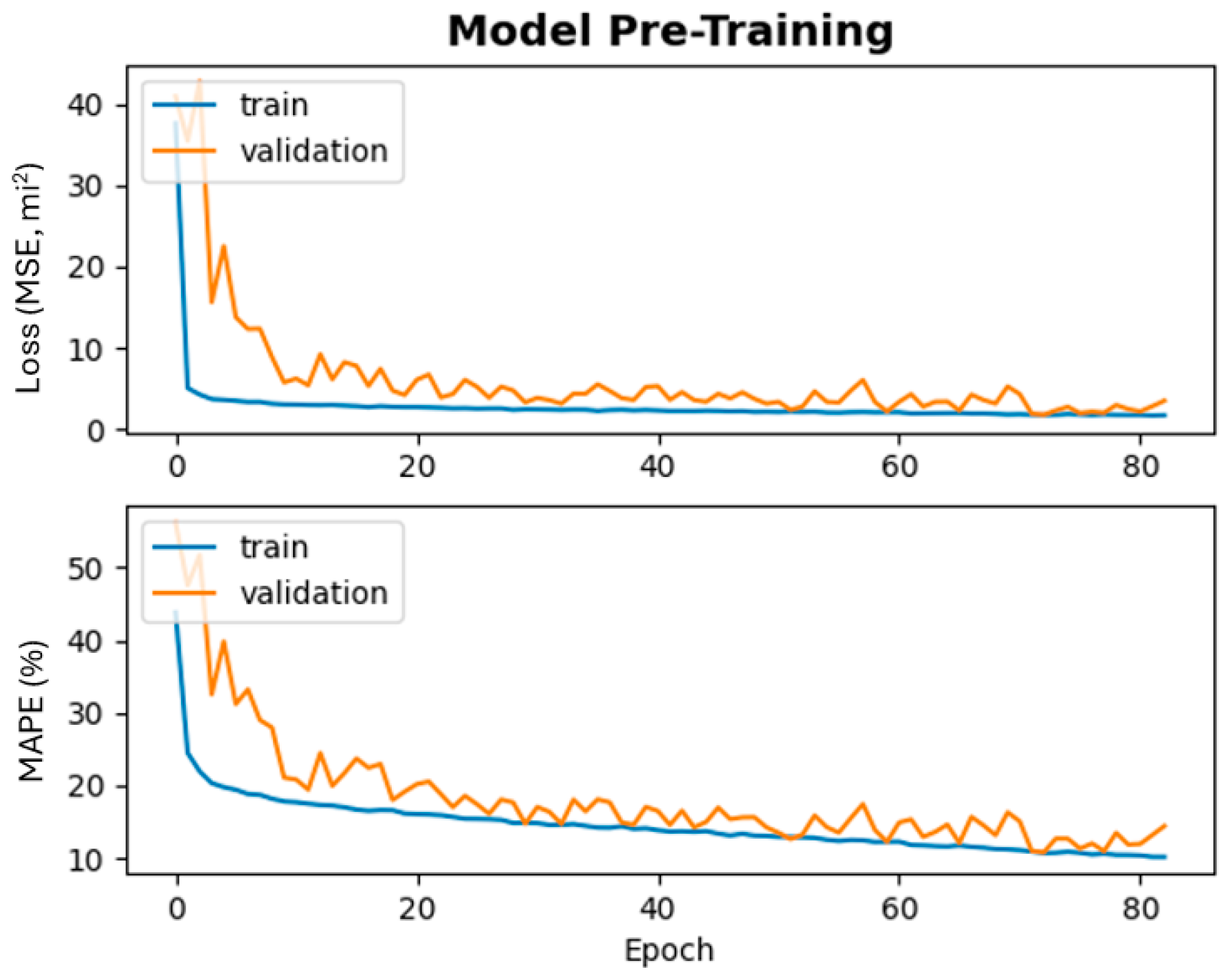

5.1. Tuning of LSTM Hyperparameters

5.2. SeADL Model Pre-Training

5.3. Real-Time Training of SeADL and Visibility Forecasting

| Algorithm 2. Real-Time Training and Prediction for a Single SeADL Model |

| Input: SeADL model Φ with sequence length τ, minibatch size b, and maximum minibatch epochs ; prediction horizon h; sampling rate r (where r divides h) Output: Updated SeADL model Φ and predicted visibility |

| 1. Compute prediction offset 2. if sliding buffer B does not exist then 3. Create an empty buffer B of size τ + pos for Φ 4. Collect features from Φ’s active location (current or remote) 5. Invoke Algorithm 1 to construct an adaptive training minibatch ΓΦ with |ΓΦ | = b 6. Initialize epoch count and previous average training accuracy 7. while do 8. Initialize accumulated training accuracy 9. for each sequence-label pair α in ΓΦ do 10. Fine-tune model Φ on α using backpropagation 11. Compute training accuracy using Equation (5) 12. 13. Compute average training accuracy 14. if and then break 15. ; 16. Extract prediction sequence of length τ from B 17. Generate a visibility forecast for Φ’s active location 18. return updated SeADL model Φ and predicted visibility |

6. Case Studies

6.1. Experimental Setup and Dataset Descriptions

6.2. Normal Weather with Day-Night Cycle

6.3. Forecasting Visibility Under a Simulated Storm Scenario

6.4. Visibility-Based Navigation of a Moving Vessel Around a Nearby Storm

6.5. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DCNN | Deep Convolutional Neural Network |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| NOAA | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| RT-SAC | Real-Time Self-Adaptive Classifier |

| SeADL | Self-Adaptive Deep Learning |

References

- Cahir, J. History of Weather Forecasting, Britannica. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/science/weather-forecasting/History-of-weather-forecasting (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, Working Group 1. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/ (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Song, M.; Wang, J.; Li, R. The importance of weather factors in the resilience of airport flight operations based on Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KANs). Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Abdel-Aty, M.; Shi, Q.; Yu, R. Assessing the impact of reduced visibility on traffic crash risk using microscopic data and surrogate safety measures. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2017, 74, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Li, R.; Li, C.; Yang, B.; Li, Y.; Yu, Q.; Geng, X.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, K.; Wen, J. Review of ship navigation safety in fog. J. Navig. 2024, 77, 436–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Sun, H. Safety measures and practice of ship navigation in restricted visibility base on collision case study. Am. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2023, 8, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD. Review of Maritime Transport 2021, UN Trade & Development. Available online: https://unctad.org/publication/review-maritime-transport-2021 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Jonnalagadda, J.; Hashemi, M. Forecasting atmospheric visibility using auto regressive recurrent neural network. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 21st International Conference on Information Reuse and Integration for Data Science (IRI), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 11–13 August 2020; pp. 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Cui, J.; Huang, M. Extreme weather prediction for highways based on LSTM-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2023 5th International Conference on Applied Machine Learning (ICAML), Dalian, China, 21–23 July 2023; pp. 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultepe, E.; Wang, S.; Blomquist, B.; Harindra, F.; Kreidl, O.P.; Delene, D.J.; Gultepe, I. Generative nowcasting of marine fog visibility in the grand banks area and sable island in Canada. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.06800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.-H.; Park, S.-K.; Park, S.-H.; Kwon, K.-W.; Im, T.-H. RDCP: A real time sea fog intensity and visibility estimation algorithm. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 12, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA. What Is an Operational Forecast System? National Ocean Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Available online: https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/ofs.html (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Girard, W.; Xu, H.; Yan, D. Real-time forecasting of marine visibility with self-adaptive deep learning. In Proceedings of the 4th IEEE International Conference on Computing and Machine Intelligence (ICMI 2025), Mt. Pleasant, MI, USA, 5–6 April 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aty, M.; Ekram, A.-A.; Huang, H.; Choi, K. A study on crashes related to visibility obstruction due to fog and smoke. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2011, 43, 1730–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, W.; Gong, B.; Mao, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; He, J.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, H. A study on short-term visibility prediction model in Jiangsu province based on random forest. In Proceedings of the 2024 9th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Big Data Analytics (ICCCBDA 2024), Chengdu, China, 25–27 April 2024; pp. 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabhade, A.; Roy, S.; Moustafa, M.S.; Mohamed, S.A.; El Gendy, R.; Barma, S. Extreme weather event (cyclone) detection in India using advanced deep learning techniques. In Proceedings of the 2021 9th International Conference on Orange Technology (ICOT), Tainan, Taiwan, 16–17 December 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttil, N.; Chau, K.-W. Machine-learning paradigms for selecting ecologically significant input variables. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2007, 20, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-S.; Lee, J.-B.; Roh, M.-I.; Han, K.-M.; Lee, G.-H. Prediction of ocean weather based on denoising autoencoder and convolutional LSTM. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krestenitis, M.; Orfanidis, G.; Ioannidis, K.; Avgerinakis, K.; Vrochidis, S.; Kompatsiaris, I. Oil spill identification from satellite images using deep neural networks. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, J.J.; Lim, K.H.; Pang, P.K. Deep learning super resolution of sea surface temperature on south China sea. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Green Energy, Computing and Sustainable Technology (GECOST), Miri, Malaysia, 26–28 October 2022; pp. 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakirci, M. Advanced ship detection and ocean monitoring with satellite imagery and deep learning for marine science applications. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2025, 81, 103975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, M.; Ahmad, G. Deep learning based real time face recognition for university attendance system. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Symposium on Devices, Circuits and Systems (ISDCS), Higashihiroshima, Japan, 29–31 May 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, B.J.; Xu, H.; Valova, I. A real-time self-adaptive classifier for identifying suspicious bidders in online auctions. Comput. J. 2012, 56, 646–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, W.; Xu, H.; Yan, D. Real-time evolving deep learning models for predicting hydropower generation. In Proceedings of the 3rd IEEE International Conference on Computing and Machine Intelligence (ICMI 2024), Mt. Pleasant, MI, USA, 13–14 April 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, I.O.; Rossi, R.A.; Barrow, J.; Tanjim, M.; Kim, S.; Dernoncourt, F.; Yu, T.; Zhang, R.; Ahmed, N.K. Bias and fairness in large language models: A survey. Comput. Linguist. 2024, 50, 1097–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Muñoz, I.; Montejo-Ráez, A.; Martínez-Santiago, F.; Ureña-López, L.A. A survey on bias in deep NLP. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardi, G. On the implicit bias in deep-learning algorithms. Commun. ACM 2023, 66, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA. International Comprehensive Ocean-Atmosphere Data Set (ICOADS), National Centers for Environmental Information. Available online: https://icoads.noaa.gov/ (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Inoue, J.; Sato, K. Challenges in detecting clouds in polar regions using a drone with onboard low-cost particle counter. Atmos. Environ. 2023, 314, 120085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Houdt, G.; Mosquera, C.; Nápoles, G. A review on the long short-term memory model. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2020, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudemeyer, R.C.; Morris, E.R. Understanding LSTM—A Tutorial into Long Short-Term Memory Recurrent Neural Networks. arXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus. Climate Data Store, Programme of the European Union. Available online: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/ (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- DECKEE. What is the Maximum Visibility at Sea? DECKEE Waterway Management Platform. Available online: https://deckee.com/blog/what-is-the-maximum-visibility-at-sea (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Gupta, S.S.; Panchapakesan, S. Some Statistical Techniques for Climatological Data; Purdue University: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Magnano, L.; Boland, J.W.; Hyndman, R.J. Generation of synthetic sequences of half-hourly temperature. Environmetrics 2008, 19, 818–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA. Historical Hurricane Tracks, NOAA Office for Coastal Management. Available online: https://coast.noaa.gov/hurricanes/#map=4/32/-80 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- NWS. Tropical Cyclone Definitions, National Weather Service (NWS). Available online: https://www.weather.gov/mob/tropical_definitions (accessed on 9 January 2026).

- Mahmood, H.N.; Ismail, W. Visibility parameter in sand/dust storms’ radio wave attenuation equations: An approach for reliable visibility estimation based on existing empirical equations to minimize potential biases in calculations. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H. The performance of three exponential decay models in estimating tropical cyclone intensity change after landfall over China. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 792005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venu, S.; Gurusamy, M. A comprehensive review of path planning algorithms for autonomous navigation. Results Eng. 2025, 28, 107750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchi, J.; Hazan, E.; Singer, Y. Adaptive subgradient methods for online learning and stochastic optimization. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2121–2159. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Cao, Z.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, J. A survey of optimization methods from a machine learning perspective. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2020, 50, 3668–3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Input Feature | Unit | Source | Short Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precipitation | Millimeter | Onboard sensor/drone | Gridded rainfall measurement |

| Cloud Cover | Percentage | Onboard sensor/drone | Fraction of the grid covered by clouds |

| Dry-Bulb Temperature | Fahrenheit | Onboard sensor/drone | Gridded temperature measurement |

| Dew-Point Temperature | Fahrenheit | Onboard sensor/drone | Temperature at which air becomes saturated with water vapor |

| Surface Pressure | Inch of Mercury | Onboard sensor/drone | Proportional to the mass of air over the location |

| Wind Speed | Mile/hour (mph) | Onboard sensor/drone | Wind speed at current or remote locations |

| Wind Direction | Degree | Onboard sensor/drone | Wind direction at current or remote locations |

| Observed Visibility | Mile | Onboard sensors/drone | Current visibility used for future visibility forecasting |

| Solar Elevation | Degree | Derived from latitude, longitude, and time | Approximation of the Sun’s elevation (−90° to 90°) |

| Solar Elevation Cos/Sin | Unitless | Derived from solar elevation | Sine and cosine of solar elevation for smooth diurnal modeling |

| Model Type | Sequence Length (τ) | Minibatch Size (b) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tested Values | Chosen Value | Tested Values | Chosen Value | |

| Diurnal Model | 12, 24, 36, 72, 96 | 72 | 12, 36, 72, 144, 288, 576 | 576 |

| Storm Model | 3, 6, 12, 24, 36 | 6 | 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 12 | 2 |

| Hyperparameter | Tested Values | Chosen Value |

|---|---|---|

| LSTM Neurons | 32, 64, 128, 256 | 256 |

| Dense Neurons | 32, 64, 128, 256 | 128 |

| Dropout Rate | 0%, 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, 50% | 30% |

| Optimizer | Adam, SGD, RMSProp | Adam |

| Activation Function | Leaky ReLu, Relu, Sigmoid | ReLu |

| Epochs (pre-training) | 50, 100, 150, 200 | 100 |

| Epochs (real-time training) | 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 | 10 |

| Learning Rate (pre-training) | 0.03, 0.01, 0.003, 0.001, 0.0003, 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| Learning Rate (real-time training) | 0.0001, 0.00005, 0.00003, 0.00001 | 0.00005 |

| Month | With Real-Time Training | Without Real-Time Training | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly Accuracy | Monthly MAE | Monthly Accuracy | Monthly MAE | |

| March | 94.91% | 0.31 miles | 84.97% | 1.07 miles |

| April | 95.02% | 0.22 miles | 78.87% | 1.37 miles |

| May | 96.45% | 0.21 miles | 79.39% | 1.52 miles |

| Noise Level | STD | MAPE | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Noise | 0.0 | 6.70% | 93.30% |

| Very Small Noise | 0.05 | 6.83% | 93.16% |

| Small Noise (chosen value) | 0.2 | 7.82% | 92.18% |

| Moderate Noise | 0.5 | 8.62% | 91.38% |

| High Noise | 1.0 | 17.25% | 82.75% |

| Very High Noise | 2.0 | 32.61% | 67.39% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Girard, W.; Xu, H.; Yan, D. SeADL: Self-Adaptive Deep Learning for Real-Time Marine Visibility Forecasting Using Multi-Source Sensor Data. Sensors 2026, 26, 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020676

Girard W, Xu H, Yan D. SeADL: Self-Adaptive Deep Learning for Real-Time Marine Visibility Forecasting Using Multi-Source Sensor Data. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):676. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020676

Chicago/Turabian StyleGirard, William, Haiping Xu, and Donghui Yan. 2026. "SeADL: Self-Adaptive Deep Learning for Real-Time Marine Visibility Forecasting Using Multi-Source Sensor Data" Sensors 26, no. 2: 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020676

APA StyleGirard, W., Xu, H., & Yan, D. (2026). SeADL: Self-Adaptive Deep Learning for Real-Time Marine Visibility Forecasting Using Multi-Source Sensor Data. Sensors, 26(2), 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020676