1. Introduction

Accurate and timely information on crop distribution is essential for agricultural production management, yield estimation, and sustainable land use planning [

1,

2]. Crop classification is essential for agricultural monitoring, providing the foundation for tracking crop growth, optimizing planting structures, and ensuring food security, while also supporting agricultural research, resource management, breeding innovation, and sustainable development [

3,

4]. The development of advanced crop distribution mapping algorithms is critical for establishing a robust and generalizable model applicable to large-scale agricultural monitoring via remote sensing [

5,

6]. Given the increasing pressures of population growth, global environmental change, and limited arable land resources, obtaining reliable and efficient crop classification has emerged as an urgent applied research challenge [

7,

8]. Crop growth dynamics are governed by critical factors including soil conditions, irrigation systems, and climatic variables [

9]. Precise crop classification—essential for growth optimization due to species-specific environmental adaptability—forms the foundation for effective yield estimation and prediction [

10,

11,

12].

Traditional crop classification approaches often rely exclusively on intensive ground surveys to characterize farmland attributes, posing significant economic and temporal constraints. As a non-contact information acquisition tool, remote sensing is extensively applied in agriculture and land management [

10]. Remote sensing data with spatiotemporal heterogeneity substantially enhance the classification accuracy of land cover types, thereby enabling more precise mapping and analysis of farmland distribution [

13]. Compared to conventional methods, remote sensing offers distinct advantages: (1) simultaneous large-scale observation with enhanced analytical timeliness; (2) reduced susceptibility to weather and environmental interference, lowering operational costs while improving reliability; and (3) establishment of comprehensive farmland production databases.

Optical remote sensing for crop classification has matured over decades. For land cover and land use classification, multi-temporal high-resolution optical imagery has become a critical tool—this shift has been enabled by the expanding repository of remote sensing satellite data. The calculation of the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) serves as a reliable method for extracting critical information on surface vegetation [

14,

15], and this index is widely used to predict key growth stages, such as the grain-filling and ripening stages of rice, providing robust technical support for the development of crop growth models. Rice spectral response varies across phenological stages. During early emergence and tillering, sparse canopy and low biomass result in low red and NIR reflectance, yielding lower NDVI and EVI values. As the canopy thickens and chlorophyll increases during tillering and jointing, NIR reflectance and VIs peak [

16,

17]. In the heading and flowering stages, with full canopy closure and maximum LAI, NIR reflectance and VIs reach their highest values, strongly correlating with yield [

18,

19,

20]. In the grain filling stage, chlorophyll decreases and the canopy yellows, causing a drop in NIR and an increase in red reflectance, leading to a decline in NDVI and EVI. At maturity, as grains ripen and leaves yellow, red and SWIR reflectance increase, while NIR decreases, with a distinct red-edge shift [

21]. These spectral changes are critical for differentiating rice growth stages and are widely used in optical remote sensing phenology studies. Moreover, the integration of NDVI and the Normalized Water Index (NDWI) has demonstrated promising results in crop recognition, particularly for rice [

22]. While optical remote sensing technology exhibits strengths such as fine resolution and well-defined feature attributes, its effectiveness is often limited by weather conditions. For instance, crops are predominantly cultivated in subtropical regions, where the planting season often overlaps with the rainy season, posing significant challenges for monitoring. The persistent influence of environmental factors may render the accumulation of temporal imagery insufficient to significantly enhance crop classification accuracy.

Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) penetrates clouds, fog, and snow, enabling direct observation of surface targets [

23]. This all-weather capability drives its increasing adoption in crop classification studies [

24,

25,

26,

27]. In addition, beyond these conventional applications, advanced polarimetric decomposition techniques have significantly enhanced SAR’s sensitivity to vegetation structure [

28,

29]. Researchers have discovered that polarimetric SAR features exhibit higher sensitivity to crop structure and biophysical characteristics than optical vegetation index features [

19]. The full polarimetric SAR signals show a strong potential in the application of effective differentiation of various crops types [

30]. In agriculture, model-based polarimetric decomposition based on physical scattering models quantifies parameters like volume scattering power and surface scattering power, providing a mechanistic basis for crop classification. Here, volume scattering is correlated with crop biomass and height characterizes canopy multiple scattering [

31], while surface scattering reflects soil interface scattering [

32]. Studies on scattering mechanisms based on the two-dimensional H-α eigenspace have shown that significant progress has been made in the differentiation of target types using the eigenvalues of the coherence matrix and its associated eigenvectors [

33,

34,

35]. The

/

/

/ decomposition parameters constitute a robust analytical framework for polarimetric SAR image interpretation and has been extensively applied across diverse areas, including crop classification, land use classification [

34,

36]. These parameters outperform traditional backscatter coefficients by isolating scattering mechanisms, thereby improving classification accuracy. Current Sentinel-1-based crop classification methodologies predominantly rely on backscatter coefficients and

/

/

/ decomposition features [

37,

38,

39,

40], underutilizing advanced polarimetric information derived from model-based decomposition approaches.

The contribution of single SAR images to rice mapping needs to be improved [

41], and future research needs to deepen the coupling of scattering mechanisms and agronomic parameters to promote the paradigm shift in crop classification from two-dimensional mapping to three-dimensional synergistic perception of structure and physiological state. Long-time-series SAR data can effectively monitor the scattering characteristic changes during crop growth [

42,

43], so it is advantageous to utilize long-time-series images for crop classification. Current Sentinel-1-based crop classification methodologies predominantly rely on backscatter coefficients and

/

/

/ decomposition features [

37,

38,

39,

40], underutilizing advanced polarimetric information derived from model-based decomposition approaches. Therefore, fully utilizing multi-temporal polarization decomposition features can effectively characterize crop structural changes and further enhance classification performance [

44,

45].

The main objectives of this case study are summarized as follows: (1) To assess the accuracy, temporal regularity, and classification effectiveness of multi-temporal Sentinel-2 imagery for agricultural crop classification with different crops. (2) To evaluate the classification performance, temporal regularity, and crop-recognition capabilities of multi-temporal Sentinel-1 data, emphasizing the contribution of model-based polarimetric decomposition features. (3) From a practical perspective, to determine the most suitable crop classification strategy for the research region by comparatively analyzing the Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 images.

3. Results

3.1. Multi-Temporal Sentinel-2 Images Classification Results

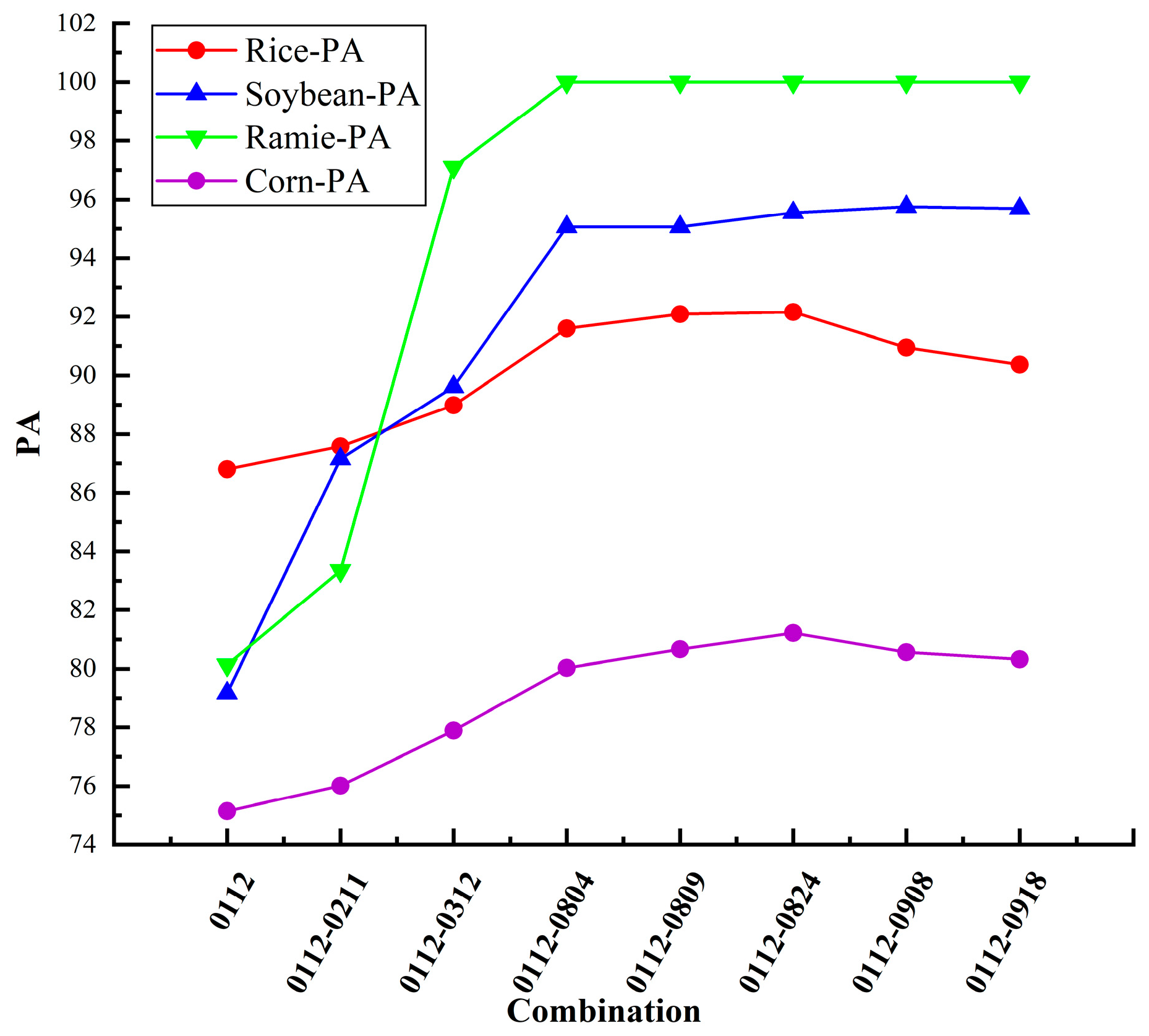

To evaluate the temporal properties of Sentinel-2 optical imagery for crop classification within the study area, a series of experiments were designed and implemented. Using the multi-temporal Sentinel-2 dataset employed in this study—comprising 8 acquisitions from different phenological stages—we progressively combined images across time and quantitatively analyzed the resulting classification accuracy for each crop type. This accuracy was measured as a function of the number of images used, as illustrated in

Figure 5. The PA for each crop is shown in

Table 4. The results indicate that integrating four optical images markedly enhances the classification performance for all four crop types. Maximum accuracy is achieved with the inclusion of six images, beyond which further additions lead to a decline in performance.

To further investigate the contribution of early-season imagery (January and February), we conducted a comparative experiment by excluding these months from the input dataset. The results indicated a decrease in Overall Accuracy to 91.56% (

Table 5). This finding confirms that despite the absence of standing crops, the spectral information from the fallow period—serving as a phenological baseline and aiding in the separation of cropland from evergreen vegetation—is essential for achieving optimal classification performance.

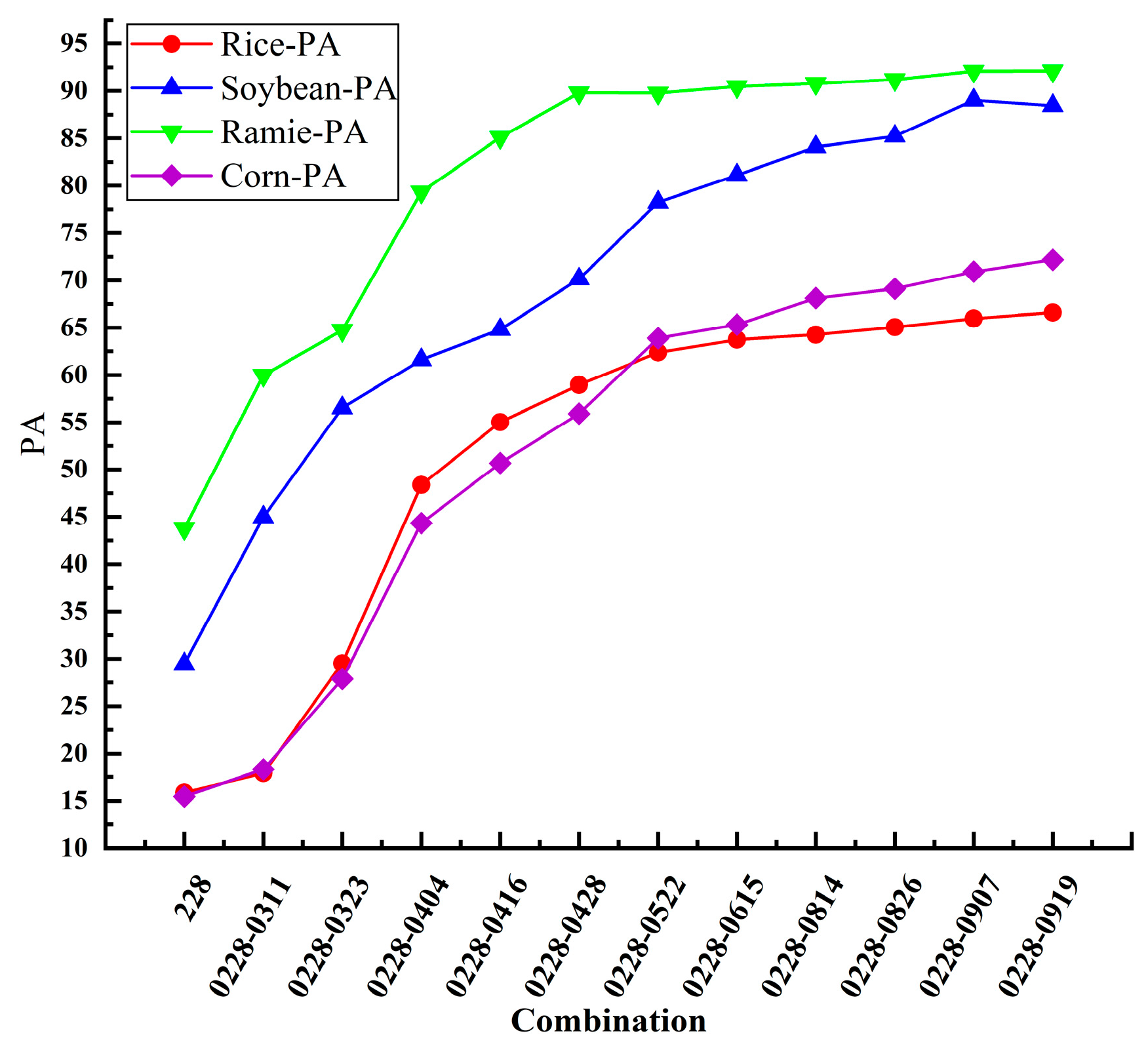

3.2. Multi-Temporal Sentinel-1 Intensity Images Classification Results

To evaluate the contribution of Sentinel-1 dual-polarization decomposition features to crop classification, a controlled experiment was designed utilizing only preprocessed Sentinel-1 backscatter intensity images. The relevant results are shown in

Figure 6, with the accuracy for each crop listed in

Table 6. The subsequent classification results demonstrated that ramie and soybeans achieved recognition accuracies of 92.18% and 89.03%, respectively, when using a time series of 12 Sentinel-1 intensity images. However, the accuracy of rice, the main crop in the planting area, was only 66.59%. Therefore, classification based solely on Sentinel-1 intensity images cannot meet application requirements. It is necessary to extract more features based on polarimetric SAR data to enhance the classification effect.

When only the 12 preprocessed intensity images from Sentinel-1 were used, the classification outcome proved inadequate. The OA of the classification results is 65.00%, the Kappa coefficient is 0.52. The PA values of the four crops including rice, soybean, corn, and ramie are 66.59%, 89.03%, 72.18%, 92.18%, respectively. Only utilizing the backscattering products of Sentinel-1 does not achieve good classification results. Consequently, in subsequent experiments, we leveraged dual-polarization decomposition to enhance the feature space of Sentinel-1 imagery and more comprehensively evaluated its efficacy in crop classification.

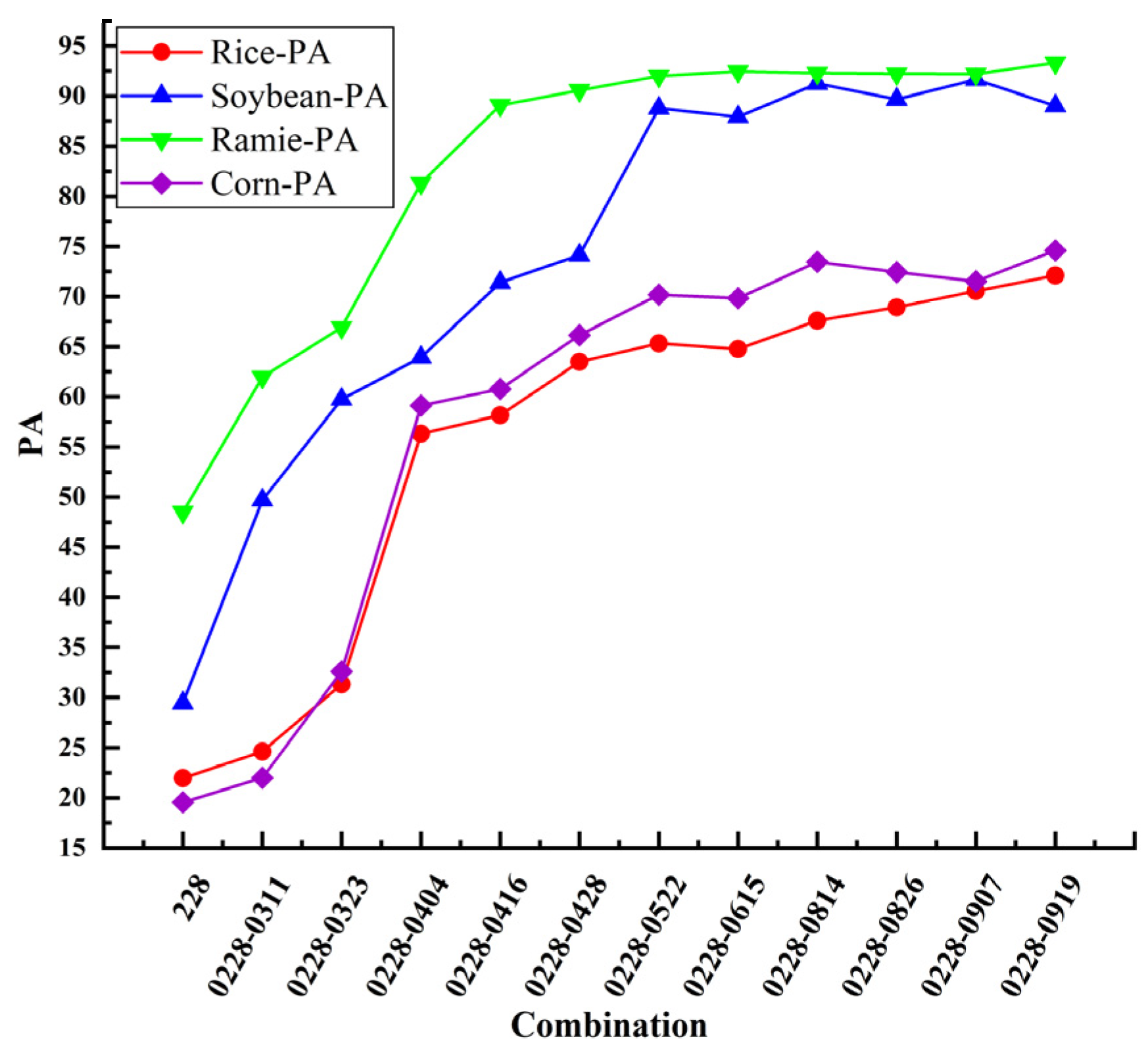

3.3. Multi-Temporal Sentinel-1 Features Images Classification Results

To improve the precision of crop type identification with Sentinel-1 imagery, based on the

matrix, we extracted the polarization decomposition features of Sentinel-1. And the temporal features of crop classification of Sentinel-1 data were obtained by using 12 Sentinel-1 images for crop classification. The classification accuracy for each crop is shown in

Table 7. We incrementally aggregated multi-temporal images and quantitatively assessed the per-crop classification accuracy, evaluated as functions of image count variations, as shown in

Figure 7. The overall classification accuracy variation for multi-temporal optical data and multi-temporal SAR data is shown in

Figure 8.

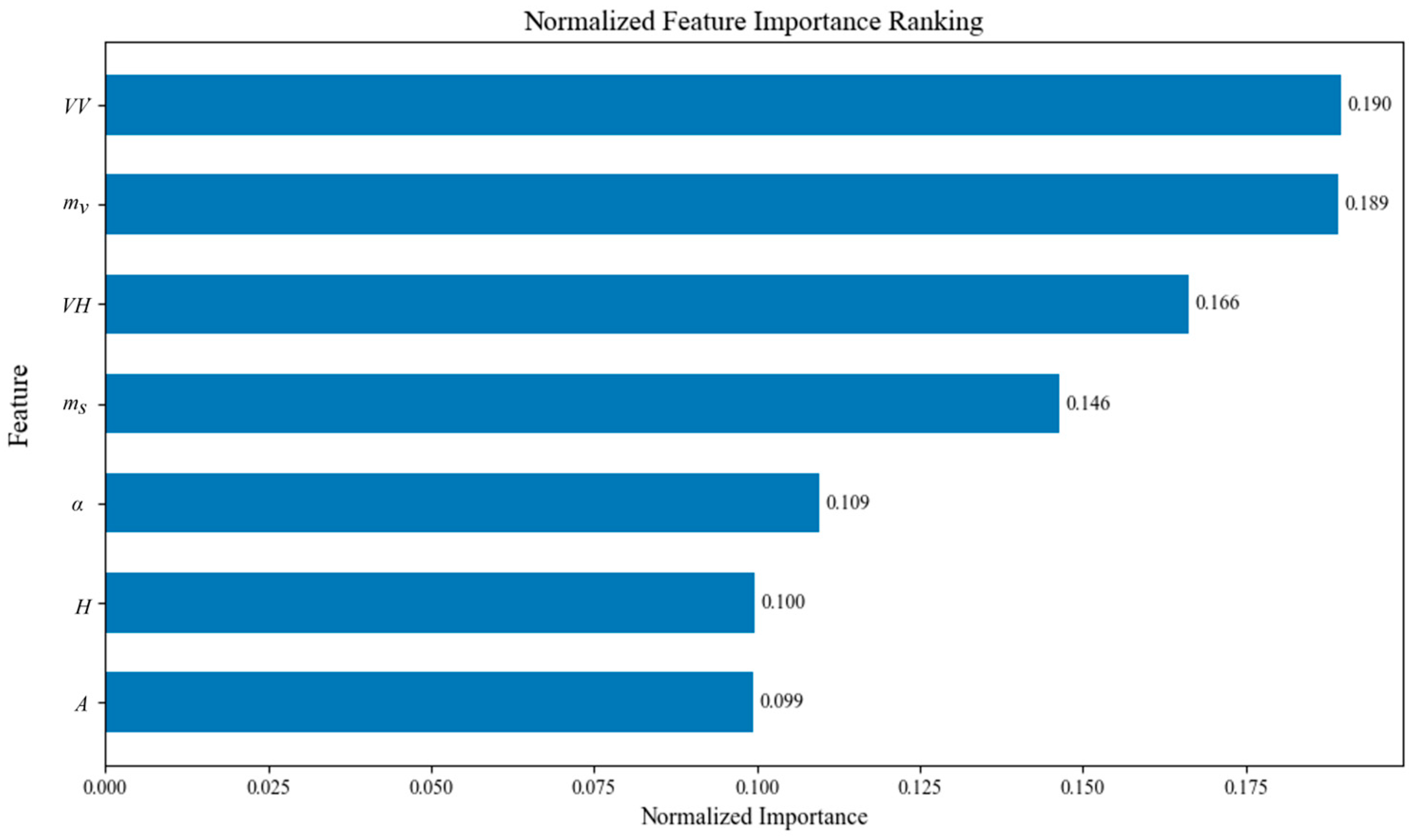

Based on experimental results, it demonstrated that after adding the polarization decomposition feature, the classification accuracies of the four crops are improved to different degrees compared with the classification results of Sentinel-1 intensity images. Among them, the classification accuracy of rice is improved by 5.50%, soybean by 2.60%, corn by 2.41%, and ramie by1.35%. Notably, rice displayed the most pronounced enhancement, which is particularly valuable for operational monitoring since it is the most extensively cultivated crop in the region.

3.4. The Best Crop Classification Strategy

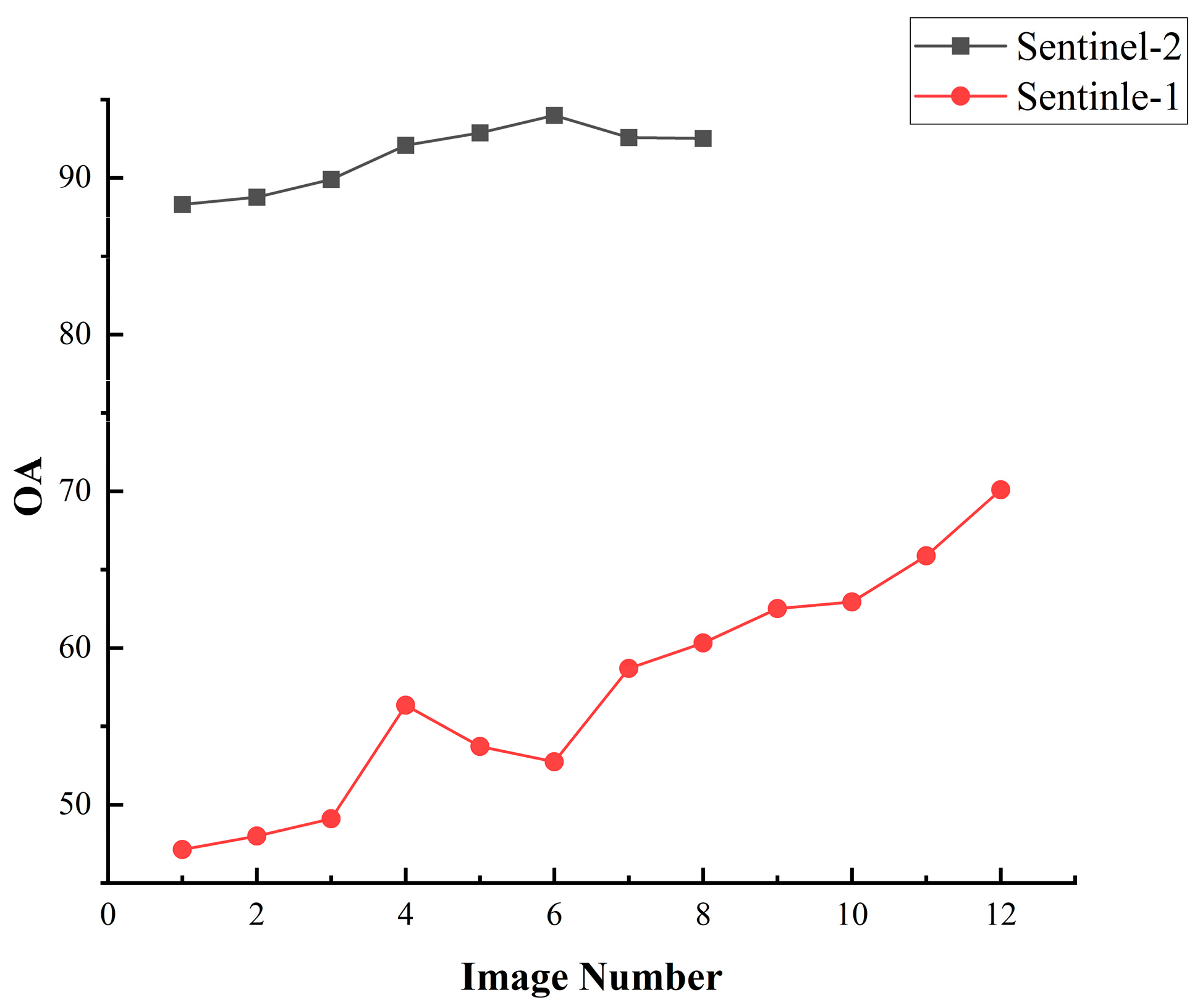

With the time-series classification curves from both satellite systems now established, we proceeded to conduct comparative experiments aimed at developing an optimal crop classification strategy for the region.

Section 3.1 and

Section 3.3 have illustrated the OA of classifications derived from Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 imagery. The results demonstrate that the classification accuracy of optical images initially rises with the inclusion of more temporal data, peaks at an optimal number of images, and subsequently declines with further additions. The overall classification accuracy of optical images peaks at 6 images. However, the overall accuracy of SAR data increases with the number of images and reaches a peak at 12 images. Several studies have demonstrated that combining Sentinel-1/2 time series could significantly improves crop discrimination accuracy [

61,

62,

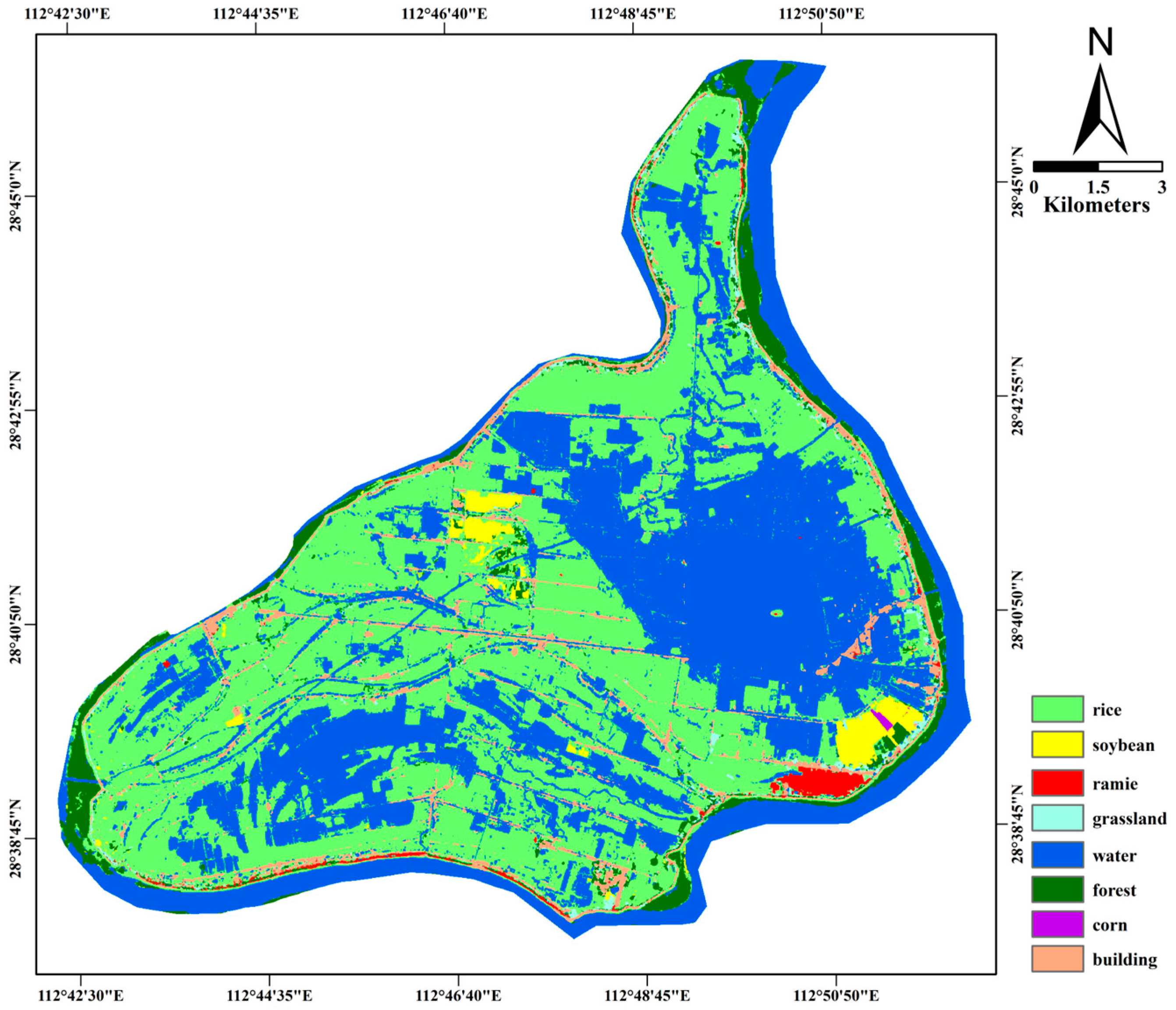

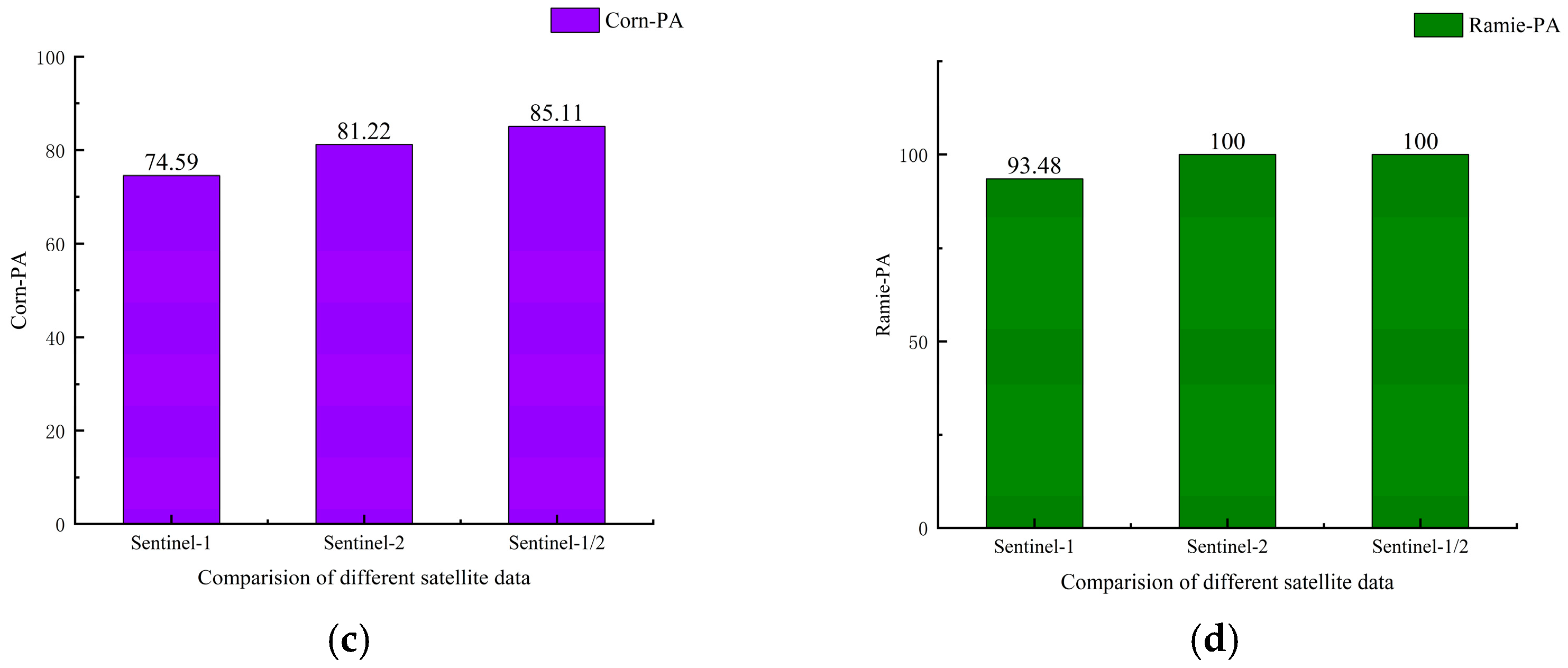

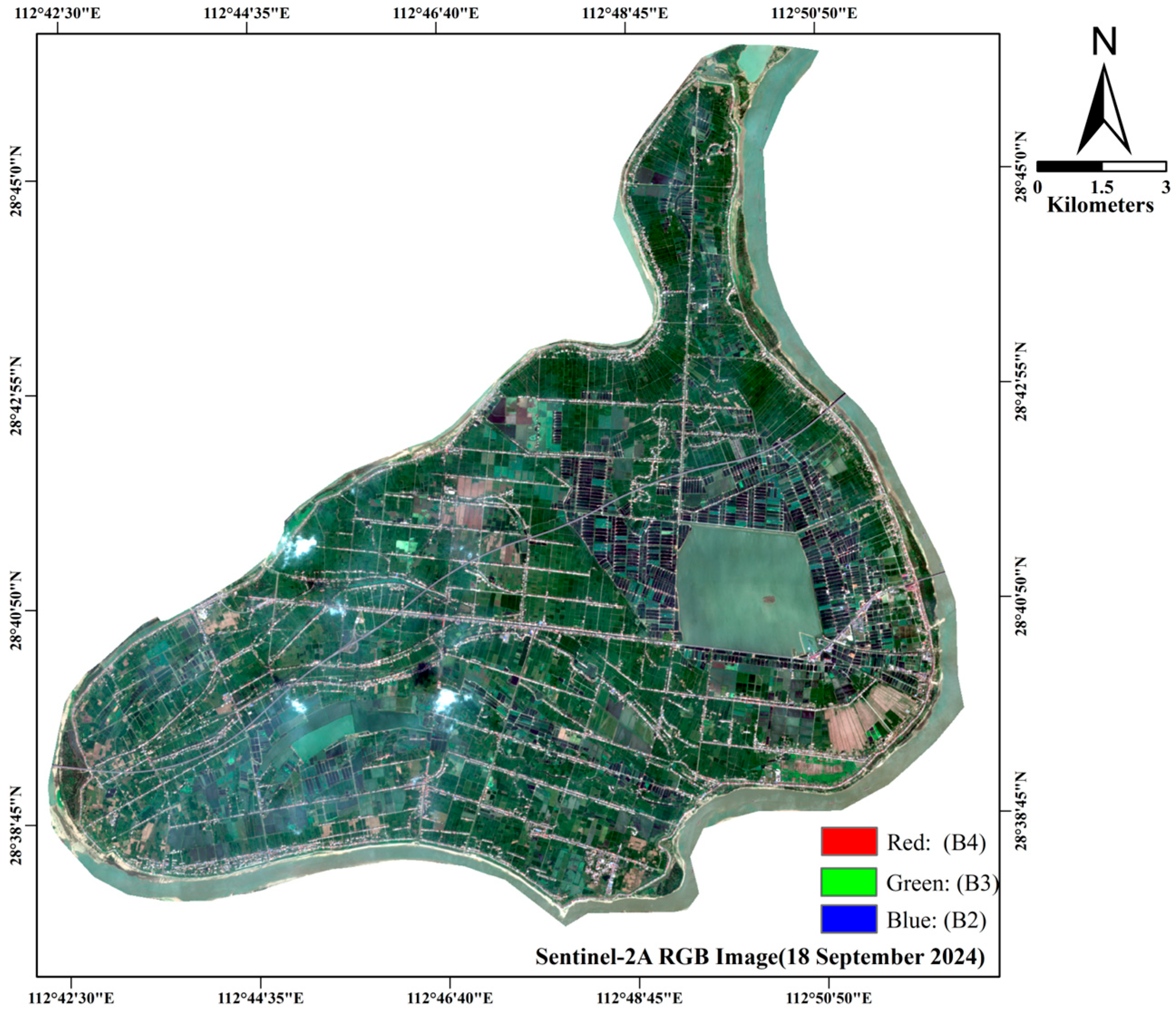

63]. Therefore, all Sentinel-1 feature images and the combination of Sentinel-2 images from 12 January 2024 to 24 August 2024 were selected for crop classification as the most applicable classification scheme for the experimental area. A thematic map illustrating the output of the best classification strategy is provided in

Figure 9 and Confusion Matrix as shown in

Table 8. The performance of each crop under the optimal classification strategy is shown in

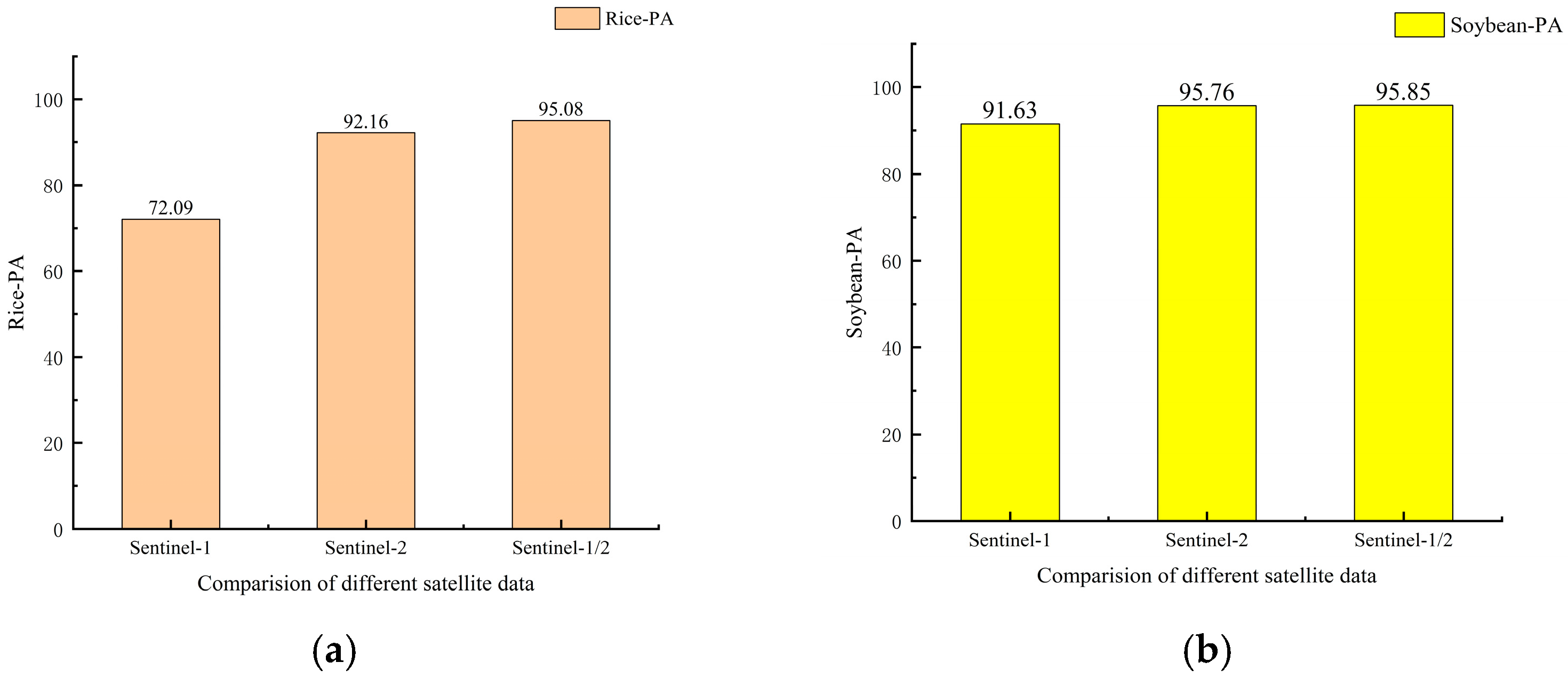

Figure 10.

A comparison of the accuracy matrices reveals that the overall classification accuracy with polarimetric decomposition features reaches 94.20%, representing only a 0.20% improvement over the best result achieved using optical data alone. Although this increase is modest, focusing on specific crop types reveals more significant improvements. Notably, the classification accuracy for rice improved by 2.92%, and for corn, it increased by 3.89%. This enhancement, while not substantial in terms of overall accuracy, is particularly significant in practical applications, especially under challenging conditions where optical imagery is either absent or of poor quality. The study area’s climatic conditions, characterized by persistent precipitation and prolonged cloud cover during the rice and corn growing seasons, as well as intercropping practices, make it difficult to achieve reliable classification when relying solely on optical imagery. The integration of SAR data, particularly the polarimetric decomposition features, effectively addresses these challenges and improves the classification accuracy of specific crops in the study area, demonstrating its crucial application value when optical data quality is compromised or missing.