Design and Error Calibration of a Machine Vision-Based Laser 2D Tracking System

Abstract

1. Introduction

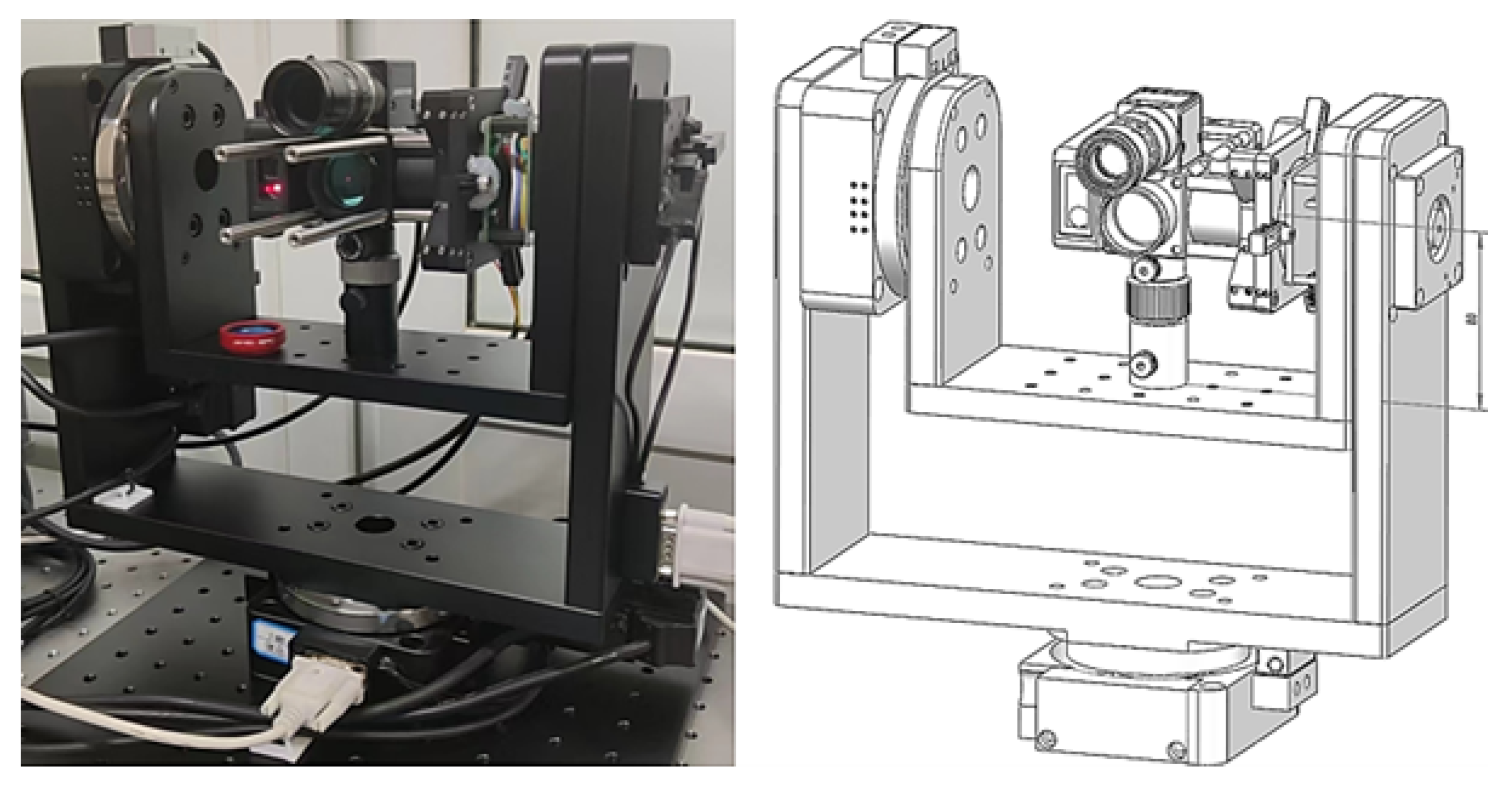

2. Overall System Design

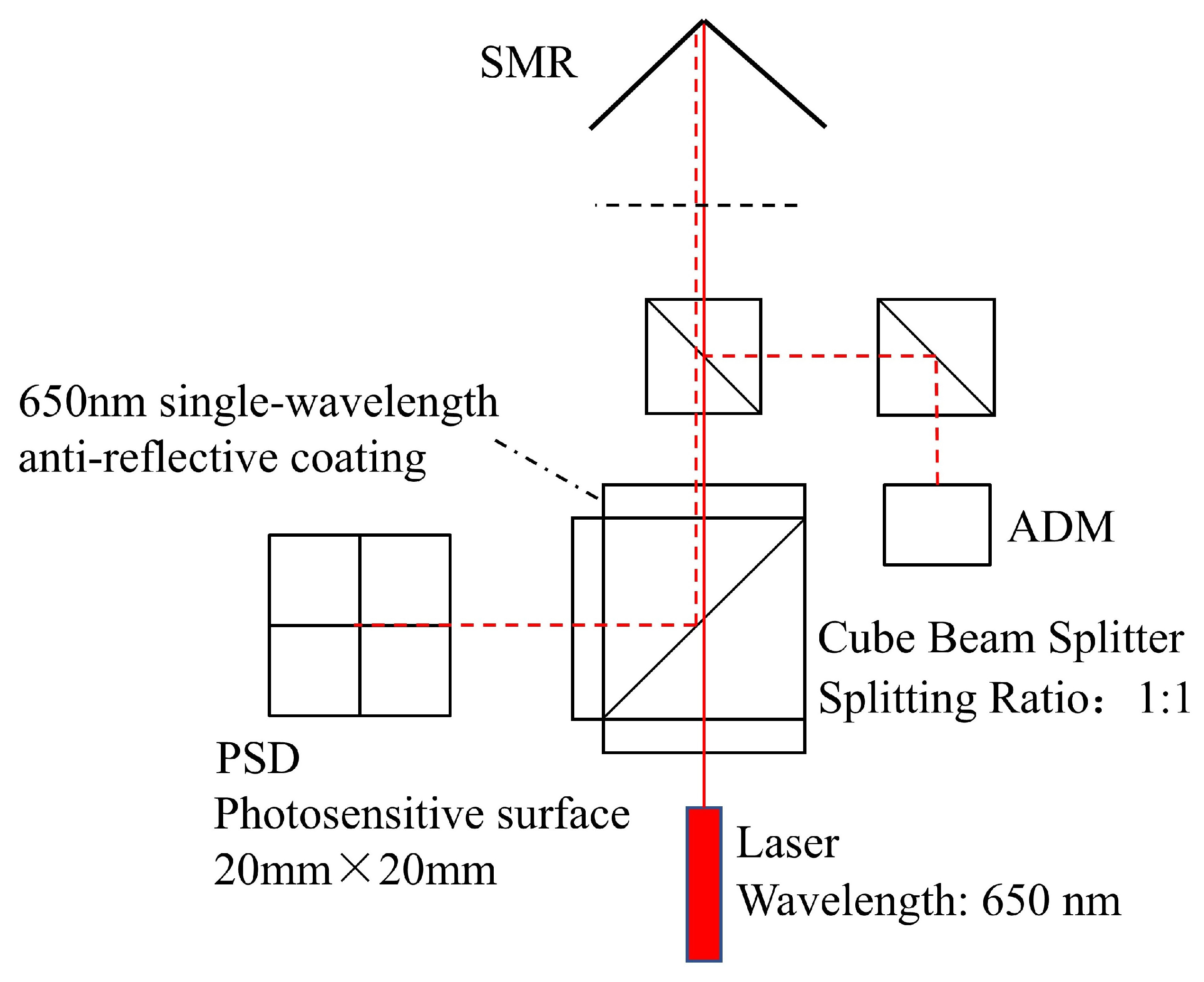

- The laser and the ADM distance measurement module each maintain their own independent coaxial optical paths. These two paths achieve off-axis coordination through a cube beam splitter, eliminating the requirement for full-link optical path coaxiality and thereby significantly reducing the system’s dependence on high-precision mechanical assembly.

- The optical path of the visual camera is completely independent from the main optical axis, with no need for rigid mechanical calibration or binding between them. Instead, laser beam guidance is accomplished solely by algorithmically matching the position of the SMR in the camera image with the pointing direction of the main optical axis.

3. Error Calibration Method

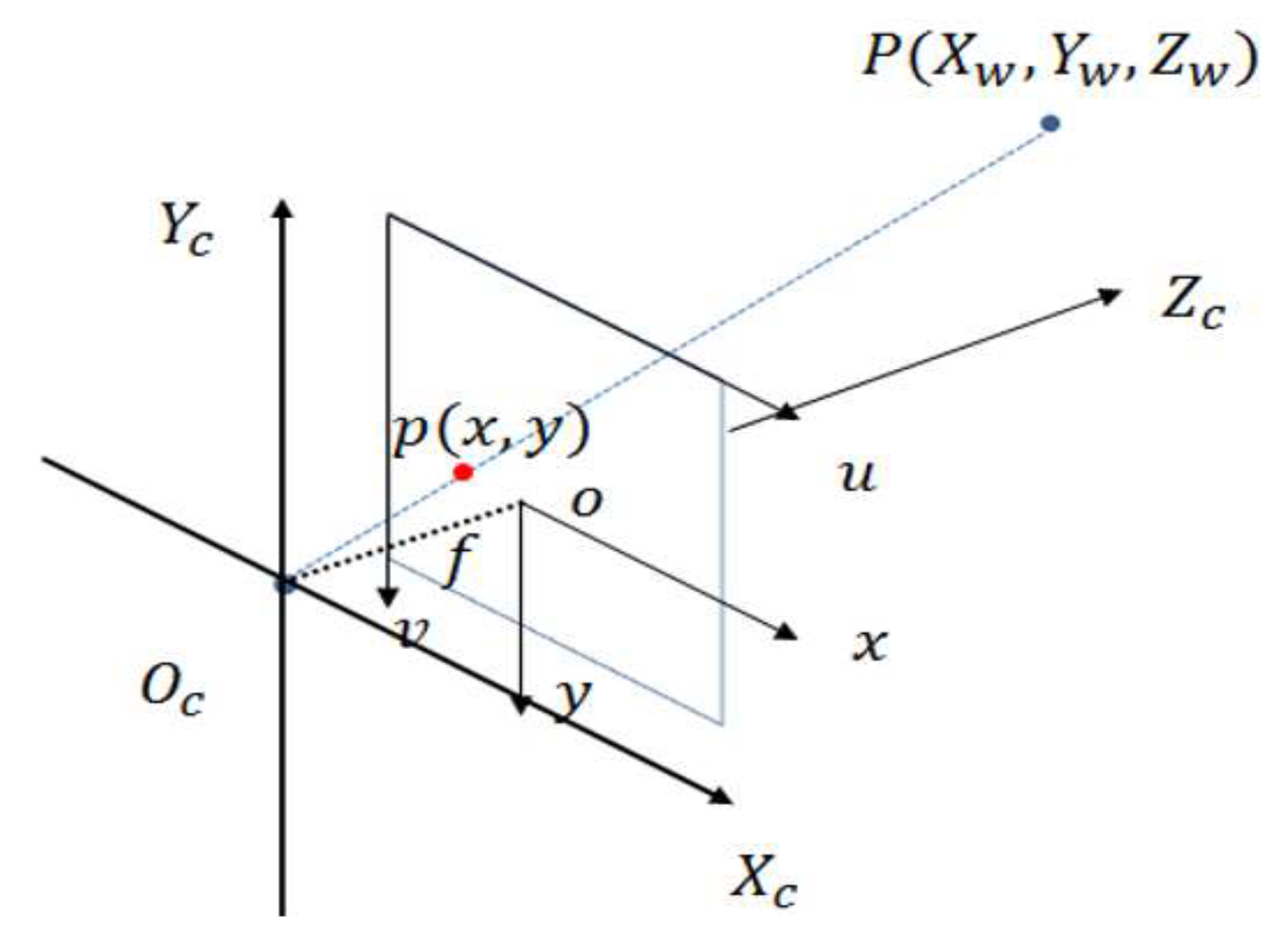

3.1. Monocular Camera Calibration

3.2. Optical Axis Calibration of the Tracking Head

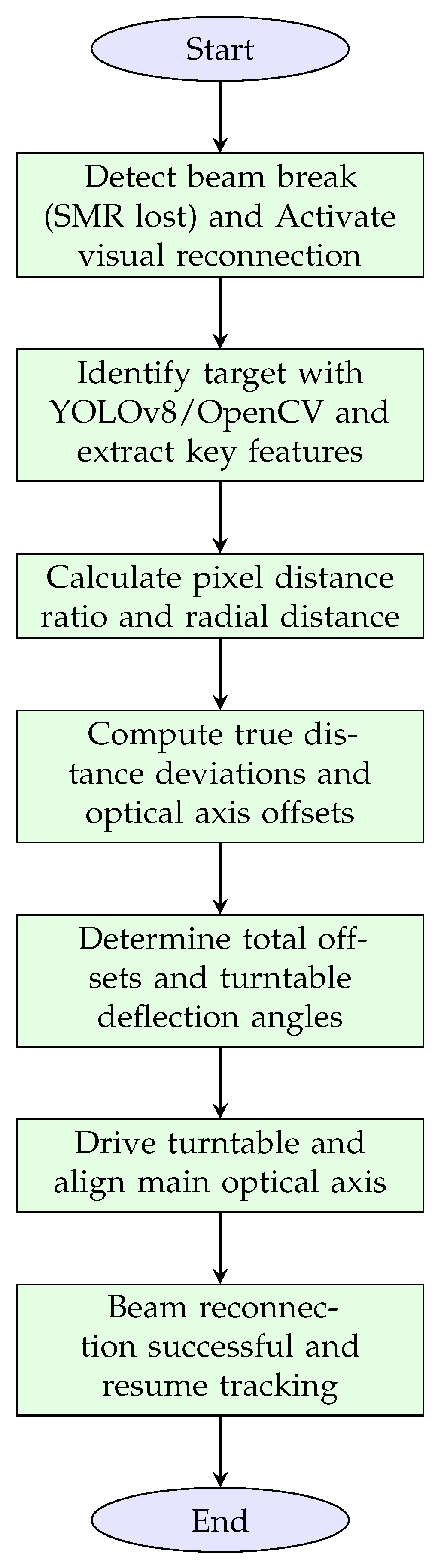

3.3. Principle of Light Interruption and Reconnection Based on Visual Indexing

4. System Implementation and Experiments

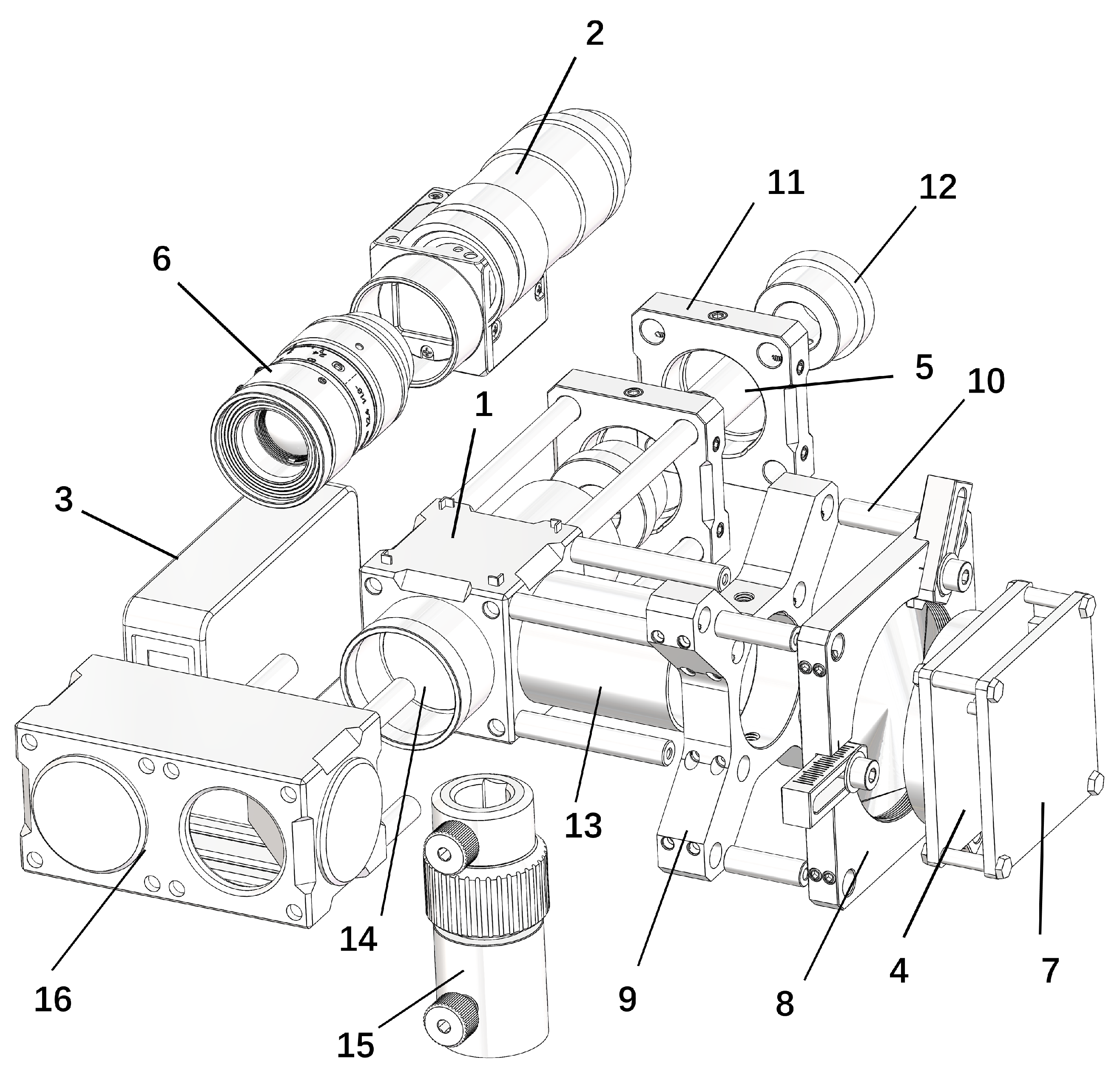

4.1. Hardware Selection and Assembly

4.2. Software Design

4.3. The Workflow of the Laser Tracking System

4.4. Precision Testing Experiment

- Quantitative improvement potential of angular error. The current angular error (caused by encoder resolution, turntable axis orthogonality deviation, and mechanical installation errors) results in a spatial deviation of approximately 0.052 mm at a measurement distance of 1 m, accounting for 27.5% of the total error (0.052/0.189). By adopting a higher-resolution encoder (improving the repeatability from the existing 0.003° to 0.001°) and correcting the axis deviation through an orthogonality error compensation algorithm, the spatial deviation caused by angular error can be reduced to 0.017 mm. This single reduction contributes approximately 0.035 mm, corresponding to an 18.5% decrease in the total measurement error.

- Quantitative improvement potential of distance measurement error. The inherent error of the distance measurement module (random noise + systematic deviation) is approximately 0.06 mm, accounting for 31.7% of the total error (0.06/0.189). By introducing a temperature compensation algorithm (correcting the impact of ambient temperature on distance measurement accuracy) and moving average filtering to handle random noise, the distance measurement error can be reduced to 0.03 mm. This single reduction contributes approximately 0.03 mm, corresponding to a 15.9% decrease in the total measurement error.

- Quantitative improvement potential of assembly error. The current contribution of assembly error (including axis orthogonality deviation, optical component installation errors, and central axis misalignment) is approximately 0.077 mm, accounting for 40.8% of the total error (0.077/0.189). By improving mechanical processing precision (optimizing the axis orthogonality deviation from the current 0.01 mm to 0.005 mm) and performing precise calibration of the optical axis using a laser interferometer, the assembly error can be reduced to 0.01 mm. This single reduction contributes approximately 0.067 mm, corresponding to a 35.4% decrease in the total measurement error.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SMR | Spherically Mounted Retroreflector |

| PSD | Position Sensitive Detector |

| ADM | Absolute Distance Meter |

| SVD | Singular Value Decomposition |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| ME | Mean Error |

References

- Lv, Z.; Cai, L.; Wu, Z.; Cheng, K.; Chen, B.; Tang, K. Target Locating of Robots Based on the Fusion of Binocular Vision and Laser Scanning. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Computer Engineering and Artificial Intelligence (ICCEAI), Shanghai, China, 27–29 August 2021; pp. 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Yang, T.; Wang, X.; Ma, Z.; Li, X.; Jiang, H.; Zhao, H. On-line Measurement System of Aerospace Large Components Based on Vision Measurement System and Robotic Arm. In Proceedings of the 2024 9th Asia-Pacific Conference on Intelligent Robot Systems (ACIRS), Dalian, China, 18–20 July 2024; pp. 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Cui, C.; Li, J.; Zhou, W.; Dong, D.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, G.; Qiu, Q.; Wang, S. High-velocity measurement method in dual-frequency laser interference tracker based on beam expander and acousto-optic modulator. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 24230–24242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, X.; Liu, F.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Cheng, P. Omnidirectional Vector Measurement Method for Accurate Laser Positioning System. In Proceedings of the 2024 7th International Conference on Intelligent Robotics and Control Engineering (IRCE), Xi’an, China, 7–9 August 2024; pp. 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Pan, Y.; Lin, J.; Liu, Y.; Shang, Y.; Yang, S.; Cao, H. Automatic Guidance Method for Laser Tracker Based on Rotary-Laser Scanning Angle Measurement. Sensors 2020, 20, 4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutilba, U.; Gomez-Acedo, E.; Kortaberria, G.; Olarra, A.; Yagüe-Fabra, J.A. Traceability of On-Machine Tool Measurement: A Review. Sensors 2017, 17, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, D.; Li, J.; Feng, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Cui, J.; Wu, L. Method and system for simultaneously measuring six degrees of freedom motion errors of a rotary axis based on a semiconductor laser. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 24127–24141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASME B89.4.19-2021; Performance Evaluation of Laser-Based Spherical Coordinate Measurement Systems. American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2021.

- ISO 10360-10:2021; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Acceptance and Reverification Tests for Coordinate Measuring Systems (CMS)—Part 10: Laser Trackers. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Dong, M.; Qin, X.; Fu, Y.; Xu, H.; Wang, J.; Wu, D.; Wang, Z. A Vision Algorithm for Robot Seam Tracking Based on Laser Ranging. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Computer, Control and Robotics (ICCCR), Shanghai, China, 24–26 March 2023; pp. 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Chen, T.; Sun, L.; Fan, P. High Precision Camera Calibration Method Based on Full Camera Model. In Proceedings of the 2024 36th Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), Xi’an, China, 25–27 May 2024; pp. 4218–4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. A Flexible New Technique for Camera Calibration. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2000, 22, 1330–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-López, L.E.; Luviano-Cruz, D.; Cota-Ruiz, J.; Díaz-Roman, J.; Sifuentes, E.; Silva-Aceves, J.M.; Enríquez-Aguilera, F.J. A Configurable Parallel Architecture for Singular Value Decomposition of Correlation Matrices. Electronics 2025, 14, 3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.C.; Hua, H.Q.B.; Pham, P.T. Development of a vision system integrated with industrial robots for online weld seam tracking. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 119, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W. Research and Design of Weld Seam Tracking Algorithm Based on Machine Vision and Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 5th International Conference on Power, Intelligent Computing and Systems (ICPICS), Shenyang, China, 14–16 July 2023; pp. 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.; Shi, S.; Yang, L.; Lin, J.; Zhu, J. Dynamic measurement method based on temporal-spatial geometry constraint and optimized motion estimation. Measurement 2024, 227, 114269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic Indicators | Proposed System | API T3 | Leica AT960 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total System Weight | ≤10 kg (simplified structure) | (with controller) | (integrated host) |

| Core Optical Architecture | Dual-mirror coaxial design (adapted for short-distance) | Built-in multi-optical components (general long-distance) | Built-in multi-optical components (general long-distance) |

| Anti-interference Adaptation Scenarios | Short-distance, indoor complex light environment (no external shading required) | Long-distance, stable lab environment (temperature control dependent) | Long-distance, standard working conditions (temperature control dependent) |

| Measurement Distance Range | (short-distance dedicated) | (long-distance general) | (long-distance general) |

| Total Calibration Time (including preheating) | ≤5 min (rapid assembly) | (13 min preheating + 2 min calibration) | ≥12 min (professional operation required) |

| Main Application Scenarios | Short-distance high-precision assembly, indoor small-space measurement | Large-size workpiece inspection, long-distance positioning | Large equipment calibration, ultra-long-distance measurement |

| Figure Label | Component Category | Component Model | Origin (City, Country) | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cube Beam Splitter | M2-BS1 | Guangzhou, China | 1 |

| 2 | Industrial Camera | MV-CE060-10UC | Hangzhou, China | 1 |

| 3 | Rangefinder | L2 | Shenzhen, China | 1 |

| 4 | PSD Sensor | DRX-PSD500 | Shenzhen, China | 1 |

| 5 | Laser | HW650DMGX100-1660BD | Xi’an, China | 1 |

| 6 | Industrial Lens | MVL-HF1624M-10MP | Hangzhou, China | 1 |

| 7 | PSD Amplifier Circuit Board | DRX-2DPSD-OA11 | Shenzhen, China | 1 |

| 8 | Adjustable Fixing Frame | CRD-2X | Guangzhou, China | 1 |

| 9 | Cage Plate Adapter | LPCM-C | Guangzhou, China | 1 |

| 10 | Cage Coaxial Rod | PCM-S19 | Guangzhou, China | 4 |

| 10 | Cage Coaxial Rod | PCM-S38 | Guangzhou, China | 4 |

| 10 | Cage Coaxial Rod | PCM-S76 | Guangzhou, China | 4 |

| 11 | Pressure Ring Lens Holder | CSJ-25 | Guangzhou, China | 2 |

| 12 | Laser Mounting Hole Frame | POL-12 | Guangzhou, China | 2 |

| 13 | Lens Light Shield Tube | CSA-45 | Guangzhou, China | 2 |

| 13 | Lens Light Shield Tube | CSA-08 | Guangzhou, China | 1 |

| 13 | Lens Light Shield Tube | CSA-08T | Guangzhou, China | 1 |

| 14 | Narrow Band Filter | NP650 | Guangzhou, China | 3 |

| 15 | Telescopic Optical Support Rod | CAT57-S | Guangzhou, China | 1 |

| 16 | Coaxial Light Shield Tube | Customized | Guangzhou, China | 1 |

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Image Size | 2048, 3072 |

| Radial Distortion | 0.0036, 0.4924 |

| Tangential Distortion | −0.0013, 0.0040141 |

| Structural Parameters | |

|---|---|

| Angle Range | Azimuth , Elevation |

| Platform Size | 165 × 80 mm |

| Transmission Ratio | 180:1 |

| Drive Mechanism | Worm gear and worm shaft mechanism |

| Motor | 100 W servo motor |

| Central Load Capacity | 10 kg |

| Accuracy Parameters | |

| Resolution | = (with 20 subdivisions) |

| Closed-Loop Mechanism | Grating closed-loop (resolution: ) |

| Maximum Speed | /s |

| Repeatability | |

| End Jump Accuracy | 10 m |

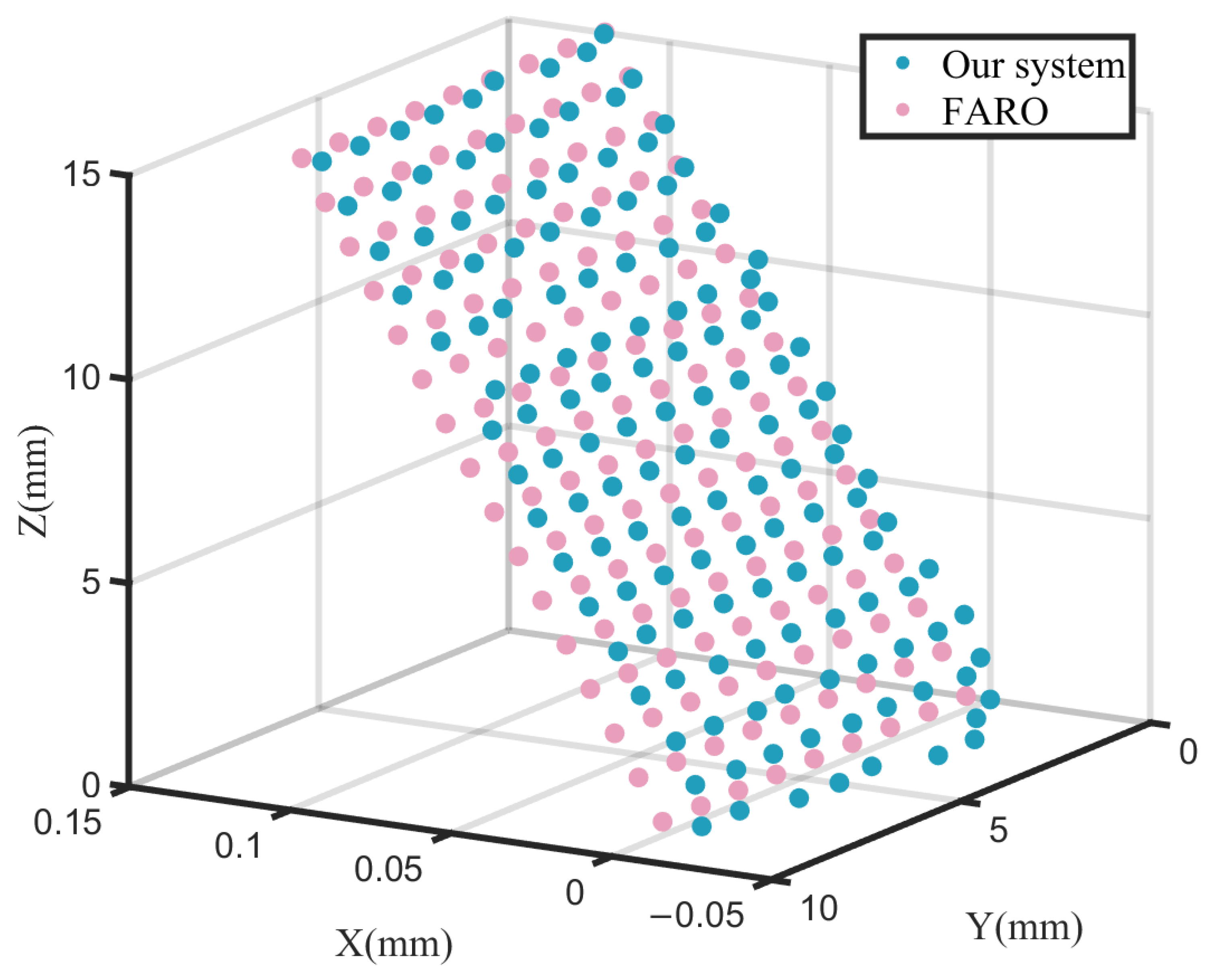

| Measurement Dimension | Mean Error (ME) | Maximum Error (R) | Standard Deviation (SD) | Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X Direction | −0.025 | 0.083 | 0.030 | 0.030 |

| Y Direction | 0.044 | 0.937 | 0.147 | 0.150 |

| Z Direction | 0.034 | 0.761 | 0.126 | 0.129 |

| Spatial Distance | 0.191 | 0.945 | 0.099 | 0.189 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lao, D.; Wang, X.; Chen, T. Design and Error Calibration of a Machine Vision-Based Laser 2D Tracking System. Sensors 2026, 26, 570. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020570

Lao D, Wang X, Chen T. Design and Error Calibration of a Machine Vision-Based Laser 2D Tracking System. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):570. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020570

Chicago/Turabian StyleLao, Dabao, Xiaojian Wang, and Tianqi Chen. 2026. "Design and Error Calibration of a Machine Vision-Based Laser 2D Tracking System" Sensors 26, no. 2: 570. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020570

APA StyleLao, D., Wang, X., & Chen, T. (2026). Design and Error Calibration of a Machine Vision-Based Laser 2D Tracking System. Sensors, 26(2), 570. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020570