Ground Maneuvering Target Detection and Motion Parameter Estimation Method Based on RFRT-SLVD in Airborne Radar Sensor System †

Highlights

- This paper presents a high-order phase compensation and parameter estimation algorithm designed for maneuvering targets, which effectively balances detection performance and computational efficiency.

- The proposed method achieves precise compensation of high-order range migrations without the need for exhaustive parameter search, thereby circumventing the blind speed sidelobe effect. Futhermore, the incorporation of a time-delay variable significantly improves the anti-noise capability of the approach.

- This algorithm introduces a novel motion compensation technique to address the challenges of range migration, Doppler frequency migration, and Doppler ambiguity in detecting weak maneuvering targets. It achieves precise range migration compensation with enhanced accuracy and robustness, forming a vital preprocessing step for high-quality SAR imaging.

- The algorithm supports simultaneous multi-target processing and holds promising application potential in fields such as airborne radar detection, maritime moving target indication, cooperative observation by UAV formations, and other fields.

Abstract

1. Introduction

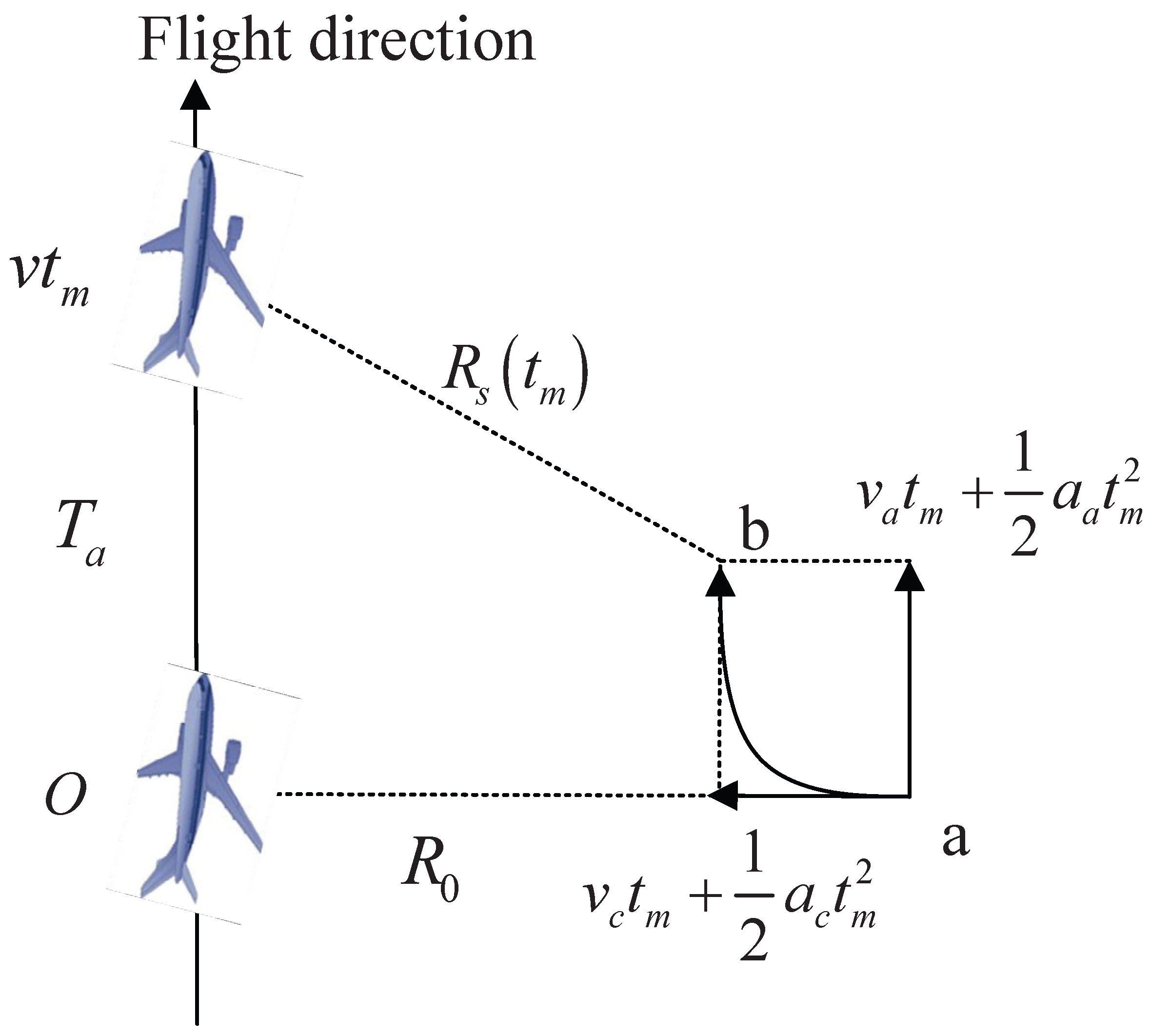

2. Signal Model

3. Proposed Coherent Integration Algorithm

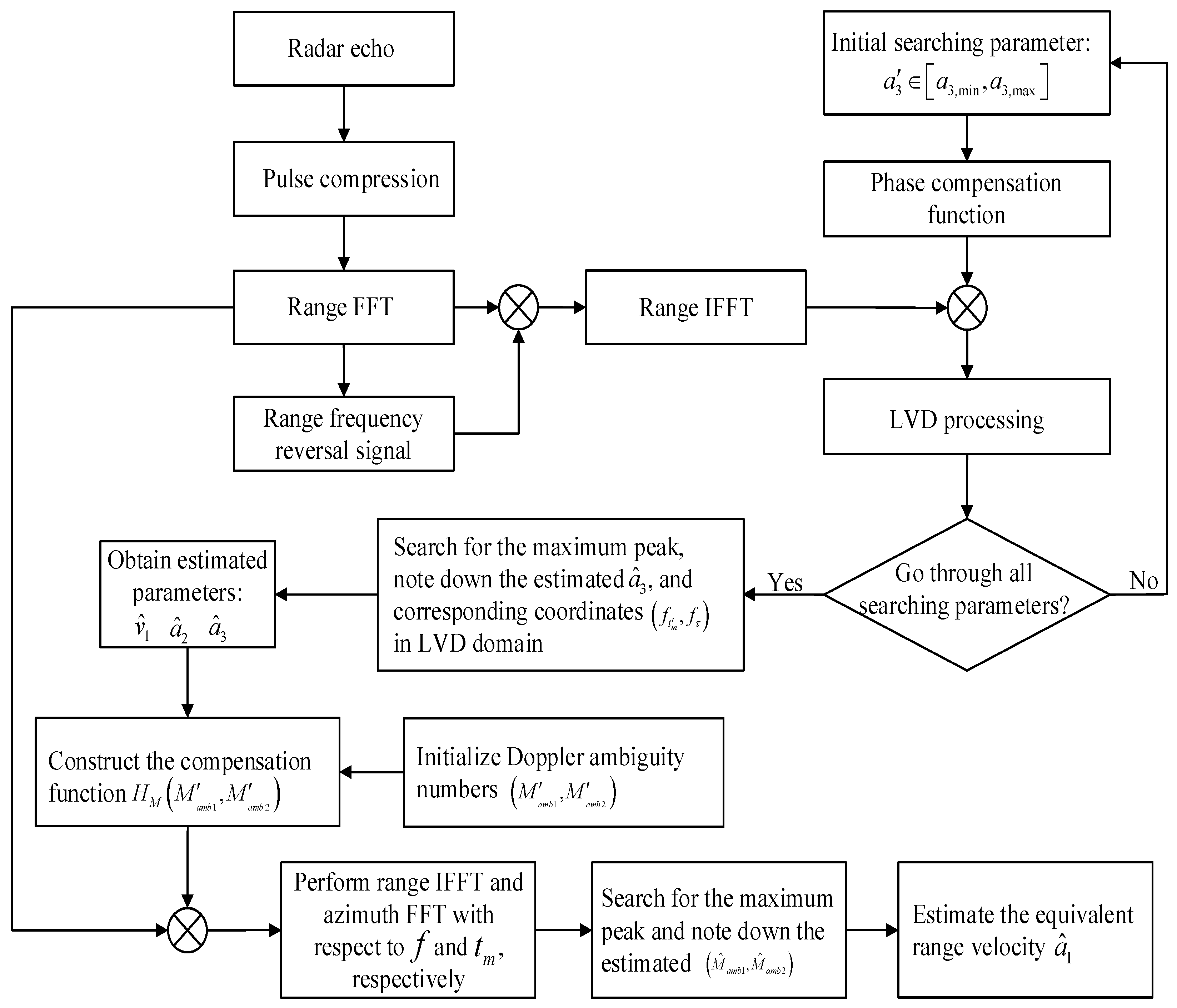

3.1. RM Compensation by RFRT

3.2. QDFM Correction by PCF

3.3. Coherent Integration via LVD

3.4. Parameter Estimations of the Proposed Method

4. Performance Analyses of the Proposed Method

4.1. Coherent Integration for Multiple Targets

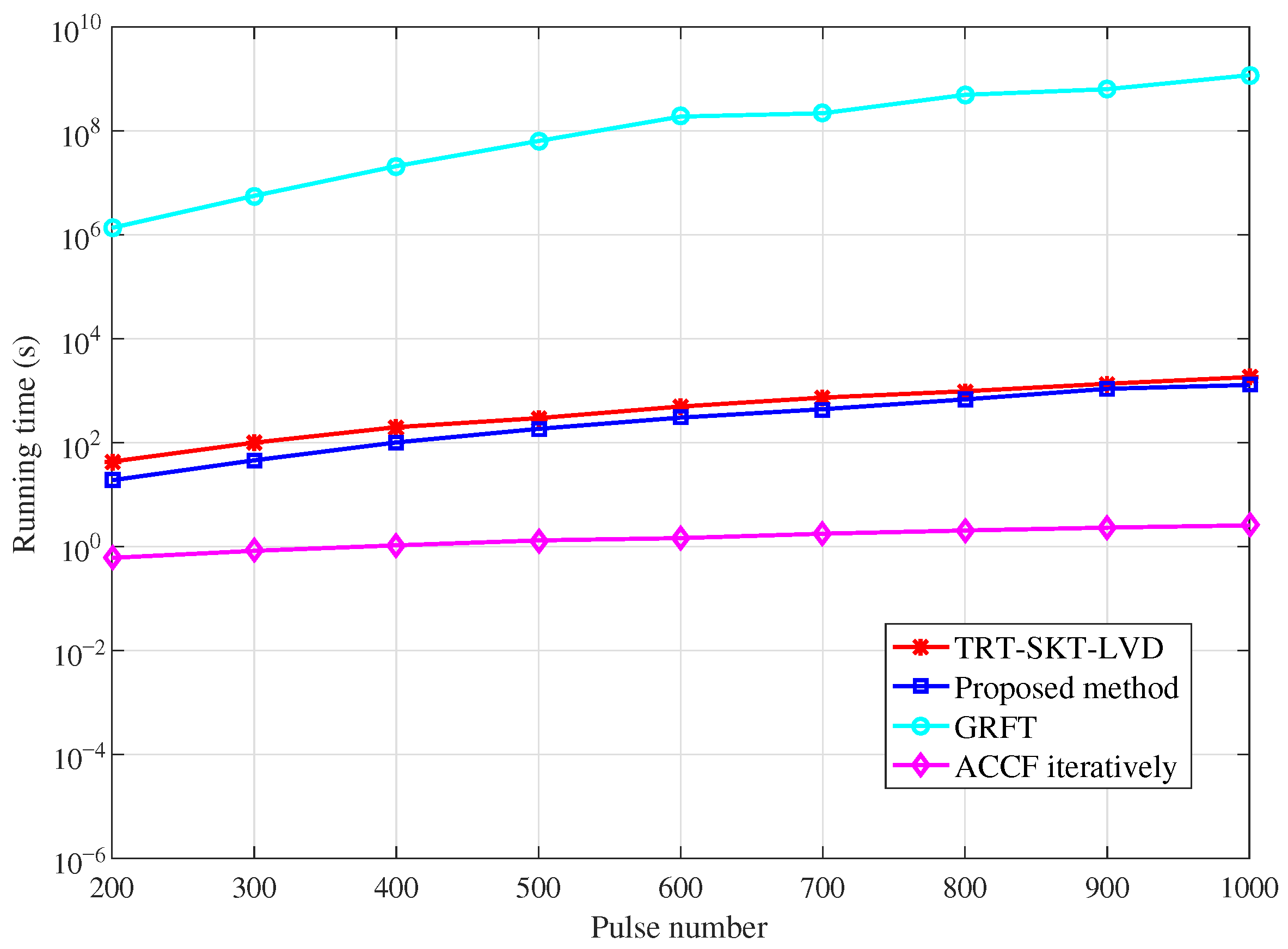

4.2. Comparisons of Computational Complexity

5. Results and Discussion

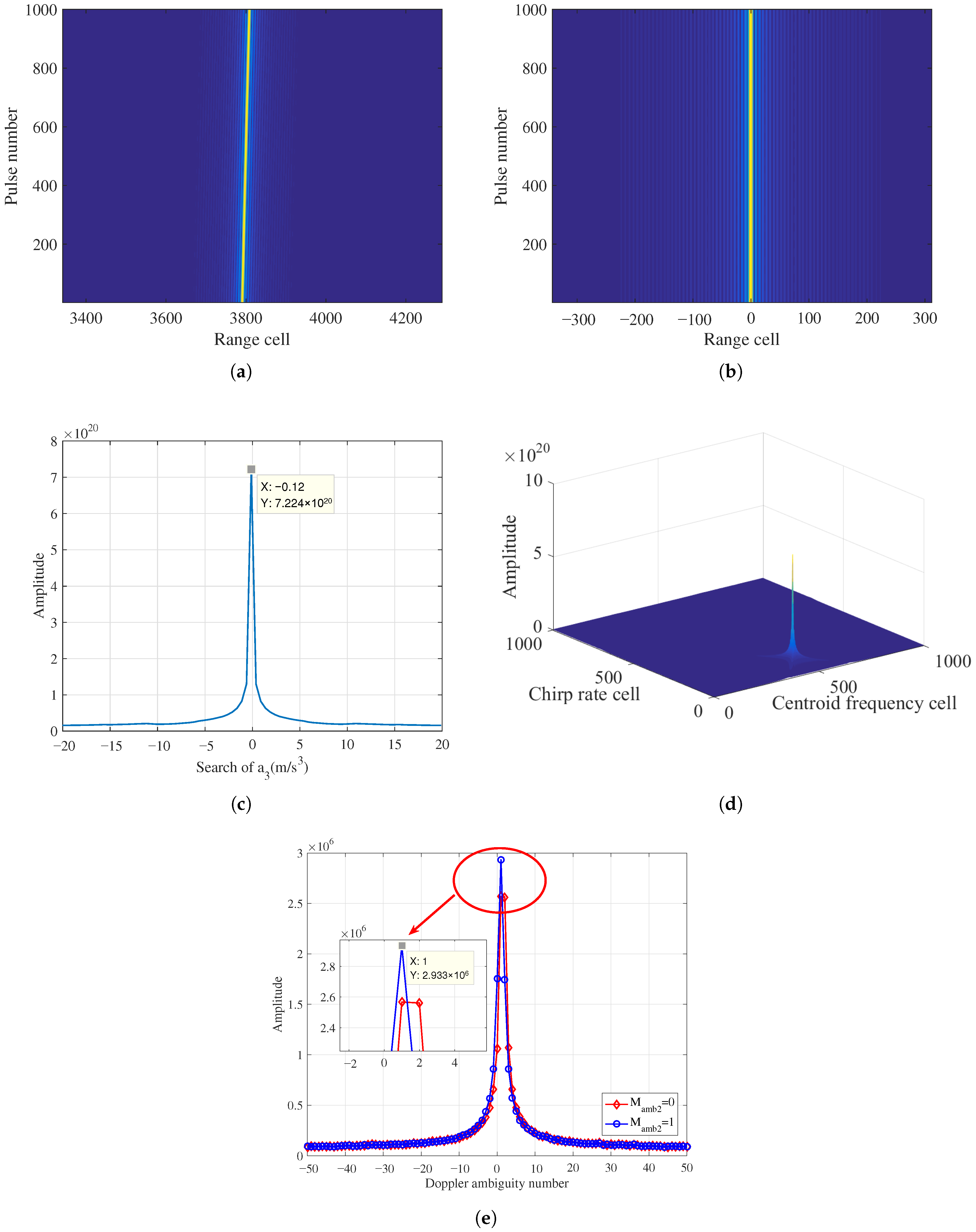

5.1. Coherent Integration for Single Target

5.2. Analyses of Multiple Targets

5.3. Parameter Estimation Performance

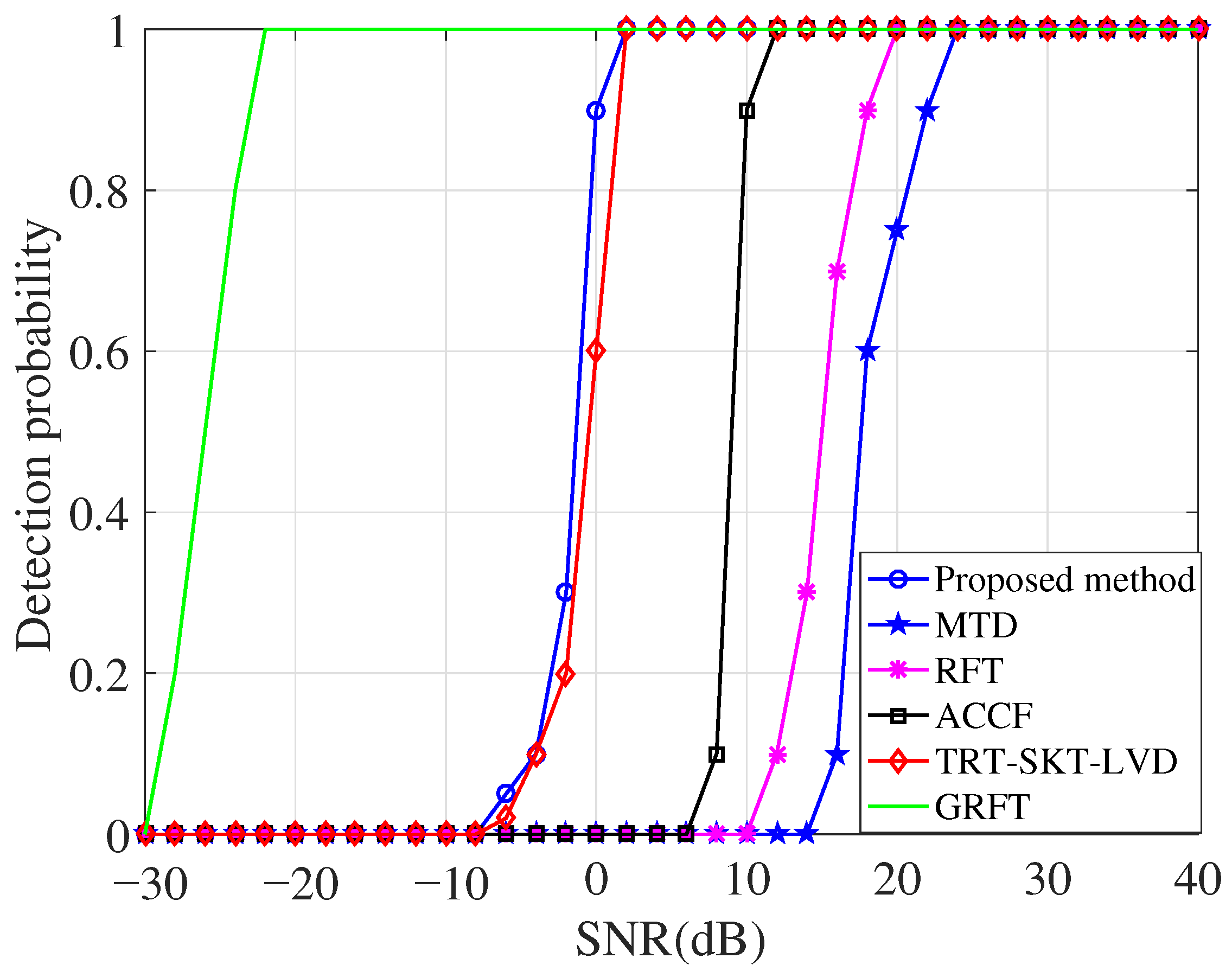

5.4. Analyses of Detection Ability

6. Conclusions

- The proposed technique achieves precise RM compensation while avoiding the BSSL effect;

- It reduces the parameter search space from high dimensions to one dimension, and thus has a relatively low computational complexity;

- Through the introduction of a 1-D lag-time variable, the LVD operation improves the signal accumulation gain and enhances the noise robustness;

- The proposed approach demonstrates effective suppression of cross-term interference and enables simultaneous detection of multiple targets.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, X.; Pan, Z.; Zhou, H. Cross-Attention Transformer for Coherent Detection in Radar Under Low-SNR Conditions. Sensors 2025, 25, 7588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Li, D.; Luo, X.; Song, D.; Liu, H.; Su, J. Ground Maneuvering Targets Imaging for Synthetic Aperture Radar Based on Second-Order Keystone Transform and High-Order Motion Parameter Estimation. IEEE J. Sel. Topics Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 2019, 12, 4486–4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandra, R.; Sahai, A. SNR walls for signal detection. IEEE J. Sel. Topics Signal Process. 2008, 2, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Lu, X.; Su, W.; Gu, H.; Yang, J. Efficient Long-Time Coherent Integration and Detection Algorithm for Radar High-Speed Target Based on the Azimuth Resampling Technology. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2024, 60, 1091–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Cao, D.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Y. Detection of Ground Maneuvering Target Based on Range Frequency Reversal Transform and Searching Lv’s Distribution. In Proceedings of the 2023 8th International Conference on Communication, Image and Signal Processing (CCISP), Chengdu, China, 17–19 November 2023; pp. 416–420. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, P.; Xia, X.-G.; Liao, G.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Liu, X. Ground Moving Target Refocusing in SAR Imagery Using Scaled GHAF. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 56, 1030–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, Q. Weak and Maneuvering Target Detection with Long Observation Time Based on Segment Fusion for Narrowband Radar. Sensors 2022, 22, 7086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Min, R.; Cao, Z.; Pi, Y. High-order RM and DFM correction method for long-time coherent integration of highly maneuvering target. Signal Process. 2019, 162, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, R.; DiPierto, R.; Fante, R. SAR imaging of moving targets. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 1999, 35, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Z. A keystone transform without interpolation for SAR ground moving-target imaging. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2007, 4, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yu, J.; Peng, Y.; Xia, X.-G. Radon-Fourier Transform for Radar Target Detection, I: Generalized Doppler Filter Bank. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2011, 47, 1186–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yu, J.; Peng, Y.; Xia, X.-G. Radon-Fourier transform for radar target detection (II): Blind speed sidelobe suppression. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2011, 47, 2473–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, X.; Tao, H.; Su, J.; Guo, X.; Zhang, J. Axis rotation MTD algorithm for weak target detection. Digit. Signal Process. 2014, 26, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Su, T.; Zhu, W.; He, X.; Liu, Q. Radar high-speed target detection based on the scaled inverse fourier transform. IEEE J. Sel. Topics Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 2015, 8, 1108–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Li, X.; Yi, W.; Cui, G.; Kong, L. A Coherent detection and velocity estimation algorithm for the high-speed target based on the modified location rotation transform. IEEE J. Sel. Topics Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 2018, 11, 2346–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Guan, J.; Liu, N.; He, Y. Maneuvering target detection via Radon-Fractional Fourier transform-based long-time coherent integration. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2014, 62, 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Guan, J.; Liu, N.; Zhou, W.; He, Y. Detection of a low observable sea-surface target with micromotion via the Radon-linear canonical transform. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2014, 11, 1225–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Liao, L.; Yang, Z.; Xia, X.-G.; Ma, J.; Zhang, X. An approach for refocusing of ground moving target without target motion parameter estimation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zhang, J.; Xu, S.; Liu, H.; Liu, Q. Radar Detection and Motion Parameters Estimation of Maneuvering Target Based on the Extended Keystone Transform. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 76060–76074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Xing, M.; Xia, X.-G.; Wu, Y.; Bao, Z. Robust Ground Moving-Target Imaging Using Deramp–Keystone Processing. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2013, 51, 966–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, X.; Tao, H.; Xie, J.; Su, J.; Li, W. Long-time coherent integration detection of weak manoeuvring target via integration algorithm improved axis rotation discrete chirp-Fourier transform. IET Radar Sonar Navig. 2015, 9, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Kong, L.; Cui, G.; Yi, W. A low complexity coherent integration method for maneuvering target detection. Digit. Signal Process. 2016, 49, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cui, G.; Kong, L.; Yi, W.; Yang, X.; Wu, J. High speed maneuvering target detection based on joint keystone transform and CP function. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Radar Conference, Cincinnati, OH, USA, 19–23 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Xia, X.-G.; Peng, S.; Yu, J.; Peng, Y.; Qian, L. Radar maneuvering target motion estimation based on Generalized Radon-Fourier transform. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2012, 60, 6190–6201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Li, X.; Cui, G.; Yi, W.; Yang, Y. Coherent Integration Algorithm for a Maneuvering Target with High-Order Range Migration. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2015, 63, 4474–4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Liao, G.; Yang, Z.; Xia, X.-G.; Ma, J.-T.; Ma, J. Long-time coherent integration for weak maneuvering target detection and high-order motion parameter estimation based on keystone transform. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2016, 64, 4013–4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wei, X.; Yang, D.; Wang, H.; Li, X. ISAR Imaging of Targets With Complex Motion Based on Discrete Chirp Fourier Transform for Cubic Chirps. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2012, 50, 4201–4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’shea, P.P. A fast algorithm for estimating the parameters of a quadratic FM signal. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2004, 52, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farquharson, M.M.; O’shea, P.P. Extending the performance of the cubic phase function algorithm. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2007, 55, 4767–4774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cui, G.; Kong, L.; Yi, W. Fast non-searching method for maneuvering target detection and motion parameters estimation. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2016, 64, 2232–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cui, G.; Yi, W.; Kong, L. Fast coherent integration for maneuvering target with high-order range migration via TRT-SKT-LVD. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2016, 52, 2803–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Liao, G.; Yang, Z.; Xia, X.-G.; Ma, J.; Zheng, J. Ground Maneuvering Target Imaging and High-Order Motion Parameter Estimation Based on Second-Order Keystone and Generalized Hough-HAF Transform. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 320–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Bi, G.; Wan, C.; Xing, M. Lv’s Distribution: Principle, Implementation, Properties, and Performance. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2011, 59, 3576–3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiurewicz, J.; Kulpa, K.; Czekala, Z.; Filipek, T.A. Radar detection of helicopters with application of CLEAN method. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2012, 48, 3525–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Prozzi, J.; Hong, F. Quantification of Post-Rainfall Moisture Content in Pavement Unbound Layers Using Long-Term Pavement Performance Data. Transp. Res. Rec. 2025; early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Q.; Li, J.; Sacchi, M.D.; Zhuang, M.; Liu, Q. Simultaneous prediction of petrophysical properties and formation layered thickness from acoustic logging data using a modular cascading residual neural network (MCARNN) with physical constraints. J. Appl. Geophys. 2024, 224, 105362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Methods | Computational Complexity | Search Dimension |

|---|---|---|

| RFRT-SLVD | 1-D search | |

| TRT-SKT-LVD | 2-D search | |

| GRFT | 4-D search | |

| ACCF iteratively | without search |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Carrier frequency | 5 GHz |

| Bandwidth | 10 MHz |

| Pulse duration | 50 μs |

| Pulse repetition frequency | 1 kHz |

| Sample frequency | 60 MHz |

| Accumulation time | 1 s |

| Nearest slant range | 2 km |

| Flight velocity of radar | 120 m/s |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Along-track velocity | |

| Cross-track velocity | |

| Along-track acceleration | |

| Cross-track acceleration |

| Parameter | Target 1 | Target 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Nearest slant range () | 2 | 1.2 |

| Along-track velocity () | 10 | 10 |

| Cross-track velocity () | −45 | 48 |

| Along-track acceleration () | 5 | −7 |

| Cross-track acceleration () | 1 | 3 |

| SNR after PC () | 12 | 12 |

| Parameters | Velocity (m/s) | Acceleration (m/s2) | Jerk (m/s3) | Doppler Ambiguity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| True Value | Estimated Value | True Value | Estimated Value | True Value | Estimated Value | |||

| Target 1 | 45 | 44.9962 | 3.5333 | 3.5323 | −0.3043 | −0.3 | 1 | 1 |

| Target 2 | −48 | −48.0068 | 3.5417 | 3.5398 | 0.5225 | 0.5 | −2 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lin, L.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Cao, D.; Wang, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, X. Ground Maneuvering Target Detection and Motion Parameter Estimation Method Based on RFRT-SLVD in Airborne Radar Sensor System. Sensors 2026, 26, 559. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020559

Lin L, Zhao Y, Yang Y, Cao D, Wang H, Liu L, Chen X. Ground Maneuvering Target Detection and Motion Parameter Estimation Method Based on RFRT-SLVD in Airborne Radar Sensor System. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):559. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020559

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Lanjin, Yang Zhao, Yang Yang, Dong Cao, Haibo Wang, Linyan Liu, and Xing Chen. 2026. "Ground Maneuvering Target Detection and Motion Parameter Estimation Method Based on RFRT-SLVD in Airborne Radar Sensor System" Sensors 26, no. 2: 559. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020559

APA StyleLin, L., Zhao, Y., Yang, Y., Cao, D., Wang, H., Liu, L., & Chen, X. (2026). Ground Maneuvering Target Detection and Motion Parameter Estimation Method Based on RFRT-SLVD in Airborne Radar Sensor System. Sensors, 26(2), 559. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020559